Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

The Effect of Competence-Building Narrative on Chinese Adolescents’ Persistence

Authors He W, Ming Z, Huang L, Chen T

Received 24 January 2023

Accepted for publication 3 May 2023

Published 12 May 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 1787—1795

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S404950

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Wuming He,1,2 Zhu Ming,1,2 Lulu Huang,2,3 Tiancai Chen4

1Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Development and Education for Special Needs Children, Zhanjiang City, Guangdong Province, People’s Republic of China; 2School of Education Science, Lingnan Normal University, Zhanjiang City, Guangdong Province, People’s Republic of China; 3Xinyi No.2 High School of Guangdong, Xinyi City, Guangdong Province, People’s Republic of China; 4Zhanjiang Aizhou Middle School, Zhanjiang City, Guangdong Province, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Zhu Ming, Email [email protected]

Abstract: Persistence is one of the most critical aspects of learning motivation, but little attention has been paid to persistence intervention in the literature. The current study took a perspective from narrative psychology to examine the effect of narrative form on junior middle school students’ ability to persist. Thirty-two students were randomly assigned to the experimental group of competence-building narrative and the control group. While all the students constructed past experiences of success and failure, those in the experimental group were prompted to think from a competence-building perspective. Then both groups solved a figure-based problem, within which the researcher recorded their number of attempts and time spent. Results showed that those who construct past success and failure from a competence-building perspective attempted more times and spent more time on the unsolvable problem.

Keywords: narrative psychology, persistence, narrative intervention, adolescents, motivation

Introduction

Persistence is the ability to overcome difficulties to achieve one’s goal persistently.1 Persistence is one of the essential components of willpower. Several survey studies indicated that persistence is vital to self-regulated learning.2,3 For example, learning engagement mediates the positive effect of persistence on primary school students’ academic achievement.4 The junior and senior high school students’ persistence is positively correlated with their application of learning strategies, with which they gain higher academic achievement.5 The persistence of junior high school students mediated the impact of learning interest and learning self-efficacy on math academic achievement.6 A content analysis of structured self-regulated learning interviews showed that the persistence of junior high school students in applying learning strategies is the most influencing factor for academic achievement.7

Despite the importance of persistence to learning engagement, learning strategies, and academic achievement, it is somewhat surprising that so little research has been conducted on improving adolescent persistence performance. There are a few experimental studies investigating antecedents of persistence for infants or young children, such as the playing context of infants,8 pressure context and material properties,9 and attitude and instructional types of teachers.10,11 However, individual differences in persistence expand as students age.1,12 So the results may not be transferrable or generalizable to adolescents. There has been much less experimental research on the persistence intervention for adolescence. This study investigates the effect of narrative formation on adolescents’ persistence to contribute to the literature.

The perspective of narrative psychology may be a promising way to intervene in students’ motivation performance. A personal life narrative or life story is the process and product of thinking about, constructing, and narrating past experiences. The personal narrative has been suggested to be the core of personality.13 Through restructuring past experiences and imagined futures, personal life narratives or life stories offer a person’s life unity, purpose, and meaning. One person’s motivational systems have been placed under the construct of characteristic adaptation in the framework of McAdams’ “five principles of personality psychology”.13 Characteristic adaptations are concerned with the motivational aspect of humans, including motives, goals, plans, strivings, values, and schemas. Costa and McCrae suggested that characteristic adaptations are specific patterns of behavior that can be shaped by dispositional traits and by situational variables.14 As suggested, a life narrative can influence one’s characteristic adaptation, including the motive process.13 Personal life narratives theoretically shape persistence as the characteristic of motivation. More importantly, accumulating evidence suggests that narrative identity is malleable, which means people are able to reconstruct their experiences.15 This assumption gives a way to develop interventions through constructing one’s life story. Further, evidence suggests that the reconstructed narrative can impact students’ performance. For example, constructing a positive self-narrative can promote academic performance.16,17

Additionally, according to the regulatory focus theory of motivation,18 two distinctive motivational systems direct people’s behavior to pursue their goals: the promotion system that emphasizes obtaining success and growth; the prevention system that emphasizes avoiding failure and keeping the self safe. However, the regulatory focus has been viewed as one of the individual differences that are somewhat chronic. From the perspective of life narrative,13 it can be malleable because it is a dynamic motivational system that involves dynamics from life narratives and situational influences. Prior research showed that people’s narrative interpretation of past experiences could be categorized as the type that emphasizes growth or safety. From this point of view, it is possible to reconstruct past experiences to be promotion-focused, which makes sense of one’s experience by constructing a story of growth. We infer that this process of narrating one’s past experiences can drive his/her goal-directed behavior more persistently. Evidence suggests that the personal history of one’s adolescence is remembered the best and is the densest relative to any other development period.19 This age period is also the transition stage to adulthood from which narrative identity emerged.20 So this period of age provides a fertile repertoire of stories for adolescents to cultivate their narrative identity.

