Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 14

The Psychological Meaning of Self-Forgiveness in a Collectivist Context and the Measure Development

Authors Hsu HP

Received 2 September 2021

Accepted for publication 26 November 2021

Published 16 December 2021 Volume 2021:14 Pages 2059—2069

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S336900

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Hsin-Ping Hsu

Department of Psychology, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan

Correspondence: Hsin-Ping Hsu

Department of Psychology, National Cheng Kung University, No. 1, University Road, Tainan, 701, Taiwan

Tel +886-6-2757575#56510

Email [email protected]

Purpose: Self-forgiveness requires a cognitive reframing of one’s views of the self. It may be a positive situational strength, and it has been shown that higher levels of self-forgiveness are related to well-being and a specific personality type. However, the concept, per se, and the inner healing process of self-forgiveness are still unclear because of a lack of cultural awareness in this research field. The current research aimed to conduct a conceptual analysis in a collectivist context and create an optional measurement scale for assessing self-forgiveness in a target population.

Methods and Results: In Study 1, using multidimensional scaling (MDS), the findings suggested that the conceptual structure of self-forgiveness among Taiwanese participants (N = 232) can be categorized into three dimensions: embodied awareness, positive change, and wisdom growth. The scale was created by using item analysis, factor analysis, hierarchical regression analysis, and correlation analyses in Study 2 (N = 231) and Study 3 (N = 805), the scale was found to have adequate reliability and validity, and the scores correlated with measures of self-control and resilience.

Conclusion: The constructs of self-forgiveness among a sample in Taiwan have three basic psychological meanings. The measure designed here is supported by adequate psychometric evidence. Further research will be necessary to increase the understanding of self-forgiveness cross-culturally, provide additional empirical validation and methodological refinement within different target groups, and investigate intra-individual positive strength change for the improvement and practical application of the current measurement tool.

Keywords: cultural mind, resilience, positive psychology, self-control, self-forgiveness, well-being

Introduction

Over the past decade, the amount of research and understanding of self-forgiveness has grown exponentially. It appears that self-forgiveness, along with several other mental health correlates in different societies, has a strong predictive power for psychological well-being.1–3 Research has shown that higher levels of self-forgiveness are related to biopsychosocial well-being, and more significantly, serve as a shield against several disorders, such as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder.4–8 For example, it appears that individuals with constant exposure to stressful situations, such as care workers, are at an increased risk of burnout, compassion fatigue, and secondary traumatic stress.9,10 As a result, it is clear that self-forgiveness may be an important personality strength, particularly when the subject receives negative feedback after putting effort into their work or applies self-judgment after making a mistake.11,12 Furthermore, self-forgiveness requires a cognitive reframing of one’s views of the self, which takes place after an individual has entered the process of introspection.13 However, the concept per se and the healing process of self-forgiveness are still relatively unclear.

Self-Forgiveness in Collectivist Contexts

Self-forgiveness has shown to have a strong predictive power for well-being in many different cultural contexts. However, cross-cultural research comparing individuals from East Asian and Western countries across several parameters, such as reasoning, social judgment, and emotional styles, has shed light on the emerging differences that may underlie each culture’s perception-related, cognitive, and emotional hierarchies.14–16 Some of the important cultural factors needed to reach a more in-depth understanding of the phenomenon include the differences in cultural value systems, the existence or absence of a particular philosophical system, and the economics of a given country.17 For example, considering the differences between cultures, Western cultures, in general, are characterized by individualism, which promotes values such as self-confidence, achievement, and independence; whereas Eastern cultures are predominantly characterized by collectivism, which stresses the importance of obedience, social rules, and interdependence.18,19 In Taiwan, there is a prevalence of collectivism, with roots in Confucianism.20,21 Based on this belief system, one’s complete dedication to life responsibilities and self-sacrifice are highly praised and regarded as high moral attainments. Not only do these factors affect individuals in Taiwan, but the ideals of face preservation and forbearance also play key roles in everyday life. Therefore, it can be inferred that achieving a state of self-forgiveness after committing a mistake, especially when something is important, may not be easy. People still share similar stressful situations worldwide, but culture plays a pivotal role in understanding the same psychological concept. Consequently, it has been speculated that culture may have a distinct effect on how a mistake is experienced among people in collectivist contexts; self-sacrifice and refraining from mistakes while maintaining unconditional empathy for specific persons are expected, mainly because according to the tenets of Confucianism, pain and suffering are to be kept to oneself and endured.22 Furthermore, differences among Western and East Asian emotional styles have been noted. Compared to members of Western countries, members of East Asian countries on average tend to employ more dialectical emotions that are characterized by the “middle way” or a “dialectical emotional style” rather than the emotional extremes of their Western counterparts.14,23 Hence, based on Confucianism, the structure of the concept of self- forgiveness would contain not only a hedonic tendency, but also an un-hedonic mental state, which may reflect an aspect of the complexity of self-forgiveness not found in Western societies. In addition, it has long been too “WEIRD” (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) in psychology researches.24 Therefore, a better understanding of self-forgiveness from different cultural contexts will provide a valuable reference for the development of an appropriate measurement tool, cross-cultural comparisons, and theory construction for future studies. The trend towards globalization and establishing value on the findings from non-Western countries in positive psychology can truly make this field authentically positive.25

