Back to Journals » International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease » Volume 11 » Issue 1

The burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease associated with maintenance monotherapy in the UK

Authors Edwards SC, Fairbrother SE, Scowcroft A, Chiu G, Ternouth A, Lipworth BJ

Received 2 April 2016

Accepted for publication 17 June 2016

Published 22 November 2016 Volume 2016:11(1) Pages 2851—2858

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S109707

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Dr Richard Russell

Susan C Edwards,1 Sian E Fairbrother,2 Anna Scowcroft,3 Gavin Chiu,4 Andrew Ternouth,3 Brian J Lipworth5

1Department of Market Access Pricing & Outcomes Research, 2Department of Medical Affairs - Respiratory, 3Department of Market Access, 4Department of Prescription Medicine - Respiratory, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bracknell, UK; 5Asthma and Allergy Research Group, Division of Cardiovascular and Diabetes Medicine, Scottish Centre for Respiratory Research, University of Dundee, Ninewells Hospital and Medical School, Dundee, UK

Background: This study characterized a cohort of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients on maintenance bronchodilator monotherapy for ≥6 months to establish their disease burden, measured by health care utilization.

Methods: Data were extracted from the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink and linked to Hospital Episode Statistics. The monotherapy period spanned the first prescription of a long-acting β2-adrenergic agonist or a long-acting muscarinic antagonist until the end of the study (December 31, 2013) or until step up to dual/triple therapy, for example, addition of another long-acting bronchodilator, an inhaled corticosteroid, or both. A minimum of four consecutive prescriptions and 6 months on continuous monotherapy were required. Patients <50 years old at first COPD diagnosis or with another significant respiratory disease before starting monotherapy were excluded. Disease burden was evaluated by measuring patients’ rate of face-to-face interactions with a health care professional (HCP), COPD-related exacerbations, hospitalizations, and referrals.

Results: A cohort of 8,811 COPD patients (95% Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease stage A/B) on maintenance monotherapy was identified between 2002 and 2013; 45% of these patients were still on monotherapy by the end of the study. Median time from first COPD diagnosis to first monotherapy prescription was 56 days, while the median time on maintenance bronchodilator monotherapy was 2 years. The median number of prescriptions was 14. On average, patients had 15 HCP interactions per year, and one in ten patients experienced a COPD exacerbation (N=8,811). One in 50 patients were hospitalized for COPD per year (n=4,848).

Conclusion: The average monotherapy-treated patient had a higher than average HCP interaction rate. We also identified a large cohort of patients who were stepped up to triple therapy despite a low rate of exacerbations. The use of the new class of long-acting muscarinic antagonist/long-acting β2-adrenergic agonist fixed-dose combinations may provide a useful step-up treatment option in such monotherapy patients, before the use of inhaled corticosteroids.

Keywords: COPD, UK primary care setting, bronchodilators, prescribing patterns, monotherapy

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is an umbrella term used to describe chronic lung diseases that cause limitations in lung airflow, usually due to cigarette smoking.1 COPD is characterized by airflow obstruction that is usually progressive, partially reversible, and does not change markedly over several months.2 The most common symptoms of COPD are breathlessness, excessive sputum production, and chronic cough. Patients can also experience acute exacerbations usually associated with viral respiratory infections, which are a hallmark of COPD, further impairing the quality of life and health status.3 COPD is a highly prevalent and debilitating disease that has a significant impact on the costs borne by the health care system. According to the latest World Health Organization estimates, more than three million people died of COPD in 2012, which is equal to 6% of all deaths globally.3 The prevalence of COPD is difficult to estimate due to different definitions of COPD and underdiagnosis. In the UK, ~900,000 people have been diagnosed with COPD, while it is estimated that another two million people have COPD that remains undiagnosed.4

Inhaled bronchodilator medications such as long-acting β2-adrenergic agonists (LABA) or long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA) are the cornerstones of symptomatic COPD treatment. Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are also widely used in COPD management primarily to reduce the risk of exacerbations, especially in patients with an eosinophilic component.5 ICS are only licensed in combination with a LABA in the treatment of COPD. Their role in COPD is controversial, as the use of ICS is associated with a number of local and systemic side effects such as oral candidiasis, increased risk of pneumonia,6 and osteoporosis. This is reflected in treatment guidelines where the use of ICS is normally reserved as a second- or third-line maintenance treatment option.7 However, there is evidence to suggest that in the primary care setting in the UK, prescribers are not always following these guidelines, resulting in a substantial proportion of patients being inappropriately prescribed ICS.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) 2010 COPD guidelines recommend short-acting bronchodilators as reliever medication,2 and when these agents have failed to control symptoms, a long-acting maintenance bronchodilator (LABA or LAMA) is indicated. The NICE guidelines reserve the use of ICS as a first-line treatment for patients with forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) <50% or having exacerbations, or for those with symptoms not controlled on monotherapy. The Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2016 strategy recommends the use of ICS only for patients with severe or very severe airflow limitation and/or two or more exacerbations per year or any exacerbation leading to hospitalization.7

