Back to Journals » Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology » Volume 16

Surgical Treatment for Benign Lymphangioendothelioma After Two Incomplete Excisions: A Case Report and Literature Review

Authors Lu W , Cao Y, Zeng F, Chen C, Yang Z , Qi Z, Yang X

Received 19 June 2023

Accepted for publication 10 September 2023

Published 28 September 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 2697—2719

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CCID.S420019

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Jeffrey Weinberg

Wei Lu,1 Yan Cao,2 Fanhua Zeng,1,3 Chun Chen,1,4 Zhenyu Yang,1 Zuoliang Qi,1 Xiaonan Yang1

1The Department of Hemangioma and Vascular Malformation, Plastic Surgery Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS) and Peking Union Medical College (PUMC), Beijing, People’s Republic of China; 2The Department of Pathology, Plastic Surgery Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS) and Peking Union Medical College (PUMC), Beijing, People’s Republic of China; 3The Department of Burn and Plastic Surgery, Hengyang No.1 People’s Hospital, Hunan, People’s Republic of China; 4E.N.T. Department, Shenzhen Longgang District Third People’s Hospital, Guangdong, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Xiaonan Yang, The Department of Hemangioma and Vascular Malformation, Plastic Surgery Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS) and Peking Union Medical College (PUMC), Beijing, 100144, Tel +86 18810601889, Fax +86 01088964614, Email [email protected]

Abstract: Benign lymphangioendothelioma (BL) is a rare, poorly identified, slow-growing benign vascular lesion characterized by asymptomatic, solitary, well-demarcated macules, or by mildly infiltrated plaque. We report a case of an atypical BL that arose as a tender, protuberant, flesh-colored mass with cyanotic vesicles, and then progressed to a persistent exudative wound after two incomplete excisions. The patient was also diagnosed with thoracic duct narrowing. Although the stenosis was removed by surgery, the right lower extremity ulceration and exudation did not improve. Thus, we performed a thorough excision and split-thickness skin graft transplant following vacuum sealing drainage, and eventually the patient had a favorable functional and cosmetic outcome. A biopsy revealed irregular, dilated vascular spaces lined with a single layer of flat endothelial cells extending from the superficial dermis to the subcutis that did not reach the striated muscles. Additionally, by reviewing the literature on BL, in this paper we summarize the diverse pathogenic, morphological, and immunohistochemical presentations for this rare disease, as well as the histopathological differential diagnosis of lymphangiomatosis, Kaposi’s sarcoma, and angiosarcoma.

Keywords: acquired progressive lymphangioma, angiosarcoma, benign lymphangioendothelioma, Kaposi’s sarcoma, lymphangioma, lymphangiomatosis

Introduction

Benign lymphangioendothelioma (BL) is a rare, slow-growing vascular lesion that is poorly understood. It was first reported by Wilson Jones1 as malignant angioendothelioma in a 10-year-old girl and was later recognized as a benign condition and formally named “acquired progressive lymphangioma” (APL) in 1976.2 BL is characterized histologically as an uncommon lymphatic vascular proliferation with infiltrating lymphatic channels dissecting collagen.3,4 Clinically, BL lesions typically present as asymptomatic, solitary, well-demarcated macules or mildly infiltrated plaques that are pink to red-brown in color.5 According to the PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus databases, only 83 cases of BL (in 40 reports) have been described in English from 1963 to the present, with only a minority of cases experiencing relapse.6–8 Although BL is considered a rare presentation of lymphatic malformation rather than a true neoplasm, complete excision is necessary due to the infiltrating character of the entity.9

In this report, we describe a patient with BL on the lower leg who presented with multiple ulcers and exudation, and was successfully treated with a skin graft following debridement and vacuum sealing drainage. This case report has been reported in line with the SCARE 2020 Criteria.10 The patient provided consent for the publication of case details and images. Furthermore, we conducted a review of the literature to discuss the pathogenesis, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, and treatment options for BL.

