Back to Journals » Open Access Emergency Medicine » Volume 9

The art of removing nasal foreign bodies

Authors Ng TT , Nasserallah M

Received 31 August 2017

Accepted for publication 9 October 2017

Published 6 November 2017 Volume 2017:9 Pages 107—112

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/OAEM.S150503

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Hans-Christoph Pape

Tian-Tee Ng, Michael Nasserallah

Ear, Nose and Throat Unit, Department of Surgery, Frankston Hospital, Peninsula Health, Frankston, VIC, Australia

Objective: The removal of nasal foreign bodies (NFBs) can be a difficult task for the inexperienced physician, and the more unsuccessful attempts are made, the more difficult the extraction becomes. We have formulated this simple “four-step” approach to improve success, especially on the first try.

Methods: A retrospective review of cases requiring NFB removal, seen by one registrar from 2012 to 2016 at Frankston Hospital, was performed.

Results: From 2012 to 2016, 93 patients were referred, of whom 65 were confirmed to have NFBs. In all, 20 patients were first seen by the registrar and had the NFB removed successfully. Another 28 patients were referred to the registrar only after one failed attempt by another medical personnel, and the remaining 17 patients were referred after two failed attempts. All patients had the NFB removed locally in the emergency department using the “four-step” approach, except four patients who had the NFB removed under general anesthesia in the operating theater. Three of the latter had two failed attempts and had refused further attempts, and the fourth patient had developed epistaxis after a failed removal by his general practitioner.

Conclusion: When performed correctly, the “four-step” approach will result in the successful removal of NFBs. Ideally, the removal of NFBs should only be performed by an experienced medical personnel, and any failed first attempt removals must be subsequently managed only by an experienced medical personnel.

Keywords: nasal foreign body, removal, pediatrics

Introduction

Having been an ear, nose and throat (ENT) clinician for >10 years (TTN) and having successfully managed many patients with nasal foreign bodies (NFBs) during this time, in this study we have investigated the outcomes of patients seen by one clinician (TTN) in order to develop and describe a process to improve the success rate for NFB removal. NFB is a not an uncommon presentation to the emergency department (ED) and make up ~0.1% of pediatric ED visits.1

I (TTN) still remember my first patient with a NFB: a 5-year-old child with a bead up her nose. The process of examining and attempting to extract the NFB took more than an hour, after which the bead was still firmly in place up her nose – i.e., this was also my first failure. At this point, my consultant saw her and it took him <10 seconds to extract the NFB. We describe here his technique, distilled into four steps, which TTN thereafter learnt and used to quickly and easily remove NFBs.

Methods

All of the participants described in this study were treated by one clinician (TTN) but analysis and description of the results by both authors. In order to highlight the difference in outcome depending on the steps used to try to remove the NFBs, we have performed a retrospective review of NFB cases at Frankston Hospital from 2012 to 2016. This study was approved by the Executive Sponsor Research of Peninsula Health (protocol number: QA/16/PH/12). The ethics approval application for this study was reviewed by the Peninsula Health Research Committee, and patient consent was not required as this was deemed as an audit. Written informed consent was obtained from the guardians of the patients depicted in photographs.

Results were compiled in a spreadsheet using Microsoft Excel v14. Percentage distributions of symptoms and types of foreign bodies were calculated and presented as graphs using SigmaPlot v13.0 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). Statistical comparison was also performed using SigmaPlot v13.0.

Results

Between 2012 and 2016, a total of 93 patients were referred, of whom 28 patients proved not to have NFBs. The mean age of NFB patients was 3 years and 10 months with a standard deviation of 1 year and 11 months; the youngest was 1 year and 9 months old, and the oldest was 13 years old. Of the 65 NFB patients, 55% were females and 45% were males. Over the 5-year period of data collection, the proportions of patients who went through one, two or three extraction attempts varied significantly (by Kruskal–Wallis rank test, c2=13.2, df=4, P=0.01). However, comparing 2012 to 2016, the proportion of successful first attempts has not increased and the numbers of second and third tries are still high (Figure 1A); hence, there is a need to educate medical personnel on removing NFBs.

| Figure 1 (A) Percentage of NFBs removed after one, two or three tries: 2012–2016. (B) Proportion of symptom types. (C) Types of NFBs. Abbreviation: NFBs, nasal foreign bodies. |

Pooling the data from the 5 years studied, 61 of the 65 patients with NFBs had them removed in the ED. The remaining four patients had their NFBs removed under general anesthesia in theater. Three of this group had two failed previous attempts to remove their NFBs, and the fourth one had epistaxis after a failed first attempt by a general practitioner, and their parent refused any more attempts. Less than one-third had a successful first removal attempt. The most common group was that whose successful NFB removal was by the ENT registrar after a failed first try (Table 1).

| Table 1 Number and percentage of patients who had one, two or three attempts to remove NFBs, 2012–2016 Abbreviation: NFBs, nasal foreign bodies. |

Only 20% of NFB patients inserting a foreign body (FB) up their nose were witnessed by care givers. Slightly more (25%) were self-confessed patients, but more than half (54%) were unwitnessed. Added to that, 91% of patients presented without any discharge, and in fact, 71% were asymptomatic. For the remainder of patients, only 8% had discharge, 6% had a foul smell and a further 6% had a combination of the two. The remaining population presented in groups defined by symptoms such as obstruction, epistaxis, discharge or pain or the combined foul smell, epistaxis and pain, each of which represented<3% of the population (Figure 1B).