The Current Status of Self-Forgiveness Measurement

In the past, multiple measurements of self-forgiveness have been developed. Mauger et al developed the Forgiveness of Self Subscale (FOSS),26 which is one of the dimensions measured on the Forgiveness Scale. Thompson et al27 developed the Heartland Forgiveness Scale (HFS), with one subscale designed to assess self-forgiveness. A scenario-based measurement, the Multidimensional Forgiveness Scale (MFS), was developed by Tangney, Boone, Fee and Reinsmith;28 this scale is composed of eight different scenarios and participants answer according to the likelihood of forgiving themselves in potential situations. As Strelan29 indicates, self-forgiveness is multi-faceted and of a complex nature. However, the FOSS and HFS are dispositional approaches and focus on reducing self-condemnation, which is only one particular facet of self-forgiveness, whereas the MFS has no clear theoretical basis when scoring. All three measures have limitations. The State Self-Forgiveness Scale (SSFS; Wohl et al8) consists of two subscales with a total of 17 items to assess the feelings, actions, and beliefs toward self-forgiveness when making a mistake. The SSFS has been the most used measure since its creation and the items use a situational approach, which may apply to societies that value contextual premises. However, this measure lacks a conceptualization procedure as the basis for compiling the items. Thus, the present research sought to develop an optional measure that includes a conceptual analysis process that can increase the bandwidth of the assessment of self- forgiveness but also ameliorate the acquiescence of cultural bias in existing measures derived from Western perspectives.

The Relationships Among Self-Forgiveness, Self-Control, and Resilience

As external criteria of the current measurement development, variables that can indicate a person’s capacity to change and adjust to pursue compatibility between the self and the world were chosen for assessment: self-control and resilience. Previous studies have identified that self-control and resilience can regulate negative emotions.30,31 Furthermore, self-control is a good indicator of self-regulation, and predicts a person’s resilience.32 Identifying influential factors that promote resilience is an essential task in the field of psychology and behavioral management. Hence, as self- forgiveness is also a type of self-regulation, we may expect that by adding self-forgiveness as a predictor for resilience, there will be benefits in the explanation of the existing variance. Moreover, although a person with high self-control may feel upset when making a mistake, they tend to treat negative situations as chances to grow, which can encourage (or force) the self to place a greater focus on achieving goals, and they will subsequently “bounce back” from frustrations in the long run. Thus, self-forgiveness, self-control, and resilience can be treated as human strengths in positive psychology and share similar effectiveness on self-healing through the maintenance of a growth mindset. Accordingly, self-control can positively predict resilience, whereas self-forgiveness may enhance the relationship between self-control and resilience. In addition, self-control is a highly praised virtue in Eastern cultures, representing a person’s hardy personality when facing stressful situations33,34 and the cultivation of self to avoid indulgences or depravities. Thus, self-control and resilience were selected as external criteria for validity measurements.

Present Study

With the rapid growth in self-forgiveness research, it is important to reflect on the problem regarding the lack of conceptual analysis of self-forgiveness, and the scarcity of measures derived from the samples from collectivistic societies. Hence, the psychological meaning of self-forgiveness was examined among Taiwanese participants to enhance conceptualization and further develop an optional measure called the Self-Forgiveness Scale (SFS) containing cultural-related features and testable psychometric properties. Accordingly, three studies were conducted to construct the theoretical concepts of self-forgiveness (Study 1), generate the items (Study 2), examine reliability and validity, and explore the association between the SFS, self-control, and resilience (Study 3).

