Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

The Effect of Loneliness on Non-Suicidal Self-Injury Behavior in Chinese Junior High School Adolescents: A Moderated Mediation Model

Authors Huang X, Liu H, Lan Z , Deng F

Received 9 March 2023

Accepted for publication 8 May 2023

Published 16 May 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 1831—1843

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S410535

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Xuefang Huang,1 Huaqiang Liu,2 Zhensong Lan,3 Fafang Deng3

1School of Teacher Education, Hechi University, Yizhou, 546300, People’s Republic of China; 2School of Law and Public Administration, Yibin University, Yibin, 644000, People’s Republic of China; 3School of Public Administrations, Hechi University, Yizhou, 546300, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Huaqiang Liu, Yibin University, 8 Jiusheng Road, Cuiping District, Yibin, Sichuan, 644000, People’s Republic of China, Tel +86 13060000980, Email [email protected]

Purpose: This study explore the interaction between loneliness and non-suicidal self-injury behaviors (hereinafter “NSSI”), and to further examine the mediating role of self-control and the moderating role of social connection.

Methods: A total of 414 junior high school students (age 14.05± 0.84) in Sichuan province in China were investigated on their loneliness, self-control, social connection and NSSI by questionnaire.

Results: (1) there was a significant positive correlation between loneliness and NSSI; (2) self-control played a mediating role in the relationship between loneliness and NSSI; and (3) after controlling for gender, family structure, and family economic level, the social connectedness played a moderating role in the relationship between loneliness and NSSI, as well as between self-control and NSSI.

Conclusion: The results verify the relationship between loneliness and NSSI, expands and deepens the internal logical relationship between them, and provides a reference that can be used in the future for the prevention and intervention of NSSI in adolescents.

Keywords: adolescents, loneliness, non-suicidal self-injury behavior, NSSI, self-control, social connection, high school students

Introduction

A complex relationship exists between NSSI and suicide, which makes it a prominent public health problem as it seriously endangers the daily life as well as the physical and mental health of adolescents.1 Studies exhibit that the incidence of NSSI behavior is relatively high among Chinese adolescents.2 Simultaneously, adolescence is additionally a period of high incidences of loneliness among adolescents. A cross-sectional study from England found that 18.1% of adolescents aged 12–18 reported having felt lonely “often”3 Loneliness is an unpleasant and distressing subjective experience or psychological feeling.4,5 During a lonely state, individuals not only exhibit the subjective state of social isolation, but additionally go through the painful experience of non-acceptance caused by their perception of isolation or lack of contact with others.6 Adolescents’ experience of loneliness has an important impact on cognition, emotion and behavior.7 It has been found that as loneliness intensifies, individual NSSI may increase.8–10 Individuals who experience being lonely often are more likely to report suicidal thoughts and behaviors than their peers.11,12 Therefore, it is of great practical significance for junior high school adolescents to pay more attention to their state of loneliness and understand the covariant relationship between loneliness and NSSI, so as to reduce NSSI in the future.

Loneliness and NSSI

Loneliness can be described as a subjective sense of isolation in relation to social interaction, or a painful experience caused by the perception of isolation or lack of contact with others.6 Palmer divides loneliness into long-term loneliness (chronic loneliness) and short-term loneliness, where long-term loneliness is mostly innate.13 While self-isolation may have some positive consequences, such as deepening self-understanding, it appears to be based on individual experiences of pain and harm. Among those who experience distress, loneliness is associated with increased self-reported thoughts of NSSI and failure.12 The interpersonal theory of suicide states that loneliness contributes to the emergence of frustration with a combination of a perceived burden – as a result, this triggers the desire to die and the probability of NSSI is higher.12 Relationship problems (such as peer and family relationships) have been reported as a major risk factor for NSSI in children and adolescents;14 however, not all studies have demonstrated a link between loneliness and NSSI.11,12 The theory of suicidal behavior,15–17 suggests that social relationships or longing thereof play a key role in suicidal behavior. In light of this theory, adolescents may suffer from loneliness as a result of the lack or isolation of social relations, as well as increased severe distress, which may increase adolescents’ NSSI. Based on the above, a close relationship between loneliness and NSSI exists. This study therefore proposes

Hypothesis 1: there is a positive correlation between adolescent loneliness and NSSI.

Loneliness, Self-Control and NSSI

Self-control is the ability of an individual to resist immediate temptation or endure immediate pain and unhappiness for the sake of an ideal long-term goal;18–20 or take themselves as the subject, formulate certain standards or norms according to the needs of the situation and the intention of the subject, and then carry out or stop, insist or give up the behavior affecting the subject positively or negatively.21 A more positive definition of self-control is that individuals autonomously regulate their behavior to match their personal values and social expectations.22–24 As a result, on the one hand, self-control refers to inhibition or control, that is, the ability to regulate one’s emotions, thoughts, and behavior in the face of temptations and impulses; on the other, it is also manifested as an executive function, which is a cognitive process that is necessary to regulate one’s behavior in order to achieve specific goals.

