Back to Journals » Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare » Volume 11

Should frail older adults be in long-term care facilities?

Authors Sørbye LW, Sverdrup S, Pay BB

Received 27 October 2017

Accepted for publication 9 December 2017

Published 2 February 2018 Volume 2018:11 Pages 99—107

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S155372

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Liv Wergeland Sørbye, Sidsel Sverdrup, Birgit Brunborg Pay

Institute of Nursing and Health, VID Specialized University, Oslo, Norway

Aim: Home-based nursing care is relatively easy to access in Norway compared to the rest of Europe, and the threshold for applying for assistance is relatively low. The aim of the present study was to analyze factors that enable frail older adults to live in their own homes, with a low level of care burden stress.

Methodology: In 2015 and 2016, eight municipalities from different parts of Norway participated in a cross-sectional study. The quantitative part of the project consisted of assessing care of 71 older adults, aged ≥80 years, using a geriatric comprehensive assessment. The qualitative part consisted of semistructured telephone interviews with 14 leaders of nursing homes and home-based nursing care and interviews with 26 close relatives.

Results: In this sample, 60% of the older adults were living alone, and 79% were at risk of permanent nursing home admission; 31% stated that they would be better-off at a higher caring level, mainly due to living alone. The relatives, their resources, and motivation to provide care seemed to be crucial for how long older adults with heavy care burden could stay at home. The municipalities offered a combination of comprehensive home care, day centers, and revolving short-term stays to enable them to live at home.

Conclusion: The results reveal that the need for home care services is steadily increasing. The relatives are coping with the physical care, far better than the uncertainties and worries about what could happen when the older adults stay alone. The number of beds in institutional care in each municipality depends on various factors, such as the inhabitants’ life expectancy, social aspects, geography, well-functioning eldercare pathways, competence of the health professionals, and a well-planned housing policy.

Keywords: home care, geriatric assessment, organization, long-term care facilities, next of kin experiences

Introduction

Home-based nursing care is relatively easy to access in Norway compared to other European countries, and the threshold for applying for assistance is low.1 During the last 10–15 years, the employment level has been high, and the workforce has increasingly included female workers. The Nordic welfare-political model ranks institutional care as the gold standard for elderly care. As the other Nordic countries started to reduce the number of beds in traditional long-term care facilities in the 1990s, Norway continued to expand.2 The Norwegian government has claimed that older adults have a legal right to access a bed in long-term care facilities or a similar nursing care home designed for 24-hour coverage. However, this is an ambition that will demand too many economical resources and available carers.3 An ongoing discussion is whether institutional care benefits the majority of older adults, or if they would be better-off in their own homes.4 In Norway, the public spending on long-term care (health and social components) is 2.4% of gross domestic product.5 The communities organize the following home care services: nursing and other health services (40%), practical help (20%), training (30%), and personal assistance (10%).6 The receivers only pay a low share according to their pensions. The allocation of home services should therefore be distributed based on the discretion of family and health care providers in order to reduce potential harms for the older adults. Taking care of a frail, older adult may cause challenges for both their next of kin and the health services.7 Assessing cognitive deficits is more complicated than testing physical condition.8 Both nationally and internationally, there is a strong faith in “innovation” and “smart house technology”. However, for people with dementia, many modern technologies make it difficult to cope with daily life. Telecare can be both a help and a hindrance. One has to consider a person’s need for it, as well as ethical issues in each case.9

The aim of the present study was to analyze conditions that enable frail older adults to live in their own homes, to explore how home care services provided care for those who wished to stay in their own homes, and the next of kin’s experiences with home care services. The main research question posed was which challenges municipalities and next of kin experience in caregiving of frail older adults.

Methods and materials

Both quantitative and qualitative methods were used in the study.

