Back to Journals » OncoTargets and Therapy » Volume 12

Should S-1 be better than capecitabine for patients with advanced gastric cancer in Asia? A systematic review and meta-analysis

Authors Ye Z , Chen J , Rao Y , Yang W

Received 17 September 2018

Accepted for publication 1 December 2018

Published 27 December 2018 Volume 2019:12 Pages 269—277

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/OTT.S187815

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Prof. Dr. Takuya Aoki

Ziqi Ye,1,* Jie Chen,2,* Yuefeng Rao,1 Wenchao Yang3

1Department of Pharmacy, The First Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China; 2Department of Pharmacy, The Second Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China; 3Department of Pharmacy, Traditional Chinese Medical Hospital of Zhuji, Zhuji, China

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Background: S-1 or capecitabine (Cap) containing treatment is an increasingly used strategy in patients with advanced gastric cancer in Asia. It is unclear whether there is sufficient evidence to support which regimen is better.

Methods: A systematic review of retrospective studies and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing S-1 with Cap containing treatment in advanced gastric cancer patients was performed. Embase, PubMed, Clinical Trials.gov, Cochrane Library, and reference lists were searched from inception until August 2018 for relevant studies. Outcomes of interest included 1-year overall survival (OS), 1-year progression-free survival (PFS), objective response rate (ORR), and adverse events. Meta-analyses of the random events were performed. We also performed sensitivity analysis to examine whether the results of the meta-analyses were robust.

Results: A total of 770 subjects from six RCTs and two retrospective studies in Asia were analyzed. Compared with S-1, Cap containing treatment had better ORR (overall risk ratio =0.85, 95% CI: 0.72, 0.99, I2=0%, P=0.043) and higher incidence of all-grade hand-foot syndrome (HFS) (overall risk ratio =0.29, 95% CI: 0.20, 0.40, I2=0%, P<0.001) and neutropenia (overall risk ratio =0.85, 95% CI: 0.73, 0.99, I2=0%, P=0.039). But there was no statistical difference in 1-year PFS, 1-year OS, incidence of other all-grade or grade 3–4 adverse events between S-1 and Cap containing arms (P>0.05). We found no publication bias in this review.

Conclusion: This systematic review showed that for Asian patients, Cap shows superiority in ORR but not 1-year OS or PFS, and it will increase the risk of all-grade HFS and neutropenia. Until now, S-1 containing treatment might be a better choice for advanced gastric cancer patients. But more high-quality RCTs are needed to confirm these results.

Keywords: 1-year OS, 1-year PFS, adverse events, ORR, HFS, neutropenia

Introduction

Globally, gastric cancer is one of the most common cancers.1 In Asia, gastric cancer is a major health concern. The highest 5-year survival rates between 2010 and 2014 were seen in Southeast Asia: 68.9% in South Korea and 60.3% in Japan. But in China, the 5-year survival rate was only 35.9%.1 Most gastric cancer patients are symptomatic and already have advanced incurable disease at the time of presentation. The first-line regimens for advanced gastric cancer are combination chemotherapy consisting of a fluoropyrimidine (oral fluoropyrimidine or 5-fluorouracil [5-FU]) plus a platinum agent. A meta-analysis and a number of controlled trials provided evidence for the survival benefit of palliative systemic chemotherapy in patients with advanced gastric cancer.2–6

Until now, fluoropyrimidines are still the most common agents for gastric cancer in various settings. 5-FU, administered as a continuous infusion, can prolong exposure and moderately improve the efficacy. However, infusion is relatively unsafe and inconvenient, and it can cause more hematological toxicity, catheter-related events, and hand-foot syndrome (HFS).7

For this reason, oral fluoropyrimidine (S-1 and capecitabine [Cap]) has been studied as a substitute for continuous 5-FU infusion. S-1 is an oral formulation of the following components in a 1:0.4:1 ratio:8 tegafur, the prodrug for cytotoxic fluoropyrimidines; 5-chloro-2,4-dihydroxypyridine, an inhibitor of dihydroxypyridine dehydrogenase, which prevents its degradation in the gastrointestinal tract, thus prolonging its half-life;9 and oteracil, a specific inhibitor of one of the enzymes, orotate phosphoribosyl transferase, which phosphorylates fluoropyrimidines in the intestine. Clinical evidence showed that S-1 had an equal efficacy but better toxicity profile compared with 5-FU infusion.10 Cap is an oral fluoropyrimidine which is primarily metabolized in the liver and converted to 5-FU in tumor tissues. A meta-analysis showed a superior overall survival (OS) in patients treated with Cap than with 5-FU.11 For their oral formulations, favorable toxicity profiles, and promising efficacy, S-1 and Cap may be attractive for elderly cancer patients.