The self-control theory exhibits that a lack of self-control is the main cause of all violent and risk-taking behaviors25 that are related to most behavioral problems.26 A lack of self-control is characterized by behaviors that include impulsivity, risk-taking, addiction, and preference for physical rather than mental activity.27 Individuals with high self-control are less likely to be affected by stressful events28 and more tolerant of painful stimuli29 as opposed to individuals who lack self-control.30 High levels of self-control are characterized by thinking about long-term outcomes rather than immediate gratification, and such attitudes are accompanied by better interpersonal relationships, better psychological adjustment, the ability to cope with negative thoughts, and the ability to control individual behavior.24,31,32

It has been preliminarily proved that children and adolescents’ psychological problems (such as loneliness and depression) are negatively related to self-control.26,27,33 As a result of low self-control negative emotions such as loneliness and depression are related to negative outcomes. Individuals who lack self-control may have difficulties in controlling emotions and behaviors, and tend to exhibit stronger impulses, which makes them more likely to produce negative outcomes such as NSSI.34 A lack of self-control is associated with higher loneliness, which leads to peer rejection and active or passive solitude, resulting in a decline in self-control.20,35 In the specific context of China, adolescents with strong self-control are often considered to be more socially competent, which in turn may improve peer relationships as well as bring about a sense of security and belonging.36 Therefore, it is of positive significance to explore the role of individual self-control in the relationship between loneliness and NSSI in order to prevent and intervene adolescents’ NSSI.

Hypothesis 2: Self-control plays a mediating role between loneliness and NSSI.

Loneliness, Self-Control, Social Connection and NSSI

Based on the definition of loneliness, individuals may feel lonely as a result of minimal social interaction or increased isolation from others.37 Social connection refers to an individual’s subjective perception of the closeness of their interpersonal relationships in social life.38 It has been found that men living with a partner appear to be associated with a reduced risk of death by suicide as well as hospitalization for NSSI.39 Some scholars have proposed that negative emotional states can motivate individuals to make use of online interactions to regulate their emotions.40,41 This means that when people feel lonely, they are more inclined to regulate their emotions through various forms of social interaction, as a result reducing negative emotions and loneliness. In addition, loneliness has also been found to be associated with cognitive biases that are negative in social interactions.42

The evolutionary theory suggests that loneliness may operate through a social distress mechanism that motivates people to repair and maintain social bonds.43,44 In the theoretical perspective of suicidal behavior, social relations and a sense of belonging play a key role in suicidal behavior.15–17 The interpersonal function theory suggests that because NSSI has positive social functions, such as gaining support or increasing contact with others, the experience of social distress may lead individuals to NSSI.45–47 Social support is an important element in an individual’s interpersonal relationship. The main effect model of social support also states that the social support obtained by individuals has a direct impact on their mental health, regardless of whether they are experiencing stress or not, and good social support has a positive effect on maintaining a positive emotional experience.48 In consideration, adolescents’ peers and friends are key sources of support for their mental health problems and NSSI.3,49 When adolescents’ social support networks are disrupted, additional risk factors may increase their NSSI and suicidal behavior.47 In contrast, positive social relationships and social connection may assist them in reducing these behaviors.50

Social support can improve individuals’ self-esteem and trust, as well as make individuals more psychologically healthy and happy,44,51 while establishing positive relationships with others can effectively reduce loneliness and increase self-confidence and a sense of belonging. However, individuals who feel lonely are more likely to feel powerless and anxious in interpersonal relationships and spend less time on social activities, which further weakens social ties and makes it difficult to maintain stable interpersonal relationships.52 Similarly, for individuals with accumulated negative emotions and impaired social functions, they are often unwilling to take the initiative to communicate with others and lack the ability to establish friendly relationships with others, which is the main cause of loneliness and the obstacle to eliminating loneliness.53 Long-term self-isolation and isolation from others can lead to severe depression and loneliness, which can alleviate inner pain by hurting the body.50,54,55 Therefore, the acquisition of social skills for interpersonal communication to enhance social connection and improve social support may become an important way to reduce loneliness.

Social connectedness can promote the development of self-control.56 Loneliness tends to make individuals have low social connectedness, when individuals find it difficult to control their own needs and feelings.57 Simultaneously, their cognition is more negative, they lack a good social support system, and find it difficult to actively participate in social interaction.58 Low self-control, which is associated with negative interpersonal outcomes, may lead to peer rejection and thus loneliness, which has important implications for interpersonal relationships.24 Some scholars have proposed that long-term loneliness and poor social skills are related to negative peer interaction. Children who are more likely to be accepted by their peers and have more opportunities for social interaction are less likely to experience loneliness as opposed to children who lack social connections.24,52,59 This means that there is a correlation between self-control and social connection, as social connections stimulated by loneliness provides the possibility for individuals to develop self-control.36

In summary, there seems to be a link between social connectedness and loneliness, self-control, as well as NSSI. This study intends to further examine the role of social connection on loneliness, self-control and NSSI, in order to explore whether strengthening social connection can alleviate loneliness, or improve the level of individual self-control, thereby reducing the possibility of NSSI and suicide. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed in this study:

3A: Social connectedness moderates the relationship between loneliness and self-control; 3B: Social connectedness moderates the relationship between loneliness and NSSI; 3C: Social connectedness moderates the relationship between self-control and NSSI.

