Back to Journals » Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation » Volume 7

The National Acupuncture Detoxification Association protocol, auricular acupuncture to support patients with substance abuse and behavioral health disorders: current perspectives

Received 19 July 2016

Accepted for publication 19 October 2016

Published 7 December 2016 Volume 2016:7 Pages 169—180

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/SAR.S99161

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Li-Tzy Wu

Video abstract presented by Dr Elizabeth B Stuyt.

Views: 5659

Elizabeth B Stuyt,1 Claudia A Voyles2

1Department of Psychiatry, University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Pueblo, CO, 2Department of Clinical Studies, AOMA Graduate School of Integrative Medicine, Austin, TX, USA

Abstract: The National Acupuncture Detoxification Association (NADA)-standardized 3- to 5-point ear acupuncture protocol, born of a community-minded response to turbulent times not unlike today, has evolved into the most widely implemented acupuncture-assisted protocol, not only for substance abuse, but also for broad behavioral health applications. This evolution happened despite inconsistent research support. This review highlights the history of the protocol and the research that followed its development. Promising, early randomized-controlled trials were followed by a mixed field of positive and negative studies that may serve as a whole to prove that NADA, despite its apparent simplicity, is neither a reductive nor an independent treatment, and the need to refine the research approaches. Particularly focusing on the last decade and its array of trials that elucidate aspects of NADA application and effects, the authors recommend that, going forward, research continues to explore the comparison of the NADA protocol added to accepted treatments to those treatments alone, recognizing that it is not a stand-alone procedure but a psychosocial intervention that affects the whole person and can augment outcomes from other treatment modalities.

Keywords: National Acupuncture Detoxification Association (NADA), ear acupuncture, acudetox, addiction, mental health, trauma

Introduction

Auricular acupuncture has been used extensively in substance abuse treatment programs, hospitals, and prisons throughout the USA and the world for the past 30 years despite limited research evidence of its effectiveness. Several reviews of randomized placebo-controlled trials (RCTs) of acupuncture in addiction treatment have been done with conflicting results. In 2004, Alberto conducted a review of six RCTs of the use of the National Acupuncture Detoxification Association (NADA) protocol in the treatment of cocaine/crack abuse.1 Although all the six were found to have a good quality of methodology, they had conflicting outcomes and Alberto concluded that this review could not provide a definite answer as to the efficacy of auricular acupuncture in the treatment of cocaine/crack abuse. In 2012, Lua and Talib published a review of eight RCTs using 3–5 standardized NADA points in the treatment of drug addiction with emphasis on the length of treatment course, needle-points, outcome measures, reported side effects, and overall outcomes.2 They included four of the same studies reviewed by Alberto, two of which both reviews found to demonstrate positive outcomes,3,4 and two both agreed had negative outcomes.5,6 Alberto included two other studies considered to have negative outcomes,7,8 and Lua and Talib included four other studies, two of which they concluded had positive outcomes9,10 and two had negative outcomes.11,12 Lua and Talib concluded that based on their review, the overall effectiveness of auricular acupuncture in treating drug addiction remains inconclusive. However, they added that the NADA protocol seemed to hold some potential as an additional component of substance abuse management due to its lack of adverse effects, simple administration, and acceptability to patients.2

In 2013, White published a review of 48 RCTs of acupuncture for drug dependence on alcohol, cocaine, nicotine, and opioids in which he included studies using auricular points, body points, and either manual or electrical stimulation.13 Comparing these studies is difficult in that there are so many variables including body points, ear points, standardized and individualized point selection, bilateral, unilateral, manual stimulation and electrical stimulation of the points, and a wide range of different controls and different outcome measures. White concluded that half of the trials he reviewed had at least one positive result, lending support to the concept that acupuncture has some benefits in treating drug dependence; however, the evidence is inconsistent due to the large number of variables in treatment and outcomes. He suggests that trials of the NADA protocol should be done with truly inactive controls, as looking at just the NADA protocol trials, he found that 80% of the studies with non-needle controls were positive versus 33% that used sham, possibly active, controls. White also posits that looking only at abstinence, attrition, craving, and withdrawal may miss other significant responses to acupuncture.

It is clear from these reviews that research on the NADA protocol is difficult to perform for several reasons. It is difficult to apply the gold standard Western approach of “randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials” because, although it is possible to randomize subjects, it is very difficult to blind the recipient and is impossible to blind the therapist. There is also significant evidence that sham acupuncture, often used as the placebo, is not inert.14 Furthermore, the NADA protocol is also not just the insertion of five ear needles. The NADA protocol is a style of engaging in which the environment and intention of the practitioner play significant roles in the outcome of the treatment. NADA treatments are usually done in a group setting, creating an environment that is reassuring and validating. NADA practitioners sit with patients as supportive witnesses. Patients learn they can sit quietly. The NADA protocol is a nonverbal patient-centered intervention that facilitates participation in individual and group treatment sessions. It is not a stand-alone intervention. As Wan pointed out in an elegant letter to the editor in 2016, complementary and alternative medical treatment “differs from conventional medicine in that therapy is often tailored to the individual patient. This personalized, holistic approach is fundamentally at odds with the constraints of the randomized controlled trial (RCT).”15 He advocates instead for pragmatic trials that look at the overall effect of one treatment compared with another, comparing clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

This review focuses solely on research and literature published about the NADA-standardized 3- to 5-point ear acupuncture protocol as this is used by most treatment programs. It is a protocol that can be utilized by many different disciplines depending on local laws. It is a cost-effective intervention with minimal side effects that facilitates other aspects of treatment, and it lends itself to research because it is a standardized protocol. This review covers the historical developmental roots of NADA, how practice and research on the protocol have evolved over time, and recommendations for the future. The specific aims are to chronologically review the studies that have been published on acupuncture for addiction that were included in previous review articles and evaluate the literature specific to the NADA protocol from the last 5 years which include other areas of behavioral health often related to addiction recovery.