Study 1: Theoretical Construction of the Dimensionality of Self-Forgiveness

Methods

Participants and Procedure

The purpose of Study 1 was to examine the psychological constructs of self-forgiveness. Participants were instructed to complete an online free association task. They were presented with the term “self-forgiveness” and asked to provide as many answers as possible when thinking about it. Next, the word association analysis paradigm was adopted to select the most important and frequently used response words, after which, collaborative analysts were invited to categorize these words along with the researcher. The collaborative analysts yielded from various professional backgrounds (one clinical psychologist, one social psychologist, one associate professor, one assistant professor, two Ph.D. candidates with excellent data analysis skills, and three employees with bachelor’s degrees). They ranged from 28 to 46 years of age. The study was implemented in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the National Cheng Kung University Governance Framework for Human Research Ethics in Taiwan, and all participants provided informed consent.

The words were integrated into common themes after a consensus was reached among all analysts. Afterward, the researcher designed a pairwise pairing concept rating scale based on the elements, and the collaborative analysts helped rate the similarity between each pair of phrases. Subsequently, the obtained data were entered into the statistical software and analyzed by adopting non-metric multidimensional scaling (MDS). By using perceptual maps, complex data can be extracted and represented by spatial dimensions. Study 1 employed a community sample of 232 Taiwanese adults (186 females), aged 21–62 years (M = 32.82, SD = 8.57). The average working experience was seven years (SD = 6.58). Altogether, 57% had a religious affiliation, 39% had no religious affiliation, and for 4%, the religious affiliation was unknown.

Materials

Word-Association Task. The design and procedure of this task were adapted from the word association paradigm. Participants were presented with the term “self-forgiveness” in Chinese (ziwokuanshu) to elicit specific perceptions associated with the term in question. Participants were instructed to respond using any words, sentences, or thoughts that came to their mind using the online form, containing 15 blank spaces, following the order in which those words, sentences, or thoughts appeared in their minds. This task required the order of words to be written as they were thought, ie, the first thought was to be written in the first blank, second in the second blank, etc. The rationale behind such a strategy is that the thoughts written out first are more strongly associated with the given term and dominate those written in subsequent blanks. Participants were encouraged to start forming free associations and writing as many answers as possible to the stimulus word until no more ideas came to their minds. The original data gathered a total of 737 response items. On average, each person provided 3.18 items. After merging the repeated responses and deleting the apparently meaningless words that were beyond the scope of the instructions given to participants, the set was reduced to 360 independent response words. Subsequently, the responses that only appeared once and had the lowest score after weighting were omitted, and hence the final set included 77 associated words employed in deep structure analysis. Self-Forgiveness Concept Rating Scale. Through discussions with co-analysts and by integrating the response words, the emerging categories were classified and sorted into the following six themes: “transformation”, “tolerance”, “action”, “enhancement”, “confrontation”, and “religion”. Based on these six elements (Table 1), a pairwise match was designed, resulting in a total of fifteen pairs. By utilizing a 5-point Likert scale, the rating scale was developed. The co-analysts were instructed to do the similarity assessment for each pair of concepts and assign it a point value ranging from 1 to 5. The lower scores revealed that the concepts in the given pair were closely related having a similar meaning, whereas the higher scores signified the emergence of distinct meanings among the concepts.

|

Table 1 Classifications and Definition of the Associated Words for Self-Forgiveness |

Results

Through the analysis of the word association paradigm, 77 response words were identified regarding self-forgiveness. They were classified into six categories: “transformation” (35 items), “tolerance” (13 items), “action” (12 items), “enhancement” (6 items), “confrontation” (6 items), and “religion” (5 items). The judgment based on the elements derived from the psychological meaning of self-forgiveness in the population of adults. Further, the MDS results indicated that a three- dimensional solution provided the most concise representation of the data and the proper related values (stress = 0.15, RSQ = 51%) for interpreting the results of Study 1.

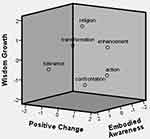

As displayed in Table 2 and Figure 1, the numbers of each vector represented the stimulus coordinates used for grouping. Accordingly, “enhancement” and “action” can be grouped and named “positive change”; “transformation” and “religion” can collectively be named “wisdom growth”; and “tolerance” and “confrontation” can be integrated into “embodied awareness”. To be more precise, “positive change” was defined here as the change that occurs through externalizing and positive behaviors; “wisdom growth” as growth through the realization of one’s inner peace and spiritual transformation; and “embodied awareness” as learning through the awareness of one’s own non- hedonic mind-body experiences, which may stir some negative feelings or thoughts. Therefore, three essential psychological constructs of self-forgiveness among the Taiwanese population were identified in Study 1.

