Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 6

Teaching pediatric communication skills to medical students

Authors Frost K, Metcalf E, Brooks R, Kinnersley P, Greenwood S, Powell C

Received 26 May 2014

Accepted for publication 14 July 2014

Published 16 January 2015 Volume 2015:6 Pages 35—43

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S68413

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Katherine A Frost,1,2 Elizabeth P Metcalf,3 Rachel Brooks,2,3 Paul Kinnersley,3 Stephen R Greenwood,3 Colin VE Powell1,2,4

1Noah’s Ark Children’s Hospital for Wales, 2Department of Pediatrics, 3Institute of Medical Education, 4Molecular and Experimental Medicine, School of Medicine, Cardiff University, Cardiff, Wales

Background: Delivering effective clinical pediatric communication skills training to undergraduate medical students is a distinct and important challenge. Pediatric-specific communication skills teaching is complex and under-researched. We report on the development of a scenario-based pediatric clinical communication skills program as well as students’ assessment of this module.

Methods: We designed a pediatric clinical communication skills program and delivered it five times during one academic year via small-group teaching. Students were asked to score the workshop in eight domains (learning objectives, complexity, interest, competencies, confidence, tutors, feedback, and discussion) using 5-point Likert scales, along with free text comments that were grouped and analyzed thematically, identifying both the strengths of the workshop and changes suggested to improve future delivery.

Results: Two hundred and twenty-one of 275 (80%) student feedback forms were returned. Ninety-six percent of students' comments were positive or very positive, highlighting themes such as the timing of teaching, relevance, group sizes, and the use of actors, tutors, and clinical scenarios.

Conclusion: Scenario-based teaching of clinical communication skills is positively received by students. Studies need to demonstrate an impact on practice, performance, development, and sustainability of communications training.

Keywords: communication training, undergraduates, pediatrics, actors

Two Letters to the Editor has been received and published for this article

Patel and El Tokhy

Bhatti and Ahmed

Introduction

It is well recognized that communicating with children and their families can be challenging for health professionals. A survey of young patients by the Health Commission in 2004 suggested that many children are unhappy with the way in which health workers relate to them whilst they are in hospital.1 Equipping undergraduate students with the tools for effective communication via specific teaching whilst on clinical placement should therefore be part of the curriculum at all universities. Good clinical communication skills correlate with improved health care outcomes.2–4 The recognition that communication skills are a basic clinical skill and the development of practical teaching tools such as the Calgary-Cambridge Guide to the Medical Interview5,6 have led to an improvement in communication skills teaching.7 Draper’s work has been centered on consultations with an adult patient. Although several projects have addressed pediatric trainees’ communication skills,8,9 there is limited work exploring undergraduate level teaching that is focused on the distinct complexities of communicating with children and their families, particularly the challenges of a three-way consultation between a child, their parent, and the doctor.10–14

At Cardiff University, as at other UK medical schools, there is an expectation that undergraduates will finish their pediatric clinical placement with appropriate communication skills. We test this in an Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE)15 at the end of the 5-week placement. Learning good communication skills requires an understanding of the key skills and an opportunity to practice these skills. This practice should be done within a setting where mistakes may be made with no ill effect on patients and from which students can receive personalized feedback on their performance. Using actors has an advantage over using patients as actors may reliably reproduce roles, can consistently portray difficult emotions, and may offer feedback.2,14–17 To allow students to practice communication skills in the pediatrics context, workshops were designed with actors. The aims of this report are to describe the development of a compulsory module for fourth year undergraduate students focusing on the key issues of communicating with children and families, and to assess this module in terms of students’ perceptions of their experience.

Materials and methods

Program design

At the Cardiff University School of Medicine, students are taught clinical communication skills from their first year. Generic communication skills teaching focuses upon students developing an understanding of the basic principles of effective communication, an ability to consider both content and process in effective communication, giving and receiving feedback, and in setting personal learning agendas. The curriculum ensures that the students meet gradually increasing challenges as their clinical skills develop.