Research Methods

Participants

The subjects of this study are mainly adolescents in junior high school - around the world, this usually refers to junior high school students in grades 7–9 (age 14.05±0.84). Before conducting the survey, all participants were informed about the contents of the survey and obtained their consent, as well as the informed consent of the participants’ parents or legal guardians and the class teacher. The survey lasted about 1 hour, and questionnaires were handed out and collected by the researchers on site. This study was reviewed and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Yibin University, China (No. 2022-04-21-01Y).

The study makes use of the cluster stratified sampling method, where two junior middle schools were randomly selected from Luzhou City, China. From each of the two schools, one class was then randomly selected from three grades, and finally all the students in the six classes were surveyed through a questionnaire. After deleting the invalid questionnaires, 414 valid participants were obtained. Of these, 239 were boys and 175 were girls; there were 109 students in the seventh grade, 145 in the eighth grade and 160 in the ninth grade. In terms of family structure, most participants lived with grandparents and/or parents (80.7%), single-parent families (3.4%), reorganized families (1.9%) and other types (14%); In terms of household economic status, the majority of households were in the average level (79.5%), followed by those in the bi level (10.6%) and those in the low level (1.7%). In this study, 32.9% of the participants had experienced NSSI behavior. But in the last month, the incidence of NSSI behavior among participants was 14.7%. The main ways of self-injury were hitting hard objects with fists (16.7%), intentionally strangling (15.9%), or intentionally scratching (12.6%). See Table 1 for the above information.

|

Table 1 Demographics |

Measuring Tools

Loneliness Scale

The Adolescent Loneliness Scale (revised by Zou) was used to measure the level of loneliness experienced by the adolescents60. The scale consists of 21 items, including pure loneliness, perceived social competence, peer relationship evaluation, and perceived satisfaction with important relationships. Participants were asked to rate the description of each item, for example, “I have no one to talk to in class”. A 5-point Likert scale was made use of and each item was scored by assigned rules such as “1 = never, 2 = occasionally, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often, and 5 = always”, which were finally converted by reverse scoring. The higher the score, the stronger the loneliness of the individual. In this study, the Cronbach’s α of the scale was 0.93, and the test value of the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (hereinafter “KMO” and Bartlett’s was 0.94.

Self-Control Scale

The self-control scale revised by Hu et al61 was used to measure the degree of self-control that the adolescents had. The scale consists of 19 items, which were divided into five dimensions, namely: impulse control, healthy habits, resisting temptation, focusing on school work (ie, studying) and abstinence from entertainment. The participants were asked to rate the description of each item, for example, “I can resist temptation very well”. A 5-point Likert scale was made use of and each item was scored by assigned rules such as “1 = never, 2 = occasionally, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often, and 5 = always”, which were finally converted by reverse scoring. The higher the score, the lower the individual’s ability to exercise self-control. In this study, the Cronbach’s α of the scale was 0.91, and the KMO and Bartlett’s test value was 0.93.

Social Association Scale

The social connection scale revised by Fan et al62 was used as a measurement tool to measure the degree of social connection that the adolescents had. The scale consisted of 20 items, which were divided into three dimensions, namely: the sense of integration, the sense of acceptance and the involvement in life. Participants were asked to rate the description of each item, for example, “I feel isolated from the world around me”. A 5-point Likert scale was made use of and each item was scored by assigned rules such as “1 = never, 2 = occasionally, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often, and 5 = always”, which were finally converted by reverse scoring. The higher the score, the worse the social connection of the individual. In this study, the Cronbach’s α of the scale was 0.92, and the KMO and Bartlett’s test value was 0.94.

Ottawa Non-Suicidal Self-Injury Behavior Questionnaire

The Ottawa non-suicidal self-injury behavior questionnaire (Chinese version), revised and tested by Zhang et al63 was used. In this study, four dimensions were selected, including the individual’s way of NSSI, the frequency of occurrence, the cause of occurrence, and the consequences of NSSI. The participants were asked to rate the description of each item, such as whether they had “deliberately pinched themselves”, “the frequency of their non-suicidal self-injury behavior in the past month”, “expressed their anger” and “caused themselves to give up or reduce important social activities”. A 5-point Likert scale was made use of and each item was scored by assigned rules such as “1 = completely non-conforming, 2 = relatively non-conforming, 3 = general, 4 = relatively conforming, and 5 = completely conforming”. In this study, the Cronbach’s α of the scale was 0.98, and the test value of the KMO and Bartlett’s test was 0.96.