The NFB types could be divided into six groups (Figure 1C); two-thirds were inorganic materials of great variety, including erasers, Texta® (felt-tip marker pen) caps and plastic toys. In addition, inorganic but well represented were beads (28%). Far less common were Lego® toy pieces (9%) or button batteries (3%). In general, the organic group was composed of different food types (TicTac®, M&M®, pea, rice, meat, raisin, apple bits, popcorn, corn, seed and cereal, with the occasional piece of inedible plant such as a gumnut).

Discussion

As there was no decrease in the proportion of patients who had multiple NFB removal attempts over the 5-year period (Figure 1A) and as each failure makes subsequent attempts harder, there is clearly a need to develop and disseminate a tool to improve success on the first attempt. This would clearly reduce stress, anxiety for the patient and the patient’s family and possible trauma to the patient. As the failed first or second attempts were by another doctor/s, either general practitioner or emergency doctor (intern, resident, registrar or specialist), there also appears to be a need to either have experienced ENT personnel or emergency physician at hand or to provide this four-step process to all doctors who might reasonably expect to encounter these cases, to increase the NFB removal success rate, especially in very young pediatric cases.

More than half of the NFB patients had an unwitnessed event leading to the insertion of NFBs. However, given the average age of the patients, it is perhaps not surprising that a high proportion of patients were not observed or confessed to inserting the NFBs as they would be less likely to understand parental warning or be able to verbalize their actions. There are a number of histories in common that may arouse care givers’ suspicions regarding the likely insertion of NFBs:

- First, suspicious circumstances, i.e., where the battery compartment of toy was found opened, and one of the batteries was missing and not found.

- Second, child acting strangely, i.e., where the child keeps rubbing or picking their nose.

- Third, a broken toy with missing parts, i.e., broken bracelets and unable to find all beads.

- A trail of “evidence”, i.e., trail of colored discharge flowing out from one nostril where the child has likely stuck a fragment of a green-colored crayon.

As reported by Svider et al,2 jewelry beads were the most common NFBs found in North American pediatric patients. This corresponds to our findings (Figure 1C). However, this was not the case in studies conducted in less-developed countries. Yaroko and Baharudin3 reported that the most common NFB in Malaysia was a seed, followed by a rubber band; they also pointed out that these are the most common objects played with by children of these populations.

The 30% of patients who sought medical attention but on examination did not have NFBs and were very likely to have had NFB that were dislodged or had dissolved prior to examination by the ENT registrar. The time taken for some popular sweets to dissolve in this manner has previously been published and is surprisingly quick.4 For example, very common organic NFBs like a Tic-tac® or Smartie® dissolve within an hour.

From my experience in removing NFBs from patients presented at Frankston Hospital, it was clear that the NFBs are easiest to remove when an experienced medical personnel was the first doctor to be consulted. It gets more difficult as the number of attempts increases due to patients being traumatized and becoming more anxious by previous unsuccessful attempts. In my experience, all NFBs can be removed successfully in the first attempt by an experienced medical personnel. Thus, it would be of benefit to have a simple four-step process for all medical personnel who would be likely to extract NFBs, especially from very young pediatric patients.

There are three components involved in removing NFBs: the medical personnel, the child with NFB and the carer/parent, each of which would be either constant or variable. Ideally, we would prefer all components to be constant, as the outcomes are predictable. As a doctor, I am a constant entity, and as almost all children with NFB will have the NFB lodged between the septum and inferior turbinate, they will mostly be quite cooperative for NFB removal on the first time but will fight and scream with subsequent attempts. Hence, the child could be considered as a constant entity as their behaviors and the site of NFB could be predicted. The carer or parents are the variable in this situation as we cannot predict how cooperative the carer or parent would be in helping to restrain the child. Hence, it is important to communicate to the carer or parent how important their role is in restraining the patient to prevent trauma and successfully remove the NFBs.

The management of child with NFBs starts with history taking. A child with unilateral foul smelling nasal discharge is pathognomonic of a retained NFB. This would be followed by the “four-step approach”, which includes nasal examination and the removal of NFB.

