Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

The Influence of Social Exclusion on High School Students’ Depression: A Moderated Mediation Model

Authors Yu X, Du H, Li D, Sun P, Pi S

Received 30 August 2023

Accepted for publication 27 October 2023

Published 22 November 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 4725—4735

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S431622

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Einar Thorsteinsson

Xinxin Yu,1 Haixin Du,1 Dongyan Li,1 Peizhen Sun,2 Shiyi Pi1

1Department of Psychology, Guangxi Normal University, Guilin, 541004, People’s Republic of China; 2Department of Psychology, Jiangsu Normal University, Xuzhou, 221116, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Dongyan Li; Peizhen Sun, Email [email protected]; [email protected]

Purpose: High school students face various pressures such as academic and interpersonal relationships, which can easily lead to depression. Social exclusion is one of the important influencing factors for adolescent depression, but there is still limited research on the mechanisms of the impact that social exclusion has on depression. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the effect of social exclusion on depression among high school students, as well as the mediating role of thwarted belongingness and the moderating role of cognitive reappraisal.

Methods: Researchers assessed 1041 high school students using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), Adolescent Social Exclusion Scale, Interpersonal Needs Scale, and Emotion Regulation Scale.

Results: (1) Social exclusion was negatively associated with cognitive reappraisal (r = − 0.224, p < 0.001), and positively associated with thwarted belongingness and depression (r = 0.657, 0.490, p < 0.001). Thwarted belongingness was positively associated with depression (r = 0.617, p < 0.001), and negatively associated with cognitive reappraisal (r = − 0.325, p < 0.001). Cognitive reappraisal was negatively associated with depression (r = − 0.280, p < 0.01). (2) Social exclusion could directly predict depression, 95% CI [0.08, 0.21]. Thwarted belongingness played a partial mediating role between social exclusion and depression, 95% CI [0.30, 0.40]. (3) Cognitive reappraisal moderated the predictive effect of thwarted belongingness on depression.

Conclusion: Social exclusion can influence depression through thwarted belongingness and cognitive reappraisal, and educators can reduce depression by decreasing thwarted belongingness and promoting the use of cognitive reappraisal strategies by high school students.

Keywords: high school students, social exclusion, thwarted belongingness, cognitive reappraisal, depression

Introduction

High school is a stressful and crisis-prone time. Teenagers at this stage are more likely to have various emotional and behavioral problems. Depression is an ineffective stress response to the pressure of study, life, or work, which is often accompanied by emotional problems, including a range of physical and mental symptoms such as low mood, despair, helplessness, and worthlessness.1 A 2019–2020 report on national mental health development in China pointed out that the detection rate of depression among adolescents in 2020 was 24.6%.2 According to research findings, depression is a significant cause of low academic achievement, behavioral problems, and suicide risk among adolescents.3–5 Depression in adolescence can predict poor psychological functioning later in life and increase the risk of depression and suicide in adulthood.6 Therefore, it is particularly important to study the factors underlying depression in teenagers.

Social exclusion has a serious negative impact on teenagers’ mental health, which increases the risk of adolescent depression. In recent years, an increasing number of researchers have discussed the impact that social exclusion can have on mental health.7–9 Despite this, there is still limited research on the mechanisms of the impact that social exclusion has on depression. The ABC emotion theory believes that there is no distinction between good and bad events themselves, but rather that people assign subjective emotions to the event, which leads to negative emotions such as depression.10 According to the needs-threat time model of social exclusion, social exclusion threatens the satisfaction of basic needs such as belonging.9 The current study is based on the need-threat time model and the emotional ABC theory. It aims to explore the mediating effect of thwarted belongingness between social exclusion and depression and the moderating effect of cognitive reappraisal on the relationship between thwarted belongingness and depression. This study not only helps to enrich the relevant research on the influence of social exclusion on senior high school students’ depression but also provides a feasible direction to reduce the occurrence of depression among high schoolers.

Social Exclusion and Depression

Social exclusion refers to the process by which an individual’s social relationships and sense of belonging are thwarted because they are excluded by other people.11 Social exclusion has a significant impact on cognition, emotion, and behavior.12 When studying social exclusion, scholars have found that being excluded from society would threaten the individual’s psychological needs, namely the sense of belonging, self-esteem, and meaningful existence.13 The excluded person will feel lonely, have a sense of meaninglessness and have negative emotional reactions, even depression.14,15

According to the social cognitive theory of depression, depression is affected by environmental factors and individual factors.16 Social exclusion is considered an environmental factor that can lead to depression. Due to a lack of support and attention, people suffering from social exclusion lack a sense of belonging and are more likely to experience depression and anxiety.17 This was illustrated during the COVID-19 pandemic, in which social exclusion lead to a high prevalence of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents.18 Therefore, this study proposes Hypothesis 1: Social exclusion is positively related to depression.

