Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 15

Sexual Harassment and Associated Factors Among Female Nurses: The Case of Addis Ababa Public Hospitals

Authors Weldesenbet H , Yibeltie J, Hagos T

Received 27 April 2022

Accepted for publication 11 October 2022

Published 18 October 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 3053—3068

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S372422

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Einar Thorsteinsson

Habtamu Weldesenbet,1 Jemberu Yibeltie,2 Tsega Hagos3

1Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Menelik II College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Kotebe University of Education, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2Department of Nutrition, Menelik II College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Kotebe University of Education, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 3Department of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Habtamu Weldesenbet, Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Menelik II College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Kotebe University of Education, P.O. Box 3268, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Email [email protected]

Background: Sexual harassment of female nurses at work is an issue that is receiving more attention globally and is progressively being acknowledged as a form of gender discrimination in the workplace. Africa’s situation is getting worse every day, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa. Determining the prevalence of workplace sexual harassment and associated factors among female nurses working in Addis Ababa public hospitals was the aim of this study.

Methods: A cross-sectional research design was conducted in August 2021 GC and 339 randomly selected female nurses working in an Addis Ababa public hospital were selected. The data were collected using a pre-tested, semi-structured questionnaire. EPI-Info 7 was used to enter the data, which was then exported to SPSS version 26 for further analysis.

Results: Forty six (46.6) percent of workplaces reported having experienced sexual harassment. One hundred sixty seven (49.3%) of all cases involved physical sexual harassment, while 79 (51.2%) involved verbal sexual harassment. Sexual harassment was 4.64 times more likely to happen to single female nurses than to married people (AOR= 4.64, 95% CI [2.6, 8.4]). Female nurses in the 20– 25 age group were roughly 4.7 times more likely to suffer sexual harassment than those in the > 40 age group (AOR=4.69, 95% CI [2.44, 9.03]). Alcohol consumers had a 4.5-fold higher chance of experiencing sexual harassment than non-consumers (AOR=4.50, 95% CI [2.40, 8.50]).

Conclusion: Violence among female nurses was demonstrated in this study. It demands a particular focus from the involved bodies. Age, marital status, and alcohol consumption were found to statistically significantly correlate with sexual harassment. Female nurses must get training that emphasizes behavior modification, and healthcare facilities must foster a pleasant atmosphere for nurses, patients, and other staff members.

Keywords: workplace, sexual harassment, female nurses, Addis Ababa, public hospitals, Ethiopia

Introduction

Any uncomfortable, offensive, or unwanted sexual activity that hinders an employee’s ability to perform their job is considered workplace sexual harassment. Any behavior intended to persuade someone to engage in sexual activity without their consent by the use of words, signs, or any other means “is considered to be sexual harassment. Sexual violence is defined as any sexual harassment that uses force, or any attempt to use force.” Employees who have experienced sexual harassment or physical abuse will be entitled to terminate their employment immediately and receive severance pay and other benefits.1

Sexual harassment is a multifaceted phenomenon that includes nonverbal, verbal and physical sexual violence/ abuse. The nonverbal sexual violence includes stalking, exhibitionism, showing sexual explicit pictures, or making sexual gestures; verbal sexual violence/ abuse – sexual comments, jeering or taunting and asking questions about sexual activity and physical sexual violence/ abuse which includes touching, kissing and more serious offenses such as rape.2,3 In many cases, both categories might be found in the same situation.4 Sexual harassment can take many forms, ranging from minor infractions to sexual abuse or violence. Harassment can occur in a variety of social settings, including the job, family, school, churches, and so on. Harassers and victims might be male or female.5

Sexual harassment frequently occurs in healthcare settings along with other forms of abuse, including verbal and physical assault, stalking, and bullying.6 Sexual harassment at work is an illegitimate use of power. It has nothing to do with appearance and is not attractive or complimentary. By disparaging, shaming, and refusing to hire, fire, or promote others, the offender abuses his or her position of powers.2,3 Sexual discrimination takes the form of workplace harassment. Examples include unwanted sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and sexual conduct that targets a person based on their gender.4

Examples of workplace violence and sexual harassment that take place on the job or as a result of a worker’s employment include sexual harassment, physical assault, murder, verbal abuse, bullying, and mobbing. Healthcare professionals are among those who are more likely to experience workplace violence (WPV). Four times as often as in any other private sector, violence happens in the healthcare sector. This is because healthcare professionals frequently interact with patients, clients, and their families at trying times. Patients or clients might behave aggressively.7

