Back to Journals » Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment » Volume 17

The Effect of Viloxazine Extended-Release Capsules on Functional Impairments Associated with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Children and Adolescents in Four Phase 3 Placebo-Controlled Trials

Authors Nasser A, Hull JT, Liranso T, Busse GD, Melyan Z, Childress AC, Lopez FA, Rubin J

Received 20 March 2021

Accepted for publication 13 May 2021

Published 3 June 2021 Volume 2021:17 Pages 1751—1762

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S312011

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Roger Pinder

Azmi Nasser,1 Joseph T Hull,1 Tesfaye Liranso,2 Gregory D Busse,3 Zare Melyan,3 Ann C Childress,4 Frank A Lopez,5 Jonathan Rubin6

1Department of Clinical Research, Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA; 2Department of Biostatistics, Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA; 3Department of Medical Affairs, Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA; 4Center for Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine, Inc., Las Vegas, NV, USA; 5Children’s Developmental Center, Winter Park, FL, USA; 6Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA

Correspondence: Azmi Nasser

Department of Clinical Research, Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 9715 Key West Ave, Rockville, MD, 20850, USA

Email [email protected]

Purpose: The ADHD Rating Scale (ADHD-RS) assesses 18 symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity and has been used in many clinical trials to evaluate the treatment effect of drugs on ADHD. The fifth edition of this scale (ADHD-RS-5) also assesses the impact of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms on six domains of functional impairment (FI): family relationships, peer relationships, completing/returning homework, academic performance at school, controlling behavior at school, and self-esteem. Here, we report the effect of viloxazine extended-release capsules (viloxazine ER), a novel nonstimulant treatment for ADHD in children and adolescents (ages 6– 17 years), on FI from a post hoc analysis of four randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 3 clinical trials (N=1354).

Patients and Methods: ADHD-RS-5 investigator ratings of ADHD symptoms and FIs were conducted at baseline and weekly post-baseline for 6– 8 weeks in the four trials. Change from baseline (CFB) in ADHD-RS-5 FI scores (Total score [sum of 12 FI items] and Inattention and Hyperactivity/Impulsivity subscale scores [sum of 6 corresponding FI items]) and the 30% and 50% Responder Rates (ADHD-RS-5 FI Total score) were compared between viloxazine ER and placebo.

Results: The reduction (improvement) in ADHD-RS-5 FI scores (Total and subscale scores) and the percentage of responders (30% and 50%) at Week 6 were significantly greater in each viloxazine ER dose group vs placebo. In the 100– 400 mg/day viloxazine ER groups, improvements were found as early as Week 1 (100-mg/day) or Week 2 (200-, 400-mg/day) of treatment. Analysis of individual items of ADHD-related FIs demonstrated that the effect of viloxazine ER was observed across all domains of impairment.

Conclusion: Significant improvements observed in ADHD-related FIs are consistent with the reduction in inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms demonstrated in the viloxazine ER Phase 3 pediatric trials. Therefore, viloxazine ER provides clinically meaningful improvement of ADHD symptoms and functioning in children and adolescents with ADHD, starting as early as Week 1– 2 of treatment.

Keywords: impairment domains, academic performance, behavior, self-esteem

Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is the most common neurodevelopmental disorder of childhood. It is characterized by inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity symptoms and is associated with emotional dysregulation reflected in academic, social, and family impairments.1 Although multiple stimulant and nonstimulant treatment options have demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of ADHD, there is a significant proportion of individuals with ADHD who do not or only partially benefit from these medications and/or have contraindications, tolerability, or preference issues.2,3

Historically, the assessment of treatment response in individuals with ADHD has focused on measures of ADHD symptoms. However, functional impairments (FIs) across familial, social, emotional, and academic/occupational domains are frequently the reason for seeking treatment for ADHD.4 Therefore, current diagnosis of ADHD is based not only on the inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms, but also the evidence that symptoms cause functional impairments.5 The assessment and monitoring of the extent to which symptoms interfere with the quality of social, school, or work functioning of the individual is an important part of ADHD diagnosis and treatment.6