Further deterioration of lung function usually requires the progressive introduction of more treatments, both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic, attempting to limit the impact of these changes. As the disease progresses, patients with COPD may be stepped up to dual and triple therapy pharmacologic treatment regimens.

This retrospective study aimed to establish the burden of disease for COPD patients treated with maintenance bronchodilator monotherapy (either a LABA or LAMA) in the UK. To do so, we evaluated how many resources these patients used (ie, visits to a general practitioner [GP] and referrals to specialist care) and how many health issues they encountered (COPD exacerbations and hospitalizations) over the course of their monotherapy treatment period until these patients were stepped up to dual or triple therapy. As a marker of unmet need, we also studied the time taken to step up to dual/triple therapy for different monotherapy patient subgroups.

Patients and methods

Study population

This was a retrospective cohort study of COPD patients identified from primary care setting in the UK using the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD). The CPRD is a database of longitudinal patient primary care records, containing anonymized data of patient demographics, diagnoses, referrals, prescriptions, and health outcomes from over 660 GP practices in the UK. Validation studies have confirmed the high quality of the data and completeness of clinical records within the CPRD.8–12

Data from patients first diagnosed with COPD between January 2002 and December 2011 who were ≥50 years old at diagnosis were extracted from the CPRD. All patients with another significant respiratory disease (eg, asthma, bronchiectasis, lung cancer/carcinoma, cystic fibrosis, interstitial lung disease, and pulmonary thromboembolic disease) or a history of lung transplant prior to the start of monotherapy were excluded. In order to minimize the likelihood of including asthmatics or patients with both asthma and COPD diagnoses, the sample was restricted to patients aged ≥50 years at the time of COPD diagnosis.

Exposures

Patients had to be on either a LABA or a LAMA as monotherapy for at least 180 days. In addition, patients had to have at least 6 months of continuous CPRD records following the end of their specific period on monotherapy, that is, valid records, and be alive and enrolled in the practice during this period. The use of short-acting β2-adrenergic agonist (SABA) or short-acting muscarinic antagonist therapies did not affect inclusion into the study.

Time on maintenance monotherapy was defined from the first prescription of a LABA or a LAMA until the end of the study period (December 31, 2013) or until step up to dual/triple therapy, for example, addition of another long-acting bronchodilator, an ICS, or ICS/LABA. A minimum of four consecutive prescriptions and 6 months on continuous monotherapy were required for study entry.

Outcomes

The following disease outcomes were investigated during the monotherapy period and during the 6 months following the end of monotherapy:

- number of GP visits;

- number of exacerbations defined: 1) as addition of antibiotics and/or oral corticosteroids (within 5 days of initiation of antibiotics) to the patient’s medication and 2) by CPRD medical codes;

- number of (inpatient) hospitalizations linking to Integrated Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data;

- number of referrals, defined as consultations to the appropriate clinical specialties (respiratory medicine, geriatrics, general medicine, and accident and emergency) for COPD-related reasons.

To identify the hospitalizations due to COPD exacerbations (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems tenth revision code: J44.1), we used the integrated HES dataset. Only for this outcome, we restricted the cohort to those patients in CPRD with a linked HES record.

Covariates

The population demographics identified and described in this study included age, sex, FEV1, body mass index, and smoking history. We also investigated the presence of concomitant comorbidities at the time of COPD diagnosis, including acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart disease, atrial fibrillation, renal impairment (chronic kidney disease stages 3 through 5), cerebrovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, and peripheral vascular disease.

Within the maintenance monotherapy cohort, patients were stratified by severity categories (A, B, C, or D) as defined by the GOLD stages of airflow obstruction.13 Severity was determined by combining data from response to the Medical Research Council dyspnea questionnaire, by the number of exacerbations in the past 12 months, and by FEV1 (as % of predicted). In the absence of spirometry and/or dyspnea score, the patients’ COPD exacerbation history was considered, and all patients were categorized as having either ≤2 or >2 exacerbations within the past year and were categorized as A/B or C/D, respectively.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used for the baseline characteristics of the cohort of patients first diagnosed with COPD between 2002 and 2011, as well as for the rate of the four outcomes of interest.