Case Report

Patient Information

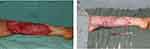

A 25-year-old female with no history of radiation exposure presented with persistent ulceration and exudation on her right lower extremity. The condition had developed three years prior following a cutaneous lesion that had been gradually growing for seven years. At age 16, the patient sustained an injury to her right calf in a bicycle accident, resulting in the development of a 3 cm x 3 cm bruise. Over time, the bruise grew into a flesh-colored, slightly tender, protuberant mass measuring 20 cm x 35 cm with cyanotic vesicles (Figure 1). Magnetic resonance imaging showed increased signal density corresponding to the vascular lesion, extending to the superficial layer of the deep fascia. In 2018, the lesion was excised and histopathological examination revealed the presence of many irregularly shaped and anastomosing channels lined by flattened endothelial cells that had infiltrated between collagen bundles through the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Atypical endothelial cells were absent. The endothelial cells expressed podoplanin (D2-40), CD31, and CD34, indicating the lymphatic nature of the lesion. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of BL or lymphangiomatosis was considered. In 2019, the patient’s wound was seeping and steadily worsening. An ultrasound revealed that the posterior lateral region of the left cervicothoracic duct was restricted. Lymphoscintigraphy showed activity in the left jugular venous angle and increased radiopharmaceutical kinetics in the right lower limb, suggesting thoracic duct outlet obstruction and lower limb lymphangioma. In May 2021, the patient underwent debridement of the lower leg, as well as recanalization and anastomosis of the chest catheter. Pathological examination suggested the possibility of hemangioendothelioma or a generalized lymphangioma. Despite the treatment, the wound on the right calf did not heal, and the patient visited our clinic for further treatment. She had been unable to walk for a year due to severe pain. The timeline of the reported incident is depicted in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Timeline of Events |

|

Figure 1 The condition of the patient’s lower limb before the first debridement. |

Clinical Findings

On physical examination, a hyperpigmented, slightly indurated, 14 cm × 21 cm mass with a strong odor was observed. There were also blisters, ulcerations, continuous seeping of lymph-like clear liquid, and some bleeding (Figure 2). The ulcerations were 3 cm × 4 cm and 3 cm × 5 cm.

|

Figure 2 The lesion of the right lower leg after two debridements at admission. Multiple ulcers and a superficial scar were visible on the dorsal area of the right calf. |

Diagnostic Approach

A wound secretion and drug sensitivity test revealed an Enterobacter cloacae infection, which was found to be sensitive to gentamicin. No abnormalities were observed upon general examination. T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging showed scattered lesions with increased signal density.

Therapeutic Intervention

After two weeks of dressing changes for preoperative preparation, the patient was admitted to the hospital. On the first day of hospitalization, the patient underwent debridement of the right lower leg under general anesthesia to remove the lesion by excising the skin and subcutaneous tissue. During the operation, lymph-like fluid was observed oozing from the unhealthy subcutaneous adipose tissue surrounding the wound. Therefore, the excision of unhealthy adipose tissue was extended to 2 cm around the lesion until healthy fat was exposed. The 18 cm × 28 cm incision was then cleaned (Figure 3A), two vacuum sealing drainage (VSD) sponges were placed on the wound, and two semipermeable membranes were used to seal the wound before applying negative pressure (Figure 3B). Continuous negative pressure of approximately 20 kPa was applied to the wound on the right lower limb after the first debridement. Closed irrigation with sterile normal saline was then performed, and the amounts of irrigation and extraction were carefully recorded (Table 2). One week after admission, the patient underwent a second procedure in which the VSD sponges were replaced under intravenous anesthesia. During this procedure, any unhealthy subcutaneous adipose tissue and exudation surrounding the wound were also removed. The VSD was left in place for an additional week. Initially, the extraction volume was greater than the rinsing volume, exceeding it by approximately 15% (104 mL) during the first ten days after the second procedure. Over time, however, the excess volume decreased to about 5% (36 mL), and the appearance of the extracted fluid gradually changed from cloudy to transparent. Two weeks after admission, the patient received an 18 cm × 28 cm split-thickness skin graft (STSG), harvested from the right thigh, to cover the wound on the right calf (Figure 4).

|

Table 2 The Intake and Output Volume of Closed Irrigation During Two VSD Treatment |