Analysis Method

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (hereinafter “SPSS”) 23.0 and the Analysis of Moment Structures (hereinafter “AMOS”) 24.0 were used for the descriptive statistical analysis, bivariate correlation analysis and other data analysis; while the Hayes Process plug-in64 was used for the Bootstrap path effect analysis and the moderating effect analysis.

Result

Common Method Bias Test

Harman’s single-factor test was used to test for the common method bias. All the original items were subjected to the factor analysis, where 19 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 were extracted. The first factor explained 32.71% of the variation, which was below the critical value of 40%, indicating that there was no serious common method bias in the data.

Descriptive Statistical Analysis and Correlation Analysis

The results of both the descriptive statistical analysis and the zero-order correlation analysis are exhibited in Table 2 which depicts that loneliness is positively correlated with social connection, self-control and NSSI (Rs = 0.469–0.753, Ps < 0.001). There was a significant positive correlation between loneliness and NSSI (R = 0.469, P < 0.001), which supports Hypothesis 1. In addition, social connection (R = −0.454, P < 0.001) and self-control (R = 0.431, P < 0.001) were also significantly correlated with NSSI.

|

Table 2 Descriptive Statistics |

Mediating Model Test

Bootstrapping was used to generate the empirical sample distribution of the statistics (ie, the mediating effect), from which confidence intervals (hereinafter “CI”) and standard errors were derived to determine the statistical significance of the mediating effect.65 In order to test the mediating effect of self-control and social connection on the relationship between loneliness and NSSI, the AMOS 24.0 was used for the bootstrap method, which was repeated 5000 times with a 95% confidence interval. The bias correction method was used to test the fitting degree of the model, where χ2= 309.227, df = 97, χ2/df = 3.188, CFI = 0.953, TLI = 0.942, GFI =0.907, NFI = 0.934, and RMSEA = 0.073. See Figure 1 for the standard fit indices in relation to the individual paths. The above fitting indexes are in line with the fitting standard, indicating that the model has a good fitting effect. Participants’ loneliness (β= 0.25, t = 3.88, p < 0.001) and self-control (β= 0.24, t = 4.08, p < 0.001) significantly predicted their NSSI, whereas their social connection (β= 0.09, t = 1.77, p > 0.05) did not.

|

Figure 1 Structural equation model fit test. Abbreviations: F1, Loneliness; F2, Self-control; F3, Social connectedness; F4, NSSI. |

The standardized mediation effects of the above variables were calculated by assigning all relevant paths through self-written grammars in a structural equation model. As exhibited in Table 3, in the mediating path of self-control between loneliness and NSSI, the standardized coefficient of prediction effect of loneliness on NSSI is β = 0.286, and P < 0.01. The standardized coefficient of the mediating effect of self-control between loneliness and NSSI was β= 0.143, P < 0.001, 95% CI was [0.066, 0.241] (excluding 0), indicating that self-control had a significant mediating effect between loneliness and NSSI, and the mediating effect was 33.33%. Therefore, hypothesis 2 is valid. In addition, the mediating effect of self-control on loneliness and social connection was significant (β= 0.120, p < 0.001), however, the mediating effect of social connection on loneliness and NSSI was not significant (β= 0.079, p > 0.05). The mediating effect of social connection between self-control and NSSI was not significant (β= 0. 029, p > 0.05), and the chain mediating effect of social connection between loneliness, self-control and NSSI was not significant (β= 0. 016, p > 0.05) as well.

|

Table 3 Mediation Effect Test |

Moderating Model Test

On the basis of the controlling gender, family structure and family economic level, the study made use of the Model 59 of PROCESS plug-in to estimate the 95% confidence interval of the mediating effect by sampling 5000 Bootstrap samples, and further analyzed the moderating effect of social connection on loneliness, self-control and NSSI. Table 4 exhibits that the moderating effect of social connection on loneliness and self-control is not significant (β= −0.037, t = −0.944, p > 0.05), and hypothesis 3A is therefore not valid; However, the moderating effect of social connection between loneliness and NSSI was significant (β= 0.107, t = 3.47, p < 0.001), and the moderating effect of social connection between self-control and NSSI was significant (β= 0.142, t = 3.34, p < 0.001), which supported hypotheses 3B and 3C.

|

Table 4 Moderated Model Test |

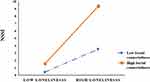

In addition, we used the method of Simple slope test for binary interaction terms introduced by Aiken and West66 to perform the Slop test to observe the effect of regulation with regards to social connection. Figure 2 exhibits that the NSSI of individuals with high levels of loneliness is greater than that of individuals with low levels of loneliness. Therefore, when affected by different degrees of social connection, the lonelier individuals are, the quicker their NSSI can increase. As can be seen from Figure 3, the NSSI of individuals with high a level of self-control is larger than that of individuals with a low level of self-control, and similarly, the NSSI of the former increases faster when they are affected by different degrees of social connection. The above results further validate Hypotheses 3B and 3C.

|

Figure 2 Moderating effect of Social connectedness on Loneliness and NSSI. |

|

Figure 3 Moderating effect of Social connectedness on Self-control and NSSI. |

Discussion

This study investigated how loneliness affects junior high school adolescents’ NSSI behavior, and the mediating role of self-control between loneliness and NSSI. It further explored how social connection participates in the moderating effects of loneliness, self-control and NSSI. The findings of this study are consistent with the conclusions of previous studies that there is a significant positive correlation between adolescents’ loneliness and NSSI.8–10,47 It is therefore necessary and important to pay more attention to adolescents’ loneliness to prevent and intervene adolescents’ NSSI.