When evaluating treatment effects in individuals with ADHD, different degrees of improvement are found for symptomatic and functional outcomes. An 11-week open-label study of 200 children and adolescents with ADHD treated with extended-release methylphenidate demonstrated that only 57% of individuals showed functional improvement, even though 94% of individuals exhibited significant improvements in ADHD symptoms.7 Similar results were obtained using a reliable change index (RCI classifies individuals into three categories based on the direction and the magnitude of change [improvers, no-changers, and deteriorators] regardless of return to the normal range of functioning) in a study of children with ADHD who were enrolled in a school-based mental health program (N=64). In this study, up to 40% of children achieved reliable symptom improvement without reliable change in functioning, and up to 16% achieved reliable improvement in functioning without reliable change in symptoms.8 High numbers of individuals with incomplete ADHD symptom control and residual disabilities in cognitive functions have been reported in other population-based studies.9,10 A prospective blind longitudinal study followed up 110 children with ADHD and 105 non-ADHD controls for 10 years. While only 35% of children with ADHD met the full diagnostic criteria for ADHD in their adult years, an additional 43% had functional impairments associated with ADHD, continued to struggle with subthreshold symptoms of ADHD, or had medication-associated remission of their ADHD symptoms.11,12 These data highlighted the need for routinely including measures of functional outcomes in the assessment of treatment response.7,13

Many approaches have been used to assess impairments related to ADHD, including administering a single measure of global impairment (eg, Columbia Impairment Scale), multiple measures to assess a range of impairments such as academic performance and behavior problems, or a single measure to assess multiple domains of impairment (eg, Impairment Rating Scale or Weiss Functional Impairment Rating Scale [WFIRS]).14–16 These approaches have been frequently criticized for not assessing impairments specifically related to ADHD symptoms as opposed to other conditions, which may occur concomitantly or mimic ADHD, leading to potential problems with scale specificity.14,17

The ADHD Rating Scale (ADHD-RS) has been validated and used to assess treatment benefits of drugs in many clinical trials. It is an 18-item rating scale reflecting the 18 symptoms of ADHD based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). There are nine items that assess Inattention symptoms and nine items that assess Hyperactivity/Impulsivity symptoms.6 The earlier version of this scale (ie, ADHD-RS-IV), however, measured ADHD symptoms without assessing ADHD-related FIs. To address this unmet need in assessment of treatment response in ADHD, following the publication of DSM-5,6 the ADHD-RS has been updated. The fifth edition, ADHD-RS-5, also assesses the extent to which current ADHD symptoms affect functioning of children and adolescents across six domains of impairment.13 After completing the ratings of the nine items for each ADHD-RS-5 subscale, the clinician/investigator is asked to assess (using a 4-point Likert-scale) how much those nine items cause problems for the child/teenager in each of the six FI domains. Therefore, the ADHD-RS-5 addressed the limitations of previous measures by integrating the assessment of symptoms and impairments in the same measure, focusing on impairments specifically related to ADHD symptoms, and differentiating impairments related to each ADHD symptom dimension (Inattention and Hyperactivity/Impulsivity).14

Viloxazine extended-release capsules (viloxazine ER; QelbreeTM) is a novel nonstimulant medication which has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of ADHD in children and adolescents (ages 6–17 years). The objective of this post hoc analysis was to evaluate the effect of viloxazine ER on ADHD-RS-5 derived FI scores assessed in children and adolescents with ADHD during four Phase 3 clinical trials (the primary data from these clinical trials have been reported elsewhere).18–21

Methods

Phase 3 Trials Providing Data

The ADHD-RS-5 data collected during four Phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, 3-arm clinical trials of viloxazine ER in children and adolescents (6–17 years of age) with ADHD were integrated in this analysis (Table 1).18–21 ADHD-RS-5, Home Version: Child (6–11 years of age) or ADHD-RS-5, Home Version: Adolescent (12–17 years of age) was administered at each study visit.

|

Table 1 Overview of Phase 3 Randomized Controlled Trials Providing Data |

In each study, the parent(s) or legal guardian(s) of each subject provided written informed consent to allow their child’s participation prior to any study-related procedures. Assent was also obtained from the subject, if applicable, according to local requirements. The study protocols were approved by Advarra Institutional Review Board (IRB) and conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and the International Council for Harmonisation Note for Guidance on Good Clinical Practice. All versions of the informed consent form were reviewed and approved by IRB.