Survival analysis was used for descriptive purposes to calculate the 1-year step-up rate (from monotherapy to dual or triple therapy), and a Cox proportional hazards model was used to compare the time to step up in patient subgroups (eg, male vs female patients, patients aged 50–70 vs >70 years, and GOLD severity A/B vs C/D). Patients who stayed on monotherapy or died or were transferred out of practice before December 31, 2013 were censored.

Ethics

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The CPRD group has obtained ethical approval from a National Research Ethics Service Committee and is recognized and validated by the health research authority (http://www.hra.nhs.uk/about-the-hra/our-committees/research-ethics-committees-recs/) for all purely observational research using anonymized CPRD data, namely, those studies which do not include patient involvement (which form the vast majority of CPRD studies). An Independent Scientific Advisory Committee (ISAC) is responsible for reviewing the protocols for scientific quality, but may recommend that study-specific ethical approval is sought if ethical issues arise in relation to an individual study. The present study was approved by the CPRD ISAC (protocol 14_102A). Patient consent was not required by the National Research Ethics Service Committee for this CPRD study due to anonymity of the data.

Results

Patients

By the end of 2013, there were ~3.7 million active patients within the CPRD, which is a representative sample of the total UK population (of ~60 million). We extracted the GP records of 82,652 COPD patients who were ≥50 years of age at the time of their first COPD diagnosis, of whom 70% (n=57,882) had at least one LABA code or one LAMA code at any time in their medical history (Figure 1).

Of these 57,882 patients, 13,382 (23%) were prescribed a LAMA as their first prescription and had no other concomitant prescriptions; 70% (n=9,346) of these were on a LAMA for a continuous period of 180 days or more. After excluding the patients who may not have received ≥4 prescriptions during that 180-day (or longer) time period, 8,029 LAMA monotherapy patients remained. Finally, on including only those patients who remained alive and had valid CPRD records for 6 months following the end of their monotherapy period, 6,969 LAMA patients remained. The same process was applied for LABA monotherapy, which led to 1,842 patients remaining.

Thus, a cohort of 8,811 patients with COPD (95% GOLD stage A or B) on maintenance monotherapy was identified. Basic demographics of this cohort, stratified by COPD severity, are presented in Table 1. The majority of patients were male (56%) and current smokers (63%). A high proportion of patients (5%–10%) had another comorbid disease at diagnosis of COPD, including acute myocardial infarction, history of cerebrovascular disease, congestive heart disease, atrial fibrillation, renal impairment, cancer, diabetes, and peripheral vascular disease (Table 1).

Treatments

Among the cohort of 8,811 patients with COPD (95% GOLD stage A or B) on maintenance monotherapy, 45% (n=3,947) were still on monotherapy at the last record or by the end of the study period. Of these, 3,297 (84%) were only ever on a LAMA, 49 (1%) were on a LAMA and switched to a LABA, 546 (14%) were only ever on a LABA, and 55 (1%) were on a LABA and switched to a LAMA.

For all patients, the median time on maintenance bronchodilator monotherapy was 2 years and the median time from first COPD diagnosis to first monotherapy prescription was 56 days. The median number of prescriptions during this period was 14, corresponding to the mean prescription duration of 53.4 days. The yearly rate of short-acting bronchodilator prescriptions during monotherapy was 3.9 (interquartile range, 7.1; N=8,811), most of which were SABA prescriptions.

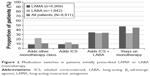

Among the 55% of COPD patients (n=4,864) who stepped up to dual or triple therapy, the treatments added on were as follows: in 11% was added the other class of monotherapy (LABA or LAMA), in 9% was added an ICS, and in 34% was added an ICS + LABA. Figure 2 identifies the proportion of patients on different combinations of COPD medications at the end of the study, while the length of time on monotherapy by the type of treatment received at the end of the study is shown in Figure 3.

Outcomes

Patients had an average of 15 health care professional (HCP) consultations per year; one in ten patients experienced a COPD exacerbation (mean: 0.1; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.1, 0.2; N=8,811) and one in 50 patients were hospitalized for COPD per year (mean: 0.02; 95% CI: 0.01, 0.02; n=4,848) (Table 2).