The learning outcomes for the pediatrics session were built upon the previous teaching sessions, with the addition of increased emphasis on the need to consider both the child and their family, the emotional impact of the illness within the consultation, and how skilled communication can improve children’s and families’ experience of that illness (see Figure 1).

| Figure 1 Intended learning outcomes. |

Developing and delivering the module

A group of general practitioners with training in effective communication worked closely with pediatricians to identify the challenges of communicating with children. Using these as the foundation, we developed a teaching program, run initially as a pilot scheme, to ensure that students were well equipped to communicate with children during their pediatric ward placement. We did not formally conduct a needs assessment, but whilst we assess students on their pediatric communication skills, we were not formally teaching them. We designed the program using the Calgary-Cambridge guide5 as a foundation. This model provides a clear framework of skills for a generic consultation and highlights the need to address both the disease (the biomedical problem) and the illness (the patient’s experience) within the consultation. Five components of a consultation are recognized (ie, initiating the session, gathering information, physical examination, explanation, and closing the session), as are encouraging fluidity and a structured approach.5 Our teaching session allows students to observe an example of communication with a child or family, using a video recording, then having the chance to practice and develop their own communication skills. Time was also taken to discuss the individual student’s learning agenda, with the aim that feedback can be tailored appropriately to best meet individual learning needs.

During the 2012–2013 academic year, we delivered five sessions, teaching six groups of approximately ten students each time. Two tutors, a general practitioner and a pediatrician, taught each group. This balance of experience offers students teaching in effective communication together with expertise in pediatric practice.

The duration of the teaching session delivered during the introductory week of classroom teaching, prior to students moving out across Wales on clinical placements, was two and a half hours (Figure 2). A video of a three-way consultation between a doctor, an 8-year-old girl with a chronic history of headaches, and her mother was used as a focus for discussion. Tutors are encouraged to stop and start the video, allowing students to raise points that they want to explore.

| Figure 2 Lesson plan. |

Three scenarios of 30 minutes each followed the video (outlined in Figure 3). Simulated patients/parents (actors) were given a detailed clinical scenario, including possible responses and questions they might use. Tutors received the scenario along with a list of key skills to be focused upon for each consultation, having completed a “train the trainers” day previously. Students received a shorter introduction to each scenario in workbooks, which were available from the start of the academic year on the intranet and distributed as a hard copy to each student on the day before the teaching session. The students were encouraged to read the scenarios and familiarize themselves with their content prior to the session. The workbook includes suggested resources from which they can read about the clinical issues arising for each scenario in advance. Students were encouraged to volunteer to interact with the actors, and were reassured that the tutors would pause the scenarios after a few minutes in order to analyze the content and generate discussion. So that each student had a chance to consult, the scenarios were structured in two parts, allowing one student to take the first part and receive feedback, before a second student swapped into the role of the doctor. The final 30 minutes of the workshop were allocated to summarizing the session and addressing points raised by the students, directing them to resources and learning opportunities on future clinical placements.

During the workshops, we used agenda-led outcome-based analysis18 which is designed to focus feedback on the learner’s needs or agenda. Following a consultation with the simulated patient, the student was first encouraged to reflect upon their own performance using a domain-centered, self-assessment rating sheet as a guide (Table S1). This was separate from the Likert-scale tool used for assessment of the overall session (see below). Feedback was then given by their tutors and peers, with the simulated patient giving the perspective of the patient. After consulting, students were asked if they felt their feedback agenda had changed, and feedback was focused appropriately by the tutors using the Calgary-Cambridge model. Each student was encouraged to discuss their consultation experience with input from the rest of the group.