The municipalities that were included were selected on the basis of the following principles: geographic spread and distribution between institution and housing care. An invitation letter was mailed to the health care administration of 40 municipalities, of which 30 were approved to participate.4 This study included eight of these municipalities which reflected the whole sample. The concern was the health status of the older adults and the interaction between the home care nurse and next of kin. The leader of the home care apartments selected nurses involved in daily care of the older adults. The nurses contacted those who were defined by the staff and the next of kin to be on the borderline between home care or institutional care. The authors received contact information of the actual nurses. The different municipalities were visited, and they went through each of the assessments together with the actual nurse, ensuring that all definitions and variables were understood correctly according to the questions.

The authors had to depend on the home care leaders’ judgment about the selection of our target group. In the main study, 56 older adults were included. Fifteen more adults were from two of our catchment areas during early fall 2016. The leaders stated that they had no more-risk older adults. The saturation point was reached.

The next of kin were asked to participate in an interview with one of the researchers. Those who agreed signed with their name and telephone number on a separate informed consent. The administration in the actual municipalities obtained contact information for actual leaders of nursing homes and home-based nursing care.

The research protocol was approved by the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics (reference number: 2015/1925 B). Ethical consideration was according to national regulations. The older adult and the next of kin signed a written informed consent. The project was rooted in the national organization of the municipalities. The nurses and the researchers were aware of their responsibilities according to ethical guidelines.

All interviews were conducted in Norwegian and the responses were translated to English by the authors, with the assistance of a professional editor.

Quantitative data

The quantitative part of the study considered assessments of caring needs for 71 older adults (age ≥ 80 years) with comprehensive disabilities. The nurses assessed care burden stress on relatives when they experienced one of the following expressions: the caregiver was unable to continue care, the caregiver experienced insufficient support, or the caregiver expressed unease. Despair and concern about whether the older adult would be better-off living in another environment were coded as a positive response.10

The data were collected by the assessment tool Resident Assessment Instrument (RAI) for Home Care (RAI-HC, interRAI version 2.0). The RAI instrument has been translated and back-translated, with good content and face validity and interobserver reliability.1 The instrument includes >300 items derived from the literature. The items evaluate various factors (sociodemographic background, functional status, cognitive abilities, morbidity, symptoms, social contacts, communication, and formal and informal help) and the utilization of services and treatments.

The different variables of the RAI-HC are expressed in an algorithm that characterizes care burden: Methods for Assigning Priority Levels (Maple). The Maple algorithm includes cognitive functioning, activity of daily living (ADL), instrumental activity (IADL), stays in institutions during the last week, states of confusion, behavioral problems, falls, and overall decline in general condition.11 Other variables are fecal incontinence (less than once over the last 3 days), weight loss of ≥5% in the last 30 days or ≥10% in the last 180 days, and body mass index. The selection of variables was based on theoretical considerations and experiences in other publications using interRAI for home care assessment. Current health status was assessed using several scales generated in the analysis tool RAIsoft. Changes in health status, illness, and symptoms were determined by the Changes in Health, End-stage disease and Symptoms and Signs (CHESS) scale.12 The depression rating scale (DRS) was used as a marker of depression.13 For assessment of cognitive function, the cognitive performance scale (CPS2) is a 7-point scale composed of memory, communication skills, ability to manage own medications, and ability to manage personal finances; a score of ≥4 indicates moderate to severe cognitive impairment.14

Descriptive statistics and statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 23. Health status was assessed statistically using uni- and bivariate methods. Chi-square analysis was used to test characteristics and clinical features associated with dichotomous variables. Algorithm was generated in the analysis tool RAI software (www.raisoft.fi). The data were collected in 2015/2016 (N=71).

Qualitative data

Semistructured interviews were conducted in order to obtain information from the next of kin. The intention was to add important information about their situation, focusing on care-burden stress and factors that are important for delaying a permanent nursing home admission. The main concern was to understand the health policies in the different municipalities and how services were provided. Eight leaders of nursing homes and seven leaders of home-based nursing care participated.

The interview guide for the next of kin (N=26) was based on experiences from interRAI and was designed to add important information about their situation, focusing on care-burden stress.