Workplace sexual harassment occurs when a woman is used as a sex object in the workplace. When a woman works in a position usually filled by men, harassment is more likely to happen because her gender is more obvious and she is perceived as a woman before a worker. It can also occur when a woman holds a position that has historically been held by women, in which case the workplace becomes more gendered and women are less likely to report harassment because it is seen as normal.8

Single nurses with more years of experience in nursing and higher education were more likely to be sexually harassed, and physicians and other nurses were two of the most common sources of sexual harassment.9,10 Sexual harassment is a widespread issue that prohibits women from integrating and remaining in the workforce.11

Everywhere in the globe, sexual harassment takes place. Among the occupations where it happens most frequently is nursing, but the incidence rates differ greatly depending on the region, the workplace, and the research methodology. Patient et al harassment is a problem for nurses.12 Men and women view sexual harassment differently, according to studies. The New York Times published the findings of a nationwide survey of workers in 12 firms who were asked about their experiences with sexual harassment in the previous year. According to the survey, 43% of women and 9% of men claimed to have experienced “sexual taunting” at work.

Only 1% of males and 98% of women reported receiving sexually explicit letters, phone calls, cartoons, or other materials.13 Nurses claim that sexual harassment creates a dangerous work atmosphere that lowers the standard of service. When a coworker is sexually harassing a patient, the nurse avoids necessary dialogue and does not ask them for help relocating the patient or providing care. Some nurses claim that sexual harassment makes it difficult for them to think effectively about assessments or patient care.14

China has a higher rate of workplace violence against nurses than other nations. Organized healthcare disruptions are just beginning to appear in China.15 Registered nurses in Japan were much more likely to experience sexual harassment than nurse assistants. Additionally, registered nurses showed a significantly more favorable attitude toward gender equality when compared to assistant nurses.16 In Italy, 43% of nurses and 34% of nursing students reported experiencing at least one upsetting incident of physical or verbal abuse throughout their careers working in clinical settings.17

A study found a high prevalence of WPV in a Kenyan tertiary hospital’s emergency department. Work place violence had been experienced by more than three-quarters of the participants, with verbal abuse, physical violence, and sexual harassment being the most common. Patients or their family were the main offenders of WPV.18

Sexual harassment in the workplace is common in Ethiopia. Workplace violence was two times more common among female nurses than it was among male nurses. Those without a spouse are also twice as likely to be victims of workplace violence as those who do. Those who drank alcohol were more likely to experience workplace violence than those who did not. Furthermore, smokers are three times more likely than non-smokers to encounter workplace violence.7

Many researches about sexual harassment in general have been done in Ethiopia. However, there is little information available regarding sexual harassment of female nurses at work. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of workplace sexual harassment and its contributing factors among female nurses working in Addis Ababa’s public hospitals. The policy makers will utilize the study’s research findings as a starting point for developing measures to combat workplace sexual harassment of female nurses.

Conceptual Framework

According to the above literature review, there are many factors which expose female nurses to sexual harassment in work place, among these factors the some of them are socio demographic factors, substance related factors, environmental factors. The following diagram illustrates the cause of sexual harassment against female nurses (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1 Flowchart shows conceptual framework of the study. Adapted with permission Dove Medical Press. Weldehawaryat HN, Weldehawariat FG, Negash FG. Prevalence of workplace violence and associated factors against nurses working in public health facilities in southern Ethiopia. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2020;13:1869.6 |

Methods and Materials

Study Design and Area

In Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, a community-based cross-sectional study was done. The study was conducted on female nurses who were working in Addis Ababa public hospitals. The data were collected in August 2021 GC. Addis Ababa (Amharic: አዲስ አበባ, “new flower”), also known as Finfinne is the capital and largest city of Ethiopia.19

Addis Ababa’s present metro area population is 5,228,000 in 2022, up 4.43% from 2021.20 It is the seat of the African Union, as well as its predecessor, the Organization of African Unity (OAU). It also serves as the headquarters for the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (ECA), as well as a number of other regional and international organizations. As a result of its historical, diplomatic, and political significance for the continent, Addis Ababa is often referred to as “Africa’s political clout”.21

The city is surrounded by the Oromia Special Zone and is populated by people from all around Ethiopia. St. Paul’s Hospital, Millennium Medical College, Menelik II Hospital, Eka Kotebe Hospital, and Trunesh Beijing Hospital all participated in the research.

