Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

Self-Esteem and Self-Compassion: A Narrative Review and Meta-Analysis on Their Links to Psychological Problems and Well-Being

Received 8 June 2023

Accepted for publication 30 July 2023

Published 3 August 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 2961—2975

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S402455

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Peter Muris,1,2 Henry Otgaar1,3

1Department of Clinical Psychological Science, Faculty of Psychology and Neuroscience, Maastricht University, Maastricht, the Netherlands; 2Department of Psychology, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa; 3Institute of Criminology, Faculty of Law and Criminology, Catholic University of Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

Correspondence: Peter Muris, Department of Clinical Psychological Science, Faculty of Psychology and Neuroscience, Maastricht University, P.O. Box 616, Maastricht, 6200 MD, the Netherlands, Email [email protected]

Abstract: The present review addressed the relationship between two self-related concepts that are assumed to play a role in human resilience and well-being: self-esteem and self-compassion. Besides a theoretical exploration of both concepts, a meta-analysis (k = 76, N = 35,537 participants) was conducted to examine the magnitude of the relation between self-esteem and self-compassion and their links to indices of well-being and psychological problems. The average correlation between self-esteem and self-compassion was strong (r = 0.65, effect size = 0.71), suggesting that – despite some distinct features – the overlap between both self-related constructs is considerable. Self-esteem and self-compassion displayed relations of a similar magnitude to measures of well-being and psychological problems, and both concepts accounted for unique variance in these measures once controlling for their shared variance. Self-esteem and self-compassion can best be seen as complementary concepts and we invite researchers to look more at their joint protective role within a context of well-being and mental health as well as to their additive value in the treatment of people with psychological problems.

Keywords: self-esteem, self-compassion, resilience, well-being, psychological problems, interventions

Introduction

William James already described “selfhood” as an essential concept of human psychology. He divided the self into two parts: the “Me”, which refers to people’s reflections about themselves (ie, subjective perceptions of personal characteristics, eg, defining oneself as “rich”, “introvert”, or “intelligent”), and the “I”, which refers to the thinking self that knows who one is or what he/she has been doing in the current and past (also known as the mind).1 Ever since, many scholars attempted to conceptualize the self,2 varying from rather concrete descriptions, such as “a collection of abilities, temperament, goals, values, preferences that distinguish one individual from another”3 to more abstract conceptualizations involving the dynamic self-constructive process of one’s identity as a result of reflexive activities involving thinking, being aware of thinking, and taking the self as an object of thinking.4 Many self-related constructs, processes, and phenomena have been described in the psychological literature,5 but within the field of mental health and psychopathology, two concepts have received a considerable amount of empirical attention: self-esteem and self-compassion.

Self-esteem and self-compassion reflect an affectively and/or cognitively charged attitude or response to the self. The nature of both constructs is fundamentally positive, meaning that persons with high levels of self-esteem and self-compassion ought to display greater resilience and higher levels of well-being, and hence lower levels of all kinds of mental health problems. Despite their conceptual overlap, there exist a number of differences between self-esteem and self-compassion.6 The present review article is focused on the relationship between self-esteem and self-compassion. We will first describe both concepts independently from a more theoretical perspective and address their protective role within the context of mental health and psychopathology. Next, we will focus on the link between self-esteem and self-compassion thereby addressing similarities as well as dissimilarities. The review is not only qualitative in nature, but also includes a meta-analysis to assess the strength of the relation between self-esteem and self-compassion as well as to examine the (unique) links between both self-related concepts on the one hand and indices of well-being and psychopathology on the other hand. Furthermore, we will discuss to what extent self-esteem and self-compassion are susceptible to change and hence might be a suitable target for psychological interventions. Finally, we will provide a brief summary of our findings and address the role and importance of both self-related constructs for understanding human resilience and well-being.

Self-Esteem

Self-esteem refers to an affectively laden evaluation of the self.7 More specifically, this construct refers to “an individual’s subjective evaluation of his or her worth as a person”.8 This is defined by a person’s perception of his/her abilities and qualities in various domains, including intellect, work performance, social skills, physical appearance, and athletics. It is important to emphasize that self-esteem does not necessarily reflect the actual abilities or features of a person but mainly refers to how a person thinks or feels about these qualities and characteristics. There is concrete evidence that the concept reflects a trait-like variable that is relatively stable across time. For example, Kuster and Orth9 conducted a longitudinal study with repeated measurements taken from adolescence to old age and showed that

self-esteem does not fluctuate continuously over time in response to the inevitable mix of successes and failures we all experience as we go through life [but has] a level of stability that is comparable to that of basic personality characteristics such as neuroticism and extraversion.

Their data indicated that one can foretell a person’s relative level of self-esteem (as compared to other people, eg, high versus low) across decades of life.8

Regarding the function of self-esteem, three main perspectives have been proposed. First, the self-determination perspective assumes that self-esteem serves a motivational function that prompts people to take care of themselves and to explore and reach their full potential.10 A distinction is made between contingent self-esteem, which refers to positive feelings and thoughts about oneself that are dependent on some achievement or fulfilment of expectations, and true self-esteem, which pertains to a stable, securely based, and solid sense of the self. Or in other words: The person is comfortable with whom he/she is and how others will perceive him/her and is no longer involved in a process of critical self-evaluation. Both types of self-esteem are related to human motivation. Contingent self-esteem is predominantly linked with extrinsic motivation: A good sense of the self is achieved because one engages in activities that will yield a reward or avoid punishment, whereas true self-esteem is typically associated with intrinsic motivation: Positive feelings of self-worth are elicited when performing activities that match one’s personal needs and values.

The second perspective on the function of self-esteem is subsumed under the terror management theory.11 According to this perspective, human beings can be distinguished from other species because they can reflect on the fact that the world in which they live is an uncontrollable, absurd setting in which their own impeding death is the only inevitable certainty. To cope with this mortality salience, people have developed a cultural worldview that is infused by order, predictability, meaning, and continuity. Terror management theory postulates that self-esteem refers to a sense of personal value that is grounded in beliefs about the validity of the worldview and the extent to which one can abide to the cultural standards of that worldview, which would function as a buffer against the fear of death.12 People with high self-esteem have a more positive and less fatalistic attitude towards life than people with low self-esteem, and hence are better able to deal with everyday reminders of their death and the finiteness of life.

