Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 15

Stressful Life Events and Depression During the Recurrent Outbreak of COVID-19 in China: The Mediating Role of Grit and the Moderating Role of Gratitude

Received 4 February 2022

Accepted for publication 6 May 2022

Published 31 May 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 1359—1370

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S360455

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Haidong Liu,1,* Baojuan Ye,1,* Yong Hu2,*

1School of Psychology & Center of Mental Health Education and Research, Jiangxi Normal University, Nanchang, People’s Republic of China; 2School of Foreign Languages, Jiangxi Normal University, Nanchang, People’s Republic of China

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Correspondence: Yong Hu, School of Foreign Languages, Jiangxi Normal University, Nanchang, People’s Republic of China, Tel +86-185-79113026, Email [email protected]

Purpose: COVID-19 has been exerting tremendous influence on an individual’s physical behavior and mental health. In China, prolonged isolation may lead to depression among college students during the recurrent outbreak of COVID-19. We conducted this study to explore the relationship among stressful life events, grit, gratitude, and depression in college students during the recurrent outbreak of COVID-19.

Methods: We investigated 953 college students from across China, with an average age of 20.38 (SD=1.39) years. Participants completed four scales (Stressful Life Events Scale, Oviedo Grit Scale, Gratitude Questionnaire, and Patients’ Health Questionnaire Depression Scale-9 item).

Results: The present study found that (1) stressful life events were positively correlated with depression in college students; (2) grit mediated the positive relationship between stressful life events and depression; (3) gratitude moderated the relationship between grit and depression, and such that there was a stronger association between grit and depression for college students with high gratitude.

Conclusion: This study was of great significance for studying the relationship between stressful life events and depression in Chinese college students during the recurrent outbreak of COVID-19. Results indicated that grit and gratitude of college students may be the main targets of depression prevention and intervention. The research conclusion has theoretical and reference value for solving and preventing depression in college students during the recurrent outbreak of COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, stressful life events, grit, depression, gratitude, Chinese college students

Introduction

Since the outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020, it has been exerting tremendous influence not only on the physical behavior of individuals, but also on their mental health.1 The COVID-19 outbreak has quickly progressed from a public health emergency of international concern to a pandemic.2 Currently, nearly 500 million people worldwide are infected with COVID-19.3 The way the COVID-19 affects the health of individuals is not only direct, but also other indirect ways, such as loneliness from isolation, financial stress, anxiety about caring for loved ones, depression and suicidality caused by COVID-19.4–8 A survey of seven countries in Asia shows that COVID-19 hits people under the age of 30 most, causing them to significantly increase anxiety and depression.9 A study found a high rate of anxiety or depressive symptoms due to COVID-19 in the population, ranging from 15% to 16%.10 New research has also found that depression is indeed worse during the COVID-19.11

Depression is a key indicator for diagnosing an individual’s mental health, and usually refers to persistent negative emotional experiences in an individual’s life. Individuals with depression usually have sleep disturbances, loss of appetite, and other behaviors. In severe cases, individuals may even self-harm and commit suicide.12 At present, depression has become one of the main diseases that endanger human health.13 In China, the lifetime prevalence of major depression ranges from 2% to 15%.14 While the government’s response has been able to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on mental health,15 depression during COVID-19 has still become one of the diseases that seriously damages the mental health of young people, especially college students.16–22 In China, a study found that depression due to COVID-19 is prevalent among university students,23 and during the COVID-19 pandemic, the estimated prevalence of depression among adolescents is 30.6%.24 Additionally, COVID-19 is strongly associated with depression. Individuals with pre-existing mood disorders, such as depression, are at higher risk of hospitalization and death from COVID-19, and another study shows a high frequency of depressive symptoms associated with post-COVID-19 syndrome.25,26 Also, depression may lead to suicidal ideation, and according to clinical studies, 15% of people with severe depression have a high risk of suicide.27 According to research, temperaments greatly impact psychological distress and suicidality. Among them, the suicide attempt rate of severe depression is as high as 50%, which shows that depression is very harmful to individual psychology.28 Thence, it is of great significance to explore the contributing factors which affect an individual’s depression during the recurrent outbreak of COVID-19.

Stressful Life Events and Depression

Stressful life events are some of the negative life events that people may encounter in daily life and bring pressure to individuals.29 Stressful life events usually have a negative impact on one’s psychological health.30 According to the diathesis-stress interaction theory, depression stems from stress in life,31 and many studies on depression have found that stress in life has a positive predictive effect on depression.32–34 For college students, they are faced with pressure from study, employment, interpersonal relationship, family changes, and so on.35 Study also shows that the pressure of life on college students has increased during the recurrent outbreak of COVID-19.36 On this basis, we believe that stress in life may be a risk factor for depression among college students.