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion Criteria

Female nurses who were actively working in the randomly selected public hospitals in Addis Ababa were included in the study.

Exclusion Criteria

All female nurses with less than 6 months of experience at the time of data collection were excluded from the study because they lacked sufficient familiarity with the study’s outcome variables. In addition, those individuals in sick leave, annual leave and on retirement were excluded from the study.

Sample Size Determination and Sampling Technique

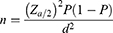

The sample size was calculated using a single proportion formula with 29.9% from the previous study,22 with 5% margin of error 95% confidence interval, and a Z value 1.96, and a 10% non-response rate.

Based on the assumption, a total sample size was calculated using the formula indicated above. Where:

- n = sample size

- p = estimated proportion

- d = allowed error

- Z = the score associated with selected degree of confidence interval at 95% confidence interval was 1.96 and adding 10% to compensate for non-response and non-complete questions.

n = 323

Contingency = 323X10/100

= 32.3

The total sample size was 356.

Using simple random sampling, four public hospitals under the control of both the Addis Ababa health bureau and the federal health office were chosen from a total of 13 public hospitals. The sample size was then proportionally allocated to each of the selected public hospitals and the nurses were selected using systematic random sampling from a list of nurses working in each of the public hospitals that were chosen (Figure 2).

|

Figure 2 Sampling frame-subjects drawn in proportion to female population in each faculty. |

Data Collection Tools and Procedures

A semi-structured questionnaire was used to collect the data. The questionnaire was written in English and translated back to local language (Amharic). The questionnaire provided an opportunity to examine possible determinants of sexual harassment and its incidence as well as to measure socio-demographic and socio-economic aspects. Previous similar studies and internationally acknowledged questionnaire guidelines were used to build the questionnaire.7,18–24

Two data collectors were assigned in each of the selected hospitals to collect the sample. Data collectors received one-day training about how to communicate with participants, how to use the questionnaire, and how to collect the data. Males and females both took part in the data collection process.

Covid-19 Prevention Methods During Data Collection

Data collectors were urged to follow national legislation, guidelines, and practices while collecting data. Because the novel coronavirus can survive on paper for up to three days, any paper-based research is at risk of infection. Participants and data collectors are not allowed to exchange paper during data collection with the nurses without glove. The data collectors advised the nurses to use masks during data collection. Precautions involving Covid-19 were implemented during the data collection process. Nurses who did not have personal protective equipment were given it, and instruments were disinfected before and after data collection according to the COVID-19 protocol.

Operational Definition

Workplace Sexual Harassment

Inappropriate sexual statements, gestures, or physical advances were all part of the behavior. When the study participants were subjected to at least one kind of violence, such as physical sexual harassment, verbal sexual harassment, or nonverbal sexual harassment, in the context of their employment or personal lives.25 Twenty five questions had been used to assess the prevalence of workplace sexual harassment of female nurses. In this study the likert scale, not all was considered as no sexual harassment while little, somehow and few were considered as yes for sexual harassment.

Physical Sexual Harassment

Sexual assault or sexual rape, inappropriately touching or grabbing someone’s breast or any body parts, Kissing or hugging someone inappropriately at work place at least once in their lives.26

Verbal Sexual Harassment

Any sexually related questions, comments, jokes, abusive languages which made study participants less comfortable at their workplace at least once during their life time.25

Nonverbal Sexual Violence

Includes stalking, exhibitionism, showing sexual explicit pictures, or making sexual gestures at their workplace at least once during their life time.25

Drinking Alcohol

Those who drink alcohol at any place at least once a week or occasionally in their day today activities.

Chewing Khat

Those who chew khat at any place at least once a week. Chewing Khat is mastication of the leaf of the khat with sugar for prolonged period without swallowing the roughage. It is a stimulant and many people living in lowland and young people in cities of some countries like Ethiopia they chew Khat.

Working Department

Division of working areas in hospital, in which daily activities will be done and which has its own team and team coordinator.

Work Schedule

Specific days or nights, on which nurses do their work at least for 8 hours.