The “four-step approach” in removing of NFBs is summarized as follows:

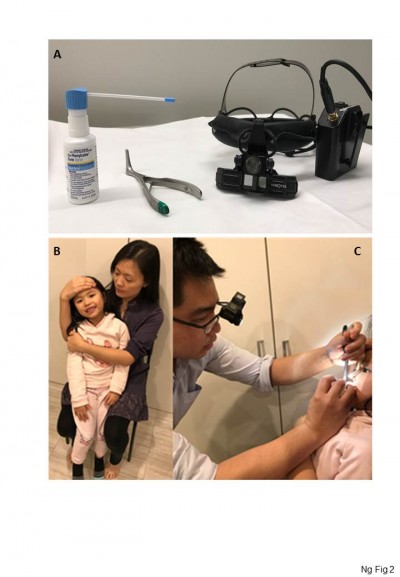

- Step 1: use a headlight (Figure 2A) to free up both hands, one to hold the nasal speculum (Figure 2A) and other to grasp the instrument of choice to remove the NFB.

- Step 2: use a nasal speculum (Killian nasal speculum; Figure 2A) to examine the patient’s nose. The speculum is crucial as NFB may be otherwise missed in those with congested turbinates.

- Step 3: spray decongestant into the nose (co-phenylcaine forte nasal spray™ [ENT Technologies Pty Ltd., Hawthorn East, VIC, Australia]; Figure 2A); this helps to anesthetize and decongest the nasal cavity.

- Step 4: ensure the child is well restrained. (Figure 2B). This is where the carer or parent plays an important role. Only proceed to remove NFB in a quiet well-restrained child (Figure 2C) because of risk of injuring the child’s nose with the instruments, which may lead to epistaxis and further distress to the patient and carer.

If having completed the “four-step approach” and examined the nasal cavity in its entirety and determined there is no NFB, the patient can be safely discharged home. Carer and parent should be advised to bring the patient back if the patient develops foul smelling nasal discharge or other nasal symptoms.

However, if the examination confirmed the presence of a NFB, now choose the instrument for NFB removal. Over the last 2–3 years, I have mainly used a metallic ring curette to remove NFBs. I find it very safe, and it can be used to remove the NFBs quickly without causing much trauma to the nasal cavity. I find the metallic ring curettes to be far superior and versatile than the disposable plastic curettes, as the plastic curettes are too thick and obscure the view and are also quite malleable and not as rigid as the metal ones. Other instruments such as suction and forceps take more time to make the correct positioning in the nasal cavity before removal of NFBs, and time is something that is scarce in a struggling child. Other noninstrumental methods in removing of NFBs such as the positive pressure method, also known as the kissing technique, although as minimally invasive only report a success rate of up to 50%, whereas I have not yet failed to remove any NFB with the four-step approach and the metallic ring curette.

I inform the carer or parent to cuddle the child tightly (Figure 2B and C) for 10 seconds as the process of extracting the NFBs usually takes less than this. With my nondominant hand holding the nasal speculum and my dominant hand holding the instrument of choice, I remove the NFBs with both hands resting on the patient’s face (Figure 2C), to minimize risk of trauma in case the patient breaks free from the cuddle. In my experience, all NFBs that can be visualized with just the nasal speculum and without the aid of magnification (i.e., without an otoscope or flexible nasolaryngoscope) can be safely removed in the ED. After removal of NFB, the nasal cavities should be reexamined to make sure there are no NFBs left. See Figure 3 for the “four-step approach” flow chart.

| Figure 3 Flow chart for the “four-step approach” in removing NFBs. Abbreviation: NFBs, nasal foreign bodies. |

Limitations

There were two primary limitations to this study – first, the study was a retrospective one and therefore we were restricted to only that information that had been acquired at the time. Second, we had no information on the number of successful NFB removals who did not present to Frankston hospital. Thus, our percentages represented not the proportion of all NFB cases but the proportion of the population presenting to Frankston Hospital. This also means that our study population was restricted to a regional level. As discussed in the article, there have been differences noted in the most common inorganic NFBs depending on the nationality of the population being studied.2,3 We believe these results still describe a common problem and confirm the need to have a simple description of the techniques and staff needed to increase the probability of success in NFB removal.

Conclusion

The removal of NFBs should only be performed by experienced medical personnel as the child with NFBs usually allows only one or two attempts. Junior doctors who wish to attempt removal should be supervised by an experienced senior colleague. All failed first attempt removals should only be managed by an experienced medical person. The art of removing NFB uses the four-step approach, which, when performed correctly, will lead to the quick, successful removal of NFBs and avoid trauma. Like everything in life, practice makes perfect; the art of removing NFBs can only be perfected with experience and practice.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Vicky Tobin and Frankston Hospital Library. This project was not financially supported from any external sources and was fully funded by the Department of Surgery, Frankston Hospital.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Kiger JR, Brenkert TE, Losek JD. Nasal foreign body removal in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24(11):785–792. | ||

Svider PF, Sheyn A, Folbe E, et al. How did that get there? A population-based analysis of nasal foreign bodies. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014;4(11):944–949. | ||

Yaroko AA, Baharudin A. Patterns of nasal foreign body in northeast Malaysia: a five-year experience. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2015;132(5):257–259. | ||

Leopard DC, Williams RG. Nasal foreign bodies: a sweet experiment. Clin Otolaryngol. 2015;40(5):420–421. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.