Back to Journals » Journal of Pain Research » Volume 10

Retention of finger blood flow against postural change as an indicator of successful sympathetic block in the upper limb

Authors Nakatani T, Hashimoto T, Sutou I, Saito Y

Received 13 October 2016

Accepted for publication 20 January 2017

Published 28 February 2017 Volume 2017:10 Pages 475—479

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S124627

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Dr Michael Schatman

Toshihiko Nakatani,1 Tatsuya Hashimoto,2 Ichiro Sutou,2 Yoji Saito3

1Department of Palliative Care, Shimane University Faculty of Medicine, Izumo, 2Palliative Care Center, Shimane University Hospital, Izumo, 3Department of Anesthesiology, Shimane University Faculty of Medicine, Izumo, Japan

Background: Sympathetic block in the upper limb has diagnostic, therapeutic and prognostic utility for disorders in the upper extremity that are associated with sympathetic disturbances. Increased skin temperature and decreased sweating are used to identify the adequacy of sympathetic block in the upper limb after stellate ganglion block (SGB). Baroreflexes elicited by postural change induce a reduction in peripheral blood flow by causing sympathetic vasoconstriction. We hypothesized that sympathetic block in the upper limb reduces the decrease in finger blood flow caused by baroreflexes stimulated by postural change from the supine to long sitting position. This study evaluated if sympathetic block of the upper limb affects the change in finger blood flow resulting from postural change. If change in finger blood flow would be kept against postural changes, it has a potential to be a new indicator of sympathetic blockade in the upper limb.

Methods: Subjects were adult patients who had a check-up at the Department of Pain Management in our university hospital over 2 years and 9 months from May 2012. We executed a total of 91 SGBs in nine patients (N=9), which included those requiring treatment for pain associated with herpes zoster in seven of the patients, tinnitus in one patient and upper limb pain in one patient. We checked for the following four signs after performing SGB: Horner’s sign, brachial nerve blockade, finger blood flow measured by a laser blood flow meter and skin temperature of the thumb measured by thermography, before and after SGB in the supine position and immediately after adopting the long sitting position.

Results: We executed a total of 91 SGBs in nine patients. Two SGBs were excluded from the analysis due to the absence of Horner’s sign. We divided 89 procedures into two groups according to elevation in skin temperature of the thumb: by over 1°C (sympathetic block group, n=62) and by <1°C (nonsympathetic block group, n=27). Finger blood flow decreased significantly just after a change in posture from the supine to long sitting position after SGB in both groups. In the sympathetic block group, the ratio of finger blood flow in the long sitting position/supine position with a change in posture significantly increased after SGB compared with before SGB (before SGB: range 0.09–0.94, median 0.53; after SGB: range 0.33–1.2, median 0.89, p<0.0001).

Conclusion: Our study shows that with sympathetic block in the upper limb, the ratio of finger blood flow significantly increases despite baroreflexes stimulated by postural change from the supine to long sitting position. Retention of finger blood flow against postural changes may be an indicator of sympathetic block in the upper limb after SGB or brachial plexus block.

Keywords: sympathetic block, baroreflex, stellate ganglion block, peripheral blood flow, thermography

Introduction

In clinical pain management and in patients with peripheral circulatory disorders, sympathetic block in the upper limb is commonly used for diagnostic, therapeutic and prognostic purposes for disorders associated with sympathetic disturbances in the upper extremity. During stellate ganglion block (SGB), as well, it is important to assess whether the sympathetic nerve is blocked or not. Increased skin temperature and decreased sweating are used to identify the adequacy of sympathetic block in the upper extremity. However, this requires a thermography device to precisely evaluate skin temperature, a diaphoremeter to measure sweating, and an equipment to assess the sympathetic skin response.1

In general, when changing from the supine to sitting position, baroreflexes elicited by the postural change induce a reduction in peripheral blood flow by increasing the sympathetic tone of peripheral blood vessels.2 Sympathetically mediated cutaneous vasoconstriction directly reduces peripheral blood flow. This can be measured using a laser blood flow meter. However, peripheral blood flow measurements by laser flowmetry may be unstable under certain autonomic nervous conditions. We previously reported a preliminary study describing the potential of retention of finger blood flow against postural change to become a new indicator of sympathetic block in the upper limb.3 This novel method for assessing successful sympathetic block uses blood flowmetry in association with baroreflexes induced by postural changes. We hypothesized that sympathetic block in the upper limb reduces the decrease in finger blood flow caused by baroreflexes associated with postural change from the supine to long sitting position (i.e. sitting with the lower limbs stretched out in front of the subject). This study evaluated whether or not sympathetic block in the upper limb affects the change in finger blood flow with postural change. If change in finger blood flow would be kept against postural changes, it has a potential to be a new indicator of sympathetic blockade in the upper limb.