Data Quality Management

The quality of the data was ensured by creating a standardized questionnaire, providing proper training and orientation for the data collectors, and closely monitoring the data gathering process during the actual collection period. The questionnaire was prepared in English version and translated to Amharic and back to English to confirm the consistency of the questionnaire. The questionnaire was pre-tested to identify potential problem areas, unanticipated interpretations and cultural objections to any of questions of sexual harassment in Addis Ababa by taking 5% of the sample size on 30 female nurses who were not part of the study at AaBET Hospital. Based on the pretest results, the questionnaire additionally adjusted contextually and terminologically, accordingly some changes were made to the questionnaire. Regular supervision was made by supervisors and the investigator and counter checking was made for daily filled questionnaires.

All the data collectors and supervisors were trained by the principal investigator for one day on the study objectives, purpose and interviewing techniques based on the research instrument. During the data collection period daily briefing held to ensure the targeted objective for the day. Collected data were entered to with Epi Info 7 for cleaning then further export into with SPSS version 26.0 for further analysis.

Data Processing and Analysis

The data was reviewed for completeness and consistency before being coded, entered, and cleaned with Epi Info 7 data program, and then analyzed with SPSS version 26.0. To show the distribution of each variable, descriptive statistics such as frequency distribution and mean were used. With a 5% threshold of significance, binary logistic regression was used to examine the strength of the outcome variable’s association with the fitted independent factors.

Age, marital status and alcohol consumption were all statistically significant independent variables when compared to the dependent variable. Educational level, work experience, working departments, working schedule, and substance/drug use were all independent variables that were not statistically significant when compared to the dependent variable. Omnibus and Hosmer-Lemeshow tests were performed at a 5% significant level. The Omnibus test was significant, as evidenced by the p – value <0.001, degree of freedom18 and chi – square values (134.63). With a p – value of 0.238, a degree of freedom of,9 and a chi – square value of 0, the Hosmer-Lemeshow test was insignificant (10.40). As a result, the models were appropriate for the research.

In block = 0, the percentage classification table was (53.4%), whereas in block =1, it was (53.4%). (74%). As a result, in this test, the classification was accurate. Because the constant variable’s significance was p<0.001, this model can include more variables.

Result

Socio-Demographic Characteristics

The final study contained 339 respondents, resulting in a response rate of 95.2%. Two hundred two (59.6%) of the respondents were from St’ Paul hospital, 55 (16.2%) from Menelik II hospital, 54 (15.9%) from Tirunesh Beijing hospital, and 28 (8.3%) from Eka Kotebe hospital. The participants’ mean age was 28 years (SD=4.90), and 174 (51.3%) of them were married. In terms of education, over two-thirds of them (256/75.5%) held a bachelor’s degree in nursing. The average monthly wage of the 148 (43.7%) responders was between 6000 and 8000 Ethiopian birr (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Nurses Working at Public Health Facilities in Addis Ababa Ethiopia, August, 2021 (n=339) |

Organizational and Workplace Characteristics

Almost all of the 324 study participants (95.6%) were full-time employees. Approximately 62 (18.3%) of the individuals worked in the Gynaecology/Obstetrics department, with 11 (3.2%) working in the Recovery department. Approximately 265 (78.2%) of the participants said they worked day and night shifts. Nearly half of the 162 participants in the study (47.8%) had less than or equal to 5 years of experience. Half of them (48.4%) said that upper hospital management’ responses to sexual harassment were positive. The sex of their immediate supervisors was revealed by a large number of 134 (39.5%) survey participants (See Table 2).

|

Table 2 Organizational and Workplace Characteristics of Nurses Working at Public Hospitals in Addis Ababa Ethiopia, August, 2021 (n=339) |

Prevalence of Sexual Harassment

Overall, 158 (46.6%) of those polled said they had been subjected to sexual harassment at some point in their lives. The majority of the respondents (162) (47.8%) had no knowledge of workplace sexual harassment, whereas only 21(6.2%) had limited knowledge of harassment.

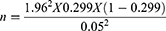

The majority of sexual harassments were committed by employees 51(32.3%), followed by external colleagues/other workers 33(20.9%), and the majority of harassers 55(34.8%) were alcoholics. Seventy eight (78) (49.4%) of the total respondents had experienced physical sexual harassment at some point in their lives. Among the total respondents, 79 (51.2%) had experienced verbal sexual harassment (talking in sexual terms) at some point in their lives. Nearly half of all nurses (48.7%) have had at least one incidence of sexual harassment throughout their careers. One hundred seventy 170(50.1%) of the total sexual harassments conducted against nurses occurred at night, and 32 (20.3%) of the total sexual harassment committed against nurses was reported to the appropriate authorities (See Table 3). One third, 49(31.0%) of sexual harassment happened in nursing room. The least 2 (1.3%) sexual harassment happened in doctors’ room (Figure 3).

