Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 9

Relationship among temporary separation, attachment styles, and adjustment in first-grade Iranian children

Authors Tahmasebi S, Mafakheri Bashmaq S, Karimzadeh M, Teymouri R, Amini M, vaghefi MSM, Mazaheri MA

Received 5 April 2016

Accepted for publication 20 September 2016

Published 8 December 2016 Volume 2016:9 Pages 339—346

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S109875

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Siyamak Tahmasebi,1 Saman Mafakheri Bashmaq,2 Mansoureh Karimzadeh,3 Robab Teymouri,4 Mahdi Amini,5 Maryam Sadat M vaghefi,6 M Ali Mazaheri7

1Department of Preschool Education, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran; 2Department of Psychology and Exceptional Children’s Education, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Allameh Tabataba’i University, Tehran, Iran; 3Department of Preschool Education, Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran; 4Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran; 5Addiction Department, Center of Excellence in Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, Institute of Tehran Psychiatry, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran; 6Department of Speech Therapy, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran; 7Department of Clinical Psychology, Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran

Abstract: If mothers work outside the home, some degree of mother–child separation will be experienced and mother–child attachment will be affected. In this study, regarding the attachment styles, sociobehavioral problems in first-grade children with experience of preschool and in those taught by their mothers at-home are compared. A casual-comparative method was used to compare children in the two groups. A total of 320 first-grade children participated in the study. The study measures included a separation anxiety test, an adaptive behavior scale, and a children’s symptom inventory. Data were analyzed using multivariate statistics. Secure attachment in the group with experience of preschool was significantly higher than that in the at-home group. None of the variables, including parents’ education and father’s income, significantly affected attachment style. Neither father’s education, father’s income, or attachment significantly influenced adjustment. Father’s education significantly influenced children’s symptoms. Attachment style and hours of preschool attendance had no effect on Child Symptom Inventory scores. Associations among age at joining preschool, attachment style, and behavioral and adaptive problems in first-grade children were nonlinear and multivariate. By taking into account parents’ awareness, sensitivity, and responsiveness, relative welfare, appropriate quality of child-care centers, and having fewer hours of preschool attendance, the risk factors for early parent–child separation and institutional care can be reduced.

Keywords: separation, attachment, adjustment, pathological symptoms, first-grade children

Introduction

One of the most important changes in modern societies is the increasing number of mothers working outside the home while their child is in the first months of its life. Official statistics estimate maternal employment rates at ~70% in industrialized countries.1 Working mothers must also typically perform housekeeping duties. Such multiple responsibilities are often compounded by inflexible career programs, affecting mother–child relationships; thus, mothers inevitably rely upon child day-care centers or relatives and acquaintances to care for their children during working hours.

The notion that daily mother–child separation affects a child’s future has been the subject of much research. Bowlby2,3 has emphasized the importance of the mother–child relationship, claiming that a warm, intimate, continuous relationship with one’s mother or primary caregiver is essential for health. According to him, many forms of personality disorders result from the deprivation of parental care or inconsistencies in the parent–child relationship.2,3 Object relations theorists believe in the mother–child relationship and the key role of the mother in child development to the extent that some of them, such as Winnicott, believe that, at the beginning of life, the baby without a mother does not exist.4 Shaver and Mikulincer suggest that early attachment experiences affect future cognition and emotional–behavioral modes.5 Findings reveal that early contact between mother and child shapes social behavior in adulthood and forms the nervous system processes associated with social interaction.6 Ainsworth et al observed infants with three attachment patterns, including securely attached infants, insecure-avoidant infants, and insecure-ambivalent infants.7

Various surveys reveal that secure attachment with parents is associated with positive representations of oneself and higher self-esteem and self-efficacy.8 Negative behavior and maladjustment are less frequent in securely attached than in insecurely attached or avoidant children.9 High levels of parental responsiveness to children aged 9 months predict higher levels of secure attachment at the age of 2 years and lower levels of negative behavior at the same age. Negative behavior in children younger than 2 years of age is usually observed in those with insecure attachment to parents.10