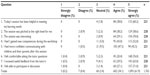

Student assessment of the module

In order to assess the teaching, students were asked to complete an anonymous feedback form before leaving the session. This form explored eight domains: learning objectives, complexity, interest, competencies, confidence, tutors, feedback, and discussion (Table 1). Each question was scored using a Likert scale from 1 to 5 (1, strongly disagree; 5, strongly agree). In addition to scoring each question, the students were encouraged to give written free text feedback. Two separate analyses were then performed: KF collated the scores for each question, and a thematic content analysis, using a coding scheme developed by SG, was performed on the free text data. RB, CP, and KF reached the consensus that several themes could be identified, ie, the timing of teaching, its relevance, group sizes, the use of actors, tutors, clinical scenario, feedback, and environment. A method of scoring the comments was then devised and agreed upon, and KF analyzed the comments. Each was scored between 1 and 4, as detailed in Table 2.

| Table 1 Questions asked of students, with their response to a 5-point Likert scale |

Results

Quantitative data

Of the 275 students invited to attend teaching during the 2012–2013 academic year, 221 (80%) returned feedback forms, although some were incomplete. Overall, 96% of respondents said they agreed or strongly agreed with the statements (Table 1). Students strongly agreed that the sessions were interesting (70%) and helpful (60%), and that they felt comfortable both asking the tutors questions (76%) and participating (71%). Lower proportions strongly agreed that they had gained new competencies (52%) or that they felt more confident communicating with children and their parents after the session (43%). The proportion of students disagreeing or strongly disagreeing with all the positively worded statements was very small.

Qualitative data

Table 2 shows the numbers of comments made by students and classified by the researchers according to theme, and their level of critique as highlighted in the key. The great majority of comments (181/266, 68%) were coded as positive (scoring 3 or 4). The themes receiving the highest proportion of positive comments were tutors and feedback. Group size was the only theme to receive more negative than positive comments, and comments on the use of actors were evenly divided between positive and negative. To understand more about the themes, particularly those that received fewer unanimous comments, an analysis of specific comments was undertaken and is presented here grouped under the themes.

Timing and relevance of teaching

The majority of students commenting felt the workshop was more useful before their placement:

I enjoyed this teaching and feel more confident now with the prospect of dealing with difficult situations while on my pediatric placement.

However, several were concerned about their own lack of pediatric knowledge:

May be more useful at the end of the block when we’ve seen and witnessed some of the situations.

Clinical scenarios and use of actors

Approximately 50% of the students commenting were very positive about the use of actors:

The actors were really good, made the consultations feel realistic.

However, several students commented that it would have been better to have children in the role:

Very good but would be much better at developing our communication skills with children if we had children to practice with.

Some found the scenarios challenging and felt ill-prepared, particularly for the confrontation with a father in the safeguarding scenario (scenario 3). In general though, whilst students found the scenarios challenging, they felt that it was good to explore issues such as safeguarding within a teaching session:

Good to deal with difficult situations and that everyone had an opportunity to take part.

I liked the more challenging scenarios as it gave us an opportunity to come up with ideas/methods to deal with such cases in real practice.

Some students also expressed a view that the difficult scenarios were helpful but took up time that they would rather have used in preparation for their assessments:

It was useful to have such a confrontational consultation and to deal with child protection. However, this was not relevant to things I would have to deal with as a fourth year and I feel this was to the detriment of me having experience of what I will be expected to do in my OSCEs.

Environment, group sizes, tutors, and feedback

Students consistently suggested that smaller student groups would enable more effective learning:

Maybe smaller groups/more actors so everyone gets a chance to do a full consultation.

Some, however, felt that the group size allowed them to learn from one another:

Nice to have a big group allowing you to pick up tips from other people,

Very useful to see others do scenarios and have a go too.

In general, students felt the teaching environment was friendly and relaxed and that they had a good chance to practice their communication skills comfortably:

It was great to practice the skills in a non-threatening environment.

Relaxed atmosphere, which helped when it came to consulting. Didn’t feel pressure to do it perfectly.

Students’ comments were unanimous that the tutors were supportive and encouraging, providing feedback to the students and guiding them as to the additional skills that they could use in future consultations. Opinion was split between wanting feedback straight away or at the end:

Tutors made it easy to voice opinions and discuss each topic.

Tutors were positive with feedback and helpful at directing the consultations.

The feedback was always constructive and has helped me change how I’ll interact with patients.

It was very useful to receive feedback immediately.

Would have been better to have fewer interruptions during each scenario and feedback at the end.