|

Table 3 Prevalence of Sexual Harassment Against Female Nurses in Addis Ababa Public Hospital August, 2021 (n=339) |

|

Figure 3 Place of sexual harassment. |

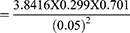

One third 47 (29.7%) of forms sexual harassment is “unnecessary touch or unwelcome sexual contact” whereas, making intercourse offer 23 (14.6%) and making sexual comments 23 (14.6%) are in the same amount (Figure 4).

|

Figure 4 Forms of sexual harassment. |

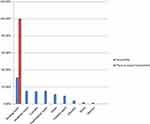

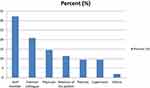

One third 21 (32.8%) of female nurses sexually harassed by their staff members, this indicates that, the leading perpetrators in Addis Ababa public hospitals are staff members. The second 14 (20.9%) perpetrators are external colleagues (Figure 5).

|

Figure 5 Identity of sexual harasser. |

Factors Associated with Workplace Sexual Harassment Against Female Nurses

With a 5% level of significance, binary logistic regression was used to assess the strength of the outcome variable’s association with the fitted independent variables. Age, marital status, and alcohol use were the three independent factors in this test that were statistically significant with the dependent variable. Omnibus and Hosmer-Lemeshow tests were performed at a 5% significant level. The Omnibus test was significant, with a p – value <0.001, a degree of freedom of,8 and a chi – square value of (135.46). With a p – value of 0.163, a degree of freedom of,8 and a chi – square value of 0, the Hosmer-Lemeshow test was insignificant (10.48). As a result, the models were appropriate for the research.

In block = 0, the percentage classification table was (53.4%), whereas in block =1, it was (74.3%). As a result, in this test, the classification was accurate. Because the constant variable’s significance was p<0.001. This model can include more variables. The multivariable logistic regression analysis included the respondent’s age, marital status, alcohol consumption, and chewing khat. In a multivariate analysis, the respondent’s age, marital status, and alcohol consumption were all revealed to be statistically significant predictors.

Single people were 4.64 times more likely than married people to experience sexual harassment (AOR=4.64, 95% CI [2.57, 8.39]). Nurses in the 20–25 age group were nearly 4.7 times and those nurses with age group 26–30 were 5.14 times more likely than those in the >40 age group to experience sexual harassment (AOR=4.69, 95% CI [2.44, 9.03]) and (AOR=5.14, 95% CI [2.45, 10.73]) respectively. Those who consume alcohol had a 4.5-fold higher risk of sexual harassment than those who do not (AOR=4.50; 95% CI [2.40, 8.45]) (Table 4).

|

Table 4 Binary Logistic Regression Analysis of Workplace Sexual Harassment Against Female Nurses Working at Public Health Hospitals in Addis Ababa Ethiopia, August, 2021 (n=339) |

Discussion

The prevalence of sexual harassment and its related factors were investigated in this study, and the life-time prevalence rate of sexual harassment against female nurses in Addis Ababa public hospitals was 46.6%. This finding was in line with research undertaken in Slovenia (42.0%), Italy (43%), and Ethiopia (43.1%). However, when compared to studies conducted in Greece (67%) and North-eastern China (83.3%), Japan (55.8%), Palestine (80.4%), Korea (95.5%), Indonesia (54.6%), Gambia (62.1%), and Gondar, Ethiopia, the figure is lower (58.2%).

This could be related to socio-cultural disparities and healthcare system differences. It could also be attributed to a lack of transparency and under-reporting of violent events due to a fear of expressing the truth. When compared to a study conducted in Hawassa, Southern Ethiopia, the magnitude of sexual harassment was higher (29.9%). This could be attributed to differences in health facility setup, as well as urbanization and the presence of more cultural and department diversity in Addis Ababa than in Hawassa. This could possibly be attributable to time disparities, since individuals in recent times have been subjected to various political and socioeconomic instability, which could have acted as a catalyst for violence against nurses.27–30