Materials and methods

This is not a systematic review. The authors searched PubMed, EBSCOE (which includes MEDLINE), Google Scholar, and Research Gate, scanning the reference section of found articles for additional citations. The keywords used for this search are: “NADA,” “National Acupuncture Detoxification Association,” and “acudetox,” all without quotation marks, with no restrictions on populations studied or type of trial. Inclusion criteria included full text in English studies published in peer-reviewed journals from 2011 to 2016. Only studies of the NADA protocol, also known as acudetox, using the ear acupuncture combination of up to 5 points, Shen Men, Sympathetic, Kidney, Liver, and Lung (without electric stimulation), are included.

History of the NADA protocol

Although the use of acupuncture to treat various medical conditions has been around for thousands of years, the use of acupuncture in the treatment of addiction is a relatively recent phenomenon. A mid-twentieth-century French neurologist, Nogier created a systemized map correlating the ear to the rest of the body.16 This makes it theoretically possible for practitioners to stimulate ear points and effect change in the area of the body which is represented on the ear.

Hsiang-Lai Wen, a neurosurgeon in Hong Kong, discovered, serendipitously in 1972, that needles inserted in the ear – intended as a preoperative anesthetic – abated physical withdrawal symptoms from opium. Intrigued, Wen decided to try to replicate this effect, and in 1973, Wen and Cheung published their findings in treating 40 heroin- and opium-addicted individuals with electro-potentiated ear and body acupuncture in the Asian Journal of Medicine.17 The New York Times article on these findings included this quote from Wen, “We don’t claim it’s a cure for drug addiction. If we can treat the withdrawal symptoms, make the patient more comfortable, and alleviate their suffering, then we have achieved something. Our treatment is not the complete answer to drug addiction.”18

The NADA-standardized 3- to 5-point ear acupuncture protocol treatment for drug and alcohol abuse was primarily developed at Lincoln Hospital, in the impoverished South Bronx, New York. Galvanized by the lack of services for their community, activists, including members of the Young Lords and Black Panthers, radical Puerto Rican and African American organizations were instrumental in creating the initial Lincoln Detox program, a methadone-assisted detoxification for heroin addicts, one of the first of its kind.18

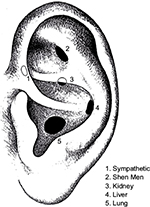

Wanting more natural, nonpharmaceutical interventions, Lincoln adopted Wen’s method17 using electrical stimulation of the lung point in the ear.19 The ear acupuncture protocol was expanded by trial and error over several years, under the leadership of Michael Smith, MD, DAc, with the ultimate resultant combination: “Shen Men,” “Sympathetic” (sometimes noted in the literature as “Autonomic”), “Kidney,” “Liver,” and “Lung”5 (Figure 1).20 What also developed was the understanding of the ear treatment not just as relieving acute withdrawal but offering a long-term, preventative, or “tonification” effect.21 Over the ensuing years, Lincoln dropped methadone and electric stimulation and developed a client-centered style of treatment useful for alcohol and other drugs of abuse.

| Figure 1 NADA protocol points-Sympathetic, Shen Men, Kidney, Liver, and Lung. Abbreviation: NADA, National Acupuncture Detoxification Association. |

In 1985, NADA was founded and incorporated by Smith and others in order to promote the training of behavioral health clinicians. The term “acudetox” was adopted to differentiate it from other forms of acupuncture, indicating that this is a standardized protocol, not requiring the practitioner to make a diagnosis and determine treatment points. The synonymous terms “acudetox” and “the NADA protocol” refer to the integrated style of treatment as well as the insertion of standardized acupuncture points in the outer ear. Lincoln functioned until 2011 as the largest training institute for Acupuncture Detoxification Specialists (ADS). NADA estimates that 25,000 have trained worldwide.22 However, the 2012 annual Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) national survey of programs found that 628 of the 14,311 tracked programs reported using acupuncture which means only a small number of clients receive this treatment.23

The NADA protocol is a very straightforward and low-cost tool that is not a stand-alone procedure, but aids in behavioral health treatment and recovery. Promotion of the use of this protocol has occurred primarily by word of mouth as opposed to well-funded pharmaceutical aids to treatment. Focusing on underserved communities and capacity-building remained core concepts as NADA spread.

The practice of acudetox has evolved to support substance abuse treatment and recovery, from harm reduction and pretreatment throughout the continuum of care to long-term recovery maintenance; to criminal justice applications from drug courts to jails and prisons; to all manner of substance and process addictions; to primary mental health and more recently chronic pain.20

During the early 2000s, acudetox took off around the world, beginning with the realization that the NADA protocol was helpful as a stress reduction technique, improving sleep and coping, not only in those with substance abuse problems but also in those exposed to horrific trauma.20 After the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center, an acudetox “stress reduction clinic” began in Manhattan providing >1,000 treatments in the first 10 days and continuing through 2007, funded by the Red Cross. NADA trainings were conducted in India and Thailand for Burmese refugee camps in 2001. The Pan-African Acupuncture Project brought NADA treatments to Uganda and surrounding regions in 2002. In 2003, the use of NADA in Substance Misuse Programs in the United Kingdom expanded to over 130 correctional facilities, and NADA-style treatments were developed in Peru, Mexico City, and the Philippines. In 2005, NADA members aided in Gulf Coast recovery efforts after hurricanes Katrina and Rita and in Kashmir following earthquakes, and the organization Acupuncturists Without Borders was developed using the NADA protocol in trauma and disaster relief settings around the world.24

One of the most common responses observed clinically from subjects receiving a NADA treatment includes reports of improved sleep and feeling calm enough to cope. This has been seen with the increasing episodes of trauma and disaster experienced worldwide. People involved in disasters such as wildfires or terrorist attacks are often too traumatized to even begin to talk about what they have experienced and often report difficulty sleeping. Many people in these situations have reported significant benefit from the NADA nonverbal treatment. This past year has seen the development of the Colorado Acupuncture Medical Reserve Corp (CAMRC).25 So far the only one of its kind in the USA, acupuncturists and ADS provide NADA treatments for victims of disasters as well as for first responders, including police, firefighters, hospital personnel, etc. The experience has been so positive that the recommendation is for other states to consider developing Medical Reserve Corp response which includes complementary treatments such as the NADA protocol. This constitutes a powerful example of “practice-based evidence.”