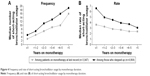

While the frequency of use of short-acting bronchodilators, measured as the total number of prescriptions collected over the years, increases with the time spent on monotherapy, as expected, the yearly rate of short-acting bronchodilator use (scripts/year) decreased with increasing time spent on monotherapy. In stratified analyses by years spent on monotherapy, we found that patients who remain on monotherapy (45%) use less short-acting medication than those who step up to dual/triple therapy at every time point (Figure 4).

| Figure 4 Frequency and rate of short-acting bronchodilator usage by monotherapy duration. |

In adjusted models, higher COPD severity (hazard ratio [HR] =1.33; 95% CI: 1.17, 1.52), higher rate of yearly short-acting medication usage (HR =1.05; 95% CI: 1.05, 1.06), and history of peripheral vascular disease (HR =1.15; 95% CI: 1.02, 1.29) all predict a statistically significant higher hazard of stepping up to dual/triple therapy. Conversely, history of diabetes (HR =0.78; 95% CI: 0.70, 0.87), rate of aspirin usage during monotherapy (HR =0.99; 95% CI: 0.98, 0.99), and female sex (HR =0.94; 95% CI: 0.89, 1.00) predict a lower hazard of stepping up.

Discussion

In this study population, we found that the median time from initial COPD diagnosis to initiation of maintenance monotherapy treatment was 56 days. The median time patients spent on maintenance monotherapy before being stepped up to dual/triple therapies was 2.1 years. During their time on maintenance monotherapy, patients demonstrated low rates of COPD exacerbations, specialist referrals, and hospitalizations. This is perhaps unsurprising, considering that due to the inclusion criteria of the study requiring patients to have been stable on monotherapy for a minimum of 6 months, majority of the study population (95%) were observed to be mild to moderate GOLD stage A+B patients. COPD patients with accelerated or more severe baseline disease would likely have been stepped up to more advanced treatment sooner and were less likely to have met the 6-month monotherapy inclusion criteria.

Conversely, it was noted that HCP interaction rates were relatively high among the monotherapy population at a mean of 15 consultations per year; though we have no comparison group in the present study, the national average GP consultation rate per patient is 5.5 per year.14 It should be noted that it was not possible to determine if these HCP interactions were primarily COPD related. We also noted that presence of diabetes was associated with longer use of monotherapy in adjusted Cox proportional hazard models, and possible explanations could include prescribers’ concerns over the effects of ICS on glycemic status.15 Aspirin use was also associated with a longer maintenance period on monotherapy. While we have no direct explanation for these observations, we could hypothesize that managing other comorbidities may detract from COPD management.

This study identified a cohort of COPD patients who were maintained on LABA or LAMA maintenance monotherapy. Overall, 45% of the study population remained on monotherapy throughout the study period and 30% had been on monotherapy maintenance treatment for over 3 years. The population that remained on monotherapy throughout the study was found to have a lower frequency of short-acting bronchodilator use than the patient population that stepped up treatment during the trial period across all time points. This could reflect better symptom control and/or lower severity of disease.

Interestingly, we observed that there was a decrease in the yearly rate of SABA use the longer the patients remained on monotherapy. This trend was observed in both the monotherapy and step-up treatment groups; however, the patients who remained on monotherapy at the end of the study demonstrated a lower rate of yearly SABA use compared to those who were stepped up in treatment across all time points. This could be due to various factors, such as patients having greater confidence in using their long-acting maintenance treatment or managing their disease over time, or conversely, it could represent worsening noncompliance for SABA use.

The 2010 NICE COPD treatment guidelines are based on patient airflow limitation and exacerbation history; however, they also allow patients to be stepped up to an ICS/LABA combination when they are deemed to be still symptomatic despite the recommended treatment, even if they have no history of exacerbations and/or mild airflow limitation.2 The current 2016 GOLD guidelines recommend the use of ICS/LABA combinations only in GOLD stage C+D patients based on exacerbation history and/or airflow limitation parameters.7 If the GOLD treatment criteria are applied to the primary care setting in the UK, it is recognized that a high proportion of GOLD stage A+B patients may have been inappropriately prescribed an ICS/LABA for maintenance treatment, which can increase their risk to ICS-associated adverse effects.7 In our study, it was observed that within 2 years of initiating treatment for COPD, ICS therapy was added to 43% of patients on LABA or LAMA monotherapy, despite the low rate of exacerbations. This may reflect inappropriate initiation of ICS as previously described and is in line with the findings from other studies.16,17

As with all studies using retrospective health information data, our study had some limitations. A record of a prescription in CPRD does not capture whether the script was dispensed or the medicine was taken by the patient, suggesting that this study was based on prescribing behavior. Other limitations include the scarcity of pulmonary function data, which can contribute to overdiagnosis, and the absence of health status data. In addition, any treatments administered outside of the primary care setting were not included in this study. The analysis used to determine the rate of hospitalizations required patients to have a linked HES record, and thus, the sample size for this analysis was limited to 55% of the total patients. Last, though this study evaluated data from patients first diagnosed with COPD between January 2002 and December 2011, treatment was assessed according to current COPD guidelines in order to maintain the relevance of the data to current practice.