There was a statistically significant relationship between age and workplace violence in this study, indicating that as the age of health professionals’ increases, the violence perpetrated against them will decrease. When compared to their older counterparts, young nurses were more likely to experience workplace violence. This finding is consistent with findings from research in Japan, Malaysia, Turkey, and Taiwan. This could be due to a lack of expertise or experience coping with aggression among young nurses, as well as insufficient safety precautions. Furthermore, this could be explained in part by the fact that older individuals, particularly health care practitioners, are treated with respect in Ethiopian culture and possibly elsewhere. Other factors could include the fact that the younger nurses’ appearance and beauty are more appealing than the older ones.31–34

Unnecessary touch or uninvited contact was shown to be the most common type of workplace violence in this study, which is similar with other studies conducted in different nations. Nigeria (79.3% of the total) Southern Ethiopia’s Gedeo zone This could be due to the fact that nurses are very near to their patients, and most hospital working places are closed most of the time for the patient’s privacy, making it easy for offenders to perpetrate.35,36

Sexual harassment towards nurses was also found to have a statistically significant relationship with marital status. This conclusion was supported by research undertaken in Japan, Egypt, and northwest Ethiopia. According to this study, nurses who lived alone were three times more likely than those who lived with their spouse to be subjected to sexual harassment. This could be because the majority of nurses without a spouse are under the age of 30, which has been shown to be a predictor of sexual harassment in many studies. It’s also possible that the perpetrators consider harassing married people is more difficult than bothering single people.31,36,37

Nurses who use alcohol are more likely to experience sexual harassment than those who do not. This research is in line with that conducted in southern Ethiopia’s Gamogofa and Gedeo zones. This may occur because such types of alcohol may cause people to perform their tasks in a haphazard manner, allowing others to attempt to perpetrate violence against them. Or it could be that in most small towns, the personal lives of nurses are not disguised, and people who drink alcohol are culturally devalued by the perpetrators. Furthermore, female nurses do not drink alone; instead, they drink with male acquaintances, exposing them to various forms of aggression from their peers.7,36

This study found that the majority of nurses are harassed by their coworkers, which is similar to research undertaken in Hong Kong and Malaysia. This could be because daily contact increases the chances of knowing what someone looks like and understanding his negative side. This could lead to colleagues abusing one another. In other words, as colleagues become more intimate with one another, they may not recognize the boundaries that exist between them, and touching their colleagues sexually may appear natural to them.26,38

Recommendation

The magnitude of work area sexual harassment is high in Addis Ababa public health hospitals. Therefore, more focus should be given to the public hospitals in Addis Ababa to prevent women’s work area sexual harassment. Similarly staff employees should be given health education about women’s work area sexual harassment. In general, women’s empowerment and awareness creation in the society is important to protect women’s from sexual harassment.

Limitation of the Study

Although a representative random sampling was employed, the study was limited to four public hospitals and did not include private or other public health sectors in Addis Ababa due to time and budget constraints. Furthermore, the data was collected using a retrospective self-reporting method. This strategy relies on the participants’ capacity to recollect events that occurred prior to the study, which could lead to biases. Another potential weakness of this study was the study participants’ unwillingness to give personal information. Comparisons were challenging due to a lack of study in the Ethiopian environment. Culturally females perceive that sexual harassment is normal. There is also fear of social stigma when they are exposing themselves for their being sexually harassed.

Conclusion

The magnitude of sexual harassment towards female nurses in Addis Ababa public hospitals was found to be 46.6% in this study. According to the findings, violence was a significant work danger and a public health concern. The studies also demonstrated that the features of different types of violence had different characteristics. The most common kind of sexual harassment was unwanted touch or contact, but other forms were often recorded, and staff employees were the most common perpetrators of female sexual harassment. In addition, statistically significant factors that influence workplace sexual harassment against nurses include age, marital status, and alcohol consumption.

Abbreviations

ETB, Ethiopian Birr; FMHACA, Food Medicine Health Administration Control Office; WHO, World Health Organization; RTE, ready-to-eat; FBD, food borne disease; SVF, street food vendor.

Data Sharing Statement

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author without limitation.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The Institutional Review Board at Kotebe Metropolitan University and Menelik II Health Science College, Addis Ababa health bureau public health research and emergency management, St’ Paul millennium medical college, and Eka Kotebe hospital all gave their approval before the data was collected. Each relevant body was required to send a written letter of cooperation to the respective public health facilities. Participation in the study was based on informed consent, and the confidentiality of the data was ensured by removing names from the list of study participants. Participants were told that if they did not feel comfortable, they could refuse or withdraw from the study at any moment. The study adhered to all ethical guidelines established by the National Research Ethics Review Committee (NRERC). This research study also complies with the declaration of Helsinki.