History of NADA research: early randomized-controlled studies

Some of the first research studies of the NADA protocol included a pilot study26 in 1987 followed by a placebo-RCT of severe recidivist alcoholics in 1989 in which 21 out of 40 subjects who received the NADA treatment points completed the treatment program, compared with one out of 40 in the control group who received nonspecific points, as sham.27 At 6 months follow-up, more subjects in the control group, compared with the treatment group, were found to have more than twice the number of drinking episodes and admissions to a detoxification center.

Washburn et al reported the first controlled investigation of the use of NADA in heroin detoxification in 1993 which randomly assigned 100 heroin-addicted adults to standard (NADA) treatment (n=55) or sham (geographically close points) (n=45) over a 21-day detoxification period.10 Although both the groups demonstrated an initial sharp drop in attendance, the sham treatment group showed a greater decline. Subjects receiving the NADA treatment attended the clinic more days than those in the sham group and were more likely to return for additional treatment beyond the 21-day detoxification period.

During the 1990s, there were several studies regarding the use of the NADA protocol for the treatment of cocaine addiction with mixed results. Some studies reported positive findings,3,28–30 whereas others reported no difference between the NADA protocol and the sham needle-insertion control group.5,7,31–33

In 1996, the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT) of the National Institutes of Health published Treatment Improvement Protocol Series 19 (TIP 19 “Detoxification from Alcohol and Other Drugs”), giving modest support for the use of acupuncture in opiate detoxification.34 This was followed in 1997 by the National Institutes of Health publishing Acupuncture. NIH Consensus Statement, which concluded, “There are other situations such as addiction, in which acupuncture may be useful as an adjunct treatment or an acceptable alternative or be included in a comprehensive management program.”35

A 1999 multivariant, retrospective cohort study of the 8,011 clients discharged from Boston publically funded detoxification programs found that only 18% of patients who received outpatient detoxification and counseling with the NADA protocol were readmitted to the system in 6 months as compared to 36% of those who had short-term residential detoxification without acudetox.36

In 2000, Avants et al published results of a well-designed study in which 82 cocaine-dependent, methadone-maintained patients were randomly assigned to receive the NADA protocol, a sham acupuncture control condition, or a non-needle relaxation control condition five times weekly for 8 weeks with three times weekly urine drug screen monitoring.4 Analysis of longitudinal urine toxicology data indicated that the NADA protocol was significantly more effective in reducing cocaine use than either a relaxation control (p=0.01) or a needle-insertion control (p<0.05).

This landmark study generated a significant amount of interest in NADA as a potential treatment and was followed by an attempt to replicate the findings in a larger, multisite trial of 620 patients in six sites throughout the USA.6 Although an intent-to-treat analysis of urine samples showed a significant overall reduction in cocaine use, the study found no differences between the three different treatment conditions. Although the authors admitted that counseling sessions in all three conditions were poorly attended, they concluded that their study did not support the use of acupuncture as a stand-alone treatment for cocaine addiction in situations in which patients receive only minimal, concurrent, psychosocial treatment. The authors did suggest that research needs to be done to examine the contribution of acupuncture to addiction treatment when provided in an ancillary role. However, as pointed out by White, 2002 marked a “watershed for both research into and use of acupuncture for drug dependence.”13 The use of acupuncture and research into its effects for substance abuse treatment fell off sharply, perhaps in response to this Journal of the American Medical Association study.

In a follow-up paper, Margolin et al carefully compared their original trial with their subsequent, consecutive portion of the large-scale replication study in an effort to understand and explain the disparity of outcomes with the same site and same population.9 The authors highlighted several significant shifts in the treatment design, notably the addition of cash incentives rewarding attendance (not abstinence) and the elimination of coping skills therapy groups.

Around the same time Bier et al published an excellent randomized, sham-controlled trial of the use of the NADA protocol in smoking cessation that demonstrated that acudetox is not a “stand-alone” treatment.37 When offered along with education and counseling, the NADA protocol was significantly more effective at reducing smoking than sham acupuncture with education and counseling, or than NADA acupuncture without clinical intervention. The combination of the NADA protocol and education and counseling resulted in a 40% reported smoking cessation compared with 22% cessation from sham acupuncture plus education and counseling and 10% cessation reported with the NADA protocol alone.

Expansion of NADA Research

Meanwhile NADA practice expanded with the anecdotal reports that the NADA protocol could provide benefit beyond supporting addiction recovery. Researchers followed suit also expanding the outcomes considered in behavioral health interventions.

In 2002, Berman and Lundberg published on a small pilot exploration of treating prison inmates in psychiatric units in Sweden with the NADA protocol.38 The authors found that several inmates experienced positive results and wanted to continue receiving treatment over several weeks. Those treated over 8 weeks reported experiencing improved inner harmony and calm and better clarity about future plans.

In 2004, Berman et al reported a RCT of the NADA protocol versus sham acupuncture on nonspecific helix points of male and female Swedish prison inmates with self-reported drug use.11 Participants were randomized to NADA (n=82) or sham (n=76) and offered 14 treatment sessions over 4 weeks. This study demonstrated that it is possible to use acudetox safely within a prison setting and that there was a demand for auricular acupuncture among prison inmates. Interestingly, the authors found drug use occurring in the NADA group (27% positive urines) but not in the sham group (0% positive urines). No significant adverse effects were observed in either group. Both the groups reported significant positive reduction over time in symptoms of physical and psychological discomfort. Patients’ reports of confidence in the NADA treatment increased over time while it decreased for the helix treatment. The absence of an untreated comparison group makes conclusions difficult but points to the need to conduct trials comparing NADA acudetox to inactive, non-sham controls.

