Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 7

Self-assessment of nursing competency among final year nursing students in Thailand: a comparison between public and private nursing institutions

Authors Sawaengdee K, Kantamaturapoj K, Seneerattanaprayul P, Putthasri W, Suphanchaimat R

Received 21 April 2016

Accepted for publication 7 June 2016

Published 8 August 2016 Volume 2016:7 Pages 475—482

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S111026

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Dr Md Anwarul Azim Majumder

Krisada Sawaengdee,1,2 Kanang Kantamaturapoj,3 Parinda Seneerattanaprayul,1 Weerasak Putthasri,1 Rapeepong Suphanchaimat,1,4

1International Health Policy Program (IHPP), 2Praboromrajchanok Institute for Health Workforce Development, Ministry of Public Health, Nonthaburi, 3Banphai Hospital, Khon Kaen, 4Department of Social Sciences, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Mahidol University, Nakhon Pathom, Thailand

Introduction and objectives: Nurses play a major role in Thailand’s health care system. In recent years, the production of nurses, in both the public and private sectors, has been growing rapidly to respond to the shortage of health care staff. Alongside concerns over the number of nurses produced, the quality of nursing graduates is of equal importance. This study therefore aimed to 1) compare the self-assessed competency of final year Thai nursing students between public and private nursing schools, and 2) explore factors that were significantly associated with competency level.

Methods: A cross-sectional clustered survey was conducted on 40 Thai nursing schools. Data were collected through self-administered questionnaires. The questionnaire consisted of questions about respondents’ background, their education profile, and a self-measured competency list. Descriptive statistics, factor analysis, and multivariate regression analysis were applied.

Results: A total of 3,349 students participated in the survey. Approximately half of the respondents had spent their childhood in rural areas. The majority of respondents reported being “confident” or “very confident” in all competencies. Private nursing students reported a higher level of “public health competency” than public nursing students with statistical significance. However, there was no significant difference in “clinical competency” between the two groups.

Conclusion: Nursing students from private institutions seemed to report higher levels of competency than those from public institutions, particularly with regard to public health. This phenomenon might have arisen because private nursing students had greater experience of diverse working environments during their training. One of the key limitations of this study was that the results were based on the subjective self-assessment of the respondents, which might risk respondent bias. Further studies that evaluate current nursing curricula in both public and private nursing schools to assess whether they meet the health needs of the population are recommended.

Keywords: public health, factor analysis, regression analysis, confidence

Introduction

It has been widely recognized that without sufficient, high-quality health workers, essential health services cannot be adequately delivered.1,2 Among various health care professionals, nurses play a major role in a health care team. Throughout the 21st century, the role of nurses has evolved dramatically. Nurses are now working in a wide variety of settings, including hospitals, classrooms, community health units, home health care, laboratories, and even in the business sector.3 As a result, many countries have boosted their production of nurses to meet the growing demand for health care in the population.4

Over the past decade, the role of private nursing schools in Thailand has been developing rapidly to keep pace with continuing growth in the country’s economy and an increasingly aged population. Accordingly, the number of new private nursing schools has grown throughout the past 15 years, from 15 in 2001 to 21 in 2015.5 The increased involvement of the private sector in nursing production might be due to the fact that the mobilization of resources in the private sector is more flexible and is less hampered by the rigid bureaucratic management which characterizes the public sector.5

While the number of health staff is always a critical concern, their quality is of equal importance. The quality of health practitioners is measured not only in their clinical skill but also through other life skill-related competencies, such as their ability to communicate with other health workers, their professionalism, and their ability to adapt learnt skills to real-world practice.6 This fact gave rise to a critical concern among policy makers in Thailand, namely, are private nursing graduates sufficiently competent to work in the Thai health care system, and how is their competency compared relative to nursing graduates from public institutions? There is only a limited existing literature comparing competency of nurses between the public and private sectors. One example, Pillay7 investigated management skill among nursing managers in South Africa. The study revealed that the level of competency reported by public sector managers was lower than that reported by private sector managers. However, the study did not directly explore the aspects of competency other than managerial skill and also faced a key limitation of having a small number of respondents.7

Thus, the main objectives of this study were 1) to compare the competency level of final year nursing students between public and private nursing schools in Thailand and 2) to determine and explore the factors associated with nursing competency. Note that the term competency, applied in this study, was in essence the self-assessment of the respondents of their confidence in performing a wide range of skills, which is explained in the “Methods” section.