|

Table 2 The Stimulus Coordinates of Three Spatial Dimensions of Self-Forgiveness |

|

Figure 1 The three spatial vectors of self-forgiveness. |

Study 2: Item Generation, Item Analysis, and Verification of the Factor Structure

Methods

Participants and Procedure

The purpose of Study 2 was to develop a brief and optional measure, the Self-Forgiveness Scale (SFS), for people living in collectivist contexts. The first step was to generate and evaluate the question items and verify the three components found in study 1. Related literature was also reviewed and the initial question item pool was generated based on the concepts derived from the three aspects. Then, the items were revised and modified by consulting one clinical psychologist and two social psychologists. After that, fifteen items were developed to assess the quality through item analysis. The participants (N = 231) were recruited from local communities. The average age was 46.93 years (SD = 14.87), among which 134 were females (58%), and 23 participants (10%) did not provide this demographic characteristic. Participants completed the question items online, rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The study was implemented in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the National Cheng Kung University Governance Framework for Human Research Ethics in Taiwan, and all participants provided informed consent.

Results

Item Analysis

Comparisons of extreme groups and corrected item-total correlations were utilized to check for discrimination and homogeneity. The t-tests for the discrimination index of the three aspects of the original 15 items were statistically significant, all ps <0.001. However, two items were deleted from subsequent data analysis; one because of a higher measure of internal consistency after deletion and another for its low correlation coefficient (ie, r = 0.19). Thus, 13 items were retained to verify the factor structure found in Study 1 through factor analysis.

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Internal Consistency

The principal axis factoring (PAF) was conducted by following a direct oblimin method for oblique rotation. For the first round of EFA, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin index (KMO) was 0.85 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant, χ2 (78) = 1373.51, p < 0.001. The results of Study 1 guided a three-factor structure extraction. The analysis showed that one item was not kept in its original component, so it was removed. Twelve items remained for the second run of EFA. The Kaiser-MeyerOlkin index (KMO) was 0.83, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant, χ2 (66) = 1217.97, p < 0.001. The analysis indicated that each factor contained the expected initial items, and the factor loadings ranged from 0.39 to 0.86. Hence, a three-factor structure extraction was confirmed, and the factor solution explained 52.78% of the variance. The internal consistency was measured to evaluate the reliability with Cronbach’s alpha for the 12-item SFS (α = 0.86) and each sub-factor: embodied awareness (α = 0.77), positive change (α = 0.85), and wisdom growth (α = 0.72). Table 3 goes here. Self-Forgiveness Scale item pool.

|

Table 3 Self-Forgiveness Scale Item Pool |

Study 3: Replication of the Factor Structure, Validity Investigation, Association with Other Variables, and Test-Retest Reliability

Methods

Participants and Procedure

There were three phases in Study 3. In Phase 1, the aim was to replicate the three-factor structure and measure the validity of the SFS. A sample of 276 participants (55.8% female) was selected for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The participants’ average age was 21.54 years (SD = 4.44). In Phase 2, additional community participants were recruited to measure the validity and explore the association between the SFS and other psychological measures. A total of 429 participants (58% female) took part in phase 2. The participants’ average age was 31.82 years (SD = 15.1). In Phase 3, the aim was to offer evidence for the temporal stability of the SFS and to assess the test-retest reliability for scores on two-week interval measures. A sample of 100 new participants, among which 66 were female, completed the scale twice. The participants’ average age was 21.0 years (SD = 1.01). The study was implemented in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the National Cheng Kung University Governance Framework for Human Research Ethics in Taiwan, and all participants provided informed consent.

Materials

Self-Forgiveness Scale (SFS). The author designed this measurement to assess self-forgiveness among Taiwanese adults. It contains twelve items on a 5-point Likert scale with endpoints 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. The scale is composed of three domains: embodied awareness (α = 0.72), positive change (α = 0.70), and wisdom growth (α = 0.66). The total Cronbach’s alpha was 0.77. Higher total scores reflect greater levels of self-forgiveness (Table 3). State Self-Forgiveness Scale (SSFS; Wohl et al).8 Since the SSFS has been the dominant measure and the items are of a situational orientation, the SSFS was selected as the indicator of convergence validity for the study. The state of self-forgiveness was assessed with 17 items and composed of two subscales, self-forgiving feelings and actions (α = 0.64) and self-forgiving beliefs (α = 0.84). Participants were instructed to complete each item on a 5-point rating scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (completely). The total Cronbach’s alpha was 0.86. Higher scores reflect greater levels of self-forgiveness, and nine items were reverse scored. Brief Resilience Scale (BRS; Smith et al).35 Resilience was selected as an external criterion for validity measurement. The BRS was used to evaluate the ability to bounce back or recover from adversity. It contains a unitary construct with six items responded on a 5-point scale with endpoints 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.77. Higher scores reflect greater levels of resilience, and three items were reverse scored. Brief Self-Control Scale (BSCS; Tangney et al).36 Self-control was also selected as an external criterion for validity measurement. The BSCS, a 13-item measure, was used to assess self-control. Items were scored on 5-point scales (1 = strongly agree, 5 = strongly disagree). The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.68. Higher scores reflect greater levels of self-control, and there were seven items reverse scored.