In 2005, Janssen et al described the use of the NADA protocol to reduce substance use in the marginalized, transient population of Downtown Eastside Vancouver, British Columbia.39 NADA treatments were offered on a voluntary, drop-in basis 5 days per week. During a 3-month period, they generated 2,755 client visits and a reduction in the overall use of substances (p=0.01). Subjects reported a decrease in intensity of withdrawal symptoms, insomnia, and suicidal ideation (p<0.05). The authors concluded that NADA, in the context of a community-based harm reduction model, holds promise as an adjunct therapy for the reduction of substance use.

In 2005, Santasiero and Neussle examined the clinical and cost-effectiveness of the NADA protocol in an outpatient HMO chemical dependency program, comparing the outcomes for 22 patients who received at least 10 NADA sessions in addition to all the other components of the treatment program to 22 matched (sex/diagnoses) patients who had completed the same treatment program previously, but did not receive NADA treatments.40 At 6 months follow-up, the NADA-treated group had higher program completion rates (74% vs 44%), higher rates of negative urine drug screens (96% vs 85%), fewer inpatient rehabilitation days (39 vs 57 days), fewer inpatient psychiatric days (0 vs 3 days), and fewer outpatient detoxification episodes (0 vs 2) compared to the control group. They found significant cost saving in the NADA group compared with the control group and projected even greater cost saving over time.

In 2006, Stuyt and Meeker published results of a naturalistic study of 440 patients in a 90-day inpatient, tobacco-free, dual-diagnosis treatment program for substance abuse and mental illness.41 They compared patients who chose to receive the NADA protocol in a 5 days per week relaxation group compared to those who attended the same group but chose not to receive NADA needles. Length of stay in the program was significantly longer for those who participated in the NADA protocol. Patients who successfully completed the program participated in significantly more needling sessions and reported significant improvement in anger, concentration, sleep, energy, and pain management as compared with those who did not receive needles.

Although it is not practical or possible to randomize or control treatments in a disaster setting, in 2010 Yarberry reported on the benefits of the NADA protocol for Kenyan refugees experiencing symptoms of PTSD in a Ugandan camp in 2007.42

In 2006, CSAT updated TIP 19 with TIP 45 “Detoxification and Substance Abuse Treatment,” which contains several sections discussing the use of acupuncture, specifically NADA, in detoxification and substance abuse treatment.43 The TIP has given support to many people in the addiction treatment field to continue to use the NADA protocol, despite what many would say was lack of gold standard studies to confirm NADA as an evidence-based practice.44 Many NADA practitioners would counter with “what about Practice-Based Evidence?”

Current renewed interest in NADA research: 2011–2016

The current decade has seen renewed interest in the studies of the NADA protocol, most following a more pragmatic approach (Table 1). As Cowan pointed out in a 2011 review article, auricular acupuncture is used extensively in drug and alcohol treatment facilities, hospitals, and prisons in the UK, Europe, and the USA despite the lack of convincing research evidence.45 Practitioners of the NADA protocol laud it as a nonverbal, non-confrontational, effective, and well-received intervention; however, the lack of research evidence has resulted in lack of funding and therefore limited availability. Cowan also pointed out that because blinding is not possible, and sham acupuncture as placebo controls may have effects, RCTs should “assess effectiveness in conditions that reflect actual practice, which may include an ‘existing treatment’ control group and which concentrate on clinical significance, not just statistical significance.”45

In this vein, in 2011, Carter et al conducted a prospective trial in a self-selected population of 167 nonrandomized patients to evaluate the effectiveness of NADA in reducing the severity of seven common behavioral health symptoms associated with addictive substance use.46 They compared NADA-acupuncture-plus-conventional treatment versus conventional treatment alone within a highly structured 28-day residential treatment program. Sessions were offered twice weekly, and the patients were either in a “study hall” room (the control group) or a separate group NADA treatment room for 30-45 minutes. They found that patients reported the addition of NADA facilitated significant reduction in all symptoms measured including cravings, depression, anxiety, anger, body aches/headaches, poor concentration, and decreased energy compared with those who did not participate in the NADA treatments.

In 2011, Black et al attempted to study whether the NADA protocol helped reduce anxiety associated with psychoactive drug withdrawal in patients in an addiction treatment program.47 Subjects were randomized to either the NADA protocol (n=45) or sham acupuncture of five needles bilaterally in the helix (n=54) or relaxation control (n=41). All subjects were treated in the same room at the same time and were told that all three interventions were considered active treatments. All subjects received the usual standard of care for substance abuse. Subjects were instructed to attend three treatment sessions within a two week period. State anxiety levels, heart rate, and blood pressure were measured immediately before and after each treatment session. While only about a third of all subjects actually completed all three sessions, researchers found in these subjects there was a significant decrease in state anxiety scores and heart rate after treatment in all three groups but no difference in these decreases between the three treatment groups. It is unclear how Black et al47 could determine there was no difference between interventions when the interventions were very minimal (most receiving only one to two treatments), and these subjects were in usual substance abuse treatment for 2 weeks. Perhaps just being off the drugs for 2 weeks improved the outcome measures. However, there was no control for just treatment.

In 2012, Janssen et al published a trial of the NADA protocol in pregnant women who were using illicit drugs.48 Fifty women were randomized to receive NADA treatments and 39 to receive standard care. Although the study was limited by only 28% protocol compliance in the acupuncture arm, the women who participated in the NADA protocol were able to tolerate larger reductions in their methadone dose prior to delivery and their babies required almost two fewer days of morphine treatment. These infants were documented to have symptoms of neonatal withdrawal for shorter periods of time. This study supports the safety and feasibility of using NADA protocol to assist mothers to reduce their dose of methadone and mitigate the severity of neonatal abstinence syndrome.

Chang and Sommers reported in 2014 on a three-arm RCT with residents of a homeless veteran rehabilitation program.49 Sixty-seven participants were randomized to NADA treatments twice weekly for 10 weeks, relaxation response (RR) training once weekly as well as daily practice for 10 weeks, and usual care. They found that both active interventions significantly decreased cravings and anxiety levels, compared with usual care, and that there was continual improvement with additional intervention sessions over time for both NADA and RR. They concluded that “the availability of two effective non-pharmacological treatments-one relying on a provider (acupuncture) while the other is based on self-practice (the RR)-broadens treatment options for those who face a substance abuse problem.”