Several studies have emphasized that quality of parental care could exacerbate behavioral issues in adolescents. A harsh upbringing and lack of discipline in parenting style are found in families with rebellious teenagers. In particular, parental rejection during childhood can predict external problems in adolescence.11–13 As these children interpret the mother’s absence as rejection, frequent, temporary separation may damage the attachment relationship.14

Some research studies, particularly those conducted before 1980, challenged these findings. In some, daily separation reportedly had no harmful effects on the child’s attachment.15–17 Children who entered kindergarten in the early years and spent a long time interacting with their peers were in a better socioemotional position.18,19 In a study by Birashk on the effects of preschool education on social adjustment of children in the first grade, training improved social adjustment in students, relative to the control group.19 However, Belsky argues that children whose mothers work long hours during the day outside the home run the risk of insecure attachment with their child.20,21 According to a study by Khanjani, children who are separated from their mothers daily at an early age, compared with children who are separated (from their mothers) at an older age, are more liable to insecure attachment and their social adaptation is less successful than their peers.15 Another research has tried to discover the cause of these contradictory findings by going beyond kindergarten linear effects and has attempted to examine the relationship between day-care and temporary factors that affect a child’s development.22

Some organizations, such as the Social Welfare Organization in Iran, emphasize the importance of increasing the number of children in preschool training programs from the current 20% thus also increasing mother–child separation.23,24 The rationale for the present study is that parents and caregivers are concerned about the mental health of preschool children and the importance of creating and maintaining a secure attachment with them. Attachment will be evaluated by comparing social and behavioral problems in first-grade children attending child-care centers and those trained by their mothers.

Materials and methods

The study was retrospective in nature, with two target and comparison groups. The target group was composed of first-grade students with preschool experience; control group members had not attended preschool. The independent variable was daily mother–child separation as a result of preschool attendance.

Sampling method

Participants

The study sample consisted of first-grade children from nonprofit and government elementary schools in Tehran, Iran, in 2012.

Sampling and selection criteria

The children were selected using a multistage cluster random sampling method. A total of 320 first-grade students were selected from eight schools. They were assigned to one of two groups: 160 to the target group and 160 to the control group. There were 20 people in each group at each school. They had preschool experience. Inclusion criteria for the target group included parental education, parents being alive, and lack of mental health disorders. The control group was selected according to the factors influencing attachment. They had no preschool experience.

Instruments

Preliminary researcher-made questionnaire

This questionnaire was designed to assess demographic variables and some independent variables, such as parents’ education and occupation, housing conditions, number of children, and gender. In the case of attending preschool, it evaluated duration, age at joining preschool, mother–child separation history, age at separation from parents, and family history of psychiatric disorders.

Separation Anxiety Test (SAT)

The Seattle version of the SAT (Slough N, Goyette M, Greenberg M. Scoring Indices for the Seattle Version of the Separation Anxiety Test. Unpublished manuscript, University of Washington, 1988), the modified version of the SAT designed by Bowlby and Klagsbrun25 for children aged 4–7 years, consists of six pictures of scenes in which parents are leaving their children. Three pictures show severe separation conditions, such as a scene in which parents go on vacation for 2 weeks and leave their child, and three pictures depicting more moderate separation. Pictures are shown separately to children. After an introductory explanation about each card image, the researcher tries to recognize the children’s reactions and feelings about the separation (Slough et al, unpublished manuscript).25

The scoring procedure is based on the types of images and responses for every picture. The scoring index for the SAT is considered a measure of the internal practical pattern of parent–child attachment. In fact, if the child forms an effective, accessible, and responsive pattern of relating to their attachment figure, it is expected that the child will be securely attached and exhibit confidence and positive feelings in situations of mild separation. In difficult separation situations, it is expected that securely attached children will have concerns, fears, and negative emotions and will express them freely. The three major components of the scoring indices of children’s responses include

- The child’s ability to express his/her vulnerability (anxiety, regret, etc.) or the child’s ability to talk about needs and separation-related issues, which is known as attachment.

- The child’s ability to express his/her self-reliance, such as having good and positive feelings at the time of separation and self-handling more or less independently at separation, which is known as self-reliance.

- Child’s avoidance of talking about separation, which is known as avoidance or avoidant-confused.

In the indices system of SAT, every response is initially classified into one of the five main categories: 1 – attachment; 2 – self-reliant; 3 – attachment/self-reliant; 4 – avoidant; and 5 – avoidant-confused.