Qualitative descriptive study like this has value in presenting and treating research factors such as living entities that resist simple classification.15 The present study intended to reveal what types of living the municipalities offered the frail older adults and to what degree the quality and content of care was tailored to the patients’ physical and psychosocial needs. Focus was on the following main topics: 1) practice and the main reasons for admission to nursing homes, 2) the extent of formal and informal support before admission, 3) the levels of cognitive and clinical functioning, and 4) efforts required to ensure living at home and to prevent institutionalization. The interviews were carried out by telephone. The interviewers made notes during the interview and transcribed the full text immediately. In the process of data analyses, the experiences of relatives were categorized as supplement to the structured questions. A descriptive qualitative design was used to interpret and discuss the data.16 First, the authors read and re-read the interviews several times in order to grasp the meaning of the material as a whole. In the second phase, the interviews were re-read closely with the purpose of the study in mind, and the text was divided into meaningful units. The units were studied and compared in order to discover similarities and differences between the informants’ experiences, as well as essential aspects of next of kin and caregiver experiences.

Results

Quantitative results

The average age of the 71 participants was 87.0 years, of those 68% were female. The patient characteristics are reported in Table 1.

| Table 1 Patient characteristics (N=71) Abbreviations: CHESS, Changes in Health, End-stage disease and Symptoms and Signs; max, maximum; min, minimum; Mn, mean; SD, standard deviation. |

Approximately 60% of the older adults lived alone and 40% with their spouses in their homes. The whole group was characterized by clinically complex diagnosis and reduced physical functioning; yet, roughly half of them had relatively stable health conditions due to adequate medication. The care complexity was relatively high. The risk of undernutrition was higher, followed by obesity. Most of the older adults were satisfied with their medical treatment for pain. Approximately 20% preferred revolving short-term stays and 30% had stays that were more sporadic. In this sample, 79% were at risk of permanent nursing home admission, and half of them were in need of a high or very high level of care (Table 1).

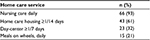

The amount of formal support is described in Table 2.

| Table 2 Formal support (N=71) |

Home care housing mainly consists of cleaning the house and other kinds of housework provided 1.5 hours every third week by the municipality or a private agency. On average, they received 9 hours of home-based nursing care every week. Approximately half of them used a day center 2 days a week.

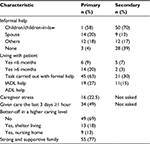

The main caregivers were children or children-in-law. Six of the older adults had a child moving in with them the last 6 months. The family caregivers helped with IADL functioning. On average, they had used 4.7 hours of caring during the last 3 days (Table 3).

| Table 3 Caregiver characteristics (N=71) Abbreviations: ADL, activity of daily living; IADL, instrumental activity. |

Qualitative results

Leaders in the municipalities emphasized that home-based care was provided in order to enable the older adults to continue to live in their homes. To what extent this approach is successful often depends on resources on both structural and individual levels. The leaders highlighted that a caring culture consisting of collaboration, user participation, and self-efficacy is important. Three factors at the individual level were particularly important to maintain living at home: family, network, and lease of life. Leaders emphasized that married couples could live longer in their own homes if one or both spouses had a certain level of functioning or were able to compensate for each other’s weaknesses. If some of these factors fail, they said that a situation would arise in which nursing home placement may be needed. Persons admitted to nursing homes are usually frail and in great need of care.

Regarding preventive health services in order to maintain a certain level of self-care and user cooperation, some of the municipalities offered training facilities and social activities at day-care centers. In such establishments, volunteers initiate these activities and prepare meals that the older adults can buy and eat in a social setting.