Eligibility in these studies was determined using predefined inclusion/exclusion criteria.18–21 Subjects with a diagnosis of ADHD based on DSM-56 criteria and confirmed by the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-KID), ADHD-RS-5 Total score of ≥28, and Clinical Global Impression-Severity of Illness (CGI-S)22 scale score of ≥4 were eligible to participate. Key exclusion criteria were as follows: major psychiatric disorder or neurological disorder (excluding oppositional defiant disorder, or major depressive disorder if the individual was free of major depressive episodes within the 6 months prior to screening), a history of allergic reaction to viloxazine or its excipients, any food allergy/intolerance that contraindicated trial participation, suicidal ideation, history of seizures, or significant systemic disease. Subjects had to weigh ≥20 kg (children) or ≥35 kg (adolescents) and have a body mass index ≤95th percentile for the appropriate age and gender.

After a screening period (≤28 days), eligible subjects were randomized (1:1:1 ratio) to receive one of the two viloxazine ER doses or placebo (the treatment groups, treatment duration, and titration periods are summarized in Table 1).18–21 Subjects were instructed to take the study medication once daily by mouth in the morning, with or without food, throughout the treatment period. The viloxazine ER and placebo capsules were identical in appearance. If necessary, the subject’s parent(s) or legal guardian(s) could open the capsules and sprinkle the contents over a spoon of soft food (eg, apple sauce). Subjects were required to refrain from taking medications prohibited by the study protocol, including FDA-approved ADHD medications, starting at least 1 week prior to randomization until the end of study. Baseline ADHD-RS-5 and safety assessments were conducted on the day, but prior to, randomization and the administration of the first dose of study medication. They were then repeated weekly during post-baseline study visits until the end of study or early termination.18–21 The ADHD-RS-5 was administered by a trained clinician/investigator.

ADHD-RS-5 FI Analysis

After completing the ratings of the nine items for each ADHD-RS-5 subscale, the clinician/investigator rated the child/teenager on a 4-point Likert-scale (0–3; where 0=No Problem; 1=Minor Problem; 2=Moderate Problem; 3=Severe Problem) on “How much do the nine behaviors in the previous question cause problems for the child/teenager?” in the following six FI domains:

- Getting along with family members

- Getting along with other children/teenagers

- Completing or returning homework

- Performing academically in school

- Controlling behavior at school

- Feeling good about himself/herself

The change from baseline (CFB) in the ADHD-RS-5 FI scores by study visit (Total and for the Inattention and Hyperactivity/Impulsivity subscales) and the 30% and 50% Responder Rates were evaluated. The ADHD-RS-5 Inattention FI score was the sum of six impairment items assessed for the Inattention subscale. The ADHD-RS-5 Hyperactivity/Impulsivity FI score was the sum of six impairment items for the Hyperactivity/Impulsivity subscale. The ADHD-RS-5 Total FI score was the sum of all 12 impairment items. The 30% and 50% Responder Rates represent proportions of subjects who achieved 30% or 50% improvement in the ADHD-RS-5 Total FI score. The 30% response threshold was selected as it is among the most commonly cited thresholds in ADHD studies,23–25 while the 50% response threshold was selected as it has been shown to be statistically linked with the Clinical Global Impression-Improvement (CGI-I) score of 2 (much improved),26,27 commonly used as the minimum threshold for clinically meaningful change.28,29