Acknowledgment

First, I would like to express my gratitude to the Department of Health Service Management at Kotebe University of Education-Menelik II Medical and Health Sciences College for providing me with the opportunity to complete this thesis. I want to express my gratitude to the research and administrative staff at the hospitals of St. Paul, Menelik II, Tirunesh Beijing, and Eka Kotebe. And I’d want to express my gratitude to the female nurses who work in the aforementioned hospitals for their assistance in completing the questionnaire. I’d like to thank everyone who helped me to collect the data (Sr. Megdelawit-Mola, Sr. Nardos-Tilahun, Sr. Mestawot-Kebede, Sr. Hibstemena-Anbese, Misganaw-Lijalem, Shimels-Yeshiwas, and Chalkulh-Sewnet). Finally, I’d like to express my gratitude to Mr Meseret-Yibeltie, my younger and sweeter brother, for his unwavering support throughout the thesis.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

1. McSherry B, Brass JN, Leonard DK. The political economy of pro-poor livestock policy reform in Kenya. IGAD LPI Working Paper 04–08; 2008.

2. Hamlin L, Hoffman A. Perioperative nurses and sexual harassment. AORN J. 2002;76(5):855–860. doi:10.1016/S0001-2092(06)61039-9

3. Ceccato V, Loukaitou-Sideris A. Fear of sexual harassment and its impact on safety perceptions in transit environments: a global perspective. Violence Against Women. 2022;28(1):26–48. doi:10.1177/1077801221992874

4. Díaz-Andreu M, Lucy S, Babic S, Edwards DN. Archaeology of Identity. Taylor & Francis; 2005.

5. Nelson R. Sexual harassment in nursing: a long-standing, but rarely studied problem. AJN Am J Nurs. 2018;118(5):19–20. doi:10.1097/01.NAJ.0000532826.47647.42

6. Weldehawaryat HN, Weldehawariat FG, Negash FG. Prevalence of workplace violence and associated factors against nurses working in public health facilities in southern Ethiopia. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2020;13:1869. doi:10.2147/RMHP.S264178

7. Samuels H, editor. Sexual Harassment in the Workplace: A Feminist Analysis of Recent Developments in the UK. Women’s Studies International Forum. Elsevier; 2003.

8. Celik Y, Çelik SŞ. Sexual harassment against nurses in Turkey. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2007;39(2):200–206. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00168.x

9. Duldt BW. Sexual harassment in nursing. Nurs Outlook. 1982;30(6):336–343.

10. Newman C, Nayebare A, Neema S, Agaba A, Akello LP. Uganda’s response to sexual harassment in the public health sector: from “Dying Silently” to gender-transformational HRH policy. Hum Resour Health. 2021;19(1):1–19. doi:10.1186/s12960-021-00569-0

11. Jenner SC, Djermester P, Oertelt-Prigione S. Prevention strategies for sexual harassment in academic medicine: a qualitative study. J Interpers Violence. 2022;37(5–6):NP2490–NP515. doi:10.1177/0886260520903130

12. Arnetz BB, Ekman R. Stress in Health and Disease. Wiley-VCH; 2006.

13. Kahsay WG, Negarandeh R, Dehghan Nayeri N, Hasanpour M. Sexual harassment against female nurses: a systematic review. BMC Nurs. 2020;19(1):1–12. doi:10.1186/s12912-019-0393-4

14. Adams EA, Darj E, Wijewardene K, Infanti JJ. Perceptions on the sexual harassment of female nurses in a state hospital in Sri Lanka: a qualitative study. Glob Health Action. 2019;12(1):1560587. doi:10.1080/16549716.2018.1560587

15. Howard LG. The Sexual Harassment Handbook: Protect Yourself and Coworkers from the Realities of Sexual Harassment, Take Action, Investigate, and Remedy Accusations of Harassment, Create Corporate Policies That Educate and Empower Employees. Career Press; 2007.