A personal narrative can be analyzed from two dimensions: structure and content. The competence-building narrative, proposed by Jones et al,21 comprises two themes: agency and redemption. That is, participants were instructed to narrate their agency in success experiences and the positive aspects of failure experiences. Preliminary evidence suggests that the competence-building narrative increases adolescents’ persistence.21 However, their two studies measured goal persistence with a self-reported questionnaire, ie, the grit scale. Persistence is a socially desirable trait; individuals might over-report their persistence. The same grit scale was measured twice in their Study 2 at two time points, which could make the researcher’s intention overt to the participants. In addition, the self-reported measures could be somewhat distanced from students’ daily context. In contrast, behavioral assessments are non-self-report measures, which tend to be more covert so that participants are less likely to guess the researcher’s hypothesis.22 Behavioral measures can elicit real responses that increase psychological realism. Therefore, in the present study, we employed a behavioral measurement of persistence by putting them in a situation of solving problems and assessing their persistence in performance. We recruited junior high school students and assigned them randomly to the experimental and control group. Both groups of participants were instructed to tell their life stories about success and failure, but only the experimental group was prompted to narrate from a competence-building perspective, ie, think of their agency from success and growth from failure.

In sum, the life story theory suggests that constructing a positive self-narrative can motivate a person through shaping characteristic adaptation, which is the personality’s core motivational component. The regulatory focus theory suggests that constructing a growth story from past experience can make people promotion-focused, which drives them to their goals. The personal narrative studies suggest that thinking of previous experiences from a perspective of agency and redemption can make people’s strivings persistent. Therefore, based on the reasoning from life story theory, regulatory focus theory, and narrative themes of agency and redemption, we hypothesized that compared to the control group, participants in the competence-building narrative group would perform better in terms of persistence when facing a difficult task. We also employed behavioral measures to address previous research’s limitation of self-report measures in the field.

Methods

Participants

Thirty-two students (male:21) from a key middle school were recruited, aged 12 to 15 (M=13, SD=0.83). They were randomly assigned to the experimental group and the control group, each contained 16 participants. They all scored in the lower half of all students on the last scholastic tests, with their averaged percentile rank being 46.9% (the experimental group) and 47.2% (the control group). Before sampling, we reviewed previously reported effect sizes in the literature. Previous studies recorded high effect sizes. For example, students narrating competence-building themes in both failure and success stories scored higher in goal persistence than other students with a high effect size of Cohen’s d = 1.10.21 We used a comparable intervention in a lab environment, and the effect direction was determined (to be positive). We estimated the sample size necessary to achieve a power level of 0.80 for an expected high-sized effect of Cohen’s d = 0.90 using the G*Power.23 The results suggested a total sample size of 32, with 16 for each group.

The Grit Scale

The original version of the Grit Scale24 was revised and compiled to the Chinese version and exhibited satisfactory reliability and validity.25 It consists of eight items, including dimensions of stability of interests (sample items include “I often become obsessed with an idea or project for a short period of time, but then lose interest”) and steadiness of efforts (sample items include “Setbacks will not discourage me”). Each dimension includes four items, which is anchored on Likert 5 scale. Higher scores indicate higher grit, which means stronger persistence in terms of trait. The purpose of the use of the Grit Scale was to measure participants’ trait persistence to confirm the validity of the random assignment, making sure the experimental group and the control group were paralleled on grit in the starting point. The Cronbach α was 0.74 in the sample of the current study.

Narrative Intervention

The way of narrative intervention was adapted from Jones et al.21 All participants were asked to write on a blank paper to tell about life events of both success and failure they experienced. In this way, it is assumed that participants construct their narratives of success and failure in the past. In contrast to the control group, participants in the experimental group were instructed to think of their past from a competence-building perspective. For instance, the researcher required participants to think of and tell about “what measures you take to achieve the success” and describe “through what way the failure bring about good change to you”. Participants in the control group also constructed their past success and failure. However, there is no such instruction prompted to them.