The data were analyzed using mixed model for repeated measures (MMRM), which included fixed effect terms for baseline, age group, treatment (dose 100-mg/day, 200-mg/day, 400-mg/day, and 600-mg/day), visit, and treatment-by-visit interaction as independent variables. The least square (LS) means ± standard error (SE) compared to placebo and p values were determined for all measures. Data from four trials over 6 weeks of treatment with viloxazine ER were analyzed and presented by dose (100-mg/day, 200-mg/day, 400-mg/day, and 600-mg/day). The 30% and 50% Responder Rates were analyzed using the Pearson’s Chi-square test. Numbers needed to treat (NNT) were calculated based on 30% and 50% Responder Rates. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS® system software, version 9.2 or higher.

Results

A total of 1354 subjects with ADHD (intent-to-treat population) were included in the four Phase 3 trials of viloxazine ER (subjects treated with placebo: 452; subjects treated with 100-mg/day viloxazine ER: 147; subjects treated with 200-mg/day viloxazine ER: 359; subjects treated with 400-mg/day viloxazine ER: 299; and subjects treated with 600-mg/day viloxazine ER: 97). Of these subjects, 761 were children 6–11 years of age and 593 were adolescents 12–17 years of age; a majority were male (n=873) and either White (n=759) or African American (n=529). Seven subjects (five from the placebo group and two from the 200-mg/day viloxazine ER group) were excluded from the current analysis because they had no impairment item data at baseline.

CFB ADHD-RS-5 FI Score

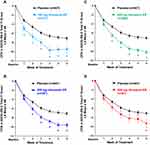

Statistically significant improvement vs placebo was observed in the CFB ADHD-RS-5 Total FI scores: with 100-mg/day viloxazine ER, starting at Week 1 of treatment (p=0.0041) through Week 6 (p=0.0026); with 200- or 400-mg/day viloxazine ER starting at Week 2 of treatment (p=0.0018 and p=0.0003, respectively) through Week 6 (p<0.0001 and p<0.0001, respectively); and with 600-mg/day viloxazine ER, at Week 6 (p=0.0208) (Figure 1).

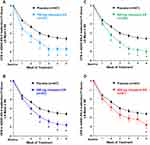

Statistically significant improvement vs placebo was observed in the CFB ADHD-RS-5 Inattention FI scores: with 100-mg/day viloxazine ER, starting at Week 1 of treatment (p=0.0040) through Week 6 (p=0.0085); with 200- or 400-mg/day viloxazine ER, starting at Week 2 of treatment (p=0.0088 and p=0.0020, respectively) through Week 6 (p<0.0001 and p<0.0001), and with 600-mg/day viloxazine ER, at Week 6 (p=0.0183) (Figure 2).

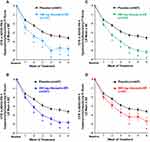

Statistically significant improvement vs placebo was observed in the CFB ADHD-RS-5 Hyperactivity/Impulsivity FI scores: with 100-mg/day viloxazine ER, starting at Week 1 of treatment (p=0.0187) through Week 6 (p=0.0020); with 200- or 400-mg/day viloxazine ER, starting at Week 2 of treatment (p=0.0012 and p=0.0001, respectively), through Week 6 (p<0.0001 and p<0.0001); and with 600-mg/day viloxazine ER, at Week 4 (p=0.0428) and Week 6 (p=0.0208) (Figure 3).

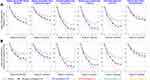

CFB ADHD-RS-5 scores for each Inattention and Hyperactivity/Impulsivity FI item by week of treatment and by dose are shown in Figure 4. These descriptive statistics curves demonstrate that, overall, the effect of viloxazine ER was observed across all FI items for both the Inattention and Hyperactivity/Impulsivity subscales.