Methods

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Shimane University Faculty of Medicine. Subjects were adult patients who had a check-up at the Department of Pain Management in our university hospital over 2 years and 9 months from May 2012. We received written informed consent from all patients for participation in the study. Nine patients, five males and four females, aged 44–80 years (mean age 62.3 years, standard deviation 13.3), required treatment by SGB. The diagnoses were herpes zoster pain in seven of the patients, tinnitus in one patient and upper limb pain in one patient. The patients had no history of orthostatic intolerance, such as orthostatic hypotension and related diseases affecting the sympathetic nervous system, or disordered circulation in the upper limb, and were not on prescription vasoactive, cardiac or sweating-related medication.

Each patient was positioned supine with the cervical spine in the neutral position, and SGB was performed by an anterior approach under ultrasound guidance. A microconvex transducer (S-Nerve; SonoSite Co. Ltd., Bothell, WA, USA) with a 5–8 MHz resolution was used to scan the C6 vertebral level. The local anesthetic, namely, 5 mL of 1% mepivacaine (AstraZeneca Co. Ltd., Osaka, Japan), was injected into the longus colli muscle under the prevertebral fascia using a 25-gauge and 25 mm long needle with an in-plane approach in the sagittal plane.

Thereafter, the following four parameters were assessed in all patients:

Horner’s sign. After SGB, we checked for the presence of myosis, ptosis and enophthalmos. This was assessed to identify successful block of the cervical sympathetic trunk.

Presence of brachial nerve block to exclude sympathetic block in the upper limb due to inadvertent brachial plexus block. In patients in whom it did occur, a significant increase in blood flow to the fingers of the blocked hand was observed throughout the period of brachial plexus anesthesia.4 We checked if brachial nerve block was present or not.

Skin temperature of the thumb on the blocked side by thermography before SGB and 20 min after SGB. An indicator of sympathetic block in the upper limb is elevated skin temperature of over 1°C relative to before SGB.5

Blood flow in the ball of the thumb on the SGB side. This was measured using a laser blood flow meter (Laser Doppler ALF 21D, ADVANCE Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) in the supine position and immediately after changing to the long sitting position (the lowest finger blood flow), before SGB and 20 min after SGB.

Laser Doppler flowmetry is an excellent noninvasive technique for the measurement of cutaneous microcirculation.6,7 For this, laser Doppler probes were attached to the ball of the thumb to measure cutaneous microcirculation. The ball of the thumb, which is considered to be the most peripheral region in the upper limb, has relatively thick subcutaneous tissue. The thickness of the subcutaneous tissue is well suited for the measurement of finger blood flow by laser Doppler as affected blood flow by vasoconstriction. Stable finger blood flow over 10 s was measured in the supine position. Finger blood flow just after changing to the long sitting position was measured as the lowest blood flow within the first 15 s of the postural change. The results of blood flow measurements, measured by laser flowmetry, were expressed as mL·min−1·100 g tissue−1. When changing from the supine to long sitting position, the upper limb was stretched out along the trunk, parallel to the torso and vertical to the bed. This meant that the hand position was not changed in both the supine and long sitting positions.

Finger blood flows were compared between the supine and long sitting positions before SGB and 20 min after SGB. Next, we calculated the finger blood flow ratio as (the lowest finger blood flow in the long sitting position)/(finger blood flow in the supine position) both before and after SGB. We evaluated the difference in finger blood flow ratios before and after SGB. Statistical analysis of the data before and after SGB was performed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Stat view for Macintosh (version 5.0; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. p-Values <0.01 were considered to be significant.