Overall, the participants assumed that it was better for the older adults to have the opportunity to stay in their homes as long as possible. However, this requires well-developed and organized home care services and multidisciplinary competence. They also claimed that most people who were in need of assistance were identified by the services. However, in some cases, home care professionals should empower the older adults to apply for extended services. Leaders indicated that the amount of home care an older adult can receive is almost unlimited. A variety of services are commonly offered before admission, including short-term stays in nursing homes and extensive home care services. Leaders reported that successful allocation of older adults depends on a good balance between economy, quality, and cooperation between various organizational units.

Factors that require long-term care facilities

Most nursing home residents had a huge need for assistance before admission. Interviews with leaders revealed that home-dwelling residents often had significant and complex issues and that those permanently placed in nursing homes were in great need of care and unable to take care of themselves, despite extensive nursing care support. Frequent causes of hospitalization were different kinds of impairments due to falls, cognitive deficits, and impaired ADL. Emergencies often occurred, such as a spouse who became ill or had an accident and was unable to take care of the home situation. Residential care was mainly offered for the same reasons as the nursing home. These older adults had less need for assistance, but they needed to feel safe in their residence.

Care burden

The health situations of relatives other than spouses were also important. Their resources and motivation to provide care seemed to be crucial for how long older adults with heavy care burden could stay at home. In some cases, short-term stay in nursing homes was a solution. One spouse said: “I am very pleased to combine alteration of stays. This gives me freedom and allows me to rest.”

Relatives were generally satisfied with the home care services. They indicated that disabled older adults have access to the special equipment they need; they felt that the older adults had a good life in their own homes even though they spent much time alone. They were concerned that an acute change might occur, even though all in need of a safety alarm had received one from the health care service. Furthermore, some respondents emphasized that next of kin were the only persons who had an overview of the older adult’s total situation. They expressed that many different actors from the home care services were involved in daily care of their loved ones and that none of them had a complete overview of the situation. The relatives expressed that it felt like a burden to constantly deal with all the various people who “invaded” their home, even into the most private of all spaces, the bedrooms, and bathrooms. The spouses emphasized that the patient was the center of the home services’ benefits and that they had to be statists in the background putting everything in order. The relatives underlined that several of the nurses had no information about the actual situation. Many families found this difficult and challenging. Several relatives expressed the desire for one responsible nurse or smaller teams of persons who knew the older adult. One daughter expressed:

Everything happens so fast. The nurse helps mother into the bathroom, runs to the kitchen to prepare a meal, then back to the bathroom to accompany mother to the dining table. There is no time to chat. When I asked if she would return the following day, she did not know because the schedules with working lists were not announced until the next morning.

Many nurses were part-time workers, and several did not speak proper Norwegian. This made cooperation challenging and the relatives felt insecure.

Several of the older adults had appointments with different kinds of health specialists. This was not always coordinated with the home care services. Relatives expressed that they would like to receive a weekly schedule including information about the home carers, name and phone number, appointments, and a brief description of the individual’s specific tasks. They said that if the services were well prepared and performed, there would probably be less need for homes with a higher level of care.

Relatives of patients who had primary and secondary contacts in the home care service expressed satisfaction. However, many spouses felt that they were homebound and expressed that they wished they could have a permanent visitor who could assist them, so that they could feel free to leave the house once in a while.

I am very fond of my spouse, but it feels like being at work 24 hours a day. My spouse is at home instead of staying in an institution. This means a lot to me, too. Good to be able to be helpful to my husband. [Spouse respondent 1]

Being dependent is almost like having house arrest. I can hardly leave the house when my husband is at home. I can only be away for one hour before I have to return to assist him, eg, to the toilet. [Spouse respondent 2]

Cooperation and organization

The leaders described great variation in how care tasks were assessed and organized. Most of the municipalities had allocation offices that handle written or oral requests for care. The allocation offices ensured that investigations and assessments of user requirements were carried out, allowing them to offer appropriate services to the users. A leader stated that an external review concluded that they had a well-organized practice:

We try to see quality, economy, and capacity in context. As a municipality, we are responsible for an appropriate use of the available funds. I feel that we have a good balance of different interests and feel no need to change practice.