30% and 50% Responders for ADHD-RS-5 Total FI Score

A significantly higher percentage of viloxazine ER treated subjects achieved a ≥30% reduction (improvement) in the CFB ADHD-RS-5 Total FI score (30% Responders) compared to placebo-treated subjects at Week 1, 4, 5, and 6 with 100-mg/day viloxazine ER; Weeks 2 through 6 with 200- or 400-mg/day viloxazine ER; and at Week 3, 4, and 6 with 600-mg/day viloxazine ER (Table 2).

|

Table 2 30% Responder Rate Based on ADHD-RS-5-Derived Total Functional Impairment Score by Week |

The 30% Responder Rate at Week 6 was as follows: 53.4% for placebo; 64.0% for 100-mg/day viloxazine ER (p=0.0293); 65.1% for 200-mg/day viloxazine ER (p=0.0015); 74.3% for 400-mg/day viloxazine ER (p<0.0001); and 70.4% for 600-mg/day viloxazine ER (p=0.0049) (Table 2). The NNTs for 100-, 200-, 400-, and 600-mg/day, based on 30% Responder Rates at Week 6, were 9.4, 8.6, 4.8, and 5.9, respectively.

A significantly higher percentage of viloxazine ER treated subjects achieved a ≥50% reduction (improvement) in the CFB ADHD-RS-5 Total FI score (50% Responders) compared to placebo-treated subjects at Week 1, 3, 4, 5, and 6 with 100-mg/day viloxazine ER; Weeks 2 through 6 with either 200- or 400-mg/day viloxazine ER; and Week 2, 3, 4, and 6 with 600-mg/day viloxazine ER (Table 3).

|

Table 3 50% Responder Rate Based on ADHD-RS-5-Derived Total Functional Impairment Score by Week |

The 50% Responder Rate at Week 6 was as follows: 37.8% for placebo; 53.2% for 100-mg/day viloxazine ER (p=0.0014); 50.3% for 200-mg/day viloxazine ER (p=0.0007); 56.2% for 400-mg/day viloxazine ER (p<0.0001); and 53.1% for 600-mg/day viloxazine ER (p=0.0104) (Table 3). The NNTs for 100-, 200-, 400-, and 600-mg/day, based on 50% Responder Rates at Week 6, were 6.5, 8, 5.4, and 6.5, respectively.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate a change in the ADHD-RS-5 impairment scores following a treatment with an approved or investigational medication for ADHD using a large sample of children and adolescents. The larger sample size was achieved by pooling data from multiple studies, which increased the statistical power of the analysis and allowed for integrated evaluation of each dose group across the studies. This analysis has demonstrated significant improvements in the CFB ADHD-RS-5 Total, Inattention, and Hyperactivity/Impulsivity FI scores compared to placebo. The analysis of CFB ADHD-RS-5 scores (Figures 1–3) by week found that with 100- to 400-mg/day viloxazine ER, the separation from placebo started at Week 1–2 of treatment. With 600-mg/day viloxazine ER, the statistically significant improvements vs placebo for Total and Inattention FI scores were only observed at Week 6 and for Hyperactivity/Impulsivity FI scores at Week 4 and Week 6. The responder analysis demonstrated that at Week 6, 50% to 56% of subjects treated with 100- to 600-mg/day viloxazine ER had 50% improvement in FI (Table 3), while 64% to 74% of subjects displayed a 30% improvement in FI at the same time point (Table 2). The NNTs for most of the dose groups at Week 6 were around 5 and 6 (ranging from 4.8 to 9.4), which is consistent with the effect sizes evaluated based on the primary data reported for viloxazine ER.30

These results are consistent with the primary data of viloxazine ER, which have demonstrated statistically significant improvements in ADHD symptoms vs placebo for 100-, 200-, and 400-mg/day viloxazine ER (as measured with ADHD-RS-5 and CGI-I scales) across three of four pivotal trials.18–20 In the fourth clinical trial, the primary efficacy endpoint was not achieved; one of the active arms (400-mg/day) separated from placebo but the other active arm (600-mg/day) did not. Thus, the trial was considered negative due to step-down statistical analysis.21 The placebo response in the fourth study was higher than in the three other studies and may have contributed to the 600-mg/day dose failure.21