Grit as a Mediator

Previous studies found that stressful life events lead to depression.32–34 Therefore, when we exploring the consequences of stressful life events, it is of great significance to consider the possible mediators that may play a role in the process of stressful life events affecting depression. Studying this mediating role of this path can reveal how the mediator works.37 In the previous researches, there are many studies on depressive symptoms of college students, but less attention is paid to the psychopathological status of adolescents from the perspective of positive psychology. Positive psychology pays more attention to the positive characteristics of individuals and the influencing factors of individual development protection. As an important psychological trait, grit has been one of the research hotspots in psychology in recent years.38–40 As a non-cognitive ability, grit is a constant passion and perseverance for long-term goals.41 Studies have found that grit plays an indispensable role in mental health. Grit helps individuals stay mentally healthy in adapting to social change, and grit is positively correlated with happiness and life satisfaction.42,43 Studies have shown that stressful life events were negatively related to an individual’s grit,44 and experiencing more stressful life events reduces an individual’s level of grit, which in turn reduces his ability to cope with other difficulties in life. From the perspective of resource theory,45 college students’ grit is an important positive psychological resource for individuals to cope with life pressure. For an individual, the higher his level of grit, the easier it is for him to see difficulties and stress in life as an inevitable part of the struggle, and this attitude makes individuals with a higher level of grit qualities be less likely to be depressed.46 Therefore, we propose that grit could play a mediating role in the relationship between stressful life events and depression during the recurrent outbreak of COVID-19.

The Moderating Role of Gratitude

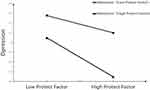

In addition to grit, gratitude has been one of the hottest topics in positive psychology in recent years.47,48 Gratitude refers to an emotional trait in which an individual responds to others’ help with gratitude to obtain positive experiences or results, which can make a positive effect on an individual’s mental development.49 As a positive emotional trait and a positive personality trait, gratitude is closely and positively correlated with mental health, happiness,50 however, other researchers have found that gratitude is closely related to an individual’s negative emotions. According to the extended construction theory of gratitude, individuals with high gratitude pay more attention to the construction of interpersonal relationships and are more adept at using their interpersonal resources to solve problems, thus reducing negative emotions that affect them, such as depression.51,52 Lin53,54 found that gratitude is an important protective factor for adolescent psychological health and can significantly negatively predict the depression of college students. Many scholars have studied and discovered the relationship between gratitude and grit. Kleiman55 found that grit and gratitude interacted to eventually reduce an individual’s suicidal ideation. Therefore, in addition to grit, gratitude can also reduce the risk of depression, both of which are protective factors against depression. In the theory about the protective-protective model,56 the existence of one protective factor can enhance the effect of another protective factor (see Figure 1). According to the model, the effect of protective factors (grit) on depression in college students will be greater for individuals with high protective factors (gratitude). Therefore, we hypothesized that gratitude might enhance the effect of grit on depression, that is, the effect of grit on depression was reinforced for individuals with high gratitude, but weakened for individuals with low gratitude.

|

Figure 1 The Protective-Protective model. |

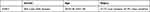

In conclusion, the study constructed a moderated mediation model (see Figure 2) to test the mediating effect of grit and the moderating effect of gratitude. Based on existing research and theories, this study puts forward three specific hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Stressful life events significantly positively relate to depression in college students. Hypothesis 2: Grit mediates the relationship between stressful life events and depression. Hypothesis 3: Gratitude moderates the association between grit and depression.

|

Figure 2 The proposed theoretical model. |

Materials and Methods

Participants

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the first author’s university. In this study, participants over the age of 18 provided informed consent, and participants under the age of 18 obtained the consent of their legal guardians. 977 Chinese college students were recruited in China. The criteria for unqualified participants were less than 100 seconds to complete questionnaires with a total of 41 questions and regularity of answers, such as the same score in each item or a regular pattern of scores (1, 2, 3, 4, 5 etc.). After excluding unqualified individuals (eg, completing questionnaire less than 100 seconds and answering regularly), we finally collected 953 valid questionnaires with an effective response rate of 97.54% from 977 primary questionnaires. Among them, there were 381 males (40%) and 572 females (60%), aged between 17 and 24 (M=20.38, SD=1.39). There were 306 (32.1%) rural residents and 647 (67.9%) urban residents. The participants’ baseline characteristics were shown in Table 1. Since gender, age, and region may have a certain impact on mental health, we also controlled for these three variables in the subsequent analysis.

|

Table 1 Participants’ Baseline Characteristics |

Instruments

Stressful Life Events Scale

The stressful life events were assessed with the Stressful Life Events Scale,57 which consists of 16 items (eg, “falling behind in study”). Each item was rated on a 6-point scale (0=did not occur to 5=occurred and extremely stressful). The average score for each of the 16 items was calculated. The higher the score, the greater of stressful life events they experienced. Compared with the traditional Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, the composite reliability is more accurate to estimate the test reliability of the scale.58,59 The composite reliability of the scale in this study was 0.95.