The data analysis of this study also found that there was a significant positive correlation between self-control and adolescent loneliness and NSSI. This means, the lower the self-control ability of adolescents, the more serious their NSSI. This result indirectly supports the view of the self-control theory which states that low self-control is the main cause of violence and risk-taking behavior.25,26 According to the theory of experiential avoidance function, the main reason for an individual’s NSSI behavior is to avoid or escape the individual’s unwanted internal experience or behavior.67 Self-control is the ability of an individual to resist immediate temptation or endure immediate pain and unhappiness for an ideal long-term goal.18,19 Adolescents who have NSSI, may be unable to implement effective self-control (ie, to avoid unwanted internal experiences or behaviors), which leads to NSSI. In addition, individuals with a high level of self-control have a positive attitude towards life, a good psychological adjustment ability, the ability to cope with negative thoughts, and the ability to control behavior.31,32 From this point of view, it may be helpful for adolescents to strengthen their ability to exercise self-control to avoid or reduce NSSI.

Both the results of this study and previous research experience exhibit that loneliness is significantly related to self-control, and self-control is also significantly related to NSSI.27,33 In addition, self-control played a significant mediating role between loneliness and NSSI. The results of the above analysis further support the view that a lack of self-control is associated with higher loneliness, which can lead to social exclusion and active or passive solitude (loneliness), leading to a decline in self-control.35 This suggests that self-control plays an important role in the relationship between loneliness and NSSI. According to Zhang et al63 self-control relates to the certain standards or norms formulated by an individual in accordance to the needs of the situation and the intention of the subject, which are then implemented or stopped, insisted or given up on in order to change their behavior. Conversely, adolescents may also be unable to effectively control themselves in the face of loneliness, which results in NSSI occurring; Alternatively, from a positive perspective, self-control is the ability of an individual to autonomously regulate behavior so that it matches personal values and social expectations;22,23 adolescents can also reduce the impact of loneliness on NSSI by increasing the level of self-control that is positive.

Through a descriptive analysis, a negative correlation between social connection and adolescents’ NSSI has been found, this means, the lower adolescents’ degree of social connection, the more serious the situation of adolescents’ NSSI is. Social connection is an individual’s subjective perception of the closeness of interpersonal relationships in their social lives.38 The interpersonal function theory also emphasizes that poor social relationships may lead to NSSI.45,46 In addition, the evolutionary theory of loneliness suggests that loneliness may operate through a social distress mechanism that motivates people to repair and maintain social ties.43 The results of this study support the above theories and opinions. In addition, the mediating effect test found that self-control played a mediating role between loneliness and social connection. Therefore, the relationship between self-control and loneliness as well as NSSI is also supported. However, the path analysis of the structural equation model exhibits that the path analysis of social connection and NSSI is not significant, the mediating effect of social connection on loneliness and NSSI is not significant, and the mediating effect of social connection on self-control and NSSI is not significant. The results of the above analysis suggest that social connection plays other roles in the relationship between loneliness, self-control and NSSI.44

By making use of the moderating effect of Model 59 in the PROCESS plug-in,64 it was discovered that social connection played a moderating role between loneliness and NSSI, and that social connection also played a moderating role between self-control and NSSI. The results further support the view of the interpersonal function theory that when people feel lonely, they are more inclined to participate in various forms of social interaction to regulate their emotions, thereby reducing negative emotions and loneliness; Alternatively, individuals may also prevent or mitigate NSSI by gaining support or increasing contact with others (a self-control action that is positive).44–46 In addition, adolescents’ peers and friends are key sources of support for mental health problems and NSSI.49 Therefore, when intervening adolescents’ NSSI, more consideration should be given to strengthening the social connection between adolescents and their peers and friends, which will assist them in overcoming NSSI. It is worth noting that although social connection can promote the development of self-control,56 the data analysis in this study found that the moderating effect of social connection between loneliness and self-control was not validated. This may be because those who feel lonely are more likely to feel powerless and anxious in interpersonal relationships (lack of self-control cognition or the ability thereof) and may spend less time on social activities, which further weakens their social ties and makes it difficult to for them to maintain stable interpersonal relationships.52 This is the main reason for individuals experiencing loneliness, but it is also an obstacle with regards to eliminating loneliness.53

Conclusion

This study explored the relationships among loneliness, NSSI, self-control and social connectedness in junior high school adolescents. The results not only revealed that a positive relationship exists between loneliness and NSSI, but also the mediating role of self-control between loneliness and NSSI. In addition, social connection played a moderating role between loneliness and NSSI, and between loneliness and self-control. The moderating mediation model not only responds to the question of how being socially connected can affect NSSI in junior high school adolescents, but also answers the question related to what conditions the indirect predictive effect of social connectedness on NSSI and the mediating effect of self-control are more significant, which is of positive significance for deepening and expanding the research on the relationship between loneliness and individual psychological and behavioral adaptation.