Unsolvable Task

Persistence is operationalized as the number of times attempted and the duration of time used to solve a problem. These indicators has been used successfully in previous studies.26–28 In the present study, it is measured using an unsolvable task adapted from previous study,27,29 which is a figure-based reasoning task. Its advantage includes avoiding culturally specific or content specific bias. For instance, math or reading comprehension problems may intrigue different levels of interest among participants.

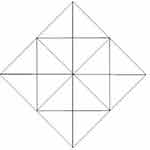

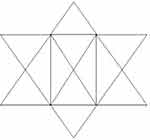

Participants were given two stacks of paper. Each paper contained a line diagram and was stacked in piles. The diagram in each stack was different (see Figures 1 and 2). Participants were asked to use a pen to trace over all the lines in the diagram in one attempt without tracing over any line twice, and lifting the pen was not permitted in one attempt. If they failed, they could start a novel attempt with another paper. Additional instruction from the researcher included,

I will show you two diagrams on the paper. They are different in the level of difficulty. The first diagram to trace is very difficult. There is only 5% of students would complete it. The second diagram is moderately difficult. The rate of success is 50%. I will give you the first diagram in the first. You can try your best to do it. If you think it is beyond your effort to figure it out, you can tell me to shift to the second diagram at any time.

|

Figure 1 The unsolvable diagram. |

|

Figure 2 The solvable diagram. |

In fact, the first diagram was unsolvable, so each trial in the first task would fail. The second one was solvable. Any time the participant informed the researcher to proceed to the second item, the recording of the number of novel attempts and the time he/she spent in the task was also ended. If the participant did not proceed to the second item after starting 20 minutes, the researcher would remind him/her that he/she can shift to the second one at any time. The researcher would remind them again after 35 minutes and inform them to end the attempts for the first diagram at 60 minutes. Two measures were recorded: the number of novel trials taken at the first diagram before turning to the second diagram; the total time spent from the time the participant started the first item to the point of time he/she decided to take the second diagram.

Procedures

Participants were invited to participate in the experiment with their consent. After the participants agreed, researchers contacted the teachers in charge of the class and sought their consent in the teacher-parent meeting. The subjects were instructed to complete each experiment alone. Each subject was randomly assigned to an experimental group or a control group. All subjects first completed the Chinese version of the abbreviated persistence questionnaire as a baseline-level test of persistence to check and confirm that there was no difference in baseline persistence between the two groups. Then, the experimental group completed the competence-building narrative alone in a quiet environment. At the same time, the control group completed a narrative about their experience of success and failure without competence-building thinking. Finally, all participants completed the unresolved task. All data were input and analyzed by SPSS 20.0.

Results

We conducted independent sample t-tests for the experimental group and the control group. Results showed that there was no difference between the control group (M = 2.95, SD = 0.50) and the experimental group (M = 2.81, SD = 0.77) in the interest stability dimension: t (30) = 0.61, p = 0.546, d = 0.22; there was also no difference between the control group (M = 3.34, SD = 0.58) and the experimental group (M = 3.52, SD = 0.67) in the effort sustainability dimension: t (330) = −0.78, p = 0.442, d = 0.28; the control group (M = 3.15, SD = 0.47) and the experimental group (M = 3.16, SD = 0.64) were not significantly different in the scores for the whole persistence scale: t (30) = −0.08, p = 0.937, d = 0.03. The baseline test results indicated that the randomized assignment was effective, ensuring that there was no significant difference in persistence at the trait level of personality between the two groups.

One way ANOVA test showed that the competence-building narrative group (M = 39.38, SD = 18.00) attempted more times than the control group (M = 25.56, SD = 18.68) to solve the problem (mean difference = 13.82 with 95% CI [0.57, 27.06]), F(1, 30) = 4.54, p = 0.042, d = 0.75 with 95% CI [0.03, 1.47], see Figure 3. The experimental group (M = 25.88, SD = 11.72) also spent longer time (min) than the control group (M = 17.81, SD = 9.28) in solving the difficult task (mean difference = 8.07 with 95% CI [0.43, 15.70]), F(1,30) = 4.65, p = 0.039, d = 0.76 with 95% CI [0.04, 1.48], see Figure 4.

|

Figure 3 Number of attempts as function of narrative formation. |

|

Figure 4 Time spent as function of narrative formation. |

Discussion

The results confirmed our hypothesis: the competence-building narrative intervention makes junior high school students persist in solving the task: attempt more times and spend more extended time. The results are consistent with previous studies showing competence-building narrative intervention is valid in improving students’ persistence performance.21 Our results are worthwhile observations that complement previous studies and validate the effective role of personal narrative construction in motivating goal persistence. It also provides more evidence for the plasticity of the individual narrative, thus providing the basis for the further development and application of the narrative intervention. In addition, the results of our study contribute further evidence in a sample of Chinese adolescents, validating the effect of competence-building narrative on persistence.