In Asia, both S-1 and Cap containing regimens are recommended for advanced gastric cancer patients, but there is no clear consensus as to which regimen is better. Recently, a meta-analysis indicated that S-1-based regimens had a similar efficacy compared with Cap-based regimens, but was associated with a significant lower rate of grade 1–2 HFS and grade 3–4 neutropenia.12 However, only three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included. As there is now more data available, a systematic review and meta-analysis was performed in order to assess whether or not S-1 should be considered better than Cap in Asian patients with advanced gastric cancer.

Methods

Search strategy

To examine the differences between S-1 and Cap containing treatments, a comprehensive literature search of Embase, PubMed, the Clinicaltrials.gov (http://ClinicalTrials.gov/), and the Cochrane Library published up to August 2018 was conducted. The search terms included: “S-1”, “capecitabine”,“gastric cancer” ,“gastric carcinoma”, “gastric tumor”, or “stomach cancer”. We also screened the reference lists of review articles. Additional studies were also retrieved by handsearching of relevant journals. We exclusively included studies published in English and Chinese.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were selected according to the PRISMA statement.13 Clinical trials which met the following criteria were included:

- Randomized Phase II, III, and IV trials

- Adults with advanced gastric cancer and received S-1 and Cap containing treatments

- Sample sizes, events, and event rates were available for drug safety and efficacy.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) animal research; 2) reviews; 3) only have abstracts; 4) overlapping data; and 5) studies without risk ratio, OR, or HR with 95% CI.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two reviewers independently conducted the literature screening, data extraction, and quality assessment of the trials. A third reviewer intervened when reviewers disagreed until a consensus was reached. We extracted the following information from each article: first author’s name, year of publication, study type, disease type, number of patients, trial phase, treatment and control arms, the number of patients with 1-year OS, 1-year progression-free survival (PFS), objective response rate (ORR), and adverse events. If the studies did not provide the 1-year OS or PFS data, we estimated those values from the Kaplan–Meier curve by using Engauge Digitizer software. The quality of the methodology in prospective trials was assessed by the Jadad criteria.14 The quality of each trial was graded as high-quality trial (score ≥3) and low-quality trial (score ≤2). The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) criteria (http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp) were used to assess the quality of the methodology in retrospective studies (range 0–9 stars). The studies were classified as high quality if they scored ≥7 stars.

Statistical analysis

Data on patients with 1-year OS, 1-year PFS, ORR, and adverse events were extracted from all of the included trials; risk ratio and 95% CI were calculated to assess the association strength of these two regimens with outcomes. The Q statistic and I2 statistic were used to assess the heterogeneity. I2 >50% indicated statistically significant heterogeneity. The random-effect model was used in these meta-analyses for conservative statistics. A funnel plot was used to assess the publication bias. We also performed sensitivity analysis of the trials included in our meta-analysis to examine whether the results of the meta-analysis were robust. Begg’s adjusted rank correlation test15 and Egger’s regression test16 were used to assess the funnel-plot asymmetric. A statistical test with a P<0.05 was considered significant. STATA statistical version 12.0 was used to perform all the statistical analyses (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). All P-values were two-sided.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

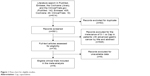

Our search yielded 614 potentially relevant clinical trials with S-1 and Cap containing treatment. After screening, eight primary clinical trials, which included 770 patients, met our inclusion criteria17–24 and were pooled for the meta-analysis (Figure 1). The characteristics of six RCTs and two retrospective trials are shown in Table 1. All trials included were open label, but all trials were of high-quality with Jadad score 3 or NOS score 8. According to the eligibility criteria of the majority of the trials, patients with impaired hepatic, renal, or bone marrow function were excluded and most of the patients had Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status scores of 0 or 1. This systematic review followed the guidelines of the PRISMA statement.

| Figure 1 Flow chart for eligible studies. |

Findings – 1-year OS, 1-year PFS, and ORR

A total of 669 Asian patients treated with S-1 or Cap containing treatment from seven trials were included for analysis of 1-year OS and 1-year PFS. As shown in Figure 2, the overall risk ratios of 1-year OS and 1-year PFS between S-1 and Cap containing therapies were 0.97 (95% CI: 0.84, 1.14, I2=0%) and 1.17 (95% CI: 0.83, 1.65, I2=0%), respectively. The results showed no statistical difference in 1-year OS and 1-year PFS between S-1 and Cap containing treatments (P=0.746 and 0.380, respectively).