Some commented on aspects such as enjoying hearing anecdotes of working life and sharing tutors’ experiences:

Good to hear doctors’ life experiences.

Tutors were really helpful and added a lot to the experience.

Discussion

Our teaching program has received very good feedback from students and addresses important learning outcomes. It builds upon skills learnt during students’ earlier undergraduate years at Cardiff University using a spiral curriculum and develops these skills in the context of pediatric patients, resulting in a patient-centered approach to communication. Teaching and feedback are linked to each student’s individual learning needs.

Overall, students perceived this workshop module positively. As highlighted in the results section, quantitative data analysis showed that 96% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statements used for assessment of the program. Qualitative analysis demonstrates that the majority of free text comments left by students were positive (68%). It is reassuring that the qualitative analysis appears to agree with the quantitative survey data, where the highest proportion of “strongly agree” scores went to questions including “I felt comfortable asking the tutor questions”, “I felt able to participate in discussion”, and “I received useful feedback from the tutor(s).”

When developing a teaching program, it is important that the environment and teaching style are supportive of creating a safe and secure session during which students can practice their communication without fear of criticism, since it is known that academic performance and self-efficacy are to some extent interrelated.19–21 In this program, students strongly agreed that they felt comfortable both asking the tutor questions (76%) and participating (71%).

Students were divided on whether the use of actors was positive or negative, with some commenting that they would rather work with real patients and children than actors. However, child employment laws state that children cannot be employed within school hours and there are stringent definitions of what is suitable employment.22 These laws have made it necessary to use actors and actresses in the scenarios used in teaching (though the 8-year-old girl filmed for the example of a consultation was the daughter of an actress and filmed her part within the school holidays). Nonetheless, working with actors does have the advantage that we can provide students with challenges, for example, about a child abuse consultation, which they would not be able to experience in a teaching session with real patients.

The majority of comments relating to group size were negative, with many reflecting the students’ desire for smaller group sizes, enabling them to have more chance to consult. As a result, group sizes were reduced for 2013–2014. Many suggested that they would like to be able to take scenarios further and have more discussion, recognizing that the workshop is aimed at introducing the challenges of pediatric communication that students will build upon whilst on clinical placement.

We acknowledge, however, that the type of feedback that we have collated recognizes only the students’ reactions to the teaching, ie, a Kirkpatrick level one evaluation.23 More optimally, one would attempt to obtain measures of impact beyond this, such as assessing student learning (level 2) or observing their subsequent communication behaviors (level 3) on the placement. The feedback has, however, allowed us to discover strengths and weaknesses of the workshop and identify areas that need improvement.

We will continue to assess this teaching program, particularly considering the design changes made as a result of the initial evaluation. There are students who attend with pre-existing experience and confidence in communicating with children and families. Development of future modules could focus on individual student expectations and learning needs, as this may enable them to improve their confidence and gain new competencies. We realize that students tend to reflect positively immediately at the end of a session. It is hoped that for future sessions we may ask for feedback at the end of the clinical placement so as to assess the impact that the teaching had on each student’s skills and clinical experience.

In time, we hope that the sessions will be exclusively taught by paediatricians. Tutor training sessions will be delivered by general practitioner communication skills tutors, highlighting the principles of the course and its objectives. Pediatricians have also been encouraged to use an e-learning package developed by the UK Clinical Communication in Undergraduate Medical Education, which students also have access to through the Cardiff University website.

Conclusion

This teaching session worked well as a pilot scheme and has been positively received during its first year. It is now a recognized part of the undergraduate pediatric curriculum in Cardiff and will be taught to all future years of students. This small-scale study has shown how a pediatric communication skills module can be developed and evaluated using standardized tools and a structured approach. It should be replicable in other centers and also transferable to different stages in undergraduate and postgraduate curricula, given that it would be the complexity of challenges presented and not the structure that would need to be varied.