Methods

Study design, population, and sample size

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Institute of the Development of Human Research Protections, Thailand.

Cross-sectional survey was employed. Several rounds of face-to-face meetings between senior officers of the Ministry of Public Health (MOPH) and representatives from the Thailand Nursing and Midwifery Council (TNMC) were conducted between July 2011 and March 2012 to craft the questionnaire, to ensure the questionnaire’s validity (content validity), and to outline the analysis plan. In 2012, at the commencement of this study, there were a total of 78 nursing schools in Thailand. Five of these 78 schools were newly established and therefore did not have final year students. Accordingly, the study focused only on 73 schools, which already had final year students.

A simple two-staged cluster sampling was applied. Nursing schools were regarded as cluster samples, and all final year students in the selected schools were designated as elementary sampling units. To ensure the representativeness of the respondents, the number of schools participating in the study was grossly estimated at 40 (∼55% of the 73 available schools). Considering maximal variability, these 40 schools were selected according to the number of schools by region and by school affiliation (Table 1). Data collection was performed during February to March 2012.

| Table 1 Details of the 40 nursing schools enrolled in the study by school location and affiliation Note: The number in parentheses is the total number of nursing schools in each category. |

Questionnaire design and distribution

The research team adapted the questionnaire from the annual surveys of new medical and dental graduates, which have been conducted annually since 2010, by the International Health Policy Program, MOPH.8 The questionnaire was composed of two parts: 1) the demographic data and education profile of the respondents and 2) a self-assessment of professional nursing competencies.

In the first part, the respondents were asked about their sex (male vs female), age, and location of residence during their early years (1–15 years old) of life (urban vs rural). Note that a respondent’s residence was considered “urban” if it was located in either Greater Bangkok (Bangkok plus two surrounding provinces: Nonthaburi and Samut Prakarn) or the municipal district of any other province, all other locations were considered “rural.” The questions about education profile consisted of 1) school location (Bangkok vs outside Bangkok), 2) school affiliation (public vs private), and 3) mode of admission of participants (national entrance exam vs non-national entrance modes, eg, regional quota or special talent quota).

In the second part, the respondents were asked to measure their confidence in 14 different competencies, namely, 1) maintaining professional standards, 2) provision of clinical nursing care, 3) health promotion and disease prevention, 4) coping with new emerging diseases, 5) evidence-based nursing care, 6) systematic thinking, 7) working with diverse communities, 8) addressing population health, 9) collaborating with other health workers in a health care team, 10) leading a health care team, 11) promoting a safe environment, 12) multicultural understanding, 13) keeping pace with health care technology, and 14) life-long learning skill. The measurement was arranged in Likert scale, ranging from 1, “least confident”, to 5, “most confident”.

After the questionnaire was crafted, a pilot test of the questionnaire was performed with 30 final year nursing students in one of the private nursing schools in Bangkok. The reliability test yielded Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.79, which implied acceptable reliability. Then, a total of 4,954 self-administered questionnaires were distributed to all 40 selected schools by the TNMC, through local coordinators. The local coordinators were instructed to survey all the final year students of each selected school at the commencement ceremony, which allowed the coordinators to enroll a large number of students to the survey. However, the participation in the survey was voluntary. The participating students were instructed about the meaning and how to complete the questionnaire and were assured that their confidentiality would be strictly kept according to the standard research ethics. No stipend was given to the students for their participation in the survey or for completing the questionnaire, but payment of administrative costs was made to local coordinators, according to the number of questionnaires returned to the research team. All participants provided written informed consent.