A total of 770 Asian patients treated with S-1 or Cap containing treatment from eight studies were included for analysis of ORR. The ORRs in each trial were 40% vs 43%,18 29% vs 26%,19 41% vs 55%,20 44% vs 50%,21 42% vs 69%,22 28% vs 26%,23 51% vs 53%,24 and 46% vs 49%.17 As shown in Figure 2, the overall risk ratio of ORR between S-1 and Cap containing therapies were 0.85 (95% CI: 0.72, 0.99, I2=0%). The results showed that Cap containing treatment had a significantly better ORR than S-1-based therapy (P=0.043).

Findings – adverse events

Hematologic toxicities and HFS were adverse events of most concern for oral fluoropyrimidines, which always seriously affected the patients’ quality of life or interrupted the treatments. For these reasons, patients treated with S-1 or Cap containing treatment from eight studies were included for analysis of all-grade or grade 3–4 adverse events. In seven trials included in our manuscript, the incidence of neutropenia in each trial was 57% vs 62%,18 22% vs 28%,19 28% vs 20%,20 60% vs 73%,21 45% vs 65%,22 32% vs 33%,23 and 54% vs 60%.24 In six trials included in our manuscript, the incidence of HFS in each trials were 3% vs 25%,18 16% vs 56%,19 6% vs 30%,20 8% vs 46%,21 9% vs 40%,22 and 24% vs 57%.23 As shown in Table 2, the overall risk ratio of all-grade neutropenia and HFS between S-1 and Cap containing therapies were 0.85 (95% CI: 0.73, 0.99, I2=0%) and 0.29 (95% CI: 0.20, 0.40, I2=0%), respectively, and the results showed that S-1 containing treatment had a significant lower all-grade neutropenia and HFS incidence than Cap containing therapy (P=0.039 and P<0.001). Nevertheless, the results showed no statistical difference between S-1 and Cap containing therapies with regard to other related adverse events (P>0.05).

Sensitivity analysis

The results of sensitivity analysis of ORR, which included all eight trials, showed that no particular study affected the overall significance of the pooled estimates and that the results of the meta-analysis were robust (Figure 3).

| Figure 3 Sensitivity analysis of all clinical trials included. |

Publication bias

The shape of the funnel plot did not display any evidence of apparent asymmetry. Furthermore, the formal tests also showed no substantial publication bias (P=0.136 for the Egger’s test; P=0.174 for the Begg’s test) (Figure S1).

Discussion

Fluorouracil-based treatment is the most commonly used treatment for advanced gastric cancer. Several orally active fluorouracils (such as S-1 and capecitabine) are available, which, as single agents, are associated with response rates as high as 41%.8–10,19,25–28 As a substitute for continuous 5-FU infusion, S-1 or Cap plus platinum are recommended for advanced gastric cancer patients in Asia. But until now, no definitive conclusion about which regimen was better for patients with advanced gastric cancer could be reached. Here, we performed a systematic review on the efficacy and safety of S-1 and Cap containing regimens in advanced gastric cancer based on eight clinical studies, which included 770 subjects. Our results indicated that: 1) Cap containing treatment showed significantly better ORR than S-1-based regimen, but there was no statistical difference in 1-year OS and 1-year PFS between S-1 and Cap containing regimens; 2) S-1 containing treatment showed significantly lower incidence of all-grade neutropenia and HFS than Cap containing therapy, but there was no statistical difference in other adverse events between S-1 and Cap containing regimens.

The results of this review partially agreed with those reported by Veer et al.12 In that meta-analysis, the results indicated that S-1 had similar efficacy compared to Cap, but was associated with a lower incidence of grade 1–2 HFS and grade 3–4 neutropenia. However, only three RCTs were included, which might contribute to the different results than the findings of our study. Our study included more relevant articles; although the number of trials was still small, our findings might stimulate further investigations.