In 2014, Stuyt reported an outcome study of a tobacco-free 90-day inpatient dual-diagnosis treatment program in which the NADA protocol is available on a voluntary basis 4 days per week in addition to several other required evidence-based treatments as part of a comprehensive treatment program.50 The use of NADA acudetox was positively correlated with both successful completion of the program as well as successful tobacco cessation which ultimately improves the ability to maintain sobriety.51 What was most surprising in this study was the very significant correlation between the use of NADA in patients with borderline personality disorder and their successful completion of the program as well as their tobacco cessation and maintenance of sobriety a year after treatment.50 This is a population that historically does not do well in substance abuse treatment and are more likely to drop out of treatment prematurely.52 Since distress tolerance is a predictor of early treatment dropout,53 it is hypothesized that NADA acudetox helped with distress tolerance and allowed patients to begin to participate more effectively in other aspects of the treatment program.

In 2014, Bergdahl et al reported on a qualitative study describing patients’ experience of NADA treatment during protracted withdrawal.54 Fifteen patients reported their positive and negative experiences receiving NADA treatments twice weekly for 5 weeks. The respondents reported no major adverse effects following treatments. Minor negative experiences included brief transitory sensation of pain from the needles and the time-consuming nature of the treatment. Positive benefits clearly exceeded negative factors and included a reduction in protracted withdrawal symptoms and improved sleep quality. Participants also reported strong sensation of peacefulness, increased well-being, increased energy level, reduced physical discomfort, reduced irritability, and fewer alcohol and drug cravings.

In 2014, Reilly et al reported on the effectiveness of NADA acudetox as an intervention for the relief of stress and anxiety in health care workers experiencing burnout and compassion fatigue.55 Over 16 weeks, weekly NADA treatments were offered to all interested team members working in inpatient surgical burn/trauma intensive care and step-down units. Participants completed several survey tools before and after the completion of the intervention. Reilly et al55 found a significant reduction in reports of state anxiety as well as significant decreases in trait anxiety, burnout, and compassion fatigue compared with baseline reports.

In 2015, Carter and Olshan-Permutter reported on the benefits of NADA acudetox as a treatment for impulsivity, whether it is associated with substance use disorders or related to other concerns such as bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, attention deficit disorder, or intermittent explosive disorder.56 The authors argued that NADA, as a passive, nonverbal treatment, helps patients be “still” and experience stillness. Because it is effective immediately, acudetox may be more helpful in early stages of recovery when individuals may have a limited capacity to be still, focus, concentrate and learn techniques to help counter impulsivity such as Mindfulness-Based Therapies.

In 2016, De Lorent et al published a prospective parallel group clinical trial comparing the effectiveness of NADA with progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) in treating patients with anxiety disorder (AD) or major depressive disorder (MDD).57 They examined 162 patients who were actively enrolled in multimodal treatment including personal and group cognitive behavior therapy and psychopharmacological treatment for anxiety and/or depression. The participants in the study chose voluntarily between participating in NADA treatments or PMR treatment, both in a group setting. Each session lasted for 30 min and took place twice a week for 4 weeks. Shortly before and immediately after each treatment, each participant rated four items on a 0–100 mm visual analog scale (VAS) including tension, anxiety, anger/aggression, and mood. They found that for both the NADA treatment and the PMR treatment, VAS scores showed improvement in all items measured. There were no significant differences between the two treatments, and both showed significant effects in reducing anxiety, tension, and anger/aggression. They included a scale to measure patients’ regressive tendencies and found that this did not affect the treatment choice. They did not control for treatment as usual but opined that their results suggest that both NADA and PMR may be useful and equally effective additional interventions in the treatment of AD and MDD.

The most recently published RCT on the use of auricular acupuncture for substance use is an excellent example of the problems inherent in applying the RCT model to this treatment that is supposed to be holistic, patient-centered, and non-reductionist. Ahlberg et al attempted to devise a large, RCT that compared the NADA protocol for 15 sessions versus a local protocol “LP” which was essentially the same NADA protocol for 10 sessions versus a music listening relaxation control on self-report measures of anxiety, sleep, and substance use over a 3-month period.58 They reported finding that acupuncture was no more effective than relaxation for any of the studied measures. There were several flaws in their study design, and it was in reality not a true study of the NADA protocol in the fact that the acupuncture treatments were given individually and not in a group setting. All the patients in the study were actively participating in treatment as usual over the 3 months of the study, and there was no control group to evaluate this alone. The authors recruited 280 patients from a substance abuse clinic in Sweden and randomized them to the three different groups. They justified randomizing 120 to the relaxation control group versus 80 each to the two acupuncture groups because of their assumption that more people would drop out of the relaxation group because they were interested in getting acupuncture. This already speaks about the strength of the NADA protocol in retaining people in treatment reported by others; however, these authors did not address this as a possible flaw in their study. There was a significant dropout (57% by the third month) to the point that the authors did not reach the number of patients needed according to their initial power calculations; however, they published their results anyway. In the third month of their study, they had 37 out of 80 (46%) in the NADA group, 28 out of 80 (35%) in the LP group, and 36 out of 120 (30%) in the relaxation group remaining to be able to complete a self-report scale on anxiety. This alone appears to speak to the ability of acupuncture to help retain people in treatment but they did not address this. The fact that they conclude their article with the statement that they believe the results of their RCT raise questions about the clinical use of acupuncture in patients with substance use is very troubling.