The third account is the sociometer perspective that views self-esteem as an innate monitoring system that measures a person’s relational value to other people, or in more concrete words: “the degree to which other people regard their relationship with the individual to be valuable, important, or close”.13 When self-esteem is high, the person has the idea that he/she is valued by others as a respectable and worthy individual and this will fuel behaviours that serve to maintain and enhance relationships with other people in order to preserve this social status. In contrast, when self-esteem is low, the person perceives that his/her social position is on the line, which evokes an emotional response as an alarm signal that prompts behaviours to gain and restore relations with others. Thus, according to sociometer perspective, self-esteem is viewed as an affect-driven meter that continuously monitors and reacts to signs of social acceptance and rejection. This monitoring system would have evolutionary roots because relationships with other people are an important asset promoting survival.14

Self-Esteem and Life Outcomes

Whether conceiving self-esteem as a vehicle of motivation, a buffer against the fear of death, or a social thermometer, all these functional accounts align with the notion that the construct has a positive nature and hence may promote psychological well-being and protect against mental health problems. Although some scholars are rather critical and sceptic about the presumed benefits of self-esteem, arguing that its merits are quite limited and that there are even downsides of having (too) much confidence in one’s worth,15 there is a voluminous amount of empirical work supporting its association with positive outcomes. For instance, in an influential large-scale study including more than 13,000 college students in 31 countries from all over the world, self-esteem correlated positively with life satisfaction (with an average r of 0.44),16 meaning that the more participants were content with themselves, the stronger they indicated being happy with their life. As another example, Chen et al17 conducted a meta-analysis to examine the relationship between self-esteem and depression. Using the data of 50 cross-sectional studies conducted in Taiwan, a mean correlation of −0.48 was detected, indicating that higher levels of self-esteem were associated with lower levels of this type of emotional psychopathology. In a recent comprehensive meta-analytic review of the literature, Orth and Robbins18 drew up the balance and concluded that

high self-esteem helps individuals adapt to and succeed in a variety of life domains, including having more satisfying relationships, performing better at school and work, enjoying improved mental and physical health, and refraining from antisocial behaviour.

Self-Compassion

Self-compassion refers to how people treat themselves when they encounter failure, deficiencies, or suffering in their personal life. According to the widely used definition of Neff,19 the construct consists of three key elements: (1) self-kindness, which refers to being warm, kind, and understanding towards oneself in times of adversity; (2) common humanity, which pertains to the acknowledgment that all human beings face challenges in life and hence are subject to drawbacks and suffering; and (3) mindfulness, which has to do with an awareness of personal discomfort while maintaining the perspective on other more positive aspects in life. In general, self-compassion entails displaying a positive and healthy attitude to the self, which enables the individual to deal effectively with the usual setbacks in human existence.20

About the functionality of self-compassion, Gilbert21 conceptualized the construct in evolutionary terms. This scholar initially focused on compassion, which he viewed as a motivational system to regulate the negative affect of other people through engagement in supportive and affiliative actions that ultimately serve to maintain the group bonding and as such the survival of the species. Because human beings gradually developed the mental capacity to reflect on themselves, they can also deploy compassion towards the self in case they encounter setbacks and associated negative emotions. This self-compassion enables them to effectively cope with such emotional dysregulation ensuring their full participation in social life.

In a recent review of the literature, Strauss et al22 concluded that

[self-]compassion is a complex construct that includes emotion but is more than an emotion, as it includes perceptiveness or sensitivity to suffering, understanding of its universality, acceptance, non-judgment, and distress tolerance, and intentions to act in helpful ways.

In view of these elements, one might expect that self-compassion tends to fluctuate over time and across situations, but there are clear indications that the construct – just like self-esteem – is quite stable and thus can best be seen as a trait-like individual difference variable.23

Self-Compassion and Life Outcomes

Since its introduction in the psychological literature, many studies have been conducted investigating the positive effects of self-compassion. For example, Zessin et al24 conducted a meta-analysis examining the relationship between self-compassion and various types of well-being, such as happiness, positive affect, optimism, life satisfaction, health, belongingness, and autonomy. Combining the results of 79 samples that included a total of 16,416 participants, an overall positive effect size of 0.47 was found with higher levels of self-compassion being generally accompanied by higher levels of well-being. This suggests that a caring attitude towards oneself when facing adversity serves to maintain a sense of feeling comfortable, happy, and healthy in life. In a similar vein, MacBeth and Gumley25 synthesized the findings of 14 studies linking self-compassion to indices of psychopathology to obtain an average effect size of r = –0.54. This demonstrates that higher levels of this self-related trait are associated with lower symptom levels of anxiety, stress, and depression, and is in line with the notion that self-compassion may immunize individuals from developing psychological problems.26

(Dis)similarities Between Self-Esteem and Self-Compassion

Self-esteem is a concept with a fairly long research tradition: especially after Rosenberg published his seminal book in the mid-1960s,27 which also included a comprehensive scale for measuring the construct, psychologists increasingly focused on this construct in their research. This steadily culminated in an annual amount of more than 600 publications and over 26,000 citations in 2022 (in Web-of-Science using [“self-esteem” in title] as the search term), which makes self-esteem currently one of the most frequently studied concepts in psychology. The construct of self-compassion was introduced only at the beginning of the 21st century when Neff published her first papers on the topic,20,28 but its popularity is still clearly on the rise (reaching 382 publications and 10,123 citations in 2022).19,29 It is important to note here that the concept of self-compassion was partly introduced because of dissatisfaction with the construct of self-esteem. Specifically, critical scholars argued that because self-esteem is largely contingent on responses of others and events happening in life, the concept was argued to have little predictive value. It would merely reflect social status and personal failure or success, and as such it is hardly surprising that people who are marginalized, face a lot of adversity in life (eg, abuse and neglect), and suffer from psychopathological conditions, also display low levels of self-esteem.15,30 Moreover, questions were raised regarding the malleability of (low) self-esteem: for example, positive feedback, flattering, and praise are difficult to reconcile with the negative picture that people (sometimes) have about themselves and hence do not automatically result in a more positive self-view.20 Self-compassion is assumed to not have these drawbacks: This trait would be less dependent on the proceedings of life and is also thought to be more mouldable, making it a suitable target for intervention.19

Whether the critical attitude towards self-esteem and the positive stance towards self-compassion is all justified, is still a matter of debate.18,29 Fact is that both self-related concepts also share a number of important features. That is, as noted earlier, both are trait-like variables that refer to a benign psychological attribute of human beings characterized by a positive reflection about the self. Furthermore, from a theoretical point-of-view, they are both thought to promote adaptive and prosocial behaviour and as such are generally considered to be protective in nature, boosting the person’s positive affect and well-being, and preventing the development of psychological problems.