OS, PFS, and ORR are the most commonly studied outcomes for determining the efficacy of a treatment. The results of the meta-analysis of the number of patients having on-study ORR showed that Cap might have superiority than S-1 in ORR. As we know, if the differences in actual ORR were <5%, the clinical relevance would be small. But these data were not consistent, as the differences in actual ORR were <5% in some trials, whereas they were not in others. So we pooled the overall risk ratio, which was found to be 0.85 (P=0.043). The results showed that, till date, S-1-based treatments had significantly better ORR than Cap-based regimens, but we still need more high-quality RCTs to confirm this conclusion. 1-year OS and 1-year PFS results showed no evidence of difference between these two arms. As we know, OS and PFS results are much more important than ORR to evaluate the efficacy, and Cap containing treatment showed superiority only in ORR but not OS or PFS, thus a definite conclusion could not be made about the better efficacy in Cap containing arms.

Adverse events of chemotherapy regimens were of great concern for clinicians and clinical pharmacists. Hematologic toxicities and HFS are most common adverse events of fluoropyrimidines, which always seriously affected the patients’ quality of life and interrupted the treatments. A meta-analysis showed that S-1 had lower incidence of grade 1–2 HFS and grade 3–4 neutropenia.12 Another meta-analysis focused on both advanced gastric cancer and metastatic colorectal cancer, which showed that S-1 had a significant lower incidence of grade 3–4 HFS than Cap (P<0.001).29 But in our study, the results showed that S-1 containing treatment had lower incidence of all-grade neutropenia and HFS than Cap-based therapy, although there was no significant difference in other adverse events. This finding suggested that for some patients with higher risk of myelosuppression or HFS, S-1 containing treatment might be a better choice than Cap-based therapy. Heterogeneity was an important concern in meta-analysis. The heterogeneity might not be totally ruled out in this study, so the sensitivity analysis was used to identify the robustness of our findings. The results displayed that no study affected the overall significance of the pooled estimates, and the results of our findings were robust. Publication bias might introduce false-positive results in meta-analysis.16 To avoid the possible bias, all the studies included were properly assessed. Egger’s and Begg’s tests were performed for detecting publication bias and no evident bias was found. The results of publication bias and sensitivity analysis indicated that conclusions of our study were credible.

As several limitations merit consideration, the present meta-analysis should be interpreted with caution. First, the number of studies was still small, especially due to the lack of more high-quality RCTs. Second, the schedule and dosage of S-1 and Cap containing treatments in all eight studies included in this review were not consistently used. Although it was often not possible to investigate to what extent dose or schedule differences might have influenced the results, we still need more rigorously designed experiments. Third, the eight studies in our analysis were open label, which might affect the outcomes. Fourth, patients included in all studies were from Asia, so the conclusions should be made with caution for Western populations.

Conclusion

For Asian patients, Cap containing treatment may have superiority in ORR but shows higher incidence of all-grade neutropenia and HFS compared with S-1-based therapy. There appears to be no statistical difference in 1-year OS, 1-year PFS, and incidence of other adverse events between S-1 and Cap containing treatments.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province, China (grant number LYY18H310002) and the Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 81872213).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Allemani C, Matsuda T, di Carlo V, et al. Global surveillance of trends in cancer survival 2000–2014 (CONCORD-3): analysis of individual records for 37 513 025 patients diagnosed with one of 18 cancers from 322 population-based registries in 71 countries. Lancet. 2018;391(10125):1023–1075. | ||

Wagner AD, Grothe W, Haerting J, Kleber G, Grothey A, Fleig WE. Chemotherapy in advanced gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis based on aggregate data. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(18):2903–2909. | ||

Glimelius B, Ekström K, Hoffman K, et al. Randomized comparison between chemotherapy plus best supportive care with best supportive care in advanced gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 1997;8(2):163–168. | ||

Murad AM, Santiago FF, Petroianu A, Rocha PR, Rodrigues MA, Rausch M. Modified therapy with 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and methotrexate in advanced gastric cancer. Cancer. 1993;72(1):37–41. | ||

Wagner AD, Syn NLX, Moehler M, et al. Chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;23(24):CD004064. | ||

Pyrhönen S, Kuitunen T, Nyandoto P, Kouri M. Randomised comparison of fluorouracil, epidoxorubicin and methotrexate (FEMTX) plus supportive care with supportive care alone in patients with non-resectable gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 1995;71(3):587–591. | ||

Schöffski P. The modulated oral fluoropyrimidine prodrug S-1, and its use in gastrointestinal cancer and other solid tumors. Anticancer Drugs. 2004;15(2):85–106. | ||