Depression Scale

Depression in this study was assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire Depression Self-Rating Scale. Bian60 revised the scale in Chinese. There are nine items (eg, “Feeling down depressed or hopeless”), and each item was rated on a 4-point scale (0= not at all to 3= almost every day), with higher total scores indicating higher levels of depression. The composite reliability of the scale in this study was 0.94.

Grit Scale

College students’ grit was assessed with new version of the grit scale-Oviedo Grit Scale developed by Postigo,61 which was used to measure grit. The scale is one-dimensional, with 10 items (eg, “When I set myself an objective, I continue until I achieve it”). Participants rated each item on a 5-point scale (1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree). Higher scores indicated higher levels of grit of the individual. In this study, these 10 items were forward and back-translated by Chinese professors who were fluent in both Chinese and English. We made some minor changes to ensure that these items can be adapted to typical Chinese culture. The scale had good validity in this study and was in line with various psychometrics standards. The composite reliability for this scale was 0.891. Validity information of the Oviedo Grit Scale from the current sample (N=953) was CFI = 0.974, TLI = 0.966, Chi-Square = 96.546, df = 35, RMSEA = 0.051, SRMR = 0.024.

Gratitude Scale

The college students’ gratitude was assessed with a 6-item questionnaire, which was adapted from the gratitude questionnaire,49 and the Chinese vision was revised by Li.62 There were 6 items in the questionnaire (eg, “If had to list everything that I felt grateful for, it would be a very long list”). College students rated each item on a 7-point scale (1=strongly disagree to 7=strongly agree). The average score of the six items was calculated. The higher the average score obtained by the individual, the higher the level of gratitude. The composite reliability of the scale in this study was 0.93.

Procedure

Specifically, this research publishes recruitment information on the internet, and interested participants can participate in the research. Participants completed a survey anonymously to collect information on gender, age group, stressful life events, grit, gratitude and depression. The survey was hosted on Wenjuan Web63 (Shanghai Zhongyan International Science and Technology, Shanghai, China) from December 23–31, 2021. In this study, participants provided informed consent. In this study, all responses were anonymous. There was no compensation for participating in this study, and the participants participated entirely voluntarily. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the first author’s university.

Statistical Analysis

First of all, SPSS26.0 was used to calculate the descriptive statistics for the study variables, and then their correlation among the study variables was calculated. Next, the Bootstrap method (with 5000 resampling) was used to test the mediation effect and moderating effect. We tested the mediating effect of grit by using the PROCESS (Model 4) macro of SPSS26.0 software.64 Thirdly, we investigated the moderating effect of gratitude on the indirect relationship between grit and depression by using the PROCESS (Model 14) macro of SPSS26.0 software.64 The bootstrap confidence intervals (based on 5000 random samples) was used to determine whether the effects in Model 4 and Model 14 were significant.64

Result

Preliminary Analyses

Correlations and descriptive statistics of all variables were shown in Table 2. The skewness and kurtosis values of each variable were within the acceptable range, and the data can be considered to generally met a normal distribution (Skewness < |3.0| and Kurtosis < |10.0|).65 Stressful life events were significantly positively associated with depression (r=0.615, p<0.001), and significantly negatively associated with grit (r=−0.081, p<0.05) and gratitude (r=−0.306, p<0.001). Grit was significant positively associated with gratitude (r=0.271, p<0.001) and significant negatively associated with depression (r=−0.204, p<0.001). Gratitude was significantly associated with depression (r=−0.409, p<0.001).

|

Table 2 Correlations Among Variables |

|

Table 3 Testing the Mediation Effect of Stressful Life Events on Depression |

Analysis for Mediation Effect

We assumed that grit played a mediating role in the relationship between stressful life events and depression in hypothesis 2. So, we tested the mediation effect with Model 4 of the PROCESS.64 As Table 3 Model 1 (Depression) showed, stressful life events were positively associated with depression in college students (β=0.614, SE=0.026, p<0.001, 95% CI [0.565, 0.666]). This meant that stressful life events were significantly positively associated with depression in college students, therefore hypothesis 1 was supported. According to Model 2 (Grit) and Model 3 (Depression), stressful life events were significant positively related to depression (β=0.601, SE=0.025, p<0.001, 95% CI [0.553, 0.652]) and significant negatively related to grit (β=−0.086, SE=0.032, p<0.01, 95% CI [−0.150,-0.023]). The negative association between grit and depression remained significantly (β=−0.157, SE=0.025, p<0.001, 95% CI [−0.204,-0.105]). Thus, hypothesis 2 was supported.