In some municipalities, all inquiries about care were directed toward leaders for home-based services, who ensured that they were handled and assessed by nurses in executive service. Sometimes, a short-stay nursing home was used to observe the current user over time in order to provide the appropriate help. This information could provide either a long-term place in a nursing home or more comprehensive home care services to enable the person to continue living at home. Some nursing homes had waiting lists, but if urgent situations occur, older adults with the most expressed needs would be prioritized.

The interviews pointed out that the municipalities searched for a unified practice, but they also required a certain level of discretion and urgent solutions. This made it almost impossible to establish unambiguous criteria in advance. Some informants argued that it is necessary to continue working on criteria that can make user needs more predictable for both health professionals and citizens. In municipalities where the nurses had the authority to make decisions, a second opinion was rarely needed. The nurses claimed that this model worked in practice and that those who needed help were identified. This required proximity and confidence building toward the potential users:

Confidence building in connection with applications for more and expanded assistance is important, particularly toward people who are reluctant to demand anything for themselves.

In several municipalities, arguments from managers and potential users often determined the allocation of nursing homes. Economic conditions were emphasized, and some leaders said that it is necessary to consider a nursing home bed if assistance in the home was more expensive. Nevertheless, exceptions were made when users and their families wanted change. If there was a need to change the level of care, then it was discussed in municipality meetings between the leaders of the services.

Leaders in the home care services expressed a desire for more continuity in monitoring the older adults, structures for health care prevention, and rehabilitation in ADL. In some of the municipalities, the primary contacts conduct annual interviews with users in which they map their health status, satisfaction with services, and needs for change.

Discussion

This study contributes information that is essential to enable frail older adults to live longer in their own homes. The authors paid particular attention to how the home care services provide caregiving for older adults, as well as the next of kin’s experiences with the home care services. Both are of crucial importance with respect to this kind of caregiving.

An important health policy ideology in Europe is that older adults should be enabled to live at home as long as possible and have the shortest possible stay in an institution before they die.17 In Norway, this has led to a situation in which the number of home care services have increased faster than competence building and quality assurance. However, the length of stays in acute hospitals has decreased. Approximately 50% end their lives in nursing homes.18

The older adults’ health care needs

In Norway, females live ~6 years longer than males19 and comprise >70% of residents enrolled in long-term stays in institutions.20 In this study, male and female were about the same age. More females were able to care for their husbands, and few men lived alone. When females required 24/7 care, problems arose because they usually lived alone.

According to CHESS scores, two-thirds of the older adults in this study had unstable health conditions. They were vulnerable, and their situations might change abruptly if one of the spouses was admitted to the hospital or was unable to manage their ADL. When changes occur, problems that have been compensated for by a spouse may become evident because of a long-term interdependency in the couple. The “healthy” spouse’s affections for the other spouse can lead to extending their own limits. This study showed that not only the older adult but also the spouse have to adjust to the home carers’ routines. They felt that they had to be ready in the morning to receive the home care staff even though they occasionally wanted to sleep a little longer.

Symptoms and functional impairment that may require a nursing home include dementia, heart failure, respiratory failure, and chronic obstructive lung disease requiring a respirator. The same applies to various forms of cancers with medical treatment. Older adults usually find it difficult to manage medication, even though the home care services assist them.21 Inadequate nutrition is another serious challenge. Lack of sufficient meals is not an economic problem in Norway, but an issue related to quality of life.22 To prepare meals and eat alone rarely stimulates the appetite. Low body mass index and unintended weight loss are warning signs.23 In our cohort, the relatives were concerned about the home care service who had time to prepare food for the relatives, but not to assist during the meal. Several of the older adults were homebound; they received proper medical and nursing care, but were disabled to take part in social activities. In home care, unmet needs are mainly related to social activities.24 Loneliness and risk of depression may reduce the feelings of closeness and compassion. For older adults living alone, a lack of opportunities to express negative feelings and receive love is another challenge.25 Despite extensive home care and supervision from relatives, 30% of the older adults were alone >8 hours a day. Their relatives were often concerned that adverse events might occur during these hours, in situations where the older adults were unable to call for help. This was related to the fact that roughly half of the samples in this study were unable to make a phone call.