In 2016, Bergdahl et al published a RCT of the NADA protocol compared with cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-i).59 Men and women who had been using a non-benzodiazepine hypnotic (z-drugs) at least three times a week for ≥6 months and still had insomnia were randomized to receive the NADA protocol (n=32) twice a week for 45 min for 4 weeks or CBT-i (n=35) 90-min sessions once a week for 6 weeks. It is unclear whether the subjects receiving the NADA protocol were treated individually or in a group setting but the treating acupuncturist left the room after inserting the needles; hence, this was not truly a NADA-style treatment. Both the treatments resulted in a clinically significant reduction in self-reported Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) scores at posttreatment and at 6-month follow-up. Not surprising, their main finding was that CBT-i was superior to the NADA protocol in decreasing insomnia symptoms and changing dysfunctional beliefs about sleep. They concluded that the NADA protocol would not be considered an effective stand-alone treatment for insomnia. It would have been interesting if they had combined the two interventions to see whether there was any difference in outcomes using both. Also they indicated that the subjects expressed an interest in getting off their sleep medication but there was no mention of whether this happened and whether there was any difference based on the intervention.

And for the first time, a 2016 study establishes an animal model for the NADA protocol supporting its use in the treatment of addiction. Kailasam et al compared the NADA points with five sham ear helix points on morphine dependent rats.60 Intradermal needles were inserted and maintained for 25–30 min per session for 6 days. They found that the NADA intervention reduced the phenomenon of repeated morphine dose-induced locomotor sensitization (which they correlate with craving), prevented the development of morphine tolerance; and shortened the time to analgesic effect of morphine as compared to the sham needles. Kailasam et al60 argued that their findings confirmed the appropriateness of the rat model and validated the reports of NADA-induced craving reduction in humans. They proposed that the NADA protocol might be effectively used along with opioid chronic pain management to improve analgesic onset and prevent dose escalation and therefore reduce adverse reactions. In this incidence, research may be pointing the way to new application of the NADA protocol as an adjunctive tool for opioid pain management.

NADA not just with needles: beads and seeds

Acupuncture is just one of the methods for stimulating auricular acupuncture points. Tapping Vaccaria seeds or magnetized metal beads to the points provides another avenue which has clinically evolved as both a more gentle intervention for fearful or extremely sensitive individuals and a more prolonged way to provide stimulation and support. NADA practitioners have used beads alongside needles clinically and for neonates, children with ADD/ADHD and in trauma/disaster situations, often using a single point bilaterally, Shen Men or the point directly behind it, “Reverse Shen Men” on the back of the ear. Despite its broad provider acceptance and anecdotal documentation, little peer-reviewed research has focused on this acupressure modality. However, in 2015, an RCT compared pressure on a seed on the Shen Men point twice daily added to usual post-cesarian section hospital care over 5 days. The researchers report significant differences between the acupressure group (n=39) and the usual care group (n=37) in anxiety and fatigue ratings on validated tools, as well as in heart rate and mean serum cortisol level decreases.61

Discussion

This review is a chronological look at studies and reports specifically of the use of the NADA protocol in addiction and behavioral health. The proliferation of use of the NADA protocol occurred as a grass-roots movement which had no research or financial backing but was stimulated by an opiate and cocaine epidemic in the 1980s. It was the positive anecdotal experiences reported by practitioners and patients (practice-based evidence) that led researchers to attempt to study it systematically. However, this treatment does not lend itself to the Western model of the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial because of the difficulty blinding both the recipient and the treatment provider and the fact that sham acupuncture has some effect. As other reviews have indicated and this review confirms, the aggregate of RCTs is not conclusively supportive of acudetox. The trials have been plagued by design flaws elucidated here and in former reviews. They vary from the reality of clinical practice and by active control groups. The NADA protocol involves a client-centered approach, 3–5 specific ear points, delivered in a group setting, with sufficient frequency (at least several times per week for several weeks), and always in conjunction with appropriate levels of usual psychosocial and/or medical care. Study designs that use different needle combinations, insufficient amounts of intervention, individual treatment, and “stand-alone” approach are not appropriate measures of acudetox. Recent RCT trials using usual care controls yielded more positive results. The broader pool of studies is generally more positive. Like the wide-ranging application of acudetox in the field, researchers have looked at NADA-style treatment with many different populations, within many different treatment settings/modalities, and looked at a wide range of outcome measures (Table 1). Although it does not have the compelling force of large replicated RCTs, the preponderance of small varied trails collectively paints a picture supporting acudetox as an “evidenced-based practice.”

Recommendations for Future NADA Studies

The NADA protocol appears to be an excellent tool to study the effects of acupuncture for many reasons. It is a standardized protocol that eliminates the need for an acupuncturist to make a differential diagnosis and determine the treatment points. It is an inexpensive intervention, with minimal side effects that can be readily transported anywhere and easily taught to a wide range of health care practitioners and integrated with almost all health care services.

In order to support acudetox as “evidence-based practice,” more research is necessary. Suggestions include the replication of studies that have been done with full body acupuncture to demonstrate effectiveness, using the NADA protocol in place of full body acupuncture. For example, Spence et al reported on an elegant pilot study of full body acupuncture for the treatment of insomnia in 18 anxious adults.62 They performed pre- and post-polysomnography, psychometric testing, and 24-h urine collection for melatonin. Five weeks of twice weekly full body acupuncture treatment was associated with a significant increase in endogenous melatonin and significant improvements in polysomnographic measures of sleep including onset latency, arousal index, total sleep time, and sleep efficiency. Significant reductions in state and trait anxiety scores were also found. Similar research done with the NADA protocol would be interesting.

Going forward, studies with usual care, non-sham, control groups might further investigate the benefits of NADA for substance treatment and rehabilitation, mental health, chronic pain, humanitarian aid, and chronic as well as acute trauma. Another possible mixed methods approach may be to systematize the collection of field reports by creating a passive collection system. Clients could access a common data collection system and respond to a common set of questions.

Conclusion

The NADA protocol developed in an era of rampant opiate use has always maintained a community and creativity focus as it has evolved into a tool for modern times with potential for broad application in behavioral health, criminal justice, trauma/disaster responses, and humanitarian aid. It may be that the appropriate evidence base for the NADA protocol is this very amassing of small, elegant trials that illuminate the various types of applications and outcomes. This review demonstrates the mounting evidence that the NADA protocol has positive effects on a host of measures, populations, and treatment modalities. It is striking that many of the studies reveal NADA’s effectiveness with populations often considered to be the most difficult to treat.