Moderated Mediation Effect Analysis

The PROCESS of the SPSS macro program was used to test the moderated mediation model and evaluate the moderating effect of gratitude on grit and depression. The results were shown in Table 3, Model 4 (Depression). Stressful life events were significant positively associated with depression (β=0.537, SE=0.026, p<0.001, 95% CI [0.490, 0.590]). The association between grit and depression remained significantly (β=−0.098, SE=0.025, p<0.001, 95% CI [−0.148,-0.048]). Gratitude was negatively related to depression (β=−0.219, SE=0.027, p<0.001, 95% CI [−0.270,-0.167]), and the product (interaction term) of gratitude and grit had a significant predictive effect on depression (β=−0.052, SE=0.022, p<0.05, 95% CI [−0.095,-0.009]), suggesting that gratitude could moderate the relationship between grit and depression. Specifically, gratitude could moderate the second half of the indirect pathway. Hypothesis 3 was supported.

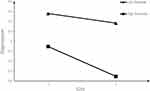

For description purposes, we plotted examined grit against depression, separately for low and high levels of gratitude. The interaction effect was visually plotted in Figure 3. Simple slope tests showed that for college students with high gratitude, grit was significantly associated with perceived depression, βsimple=−0.150, t=−4.604, p<0.001, 95% CI= [−0.214,-0.086]. As for college students with low gratitude, grit had no significant effect on depression, βsimple =−0.046, t=−1.316, p>0.05, 95% CI [−0.113,0.022].

|

Figure 3 Interaction between gratitude and grit on depression. |

Discussion

Through a survey of 953 Chinese college students, this study found that stressful life events were significant positively associated with depression in college students during the recurrent outbreak of COVID-19. According to the diathesis-stress interaction theory,31 some stressful events in life may lead to individual depression. The results of this study support the diathesis-stress interaction theory and confirm that during the recurrent outbreak of COVID-19, college students who experience more stressful life events were more likely to suffer from depression. The results also showed that grit played a partial mediating role in the relationship between stressful life events and college students’ depression. Moreover, the relationship between grit and depression was further moderated by gratitude.

The Mediating Role of Grit

To our knowledge, this study was the first to identify a mediating role for grit in the relationship between stressful life events and depression during the recurrent outbreak of COVID-19. The results of this study showed that grit was a significant and partial mediator between stressful life events and depression. Grit, as an important concept of individual positive traits in positive psychology, plays an important role in individual physical and mental development. Grit is a non-cognitive structure of psychological traits, which is considered a positive factor for individual physical and mental development in the current research on positive psychology. Therefore, individuals with a higher level of grit can also show more and more positive psychological characteristics and behaviors. Similarly, individuals with lower levels of grit exhibit more negative behaviors. Previous studies have also found that grit negatively predicts individual depression.46 In the present study, the impact of stressful life events on individuals reduced their grit traits during the recurrent outbreak of COVID-19. As reflected in previous studies, grit was negatively correlated with depression,46 and decreasing in grit may likely be related to the increased risk of depression among college students during the recurrent outbreak of COVID-19. Hence, in addition to paying attention to stressful life events, mental health interventions for college students are equally necessary to target grit to mitigate college students’ depression.

Grit partially mediated the relationship between stressful life events and depression. Therefore, during the recurrent outbreak of COVID-19, in addition to grit, there may be other factors that link stressful life events with depression.66 Future research can start in this direction, for example, behavioral outcomes due to the recurrent outbreak of COVID-19 and the stress associated with them (ie, epidemic risk percept) could influence individual mental health, and ultimately depression.66 Therefore, it is necessary to further investigate other relevant mechanisms of the direct association between stressful life events and depression during the recurrent outbreak of COVID-19.

The Moderating Role of Gratitude

Results of this study showed that gratitude, as a positive factor of individual physical and mental development, significantly moderated the relationship between grit and depression during the recurrent outbreak of COVID-19. Based on the perspective of positive psychology, this study explored whether the mediating effect of grit on stressful life events and depression varies with the level of gratitude among college students. The mediating model of the effect of stressful life events on depression through grit was further studied and discussed by adding the constraint of “when” the influence was stronger. The results showed that gratitude has a significant negative impact on depression among college students during the recurrent outbreak of COVID-19. This is consistent with previous research.51–53 Grit had no significant inhibitory effect on depression for college students with low gratitude. But for college students with high gratitude, grit has a significant inhibitory effect on depression, that is, the higher the quality of grit, the lower the level of depression. According to the gratitude coping hypothesis, individuals with high gratitude will adopt a positive way to cope with pressure and difficulties, whereas individuals with low gratitude will adopt a more negative way to cope with hardships in life, resulting in negative behaviors such as avoidance, which will adversely affect individual physical and mental health.67 Fredrickson51,52 believes that highly grateful individuals are good at dealing with interpersonal relationships and can obtain help and support from interpersonal resources when facing difficulties, thus reducing irritability and depression. According to the protective-protective model,56 gratitude as a protective factor strengthens the effect of grit on depression. This study also confirmed the above conclusions once again, and also provided some enlightenment for the prevention of college students’ depression in the future. It is of great significance to pay attention to the education of gratitude for college students to improve their mental health, especially during the recurrent outbreak of COVID-19.