Results

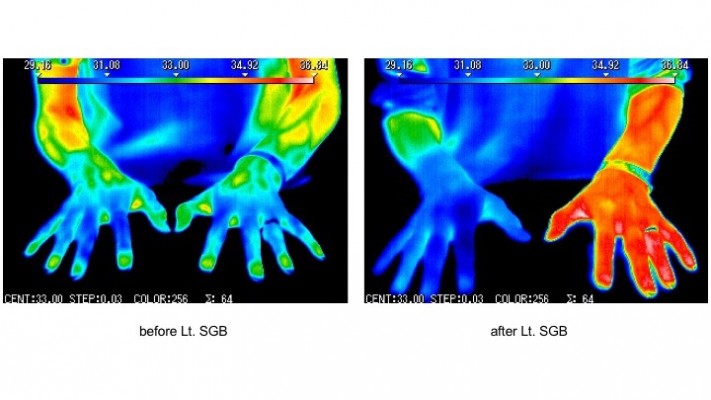

We executed a total of 91 SGBs in nine patients. Two SGBs were excluded from the analysis because of the absence of Horner’s sign (Table 1). Bleeding as a complication during and after the procedure did not occur in any of the procedures. We divided 89 procedures into two groups based on whether the skin temperature increased by more or less than 1°C. The group of 62 SGBs, in which the skin temperature increased by more than 1°C, was considered as the successful sympathetic block in the upper limb group. The group of 27 SGBs, in which the skin temperature increased by <1°C, was considered the nonsympathetic block group. Figure 1 demonstrates a case with effective sympathetic block in the upper limb as measured by thermography. Immediately after a change in posture from the supine to long sitting position, absolute finger blood flow in both groups decreased significantly before and after SGB (Table 2). In the nonsympathetic block group, the ratio of (finger blood flow in the long sitting position)/(finger blood flow in the supine position) in the thumb on the SGB side did not increase significantly with a change in posture after the block compared with the ratio before SGB (Table 3; Figure 2A). However, in the sympathetic block group, the ratio after SGB increased significantly with a change in posture compared with the ratio before SGB (Table 3; Figure 2B).

| Figure 1 Thermography showing elevation in skin temperature in the upper limb by over 1ºC following SGB Abbreviation: SGB, stellate ganglion block. |

| Table 2 Finger blood flow Notes: Unit of blood flow: mL·min−1, 100 g tissue−1. Comparison between supine and sitting by Wilcoxon signed-rank test. *p<0.0001. Abbreviation: SGB, stellate ganglion block. |

| Table 3 The ratio of finger blood flow Notes: Comparison of the ratio between before and after SGB by Wilcoxon signed-rank test. *p<0.0001. Abbreviation: SGB, stellate ganglion block. |

Discussion

Sympathetic blocks, such as SGB, are widely used for the treatment of pain and sympathetic disorders of the head, neck and upper extremities. Recently, ultrasound-guided techniques have allowed for a more effective and precise sympathetic blocking, and may improve the safety of the procedure by direct visualization of vascular and soft tissue structures.8 The anatomical basis of this technique is that the cervical sympathetic trunk lies entirely subfascially.9 The stellate ganglion, formed by fusion of the inferior cervical and first thoracic ganglia, is located adjacent to the neck of the first rib, lateral to the longus colli muscle and posterior to the vertebral artery.10 In the method of ultrasound-guided SGB reported by Shibata et al, the tip of the needle penetrates the prevertebral fascia in the longus colli muscle and 8 mL of 1% lidocaine is injected.11 They demonstrated how ultrasound-guided C6-SGB is performed beneath the prevertebral fascia in the longus colli muscle. Another study reported that a 2 mL dose is sufficient for a successful block when performing an ultrasound-guided SGB.12 Following the report of Narouze et al,13 we typically use 5 mL of the local anesthetic for ultrasound-guided SGB.

Reliable methods of evaluation of the success of sympathetic block after SGB are, therefore, essential. The signs of a successful SGB are Horner’s triad of myosis, ptosis and enophthalmos, and lack of sweating on the face on the block side, due to blockade of the cervical sympathetic trunk. The other signs are venodilatation and absence of sweating in the upper limb, and increase in skin temperature of the blocked limb by at least 1°C, since SGB also affects the upper limb region.5 The most commonly used method for assessing successful sympathetic block of the upper limb is measurement of the temperature of the skin. Skin temperature assessment with an infrared thermometer is a reliable early indicator of a successful block after brachial plexus block.14

Other techniques include measurement of skin resistance and the sweat test. Of the tests employed to assess sympathetic block, temperature measurement is probably the most widely used technique to assess sympathectomy of the affected site.15 However, since temperature measurement may be affected by the environment of the clinical room, ensuring that the room temperature remains stable is important for precise measurements, as compared with measuring blood flow by laser flowmetry.

We previously reported that retention of finger blood flow against postural change has the potential to be a new indicator of sympathetic block in the upper limb.3 In that report, the number of procedures in which the ratio of (finger blood flow in the long sitting position/finger blood flow in the supine position) was >90%, which was significantly higher on the SGB as compared to the non-SGB side.3 In this study, we divided SGBs into two groups depending on whether skin temperature increased by more or less than 1°C after the block. Elevation of skin temperature by more than 1°C was assumed to indicate successful sympathetic block in the upper limb after SGB. In both the groups of this study, there was a significant difference in blood flow between the supine and long sitting positions both before and after SGB. However, the ratio of blood flow in (long sitting position/supine position) significantly increased after SGB. Sympathetic nerve block in the upper limb induced by SGB prevents efferent nerve conduction to the peripheral nerves of vessels and, hence, postural change-induced vasoconstriction. It, thus, induces peripheral vasodilation in the upper extremity and maintains blood flow in the face of postural change. The fact that the ratio of finger blood flow increased after SGB indicates that sympathetic block in the upper limb cut off baroreflexes in the upper body and maintained peripheral blood flow in the thumb against postural changes.