The histopathological examination of the lesions, in conjunction with the patient’s medical history, confirmed the diagnosis of BL. Microscopic analysis revealed irregular, dilated vascular spaces lined with a single layer of flat endothelial cells, which showed no signs of nuclear atypia or mitotic activity (Figure 5). The narrow vascular spaces within the dermis were separated by reticular dermal collagen bundles (Figure 6). The lesions extended from the superficial dermis to the subcutis but did not involve the striated muscles. There were no signs of extravasated red cells, hemosiderin, or inflammatory infiltrate.

|

Figure 6 The narrow vascular spaces separated by reticular dermal collagen bundles in the dermis. (Hematoxylin-eosin stain; original magnifications: B, × 4). |

Follow-Up and Outcome

The patient showed excellent postoperative recovery, and during the 1-year follow-up conducted remotely via video, complete wound healing was observed with no associated complications or recurrence. The patient expressed satisfaction with the functional and cosmetic outcome.

Discussion

The authors conducted a comprehensive search of the published literature in three databases, PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus, using restricted language to English and a specific time period up to October 1, 2022. We used appropriate search keys to identify papers related to the subject of “acquired progressive lymphangioma” and “lymphangioendothelioma”. After reviewing the titles and abstracts of 86 relevant papers, the authors found 37 articles reporting 80 cases. We also searched cited cases prior to the official recognition of the terms “APL” and “BL” and identified a total of 83 patients in 40 reports (Table 3), including 27 cases diagnosed with BL after radiotherapy for breast carcinoma.6,7,11,12 Recurrences were observed only in cases with incomplete excision,6,8,12 with only one lesion progressing to an angiosarcoma eight years later.12

|

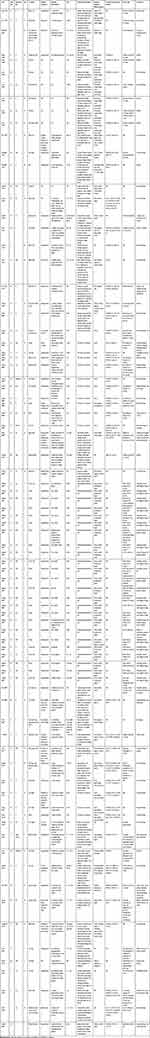

Table 3 Characteristics and Treatments of Patients with Lymphangioendothelioma Reported from 1963 to 2022 |

The etiology of this benign lymphatic malformation remains unclear, but various triggering factors have been reported, including trauma,9,13,14 tick bites,15 surgery,16–18 femoral arteriography,19 cardiac catheter examination,20 radiation therapy6,7,11,12 and recurrent cellulitis.21 Our case adds to the evidence that trauma may be a predisposing factor for the development of BL. Additionally, there have been reports of BL developing from preexisting congenital vascular lesions.8,13,20–23 Kato et al19 proposed that traumatic obstruction of lymphatic circulation, if not sufficient to induce lymphedema, could lead to lymphatic proliferation and the formation of BL lesions. Inflammatory stimuli played a critical part in the genesis and rapid growth of BL, as demonstrated by the fact that the tumor may regress gradually with topical24 or systemic9,13 corticosteroid therapy. However, the role of inflammatory stimuli is controversial, with some studies suggesting that corticosteroid therapy is ineffective,21 and spontaneous recovery of the lesion has been reported in some cases.5,25 The role of immunity in the pathogenesis of BL is crucial, as Hunt et al26 reported that the plaque grew significantly under an immunosuppressive regimen of tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. However, the response of different lesions to imiquimod, an immune response modifier, is perplexing.27,28 Another hypothesis regarding BL’s pathogenesis suggests that it may be a hamartoma of intermediately differentiated lymphatic vessels, blood vessels, and smooth muscle, given that lymphatic endothelial markers, various blood endothelial markers, type IV collagen, and desmin have been found to surround the vascular channels in many BL cases.29 In terms of the nature of BL, it is widely accepted that BL is a lymphatic vascular malformation rather than a true neoplasm, as demonstrated by the absence of WT-123,30,31 and D2-40 expression18,23,32–34 in endothelial cells. In the present case, positive D2-40 expression in endothelial cells further supports this view. Since the majority of evidence indicates that BL is a lymphatic malformation, sirolimus, which inhibits the incidence and progression of BL by targeting VEGFR-3, has been used to treat BL and has achieved satisfactory outcomes.26 However, some cases of BL with lesions larger than 60 cm have shown positive WT-1 expression,34,35 a marker of proliferation and neoplasia rather than a malformation, indicating that BL may develop a proliferative capacity in the slow enlargement process.