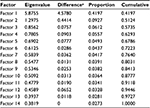

Data analysis

STATA XI software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used to analyze the data. The analysis comprised four steps. First, descriptive statistics were used to explore demographic information, education profile, and the self-assessed degree of confidence in various competencies. Results were shown by mean and frequency. Second, the 14 competencies were grouped by factor analysis with Varimax rotation in order to join together competencies with relatively similar characteristics. Factors with eigenvalue >1 would be used in the further analysis. Third, a competency (factor) score produced by Bartlett’s formula was assigned to all competency groups, which had an eigenvalue >1.9 Univariate analysis by student’s t-test was exercised to determine differences in competency score between students from different school types. In the final step, the score was assessed against school affiliation by multivariate regression analysis. The respondents’ demographic and education profiles were included in the analysis as covariates. A P-value of 0.05 was used as a cutoff point for assessing statistical significance. A variance constant estimate was applied in estimating robust standard errors, taking into account the cluster effect.

Results

Demographic profile of respondents

A total of 3,349 respondents participated in the study (response rate =67.6%). Before analyzing the data, the returned questionnaires were routinely cleaned and checked for duplication. The data cleaning found no duplicated questionnaires, and there was(were) no respondent(s) who gave the same answer to all competency questions, which might undermine the result accuracy. Overall, approximately 26.9% (n=902) of the returned questionnaires were completed by students from private nursing schools, and one-third (33.4%) were from nursing schools established in Bangkok. The majority of the respondents were female (94.8%) with the mean age of 23 years. Approximately half of the respondents had rural backgrounds and were admitted to nursing school through national entrance examination. While individual student profiles were quite similar, patterns of mode of admission and school location were markedly different between public and private nursing schools. Students enrolled through the national entrance exam were more concentrated in public nursing schools than in private nursing schools (50.6% vs 29.3%). Nursing schools outside Bangkok were more likely to operate in the public sector (72.6%) than in the private sector (50.4%) (Table 2).

| Table 2 Profiles of respondents Note: Missing data are small in number; therefore, they were not included in the analysis. |

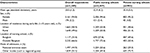

Competency level

In general, most respondents reported themselves “confident” (scale 4) or “very confident” (scale 5) in each competency. The mean score of self-assessed competency ranged from 3.5 to 4.3. “Maintaining professional standards”, “working with diverse communities”, and “collaborating with other health workers in a health care team” were the topics with the highest mean score; meanwhile, “coping with new emerging diseases” had the lowest mean score. Private nursing students tended to report having higher competency than students from public nursing schools; however, the difference between the two groups was trivial (<0.1). The complete list of each competency with its mean score is provided in Table 3.

| Table 3 Mean score of each competency level Note: Data presented as mean (standard deviation). |

Factor analysis and factor loading

Table 4 demonstrates findings from (unrotated) factor analysis, and Table 5 presents the factor loading (pattern matrix) after rotation. Of the 14 factors identified, only two yielded an eigenvalue of >1 (5.9 and 1.3). Factor 1 seemed to be loaded by competencies that are relevant to life skills for public health activities such as “working with diverse communities”, “multicultural understanding”, and “lifelong learning skill”. In contrast, factor 2 appeared to be loaded by mainstream clinical-related skills, such as “maintaining professional standards” and “provision of clinical nursing care”. To better reflect the characteristics of the loading components, factor 1 was renamed “public health competency”, and factor 2 was renamed “clinical competency”. More details of the results of the analysis are shown in Tables 4 and 5.

| Table 5 Factor loading matrix Note: The bold entries refer to which factor the given competency was assigned. |

Constructing factor score

A (standardized) competency score was calculated for “public health competency” and “clinical competency” by Bartlett’s formula. A higher score reflected a higher level of competency. Univariate analysis showed that private nursing students reported significantly higher levels of competency in “public health competency” than public nursing students (P=0.012). This difference also appeared in “clinical competency” but with less statistical significance (Table 6).