Tschakovsky and Hughson reported that venous emptying serves as a stimulus for transient (within 10 s) vasodilation in vivo and this vasodilation can substantially elevate arterial flow.16 They studied arm elevation above the heart level in the sitting position, which is different from the supine and long sitting positions assessed in our study. We assessed and compared finger blood flow before and after SGB under the same conditions. The results of Tschakovsky’s report differ from the findings of our study, likely because we performed the study without employing a venous emptying procedure.

Szili-Torok et al reported that determination of baroreflex-induced microvascular responses might serve as a feasible method for monitoring the effectiveness of sympathetic block during axillary brachial plexus block.17 They opined that measurement of blood flow was more reliable for assessing reflex responses than for evaluating sympathetic block. In their method, cutaneous vascular resistance was calculated to evaluate sympathetic activity. With our method, it is possible to evaluate sympathetic block in the upper limb merely by using laser flowmetry to assess the change in finger blood flow following postural change.

Conclusion

Our study shows that when the sympathetic nerves in the upper limb are blocked, the ratio of finger blood flow in long sitting/supine position increases significantly despite baroreflexes stimulated by postural change from the supine to long sitting position. Retention of finger blood flow against postural changes may serve as an indicator of sympathetic blockade in the upper limb after SGB or brachial plexus block.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Vetrugno R, Liguori R, Cortelli P, Montagna P. Sympathetic skin response: basic mechanisms and clinical applications. Clin Auton Res. 2003;13(4):256–270. | ||

Stewart JM. Mechanisms of sympathetic regulation in orthostatic intolerance. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2012;113(10):1659–1668. | ||

Nakatani T, Miyamoto T, Hashimoto T, Saito Y. Retention of finger blood flow against postural change has the potential to become a new indicator of sympathetic block in the upper limb – a preliminary study. Int J Anesth Anesthesiol. 2015;2:25. | ||

Cross GD, Porter JM. Blood flow in the upper limb during brachial plexus anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 1988;43(4):323–326. | ||

Rathmell JP. Chapter 10. Stellate ganglion block. Atlas of Image-Guided Intervention in Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2012:152–161. | ||

Eun HC. Evaluation of skin blood flow by laser Doppler flowmetry. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13(4):337–347. | ||

Wright CI, Kroner CI, Draijer R. Non-invasive methods and stimuli for evaluating the skin’s microcirculation. J Pharmacol Toxicol Method. 2006;54(1):1–25. | ||

Narouze S. Ultrasound-guided stellate ganglion block: safety and efficacy. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2014;18(6):424. | ||

Gofeld M, Bhatia A, Abbas S, Ganapathy S, Johnson M. Development and validation of a new technique for ultrasound-guided stellate ganglion block. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2009;34(5):475–479. | ||

Peng PW, Narouze S. Ultrasound-guided interventional procedures in pain medicine: a review of anatomy, sonoanatomy, and procedures Part I: nonaxial structures. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2009;34(5):458–474. | ||

Shibata Y, Fujiwara Y, Komatsu T. A new approach of ultrasound-guided stellate ganglion block. Anesth Analg. 2007;105(2):550–551. | ||

Lee MH, Kim KY, Song JH, et al. Minimal volume of local anesthetic required for an ultrasound-guided SGB. Pain Med. 2012;13(11):1381–1388. | ||

Narouze S, Vydyanathan A, Patel N. Ultrasound-guided stellate ganglion block successfully prevented esophageal puncture. Pain Physician. 2007;10(6):747–752. | ||

Minville V, Gendre A, Hirsch J, et al. The efficacy of skin temperature for block assessment after infraclavicular brachial plexus block. Anesth Analg. 2009;108(3):1034–1036. | ||

Elias M. Cervical sympathetic and stellate ganglion blocks. Pain Physician. 2000;3(3):294–304. | ||

Tschakovsky ME, Hughson RL. Venous emptying mediates a transient vasodilation in the human forearm. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279(3):1007–1014. | ||

Szili-Torok T, Paprika D, Peto Z, et al. Effect of axillary brachial plexus blockade on baroreflex-induced skin vasomotor responses: assessing the effectiveness of sympathetic blockade. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2002;46(7):815–820. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.