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to all the students who took part in the sessions and for the skills of the actors who took on the roles of parents and young adults in the scenarios.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Healthcare Commission. Healthcare Commission Patient Survey Report 2004 – young patients. 2004. Available from: http://www.nhssurveys.org/Filestore/CQC/YP_KF_2004.pdf. Accessed October 25, 2014. | |

Rider EA, Hinrichs MM, Lown BA. A model for communication skills assessment across the undergraduate curriculum. Med Teach. 2006;28(5):e127–e134. | |

Stewart MA, Brown JB, Weston WW, McWhinney IR, McWilliam CR, Freeman TR. Patient-Centered Medicine. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage; 1995. | |

Stewart MA, Brown JB, Boon H, Galajda J, Meredith L, Sangster M. Evidence on patient-doctor communication. Cancer Prev Control. 1999;3(1):25–30. | |

Kurtz SM, Silverman JD. The Calgary Cambridge Referenced Observation Guides: an aid to defining the curriculum and organizing the teaching in communication training programmes. Med Educ. 1996;30(2):83–89. | |

Kurtz S, Silverman J, Benson J, Draper J. Marrying content and process in clinical method teaching: enhancing the Calgary-Cambridge guides. Acad Med. 2003;78(8):802–809. | |

Draper J, Silverman J, Hibble A, Berrington RM, Kurtz SM. The East Anglia Deanery Communication skills teaching project – six years on. Med Teach. 2002;24(3):294–298. | |

Keir A, Wilkinson D. Communication skills training in pediatrics. J Paediatr Child Health. 2013;49:624–628. | |

Gough JK, Frydenberg AR, Donath SK, Marks MM. Simulated parents: developing pediatric trainees’ skills in giving bad news. J Paediatr Child Health. 2009;45(3):133–138. | |

Paul S, Dawson KP, Lanphear JH, Cheema MY. Video recording feedback: a feasible and effective approach to teaching history taking and physical examination skills in undergraduate pediatric medicine. Med Educ. 1998;32(3):332–336. | |

Crossley J, Eiser C, Davies H. Children and their parents assessing the doctor-patient interaction: a rating system for doctors’ communication skills. Med Educ. 2005;39(8):820–828. | |

Crossley J, Davies H. Doctors’ consultations with children and their parents: a model of competencies, outcomes and confounding influences. Med Educ. 2005;39(8):807–819. | |

Bosse HM, Schultz JH, Nickel M, et al. The effect of using standardized patients or peer role play on ratings of undergraduate communication training: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Counsel. 2012;87(3):300–306. | |

Bosse HM, Nickel M, Huwendiek S, Junger J, Schiltz JH, Nikendei C. Peer role-play and standardized patients in communication training: a comparative study on the student perspective on acceptability, realism, and perceived effect. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10(1):27. | |

Boursicot KAM, Roberts TE, Burdick WP. Structured assessments of clinical competence. In: Swanwick T, editor. Understanding Medical Education: Evidence, Theory and Practice. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. | |

Haq C, Steele DJ, Marchand L, Seibert C, Brody D. Integrating the art and science of medical practice: innovations in teaching medical communication skills. Fam Med. 2004;36(Suppl 1):S43–S50. | |

Howells RJ, Davies HA, Silverman JD. Teaching and learning consultation skills for pediatric practice. Arch Dis Childhood. 2006;91(4):367–370. | |

Kurtz S, Silverman J, Draper J. Teaching and Learning Communication Skills in Medicine. Oxford, UK: Radcliffe Medical Press; 2005. | |

Bandura A. Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive-development and functioning. Educ Psychol. 1993;28(2):117–148. | |

Hansford BC, Hattie JA. The relationship between self and achievement performance-measures. Rev Educ Res. 1982;52(1):123–142. | |

Hutchinson L. ABC of learning and teaching in medicine – educational environment. BMJ. 2003;326:810–812. | |

UK Government. Child employment: restrictions on child employment. 2013. Available from: http://www.gov.uk/child-employment/restrictions-on-child-employment. Accessed January 16, 2014. | |

Kirkpatrick D. Techniques for evaluating training programs. Train Dev J. 1996;50(1):54–59. |

Supplementary materials

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.