Jones3 summarized five features of BL that distinguish it from malignant angioendothelioma: (1) its development primarily in young individuals; (2) its sites of predilection are not limited to the face and scalp; (3) its lesion is usually localized and flat; (4) it has a slow growth and favorable prognosis; and (5) its so-called dissection of collagen appearance, channeled with a row of endothelial cells showing no obvious cellular atypicality. Of the 83 cases we found reported in the literature, most fulfill all but the first criterion. BL has been identified in virtually every age group, with the reported age of presentation ranging between 1 and 90 years, with a median age of 46.07 (the average time to diagnosis is around 6 years). It displays no sex predilection. The most commonly affected sites are the limbs (30% of cases), followed by the breast (24% of cases), head and neck (12% of cases), and other areas such as the abdominal wall, chest, back, shoulder, buttock, axilla, and groin. In contrast to most previous cases with localized, flat lesions, our patient had a slightly tender, protuberant, flesh-colored mass with cyanotic vesicles. BL criteria should allow for morphological variability, with some cases presenting as nodular mass,30 actinic keratosis-like lesion,36 condyloma acuminatum,14 and even without a visible mass or rash.25 BL can grow to a large size, with a maximum diameter of 65 cm reported in one case.35 Patients are generally asymptomatic, but occasionally, pain (sometimes extreme13), pruritus, swelling, and tenderness have been reported. Our patient experienced consistent watery clear liquid exudation after debridement, which is a symptom that has been observed in several other cases.14,18,23,30 The lymph-like fluid in our case may have seeped from ulceration, potentially exacerbating the infection. On a histological level, BL is characterized by the irregular proliferation of thin-walled vascular channels dissecting between bundles of dermal collagen. These findings can be limited to the papillary dermis but may extend into deeper subcutaneous tissue. Vascular channels are lined by a monolayer of endothelial cells, with no mitotic figures and nuclear pleomorphism. As shown in Table 3, significant quantities of endothelial cells were only observed in eight of the 83 cases.6,7,37 Usually, extravasated red cells and hemosiderin deposition, as well as marked inflammation, are rarely observed, indicating a predominant involvement of lymphatic channels. This is further supported by positive immunohistochemistry for lymphatic-specific markers such as D2-40. Results of immunohistochemistry for other lymphatic or vascular endothelium markers such as Factor VIII (F-VIII-RA), Ulex europaeus agglutinin I (UEA-I), CD 31, CD 34, LYVE-1, and PROX-1 were inconsistent (Table 3), although some studies suggest that BL may be differentiated from other lymphatic skin tumors by negative staining for F-VIII-RA and strong staining for UEA-I.21 All evidence suggests that BL is a heterogeneous disease. It is more of a pathological diagnosis than a clinical one, and we should allow for more etiological, morphological, and immunohistochemical diversity in the identification of BL.

BL is a rare lymphatic vascular proliferation that can be mistaken for various benign and malignant conditions arising from vessels. In this case report, the patient had previously been diagnosed with hemangioendothelioma, lymphangiomatosis, and BL. Upon the review of histopathology slides, the differential diagnoses included well-differentiated cutaneous angiosarcoma, hemangioendothelioma, lymphangiomatosis, and Kaposi’s sarcoma in the patch stage. Lymphangiomatosis is a rare disorder that is characterized by multifocal lymphangioma involving multiple organs such as the skin, superficial soft tissue, and abdominal and thoracic viscera in 75% of cases. In the remaining 25% of cases, it presents as diffused pulmonary lymphangioma (DPL).38 Compared to BL, lymphangiomatosis is mainly observed in children and is rarely diagnosed in patients over the age of 20, with over 75% of cases presenting with multiple bone lesions. In the case discussed in this report, the patient, who was 25 years old, experienced a progressive lower extremity lesion after previous trauma that did not reach the bone, indicating a diagnosis of BL rather than lymphangiomatosis. A definitive diagnosis of lymphangioendothelioma requires histopathological examination to distinguish it from other forms of lymphangioma, which usually show superficially dilated vascular spaces that become progressively smaller with deep extension.5,31,39 Lymphangiomatosis shares similar histological features with the deep portions of BL, characterized by a single layer of flattened endothelium that ramifies in the soft tissue.40 Considering portions of BL are virtually indistinguishable from lymphangiomatosis, Guillou et al8 believed that BL may be considered a localized form of lymphangiomatosis, and the distinction between the two is best made based on presentation and pathological extent. In lymphangiomatosis, as opposed to BL, the dilated lymphatic spaces involve not only the dermis but also the subcutaneous tissue and, occasionally, the underlying fascia and skeletal muscle.40 In the present case, the mass spread beneath the dermis and invaded subcutaneous fat but did not reach the striated muscles. Based on the clinical manifestations and infiltration depth of the lesion, a diagnosis of BL was preferred over lymphangiomatosis, even though it might be a multifocal disease.