This study, however, faced some limitations. First, the sample size of the study does not cover all possibilities, especially that of the adolescent group which includes not only junior high school students, but also senior high school students. Second, the sample selection is limited to a city in Sichuan Province, China, which does not consider the fact that China has great cultural differences in its different regions. As a result, the representativeness of this study’s group of samples may not be enough to cover the characteristics of Chinese adolescents in general. Finally, the cross-sectional survey adopted in this study needs more longitudinal experimental studies in the future to explore social connection and the moderating effect between loneliness, self-control and NSSI, in order to provide more sufficient evidence.

Data Sharing Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

This study and its research programs were approved by the Ethics Committee of Human Research Ethics Committee of Yibin University, China (2022-04-21-01Y). All methods were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the aforementioned ethics committee. All participants were informed about the contents of the survey and obtained their consent, as well as the informed consent of the participants’ parents or legal guardians and the class teacher.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the administrators and class teachers of A and B middle schools in Luzhou City, as well as the participants and their parents for their active cooperation, whose help enabled the smooth development of this study. Meanwhile, we would like to thank Yibin University, Hechi University and other institutions for their full support in ethical review, research and coordination.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

There is no funding to report.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Farber SK, Jackson CC, Tabin JK, et al. Death and annihilation anxieties in anorexia nervosa, bulimia, and self-mutilation. Psychoanal Psychol. 2007;24(2):289. doi:10.1037/0736-9735.24.2.289

2. Tang HM, Chen XL, Lu FT, et al. Meta-analysis of the relationship between bullying and non-suicidal self-harm in adolescents. Chin J Evid Based Med. 2018;7:707–714.

3. Geulayov G, Mansfield K, Jindra C, et al. Loneliness and self-harm in adolescents during the first national COVID-19 lockdown: results from a survey of 10,000 secondary school pupils in England. Curr Psychol. 2022:1–12. doi:10.1007/s12144-022-03651-5

4. Smoyak SA. Loneliness: a sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1984;22(6):40–41. doi:10.3928/0279-3695-19840601-09

5. Perlman D, Peplau LA. Theoretical approaches to loneliness. Loneliness Sourcebook Curr Theor Res Ther. 1982;36:123–134.

6. de Jong-Gierveld J. Developing and testing a model of loneliness. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;53(1):119. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.53.1.119

7. Brechwald WA, Prinstein MJ. Beyond homophily: a decade of advances in understanding peer influence processes. J Res Adolescence. 2011;21(1):166–179. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00721.x

8. McClelland H, Evans JJ, Nowland R, et al. Loneliness as a predictor of suicidal ideation and behaviour: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Affect Disorders. 2020;274:880–896. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.004

9. Carr A, Cullen K, Keeney C, et al. Effectiveness of positive psychology interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Posit Psychol. 2021;16(6):749–769. doi:10.1080/17439760.2020.1818807

10. Jollant F, Roussot A, Corruble E, et al. Hospitalization for self-harm during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic in France: a nationwide retrospective observational cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Eu. 2021;6:100102. doi:10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100102

11. Calati R, Ferrari C, Brittner M, et al. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors and social isolation: a narrative review of the literature. J Affect Disorders. 2019;245:653–667. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.022

12. McClelland H, Evans JJ, O’Connor RC. Exploring the role of loneliness in relation to self-injurious thoughts and behaviour in the context of the integrated motivational-volitional model. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;141:309–317. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.07.020

13. Palmer BW. The effects of loneliness and social isolation on cognitive functioning in older adults: a need for nuanced assessments. Int Psychogeriatr. 2019;31(4):447–449. doi:10.1017/S1041610218001849

14. Evans E, Hawton K, Rodham K. Factors associated with suicidal phenomena in adolescents: a systematic review of population-based studies. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24(8):957–979. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2004.04.005

15. Klonsky ED, Glenn CR, Styer DM, et al. The functions of nonsuicidal self-injury: converging evidence for a two-factor structure. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2015;9(1):1–9. doi:10.1186/s13034-015-0073-4

16. Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, et al. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol Rev. 2010;117(2):575–600. doi:10.1037/a0018697

17. Forkmann T, Glaesmer H, Paashaus L, et al. Interpersonal theory of suicide: prospective examination. BJ Psych Open. 2020;6(5):