Health professionals should be aware of signs of depression when planning interventions.

All these conditions enhance the need for help. If negative living conditions increase in complexity, the situation will be unmanageable in the long run, even with sufficient home care.

Next of kin’s care and need for relief

This study supports that living together with a spouse/partner reduces the prevalence of loneliness across Europe.26,27 Further that next of kin were far more comfortable with assisting their relatives with IADLs than with personal care, such as urinary and fecal incontinence.28,29 Safety fire alarms should be available for patients at risk of falling,30 but this might create a false sense of security if the person is unable to use them. Therefore, the home care nurses should demonstrate to the older adult how to activate the alarm at least once a month. In this study, almost half of them required a facilitator or assistance using the telephone. One needs to keep in mind that those who have a problem using a mobile telephone most likely have difficulties using other kinds of equipment when an emergency occurs. Few of them used telecare due to frailty and high age. These findings, based on RAI-HC as well as on open-ended interviews with caregivers, are in accordance with other studies.31 A strong correlation was found between the relatives’ signs of stress and their desire that the user received more extensive home care or a higher level of care as a resident. The relatives expressed lack of predictability. Our results support that the involvement and collaborative process between health professionals, older adults, and relatives has practical significance for health care services.32

Holistic organization of health care services

In the Nordic countries, the welfare model is universalistic. Home care is publicly financed and given independently of the patients’ income.33 However, each municipality has to create the priorities for their own health budget. A long-term care bed is far more expensive than home care. Accordingly, health care prevention and rehabilitation activities should be implemented in home-based nursing care as fast as possible, in order to prevent accelerating disabilities and hospitalization as claimed by the government.

Municipalities with a low degree of coverage of long-term care facilities are expected to have a well-developed and well-functioning domestic service. However, this is not necessarily the case. It depends on how the services are organized and what kinds of aggregated demands they prioritize. National guidelines encourage the municipalities to aim toward users of care services being able to live a dignified life at home, alone, or with coping support as long as possible. The next of kin expressed that it was difficult for the oldest to get sufficient everyday rehabilitation in regular home care. A reviewed article described several types of rehabilitation, intervention task that could reduce the level of frailty among municipality-dwelling older adults. In general, they found that activity had a documented effect.34 A cross-sectional survey revealed that the level of competence among health care professionals was insufficient in the following areas: nursing measures, advanced procedures, and nursing documentation.35 A comprehensive geriatric assessment gives important data about the older adults’ health conditions.36 However, this has to be compared with the health condition of the next of kin.

Today, housing solutions are adapted for use of new welfare technology within the private area. The politicians hope this could reduce the need of home care service. However, a devoted next of kin will remain important.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study were that the home care nurses assessed older adults using the RAI instrument and asked for additional information if their experiences and written documentation were inadequate. Also, the relatives expressed their experiences with older adult’s situation. A limitation of the study is the small sample in the quantitative study. Also, the older adults were not interviewed, but nurses and relatives have assessed their needs based on their knowledge. However, this might be seen as a strength, since a number of problems were revealed, based on the experiences from those who were closest to the burdens. Due to triangulation, this study has revealed the need for more research related to how social–political challenges and problems on an individual level might be addressed in the future.

Conclusion

Care for older adults varies across municipalities in Norway. Next of kin are (or were) satisfied with the home care services. They give (or gave) extensive practical care for their relatives, when they are (or were) able to do so. However, this study highlights a number of remaining challenges related to both content and organization of home care services, as well as the care-burden stress among relatives. Technological equipment alone is not the solution; future research needs to examine this more closely to achieve the social political goals.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the persons who participated and shared their experiences with us and leaders in the community services for recruiting participants. The main project was sponsored by the National Organization of the Municipalities, report number R9342. VID Specialized University sponsored LWS, SS, and BBP in the extension of the study.