One explanation for the effect of narrative interventions on persistence would be that the competence-building narrative helps self-meaning construction and promotes a positive mood within participants. Previous research indicates that students with lower anxious emotions are more likely to use self-regulated learning strategies and show stronger task persistence than those with higher anxious emotions.30 From a narrative psychology perspective, the students’ narrative of success or failure experiences is a recall of special events occurring in the past. These separate events lasting within 24 hours, whether the valence is positive or negative, are self-definingmemories.31 For example, the memory of a certain test or a certain ball match is a self-defining memory. Memories of these particular events are both a process and a capability.32 Being able to retrieve self-defining memories and connect them with the long-term self-structure is a process of meaning construction. So, the retrieval and narrative of self-defining memory can give the self-meaning and purpose. This is helpful to the self-identity question of “what I want to do”. If an individual cannot activate a self-defining memory, it can lead to psychological dysregulation. Studies have shown that memory has recovery effects on human mood regulation.33 When people are in negative situations, past negative events are more accessible, which is called the mood congruence effect on cognitive processing, but then the regression effect occurs, that is, originally optimistic people will recall more positive events, which reflects the person’s use of memory during mood regulation. Retrieval of self-defining memory is difficult for people with high self-defense. Therefore, guiding students to narrate makes them more willing to tell past stories. The narrative intervention can facilitate recalling defining memories and reconstructing them to integrate past experiences with current goals. This meaning-generation process helps improve students’ self-meaning, purpose, and mood, which in turn makes students more persistent in task performance.

The impact of competence-building narrative on persistence may also be achieved by enhancing self-efficacy. Self-efficacy can boost persistence performance. Some studies believe that Asian students have stronger achievement motivation and self-efficacy, better persistence, and behavior control.34 A correlational study found that the higher the self-efficacy of primary school students, the stronger the motivation and persistence in completing difficult tasks.35 Students with high learning efficacy use more self-regulated learning strategies and have greater task persistence.36 Self-efficacy is itself one of the important drivers of learning.37 Identity-based motivation theory suggests that the individual identity is continuously constructed, and the interpretation of events influences the construction of individual identity.38 Two ways of interpreting events can improve the self-regulation motivation: on the one hand, when people encounter obstacles in achieving their goals, they attribute these difficulties to the importance of the goal; on the other hand, when people succeed in the realization of the goal, they interpret the ease of the goal achievement to the possibility of solving problems. In the narrative intervention, participants considered the importance of the failure events by reflecting on their good aspects brought to them. They also summarized the experience of successful events by thinking about the solutions they used to achieve successes. These interpretations of the events can enhance their self-efficacy, which promotes their persistence performance.

In addition to the above theoretical contributions, this study offers practical implications concerning adolescents’ identity development. Adolescence is a rapid development period of narrative identity.39 Self-narrative is critical to the development of teenagers during adolescence period, during which their self-identity also develops quickly. The self-narrative pattern affects self-identity formation. Redemption sequence (redemption sequence) is one of the four main narrative patterns.40 That is, the narrator changes from a negative state to a positive state through a narrative process. Longitudinal tracking studies suggest that redemption-pattern narratives can drive a positive shift in behavior.41 In the experimental intervention, the competence-building narrative required participants to positively construct failure experiences, which helped participants to switch from negative to positive valence events. It is of great significance through narrative guidance to help teenagers establish a positive construction of past experiences in this period for future development.