Kaposi’s sarcoma in patch stage, which shares a red-violaceous macular appearance and lymphangioma-like cell dissection of collagen with BL, can be identified histologically by the presence of erythrocytes and spindle cells, hemosiderin deposits, plasma cells, and positive anti-HHV8 immunostaining.15,41 Differential diagnosis from well-differentiated angiosarcoma is particularly important as BL shares the histopathological presence of extensive dissection of collagen bundles with angiosarcoma. Angiosarcoma may clinically manifest as red-blue nodules or plaques that can ulcerate in the face or scalp of elderly individuals or lymphedematous extremities. BL differs from angiosarcoma in its lack of anastomosing and infiltrating vascular structures, mitosis, prominent nuclear pleomorphism or mitotic figures, and Ki-67 amplification in less-differentiated areas.7,13,42 Yamada et al7 demonstrated that the MIB-1 labeling index could be helpful as a supplement to the diagnosis of cutaneous BL, particularly when specimens are inadequate. However, differentiating lymphangioendothelioma from angiosarcoma remains challenging. Sevila13 suggested that some previously reported cases of angiosarcoma may actually be benign tumors similar to BL, as they were curable in children and young adults. Therefore, the diagnosis of BL should be used with caution, especially in cases of post-irradiation lesions in adults, as this condition is known to be a precursor to the development of angiosarcoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma.12,43 Audard et al43 even questioned the existence of BL. Hence, careful sampling of such lesions, close correlation of pathological findings with clinical characteristics, and close follow-up care are necessary.

The radiological findings in the present case were typical and quite helpful for the diagnosis and assessment of giant BL before surgery. Lymphoscintigraphy, with subcutaneously injected 99mTc-DX, effectively imaged the lymphatic malformations, enabling a good differential diagnosis from hemangioma or benign hemangioendothelioma and a good assessment of lymphatic uptake, distribution, and retention. The MRI findings were similar to those of hemangiomas, but no signal voids caused by high-flow vessels were observed.40 MRI also helped assess tumor extent, making a valuable contribution to surgery. In the present case, scattered lesions with increased signal density superior to the deep fascia were found on MRI, corresponding to the final pathological result. Ultrasonography can also be useful for localizing and determining the cystic nature of some types of lymphangioma. The imaging examinations allowed for a comprehensive understanding of the nature and extent of the lesion.