18. Karoly P, Kanfer FH, eds. Self-Management and Behavior Change: From Theory to Practice. Vol. 106. Pergamon;1982.

19. Mead NL, Baumeister RF, Gino F, Schweitzer ME, Ariely D. Too tired to tell the truth: self-control resource depletion and dishonesty. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2009;45(3):594–597. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2009.02.004

20. Kim Y, Richards JS, Oldehinkel AJ. Self-control, mental health problems, and family functioning in adolescence and young adulthood: between-person differences and within-person effects. J Youth Adolescence. 2022;51:1181–1195. doi:10.1007/s10964-021-01564-3

21. Zhang YY. High School Students Learning Self-Control and Academic Self-Concept Studies [Master’s Degree Thesis]. Fujian Normal University; 2006. Available from: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=wAwtVZlv7YoyfuxWsGFxVC0h6NqHaNBNLVlaHqsTZ5UmLv_kHGnUftX17qYUSiB76ZCj7lE5BYLSMcVZITeyahlX-HutgIICu7TiQy8wWYiODJaEsRFWOw==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS.

22. Kopp CB. Antecedents of self-regulation: a developmental perspective. Dev Psychol. 1982;18(2):199–214. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.18.2.199

23. Deng CP, Liu JH. Countermeasures of children’s self-control education. Psychol Sci. 1998;03:270–271. doi:10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.1998.03.023

24. Stavrova O, Ren D, Pronk T. Low self-control: a hidden cause of loneliness? Pers Soc Psychol B. 2022;48(3). doi:10.1177/014616722110072

25. Gottfredson MR, Hirschi T. A General Theory of Crime. Stanford University Press. 1990. doi:10.1515/9781503621794

26. Mancinelli E, Ruocco E, Napolitano S, Salcuni S. A network analysis on self-harming and problematic smartphone use – the role of self-control, internalizing and externalizing problems in a sample of self-harming adolescents. Compr Psychiat. 2022;112:152285. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2021.152285

27. Özdemir Y, Kuzucu Y, Ak Ş. Depression, loneliness and Internet addiction: how important is low self-control? Comput Hum Behav. 2014;34:284–290. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.02.009

28. Muraven M, Baumeister RF. Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: does self-control resemble a muscle? Psychol Bull. 2000;126(2):247–259. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.247

29. Schmeichel BJ, Zell A. Trait self‐control predicts performance on behavioral tests of self‐control. J Pers. 2007;75(4):743–755. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00455.x

30. Oliva A, Antolin-Suarez L, Rodriguez-Merinhos A. Uncovering the link between self-control, age, and psychological maladjustment among Spanish adolescents and young adults. Psychosoc Interv. 2019;28(1):49–55. doi:10.5093/pi2019a1

31. Heatherton TF. Neuroscience of self and self-regulation. Annu Rev Psychol. 2011;62:363–390. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131616

32. Hofmann W, Friese M, Strack F. Impulse and self-control from a dual-systems perspective. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2009;4(2):162–176. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01116.x

33. Chen X, Zhang G, Chen H, Li D. Performance on delay tasks in early childhood predicted socioemotional and school adjustment nine years later: a longitudinal study in Chinese children. Int Perspect Psychol Res Pract Consult. 2012;1(1):3–14. doi:10.1037/a0026363

34. Evers C. Emotion regulation and self-control: implications for health behaviors and wellbeing. In: de Ridder D, Adriaanse M, Fujita K, editors. The Routledge International Handbook of Self-Control in Health and Well-Being. Routledge; 2018:317–329. doi:10.4324/9781315648576-25

35. Baumeister RF, DeWall CN, Ciarocco NJ, Twenge JM. Social exclusion impairs self-regulation. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;88(4):589–604. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.88.4.589

36. Liu J, Xiao B, Hipson WE, Coplan RJ, Li D, Chen X. Self‐control, peer preference, and loneliness in Chinese children: a three‐year longitudinal study. Soc Dev. 2017;26(4):876–890. doi:10.1111/sode.12224

37. Fried L, Prohaska T, Burholt V, et al. A unified approach to loneliness. Lancet. 2020;395:114. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(19)32533-4

38. Lee RM, Robbins SB. The relationship between social connectedness and anxiety, self-esteem, and social identity [Editorial]. J Couns Psychol. 1998;45(3):338–345. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.45.3.338

39. Shaw RJ, Cullen B, Graham N, et al. Living alone, loneliness and lack of emotional support as predictors of suicide and self-harm: a nine-year follow up of the UK Biobank cohort. J Affect Disorders. 2021;279:316–323. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.026

40. Rice S, Robinson J, Bendall S, et al. Online and social media suicide prevention interventions for young people: a focus on implementation and moderation. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;25(2):80–86. PMCID: PMC4879947.