Arguably, large-scale replication trials would add credibility to the intervention, but the range of small positive studies offers testimony, perhaps more appropriate to the reality of NADA practice today. In research and clinical settings, acudetox is best understood as a psychosocial intervention augmenting other treatments matched to clients’ particular needs.

This is not a systematic review. This review does allow a history and a current look at what the published literature tells us about NADA as a supportive intervention, not only for substance abuse rehabilitation but also for many other health care and community wellness applications.

Disclosure

Both the authors are members of the NADA and Registered Trainers for the nonprofit organization. Dr Stuyt is the current Board President of the organization. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Alberto AD. Auricular acupuncture in the treatment of cocaine/crack abuse: a review of the efficacy, the use of the National Acupuncture Detoxification Association protocol, and the selection of sham points. J Altern Complement Med. 2004;10:985–1000. | ||

Lua PL, Talib NS. The effectiveness of auricular acupuncture for drug addiction: a review of research evidence from clinical trials. ASEAN J Psych. 2012;13:55–68. | ||

Lipton DS, Brewington V, Smith M. Acupuncture for crack-cocaine detoxification: experimental evaluation of efficacy. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1994;11(3): 205–215. | ||

Avants SK, Margolin A, Holford TR, Kosten TR. A randomized controlled trial of auricular acupuncture for cocaine dependence. Arch Int Med. 2000;160:2305–2312. | ||

Bullock ML, Kiresuk,TJ, Pheley AM, Culliton PD, Lenz SK. Auricular acupuncture in the treatment of cocaine abuse: a study of efficacy and dosing. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1999;16(1):31–38. | ||

Margolin A, Kleber HD, Avants SK, et al. Acupuncture for the treatment of cocaine addiction. JAMA. 2002;287(1):55–63. | ||

Otto KC, Quinn C, Sung YF. Auricular acupuncture as an adjunctive treatment for cocaine addiction. A pilot study. Am J Addict. 1998;7(2):164–170. | ||

Killeen TK, Haight B, Brady K, Herman J, Michel Y, Stuart G, Young S. The effect of auricular acupuncture on psychophysiological measures of cocaine craving. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2002;23:445–459. | ||

Margolin A, Avants SK, Holford TR. Interpreting conflicting findings from clinical trials of auricular acupuncture for cocaine addiction: does treatment context influence outcome? J Altern Complement Med. 2002;8(2):111–121. | ||

Washburn AM, Fullilove RE, Fullilove MT, et al. Acupuncture heroin detoxification: a single-blind clinical trial. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1993;10:345–351. | ||

Berman AH, Lundberg U, Krook AL, Gyllenhammar C. Treating drug using prison inmates with auricular acupuncture: a randomized controlled trial. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2004;26:95–102. | ||

Bearn J, Swami A, Stewart D. Auricular acupuncture as an adjunct to opiate detoxification treatment: effects on withdrawal symptoms. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;36:345–349. | ||

White A. Trials of acupuncture for drug dependence: a recommendation for hypotheses based on the literature. Acupunct Med. 2013;31:297–304. | ||

Moffet HH. Sham acupuncture may be as efficacious as true acupuncture: a systematic review of clinical trials. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15:213–216. | ||

Wan L. Complementary and alternative medical treatments: can they really be evaluated by randomized controlled trials? Acupunct Med. 2016;34(5):410–411. | ||

Gori L, Firenzuoli F. Ear acupuncture in traditional European medicine. eCAM. 2007;4(S1):13–16. | ||

Wen HL, Cheng SYC. Treatment of drug addiction by acupuncture and electrical stimulation. Asian J Med. 1973;9:138-141. | ||

Mitchell ER. Fighting Drug Abuse with Acupuncture. Berkeley, CA: Pacific View Press; 1995. | ||

Omura Y, Smith M, Wong F, et al. Electro-acupuncture for drug addiction withdrawal. Acupunct Electro-Therap Res Intern J. 1975;1:231–233. | ||

National Acupuncture Detoxification Association. Acupuncture Detoxification Specialist Training Resource Manual. 4th ed. Wyoming: Laramie; 2011. | ||

Smith MO, Squires R, Aponte J, Rabinowitz N, Bonilla-Rodriguez R. Acupuncture treatment of drug & alcohol abuse: 8 years’ experience emphasizing tonification rather than sedation. Am J Acup. 1982;10:161–163. | ||

National Acupuncture Detoxification Association. Available from: www.acudetox.com. Accessed July 1, 2016. | ||

Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment. Services (N-SSATS); 2012. Available from: http://wwwdasis.samhsa.gov/dasis2/nssats/2012_nssats_rpt.pdf. Accessed November 22, 2016. | ||

Acupuncturists without Borders. Available from: www.acuwithoutborders.org. Accessed July 1, 2016. | ||

Colorado Acupuncture Medical Reserve Corps. Available from: http://acucol.com/acupuncture-medical-reserve-corp/. Accessed July 1, 2016. | ||

Bullock ML, Umen AJ, Culliton PD, Olander RT. Acupuncture treatment of alcoholic recidivism: a pilot study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1987;11(3):292–295. | ||

Bullock M L, Culliton PD, Olander RT. Controlled trial of acupuncture for severe recidivist alcoholism. Lancet. 1989;1:1435–1439. | ||

Brewington V, Smith M, Lipton D. Acupuncture as a detoxification treatment: an analysis of controlled research. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1994;11(4):289–307. | ||

Gurevich MI, Duckworth D, Imhof JE, Katz JL. Is auricular acupuncture beneficial in the inpatient treatment of substance-abusing patients?: a pilot study. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1996;13(2):165–171. | ||

Konefal J, Duncan R, Clemence C. The impact of the addition of an acupuncture treatment program to an existing metro-dade county outpatient substance abuse treatment facility. J Addict Dis. 1994;13(3):71–99. | ||