Interestingly, a statistically significant increase in the 50% Responder Rate for ADHD-RS-5 Total FI score was demonstrated between all doses of viloxazine ER (including 600-mg/day) compared to placebo at nearly every weekly post-baseline assessment from Week 1 (100-mg/day) or 2 (200-, 400-, and 600-mg/day) through Week 6 (shaded cells in Table 3). The 30% Responder Rate results showed a similar pattern, except an increase with 600-mg/day viloxazine ER was not observed until Week 3 (shaded cells in Table 2). In the primary analysis of the Phase 3 trials, the 50% Responder Rate for the ADHD-RS-5 symptoms was also increased for all doses of viloxazine ER, but the difference vs placebo for 600-mg/day of viloxazine ER was not statistically significant.

In the clinical trials of viloxazine ER, changes in subjects’ functioning were also evaluated by parents using WFIRS–Parent (WFIRS–P). Similar to the ADHD-RS-5 FI items, which assess to what degree ADHD symptoms affect an individual’s ability to accomplish daily tasks and interactions, the WFIRS–P assesses to what degree an individual’s behavior and emotional problems affect their ability to accomplish daily tasks and interactions (without taking into account the ADHD symptoms).15,31 The 50 items included in this scale are grouped into six domains (family, school, life skills, self-concept, social activities, and risky activities) that are scored using a 4-point Likert scale.

While none of the viloxazine ER Phase 3 trials were powered to detect changes vs placebo in CFB at end of study using the WFIRS–P, the Phase 3 trial with the highest sample size (Table 1) that evaluated 100- and 200-mg/day viloxazine ER vs placebo was able to detect a statistically significant improvement in the WFIRS–P Total average score.18 Statistically significant improvements were also observed in several individual WFIRS–P domains in the three studies (evaluating 100- and 200-mg/day viloxazine ER vs placebo in children and 200- and 400-mg/day viloxazine ER vs placebo in children and adolescents), including the domains of family, school, social activities, and risky activities.18–20 Therefore, WFIRS–P data support findings presented in the current study. Multi-informant assessment in ADHD has been suggested as an important approach to comprehensive evaluation of individual’s functional outcomes.14 Therefore, the use of two types of assessments provided by different informants (ie, clinicians and parents) for viloxazine ER can provide a more comprehensive understanding of how much the individual’s functionality improves in response to treatment in different domains of the individual’s life.

The descriptive statistics in the present post hoc analysis revealed improvements in both ADHD-RS-5 Inattention and Hyperactivity/Impulsivity FI scores across all impairment domains with all doses of viloxazine ER (100- to 600-mg/day), with somewhat greater effects seen in the academic performance and behavioral functioning at school and at home, followed by family and peer relationship domains, and a relatively smaller effect seen in the self-esteem domain (Figure 4, solid lines). Interestingly, the individual dose curves showed that while the improvements in all FI domains reached a plateau at approximately Week 3 with 100-mg/day dose of viloxazine ER, there was still a trend for improvement after Week 3 with higher doses (Figure 4, dotted lines).

One of the potential limitations of this study is that the data collected here were based on investigator-rated scales, and no parent or teacher ratings were included in this analysis. Parent-rated scales were used in individual trials of viloxazine ER and are described in their respective publications.18–21 Another potential limitation is the length of follow-up. In the future, studies with longer duration may provide further insights into functional outcomes with viloxazine ER treatment. Finally, the current findings cannot be directly compared to those for other medications, given the differences in how response rates are reported across studies.

To summarize, the statistically significant improvements vs placebo in the CFB ADHD-RS-5 FI scores and 30% and 50% Responder Rates observed in this post hoc analysis extend the primary efficacy data reported in the Phase 3 clinical trials of viloxazine ER demonstrating early and sustained improvement in inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms. Furthermore, a recently published analysis using a machine learning approach has demonstrated that early response to viloxazine ER treatment at Week 2 can be predictive of efficacy outcome at Week 6.32 Together, these results demonstrate that viloxazine ER (viloxazine extended-release capsules) can be considered an effective and well-tolerated treatment option that provides clinically meaningful improvement in ADHD symptoms and functioning in children and adolescents starting as early as Week 1–2 of treatment.