In the next step, after placing each of the six responses into one of the five main categories, each subject’s responses are placed into 21 subcategories (such as attachment typical response, high attachment response, unusual response, …, bizarre response), based on specific criteria. Separate scores are given to each of these subgroups in terms of three grading scales: attachment, self-reliance, and avoidance. The measure includes a 4-point scale of attachment, a 4-point scale of self-reliance, and a 3-point scale of avoidance. The three scales (attachment, self-reliance, and avoidance) are used to calculate three scores for each participant. The subject’s attachment pattern is obtained by comparing scores, and the subject is placed in one of the classes: secure attachment, ambivalent, unorganized-unregulated (ambivalent/ avoidant), and avoidant.15 The test pictures were revised for the first time by Khanjani in Iran and adapted to the cultural and religious conditions of Iran.15

Children’s Adaptive Behavior Scale

The Adaptive Behavior Scale – Public School version was developed in 1974 by Lambert et al,26 for 7- to 13-year-old American children and translated and standardized by Shahni Yaylagh,27 for 1500 Iranian girls and boys. This questionnaire has 11 main areas, 38 subcategories, and 260 questions. Moreover, another standardized questionnaire, including educational and family characteristics of participants, was prepared. This additional questionnaire contains information on the first and last name, school name, class name, parents’ occupation, parents’ educational level, and status of time spent at preschool of the child.21 This scale is appropriate not only for diagnosing children with learning disabilities but also for providing a behavioral profile as opposed to a single score, thus providing useful descriptive information for improving adaptive behavior. In addition, its diagnostic information can be used for class placement and planning. The scale is composed of two parts: the first part deals with issues related to development and evaluation of individual skills and habits; the second part is designed to measure maladaptive behaviors associated with personality and behavioral disorders. The questions have two response options: “sometimes” and “frequently”. Higher scores on this scale indicate less social adjustment, and lower scores indicate greater social adjustment.

A simultaneous method was used to confirm the reliability and validity of this scale. The scale is composed of three forms. In addition to Form 1, Forms 2 and 3 were also prepared. The validity of the main Form, along with Forms 2 and 3, was calculated separately for boys and girls. In the girls’ group, the validity of Form 1 with Form 2 was 0.49, and the validity of Form 1 with Form 3 was 0.57, both of which were significant (p<0.001). The reliability coefficient of this scale in the girls’ group was obtained as 0.80 using the split-half coefficient. In the boys’ group, validity of the Form 1 along with Form 2 was 0.52, and for Form 1 along with Form 3 it was 0.62, both of which were significant (p<0.001). The scale reliability coefficient in the boys’ group was calculated as 0.88 using the split-half method (Slough et al, unpublished manuscript).

Child Symptom Inventory (CSI-4)

In 1994, the American Psychiatric Association published the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-4)28 and applied some changes to the CSI-3R questionnaire. Gadow and Sprafkin prepared the CSI-4 questionnaire, which included both parent and teacher checklists. The parents’ checklist included 97 organized questions measuring 17 disorders; the teacher’s checklist included 77 organized questions, which measured 13 disorders. CSI-4 included a 115-page manual that briefly examined child psychiatric disorders and provided information on how to attain and score the reliability and validity of the instrument.29,30 The disorders were scored by the CSI-4 inventory using two methods: classification based on cutoff score and severity of symptoms. Test–retest reliability was 99%. Professors and professionals in psychology and psychiatry confirmed its validity; the validity of its association with the other results was at least 95%.

The research procedure

This study was conducted in southern and northern districts of Tehran, Iran. Four schools were randomly selected from each district. These four schools included two primary schools for boys and two primary schools for girls. In each group, a government and a nongovernment school were selected. A total of 20 students per school took part based on the inclusion criteria defined for the target group. The control group was selected from the same school, according to the factors influencing attachment. Finally, the questionnaires were administered to both the groups.

Methods of data analysis

In this research, because of the large number of variables and the existence of primitive and continuous variables, several statistical methods were used to analyze the data. The methods of statistical analysis included stepwise regression, hierarchical regression, multivariate analysis of covariance, and the correlation matrix.