Avants KS, Margolin A, Chang P, Kosten TR, Birch S. Acupuncture for the treatment of cocaine addiction: investigation of a needle puncture control. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1995;12(3):195–205. | ||

Richard AJ, Montoya ID, Nelson R, Spence RT. Effectiveness of adjunct therapies in crack cocaine treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1995;12:401–413. | ||

Wells EA, Jackson R, Diaz OR, Stanton V, Saxon AJ, Krupsko A. Acupuncture as an adjunct to methadone treatment services. Am J Addict. 1995;4:198–214. | ||

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Detoxification from Alcohol and Other Drugs Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 19. DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 95-2046; 1995. | ||

National Institutes of Health Consensus Statement. Acupuncture. 1997;15(5):1–34. | ||

Shwartz M, Saitz R, Mulvey K, Brannigan P. The value of acupuncture detoxification programs in a substance abuse treatment system. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1999;17(4):305–312. | ||

Bier ID, Wilson J, Studt P, Shakleton M. Auricular acupuncture, education, and smoking cessation: a randomized, sham-controlled trial. Am J Pub Health. 2002;92(1):1642–1647. | ||

Berman AH, Lundberg U. Auricular acupuncture in prison psychiatric units: a pilot study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106:152–157. | ||

Janssen PA, Demorest LC, Whynot EM. Acupuncture for substance abuse treatment in the downtown eastside of Vancouver. J Urban Health. 2005;82(2):285–295. | ||

Santasiero RP, Neussle G. Cost-effectiveness of auricular acupuncture for treating substance abuse in an HMO setting: a pilot study. Med Acupunct. 2005;16(3):39–42. | ||

Stuyt EB, Meeker JL. Benefits of auricular acupuncture in tobacco-free inpatient dual-diagnosis treatment. J Dual Diagn. 2006;2(4):41–52. | ||

Yarberry M. The use of the NADA protocol for PTSD in Kenya. Ger J Acup Rel Techniques. 2010;53: 6–11. | ||

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Detoxification and Substance Abuse Treatment. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 45. DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 06-4131; 2006. | ||

Brumbaugh A. Acudetox: Lost, Stolen or Strayed? The NADA Ear Acupuncture Protocol. Laramie, WY: NADA Literature Clearinghouse; 2016. | ||

Cowan D. Methodological issues in evaluating auricular acupuncture therapy for problems arising from the use of drugs and alcohol. Acupunct Med. 2011;29(3):227–229. | ||

Carter KO, Olshan-Perlmutter M, Norton HJ, Smith MO. NADA acupuncture prospective trial in patients with substance use disorders and seven common health symptoms. Med Acupunct. 2011;23(3):131–135. | ||

Black S, Carey E, Webber A, Neish N, Gilbert R. Determining the efficacy of auricular acupuncture for reducing anxiety in patients withdrawing from psychoactive drugs. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2011;41(3):279–287. | ||

Janssen PA, Demorest LC, Kelly A, Thiessen P, Abrahams R. Auricular acupuncture for chemically dependent pregnant women: a randomized controlled trial of the NADA protocol. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy.2012;7:48. | ||

Chang BH, Sommers E. Acupuncture and relaxation response for craving and anxiety reduction among military veterans in recovery from substance use disorder. Am J Addict. 2014;23:129–136. | ||

Stuyt EB. Ear acupuncture for co-occurring substance abuse and borderline personality disorder: an aid to encourage treatment retention and tobacco cessation. Acupunct Med. 2014;32:318–324. | ||

Stuyt EB. Enforced abstinence from tobacco during in-patient dual-diagnosis treatment improves substance abuse outcomes in smokers. Am J Addict. Epub 2014 Dec 3. | ||

Samuel DB, LaPaglia DM, Maccarelli LM, Moore BA, Ball SA. Personality disorders and retention in therapeutic community for substance dependence. Am J Addict. 2011;20:555–562. | ||

Daughters SB, Lejuez CW, Borovalowa MA, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Brown RA. Distress tolerance a predictor of early treatment dropout in a residential substance abuse treatment facility. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005;114:729–734. | ||

Bergdahl L, Berman AH, Haglund K. Patients’ experience of auricular acupuncture during protracted withdrawal. J Psych Men Health Nurs. 2014;21:163–169. | ||

Reilly PM, Buchanan TM, Vafides C, Breakey S, Dykes P. Auricular acupuncture to relieve health care workers’ stress and anxiety. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2014;33(3):151–159. | ||

Carter KO, Olshan-Perlmutter M. Impulsivity and stillness: NADA, pharmaceuticals, and psychotherapy in substance use and other DSM 5 disorders. Behav Sci. 2015;5:537–546. | ||

De Lorent L, Agorastos A, Yassouridis A, Kellner M, Muhtz C. Auricular acupuncture versus progressive muscle relaxation in patieants with anxiety disorders or major depressive disorder: a prospective parallel group clinical trial. J Acupunct Meridian Stud. 2016;9:191–199. | ||

Ahlberg R, Skarberg K, Brus O, Kjellin L. Auricular acupuncture for substance use: a randomized controlled trial of effects on anxiety, sleep, drug use and use of addiction treatment services. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2016;11:24. | ||

Bergdahl L, Broman JE, Berman AH, Haglund K, von Knorring L, Markstrom A. Auricular acupuncture and cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep Disord. 2016;2016:7057282. | ||

Kailasam VK, Anand P, Melyan Z. Establishing an animal model for National Acupuncture Detoxification Association (NADA) auricular acupuncture protocol. Neurosci Lett. 2016;624:29–33. | ||

Kuo SY, Tsai SH, Chen SL, Tzeng YL. Auricular acupressure relieves anxiety and fatigue, and reduces cortisol levels in post-cesarean section women: a single-blind, randomized controlled study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;53:17–26. | ||

Spence DW, Kayumov L, Chen A, et al. Acupuncture increases nocturnal melatonin secretion and reduces insomnia and anxiety: a preliminary report. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;16:19–28. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.