Funding

The study was funded by Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Disclosure

AN, JTH, TL, GDB, ZM, and JR are employees of Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc. FAL has served as a consultant to and received speaker fees and/or research support from Eli Lilly, GSK, Ironshore, Neos, Novartis, Noven, Pfizer, Shire, Sunovion, Supernus, and Tris. ACC has served as a consultant, participated in advisory board meetings and received speaker fees and/or research support from Allergan, Takeda (Shire), Emalex, Akili, Arbor, Cingulate, Ironshore, Aevi Genomic Medicine, Neos, Otsuka, Pfizer, Purdue, Adlon, Rhodes, Sunovion, Tris, KemPharm, Supernus, US FDA, Corium, Jazz, Tulex Pharma, and Receptor. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Mattingly GW, Anderson RH. Optimizing outcomes in ADHD treatment: from clinical targets to novel delivery systems. CNS Spectr. 2016;21(S1):45–59. doi:10.1017/S1092852916000808

2. Childress A, Tran C. Current investigational drugs for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2016;25(4):463–474. doi:10.1517/13543784.2016.1147558

3. Cutler AJ, Mattingly GW, Jain R, O’Neal W. Current and future nonstimulants in the treatment of pediatric ADHD: monoamine reuptake inhibitors, receptor modulators, and multimodal agents. CNS Spectr. 2020;1–27. doi:10.1017/S1092852920001984

4. Epstein JN, Weiss MD. Assessing treatment outcomes in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a narrative review. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2012;14(6). doi:10.4088/PCC.11r01336

5. Faraone SV, Asherson P, Banaschewski T, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15020.

6. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th Ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

7. Weiss M, Childress A, Mattingly G, Nordbrock E, Kupper RJ, Adjei AL. Relationship between symptomatic and functional improvement and remission in a treatment response to stimulant trial. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2018;28(8):521–529. doi:10.1089/cap.2017.0166

8. Owens J, Johannes LM, Karpenko V. The relation between change in symptoms and functioning in children with ADHD receiving school-based mental health services. School Ment Health. 2009;1:183–195. doi:10.1007/s12310-009-9020-y

9. Hodgkins P, Setyawan J, Mitra D, et al. Management of ADHD in children across Europe: patient demographics, physician characteristics and treatment patterns. Eur J Pediatr. 2013;172(7):895–906. doi:10.1007/s00431-013-1969-8

10. Sikirica V, Flood E, Dietrich CN, et al. Unmet needs associated with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in eight European countries as reported by caregivers and adolescents: results from qualitative research. Patient. 2015;8(3):269–281. doi:10.1007/s40271-014-0083-y

11. Biederman J, Petty CR, Evans M, Small J, Faraone SV. How persistent is ADHD? A controlled 10-year follow-up study of boys with ADHD. Psychiatry Res. 2010;177(3):299–304. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2009.12.010

12. Uchida M, Spencer TJ, Faraone SV, Biederman J. Adult outcome of ADHD: an overview of results from the MGH longitudinal family studies of pediatrically and psychiatrically referred youth with and without ADHD of both sexes. J Atten Disord. 2018;22(6):523–534. doi:10.1177/1087054715604360

13. DuPaul GJ, Power TJ, Anastopoulos AD, et al. ADHD Rating Scale-5 for Children and Adolescents: Checklists, Norms, and Clinical Interpretation. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2016.