Despite these commonalities, there are also a number of notable differences between self-esteem and self-compassion. First of all, the relationship with the self is not the same for both concepts. That is, whereas self-esteem pertains to a positive evaluation of the self as compared to others or in the light of some general normative standard, self-compassion concerns a positive attitude towards the self when facing difficulties, without making any evaluative or comparative judgments.19 Second, self-esteem is more concerned with a cognitive appraisal process that – although initiating defensive reactions to maintain or even improve one’s sense of worth – by itself does not incorporate any coping mechanism.31,32 In contrast, self-compassion incorporates a positive action tendency:22 cognitive strategies, such as positive self-talk and cognitive reappraisal strategies are deployed to alleviate the suffering.33 Third and finally, self-esteem and self-compassion are thought to be mediated by different brain-based systems.34,35 In terms of Gilbert’s social mentalities theory,21,36 self-esteem seems to be more associated with an activation of the sympathetic threat system, which alerts the person for possible downward social mobility and inferiority and instigates operations of agency and competition. In contrast, self-compassion would reflect an activation of the parasympathetic soothing system, which aims to regulate negative emotions by seeking support and connection with others.6,37

Meta-Analytic Intermezzo

Given the similarities between self-esteem and self-compassion, while also acknowledging their differences, it can be expected that both constructs will be “moderately correlated”.6 Furthermore, there is a tendency in the literature to depict self-compassion as the more beneficial psychological concept,19,20,37 and so it can be predicted that self-compassion will show more robust links to indices of well-being and show greater potential for shielding against stress and other psychological problems than self-esteem. To empirically test these suppositions, we conducted a meta-analysis which has the advantage of combining the results of multiple scientific studies, thereby providing a more accurate look at these topics.38

Meta-Analytic Procedure

In the first week of March 2023 (more specific, on March 6, 2023), a literature search was conducted in Web-of-Science with [“self-compassion” in topic] AND [“self-esteem” in topic] as the search terms. The searching period was 2003 (ie, the year that the construct of self-compassion was first referred to in the scientific literature) to 2023. Wilson’s39 online meta-analysis effect size calculator was used to calculate the Fisher’s z-transformed correlation (r) and the accompanying 95% confidence interval (CI) as an effect size indicator for the correlation between self-esteem and self-compassion in each study as well as for the correlations between self-esteem and self-compassion on the one hand and each variable representing well-being or a psychological problem. Fisher’s z-transformed correlations and CIs of multiple well-being or psychological problems indicators were averaged for each study and eventually across all studies. We expected to obtain positive effect sizes for the relations between self-esteem/self-compassion and indices of well-being, whereas we anticipated negative effect sizes between both self-related concepts and measures of psychological problems.

Results of the Meta-Analysis

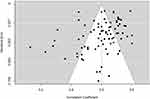

As can be seen in the PRISMA flow diagram40 (Figure 1), the literature search yielded 221 hits, which were all inspected for suitability by the first author. Seventy-six papers (including 85 samples) were identified as relevant because they included the correlation between the traits of self-esteem and self-compassion. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale27 was used in 66 of these studies (86.8%), whereas the Self-Compassion Scale28 (or its short-form41) was employed in 71 investigations (93.4%), indicating that these self-reports are the dominant measures in this research field. As can be seen in Table 1, the average correlation between self-esteem and self-compassion was positive and strong: r = 0.65, with an effect size of 0.71. Outcomes were rather heterogeneous [which may have been caused by sample differences (eg, adolescent versus adult, clinical versus non-clinical), and measures of self-esteem and self-compassion used (eg, shortened versus long version, other measures than the Neff and Rosenberg scale)] and the funnel plot (Figure 2) showed some asymmetry (rank correlation: value = −0.23, p = 0.002; regression test: value = −3.21, p = 0.001): This was mainly due to a number of investigations showing a relatively small correlation between self-esteem and self-compassion. However, none of the studies showed a result that was in contrast with the average outcome.

|

Figure 1 PRISMA flow diagram depicting the selection of articles that were included in the meta-analysis on self-esteem, self-compassion, and psychological problems/well-being. |

|

Figure 2 Funnel plot of the studies reporting on the correlation between self-esteem and self-compassion. |

Sixty-nine studies reported on the relations between self-esteem and self-compassion, on the one hand, and variables reflecting aspects of well-being (k = 45, 46 samples; eg, satisfaction with life, meaning in life, positive affect, belongingness, support, self-control, self-efficacy) and/or psychological problems (k = 69, 72 samples; eg, anxiety, depression, self-criticism, negative affect, rumination, body dissatisfaction, stress, narcissism, and anger), on the other hand. As can be seen in Table 1, both self-related constructs displayed comparable relations to indices of well-being and psychological problems. That is, the relations between self-esteem and self-compassion and well-being variables were positive, while the relations with psychological problems were negative, with all average effect sizes being quite large (ie, between |± 0.40| and |± 0.49|). Data showed again considerable heterogeneity (which is not that surprising given the large variety in well-being and psychological problems variables) although the outcomes of individual studies were generally in the same direction as the average outcomes. Note further that the obtained average effect sizes compared well with those found in previous meta-analyses investigating the effects of self-esteem and self-compassion separately.16,17,24,25

Given the overlap between self-esteem and self-compassion, we conducted an additional analysis using an online second-order partial correlations calculator (http://vassarstats.net/par2.html). With this tool, it was possible to compute correlations between self-esteem and self-compassion and other variables, while controlling for the overlap between both self-related traits. The results showed that the links of self-esteem and self-compassion with indices of well-being and psychological problems clearly attenuated when controlling for this shared variance (ie, effect sizes between |± 0.19| and |± 0.30| (Table 1 and Figure 3). However, the effect sizes of the partial correlations were of a similar magnitude for both self-related constructs and remained statistically significant, indicating that self-esteem and self-compassion each accounted for a unique proportion in the variance of well-being and psychological problems measures.

|

Figure 3 Average effect sizes (r) found for the (partial) relations between self-compassion and self-esteem, on the one hand, and indices of well-being and psychological problems, on the other hand. |

Conclusion

Altogether, the results of our meta-analysis demonstrate that the relation between self-esteem and self-compassion is quite strong and that the effect size for their correlation should be qualified as “large” rather than “moderate”.42 This signifies that – despite some unique features – the overlap between both self-related constructs is considerable and implies that in research aiming to explore the relative contributions of self-esteem and self-compassion in the prediction of well-being or psychological problems, these variables will to some extent compete for the same proportion of the variance. Nevertheless, we also noted that even when controlling for their overlap, self-esteem and self-compassion remained significant correlated to indices of well-being and psychological problems. The average effect sizes for their unique contributions were largely comparable, with statistical comparisons even indicating that self-esteem was somewhat stronger correlated to both well-being and psychological problems than self-compassion (Z’s being 10.60, p < 0.001 and 6.58, p < 0.001, respectively). Thus, no evidence was obtained to support the claim that self-compassion has more potential as a positive-protective variable than self-esteem.