Multivariate analysis

Multivariate regression analysis was applied. The competency score produced in the previous step was regressed on the independent variables, namely, “location of residence during early years”, “mode of admission”, “location of nursing schools”, and “school affiliation”.

Table 7 presents findings from multivariate regression analysis of “public health competency”. Graduating from private nursing schools yielded a significant positive effect on public health competency (P=0.005). The participants enrolled in schools through national entrance examination, and those graduating from nursing schools in Bangkok seemed to report lower levels of competency, with statistical significance, than those without such determinants (P=0.029 and 0.011, respectively).

| Table 7 Multivariate analysis of “public health competency” Notes: *Statistical significance at 95% level of confidence. **Statistical significance at 99% level of confidence. R2=0.006. Abbreviation: SE, standard error. |

None of the independent variables showed a significant effect on the score for clinical competency at the cutoff P-value of 0.05. Nonetheless, by considering a less stringent cutoff at P-value of 0.10, admission through national entrance exams and studying in private nursing schools had a positive influence on the score (with P=0.087 and 0.072, respectively). Other covariates did not demonstrate a statistical impact on the score (Table 8).

| Table 8 Multivariate analysis of “clinical competency” Note: R2=0.002. Abbreviation: SE, standard error. |

Discussion

This study contributed to knowledge of the competencies of private and public nursing students in Thailand. It appeared that graduates from private nursing schools were of equal or even greater competence than those from the public sector, particularly in the public-health-related competency. This finding also indicated to policy makers, or health educationists, how to make the best use of private nursing graduates in public health activities in the Thai health care system. Moreover, the study also found that there were some factors that had a positive influence on public health competency, which in this case were non-national entrance exam admission and graduating from nursing schools outside Bangkok. Yet, such influences were less apparent in clinical-skill-related competencies.

The study team identified some key explanations of the above phenomenon. First, most private nursing institutions in Thailand have only been established in the past decade. Some institutions do not have their own health facilities or do not have enough internal capacity to provide essential training for their students. The TNMC accreditation and quality assurance process require that nursing institutions provide adequate training hours for students; accordingly, some private nursing students are sent for further training at health facilities that are allied to their nursing school. These other facilities may be either publicly or privately run hospitals. This indirectly provides better opportunities for students from private institutions to experience diverse working environments and to become familiar with the health care system in both the public and private arenas. An obvious example is seen at one of the private nursing schools in Bangkok, where students are obliged to practice their clinical years at a wide range of working sites, from subdistrict health centers to public community hospitals and large urban (tertiary) hospitals.10,11 This situation is quite different from the training system in public institutions, which normally only perform training within their own facilities (due to their larger training capacity and routine subsidy from the government).

A byproduct finding of this study was the fact that graduating from a school outside Bangkok and having been admitted through a track other than the routine entrance examination had a positive influence of public health competency. Since there are no community hospitals in Bangkok, students in the capital city might have fewer opportunities to experience community health work or to work cooperatively with other health cadres who do not normally work in the university setting, such as public health volunteers, community health workers, and primary care doctors. In addition, non-national entrance admission tracks are usually tied to a special requirement that students need to spend their clinical years working in remote communities. This is a requirement that many institutions have implemented in response to an MOPH policy, which seeks to foster positive attitudes toward working in rural areas among health practitioners, and thereby to encourage them to help fill posts in underserved areas after graduating. This system has proved, at least partially, successful in addressing health workforce shortages, particularly shortages of doctors, over the past two decades.12–14