14. Power TJ, Watkins MW, Anastopoulos AD, Reid R, Lambert MC, DuPaul GJ. Multi-informant assessment of ADHD symptom-related impairments among children and adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2017;46(5):661–674. doi:10.1080/15374416.2015.1079781

15. Gajria K, Kosinski M, Sikirica V, et al. Psychometric validation of the Weiss Functional Impairment Rating Scale-Parent Report Form in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:184. doi:10.1186/s12955-015-0379-1

16. Fabiano GA, Pelham WE, Waschbusch DA, et al. A practical measure of impairment: psychometric properties of the impairment rating scale in samples of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and two school-based samples. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2006;35(3):369–385. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3503_3

17. Vazquez AL, Sibley MH, Campez M. Measuring impairment when diagnosing adolescent ADHD: differentiating problems due to ADHD versus other sources. Psychiatry Res. 2018;264:407–411. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2018.03.083

18. Nasser A, Liranso T, Adewole T, et al. A phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled trial to assess the efficacy and safety of once-daily SPN-812 (viloxazine extended-release) in the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in school-age children. Clin Ther. 2020;42(8):1452–1466. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2020.05.021

19. Nasser A, Liranso T, Adewole T, et al. A phase 3, placebo-controlled trial of once-daily viloxazine extended-release in adolescents with ADHD. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2021;In press.

20. Nasser A, Liranso T, Adewole T, et al. Once-Daily SPN-812 200 and 400 mg in the treatment of ADHD in school-aged children: a phase III randomized, controlled trial. Clin Ther. 2021. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2021.01.027

21. Nasser A, Liranso T, Adewole T, et al. A phase 3 placebo-controlled trial of once-daily 400-mg and 600-mg SPN-812 (viloxazine extended-release) in adolescents with ADHD. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2021;51(2):43–64.

22. Guy W. Clinical Global Impression (CGI). Early Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit (ECDEU) Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration; National Institute of Mental Health; Psychopharmacology Research Branch; Division of Extramural Research Programs; 1976:218–222.

23. Michelson D, Allen AJ, Busner J, et al. Once-daily atomoxetine treatment for children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(11):1896–1901. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.11.1896

24. Kemner JE, Starr HL, Ciccone PE, Hooper-Wood CG, Crockett RS. Outcomes of OROS methylphenidate compared with atomoxetine in children with ADHD: a multicenter, randomized prospective study. Adv Ther. 2005;22(5):498–512. doi:10.1007/BF02849870

25. Spencer T, Biederman J, Wilens T, et al. Efficacy of a mixed amphetamine salts compound in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(8):775–782. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.775

26. Goodman D, Faraone SV, Adler LA, et al. Interpreting ADHD rating scale scores: linking ADHD rating scale scores and CGI levels in two randomized controlled trials of lisdexamfetamine dimesylate in ADHD. Prim Psychiatry. 2010;17(3):44–52.

27. Nasser A, Kosheleff AR, Hull JT, et al. Translating ADHD-RS-5 and WFIRS-P effectiveness scores into CGI clinical significance levels in four randomized clinical trials of SPN-812 (viloxazine extended-release) in children and adolescents with ADHD. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2021;31:214–226. doi:10.1089/cap.2020.0148

28. Busner J, Targum SD. The clinical global impressions scale: applying a research tool in clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2007;4(7):28–37.

29. Kay SR. Positive-negative symptom assessment in schizophrenia: psychometric issues and scale comparison. Psychiatr Q. 1990;61(3):163–178. doi:10.1007/BF01064966

30. Nasser A, Kosheleff AR, Hull JT, et al. Evaluating the likelihood to be helped or harmed after treatment with viloxazine extended-release in children and adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;In press.

31. Thompson T, Lloyd A, Joseph A, Weiss M. The Weiss Functional Impairment Rating Scale-Parent Form for assessing ADHD: evaluating diagnostic accuracy and determining optimal thresholds using ROC analysis. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(7):1879–1885. doi:10.1007/s11136-017-1514-8

32. Faraone SV, Gomeni R, Hull JT, et al. Early response to SPN-812 (viloxazine extended-release) can predict efficacy outcome in pediatric subjects with ADHD: a machine learning post-hoc analysis of four randomized clinical trials. Psychiatry Res. 2021;296:113664. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113664

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.