Ethical considerations

The Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran gave approval for conducting this study. Written informed consent was obtained from all adult participants and the parent/s or guardian/s of all child participants.

The most important moral principles, which were taken into consideration in this study, were as follows:

- Obtaining informed consent from research participants before entering into the study.

- Respecting the participants’ rights during the research.

- Delivering the results to the schools as practical short reports after conducting the research.

Results

According to Table 1, the mean age, gestational age, father’s income, and parents’ education in children attending preschool were greater than those in children who had not attended preschool. However, students who had not attended preschool obtained a higher birth weight and age of losing a parent than those who had entered kindergarten.

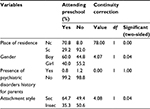

As shown in Table 2, 92.4% of children living in the north of city and 30.4% of children living in the south of the city attended kindergarten. Of the children who entered kindergarten, 70.8% were from the north of city, and 29.2% lived in the south of the city. A total of 8% of children not attending kindergarten lived in the north of the city, and 92% of children in the south. In total, 58% of children from both the regions attended kindergarten.

| Table 2 Bivariate analysis of the demographic data of groups Note: Significant difference (p<0.05). Abbreviations: Nc, north of city; Sc, south of city; Sec, secure; Insec, insecure. |

In children who participated in this study, 64.9% of boys and 50% of girls had entered preschool, and 60% of children attending kindergarten were boys, and 40% of preschool children were girls.

It was found that 50% of psychiatric disorders were related to parents of children who went to kindergarten and another 50% to parents of children who had not gone to kindergarten; 8% of preschool children had parents with psychiatric disorders. Of the 64.7% of preschool children, 49.4% of those who had not attended kindergarten exhibited secure attachment. In total, 64.1% of securely attached children had attended preschool, and 35.9% had attended kindergarten.

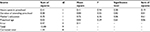

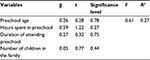

According to Table 3, none of the variables had a significant effect on type of attachment. Table 4 shows that none of the variables, such as preschool age and duration of attending preschool, had a significant effect on CSI. According to Table 5, multiple linear regression test results show that none of the variables including preschool age (p=0.78), hours spent in preschool (p=0.27), duration of attending preschool (p=0.75), and number of family children (p=0.44) are unable to predict children’s social adjustment (p>0.05).

| Table 3 The effect of independent variables on type of attachment Notes: R2 =0.696 (adjusted R2 =0.393); significant difference (p<0.05). |

| Table 4 The effect of independent variables on CSI scores Notes: R2 =0.758 (adjusted R2 =−0.455); significant difference (p<0.05). Abbreviations: CSI, Child Symptom Inventory. |

Discussion

Unexpectedly, the findings of this study showed that preschool children scored higher on measures of secure attachment (Table 2). History of kindergarten attendance had no significant effect on behavioral adjustment in later years (Table 5). In this regard, it can be argued that despite the insistence of Bowlby and Ainsworth31,32 on the importance of maternal and healthy care of children rather than inappropriate institutional care, and their warnings of the emotional/developmental long-term effects of day care on child development, even infants entrusted to day-care centers for only a few hours daily still attach to their parents rather than to their temporary caregivers.33

| Table 5 Multiple linear regression predicting children’s social adjustment Note: Significant difference (p<0.05). |

Also, it has been shown that entrusting children to kindergarten after 12 months of age has no adverse effects on them, as long as the day-care center is qualified (e.g., equipped with full-time staff who takes the child’s needs into consideration). Research has focused on children who started day care before 12 months of age; these children may tend to have avoidant-insecure attachment to their parents. Nevertheless, apparently such risk can be compensated for by sensitive and responsive parents and by good quality day-care centers, the latter of which are unfortunately scarce.34,35 The findings of the present study elucidate the positive effects of preschool care on secure attachment in the following ways.