Regarding the treatment, the differentiation between lymphangiomatosis and lymphangioendothelioma was not necessary. The main concern was whether the lesion was benign and had the potential for malignant transformation, which would determine if lymph node dissection was required. Due to the patient’s history of clear fluid drainage and the tendency for the mass to infiltrate peripheral subcutis, a type of infiltrating lymphatic malformation with a risk of recurrence was suspected. Despite its penchant for infiltrating peripheral subcutis, the mass showed no signs of invading deeper tissue planes or metastasizing, indicating that the lesion was benign. Given that the lesion had reached the subcutaneous fat and that the patient had undergone two incomplete debridements before admission, thorough surgical excision was the preferred treatment. According to MRI results, the lesion had spread into subcutaneous fat but did not reach the deep fascia, so a complete excision from the skin to the superficial fascia was necessary. The wound boundary was visible to the naked eye, and the scope of the surgery was expanded to ensure a negative margin. Because of the numerous lymphatic fistulas and infections, the temporary coverage by VSD was an important part of the treatment protocols through the application of a controlled and localized negative pressure on porous polyurethane absorbent foams. By controlling infection, calculating the volume lymph fluid, improving lymphorrhea, accelerating tissue granulation, minimizing exposure of deep tissues, and increasing the survival rate of graft transplants for soft-tissue defects, the negative pressure technique played an important role in the protection of a large wound in the lower leg.44 The volume of lymph-like fluid decreased significantly after two surgeries, and the wound no longer exhibited signs of potential sepsis, indicating that skin grafting was possible. Split-thickness skin grafting was chosen after the wound was covered with fresh granulation tissue and showed no evidence of infection. Compared to skin flap, STSG was preferred as it was more effective in preventing recurrent lymphatic malformations since it had less reticular dermis and thus fewer lymphatics. In addition, the patient’s overweight (with a BMI of 28.34) and the wound size made skin flap transplantation risky. Furthermore, the transplantation of the flap from the thigh to the calf might generate morphological issues in the lower leg if microscopic anastomosis was performed. Given the above points, we eventually chose split-thickness skin graft, and we managed to achieve a good functional and cosmetic result. Moreover, medications such as sirolimus, imiquimod, glucocorticoids, and methotrexate have been reported to be effective when surgical excision is not possible due to the size and location of the lesion.9,26,28,45 Positive WT-1 immunostaining indicates a proliferative vascular lesion that requires appropriate therapy such as systemic steroids or interferon, whereas negative results indicate a vascular malformation that does not require unnecessary systemic therapy.35 Interestingly, antibiotic therapy was also effective.16 Since partial or complete spontaneous remission has been documented in some cases,5 therapeutic abstention and pharmaceutic treatment could be reserved for patients when surgery is contraindicated due to the size or location of the lesion.

Conclusion

We have discussed a case of benign lymphangioendothelioma that progressed to a persistent exudative wound after two incomplete excisions. Clinicopathological correlation, imaging examination, and pathological examination are essential for diagnosing BL and excluding lymphangiomatosis, Kaposi’s sarcoma, and angiosarcoma. This case also demonstrates that complete excision and split-thickness skin graft transplant following vacuum-seal drainage is an effective course of treatment for recurrent BL. Additionally, by reviewing the literature on BL, we concluded that BL is more of a pathological diagnosis than a clinical one, and we should allow for more etiological, morphological, and immunohistochemical diversity in the identification of BL.

Data Sharing Statement

All data generated during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

The Ethics Committee of the hospital approved the use of the clinical data of the patient. Consent had been obtained from the patient to use pictures, notes and lab investigations for publication on the condition that the personal information was kept confidential.

Consent for Publication

The consent for publication has been obtained from the patient.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the National Major Disease Multidisciplinary Diagnosis and Treatment Cooperation Project (No.1112320139) and the National clinical key specialty construction project (23003). The funding body played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

1. Jones EW, Feiwel M. Malignant angio-endothelioma. Proc R Soc Med. 1963;56(4):299–300.

2. Wilson Jones E. Malignant vascular tumours. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1976;1(4):287–312. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.1976.tb01435.x

3. Jones EW. MALIGNANT ANGIOENDOTHELIOMA OF THE SKIN. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76(1):21–39. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1964.tb13970.x

4. Gold SC. Angioendothelioma (lymphatic type). Br J Dermatol. 1970;82(1):92–93.

5. Mehregan DR, Mehregan AH, Mehregan DA. Benign lymphangioendothelioma: report of 2 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19(6):502–505. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.1992.tb01604.x

6. Gengler C, Coindre JM, Leroux A, et al. Vascular proliferations of the skin after radiation therapy for breast cancer: clinicopathologic analysis of a series in favor of a benign process: a study from the French Sarcoma Group. Cancer. 2007;109(8):1584–1598. doi:10.1002/cncr.22586

7. Yamada S, Yamada Y, Kobayashi M, et al. Post-mastectomy benign lymphangioendothelioma of the skin following chronic lymphedema for breast carcinoma: a teaching case mimicking low-grade angiosarcoma and masquerading as Stewart-Treves syndrome. Diagn Pathol. 2014;9:197. doi:10.1186/s13000-014-0197-5