Second, contradicting the common perception of students in the private sector as coming from affluent families, approximately 40% of private nursing students were not fully financially supported to study by their own family and therefore had to borrow funding from various sources. This was particularly true of those from rural backgrounds; by contrast <20% of the nursing students from MOPH training institutes sought an education loan.15 Sawaengdee15 suggested that there were a significant number of private nursing students who had positive attitudes toward and were willing to engage in the nursing profession, despite facing financial difficulties and having fewer chances to gain admission into publicly operated schools. This might make them more confident in performing public health work, which requires greater involvement with multiple stakeholders than general clinical work.15

For clinical competency, the level of confidence of private nursing students seems to be on a par with those from public institutions. The rigorous accreditation and quality assurance of the Thai nursing education system may account for this finding. Health professional training in Thailand is regulated by two main authorities: 1) the Office of the Higher Education Commission and Office for National Education Standards and Quality Assessment, within the Ministry of Education, which regulates the standard of higher education in all fields (not just for health professionals), and 2) the professional councils, which impose detailed standard requirements for specified professional fields (such as the Thai Medical Council and the Thai Dental Council).16 All nursing institutions, whether in the public or the private sector, must meet the standards stipulated by the TNMC prior to the school’s establishment and must regularly renew their license every 3–5 years.17 Moreover, the Dean Consortium and professional associations also take part in curriculum review through regular meetings. The primary focus of accreditation is still clinically oriented to ensure the production of qualified nurses. However, there has been an increasing concern that there should be a mechanism to ensure that new graduates really contribute to the improvement of Thai health care system and address the population’s health needs, rather than merely being qualified to the curriculum standard.18

The aforementioned explanations are still hypothetical assumptions, which require further exploration. More in-depth qualitative works that delve into the details of the nursing curriculum in both public and private nursing schools are recommended.

Despite a rigorous study design, this study still faced some critical limitations, and readers should be reminded of some key methodological weaknesses and potential biases before applying the results to the real world. First, although using self-assessment was a convenient means of evaluating competency, its results might not truly reflect the students’ competency. Respondent bias could occur at every step of data collection. Students in private nursing schools might tend to report more positively than those in public institutions because they had to pay more for their training. Further studies that apply objective assessment rather than subjective assessment of students’ competency should be conducted, and the findings of this study should be validated against the results of any future study of this type. Second, it is very likely that there were some important factors such as different teaching styles between schools, the educational background of students during high school, and current academic performance that were not included in the questionnaire, and thus were left out from the analysis. The questionnaire used in the next round of this survey should be designed more meticulously and should seek to be more comprehensive. Third, due to limited time and resources, the distribution and the return of questionnaires depended on the compliance of local coordinators; as a result, the study faced difficulties in ensuring methodological soundness. Information and selection biases might occur if the local coordinators indirectly influenced how the respondents completed the questionnaire. This is an important factor for the research team that should be considered when developing a more stringent methodology for conducting future studies.

Conclusion

Students from private nursing institutions reported higher levels of competency than public nursing students, especially regarding the public health competency. The rigorous accreditation and quality assurance systems of the TNMC, the Office of the Higher Education Commission, and the Office for National Education Standards and Quality Assessment are mechanisms that ensure the quality of training in both public and private institutions. A key potential explanation for the higher self-reported level of the public health competency in private nursing students is that the private nursing students tended to have more opportunities to work in diverse environments, which helped expose them to a wide range of health cadres, and health service systems, ranging from subdistrict health centers to tertiary hospitals, and in both public and private settings. Future studies that attempt to explore the details of the curriculums of both public and private nursing schools are recommended. In addition, future studies should assess whether, and to what extent, the existing curriculum helps produce quality graduates with sufficient skills and the potential to address the health needs of the population and contribute to the Thai health care system as a whole.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Doctor Viroj Tangcharoensathien for his unrelenting support and invaluable advice throughout the study course. We also greatly appreciate the support received from International Health Policy Program staff in their efforts to collect the data; and we would like to express our gratitude for the support received from senior advisors in the Resilient and Responsive Health Systems (RESYST) research consortium, particularly, Professor Kara Hanson, Doctor Duane Blaauw, and Doctor Mylene Lagarde. We are also very grateful to Mr Alexander Dalliston for his assistance in language editing. The study was supported by the RESYST research consortium, the Thai Health Promotion Foundation, and the International Health Policy Program Foundation.