Some differences distinguish the narrative intervention in the current study from other narrative interventions. First, previous narrative interventions mainly guided subjects to retrieve and describe positive content from their past experiences17 or directly present the modified story to participants for reading,16 and did not guide participants to deep cognitive processing. The narrative intervention of this study led participants to reconstruct both positive and negative content and change perspectives. The results imply that not only the content and structure, but the perspective of the narrative is feasible for intervention. Future narrative interventions can explore more different methods and compare their respective advantages. Second, the majority of narrative interventions in China are conducted through consulting conversations. Asians seem to prefer the non-verbal communication mode and the non-direct communication mode. Therefore, the narrative approach of non-direct communication may pose less threat to individuals and thus play a greater role than oral communication.42 Our results showed that thinking and writing are also practical for narrative interventions. Moreover, the inclusion of “storytelling” into the intervention may be more accessible to students in the new era. The results have implications for the consolidation and development of relevant narrative psychology theories and the application of narrative methods in practice. Changes in narrative style can affect personal self-identity in personality structures and then influence adaptive traits in personality structures closer to real life, including behavioral manifestations such as goal setting, planning implementation, and motivational processes.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the endurance of the effect has yet to be rated in the study. Future study is needed to examine how long it will last. Second, although the effect sizes are large, more research needs to consolidate the effect in the future. Third, whether the practice is valid in an actual situation? Large scale field study is needed to examine the intervention. Fourth, although the mood and self-efficacy explanations seem plausible, future research should provide empirical evidence.

Conclusion

In the current study, we provide additional evidence supporting the effect of the competence-building narrative intervention on junior high school students’ task persistence in a Chinese sample. The study adapted the original competence-building narrative task to a Chinese version and adopted a handwriting formation for the narrating task. We employed covert behavior measurement to measure goal persistence using an unsolvable line-tracing task. The study concludes that the competence-building narrative enhances Chinese adolescents’ persistence in solving a problem.

Data Sharing Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Lingnan Normal University (April 3, 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study. All participants’ parents and their teachers in charge of the class consent to involve in the study.

Funding

This study is supported by Humanity and Social Science Youth Foundation of Ministry of Education of China [18YJC880021], Guangdong Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning Project [GD20XJY56], Open Project Program of Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Development and Education for Special Needs Children [TJ202104], Yanling Excellent Young Teacher Program of Lingnan Normal University [YL20200201], and the 2022 Annual Research Project of Guangdong Education Association [GDES14298].

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

1. Lai CC. The study of infant persistence development. Psychol Sci Letters. 1988;4(59):58–60.

2. Peng J. Review and prospect of research on children’s persistence. Educ Guide. 2015;1:29–32.

3. Zhang L, Zhou GT. A review of self-regulated learning theory. Psychol Sci. 2003;26(5):103–106.

4. Wei J, Liu R, He Y, Tang M, Di M, Zhuang H. The mediating role of primary school students’ learning persistence and learning engagement in the relationship between perceived efficacy intrinsic value and academic achievement. J Psychol Behav. 2014;12(3):326–332.

5. Zhang L, Zhang XK. The relationship between learning strategy use, learning efficacy, learning persistence and academic achievement in middle school students. Psychol Sci. 2003;26(4):29–33.

6. Du XF, Liu J. The relationship between “math interest”, “math self-efficacy”, “learning persistence” and “math achievement” of eighth graders. J Mathematic Educ. 2017;26(2):29–34.

7. Zhou GT, Zhang L, Fu GF. The relationship between the use of self-regulation learning strategies and academic achievement in middle school students. Psychol Sci. 2001;24(5):612–613.

8. Che H. A practical study on the development of children’s volitional quality in situational games. Early Educ. 2013;6:26–32.

9. Peng J. The influence of stressful situations and material familiarity on children’s persistence. PhD Thesis. Southwest University; 2015.

10. Dan F, Feng L, Wang Q. The influence of teacher attitude and verbal guidance on persistence of 3–6 year old children. J Presch Educ Res. 2008;4:19–22.

11. Dan F, Feng L. An experimental study on the influence of teacher attitude and guidance style on children’s persistence. Educ Develop Psychol. 2009;25(1):7–13.

12. Peng D, Su H, Liu D. Individual differences in persistence development of small-class children. Early Childhood Educa. 2018;753:55–59.

13. McAdams DP, Pals JL. A new Big Five: fundamental principles for an integrative science of personality. Am Psychol. 2006;61(3):204–217. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.61.3.204

14. Costa PT, McCrae RR. Set like plaster? Evidence for the stability of adult personality. In: Heatherton TF, Weinberger JL, editors. Can Personality Change? American Psychological Association; 1994:21–40.