The Mediating Role of Thwarted Belongingness Between Social Exclusion and Depression

Researchers have studied the impact of social exclusion on an individual’s sense of belonging and the development of physical and mental health.19 If rejected by others or groups, the individual’s sense of belonging will be lost, and the individual will feel helpless in interpersonal relationships, which can easily lead to psychological adjustment problems.20 Thwarted belongingness is a concept that describes interpersonal functioning characterized by loneliness and lack of social connection. It is regarded as a manifestation of an individual’s unmet interpersonal needs.21 Social exclusion is closely related to thwarted belongingness.22 Thwarted belongingness may be the underlying mechanism that links negative events to depression. It significantly positively predicts depression and a greater neural response to new social exclusion.23,24 According to the theory of interpersonal relationships, interpersonal problems have a significant impact on the onset and persistence of depression.25,26 Thwarted belongingness reflects disharmony in an individual’s interpersonal relationships, affects the individual’s psychological and social adjustment, and further increases the risk of depression. Therefore, this study proposes Hypothesis 2: Thwarted belongingness plays a mediating role between social exclusion and depression.

The Moderating Effect of Cognitive Reappraisal on the Relationship Between Thwarted Belongingness and Depression

Cognitive reappraisal is an emotion regulation strategy that refers to an individual’s ability to mentally reframe negative events to reduce their impact.27 According to the emotional ABC theory, an individual’s negative emotions are caused by an incomplete evaluation of the stress source.10 Studies have shown that cognitive reappraisal partially mediates the relationship between loneliness and depression,28 so it could serve to influence the relationship between thwarted belongingness and depression as well. In addition, cognitive reappraisal can effectively alleviate the negative impact that depressive symptoms have on perceptions of social support.29 Because of this, cognitive reappraisal may be an effective strategy for adolescents to alleviate depressive symptoms and related emotional responses.30 Therefore, this study proposes Hypothesis 3: Cognitive reappraisal has a moderating effect on thwarted belongingness and depression.

This study constructs a moderated mediation model (Figure 1) to explain the influence of social exclusion on depression and the underlying mechanism of thwarted belongingness and cognitive reappraisal. It aims to provide a new theoretical perspective on the factors underlying depression and to propose methods that would reduce depression among high school students and promote their healthy development.

|

Figure 1 A moderated mediation model. |

Methods

Participants

The survey was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethical Committee of Guangxi Normal University and all participants provided informed consent. Participants were selected with cluster sampling method with the class as a sampling unit from three high schools in Guangxi and Jiangxi in China. After deleting 109 data who answered the same number on the entire questionnaires, we obtained 1041 (90.5%) valid responses. There were 548 males (52.6%) and 493 females (47.4%), 460 first-year students (44.2%) and 581 second-year students (55.8%), 450 urban students (43.2%) and 591 rural students (56.8%). The age range was 16–17 years (M = 16.59, SD = 0.76).

Research Tools

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)

The frequency of depressive symptoms individuals experienced in the week prior to participating in the study was measured by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) compiled by Radloff and revised by Chen Zhiyan.31,32 The scale consists of 20 items, and the reverse scoring questions are 4, 8, 12, and 16. It includes four factors: depression, positive emotions, somatic symptoms, and interpersonal relationships. The CES-D uses a 4-point scoring method, with answers ranging from “occasionally or never (less than 1 day)” to “most of the time or duration (5–7 days).” Each answer counts as 0–3 points respectively, with total scores ranging from zero to 60. The higher the total score, the greater the experience of depressive symptoms. Cronbach’s coefficient for the scale was 0.84.

Adolescent Social Exclusion Scale

The Chinese version of the Adolescent Social Exclusion Scale revised by Zhang et al was used in this study.33 The scale has a total of 11 items encompassing two dimensions, which are rejection and neglect. It uses a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 represents “completely inconsistent” and 5 represents “completely consistent.” The reverse scoring questions are 1, 3, 4, 5, 7, and 9. Higher total scores indicate more intense feelings of rejection. Cronbach’s coefficient for the scale was 0.78.