Results

Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Construct Validity

In phase 1, the researcher performed CFAs on the 12-item SFS with Amos 23.0 to test whether the three-factor solution fit the data and to confirm the final selection of the items. Maximum likelihood estimates were used, and the model was modified based on the modification indices (MI). Finally, the three-factor CFA with correlated residuals (constrained to be equal) between e3 and e4 as well as e9 and e12 (Figure 2) revealed an acceptable fit based on the standards of past literature;37,38 the χ2/df = 2.69, goodness of fit index (GFI) = 0.92, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.92, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.078, 90% confidence interval (CI) of RMSEA [0.062, 0.095] suggesting items tapped three latent factors. The final set of SFS items is presented in Table 3. The researcher conducted the subsequent analyses in phase 2 using this 12-item scale. Figure 2 goes here. Confirmatory factor analysis of the modified model of self-forgiveness scale and the three first-order factors (N = 276).

Associations Between the SFS and Other Variables

In phase 2, to test the convergent and criterion validity of the SFS, a bivariate correlational analysis with the SSFS, the SCS, and the BRS was conducted (see Table 4). As expected, the SFS was correlated with the SSFS, r (403) = 0.23, p < 0.001, which supports the convergent validity because these two measures were designed to assess a similar mental concept. The SCS, r (414) = 0.20, p < 0.001, and BRS, r (417) = 0.19, p < 0.001, were also associated with the SFS, which supports the concurrent validity. Furthermore, a hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to assess the incremental validity39,40 of the SFS based on how well it predicted the intensity of resilience with self-control (see Table 5). In the analysis, Model 1 had self-control as a predictor, and Model 2 included self- forgiveness as an additional predictor. By comparing Model 2 against Model 1, the result indicated that self-forgiveness explained an additional 1.6% (ΔR2 = 0.016, ΔF2 (1, 411) = 7.87, p = 0.005) of the variance of resilience beyond what was already explained by the trait of self-control.

|

Table 4 Descriptive Data and Correlations Between the SFS and Other Psychological Measures |

|

Table 5 Results of Hierarchical Regression Analysis of the Two Predictive Models of Resilience (n = 429) |

Test-Retest Reliability

In phase 3, the Pearson correlation coefficient of the first test was positively associated with that at the time of the second test (r = 0.72, p < 0.001). The scores of all three factors on the first test were positively associated with their corresponding scores on the second test: embodied awareness (r = 0.57, p < 0.001), positive change (r = 0.73, p < 0.001), and wisdom growth (r = 0.66, p < 0.001). The findings indicated that the stability of the scale is good over time.