Further Reflections on the Link Between Self-Esteem and Self-Compassion

The above findings warrant some further elaboration on the relation between self-esteem and self-compassion. The strong correlation points out that these two self-related constructs have much in common: Those who positively evaluate their worth as a person, will also treat themselves with kindness when facing adversities. In particular, it seem plausible that individuals with “true” self-esteem, that is, an authentic sense of self-worth that is not dependent on comparisons with others or fulfilling some general standard, will be more inclined to display self-compassionate responding in times of suffering.20 There are also empirical data to support this notion. In a longitudinal study,43 2809 adolescents completed measures of trait self-esteem and self-compassion annually for a period of four years. The results indicated that on each point in time, self-esteem and self-compassion were substantially correlated, and that across time, both self-related constructs demonstrated considerable stability. Most importantly, the data showed that self-esteem emerged as a consistent predictor of self-compassion across the four years of the study, but not vice versa. The researchers concluded that “the capacity to extend compassion toward the self depends on one’s appraisal of worthiness”,43 which suggests that self-esteem is a more generic positive trait that serves as the basis from which compassionate self-responding may develop.

Measurement issues might also be partially responsible for the observed overlap between self-esteem and self-compassion. The dominant measures in this research field – the Self-Compassion Scale (as well its short version) and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale – not only consist of items that directly measure the intended positive constructs, but also contain items that reflect their negative counterparts, ie, uncompassionate self-responding (including self-criticism, social isolation, and rumination) and lack of self-esteem.44,45 It is unclear to what extent the shared variance between the common self-esteem and self-compassion measures can be attributed to the overlap between the protective elements in both measures or to the reversed scored vulnerability components included in both scales. As an aside, it should also be noted that the inclusion of vulnerability components in measures of self-esteem and self-compassion may undermine their external validity: Relations with indices of positive psychological features of well-being could be constricted, while relations with indices of psychological problems might be inflated. In the self-compassion literature, empirical evidence exists for such an unwanted measurement artifact29,45,46 (although it has been consistently trivialized as “the differential effects fallacy” by self-compassion advocates),19,47 but in self-esteem research this issue has been largely neglected. In spite of its widespread use only relatively few scholars have taken interest in studying the unwanted effects of the inclusion of the negatively worded items in the Rosenberg scale,44,48,49 and hence this remains a timely and important topic for further scientific inquiry.

Self-Esteem–Enhancing Interventions

Numerous interventions have been proposed that aim to raise people’s self-esteem, but cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) is one of the most frequently employed methods.50 CBT is based on the notion that low self-esteem can best be seen as negative beliefs about the self (eg, “I am not good enough”, “I am not competent”, “I am unlovable”) – that originate from negative life experiences – which prompt maladaptive (ie, avoidant and unhelpful) behaviours. These maladaptive actions are likely to reinforce the negative self-beliefs and eventually the person becomes trapped in a downward spiral of dysfunctional cognition, emotion, and behaviour. During CBT, psychoeducation is provided (to enhance the person’s awareness of this vicious circle), cognitive therapy is applied (to challenge the negative beliefs and to replace these by more realistic and positive beliefs), and adaptive behaviour is practiced and reinforced. Meta-analyses have indicated that CBT is indeed quite successful in promoting self-esteem in clinical and non-clinical populations.50,51

Other interventions that have been applied to boost self-esteem include among others: reminiscence-based therapy, during which positive autobiographical memories are retrieved and discussed (this intervention was originally developed for elderly individuals52 but can also be applied to younger people);53 support groups that focus on the discussion of problems and receiving positive feedback and support from peers;54 art therapy, which involves the deployment of creative activities (such as painting, sculpture, dance, and music) to explore, express, and adjust inner thoughts and feelings, resulting in greater self-understanding and less negative emotion;55 and evaluative conditioning, which involves a computerized training during which self-related stimuli (eg, “I” or the person’s name) are systematically paired with positively valenced traits and features.56 All these treatments have indeed been demonstrated useful for enhancing self-esteem, with effect sizes in the small (ie, evaluative conditioning, reminiscence-based therapy) to moderate (ie, support groups, art therapy) range.50

Positive psychology interventions have also been put forward to promote people’s self-esteem. Such interventions have the purpose to encourage the person to discover and foster his/her character strengths, thereby increasing self-acceptance and self-worth.57 Compassion-focused treatments are a good example of a positive psychology approach, and this type of intervention has also been explored as a way to enhance self-esteem.58 For instance, Louis and Reyes59 developed an online cognitive self-compassion program for promoting self-exploration, self-awareness, self-acceptance, and self-love, positive coping, and emotion-regulation skills in young people. In a first test, the efficacy of the self-compassion program was evaluated in a sample of 192 adolescents aged 11 to 17 years who had been exposed to domestic violence.60 Half of the adolescents were randomly assigned to the experimental group, whereas the other half was allocated to the waiting list control group. It was found that adolescents in the experimental group showed a substantial increase in self-esteem, and such a positive change was not noted in the control group. Based on this result, the researchers concluded that the online self-compassion program seems to be a useful intervention for enhancing self-esteem in at-risk youth.

Meta-analyses have indicated that in both child and adult populations, various types of interventions yielded a positive effect on people’s general self-esteem, with average effect sizes being in the small to moderate range (with d’s of 0.38 and 0.21).50,61 O’Mara et al62 obtained a larger effect size (d = 0.51), but it should be noted that their analysis also included studies that examined the effects of interventions targeting one specific self-concept domain (which appears to be more effective). Interestingly, some interventions (eg, CBT) were more successful in boosting self-esteem than others (eg, reminiscence-based therapy),50 but compassion-focused treatments certainly belonged to the most powerful ones.58

Regarding the benefits of self-esteem interventions, two additional remarks are in order. First, most of the research on this topic has focused on self-esteem as the outcome variable, which is logical as promotion of this self-related concept is the primary target. However, self-esteem interventions are typically conducted in people with or at risk for mental health problems (eg, anxiety, depression, aggression). There is no meta-analysis to quantify the effects of self-esteem interventions on these secondary outcomes, but it can be expected that the magnitude of effects is somewhat smaller than that found for the primary outcome measure of self-esteem.63 Second, it has been put forward that enhancing self-esteem is not only advantageous but may also contain a risk: When levels of self-esteem become inflated and exaggerated, this might take the form of narcissism,64 which is a frequently used argument for preferring self-compassion over self-esteem interventions.19 Although research has indicated that self-esteem and narcissism are positively correlated,65 it has also been noted that this relation is quite weak and that both constructs are different in nature.66 Moreover, the danger of inadvertently enhancing self-esteem to excessively high levels seems less plausible in clinical settings where most patients display a lower sense of self-worth.