Interpersonal Needs Scale

The Interpersonal Needs Scale compiled by Van Orden et al and revised by Li et al was used. It includes a total of 15 items covering two dimensions: thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness.21,34 The reverse scoring questions are 1, 4, 5, 8, 9, and 13. The scale adopts a seven-point scoring method, with 1 meaning “completely incorrect” and 7 meaning “completely correct.” Higher scores indicate greater thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness. In the current study, the thwarted belongingness dimension of the Interpersonal Needs Scale was used to measure the participants’ levels of thwarted belongingness. The higher the score, the higher the individual’s level of thwarted belongingness. Cronbach’s coefficient for the thwarted belongingness dimension of the Interpersonal Needs Scale was 0.87.

Emotion Regulation Scale

The Emotion Regulation Scale was compiled by Gross and John and revised by Wang et al.35,36 The scale has a total of 10 items that make up the dimensions of cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression. Among them, six items (1, 3, 5, 7, 8, and 10) measure cognitive reappraisal, and four items (2, 4, 6, 9) measure expressive suppression. In this study, the six items of the cognitive reappraisal dimension were used to measure the cognitive reappraisal ability of high school students. The scale adopts a seven-point scoring method, with 1 meaning “strongly disagree” and 7 representing “strongly agree.” Higher total scores indicate more frequent use of cognitive reappraisal. Cronbach’s coefficient for the Emotion Regulation Scale’s cognitive reappraisal dimension was 0.853.

Results

Common Method Bias Test

The research data is based on self-reports. Harman’s single-factor test was used to control the common method bias of the survey. The results showed that there were nine factors with a characteristic root greater than 1, and the variation interpretation rate of the first factor was 24.687%, not more than 40% of the critical value. Therefore, the results showed that there is no serious common method bias in this study.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

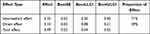

The average value, standard deviation, and Pearson correlation coefficient of the main variables in the study are shown in Table 1. Social exclusion was positively related to thwarted belongingness and depression, but negatively related to cognitive reappraisal. There was a significant positive correlation between thwarted belongingness and depression, but a significant negative correlation between thwarted belongingness and cognitive reappraisal. There was a significant negative correlation between cognitive reappraisal and depression.

|

Table 1 The Results of Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis |

Mediating Effect Test

In this study, Model 4 of PROCESS 3.5, a plug-in of SPSS 22.0 compiled by Hayes, was used to test the mediation effect of thwarted belongingness. The test used social exclusion as the independent variable, depression as the dependent variable, and thwarted belongingness as the mediator variable. Gender and age were used as control variables to test the mediating effect of thwarted belongingness between social exclusion and depression. The results are shown in Table 2.

|

Table 2 The Mediating Model Test of Social Exclusion on Depression (N=1041) |

According to the results in Table 2, after controlling for gender and age, social exclusion was a positive predictor of depression in high school students (β = 0.50, t = 18.19, p < 0.001). Social exclusion also positively predicted the thwarted belongingness of high school students (β = 0.66, t = 28.10, p < 0.001). Thwarted belongingness positively predicted depression in high school students (β = 0.53, t = 16.60, p < 0.001), and after including thwarted belongingness as a mediator variable, social exclusion still significantly, positively predicted the depression of high school students (β = 0.14, t = 4.50, p < 0.001). Hypothesis 1 was supported.

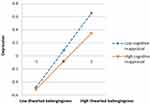

The Bootstrap method was used to further evaluate the mediating effect value. The results (shown in Table 3) showed that the effect values in the Bootstrap 95% confidence interval did not include 0. The results showed that the social exclusion of high school students not only had a direct effect on depression but also had an indirect effect on depression through thwarted belongingness. The direct effect accounted for 29% of the total effect, with a value of 0.14 (Figure 2). The mediating effect value was 0.35, and the mediating effect accounted for 71% of the total effect. In other words, thwarted belongingness plays a partially mediating role between social exclusion and depression. Hypothesis 2—that thwarted belongingness has a significant mediating effect on social exclusion and depression among high school students—was supported by these results.

|

Table 3 The Mediating Effect Size of Thwarted Belongingness Between Social Exclusion and Depression (N=1041) |

|

Figure 2 The roadmap of the mediating effect of thwarted belongingness between social exclusion and depression. ***p<0.001. |