General Discussion

Existing measures regarding self-forgiveness from Western societies only focus on the construct of self-regard and have lacked a process of conceptualization coming from an analysis of the perspectives of the target groups when generating the items. As noted earlier, the structure of the concept of self-forgiveness was predicted to contain a hedonic tendency and an un-hedonic mental state in Eastern societies based on the tenets of Confucianism. In addition, self-forgiveness could be understood by being treated as a situational strength rather than a disposition. Therefore, because the sample comprised members of a collectivist society, the researcher expected that perceived un- hedonic self-cultivation could be one aspect of the constructs regarding self-forgiveness among Taiwanese participants. Furthermore, when coming face to face with feelings of remorse or self- condemnation, self-forgiveness does not represent an instant change of mindset; instead, it seems that the healing process takes time and must incorporate at least some degree of pain and negative feelings in order for the actor to take responsibility, which is a key point if one is to benefit from and increase the process of genuine self-forgiveness.41 That is, “well-being is not the absence of distress”,42 and there is no quick fix when it comes to convalescing. Accordingly, the construct of self-forgiveness found in the study exhibited a factor called “embodied awareness,” which contained two un-hedonic elements: “tolerance” and “confrontation”. It signifies learning through the awareness of one’s un-hedonic mind-body experiences, which may spawn certain negative feelings or thoughts. Despite such elements, this component of self- forgiveness could still be of great importance and may reflect the evidence put forth by some previous studies, namely that self-forgiveness can sometimes be heart-rending and uncomfortable.43 It also represents that people in collectivist contexts are frequently requested to make self-sacrifices and refrain from mistakes through experiencing pain and suffering,22 which reflects an essential aspect of self-forgiveness not found in Western studies. In addition, self-forgiveness can be treated as “positive change” and “wisdom growth”; the former is the process of changing through externalizing and positive behaviors, and the latter involves the process of growing through the realization of one’s inner peace and spiritual transformation. These two factors imply that the hedonic element (via self-compassion) and religious beliefs (via divine forgiveness) regulate emotion, which was also suggested by related literature.42,43 In this study, three essential psychological constructs of self-forgiveness were identified among the Taiwanese population. Based on these three aspects, the initial item pool of the measurement tool consisted of 15 items representing the attributes of self-forgiveness in a collectivist context, but three items were subsequently eliminated based on the EFA results. The three-factor CFA with correlated residuals revealed an acceptable fit and the final 12-item SFS was established. The results showed adequate test-retest reliability and provided support for the preliminary psychometric investigation. Self-forgiveness is an important character and a healing strategy for people taken to diminish the difficulties in emotion regulation.12,44 It has been defined as “a willingness to abandon self- resentment in the face of one’s own acknowledged wrong, while fostering compassion, generosity, and love toward oneself”.45 Apparently, self-forgiveness is closely related to the factors which can indicate a person’s capacity to change and adjust to pursue compatibility between the self and the world. Previous studies have identified that self-control and resilience can regulate negative emotions.30,31 Thus, they were selected as external criteria for validity measurements. In the current study, the findings indicated that self-forgiveness is related to self-control and resilience, which support the convergent and concurrent validity. Consistent with the findings of past studies, greater self-forgiveness correlates with specific traits and higher emotion regulation ability.7,46 In addition, as self-forgiveness is also a type of self-regulation, the result indicated that self-forgiveness explained an additional variance of resilience beyond what was already explained by self-control. This study has several limitations. First, the researcher invited academic experts and community participants to score in Study 1. Due to different training and living backgrounds, the experts may have had different mindsets when scoring. If different weighting scores were given to distinct groups of raters, the bias may have been reduced and the classifications made more stable in the long run. Second, the results indicated that self-control and resilience were positively correlated with self- forgiveness with a small effect size (|r| < 0.30), which might be due to the larger sample size, self- report bias, or the common method variance. For example, the current SFS was designed with no reverse-scored items, and the criterion variables were all assessed with the same 5-point Likert scale. In addition, self-control and resilience were high with inherent features, while self-forgiveness is more suitable for being a situational strength because of its complex conceptual characteristics. As such, self-control and resilience were positively correlated with self-forgiveness with a small effect size. With regards to the quality and enhancement of SFS, further development could use various data collecting methods, continue to enlarge the item pool, and verify the construct based on greater theoretical clarity.

Conclusions

People from non-Western societies may have different mentalities on the concept of self- forgiveness. Hence, the current research aims to explore and define the psychological meaning of self-forgiveness via construct analysis in a collectivist context. The results do not only provide a standard protocol for future researchers to develop a measurement to assess the subjective experience of self-forgiveness in different cultural societies, but also expand the literature of the concept of self- forgiveness with a different standpoint. In addition, the current study indicated not only the reflections on the related past research, but further added the indispensable cultural perspective. All things considered, the preliminary findings of the current study indicate that the construct of self-forgiveness among a sample in Taiwan has three basic psychological meanings: positive change, wisdom growth, and embodied awareness. The designed measure is with adequate psychometric evidences, and it can be an optional measurement for assessing self-forgiveness in collectivist contexts. The results highlight the value of self-forgiveness–related research for understanding individual differences in non-Western cultural societies. Further research is suggested to augment the understanding of this area through cross-culture studies and scenario design, as well as to provide additional empirical validation and methodological refinement within different target groups or investigate intra-individual positive strength change for the improvement and practical application of the current measurement.