Limitations

Although this study examined the internal mechanisms of stressful life events and depression, there were some limitations. First of all, this study used the cross-sectional design, which makes it impossible to infer the causal relationship between variables. So experimental and longitudinal designs could be utilized in future research. Secondly, the self-reported questionnaire survey used in this study may be affected by social desirability, especially for those variables with very high social desirability, such as depression and grit. In the future, measures with less social desirability effect could be considered. Thirdly, this study did not fully assess factors that could influence mental health (ie, financial stress, anxiety, caring for loved ones etc.). Future studies should control such factors that could influence mental health. Lastly, this study did not explore other factors that may affect mental health and show differences between Chinese and other cultures including: (1) The use of masks which have a protective effect on the mental health of the Chinese;68 (2) Vaccination willingness that Chinese people with depression and anxiety have higher vaccination rates;69 (3) Influence of religion that religion and religious activities in China are less than in other countries;70 (4) discrimination that Chinese experience more discrimination than another country;71 (5) The role of health information for Chinese that health information are good for Chinese mental health;72 (6) Acute-traumatic stress symptoms in China that Chinese reported higher acute-traumatic stress symptoms than another country.73

Even though there are some limitations, the contributions of the research are both theoretical and practical. This study not only enriched the theoretical model of the effect of stressful life events on college students’ depression but also provided reference value for the prevention and treatment of college students’ depression. Firstly, college students tend to experience more stress during the recurrent outbreak of COVID-19, and stressful life events not only directly affect college students’ depression, but also increase their risk of depression by reducing individuals’ grit. Therefore, attention should be paid to the cultivation of college students’ grit. Duckworth74 believes that grit is of great significance for individual development, especially for the growth and development of college students. This study can inspire educators to attach importance to cultivating individuals’ grit, promoting their mental health development, and reducing the risk of depression. According to the research results, gratitude can moderate the influence of grit on depression among college students, therefore, attention should be paid to the cultivation of gratitude in college students, which can effectively prevent depression among college students. Specifically, for depression treatment during COVID-19, we can take online psychotherapy. The most evidence-based treatment is cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), and CBT is to guide patients to monitor, identify, and correct distorted cognitions related to problems, assisting patients to correctly recognize gains and losses, helping maladaptive behaviors, as well as forming positive interactions in emotion, behavior, and cognition.75 It is characterized by high safety, and although the onset is slower, it can reduce depressive symptoms. During COVID-19, Internet CBT is a great option for treating depression. First, Internet CBT can prevent the spread of infection during the pandemic; second, Internet CBT is cost-effective and could effectively treat psychiatric symptoms during COVID-19.76,77 Internet CBT can help people in the epidemic rebuild the cognitive structure of grit and gratitude, re-evaluate themselves, let them believe that they can achieve grit and gratitude, and establish a correct psychological coping style. Finally, stressful life events not only increase the risk of depression in college students but also weaken the level of grit of college students. Therefore, we should pay attention to improving the living environment of college students, and appropriately relieving pressure on college students, especially during this particular time of the recurrent outbreak of COVID-19.

Conclusion

To sum up, the study was of great importance in exploring how stressful life events were related to Chinese college students’ depression during the recurrent outbreak of COVID-19, even if further replication and extension were required. This study showed that grit served as a potential mechanism by which stressful life events were associated with depression. The focus on grit brought additional nuances in linking stressful life events to college students’ depression. In addition, gratitude moderated the relationship between grit and depression, and the relationship between grit and depression became stronger for college students with high gratitude during the recurrent outbreak of COVID-19. Online psychotherapy (eg, Internet CBT) may be helpful for college students with psychological problems during the recurrent outbreak of COVID-19. Therefore, school workers should not only focus on reducing stressful life events in the lives of college students but also focus on cultivating the grit and gratitude of college students to prevent depression.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets used in this study are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of school of Psychology, Jiangxi Normal University. All participants reviewed the consent form before they participated in the study.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to all the participants and volunteers who provided support for this study. Haidong Liu, Baojuan Ye, and Hu Yong are co-first authors for this study.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interest in this work.