Moderated Mediating Effect Test

To explore the effect of cognitive reappraisal in the mediation model, PROCESS 3.3, a plug-in of SPSS, was used to further assess the moderating effect of cognitive reappraisal between thwarted belongingness and depression. Model 14 of PROCESS was used to test the moderated mediation model in this study. In the test, all variables were standardized. Gender and age were used as control variables. First, social exclusion and depression were used as independent and dependent variables for statistical analysis, respectively. Further statistical analysis was performed, with social exclusion, thwarted belongingness, cognitive reappraisal, and the interaction between thwarted belongingness and cognitive reappraisal entered as independent variables, and depression entered as a dependent variable. The results are shown in Table 4.

|

Table 4 Moderated Mediation Model Analysis (N=1041) |

The test results show that social exclusion significantly predicted thwarted belongingness (β = 0.66, t = 28.10, p < 0.001) and depression (β = 0.15, t = 4.60, p < 0.001). Thwarted belongingness significantly positively predicted depression (β = 0.50, t = 15.34, p < 0.001). In contrast, cognitive reappraisal significantly negatively predicted depression (β = −0.08, t = −3.36, p < 0.001). Finally, the interaction between thwarted belongingness and cognitive reappraisal significantly negatively predicted depression (β = −0.07, t = −3.44, p < 0.001), indicating that cognitive reappraisal moderated the predictive effect of thwarted belongingness on depression. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was supported. Thus, the four variables of social exclusion, depression, thwarted belongingness and cognitive reappraisal form a moderated mediation model. Thwarted belongingness has a mediating effect between social exclusion and depression, while cognitive reappraisal moderates this effect.

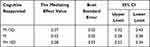

Through simple slope analysis, we further investigated the predictive effect of thwarted belongingness on the depression of high school students under different cognitive reappraisal conditions (using a positive and negative standard deviation). A simple slope analysis chart was constructed, as shown in Figure 3.

|

Figure 3 Simple slope test of cognitive reappraisal as a moderating variable between thwarted belongingness and depression. |

Figure 3 shows that under the condition of low cognitive reappraisal, thwarted belongingness had a significant positive predictive effect on the depression of high school students (Bsimple = 0.57, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.50, 0.63). The higher the thwarted belongingness, the higher the depression of the students. Under the condition of high cognitive reappraisal, although thwarted belongingness still had a positive predictive effect on depression, its predictive effect was mitigated (Bsimple = 0.42, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.35, 0.51]. As cognitive reappraisal improved, the predictive effect of thwarted belongingness on depression gradually weakened, as shown in Table 5.

|

Table 5 The Mediating Effect of Thwarted Belongingness on Social Exclusion and Depression at Different Levels of Cognitive Reappraisal |

Discussion

Social Exclusion and Depression

The results of this study show that there is a significant positive relationship between social exclusion and depression, which supports Hypothesis 1. This is consistent with the conclusions of earlier research,37 which also indicate that the greater the individual’s perception of social exclusion, the higher the level of depression they experience.38 According to the social cognitive theory of depression, depression is caused by the interaction between individual characteristics and the external environment. Social exclusion, interpersonal pressures, and negative life events are important external situational factors that contribute to depression.16 Researchers have investigated the relationship between social exclusion, interaction anxiousness, and depression. They found that there is a positive correlation between these factors,39 and it is especially strong for children and adolescents. Social exclusion, as an indicator of negative interpersonal relationships, can contribute to interaction anxiousness. This can evoke negative emotions such as loneliness and despair, and can ultimately lead to depression. Individuals can feel excluded by family, peers, teachers, and other groups, and the sense of inferiority and alienation that this can evoke is especially damaging to teenagers. Social exclusion leads to higher levels of cortisol and poorer cognitive development. Preventing young people from feeling inferior should reduce the harm of social exclusion and strengthen the cultivation of interpersonal relationships.40

The Mediating Effect of Thwarted Belongingness Between Social Exclusion and Depression