Conclusion

From this study, we identified that the average monotherapy-treated patient required 15 HCP interactions per year. We also found that a large number of patients were stepped up to ICS treatment despite having no increase in exacerbations. The use of the new class of LAMA/LABA fixed-dose combinations may be a useful clinical step-up option in such monotherapy patients, prior to the use of ICS.

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH. Writing and editorial assistance was provided by Lisa Buttle, PhD, of Ascot Medical Communications Consultancy and Vidula Bhole, MD, MHSc, of Cactus Communications, which were contracted by Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH for these services. A poster entitled “Current COPD disease burden associated with maintenance monotherapy in the UK”, which included the preliminary results from this study, has been presented at the British Thoracic Society Winter Meeting, London, UK; December 3–5, 2014.

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

SE and SF are former employees of Boehringer Ingelheim Ltd., and AS, GC, and AT are currently employed by Boehringer Ingelheim Ltd. BJL has received payments for consulting and advisory boards from BI, Chiesi, Cipla, Dr Reddys, Sandoz, and Teva; support to attend educational meetings from BI, Teva, and Chiesi; and payment for talks from Meda and Teva. The Scottish Centre for Respiratory Research has received unrestricted research grant support from Teva, Chiesi, and Almirral and payment for multicenter trials from AstraZeneca, Janssen, Teva, and Roche. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

HSE. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in Great Britain in 2014. 2014. Available from: http://www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/causdis/copd/index.htm. Accessed February 5, 2016. | ||

NICE. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care. London: National Clinical Guideline Centre – acute and chronic conditions; 2010. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK65039/. Accessed February 5, 2016. | ||

WHO. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Fact Sheet 315. 2015. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs315/en/. Accessed February 5, 2016. | ||

Healthcare Commission. Clearing the Air: a National Study of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Great Britain: Commission for Healthcare Audit and Inspection; 2006. | ||

Pascoe S, Locantore N, Dransfield MT, Barnes NC, Pavord ID. Blood eosinophil counts, exacerbations, and response to the addition of inhaled fluticasone furoate to vilanterol in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a secondary analysis of data from two parallel randomised controlled trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3(6):435–442. | ||

Suissa S, Patenaude V, Lapi F, Ernst P. Inhaled corticosteroids in COPD and the risk of serious pneumonia. Thorax. 2013;68(11):1029–1036. | ||

From the global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2016; 2016. Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/. Accessed March 3, 2016. | ||

Garcia Rodriguez LA, Perez Gutthann S. Use of the UK General Practice Research Database for pharmacoepidemiology. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;45(5):419–425. | ||

Jick SS, Kaye JA, Vasilakis-Scaramozza C, et al. Validity of the General Practice Research Database. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23(5):686–689. | ||

Khan NF, Harrison SE, Rose PW. Validity of diagnostic coding within the General Practice Research Database: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60(572):e128–e136. | ||

Herrett E, Thomas SL, Schoonen WM, Smeeth L, Hall AJ. Validation and validity of diagnoses in the General Practice Research Database: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;69(1):4–14. | ||

Williams T, van Staa T, Puri S, Eaton S. Recent advances in the utility and use of the General Practice Research Database as an example of a UK primary care data resource. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2012;3(2):89–99. | ||

GOLD. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2015 update; 2015. Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report_2015.pdf. Accessed February 5, 2016. | ||

NHS. Trends in Consultation Rates in General Practice 1995 to 2008: Analysis of the QResearch Database; 2009. Available from: http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB01077/tren-cons-rate-gene-prac-95–09–95–08-rep.pdf. Accessed February 5, 2016. | ||

Faul JL, Tormey W, Tormey V, Burke C. High dose inhaled corticosteroids and dose dependent loss of diabetic control. BMJ. 1998;317(7171):1491. | ||

Wurst KE, Punekar YS, Shukla A. Treatment evolution after COPD diagnosis in the UK primary care setting. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e105296. | ||

Wurst KE, St Laurent S, Mullerova H, Davis KJ. Characteristics of patients with COPD newly prescribed a long-acting bronchodilator: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:1021–1031. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.