Author contributions

LWS, SS, and BBP participated in the design of the study together with Agenda Kaupang on the behalf of the Norwegian Association of Local and Regional Authorities. All authors contributed toward data analysis and interpretation, drafting and critically revising the paper, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Carpenter I, Gambassi G, Topinkova E, et al. Community care in Europe. The Aged in Home Care Project (AdHOC). Aging Clin Exp Res. 2004;16(4):259–269. | ||

Rostgaard T, Szebehely M. Changing policies, changing patterns of care: Danish and Swedish home care at the crossroads. Eur J Ageing. 2012;9(2):101–109. | ||

NOU 2014:12. Åpent og rettferdig- prioriteringer i helsetjenesten [Open and Fair – Priorities in the Health Service]. Available from: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/NOU-2014-12/id2076730/sec1. Accessed November 21, 2017. Norwegian. | ||

Sørbye LW, Schanche P, Sverdrup S, Brunborg BP. Heldøgns omsorg – kommunenes dekningsgrad. Færre institusjonsplasser, mer omfattende hjemmetjenester [24-Hour Care – Municipalities Coverage Ratio. Fewer Institutions, More Comprehensive Home Care Services]. Oslo: VID-vitenskapelige høgskole; 2016. Available from: http://www.ks.no/contentassets/561a8995275743818438eafe990cd57c/r9342-ks-heldogns-omsorg-080416docx.pdf. Accessed November 21, 2017. Norwegian. | ||

OECD. Health Statistics 2017. Available from: http://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/long-term-care.htm. Accessed November 21, 2017. | ||

Kjelvik J, Jønsberg E. Botid i sykehjem og varighet av tjenester til hjemmeboende [Length of stay in nursing home and homecare services]. Samdata; 2017:2. Available from: https://helsedirektoratet.no/Documents/Statistikk%20og%20analyse/Samdata/Filer%20til%20WEB_Dundas/2017%20Analysenotater/2017-02%20Botid%20i%20sykehjem%20og%20varighet%20av%20tjenester%20til%20hjemmeboende.pdf. Accessed November 21, 2017. Norwegian. | ||

Shiba K, Kondo N, Kondo K. Informal and formal social support and caregiver burden: the AGES caregiver survey. J Epidemiol. 2016; 26(12):622–628. | ||

Garcia-Ptacek S, Modeer IN, Kareholt I, et al. Differences in diagnostic process, treatment and social support for Alzheimer’s dementia between primary and specialist care: results from the Swedish Dementia Registry. Age Ageing. 2017;46(2):314–319. | ||

Dewsbury G, Ballard D. Telecare: a reactive service to enhance patient care. Br J Nurs. 2013;22(7):364. | ||

Mello JA, Macq J, Van Durme T, et al. The determinants of informal caregivers’ burden in the care of frail older persons: a dynamic and role-related perspective. Aging Ment Health. 2017;21(8):838–843. | ||

Hirdes JP, Ljunggren G, Morris JN, et al. Reliability of the interRAI suite of assessment instruments: a 12-country study of an integrated health information system. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:277. | ||

Hirdes JP, Frijters DH, Teare GF. The MDS-CHESS scale: a new measure to predict mortality in institutionalized older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(1):96–100. | ||

Burrows AB, Morris JN, Simon SE, Hirdes JP, Phillips C. Development of a minimum data set-based depression rating scale for use in nursing homes. Age Ageing. 2000;29(2):165–172. | ||

Morris JN, Howard EP, Steel K, et al. Updating the Cognitive Performance Scale. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2016;29(1):47–55. | ||

Sandelowski M. What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33(1):77–84. | ||

Turjamaa R, Hartikainen S, Kangasniemi M, Pietila AM. Living longer at home: a qualitative study of older clients’ and practical nurses’ perceptions of home care. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(21–22):3206–3217. | ||