This study found that thwarted belongingness plays a partial mediating role between social exclusion and depression among high school students. Social exclusion increases the risk of depression among high school students through thwarted belongingness, supporting Hypothesis 2. First, social exclusion is positively correlated with thwarted belongingness, which is consistent with previous studies.41 According to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Theory, the need to belong—that is, to maintain meaningful, enduring, and high-quality relationships with others—is a basic human need.42 Furthermore, basic psychological needs theory also suggests that social exclusion poses a serious threat to an individual’s need for relatedness.43 Therefore, the basic needs of individuals are compromised when they suffer from social exclusion.44 Belonging is one of the most significant goals that people pursue. If the need to belong is not met, it has a significant impact on an individual’s cognition, and emotional and physical health.42 Furthermore, a student’s sense of belonging in school is an important variable affecting their academic performance and happiness, and these areas are negatively impacted if the need to belong is not met.45 When faced with social exclusion at school, high school students experience distress in a variety of ways. Second, thwarted belongingness is positively correlated with depression.46 When a person is deprived of a sense of belonging, it may lead to elevated levels of stress, anxiety, depression, and other negative emotions. Previous studies have found that a sense of belonging plays a role in how interpersonal relationships influence individual mental health. Healthy interpersonal relationships promote positive interactions between individuals and help to support mental health.47 On the contrary, if an individual does not have a sense of belonging, it is not conducive to their positive development. It can easily create a powerful sense of loneliness and lead to depression, self-harm, and even suicidal tendencies. This means that thwarted belongingness plays a mediating role between social exclusion and depression.48 According to the interpersonal relationship theory of depression, interpersonal problems have a significant impact on the onset and persistence of depression.26 Thwarted belongingness reflects the disruption of interpersonal functioning, which affects the individual’s psychological and social adaptability, exacerbating the risk of depression.

The Moderating Effect of Cognitive Reappraisal Between Thwarted Belongingness and Depression

This study found that cognitive reappraisal had a significant moderating effect on thwarted belongingness and depression, supporting Hypothesis 3. Cognitive reappraisal indirectly affects the depression of high school students by modulating thwarted belongingness but does not directly impact depression. Compared to individuals with low levels of cognitive reappraisal, individuals with high levels of cognitive reappraisal can buffer the effects of thwarted belongingness on depression. In other words, the stronger the individual’s ability to master cognitive reappraisal strategies, the weaker the impact of thwarted belongingness on depression.

According to the cognitive theory of emotion, individual cognition plays an important role in the generation of emotions, which is also the theoretical basis for the generation of cognitive reappraisal. Specifically, the two-factor theory of emotion, appraisal-excitation theory, and cognitive appraisal theory are representative theoretical views, all of which emphasize the role of individual cognition in emotion generation.49 According to the emotional regulation model of cognitive reappraisal, cognitive reappraisal, a common emotional regulation strategy, can help individuals to think about the meaning and significance of the situation causing psychological distress from a long-term perspective, thereby reducing the negative impact of the sources of distress.50 Cognitive reappraisal can also help individuals to adjust their evaluation of self-cognition, identify the possible positive consequences of events, and thus change their view of negative life events to reduce psychological distress.51 Studies have shown that cognitive reappraisal can help people interpret events that cause negative emotions such as frustration, anger, and disgust more positively and reduce the experience and behavioral expression of negative emotions.52

When exploring why cognitive reappraisal strategies mitigate the effects of thwarted belongingness on depression, it is important to consider that cognitive reappraisal can arouse positive emotions even when an individual is facing adverse events, and allow the events to be evaluated from a positive perspective, thus reducing their negative impact. As mentioned previously, cognitive reappraisal can allow individuals to take a long-term view of events. Even if they cannot do anything about the stressor itself, this can reduce the impact of negative emotions. Furthermore, cognitive reappraisal can help individuals find the positive aspects of negative events and reduce the psychological distress that the events cause through positive cognition.53 In general, the more individuals use cognitive reappraisal, the more comprehensive and specific their self-evaluations will be. This can increase their perception of support from society, family, and school. Students with high cognitive reappraisal can change their understanding of negative emotional events and think about them from an objective and positive perspective, thus reducing the experience of negative emotions and increasing the experience of positive emotions. That is, the cognitive reappraisal strategy can feelings of thwarted belongingness and depression. Research supports that improving the cognitive reappraisal strategies of high school students helps alleviate depression and that cognitive reappraisal can be used as a protective factor against vulnerability to depression.52,54 We can resist depression by improving cognitive reappraisal and reducing expression suppression.55

Limitations and Contributions

This study has the following limitations. Firstly, the cross-sectional design of this study did not allow the causality between social exclusion, thwarted belongingness, cognitive reappraisal, and depression to be explored. Therefore, future research must investigate the causality between the relevant variables using a longitudinal design or an experiment. Secondly, the questionnaire data in this study were obtained by self-assessment, which may introduce a common method bias. In the future, it will be necessary to collect data from multiple sources, such as individuals, peers, parents, and teachers, and to check that the results are consistent across different measurement methods. Thirdly, the samples for this study came from two different regions, and there was an imbalance between urban and rural populations. It remains to be seen whether the research findings can be extended to other populations. In the future, researchers should collect data from the entire country to promote the generalizability of the research findings. Fourthly, the study obtained samples through cluster sampling method, which may cause sampling errors. Finally, this study did not examine the economic status of the participants’ families and ethnic background, which may have influenced the results of the study. Future studies can verify the conclusions of the current study by controlling for economic status and ethnic background.