16. Valente SM, Bullough V. Sexual harassment of nurses in the workplace. J Nurs Care Qual. 2004;19(3):234–241. doi:10.1097/00001786-200407000-00010

17. Frank E, Brogan D, Schiffman M. Prevalence and correlates of harassment among US women physicians. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(4):352–358. doi:10.1001/archinte.158.4.352

18. Papantoniou P. Comparative analysis of sexual harassment between male and female nurses: a cross‐sectional study in Greece. J Nurs Manag. 2021. doi:10.1111/jonm.13419

19. Lu L, Dong M, Lok GK, et al. Worldwide prevalence of sexual harassment towards nurses: a comprehensive meta‐analysis of observational studies. J Adv Nurs. 2020;76(4):980–990. doi:10.1111/jan.14296

20. Cavalcanti AL, Eduardo Dos Reis B, de Castro Marcolino E, et al. Occupational violence against Brazilian nurses. Iran J Public Health. 2018;47(11):1636.

21. Worke MD, Koricha ZB, Debelew GT. Prevalence of sexual violence in Ethiopian workplaces: systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Health. 2020;17(1):1–15. doi:10.1186/s12978-020-01050-2

22. Williams MF. Violence and sexual harassment: impact on registered nurses in the workplace. AAOHN J. 1996;44(2):73–77. doi:10.1177/216507999604400204

23. Committee W, Douglas PS, Mack MJ, et al. 2022 ACC health policy statement on building respect, civility, and inclusion in the cardiovascular workplace: a report of the American college of cardiology solution set oversight committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(21):2153–2184.

24. Magnavita N, Heponiemi T. Workplace violence against nursing students and nurses: an Italian experience. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2011;43(2):203–210. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2011.01392.x

25. Hibino Y, Hitomi Y, Kambayashi Y, Nakamura H. Exploring factors associated with the incidence of sexual harassment of hospital nurses by patients. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2009;41(2):124–131. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2009.01244.x

26. Kisa A, Dziegielewski SF, Ates M. Sexual harassment and its consequences: a study within Turkish hospitals. J Health Soc Policy. 2002;15(1):77–94. doi:10.1300/J045v15n01_05

27. Bronner G, Peretz C, Ehrenfeld M. Sexual harassment of nurses and nursing students. J Adv Nurs. 2003;42(6):637–644. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02667.x

28. Zhang L, Wang A, Xie X, et al. Workplace violence against nurses: a cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2017;72:8–14. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.04.002

29. Celik SS, Bayraktar N. A study of nursing student abuse in Turkey. J Nurs Educ. 2004;43(7):330–336. doi:10.3928/01484834-20040701-02

30. Douglas K, Enikanoselu O. Workplace violence among nurses in general hospitals in Osun State, Nigeria. Niger J Med. 2019;28(4):510–521. doi:10.4103/1115-2613.278642

31. Ali EAA, Saied SM, Elsabagh HM, Zayed HA. Sexual harassment against nursing staff in Tanta University Hospitals, Egypt. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2015;90(3):94–100. doi:10.1097/01.EPX.0000470563.41655.71

32. Kibunja BK, Musembi HM, Kimani RW, Gatimu SM. Prevalence and effect of workplace violence against emergency nurses at a tertiary hospital in Kenya: a cross-sectional study. Saf Health Work. 2021;12(2):249–254. doi:10.1016/j.shaw.2021.01.005

33. Yenealem DG, Woldegebriel MK, Olana AT, Mekonnen TH. Violence at work: determinants & prevalence among health care workers, northwest Ethiopia: an institutional based cross sectional study. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2019;31(1):1–7. doi:10.1186/s40557-019-0288-6

34. Sisawo EJ, Ouédraogo SYYA, Huang S-L. Workplace violence against nurses in the Gambia: mixed methods design. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):1–11. doi:10.1186/s12913-017-2258-4

35. Tollstern Landin T, Melin T, Mark Kimaka V, et al. Sexual harassment in clinical practice—a cross-sectional study among nurses and nursing students in sub-Saharan Africa. SAGE Open Nurs. 2020;6:2377960820963764. doi:10.1177/2377960820963764

36. Wei C-Y, Chiou S-T, Chien L-Y, Huang N. Workplace violence against nurses–prevalence and association with hospital organizational characteristics and health-promotion efforts: cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;56:63–70. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.12.012

37. Fute M, Mengesha ZB, Wakgari N, Tessema GA. High prevalence of workplace violence among nurses working at public health facilities in Southern Ethiopia. BMC Nurs. 2015;14(1):1–5. doi:10.1186/s12912-015-0062-1

38. Robbins I, Bender MP, Finnis SJ. Sexual harassment in nursing. J Adv Nurs. 1997;25(1):163–169. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997025163.x

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.