First, studies reporting the relationship between kindergarten and attachment have found that the rate of insecurity in infants attending day-care centers was not significantly more than that in infants not entering kindergartens (36% vs. 29%) but that this rate was similar to that in industrialized countries. In fact, most infants whose mothers worked were securely attached. Furthermore, none of the research reported that there were differences in quality of attachment styles between these two situations.36,37

Second, because of family circumstances affecting security of attachment, many working mothers found it stressful to deal with two full-time jobs (at work and at home). Some mothers, because of fatigue and strained personal resources, are less kind to their children, placing them at risk of insecure attachment. Other working mothers might value the independence of their children and encourage it or, as their children have become used to separation from their parents, are unafraid of the strange situation. In such cases, remote attachment could be an index of healthy self-determination, and not of insecure attachment.38

Parents choose and build directly upon their children peer communication, indirectly influencing norms and beliefs about appropriate social behaviors and communication models based on attachment experiences. Type of attachment determines the form of communication.39,40

Third, an inferior preschool is likely to play an auxiliary role in creating insecure attachments in infants whose mothers are employed. The NICHD study—the largest longitudinal study to date, including 1000 infants and their mothers in ten districts across the country—revealed that kindergarten alone had no effect on insecure attachment but that when the children were exposed to a combination of risk factors both at home and in a child-care center (heartless nursing at home, long hours in the nursery), their insecurity increased.35 High levels of parent responsiveness in the 9-month-olds is directly associated with higher levels of emotional support from parents during preschool and high degrees of social competence in preschool children.41

Fourth, assessment of attachment security, although infants are compatible with child care, does not provide an accurate picture. When children enter kindergarten and experience a new routine entailing daily separation from their parents, it is expected that they show distress. After a few months, infants who participate in high-quality desirable programs become calmer: they smile, play, seek consolation from their caregivers, and begin to interact with their peers.

Finally, the NICHD study findings suggest that upbringing impacts problem behaviors of preschool children more than do day-care centers. Indeed, the possibility of establishing a warm and intimate relationship with an affectionate professional nurse can be very helpful for a child who has an insecure relationship with one or both parents. When these children were followed throughout preschool and early school years, it was found that they had greater confidence and better social skills than children with insecure attachments who did not attend kindergarten.22 Positive social relationships are an important source of self-esteem. As supportive intimate relationships with parents are important, a positive relationship with peers may also have a significant impact on self-esteem.42

According to Table 3, in relation to the effect of mother’s education on attachment type, although in most cases there was an emphasis on the correlation of education level with quality of attachment, in the final analysis it can be said that education affects the child’s attachment type not only directly but also through its impact on the style of care and on the mother’s parenting. However, the responsiveness and sensitivity of caregivers in contact with their children are more important than merely education and are important contributors to secure or insecure attachment.43 So, age at mother–child separation and level of education or literacy are weak variables in this equation. Likewise, level of education and hours spent in preschool are more important determinant factors than age at mother–child separation. Many studies confirm these findings.14,15,20,34–37,44,45 In addition, mother–child relationship type and quality impact children’s behavioral adjustment in school and kindergarten. According to Table 4, adjustment is affected by factors including age of attending preschool, state of attending preschool, and duration of preschool. It cannot be said that children who are under noninstitutional care experience more appropriate social adjustment at school than children under institutional care. Family economic status, father’s education, and child attachment emerged as far more important to child adjustment than whether a child attends preschool, consistent with some research findings.7,46–48

Therefore, children who had attended preschool, because of the education and economic status of their parents, typically experience secure attachment. Because of the attachment type, hours spent in day care, and fathers’ education and economic status, they likely exhibit fewer behavioral disorders and better adjustment, consistent with previous work.15,16,19,34,36,37,45–47 Gormley et al demonstrated the importance of preschool program and its influence on enhancement of socioemotional development of children.49

Limitations

- This study included children aged only from 6.8 to 7.8 years. The results therefore cannot be generalized to younger or older age groups. Conclusion about the short- and long-term effects of separation age in addition to kindergarten starting time thus cannot be drawn.

- This research was conducted from 2011 to 2012, and all subjects were tested over a defined period of time. Because this study was analytical and correlational and the results of the study have not been affected by the passage of time, also they have not dealt with the issue of prevalence, the same relationship can exist between the variables during years. So, it seems the date of conducting project is not old.

- The results related to the child’s attachment pattern were obtained by using a SAT, a pictorial projective tool answered by children. The tool might evoke clichéd answers from children and the results might thus inaccurately represent real attachment patterns.