Although this study has the above limitations, it also has the following contributions. From a theoretical perspective, this study enriched the extant literature by revealing the mediating role of thwarted belongingness and the moderating role of cognitive reappraisal and deepened the current understanding of the mechanism of social exclusion on depression. In addition, this study supports the cognitive theory of emotion and the emotion regulation model of cognitive reappraisal.34,50 From a practical point of view, this discussion on the formation mechanism of high school students’ depression is conducive to the design and implementation of intervention programs that aim to reduce high school students’ depression. First, identifying the mediating role of thwarted belongingness shows educators that reducing feelings of thwarted belongingness among students may help to reduce depression. Schools can help individuals build a good social support system and enhance a sense of belonging through group sandplay.56 Second, the moderating role of cognitive reappraisal suggests that intervention programs should focus on individuals with low cognitive reappraisal. Schools could further help individuals improve their cognitive reappraisal strategies through group counseling.

Conclusion

The present study found the following conclusions: (1) Social exclusion could significantly positively predict depression in high school students. (2) Thwarted belongingness played a partially mediating role between social exclusion and depression. (3) Cognitive reappraisal moderated the predictive effect of thwarted belongingness on depression. Specifically, cognitive reappraisal could buffer the negative effect of thwarted belongingness on high school students’ depression.Educators can reduce depression by decreasing thwarted belongingness and promoting the use of cognitive reappraisal strategies by high school students.

Data Sharing Statement

All data included in the current study can be obtained from the corresponding authors through their email address upon reasonable request.

Ethics Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethical Committee of Guangxi Normal University. We have obtained the informed consent from the study participants and the parents/legal guardians.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the editor and the anonymous reviewers for their useful comments on earlier drafts.

Funding

“Research and Practice of Online and Offline Mixed Teaching of Psychological Health Education Based on PBL”, Education Reform Project of Psychology Major Teaching Steering Committee of Ministry of Education (20221050).The research was supported by Humanity and Social Science Youth Foundation of Ministry of Education of China (21YJC190014), the Key Projects of the 13th Five-Year Plan for Education Science of Jiangsu Province (B-a/2020/01/11), Project of Philosophy and Social Science Research in Colleges and Universities in Jiangsu Province (2021SJA1044).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Liu Y, Zhang N, Bao G, et al. Predictors of depressive symptoms in college students: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Affect Disord. 2019;244:196–208. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2018.10.084

2. Fu X, Zhang K, Chen X. Report on National Mental Health Development in China (2019–2020). Social Sciences Academic Press (China) 2021.

3. Diaconu-Gherasim LR, M Ă Irean C. Depressive symptoms and academic achievement: the role of adolescents’ perceptions of teachers’ and peers’ behaviors. J Res Adolesc. 2020;30(2):471–486. doi:10.1111/jora.12538

4. Blain-Arcaro C, Vaillancourt T. Longitudinal associations between externalizing problems and symptoms of depression in children and adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2019;48(1):108–119. doi:10.1080/15374416.2016.1270830

5. Kang N, You JN, Huang JY, Ren YX, Lin MP, Xu SA. Understanding the pathways from depression to suicidal risk from the perspective of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2019;49(3):684–694. doi:10.1111/sltb.12455

6. Sun H, Xu F, Liu Y, et al. Parental expectation and internalizing problem behavior in early and middle adolescence: a differentiated mediating model. Psychol Res. 2018;11(6):556–562.

7. Xue Z, Hao J, Ren Z, Yan D, Wang L, Yuan J. The urban-rural differences in the influence of social exclusion on suicide ideation: an empirical study based on implicit and explicit evaluation. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2022;6:1382–1388.

8. Wang Y, Chen H, Yuan Y. Effect of social exclusion on adolescents’ self-injury: the mediation effect of shame and the moderating effect of cognitive reappraisal. Acta Psychologica Sinica. 2020;43(2):333–339.

9. Liu C, Dong Y, Wang H, Zhang D. Social exclusion experience and health condition among the rural elders: the moderated mediating effect. Psychol Dev Educ. 2021;37(5):752–760.

10. Yu P. Effect of emotional ABC theory on anxiety and depression of breast cancer patients. Matern Child Health Care China. 2015;24:4107–4109.