8. Guillou L, Fletcher CD. Benign lymphangioendothelioma (acquired progressive lymphangioma): a lesion not to be confused with well-differentiated angiosarcoma and patch stage Kaposi’s sarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of a series. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24(8):1047–1057. doi:10.1097/00000478-200008000-00002

9. Watanabe M, Kishiyama K, Ohkawara A. Acquired progressive lymphangioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8(5):663–667. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(83)70076-9

10. Agha RA, Franchi T, Sohrabi C, Mathew G, Kerwan A. The SCARE 2020 Guideline: updating Consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) Guidelines. Int J Surg. 2020;84:226–230. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034

11. Rosso R, Gianelli U, Carnevali L. Acquired progressive lymphangioma of the skin following radiotherapy for breast carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22(2):164–167. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.1995.tb01401.x

12. McKay MJ, Rady K, McKay TM, McKay JN. A radiation-induced and radiation-sensitive, delayed onset angiosarcoma arising in a precursor lymphangioendothelioma. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5(6):137. doi:10.21037/atm.2017.03.19

13. Sevila A, Botella-Estrada R, Sanmartín O, et al. Benign lymphangioendothelioma of the thigh simulating a low-grade angiosarcoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22(2):151–154. doi:10.1097/00000372-200004000-00011

14. Zhu JW, Lu ZF, Zheng M. Acquired progressive lymphangioma in the inguinal area mimicking giant condyloma acuminatum. Cutis. 2014;93(6):316–319.

15. Wilmer A, Kaatz M, Mentzel T, Wollina U. Lymphangioendothelioma after a tick bite. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(1):126–128. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(98)70416-5

16. Grunwald MH, Amichai B, Avinoach I. Acquired progressive lymphangioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(4):656–657. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70192-0

17. Ando K, Watanabe D, Takama H, Tamada Y, Matsumoto Y. Acquired progressive lymphangioma with atypical clinical presentation. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19(1):82–83. doi:10.1684/ejd.2008.0556

18. Tong PL, Beer TW, Fick D, Kumarasinghe SP. Acquired progressive lymphangioma in a 75-year-old man at the site of surgery 22 years previously. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2011;40(2):106–107. doi:10.47102/annals-acadmedsg.V40N2p106

19. Kato H, Kadoya A. Acquired progressive lymphangioma occurring following femoral arteriography. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1996;21(2):159–162. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.1996.tb00044.x

20. Mizuno K, Okamoto H. Benign lymphangioendothelioma on a vascular birthmark following examination of a cardiac catheter. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54(7):e273–4. doi:10.1111/ijd.12805

21. Herron GS, Rouse RV, Kosek JC, Smoller BR, Egbert BM. Benign lymphangioendothelioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(2 Pt 2):362–368. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70173-3

22. Kim HS, Kim JW, Yu DS. Acquired progressive lymphangioma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21(3):416–417. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01904.x

23. Wang L, Chen L, Yang X, Gao T, Wang G. Benign lymphangioendothelioma: a clinical, histopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of four cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40(11):945–949. doi:10.1111/cup.12216

24. Vittal NK, Kamoji SG, Dastikop SV. Benign Lymphangioendothelioma - A Case Report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(1):Wd01–2. doi:10.7860/jcdr/2016/15664.7155

25. Alkhalili E, Ayoubieh H, O’Brien W, Billings SD. Acquired progressive lymphangioma of the nipple. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014(sep22 1):bcr2014205966–bcr2014205966. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-205966

26. Hunt KM, Herrmann JL, Andea AA, Groysman V, Beckum K. Sirolimus-associated regression of benign lymphangioendothelioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(5):e221–2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.07.054

27. Flores S, Baum C, Tollefson M, Davis D. Pulsed dye laser for the treatment of acquired progressive lymphangioma. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40(2):218–221. doi:10.1111/dsu.12383

28. Salman A, Sarac G, Can Kuru B, Cinel L, Yucelten AD, Ergun T. Acquired progressive lymphangioma: case report with partial response to imiquimod 5% cream. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34(6):e302–e304. doi:10.1111/pde.13283

29. Zhu WY, Penneys NS, Reyes B, Khatib Z, Schachner L. Acquired progressive lymphangioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24(5 Pt 2):813–815. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(91)70120-q