References

1. Wang C, Chudzicka-Czupała A, Tee ML, et al. A chain mediation model on COVID-19 symptoms and mental health outcomes in Americans, Asians and Europeans. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):6481. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-85943-7

2. Garcia M, Lipskiy N, Tyson J, Watkins R, Esser ES, Kinley T. Centers for disease control and prevention 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) information management: addressing national health-care and public health needs for standardized data definitions and codified vocabulary for data exchange. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27(9):1476–1487. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocaa141

3. WHO (COVID-19) Homepage. WHO health emergency dashboard [homepage on the Internet]; 2022. Available from: https://covid19.who.int.

4. Mucci F, Mucci N, Diolaiuti F. Lockdown and isolation: psychological aspects of covid-19 pandemic in the general population. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2020;17(2):63–64. doi:10.36131/CN20200205

5. Bhanot D, Singh T, Verma SK, Sharad S. Stigma and discrimination during COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. 2021;8:577018. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2020.577018

6. Wilson JM, Lee J, Fitzgerald HN, Oosterhoff B, Sevi B, Shook NJ. Job insecurity and financial concern during the COVID-19 pandemic are associated with worse mental health. J Occup Environ Med. 2020;62(9):686–691. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000001962

7. Prime H, Wade M, Browne DT. Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am Psychol. 2020;75(5):631–643. doi:10.1037/amp0000660

8. Xiong J, Lipsitz O, Nasri F, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:55–64. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001

9. Wang C, Tee M, Roy AE, et al. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on physical and mental health of Asians: a study of seven middle-income countries in Asia. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0246824. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0246824

10. Cénat JM, Blais-Rochette C, Kokou-Kpolou CK, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021;295:113599. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113599

11. Oh H, Marinovich C, Rajkumar R, et al. COVID-19 dimensions are related to depression and anxiety among US college students: findings from the Healthy Minds Survey 2020. J Affect Disord. 2021;292:270–275. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.121

12. Felger JC, Haroon E, Miller AH. Risk and resilience: animal models shed light on the pivotal role of inflammation in individual differences in stress-induced depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78(1):7–9. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.04.017

13. Paykel ES, Brugha T, Fryers T. Size and burden of depressive disorders in Europe. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;15(4):411–423. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.04.008

14. Lee S, Tsang A, Huang YQ, et al. The epidemiology of depression in metropolitan China. Psychol Med. 2009;39(5):735–747. doi:10.1017/S0033291708004091

15. Lee Y, Lui LMW, Chen-Li D, et al. Government response moderates the mental health impact of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of depression outcomes across countries. J Affect Disord. 2021;290:364–377. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.04.050

16. Talapko J, Perić I, Vulić P, et al. Mental health and physical activity in health-related university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare. 2021;9(7):801. doi:10.3390/healthcare9070801

17. Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(5):1729. doi:10.3390/ijerph17051729

18. Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:40–48. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028

19. Tan W, Hao F, McIntyre RS, et al. Is returning to work during the COVID-19 pandemic stressful? A study on immediate mental health status and psychoneuroimmunity prevention measures of Chinese workforce. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:84–92. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.055

20. Hao F, Tan W, Jiang L, et al. Do psychiatric patients experience more psychiatric symptoms during COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown? A case-control study with service and research implications for immunopsychiatry. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:100–106. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.069

21. Hao F, Tam W, Hu X, et al. A quantitative and qualitative study on the neuropsychiatric sequelae of acutely ill COVID-19 inpatients in isolation facilities. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10(1):355. doi:10.1038/s41398-020-01039-2

22. Ren Z, Xin Y, Wang Z, Liu D, Ho RCM, Ho CSH. What factors are most closely associated with mood disorders in adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic? A cross-sectional study based on 1771 adolescents in Shandong Province, China. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:728278. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.728278

23. Yu Y, She R, Luo S, et al. Factors influencing depression and mental distress related to COVID-19 among university students in China: online cross-sectional mediation study. JMIR Ment Health. 2021;8(2):e22705. doi:10.2196/22705

24. Zhu J, Racine N, Xie EB, et al. Post-secondary student mental health during COVID-19: a meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:777251. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.777251

25. Ceban F, Nogo D, Carvalho IP, et al. Association between mood disorders and risk of COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(10):1079–1091. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.1818

26. Renaud-Charest O, Lui LMW, Eskander S, et al. Onset and frequency of depression in post-COVID-19 syndrome: a systematic review. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;144:129–137. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.09.054

27. Orsolini L, Latini R, Pompili M, et al. Understanding the complex of suicide in depression: from research to clinics. Psychiatry Investig. 2020;17(3):207–221. doi:10.30773/pi.2019.0171