11. Du J, Xia B. The psychological view on social exclusion. Adv Psychol Sci. 2008;16(6):981–986.

12. Fan M, Jie J, Luo P, et al. Social exclusion down-regulates pain empathy at the late stage of empathic responses: electrophysiological evidence. Front Hum Neurosci. 2021;15:634714. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2021.634714

13. Reddy LF, Irwin MR, Breen EC, Reavis EA, Green MF. Social exclusion in schizophrenia: psychological and cognitive consequences. J Psychiatr Res. 2019;114:120–125. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.04.010

14. Aghakhani H, Main KJ. Can two negatives make a positive? Social exclusion prevents carryover effects from deceptive advertising. J Retail Consum Serv. 2019;47:206–214. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.11.021

15. Kawada T. Depression and social isolation in the young. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2021;209(1):88. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000001225

16. Beck AT. Cognitive models of depression. Cogn Psychother. 1987;1(1):5–37.

17. Bibi R, Kazmi SF, Pervaiz T, Bashir R. The mental health issues of eunuchs in the context of social exclusion. J Pak Med Assoc. 2021;71(2(B)):578–584. doi:10.47391/JPMA.887

18. Deolmi M, Pisani F. Psychological and psychiatric impact of COVID-19 pandemic among children and adolescents. Acta Bio Med. 2020;91(4):e2020149. doi:10.23750/abm.v91i4.10870

19. Zamperini A, Menegatto M, Mostacchi M, Barbagallo S, Testoni I. Loss of close relationships and loss of religious belonging as cumulative ostracism: from social death to social resurrection. Behav Sci (Basel). 2020;10(6):99. doi:10.3390/bs10060099

20. Liu Y, Ma D, Du Y, Liu X, Zhao J, Zhang S. Hoarding behavior on depression in college students: the multiple chain mediating effects of social exclusion, thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2021;29(5):1050–1054.

21. Van Orden KA, Cukrowicz KC, Witte TK, Joiner TE. Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness: construct validity and psychometric properties of the interpersonal needs questionnaire. Psychol Assess. 2012;24(1):197–215. doi:10.1037/a0025358

22. O’Reilly J, Robinson SL. The negative impact of ostracism on thwarted belongingness and workplace contributions//Academy of management proceedings. Acad Manage J. 2009;1:1–7.

23. Chen H, Li X, Li B, Huang A. Negative trust and depression among female sex workers in Western China: the mediating role of thwarted belongingness. Psychiatry Res. 2017;256:448–452. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2017.06.031

24. Albanese BJ, Capron DW, Macatee RJ, Bauer BW, Schmidt NB. Thwarted belongingness predicts greater neural reactivity to a novel social exclusion image set: evidence from the late positive potential. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2021;51(5):916–930. doi:10.1111/sltb.12775

25. Holte AJ, Fisher WN, Ferraro FR. Afraid of social exclusion: fear of missing out predicts cyberball-induced ostracism. J Technol Behav Sci. 2022;7(3):315–324. doi:10.1007/s41347-022-00251-9

26. Thomas E, Joiner TE. Depression’s vicious scree: self-propagating and erosive processes in depression chronicity. Clin Psychol. 2000;7(2):203–218.

27. Buhle Jason T, Silvers JA, Wager TD, et al. Cognitive reappraisal of emotion: a meta-analysis of human neuroimaging studies. Cereb Cortex. 2014;24(11):2981–2990. doi:10.1093/cercor/bht154

28. Lv F, Yu M, Li J, et al. Young adults’ loneliness and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic: a moderated mediation model. Front Psychol. 2022;13:842738. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.842738

29. Sachs-Ericsson N, Carr D, Sheffler J, et al. Cognitive reappraisal and the association between depressive symptoms and perceived social support among older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2021;25(3):453–461. doi:10.1080/13607863.2019.1698516

30. Shapero BG, Stange JP, McArthur BA, Abramson LY, Alloy LB. Cognitive reappraisal attenuates the association between depressive symptoms and emotional response to stress during adolescence. Cogn Emot. 2019;33(3):524–535. doi:10.1080/02699931.2018.1462148

31. Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. doi:10.1177/014662167700100306

32. Chen Z, Yang X, Li X. Psychometric features of CES-D in Chinese adolescents. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2009;17(4):443–445.

33. Zhang D, Huang L, Dong Y. Reliability and validity of the ostracism experience scale for adolescents in Chinese adolescence. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2018;26(6):1123–1126.