Compassion-Focused Interventions

During the past 20 years, interventions have been developed that focus on the cultivation of compassion,67 and typically such treatments can also be applied for fostering self-compassion.68,69 Well-known examples are Compassion-Focused Therapy,70 Mindful Self-Compassion,71 and Cognitively Based Compassion Training.72 Although these interventions share a number of features, such as psychoeducation on the role of (self-) compassion for people’s well-being, mindfulness exercises – which promote self-awareness and paying attention to the present moment, without judgment, and active experiential activities during which participants rehearse specific (self-) compassion strategies, there are also notable differences among them that are guided by specific theoretical underpinnings.73 This implies that there is considerable variation across treatments regarding the competencies that are targeted (eg, empathy, distress tolerance, acceptance) as well as the methods that are employed (eg, meditation, guided imagery, cognitive techniques).

With regard to the efficacy of the self-compassion treatments, two meta-analyses68,69 have demonstrated that such interventions are effective at increasing self-compassion (with g’s being 0.75 and 0.52, respectively) and decreasing various types of psychopathology indicators, such as anxiety, depression, stress, and rumination (with g’s in the 0.40–0.67 range). From these findings, it can be concluded that self-compassion is a malleable trait and that engendering compassionate self-responding also has positive effects for people’s well-being and mental health. Furthermore, a comparison of the effect sizes with those of self-esteem interventions yields the impression that it is somewhat easier to increase people’s self-compassion than to boost their self-esteem.

A few studies have directly compared the effects of self-compassion and self-esteem interventions. For example, Leary et al74 invited participants to write about a negative event that happened to them in the past. The main contrast involved participants who were prompted to think and write about themselves in a self-compassionate manner (by engaging in self-kindness and adopting a common humanity perspective and a mindful point-of-view) versus participants who were guided to think and feel positive about themselves to promote their self-esteem (by focusing on their positive characteristics and interpreting the event in a more positive way). The self-compassion intervention resulted in a more pronounced reduction of negative affect and greater self-acceptance than the self-esteem intervention. Similar results have been obtained in research comparing the efficacy of self-compassion and self-esteem interventions within the context of eating disorders and body dissatisfaction: Self-compassion–inducing writing produced more positive bodily feelings and greater reduction in eating disorder symptoms than self-esteem–inducing writing.75–77

In conclusion, while these were all studies with non-clinical samples in which a rather simple manipulation of self-compassion and self-esteem was conducted by means of writing exercises, the results nevertheless indicated that induced self-compassion is associated with better outcomes than induced self-esteem. Together with the observation that self-compassion appears easier to generate, one might conclude that interventions targeting this characteristic have greater potential for building resilience and well-being than interventions focusing on self-esteem.

Discussion

Self-esteem and self-compassion are both constructs that involve a positive attitude towards the self, which are thought to serve psychological resilience and as such play a role in the preservation of people’s mental health and well-being.78 While self-esteem is already an older concept that has been a topic of psychological investigation for more than half a century, self-compassion was only introduced some 20 years ago during the start of the positive psychology movement.79 If one wants to introduce a new psychological construct, it is always wise to point out in what way it can be differentiated from or adds something new beyond any existing concept.80 So, in the first writings on self-compassion, a comparison was made with self-esteem in an attempt to differentiate the two from one another.20 Basically, four arguments have been advanced in the literature to make the distinction between the two constructs and to contend that self-compassion has incremental value over self-esteem.

The first argument that has been made is that self-esteem and self-compassion would only be “moderately” correlated.6,20 Our meta-analysis, however, showed that the average correlation between measures of these constructs (mostly the Self-Compassion Scale and the Rosenberg scale) was quite substantial: a mean effect size of 0.71 was found, which should be interpreted as “large”. As we do note important differences between self-esteem and self-compassion (eg, self-evaluation versus self-attitude, appraisal versus coping, and sympathetic threat system versus parasympathetic soothing system), it is certainly not our intention to state that they reflect a similar construct. Meanwhile, the attempts to draw a dividing line between self-esteem and self-compassion have led to the absence of a search for a meaningful link among them. The study by Donald et al43 is interesting and important in this regard as the results suggest that self-esteem is the more basic trait providing the foundation for the more coping-oriented trait of self-compassion. This makes sense: appreciation and love prompt people to act with kindness to others, and in similar vein a sense of self-worth or self-love will enable persons to be kind and compassionate to themselves. We therefore urge for more studies on the commonalities between self-esteem and self-compassion as well as their temporal association.

The second argument refers to the claim that self-compassion continues to explain a significant proportion of the variance in well-being and psychological symptoms after controlling for levels of self-esteem.6,19,20,37 Such a result would indicate that self-compassion displays a unique link to these external variables that is not accounted for by self-esteem. Our meta-analysis indeed showed that once controlling for the shared variance between both self-related concepts, self-compassion remained significantly associated with indices of well-being and psychological symptoms, which indeed confirms that self-compassion has incremental value over self-esteem. However, the reverse was also true: when controlling for the influence of self-compassion, self-esteem also remained a significant correlate of well-being and psychological symptoms. The effects sizes documented for the independent contributions (partial correlations) to the external variables were comparable for self-esteem and self-compassion, suggesting that – besides communalities – both concepts harbour unique features that are relevant for understanding human resilience.