Shirasaka T, Shimamato Y, Ohshimo H, et al. Development of a novel form of an oral 5-fluorouracil derivative (S-1) directed to the potentiation of the tumor selective cytotoxicity of 5-fluorouracil by two biochemical modulators. Anticancer Drugs. 1996;7(5):548–557. | ||

van Groeningen CJ, Peters GJ, Schornagel JH, et al. Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of oral S-1 in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(14):2772–2779. | ||

Boku N, Yamamoto S, Fukuda H, et al. Fluorouracil versus combination of irinotecan plus cisplatin versus S-1 in metastatic gastric cancer: a randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(11):1063–1069. | ||

Okines AF, Norman AR, Mccloud P, Kang YK, Cunningham D. Meta-analysis of the REAL-2 and ML17032 trials: evaluating capecitabine-based combination chemotherapy and infused 5-fluorouracil-based combination chemotherapy for the treatment of advanced oesophago-gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(9):1529–1534. | ||

Ter Veer E, Mohammad NH, Lodder P, et al. The efficacy and safety of S-1-based regimens in the first-line treatment of advanced gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19(3):696–712. | ||

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339(jul21 1):b2535. | ||

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12. | ||

Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–1101. | ||

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. | ||

Wan Y, Hui H, Wang X, Wu J, Sun S. [Comparison of the efficacy and safety of capecitabine or tegafur, gimeracil and oteracil potassium capsules combined with oxaliplatin chemotherapy regimens in the treatment of advanced gastric cancer]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2016;38(1):28–34. Chinese. | ||

Kim GM, Jeung HC, Rha SY, et al. A randomized phase II trial of S-1-oxaliplatin versus capecitabine-oxaliplatin in advanced gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(4):518–526. | ||

Lee JL, Kang YK, Kang HJ, et al. A randomised multicentre phase II trial of capecitabine vs S-1 as first-line treatment in elderly patients with metastatic or recurrent unresectable gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;99(4):584–590. | ||

Seol YM, Song MK, Choi YJ, et al. Oral fluoropyrimidines (capecitabine or S-1) and cisplatin as first line treatment in elderly patients with advanced gastric cancer: a retrospective study. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2009;39(1):43–48. | ||

Shitara K, Sawaki A, Matsuo K, et al. A retrospective comparison of S-1 plus cisplatin and capecitabine plus cisplatin for patients with advanced or recurrent gastric cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2013;18(3):539–546. | ||

Nishikawa K, Tsuburaya A, Yoshikawa T, et al. A randomised phase II trial of capecitabine plus cisplatin versus S-1 plus cisplatin as a first-line treatment for advanced gastric cancer: Capecitabine plus cisplatin ascertainment versus S-1 plus cisplatin randomised PII trial (XParTS II). Eur J Cancer. 2018;101:220–228. | ||

Kim M-J, Kong S-Y, Nam B-H, Kim S, Park Y-I, Park SR. A randomized phase II study of S-1 versus capecitabine as first-line chemotherapy in elderly metastatic gastric cancer patients with or without poor performance status. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2018;28(1):23–30. | ||

Kawakami H, Takeno A, Endo S, et al. Randomized, open-label phase II study comparing capecitabine-cisplatin every 3 weeks with S-1-cisplatin every 5 weeks in chemotherapy-naive patients with HER2-negative advanced gastric cancer: OGSG1105, HERBIS-4A Trial. Oncologist. 2018;23:1411–e147. | ||

Hong YS, Song SY, Lee SI, et al. A phase II trial of capecitabine in previously untreated patients with advanced and/or metastatic gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(9):1344–1347. | ||

Koizumi W, Saigenji K, Ujiie S, et al. A pilot phase II study of capecitabine in advanced or recurrent gastric cancer. Oncology. 2003;64(3):232–236. | ||

Lee S-J, Cho S-H, Yoon J-Y, et al. Phase II study of S-1 monotherapy in paclitaxel- and cisplatin-refractory gastric cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;65(1):159–166. | ||

Jeung H-C, Rha SY, Shin SJ, et al. A phase II study of S-1 monotherapy administered for 2 weeks of a 3-week cycle in advanced gastric cancer patients with poor performance status. Br J Cancer. 2007;97(4):458–463. | ||

Zhang X, Cao C, Zhang Q, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of S-1-based and capecitabine-based regimens in gastrointestinal cancer: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1):e84230. |

Supplementary material

| Figure S1 Publication bias risk. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.