Romøren TI, Torjesen DO, Landmark B. Promoting coordination in Norwegian health care. Int J Integr Care. 2011;11(Spec 10th Anniversary Ed):e127. | ||

The Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH) . Place of Death; 2016; Table D3. Available from: http://statistikkbank.fhi.no/dar/. Accessed December 15, 2017. | ||

Statistics of Norway. Life Expectancy. 2017. Available from: http://www.ssb.no/dode. Accessed November 21, 2017. | ||

Ramm J. Eldres bruk av helse og omsorgstjenester [Elderly Use of Health and Care Services]. 2013: SSB. Available from: https://www.ssb.no/helse/artikler-og-publikasjoner/_attachment/125965?_ts=13f8b5b6898. Accessed November 21, 2017. Norwegian. | ||

Elliott RA, Lee CY, Beanland C, Vakil K, Goeman D. Medicines management, medication errors and adverse medication events in older people referred to a community nursing service: a retrospective observational study. Drugs. 2016;3(1):13–24. | ||

Sørbye LW, Schroll M, Finne Soveri H, et al. Unintended weight loss in the elderly living at home: the aged in Home Care Project (AdHOC). J Nutr Health Aging. 2008;12(1):10–16. | ||

Morris JN, Howard EP, Steel K, et al. Predicting risk of hospital and emergency department use for home care elderly persons through a secondary analysis of cross-national data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:519. | ||

Turcotte PL, Lariviere N, Desrosiers J, et al. Participation needs of older adults having disabilities and receiving home care: met needs mainly concern daily activities, while unmet needs mostly involve social activities. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:95. | ||

Halvorsrud L, Kalfoss M. Exploring the quality of life of depressed and nondepressed, home-dwelling, Norwegian adults. Br J Community Nurs. 2016;21(4):172–177. | ||

Sundstrom G, Fransson E, Malmberg B, Davey A. Loneliness among older Europeans. Eur J Ageing. 2009;6(4):267. | ||

Brunborg B, Ytrehus S. Sense of well-being 10 years after stroke. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(7–8):1055–1063. | ||

Finne-Soveri H, Sorbye LW, Jonsson PV, Carpenter GI, Bernabei R. Increased work-load associated with faecal incontinence among home care patients in 11 European countries. Eur J Public Health. 2008;18(3):323–328. | ||

Schluter PJ, Ward C, Arnold EP, Scrase R, Jamieson HA. Urinary incontinence, but not fecal incontinence, is a risk factor for admission to aged residential care of older persons in New Zealand. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017;36(6):1588–1595. | ||

Johnston K, Grimmer-Somers K, Sutherland M. Perspectives on use of personal alarms by older fallers. Int J Gen Med. 2010;3:231–237. | ||

van den Berg N, Schumann M, Kraft K, Hoffmann W. Telemedicine and telecare for older patients- a systematic review. Maturitas. 2012;73(2):94–114. | ||

Hjelle KM, Alvsvag H, Forland O. The relatives’ voice: how do relatives experience participation in reablement? A qualitative study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2017;10:1–11. | ||

Ulmanen P, Szebehely M. From the state to the family or to the market? Consequences of reduced residential eldercare in Sweden. Int J Soc Welfare. 2015;24:81–92. | ||

Puts MT, Toubasi S, Andrew MK, et al. Interventions to prevent or reduce the level of frailty in community-dwelling older adults: a scoping review of the literature and international policies. Age Ageing. 2017;46(3):383–392. | ||

Bing-Jonsson PC, Hofoss D, Kirkevold M, Bjork IT, Foss C. Sufficient competence in community elderly care? Results from a competence measurement of nursing staff. BMC Nurs. 2016;15:5. | ||

Esbensen BA, Hvitved I, Andersen HE, Petersen CM. Growing older in the context of needing geriatric assessment: a qualitative study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2016;30(3):489–498. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.