The third argument is concerned with intervention. It has been noted that because self-esteem is often contingent on the evaluation of others or on the fulfilment of some general standard – which are both factors outside a person’s control, it is difficult to manipulate this self-related trait. In contrast, self-compassion pertains to how people deal with themselves when they encounter adversities in life, thus referring to a personal attitude that would be more susceptible to change. Indeed, when looking at the effect sizes obtained by researchers on the malleability of both self-related traits, the conclusion seems justified that compassionate self-responding is easier to initiate by treatment than generic feelings of self-worth. This may also account for the finding that self-compassion interventions generally produce greater effects than self-esteem interventions. Assuming that self-esteem is the more basic trait that forms the foundation for self-compassion, a comparison arises with other therapeutic interventions. For example, the cognitive behavioural model of psychopathology assumes that people with emotional problems are often bothered by negative automatic thoughts that fuel disturbing emotions and lead to dysfunctional behaviour. The negative automatic thoughts are grounded in underlying personal schemas, which reflect the core beliefs about oneself, others, and the world. In CBT, therapists will usually first try to tackle the negative automatic thoughts, before addressing the fundamental schemas, which are formed early in life and formed by upbringing and prior experiences, are deeply rooted and hence more difficult to change.81 However, many CBT-oriented therapists currently adhere the notion that in the treatment of persistent emotional disorders, it is essential to not only focus on negative automatic thoughts but also to attend the underlying schemas.82 This could also be true when trying to improve self-focused characteristics: An initial intervention to improve self-compassion followed by an intervention to ameliorate self-esteem might yield superior and more lasting effects for building people’s resilience and well-being.

The fourth and final argument that has been made for preferring self-compassion over self-esteem has to do with the presumed downside of self-esteem, namely that (too) high levels of this trait are no longer protective but rather take the form of narcissistic tendencies, which have been found to be associated with a host of pathological outcomes.83 While it is true that self-esteem and narcissism are positively correlated,65 it should be noted that this link is not that strong and so this risk should not be exaggerated. Our meta-analysis of the relation between self-esteem and psychological problems still indicated a clear-cut protective effect for this self-related trait even though several studies included narcissism as an outcome variable.6,84,85 This implies that on average the positive effects mostly outweigh possible downsides of high levels of self-esteem. Moreover, it may well be the case that a strong reliance on self-compassion also comes with drawbacks. For example, it has been noted that high levels of self-compassion may be accompanied by feelings of self-pity and self-indulgence, which would undermine a person’s responsibility for his problems, and interfere with the motivation to try to change the adverse circumstances.86 There has been a consistent tendency to quickly discard this notion,19,20 but as far as we can see no empirical study can be found that has actually investigated the topic. Certainly, this is an interesting issue for further empirical scrutiny.

To take an advance on the research agenda, Figure 4 depicts a basic model in which self-esteem (true and contextual) and self-compassion (self-kindness and allied adaptive coping strategies) form a psychological buffer that promotes resilience and preserves mental well-being in time of adversity. It is assumed that there is a temporal link between self-esteem and self-compassion, in which the former serves as the foundation of the latter. Interesting, a number of studies have already explored this by testing mediation models in which self-compassion acts as the connecting variable between self-esteem (independent variable) and indices of psychological problems87,88 and well-being89 (dependent variable). Note also that the model includes potential downsides of both self-related concepts: defensiveness (including narcissistic tendencies) in the case of self-esteem and passivity (in the form of self-indulgence and self-pity) in the case of self-compassion, which may undermine the effectivity of the self-related screen against the drawbacks in life.

|

Figure 4 Model depicting the presumed role of self-esteem and self-compassion in resilience and well-being. |

Final Conclusion

In this paper, we want to put forward that self-esteem and self-compassion are relevant inter-correlated (predominantly) positive constructs that play a role in people’s resilience and maintenance of well-being, and hence provide leads for psychological interventions. Rather than creating a competition – in which it is argued that one construct (ie, self-compassion) is more important than the other (ie, self-esteem), it seems more appropriate to view both concepts as complementary. This would imply that researchers should devote more attention to the unique protective roles of self-esteem and self-compassion within a context of well-being and mental health as well as to their additive value in the treatment of people with psychological problems.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. James W. The Principles of Psychology. New York: Holt; 1890.

2. Leary MR, Tangney JP. Handbook of Self and Identity.

3. Tesser A. Constructing a niche for the self: a bio-social, PDP approach to understanding lives. Self Identity. 2002;1:185–190. doi:10.1080/152988602317319375

4. Oyserman D, Elmore K, Smith G. Self, self-concept, and identity. In: Leary MR, Tangney JP, editors. Handbook of Self and Identity.

5. Leary MR, Tangney JP. The self as an organizing construct in the behavioral and social sciences. In: Leary MR, Tangney JP, editors. Handbook of Self and Identity.

6. Neff KD, Vonk R. Self-compassion versus global self-esteem: two different ways of relating to oneself. J Pers. 2009;77:23–50. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00537.x

7. MacDonald G, Leary MR. Individual differences in self-esteem. In: Leary MR, Tangney JP, editors. Handbook of Self and Identity.

8. Orth U, Robins RW. The development of self-esteem. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2014;23:381–387. doi:10.1177/0963721414547414

9. Kuster F, Orth U. The long-term stability of self-esteem: its time-dependent decay and non-zero asymptote. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2013;39:677–690. doi:10.1177/0146167213480189

10. Deci EL, Ryan RM. Human autonomy. The basis for true self-esteem. In: Kernis MH, editor. Efficacy, Agency, and Self-Esteem. New York: Plenum Press; 1995:31–49.

11. Greenberg J, Pyszczynski T, Solomon S. The causes and consequences of a need for self-esteem: a terror manangement theory. In: Baumeister RF, editor. Public Self and Private Self. New York: Springer Verlag; 1986:189–212.

12. Pyszczynski T, Greenberg J, Solomon S, Arndt J, Schimel J. Why do people need self-esteem? A theoretical and empirical review. Psychol Bull. 2004;130:435–468. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.435

13. Leary MR, Baumeister RF. The nature and function of self-esteem: sociometer theory. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2000:1–62.

14. Leary MR, Downs DL. Interpersonal functions of the self-esteem motive: the self-esteem system as a sociometer. In: Kernis MH, editor. Efficacy, Agency, and Self-Esteem. New York: Plenum Press; 1995:123–144.