Acknowledgment

The author wishes to thank Anastazija Popesku, Makeba Dudley, and Tzu-Shan Lin for their assistances at the initial stage of the study. This research was supported by a grant from the Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology, 107-2410-H-006-001.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Bugay A. Measuring the differences in Pairs’ marital forgiveness scores: construct validity and links with relationship satisfaction. Psychol Rep. 2014;114(2):479–490. doi:10.2466/21.02.PR0.114k18w5

2. Davis D, Ho M, Griffin B, et al. Forgiving the self and physical and mental health correlates: a meta-analytic review. J Couns Psychol. 2015;62(2):329–335. doi:10.1037/cou0000063

3. McConnell J. A conceptual-theoretical-empirical framework for self-forgiveness: implications for research and practice. Basic Appl Soc Psychol. 2015;37(3):143–164. doi:10.1080/01973533.2015.1016160

4. Bryan A, Theriault J, Bryan C. Self-forgiveness, posttraumatic stress, and suicide attempts among military personnel and veterans. Traumatol. 2015;21(1):40–46. doi:10.1037/trm0000017

5. Fisher M, Exline J. Self-forgiveness versus excusing: the roles of remorse, effort, and acceptance of responsibility. Self Identity. 2006;5(2):127–146. doi:10.1080/15298860600586123

6. Krause N, Hayward R. Self-forgiveness and mortality in late life. Soc Indic Res. 2012;111(1):361–373. doi:10.1007/s11205-012-0010-3

7. Maltby J, Macaskill A, Day L. Failure to forgive self and others: a replication and extension of the relationship between forgiveness, personality, social desirability and general health. Pers Individ Dif. 2001;30(5):881–885. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00080-5

8. Wohl M, DeShea L, Wahkinney R. Looking within: measuring state self-forgiveness and its relationship to psychological well-being. Can J Behav Sci. 2008;40(1):1–10. doi:10.1037/0008-400x.40.1.1.1

9. Figley CR. Compassion fatigue: coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized. Brunner/Mazel; 1995.

10. Slocum-Gori S, Hemsworth D, Chan W, Carson A, Kazanjian A. Understanding compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue and burnout: a survey of the hospice palliative care workforce. Palliat Med. 2013;27(2):172–178. doi:10.1177/0269216311431311

11. Cornish M, Wade NA. Therapeutic model of self-forgiveness with intervention strategies for counselors. J Couns Dev. 2015;93(1):96–104. doi:10.1002/j.15566676.2015.00185.x

12. Macaskill A. Differentiating dispositional self-forgiveness from other-forgiveness: associations with mental health and life satisfaction. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2012;31(1):28–50. doi:10.1521/jscp.2012.31.1.28

13. Ingersoll-Dayton B, Krause N. Self-forgiveness: a component of mental health in later life. Res Aging. 2005;27(3):267–289. doi:10.1177/0164027504274122

14. Miyamoto Y, Ryff C. Cultural differences in the dialectical and non-dialectical emotional styles and their implications for health. Cogn Emot. 2011;25(1):22–39. doi:10.1080/02699931003612114

15. Peng K, Nisbett R. Culture, dialectics, and reasoning about contradiction. Am Psychol. 1999;54(9):741–754. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.54.9.741

16. Peng K, Spencer-Rodgers J, Nian Z. Naïve dialecticism and the Tao of Chinese thought. In: Kim U, Yang KS, Hwang KK, editors. Indigenous and Cultural Psychology: Understanding People in Context. Boston, MA: Springer; 2006:247–262. doi:10.1007/0-387-28662-4_11

17. Liu C, Spector P, Shi L. Cross-national job stress: a quantitative and qualitative study. J Organ Behav. 2007;28(2):209–239. doi:10.1002/job.435

18. Hofstede G. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1980. doi:10.1177/017084068300400409

19. Triandis HC. Generic individualism and collectivism. In: The Blackwell Handbook of Cross-Cultural Management. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2017:16–45. doi:10.1002/9781405164030.ch2

20. Wang S, Tamis-Lemonda C. Do child-rearing values in Taiwan and the United States reflect cultural values of collectivism and individualism? J Cross Cult Psychol. 2003;34(6):629–642. doi:10.1177/0022022103255498

21. Zhang Y, Lin M, Nonaka A, Beom K. Harmony, hierarchy and conservatism: a cross-cultural comparison of Confucian values in China, Korea, Japan, and Taiwan. Commun Res Rep. 2005;22(2):107–115. doi:10.1080/00036810500130539

22. Yau S, Xiao X, Lee L, Tsang A, Wong S, Wong K. Job stress among nurses in China. Appl Nurs Res. 2012;25(1):60–64. doi:10.1016/j.apnr.2011.07.001