- This study is ex post facto in nature: data were collected with a view to the past.

- The questionnaire designed for adaptive behavior should have been completed by parents, as their knowledge about their children is vast, but as access to all parents was not available, the questionnaires had to be completed by teachers who did not have accurate information about all students.

Conclusion

The relationships among age at mother–child separation, age at joining a nursery school or child-care center, attachment styles, behavioral disorders, and adjustment in first-grade children are nonlinear and multivariate. Taking account of the awareness, sensitivity, and responsiveness of care of parents, relative welfare, appropriate quality of child-care centers, and hours spent in child-care centers, the risk factors for early parent–child separation and institutional care can be reduced.

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Fogel A. Infancy: Infant, Family, and Society. St. Paul (MN): West Publishing Co; 1991. | ||

Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss: Vol. 2: Separation. London: Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis; 1973. | ||

Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss. Separation, Anxiety and Fear. New York: Basic Books; 1973. | ||

Winnicott DW. The Family and Individual Development. London: Routledge; 2012. | ||

Shaver PR, Mikulincer ME. Human Aggression and Violence: Causes, Manifestations, and Consequences. Washington (DC): American Psychological Association; 2011. | ||

Branchi I, Curley JP, D’Andrea I, Cirulli F, Champagne FA, Alleva E. Early interactions with mother and peers independently build adult social skills and shape BDNF and oxytocin receptor brain levels. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(4):522–532. | ||

Ainsworth M, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall SN. Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation. Hillsdale (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum; 1978. | ||

Mattanah JF, Lopez FG, Govern JM. The contributions of parental attachment bonds to college student development and adjustment: a meta-analytic review. J Couns Psychol. 2011;58(4):565. | ||

Main M, Kaplan N, Cassidy J. Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: a move to the level of representation. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 1985;50:66–104. | ||

Rispoli KM, McGoey KE, Koziol NA, Schreiber JB. The relation of parenting, child temperament, and attachment security in early childhood to social competence at school entry. J Sch Psychol. 2013;51(5):643–658. | ||

Sousa C, Herrenkohl TI, Moylan CA, et al. Longitudinal study on the effects of child abuse and children’s exposure to domestic violence, parent-child attachments, and antisocial behavior in adolescence. J Interpers Violence. 2011;26(1):111–136. | ||

Dogan SJ, Conger RD, Kim KJ, Masyn KE. Cognitive and parenting pathways in the transmission of antisocial behavior from parents to adolescents. Child Dev. 2007;78(1):335–349. | ||

Trentacosta CJ, Shaw DS. Maternal predictors of rejecting parenting and early adolescent antisocial behavior. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2008;36(2):247–259. | ||

Cohen NJ, Farnia F. Children adopted from China: attachment security two years later. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2011;33(11):2342–2346. | ||

Khanjani Z. Relation between contemporary mother-child separation with attachment figure and childrens behavioral problems. JLS. 2002;45(2–3):127–162. | ||

Khanjani Z. Attachment Pathology and Development. Tabriz, Iran: Forouzesh Publication; 2005. | ||

Khanjani, Z. [Evolution and Pathology of Attachment from Childhood to Adolescence]. Tabriz, Iran: Froozesh Publication; 2011. Persian. | ||

Scarr S, Phillips D, McCartney K. Facts, fantasies and the future of child care in the United States. Psychol Sci. 1990;1(1):26–35. | ||

Birashk B, Moradi S. Assessment of Relationship Between Preschool Educations with Social Adjustment of First-Grade Children in Tehran City. Tehran, Iran: University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences; 2003. | ||

Belsky J, Rovine MJ. Nonmaternal care in the first year of life and the security of infant-parent attachment.Child Dev. 1988;59(1):157–167. | ||

Isabella RA, Belsky J. Interactional synchrony and the origins of infant-mother attachment: a replication study.Child Dev. 1991;62(2):373–384. | ||

Egeland B, Hiester M. The long-term consequences of infant day-care and mother-infant attachment. Child Dev. 1995;66(2):474–485. | ||

[Day Care Centers]. State Welfare Organization of Iran; 1999. Available from: http://www.behzisti.ir. Accessed April 5, 2016. Persian. | ||