34. Li X, Xin T, Yuan J, Lv L, Tao J, Liu Y. Validity and reliability of the interpersonal needs questionnaire in Chinese college students. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2015;23(4):590–593.

35. Gross JJ, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85(2):348–362. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348

36. Wang L, Liu H, Li Z, et al. Reliability and validity of emotion regulation questionnaire Chinese revised version. Chin J Health Psychol. 2007;15(6):503–505.

37. Zhang C, Wang J, Li J. Effect of college students’ social exclusion on depression: chain mediation effect of self-esteem and rumination. Chin J Health Psychol. 2022:1–10.

38. Zhou L, Geng J, Wang X, Lei L. The role of basic needs in the relationship between supervisor-induced ostracism and mental health among postgraduate students. Psychol Dev Educ. 2021;37(2):222–229.

39. Tian X, Zhang S. Social exclusion and depression: a multiple mediating model of communication anxiety and mindfulness. J Hangzhou Norm Univ (Nat Sci Ed). 2021;20(6):577–583.

40. Shen H, Li M, Li L. Influence of social exclusion on the inferiority feeling of community youth. Iran J Public Health. 2022;51(7):1576–1584. doi:10.18502/ijph.v51i7.10091

41. Chu C, Hom MA, Gallyer AJ, Hammock EAD, Joiner TE. Insomnia predicts increased perceived burdensomeness and decreased desire for emotional support following an in-laboratory social exclusion paradigm. J Affect Disord. 2019;243:432–440. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2018.09.069

42. Carrera SG, Wei M. Thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and depression among Asian Americans: a longitudinal study of interpersonal shame as a mediator and perfectionistic family discrepancy as a moderator. J Couns Psychol. 2017;64(3):280–291. doi:10.1037/cou0000199

43. Deci EL, Ryan RM. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol Inq. 2000;11(4):227–268. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

44. Grisham JR, Martyn C, Kerin F, et al. Interpersonal functioning in hoarding disorder: an examination of attachment styles and emotion regulation in response to interpersonal stress. J Obsessive Relat Disord. 2018;16:43–49. doi:10.1016/j.jocrd.2017.12.001

45. Raufelder D, Neumann N, Domin M, et al. Do belonging and social exclusion at school affect structural brain development during adolescence? Child Dev. 2021;92(6):2213–2223. doi:10.1111/cdev.13613

46. Roberts CM, Gamwell KL, Baudino MN, et al. Illness stigma, body image dissatisfaction, thwarted belongingness and depressive symptoms in youth with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;34(9):919–924. doi:10.1097/MEG.0000000000002420

47. Han J, Xiao X. Exploration and thinking of interpersonal relationship among middle school students. Course Educ Res. 2019;4:238–239.

48. Zhang Y, Luo S. The influence of class network location on adolescent mental health: the mediating role of class belonging. J Chin Youth Soc Sci. 2021;40(2):96–102.

49. Li J. Embodied Approach to Cognitive Theory of Emotion [Doctor]. Shanxi, China: Shanxi University; 2015.

50. Goldin PR, McRae K, Ramel W, Gross JJ. The neural bases of emotion regulation: reappraisal and suppression of negative emotion. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(6):577–586. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.031

51. Berking M, Poppe C, Luhmann M, Wupperman P, Jaggi V, Seifritz E. Is the association between various emotion-regulation skills and mental health mediated by the ability to modify emotions? Results from two cross-sectional studies. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2012;43(3):931–937. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.09.009

52. Wang X, Gao S, Liu S. Impact of social exclusion on college students’ internet addiction: mediation of self-concept clarity. Chin J Health Psychol. 2020;30(6):934–939.

53. Fritz HL. Why are humor styles associated with well-being, and does social competence matter? Examining relations to psychological and physical well-being, reappraisal, and social support. Pers Individ Dif. 2020;154:109641. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2019.109641

54. Meza-Cervera T, Kim-Spoon J, Bell MA. Adolescent depressive symptoms: the role of late childhood frontal EEG asymmetry, executive function, and adolescent cognitive reappraisal. Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol. 2023;51:193–207.

55. Tang H, Lyu J, Xu M. Direct and indirect effects of strength-based parenting on depression in Chinese high school students: mediation by cognitive reappraisal and expression suppression. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2022;15:3367–3378. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S390790

56. Du R, Guo L, Liang L, Zhang W. Research on the intervention of group sandplay on the psychological resilience of college students. J Campus Life Ment Health. 2020;1:62–63.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.