23. Spencer-Rodgers J, Peng K, Wang L, Hou Y. Dialectical self-esteem and East-West differences in psychological well-being. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2004;30(11):1416–1432. doi:10.1177/0146167204264243

24. Henrich J, Heine S, Norenzayan A. Most people are not WEIRD. Nature. 2010;466(7302):29. doi:10.1038/466029a

25. Hendriks T, Warren M, Schotanus-Dijkstra M, et al. How WEIRD are positive psychology interventions? A bibliometric analysis of randomized controlled trials on the science of well-being. J Posit Psychol. 2018;14(4):489–501. doi:10.1080/17439760.2018.1484941

26. Mauger PA, Perry JE, Freeman T, Grove DC, McBride AG, McKinney KE. The measurement of forgiveness: preliminary research. JPC. 1992;11:170–180.

27. Thompson LY, Snyder CR, Hoffman L. Heartland Forgiveness Scale. [Faculty Publications]. Lincoln, NE, US: Department of Psychology, University of Nebraska-Lincoln; 2005:452.

28. Tangney JP, Boone AL, Fee R, Reinsmith C. Multidimensional Forgiveness Scale. Fairfax, VA: George Mason University; 1999.

29. Strelan P. The measurement of dispositional self-forgiveness. In: Woodyatt L, Worthington EL, Wenzel JM, Griffin BJ editors. Handbook of the Psychology of Self-Forgiveness. Springer International Publishing AG; 2017:75–86. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-60573-9_6

30. Rothbaum F, Weisz J, Snyder S. Changing the world and changing the self: a two-process model of perceived control. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1982;42(1):5–37. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.42.1.5

31. Ungar M. Resilience across cultures. Br J Soc Work. 2008;38(2):218–235. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcl343

32. Hofmann W, Luhmann M, Fisher R, Vohs K, Baumeister R. Yes, but are they happy? Effects of trait self-control on affective well-being and life satisfaction. J Pers. 2013;82(4):265–277. doi:10.1111/jopy.12050

33. Kobasa S, Maddi S, Kahn S. Hardiness and health: a prospective study. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1982;42(1):168–177. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.42.1.168

34. Maddi S. Hardiness: the courage to grow from stresses. J Posit Psychol. 2006;1(3):160–168. doi:10.1080/17439760600619609

35. Smith B, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Christopher P, Bernard J. The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. Int J Behav Med. 2008;15(3):194–200. doi:10.1080/10705500802222972

36. Tangney JP, Baumeister RF, Boone AL. High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. J Pers. 2004;72:271–324. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00263.x

37. Hooper D, Coughlan J, Mullen MR. Structural equation modeling: guidelines for determining model fit. EJBRM. 2008;6:53–56. doi:10.21427/D7CF7R

38. Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling.

39. Haynes S, Lench H. Incremental validity of new clinical assessment measures. Psychol Assess. 2003;15(4):456–466. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.15.4.456

40. Sechrest L. Incremental validity: a recommendation. Educ Psychol Meas. 1963;23(1):153–158. doi:10.1177/001316446302300113

41. Peterson S, Van Tongeren D, Womack S, Hook J, Davis D, Griffin B. The benefits of self-forgiveness on mental health: evidence from correlational and experimental research. J Posit Psychol. 2016;12(2):159–168. doi:10.1080/17439760.2016.1163407

42. Fincham F, May R. Self-forgiveness and well-being: does divine forgiveness matter? J Posit Psychol. 2019;14(6):854–859. doi:10.1080/17439760.2019.1579361

43. Woodyatt L, Wenzel M, Ferber M. Two pathways to self‐forgiveness: a hedonic path via self‐compassion and a eudaimonic path via the reaffirmation of violated values. Br J Soc Psychol. 2017;56(3):515–536. doi:10.1111/bjso.12194

44. Hall J, Fincham F. The temporal course of self–forgiveness. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2008;27(2):174–202. doi:10.1521/jscp.2008.27.2.174

45. Enright RD. Counseling within the forgiveness triad: on forgiving, receiving forgiveness, and self-forgiveness. Couns Values. 1996;40(2):107–126. doi:10.1002/j.2161-007X.1996.tb00844.x

46. Hodgson L, Wertheim E. Does good emotion management aid forgiving? Multiple dimensions of empathy, emotion management and forgiveness of self and others. J Soc Pers Relat. 2007;24(6):931–949. doi:10.1177/0265407507084191

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.