15. Adler JM. Living into the story: agency and coherence in a longitudinal study of narrative identity development and mental health over the course of psychotherapy. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2012;102(2):367–389. doi:10.1037/a0025289

16. Bikmen N. History as a resource: effects of narrative constructions of group history on intellectual performance: group history and intellectual performance. J Soc Iss. 2015;71(2):309–323. doi:10.1111/josi.12112

17. Nelson DW, Knight AE. The power of positive recollections: reducing test anxiety and enhancing college student efficacy and performance. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2010;40(3):732–745. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00595.x

18. Higgins ET. Promotion and prevention: regulatory focus as a motivational principle. In: Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Vol. 30. Elsevier;1998:1–46. doi:10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60381-0

19. Rubin DC, Rahhal TA, Poon LW. Things learned in early adulthood are remembered best. Mem Cognit. 1998;26(1):3–19. doi:10.3758/BF03211366

20. McAdams DP. The Stories We Live By: Personal Myths and the Making of the Self. Morrow; 1993.

21. Jones BK, Destin M, McAdams DP. Telling better stories: competence-building narrative themes increase adolescent persistence and academic achievement. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2018;76:76–80. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2017.12.006

22. Snyder ML, Kleck RE, Strenta A. Avoidance of the handicapped: an attributional ambiguity analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1979;37(12):2297–2306. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.37.12.2297

23. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41(4):1149–1160. doi:10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

24. Duckworth AL, Quinn PD. Development and validation of the Short Grit Scale (GRIT–S). J Pers Assess. 2009;91(2):166–174. doi:10.1080/00223890802634290

25. Liang W, Wang D, Zhang C, Si G. Reliability and validity of a simple willpower questionnaire in Chinese professional and university athletes. Chin J Sports Med. 2016;35(11):1031–1037.

26. Andrews GR, Debus RL. Persistence and the causal perception of failure: modifying cognitive attributions. J Educ Psychol. 1978;70(2):154–166. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.70.2.154

27. Feather NT. Persistence at a difficult task with alternative task of intermediate difficulty. J Abnormal Soc Psychol. 1963;66(6):604–609. doi:10.1037/h0044576

28. Zimmerman BJ, Blotner R. Effects of model persistence and success on children’s problem solving. J Educ Psychol. 1979;71(4):508–513. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.71.4.508

29. Feather NT. The relationship of persistence at a task to expectation of success and achievement related motives. J Abnormal Soc Psychol. 1961;63(3):552–561. doi:10.1037/h0045671

30. Hill KT, Wigfield A. Test anxiety: a major educational problem and what can be done about it. Elem Sch J. 1984;85(1):105–126. doi:10.1086/461395

31. Singer JA, Blagov PS Classification system and scoring manual for self-defining autobiographical memories. Connecticut College; 2000.

32. Singer JA, Blagov P, Berry M, Oost KM. Self-defining memories, scripts, and the life story: narrative identity in personality and psychotherapy. J Pers. 2013;81(6):569–582. doi:10.1111/jopy.12005

33. Josephson BR. Mood regulation and memory: repairing sad moods with happy memories. Cogn Emot. 1996;10(4):437–444. doi:10.1080/026999396380222

34. Zimmerman BJ, Risemberg R. Self-regulatory dimensions of academic learning and motivation. In: Handbook of Academic Learning. Elsevier; 1997:105–125.

35. Zimmerman BJ, Ringle J. Effects of model persistence and statements of confidence on children’s self-efficacy and problem solving. J Educ Psychol. 1981;73(4):485. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.73.4.485

36. Pintrich PR, De Groot EV. Motivational and self-regulated learning components of classroom academic performance. J Educ Psychol. 1990;82(1):33. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.82.1.33

37. Zimmerman BJ. Self-efficacy: an essential motive to learn. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2000;25(1):82–91. doi:10.1006/ceps.1999.1016

38. Oyserman D, Lewis NA, Yan VX, Fisher O, O’Donnell SC, Horowitz E. An identity-based motivation framework for self-regulation. Psychol Inq. 2017;28(2–3):139–147. doi:10.1080/1047840X.2017.1337406

39. He C, Zheng J. Research progress of narrative identity. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2016;24(2):376–380.

40. McAdams DP, Guo J. Narrating the generative life. Psychol Sci. 2015;26(4):475–483. doi:10.1177/0956797614568318

41. Dunlop WL, Tracy JL. Sobering stories: narratives of self-redemption predict behavioral change and improved health among recovering alcoholics. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2013;104(3):576–590. doi:10.1037/a0031185

42. Wu J. Research on the Effect of Narrative Style on Personality Development. Nankai University; 2010.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.