[The affairs of kindergarten]. Welfare Organization of Tehran Province; 2010. Available from: http://www.behzistitehran.org.ir/. Accessed April 5, 2016. Persian. | ||

Klagsbrun M, Bowlby J. Responses to separation from parents: a clinical test for young children. Br J Projec Psychol Person Stud. 1976;21(2):7–27. | ||

Lambert NM. Manual: AAMD Adaptive Behavior Scale: Public School Version: 1974 Revision. Washington (DC): American Association on Mental Deficiency; 1975. | ||

Yaylagh MBS. [Normalizing adaptive behaviour scale for elementary students]. J Educ Psychol. 1995;3:1–2. Persian. | ||

Association AP. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association; 1994:471–475. | ||

Gadow K, Sprafkin J. Adolescent Symptom Inventory-4 Norms Manual. Stony Brook (NY): Checkmate Plus; 1998. | ||

Gadow KD, Sprafkin JN. Child Symptom Inventory 4: Screening and Norms Manual. Stony Brook (NY): Checkmate Plus; 2002. | ||

Ainsworth MS, Bowlby J. An ethological approach to personality development. Am Psychol. 1991;46(4):333. | ||

Bowlby J, Ainsworth MDS. Maternal Care and Mental Health. New York: Jason Aronson; 1995. | ||

Clarke-Stewart A. Day care: a new context for research and development. In: Perlmutter M, editor. Parent-Child Interaction and Parent-Child Relations in Child Development. Hillsdale (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1984. | ||

Rutter M, O’Connor TG. Implications of Attachment Theory for Child Care Policies; 1999. | ||

Weinfield NS, Sroufe LA, Egeland B, Carlson E. Individual differences in infant-caregiver attachment: conceptual and empirical aspects of security. In: Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications. Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. New York: The Guilford Press; 2008:73–95. | ||

The NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Familial factors associated with the characteristics of nonmaternal care for infants. J Marriage Fam. 1997;59(2):389–408. | ||

Roggman LA, Langlois JH, Hubbs-Tait L, Rieser-Danner LA. Infant day-care, attachment, and the “File Drawer Problem”. Child Dev. 1994;65(5):1429–1443. | ||

Lamb ME, editor. The development of father–infant relationships. In: The role of the father in child development, 3rd ed. Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley & Sons Inc.; 1997:104–120. | ||

Ennett ST, Karl EB, Vangie AF, Michael P, Katherine AH. Parent-child communication about adolescent tobacco and alcohol use: what do parents say and does it affect youth behavior? J Marriage Fam. 2001;63(1):48–62. | ||

Meeus W, Oosterwegel A, Vollebergh W. Parental and peer attachment and identity development in adolescence. J Adolesc. 2002;25(1):93–106. | ||

Gorrese A, Ruggieri R. Peer attachment: a meta-analytic review of gender and age differences and associations with parent attachment. J Youth Adolesc. 2012;41(5):650–672. | ||

Mota CP, Matos PM. Peer attachment, coping, and self-esteem in institutionalized adolescents: the mediating role of social skills. Eur J Psychol Educ. 2013;28(1):87–100. | ||

Ding YH, Xu X, Wang ZY, Li HR, Wang WP. Study of mother–infant attachment patterns and influence factors in Shanghai. Early Hum Dev. 2012;88(5):295–300. | ||

Weinfield NS. Attachment and the Representation of Relationships from Infancy to Adulthood: Continuity, Discontinuity and Their Correlates. St. Paul (MN): University of Minnesota; 1996. | ||

The NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Child Care and Child Development: Results from the NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. | ||

Owen MT, Cox MJ. Marital conflict and the development of infant–parent attachment relationships. J Fam Psychol. 1997;11(2):152. | ||

Thompson RA, Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Early sociopersonality development. In: Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development, Vol 3., 5th ed. Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley & Sons Inc.; 1998:25–104. | ||

Gaussen T. Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol. 3: Social, Emotional and Personality Development. Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons; 1998: reprinted 2001, Cambridge University Press. | ||

Gormley WT Jr, Phillips D, Newmark K, Welti K, Adelstein S. Social-emotional effects of early childhood education programs in Tulsa. Child Dev. 2011;82(6):2095–2109. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.