41. LaRose R, Lin CA, Eastin MS. Unregulated Internet usage: addiction, habit, or deficient self-regulation? Media Psychol. 2003;5(3):225–253. doi:10.1207/S1532785XMEP0503_01

42. Lodder GMA, Goossens L, Scholte RHJ, et al. Adolescent loneliness and social skills: agreement and discrepancies between self-, meta-, and peer-evaluations. J Youth Adolescence. 2016;45:2406–2416. doi:10.1007/s10964-016-0461-y

43. Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC. Social isolation and health, with an emphasis on underlying mechanisms. Perspect Biol Med. 2003;46(3):S39–S52. doi:10.1353/pbm.2003.0063

44. Holt-Lunstad J. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors: the power of social connection in prevention. AM J Lifestyle Med. 2021;15(5):567–573. doi:10.1177/15598276211009454

45. Nock MK. Actions speak louder than words: an elaborated theoretical model of the social functions of self-injury and other harmful behaviors. Appl Prevent Psychol. 2008;12(4):159–168. doi:10.1016/j.appsy.2008.05.002

46. Nock MK, Prinstein MJ. Contextual features and behavioral functions of self-mutilation among adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005;114(1):140. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.140

47. Peel‐Wainwright KM, Hartley S, Boland A, Rocca E, Langer S, Taylor PJ. The interpersonal processes of non-suicidal self-injury: a systematic review and meta-synthesis. Psychol Psychother-T. 2021;94(4):1059–1082. doi:10.1111/papt.12352

48. Yan BB, Zheng X, Zhang XG. The mediating role of Self-control and depression in the Influence of Social support on subjective well-being of college students. Psychol Sci. 2011;02:471–475. doi:10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.2011.02.009

49. Migliorini L, De Piccoli N, Cardinali P, et al. Contextual influences on Italian university students during the COVID-19 lockdown: emotional responses, coping strategies and resilience. Commun Psychol Global Perspect. 2021;7(1):71–87. doi:10.1285/i24212113v7i1p71

50. Dellinger‐Ness LA, Handler L. Self‐injury, gender, and loneliness among college students. J Coll Couns. 2007;10(2):142–152. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1882.2007.tb00014.x

51. Li L, Liu Y. The relationship between college students’ self-esteem and happiness: social support the intermediary role of. Chin J Health Psychol. 2013;21(4):628–629. doi:10.13342/j.carolcarrollnkiCJHP.2013.04.027

52. Jones WH, Hobbs SA, Hockenbury D. Loneliness and social skill deficits. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1982;42(4):682–689. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.42.4.682

53. Ni L. Analysis on the relationship between loneliness, depression and suicidal behavior of college students. Science Tribune. 2013. doi:10.16400/j.carolcarrollnkiKJDKS.2013.09.019

54. Yates TM. The developmental psychopathology of self-injurious behavior: compensatory regulation in posttraumatic adaptation. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24(1):35–74. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2003.10.001

55. Li J, Zhan D, Zhou Y, Gao X. Loneliness and problematic mobile phone use among adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: the roles of escape motivation and self-control. Addic Behav. 2021;118:106857. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106857

56. Hill TD, Burdette AM, Jokinen-Gordon HM, Brailsford JM. Neighborhood disorder, social support, and self–esteem: evidence from a sample of low–income women living in three cities. City Commun. 2013;12(4):380–395. doi:10.1111/cico.12044

57. Lee RM, Draper M, Lee S. Social connectedness, dysfunctional interpersonal behaviors, and psychological distress: testing a mediator model. J Couns Psychol. 2001;48(3):310–318. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.48.3.310

58. Olga B, Vladimir S. The digital capital of social services consumers: factors of influence and the need for investment. J Soc Policy Stud. 2021;19(1):129–142.

59. Heinrich LM, Gullone E. The clinical significance of loneliness: a literature review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26(6):695–718. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2006.04.002

60. Zou H. Adolescent Peer Relationship: Developmental Characteristics, Functions and Influencing Factors. Beijing Normal University Press; 2003:73–98.

61. Hu FJ, Chen G, Cai TH. The test of self-control scale in middle school students. Chin J Health Psychol. 2012;8:1183–1184. doi:10.13342/j.carolcarrollnkiCJHP

62. Fan XL, Wei J, Zhang JF. Reliability and validity test of the revised social connection scale in middle school students. J Southwest Norm Univ. 2015;118–122. doi:10.13718/j.carolcarrollnkiXSXB.2015.08.022

63. Zhang F, Cheng WH, Xiao ZP. Research status of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury behavior. Chin J Psychiatry. 2014;47(5):308–311.

64. Hayes AF. PROCESS: a versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [White paper]; 2012. Available from http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf.

65. Zhao X, Lynch JG, Chen Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: myths and truths about mediation analysis. J Consum Res. 2010;37(2):197–206. doi:10.1086/651257

66. Aiken LS, West SG, Reno RR. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Sage; 1991.

67. Chapman AL, Gratz KL, Brown MZ. Solving the puzzle of deliberate self-harm: the experiential avoidance model. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(3):371–394. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2005.03.005

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.