28. Baldessarini RJ, Innamorati M, Erbuto D, et al. Differential associations of affective temperaments and diagnosis of major affective disorders with suicidal behavior. J Affect Disord. 2017;210:19–21. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.003

29. March-Llanes J, Marqués-Feixa L, Mezquita L, Fañanás L, Moya-Higueras J. Stressful life events during adolescence and risk for externalizing and internalizing psychopathology: a meta-analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;26(12):1409–1422. doi:10.1007/s00787-017-0996-9

30. Rawat S, Rajkumari S, Joshi PC, Khan MA, Saraswathy KN. Risk factors for suicide attempt: a population-based -genetic study from Telangana, India. Curr Psychol. 2019;40(10):5124–5133. doi:10.1007/s12144-019-00446-z

31. Monroe SM, Simons AD. Diathesis-stress theories in the context of life stress research: implications for the depressive disorders. Psychol Bull. 1991;110(3):406–425. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.110.3.406

32. Dentale F, Vecchione M, Alessandri G, Barbaranelli C. Investigating the protective role of global self-esteem on the relationship between stressful life events and depression: a longitudinal moderated regression model. Curr Psychol. 2018;39(6):2096–2107. doi:10.1007/s12144-018-9889-4

33. Hammen C. Stress and depression. Annu Rev Clin Psycho. 2005;1(1):293–319. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803

34. Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Prescott CA. Causal relationship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(6):837–841. doi:10.1176/ajp.156.6.837

35. Arbona C, Jimenez C. Minority stress, ethnic identity, and depression among Latino/a college students. J Couns Psychol. 2014;61(1):162–168. doi:10.1037/a0034914

36. Coiro MJ, Watson KH, Ciriegio A, et al. Coping with COVID-19 stress: associations with depression and anxiety in a diverse sample of U.S. adults. Curr Psychol. 2021. doi:10.1007/s12144-021-02444-6

37. Mackinnon DP, Fairchild AJ. Current directions in mediation analysis. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2009;18(1):16. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01598.x

38. Abu Hasan HE, Munawar K, Abdul Khaiyom JH. Psychometric properties of developed and transadapted grit measures across cultures: a systematic review. Curr Psychol. 2020. doi:10.1007/s12144-020-01137-w

39. Kuruveettissery S, Gupta S, Rajan SK. Development and psychometric validation of the three-dimensional grit scale. Curr Psychol. 2021. doi:10.1007/s12144-021-01862-w

40. Rusadi RM, Sugara GS, Isti’adah FN. Effect of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on academic grit among university student. Curr Psychol. 2021. doi:10.1007/s12144-021-01795-4

41. Duckworth AL, Peterson C, Matthews MD, Kelly DR. Grit: perseverance and passion for long-term goals. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;92(6):1087–1101. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1087

42. Beasley M, Thompson T, Davidson J. Resilience in response to life stress: the effects of coping style and cognitive hardiness. Personal Individ Differ. 2003;34(1):77–95. doi:10.1016/s0191-8869(02)00027-2

43. Mia MV, Daiva D. Grit and different aspects of well-being: direct and indirect relationships via sense of coherence and authenticity. J Happiness Stud. 2016;17(5):2119–2147. doi:10.1007/s10902-015-9688-7

44. O’Neal CR, Espino MM, Goldthrite A, et al. Grit under duress. Hispanic J Behav Sci. 2016;38(4):446–466. doi:10.1177/0739986316660775

45. Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. J Occup Organ Psych. 2011;84(1):116–122. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8325.2010.02016.x

46. Datu JAD, Yuen M, Chen G. Grit and determination: a review of literature with implications for theory and research. J Psychol Counc Sch. 2017;27(2):168–176. doi:10.1017/jgc.2016.2

47. Gulliford L, Morgan B, Hemming E, Abbott J. Gratitude, self-monitoring and social intelligence: a prosocial relationship? Curr Psychol. 2019;38(4):1021–1032. doi:10.1007/s12144-019-00330-w

48. Lasota A, Tomaszek K, Bosacki S. How to become more grateful? The mediating role of resilience between empathy and gratitude. Curr Psychol. 2020. doi:10.1007/s12144-020-01178-1

49. Mccullough ME, Emmons RA, Tsang JA. The grateful disposition: a conceptual and empirical topography. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;82(1):112–127. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.82.1.112

50. Azad Marzabadi E, Mills PJ, Valikhani A. Positive personality: relationships among mindful and grateful personality traits with quality of life and health outcomes. Curr Psychol. 2018;40(3):1448–1465. doi:10.1007/s12144-018-0080-8

51. Fredrickson BL. Gratitude, like other positive emotions, broaden and builds. In: Emmons RA, McCullough ME, editors. The Psychology of Gratitude. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004.