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

De Savigny D, Adam T. Systems Thinking for Health Systems Strengthening. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. | ||

Nelson EC, Godfrey MM, Batalden PB, et al. Clinical microsystems, part 1. The building blocks of health systems. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34(7):367–378. | ||

Tingen MS, Burnett AH, Murchison RB, Zhu H. The importance of nursing research. J Nurs Educ. 2009;48(3):167–170. | ||

Martinez-Gonzalez N, Djalali S, Tandjung R, et al. Substitution of physicians by nurses in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):214. | ||

Thailand Nursing and Midwifery Council. Annual Report. Bangkok: Jundthong Printing, TNMC; 2015. | ||

Finocchio LJ, Bailiff PJ, Grant RW, O’Neil EH. Professional competencies in the changing health care system: physicians’ views on the importance and adequacy of formal training in medical school. Acad Med. 1995;70(11):1023–1028. | ||

Pillay R. The skills gap in nursing management in South Africa: a sectoral analysis: a research paper. J Nurs Manag. 2010;18(2):134–144. | ||

Wisaijohn T, Suphanchaimat R, Topothai T, Seneerattanaprayul P, Pudpong N, Putthasri W. Confidence in dental care and public health competency during rural practice among new dental graduates in Thailand. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2015;6:1–9. | ||

Di Stefano C, Zhu M, Mîndrilă D. Understanding and using factor scores: considerations for the applied researcher. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2009;14(20):1–11. | ||

School of Nursing Rangsit University. Course specification; 2014 [cited February 7, 2015]. Available from: http://www.rsu.ac.th/academic/tqf/file_upload/20140829104104.docx. Accessed February 7, 2015. | ||

School of Nursing Rangsit University. Nursing science program; 2010 [cited February 7, 2015]. Available from: www.rsu.ac.th/academic/file/curriculum/02_nurse.doc. Accessed February 7, 2015. | ||

Putthasri W, Suphanchaimat R, Topothai T, Wisaijohn T, Thammatacharee N, Tangcharoensathien V. Thailand special recruitment track of medical students: a series of annual cross-sectional surveys on the new graduates between 2010 and 2012. Hum Resour Health. 2013;11:47. | ||

Tangcharoensathien V, Limwattananon S, Suphanchaimat R, Patcharanarumol W, Sawaengdee K, Putthasri W. Health workforce contributions to health system development: a platform for universal health coverage. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91(11):874–880. | ||

Suphanchaimat R, Wisaijohn T, Thammathacharee N, Tangcharoensathien V. Projecting Thailand physician supplies between 2012 and 2030: application of cohort approaches. Hum Resour Health. 2013;11(1):3. | ||

Sawaengdee K. The influence of rural background on the return to practice in rural areas of new nursing graduates Paper presented at: The Annual Academic Conference; 2013; Khon Kaen. | ||

Office of Higher Education Commission. National standard framework for assessing higher education degree and its practical guideline; 2009 [cited February 7, 2015]. Available from: http://graduateschool.bu.ac.th/tqf/images/pdf/tqf_th.pdf. Accessed February 7, 2015. | ||

Thailand Nursing and Midwifery Council. List of institutions and nursing and midwifery curricula that have been accredited by the Council (only the institutes with nursing graduates); 2015 [cited February 7, 2015]. Available from: http://www.tnc.or.th/files/2010/12/page-448/__66735.pdf. Accessed February 7, 2015. | ||

Asia Pacific Action Alliance on Human Resources for Health (AAAH). Report to the Prince Mahidol Award Conference (PMAC) Requesting Support for the AAAH Protocol Development Workshop. Bagnkok: AAAH; 2012. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.