30. Schnebelen AM, Page J, Gardner JM, Shalin SC. Benign lymphangioendothelioma presenting as a giant flank mass. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42(3):217–221. doi:10.1111/cup.12453

31. Larkin SC, Wentworth AB, Lehman JS, Tollefson MM. A case of extensive acquired progressive lymphangioma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35(4):486–489. doi:10.1111/pde.13486

32. Paik AS, Lee PH, O’Grady TC. Acquired progressive lymphangioma in an HIV-positive patient. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34(11):882–885. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00747.x

33. Lin SS, Wang KH, Lin YH, Chang SP. Acquired progressive lymphangioma in the groin area successfully treated with surgery. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34(7):e341–2. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03286.x

34. Teixeira D, Canelhas Á, Costa M, Magalhães C, Ferreira EO, César A. Giant benign lymphangioendothelioma with positive expression of Wilms tumor 1: a case report. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49(1):86–89. doi:10.1111/cup.14125

35. Revelles JM, Díaz JL, Angulo J, Santonja C, Kutzner H, Requena L. Giant benign lymphangioendothelioma. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39(10):950–956. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2012.01971.x

36. Yiannias JA, Winkelmann RK. Benign lymphangioendothelioma manifested clinically as actinic keratosis. Cutis. 2001;67(1):29–30.

37. Tadaki T, Aiba S, Masu S, Tagami H. Acquired progressive lymphangioma as a flat erythematous patch on the abdominal wall of a child. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124(5):699–701. doi:10.1001/archderm.1988.01670050043017

38. Faul JL, Berry GJ, Colby TV, et al. Thoracic lymphangiomas, lymphangiectasis, lymphangiomatosis, and lymphatic dysplasia syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(3):1037–1046. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.161.3.9904056

39. Lindberg MR. Diagnostic Pathology: Soft Tissue Tumors. Springer Science & Business Media; 2019.

40. Weiss SW, Goldblum JR, Folpe AL. Enzinger and Weiss’s soft tissue tumors. Elsevier Health Sci. 2019.

41. Cossu S, Satta R, Cottoni F, Massarelli G. Lymphangioma-like variant of Kaposi’s sarcoma: clinicopathologic study of seven cases with review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19(1):16–22. doi:10.1097/00000372-199702000-00004

42. Elder DE. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014.

43. Audard V, Lok C, Trabattoni M, Wechsler J, Brousse N, Fraitag S. Misleading Kaposi’s sarcoma: usefulness of anti HHV-8 immunostaining. Ann Pathol. 2003;23(4):345–348.

44. Fleischmann W, Strecker W, Bombelli M, Kinzl L. Vacuum sealing as treatment of soft tissue damage in open fractures. Der Unfallchirurg. 1993;96(9):488–492.

45. Tronnier M, Lommel K, Haselbusch D. Acquired progressive lymphangioma in a 13-year-old boy. Hautarzt. 2021;72(7):610–614. doi:10.1007/s00105-020-04728-7

46. Jones EW, Winkelmann RK, Zachary CB, Reda AM. Benign lymphangioendothelioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(2 Pt 1):229–235. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(90)70203-t

47. Renshaw AA, Rosai J. Benign atypical vascular lesions of the lip. A study of 12 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17(6):557–565. doi:10.1097/00000478-199306000-00003

48. Meunier L, Barneon G, Meynadier J. Acquired progressive lymphangioma. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131(5):706–708. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb04988.x

49. Soohoo L, Mercurio MG, Brody R, Zaim MT. An acquired vascular lesion in a child. Acquired progressive lymphangioma. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131(3):341–2, 344–5. doi:10.1001/archderm.1995.01690150107022

50. Hwang LY, Guill CK, Page RN, Hsu S. Acquired progressive lymphangioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(5 Suppl):S250–1. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(03)00448-1

51. Rudra O, Ghosh A, Ghosh SK, Bhunia D, Mandal P. Benign Lymphangioendothelioma: a Report of a Rare Vascular Hamartoma in a Young Indian Child. Indian J Dermatol. 2017;62(5):528–529. doi:10.4103/ijd.IJD_416_16

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.