15. Baumeister RF, Campbell JD, Krueger JI, Vohs KD. Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2003;4:1–11. doi:10.1111/1529-1006.01431

16. Diener E, Diener M. Cross-cultural correlates of life satisfaction and self-esteem. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;68:653–663. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.68.4.653

17. Chen SJ, Chiu CH, Huang C. Self-esteem and depression in a Taiwanese population: a meta-analysis. Soc Behav Pers. 2013;41:577–586. doi:10.2224/sbp.2013.41.4.577

18. Orth U, Robbins RW. Is high self-esteem beneficial? Revisiting a classical question. Am Psychol. 2022;77:5–17. doi:10.1037/amp0000922

19. Neff KD. Self-compassion: theory, method, research, and intervention. Annu Rev Psychol. 2023;74:193–218. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-032420-031047

20. Neff KD. Self-compassion: an alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self Identity. 2003;2:85–102. doi:10.1080/15298860309032

21. Gilbert P. The Compassionate Mind. London: Constable & Robinson; 2010.

22. Strauss C, Taylor BL, Gu J, et al. What is compassion and how can we measure it? A review of definitions and measures. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;47:15–27. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2016.05.004

23. Raes F. The effect of self-compassion on the development of depression symptoms in a non-clinical sample. Mindfulness. 2011;2:33–36. doi:10.1007/s12671-011-0040-y

24. Zessin U, Dickhäuser O, Garbade S. The relationship between self-compassion and well-being: a meta-analysis. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2015;7:340–364. doi:10.1111/aphw.12051

25. MacBeth A, Gumley A. Exploring compassion: a meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;6:545–552. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2012.06.003

26. March IC, Chan SWY, MacBeth A. Self-compassion and psychological distress in adolescents: a meta-analysis. Mindfulness. 2018;9:1011–1027. doi:10.1007/s12671-017-0850-7

27. Rosenberg M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965.

28. Neff KD. Development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Identity. 2003;2:223–250. doi:10.1080/15298860309027

29. Muris P, Otgaar H. The process of science: a critical evaluation of more than 15 years of research on self-compassion with the self-compassion scale. Mindfulness. 2020;11:1469–1482. doi:10.1007/s12671-020-01363-0

30. Baumeister RF, Vohs KD. Revisiting our reappraisal of the (surprisingly few) benefits of high self-esteem. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2018;13:137–140. doi:10.1177/1745691617701185

31. Kermis MH. Toward a conceptualization of optimal self-esteem. Psychol Inq. 2003;14:1–26. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1401_01

32. Kermis MH, Lakey CE, Heppner WL. Secure versus fragile self-esteem as a predictor of verbal defensiveness: converging findings across three different markers. J Pers. 2008;76:477–512. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00493.x

33. Batts Allen A, Leary M. Self-compassion, stress, and coping. Soc Pers Psychol Compass. 2010;4:107–118. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00246.x

34. Klimecki OM, Singer T. The compassionate brain. In: Seppälä EM, Simon Thomas E, Brown SL, Worline MC, Cameron CD, Doty JR, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Compassion Science. New York: Oxford University Press; 2017:109–120.

35. Will GJ, Rutledge RB, Moutoussis M, Dolan RJ. Neural and computational processes underlying dynamic changes in self-esteem. eLife. 2017;6:e28098. doi:10.7554/eLife.28098

36. Gilbert P. Human Nature and Suffering. Hove: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1989.

37. Neff KD. Self-compassion, self-esteem, and well-being. Soc Pers Psychol Compass. 2011;5:1–12. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00330.x

38. Appelbaum M, Cooper H, Kline RB, Mayo-Wilson E, Nezu AM, Rao SM. Journal article reporting standards for quantitative research in psychology: the APA publications and communications board task force report. Am Psychol. 2018;73(1):3–25. doi:10.1037/amp0000191

39. Wilson DB. Practical meta-analysis effect size calculator; 2010. Availabe from https://www.campbellcollaboration.org/escalc/html/EffectSizeCalculator-Home.php.

40. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10:89. doi:10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4

41. Raes F, Pommier E, Neff KD, Van Gucht D. Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the self-compassion scale. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2011;18:250–255. doi:10.1002/cpp.702

42. Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155–159. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155

43. Donald JN, Ciarrochi J, Parker PD, Sahdra BK, Marshall SL, Guo J. A worthy self is a caring self: examining the developmental relations between self-esteem and self-compassion in adolescents. J Pers. 2018;86:619–630. doi:10.1111/jopy.12340

44. Greenberger E, Chen C, Dmitrieva J, Farruggia SP. Item-wording and the dimensionality of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale: do they matter? Pers Individ Diff. 2003;35:1241–1254. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00331-8

45. Muris P, Otgaar H. Deconstructing self-compassion: how the continued use of the total score of the self-compassion scale hinders studying a protective construct within the context of psychopathology and stress. Mindfulness. 2022;13:1403–1409. doi:10.1007/s12671-022-01898-4

46. Muris P, Otgaar H, Lopez A, Kurtic I, Van de Laar I. The (non)protective role of self-compassion in internalizing symptoms: two empirical studies in adolescents demonstrating unwanted effects of using the self-compassion total score. Mindfulness. 2021;12:240–252. doi:10.1007/s12671-020-01514-3

47. Neff KD. The differential effects fallacy in the study of self-compassion: misunderstanding the nature of bipolar continuums. Mindfulness. 2022;13:572–576. doi:10.1007/s12671-022-01832-8

48. DiStefano C, Motl RW. Personality correlates of method effects due to negatively worded items on the Rosenberg self-esteem scale. Pers Individ Diff. 2009;46:309–313. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2008.10.020

49. Quilty LC, Oakman JM, Risko E. Correlates of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale method effects. Struct Equ Modeling. 2006;13:99–117. doi:10.1207/s15328007sem1301_5

50. Niveau N, New B, Beaudoin M. Self-esteem interventions in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Res Pers. 2021;94:104131. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2021.104131

51. Kolubinski DC, Frings D, Nikcevic AV, Lawrence JA, Spada MM. A systematic review and meta-analysis of CBT interventions based on the Fennell model of low self-esteem. Psychiatry Res. 2018;267:296–305. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2018.06.025

52. Watt LM, Cappeliez P. Reminiscence interventions for the treatment of depression in older adults. In: Haight BK, Webster JD, editors. The Art and Science of Reminiscing: Theory, Methods, and Applications. Washington: Taylor & Francis; 1995:221–232.