52. Fredrickson BL. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am Psychol. 2001;56(3):218–226. doi:10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.218

53. Lin CC. The relationships among gratitude, self-esteem, depression, and suicidal ideation among undergraduate students. Scand J Psychol. 2015;56(6):700–707. doi:10.1111/sjop.12252

54. Lin CC. The effects of gratitude on suicidal ideation among late adolescence: a mediational chain. Curr Psychol. 2019;40(5):2242–2250. doi:10.1007/s12144-019-0159-x

55. Kleiman EM, Adams LM, Kashdan TB, Riskind JH. Gratitude and grit indirectly reduce risk of suicidal ideations by enhancing meaning in life: evidence for a mediated moderation model. J Res Pers. 2013;47(5):539–546. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2013.04.007

56. Fergus S, Zimmerman MA. Adolescent resilience: a framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26(1):399–419. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357

57. Liu X, Liu L, Yang J, Zhao G. Reliability and validity of the adolescent self-rating life events checklist. Chinese J Clin Psychol. 1997;5:34–36.

58. Torsheim T, Samdal O, Rasmussen M, Freeman J, Griebler R, Dür W. Cross-national measurement invariance of the teacher and classmate support scale. Soc Indic Res. 2012;105(1):145–160. doi:10.1007/s11205-010-9770-9

59. Yang Y, Green SB. A note on structural equation modeling estimates of reliability. Struct Equ Modeling. 2010;17(1):66–81. doi:10.1080/10705510903438963

60. Bian CD, He XY, Qian J, et al. The reliability and validity of a modified patient health questionnaire for screening depressive syndrome in general hospital outpatients. J Tongji U. 2013;30(5):136–140.

61. Postigo Á, Cuesta M, García-Cueto E, Menéndez-Aller Á, González-Nuevo C, Muñiz J. Grit assessment: is one dimension enough? J Pers Assess. 2020;103:786–796. doi:10.1080/00223891.2020.1848853

62. Li D, Zhang W, Li X, Li N, Ye B. Gratitude and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among Chinese adolescents: direct, mediated, and moderated effects. J Adolesc. 2012;35(1):55–66. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.06.005

63. Wenjuan Web [homepage on the Internet]. Shanghai: Shanghai Zhongyan International Science and Technology; 2022. Available from: https://www.wenjuan.com.

64. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2013.

65. Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling.

66. Nie XD, Wang Q, Wang MN, et al. Anxiety and depression and its correlates in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2021;25(2):109–114. doi:10.1080/13651501.2020.1791345

67. Wood AM, Joseph S, Linley PA. Coping style as a psychological resource of grateful people. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2007;26(9):1076–1093. doi:10.1521/jscp.2007.26.9.1076

68. Wang C, Chudzicka-Czupała A, Grabowski D, et al. The association between physical and mental health and face mask use during the COVID-19 pandemic: a comparison of two countries with different views and practices. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:569981. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.569981

69. Hao F, Wang B, Tan W, et al. Attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination and willingness to pay: comparison of people with and without mental disorders in China. BJPsych Open. 2021;7(5):e146. doi:10.1192/bjo.2021.979

70. Wang C, Fardin MA, Shirazi M, et al. Mental health of the general population during the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic: a tale of two developing countries. Psychiatry Int. 2021;2(1):71–84. doi:10.3390/psychiatryint2010006

71. Wang C, López-Núñez MI, Pan R, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical and mental health in China and Spain: cross-sectional study. JMIR Form Res. 2021;5(5):e27818. doi:10.2196/27818

72. Tee M, Wang C, Tee C, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical and mental health in lower and upper middle-income Asian countries: a comparison between the Philippines and China. Front Psychiatry. 2021;11:568929. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.568929

73. Wang C, Tripp C, Sears SF, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical and mental health in the two largest economies in the world: a comparison between the United States and China. J Behav Med. 2021;44(6):741–759. doi:10.1007/s10865-021-00237-7

74. Duckworth A, Gross JJ. Self-control and grit: related but separable determinants of success. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2014;23(5):319–325. doi:10.1177/0963721414541462

75. Ho CS, Chee CY, Ho RC. Mental health strategies to combat the psychological impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) beyond paranoia and panic. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2020;49(3):155–160. doi:10.47102/annals-acadmedsg.202043

76. Zhang MW, Ho RC. Moodle: the cost effective solution for internet cognitive behavioral therapy (I-CBT) interventions. Technol Health Care. 2017;25(1):163–165. doi:10.3233/THC-161261

77. Soh HL, Ho RC, Ho CS, Tam WW. Efficacy of digital cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sleep Med. 2020;75:315–325. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2020.08.020

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.