53. Hallford DJ, Mellor D. Autobiographical memory-based intervention for depressive symptoms in young adults: a randomized controlled trial of cognitive-reminiscence therapy. Psychother Psychosom. 2016;85:246–249. doi:10.1159/000444417

54. Crabtee JW, Haslam SA, Postmes T, Haslam C. Mental health support groups, stigma, and self-esteem. J Soc Issues. 2010;66:553–569. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.2010.01662.x

55. Ching-Teng Y, Ya-Ping Y, Yu-Chia C. Positive effects of art therapy on depression and self-esteem of older adults in nursing homes. Soc Work Health Care. 2019;58:324–338. doi:10.1080/00981389.2018.1564108

56. Dijksterhuis A. I like myself but I don’t know why: enhancing implicit self-esteem by subliminal evaluative conditioning. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2004;86:345–355. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.345

57. Gable SL, Haidt J. What (and why) is positive psychology? Rev Gen Psychol. 2005;9:103–110. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.103

58. Thomason S, Moghaddam N. Compassion-focused therapies for self-esteem: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Psychother. 2021;94:737–759. doi:10.1111/papt.12319

59. Louis JM, Reyes MES. Cognitive self-compassion (CSC) online intervention program: a pilot study to enhance the self-esteem of adolescents exposed to parental intimate partner violence. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2023;28:1109–1122. doi:10.1177/13591045231169089

60. Louis JM, Reyes MES. Cognitive self-compassion (CSC) online intervention to enhance self-esteem of adolescents exposed to parental intimate partner violence in India. J Fam Trauma Child Custody Child Dev. 2023;1–18. doi:10.1080/26904586.2023.2179563

61. Haney P, Durlak JA. Changing self-esteem in children and adolescents: a meta-analytic review. J Clin Child Psychol. 1998;27:423–433. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp2704_6

62. O’Mara AJ, Marsh HW, Craven RG, Debus RL. Do self-concept interventions make a difference? A synergistic blend of construct validation and meta-analysis. Educ Psychol. 2006;41:181–206. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep4103_4

63. Bruhns A, Lüdtke T, Moritz S, Bücker L. A mobile-based intervention to increase self-esteem in students with depressive symptoms: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2021;9:e26498. doi:10.2196/26498

64. Baumeister RF, Smart L, Boden JM. Relation of threatened egotism to violence and aggression: the dark side of high self-esteem. Psychol Rev. 1996;103:5–33. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.103.1.5

65. Hyatt CS, Sleep CE, Lamkin J, et al. Narcissism and self-esteem: a nomological network analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0201088. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0201088

66. Brummelman E, Thomaes S, Sedikides C. Separating narcissism from self-esteem. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2016;25:8–13. doi:10.1177/0963721415619737

67. Kirby JN, Tellegen CL, Steindl SR. A meta-analysis of compassion-based interventions: current state of knowledge and future directions. Behav Ther. 2017;48:778–792. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2017.06.003

68. Ferrari M, Hunt C, Harrysunker A, Abbott MJ, Beath AP, Einstein DA. Self-compassion interventions and psychosocial outcomes. Mindfulness. 2019;10:1455–1473. doi:10.1007/s12671-019-01134-6

69. Wilson AC, Mackintosh K, Power K, Chan SWY. Effectiveness of self-compassion related therapies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mindfulness. 2019;10:979–995. doi:10.1007/s12671-018-1037-6

70. Gilbert P. Compassion-Focused Therapy. London: Routledge; 2010.

71. Neff KD, Germer CK. A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. J Clin Psychol. 2013;69:28–44. doi:10.1002/jclp.21923

72. Pace TWW, Negi LT, Dobson-Lavelle B, et al. Engagement with cognitively-based compassion training is associated with reduced salivary C-reactive protein from before to after training in foster care program adolescents. Psychoneuroendrocrin. 2013;38:294–299. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.05.019

73. Kirby JN. Compassion interventions: the programmes, the evidence, and implications for research and practice. Psychol Psychother. 2017;90:432–455. doi:10.1111/papt.12104

74. Leary MR, Tate EB, Adams CE, Batts Allen A, Hancock J. Self-compassion and reactions to unpleasant self-relevant events: the implications of treating oneself kindly. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;92:887–904. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.887

75. Barbeau K, Guertin C, Pelletier L, Pelletier L. The effects of self-compassion and self-esteem writing interventions on women’s valuation of weight management goals, body appreciation, and eating behaviors. Psychol Women Q. 2022;46:82–98. doi:10.1177/03616843211013465

76. Moffitt RL, Neumann DL, Williamson SP. Comparing the efficacy of a brief self-esteem and self-compassion intervention for state body dissatisfaction and self-improvement motivation. Body Image. 2018;27:67–76. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.08.008

77. Seekis V, Bradley GL, Duffy A. The effectiveness of self-compassion and self-esteem writing tasks in reducing body image concerns. Body Image. 2017;23:206–213. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.09.003

78. Muris P, Meesters C, Pierik A, De Kock B. Good for the self: self-compassion and other self-related constructs in relation to symptoms of anxiety and depression in non-clinical youths. J Child Fam Stud. 2016;25:607–617. doi:10.1007/s10826-015-0235-2

79. Bhullar N, Schutte NS, Wall HJ. Personality and positive psychology. In: Carducci BJ, Nave CS, Mio JS, Riggio RE, editors. The Wiley Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences: Models and Theories. New York: Wiley; 2020:423–427.

80. Hodson G. Construct jangle or construct mangle? Thinking straight about (nonredundant) psychological constructs. J Theor Soc Psychol. 2021;5:576–590. doi:10.1002/jts5.120

81. Beck JS. Cognitive Behavior Therapy. Basics and Beyond.

82. Young JE, Klosko JS, Weishaar M. Schema Therapy: A Practitioner’s Guide. New York: Guilford Publications; 2003.

83. Miller JD, Lynam DR, Hyatt CS, Campbell WK. Controversies in narcissism. Ann Rev Psychol. 2017;13:291–315. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045244

84. Barry CT, Loflin DC, Doucette H. Adolescent self-compassion: associations with narcissism, self-esteem, aggression, and internalizing symptoms in at-risk males. Pers Individ Diff. 2015;77:118–123. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2014.12.036

85. Mosewich AD, Kowalski KC, Sabiston CM, Sedgwick WA, Tracy JL. Self-compassion: a potential resource for young women athletes. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2011;33:103–123. doi:10.1123/jsep.33.1.103

86. Robinson KJ, Mayer S, Batts Allen A, Terry M, Chilton A, Leary MR. Resisting self-compassion: why are some people opposed to being kind to themselves? Self Identity. 2016;15:505–524. doi:10.1080/15298868.2016.1160952

87. Bugay-Sökmez A, Manuoğlu E, Coşkun M, Sümer N. Predictors of rumination and co-rumination: the role of attachment dimensions, self-compassion, and self-esteem. Curr Psychol. 2023;42:4400–4411. doi:10.1007/s12144-021-01799-0

88. Holas P, Kowalczyk M, Krejtz I, Wisiecka K, Jankowski T. The relationship between self-esteem and self-compassion in socially anxious. Curr Psychol. 2023;42:10271–10276. doi:10.1007/s12144-021-02305-2

89. Pandey R, Kumar Tiwari G, Parihar P, Kumar Rai P. Positive, not negative, self-compassion mediates the relationship between self-esteem and well-being. Psychol Psychother. 2021;94:1–15. doi:10.1111/papt.12259

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.