Back to Journals » Open Access Rheumatology: Research and Reviews » Volume 9

Recommendations for optimizing methotrexate treatment for patients with rheumatoid arthritis

Authors Bello AE, Perkins EL, Jay R, Efthimiou P

Received 5 January 2017

Accepted for publication 8 February 2017

Published 31 March 2017 Volume 2017:9 Pages 67—79

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/OARRR.S131668

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Chuan-Ju Liu

Alfonso E Bello,1 Elizabeth L Perkins,2 Randy Jay,3 Petros Efthimiou4

1Illinois Bone & Joint Institute, Glenview, IL, 2Rheumatology Care Center, Birmingham, AL, 3Arizona Arthritis & Rheumatology Associates, Phoenix, AZ, 4Division of Rheumatology, New York Methodist Hospital, Brooklyn, NY, USA

Abstract: Methotrexate (MTX) remains the cornerstone therapy for patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), with well-established safety and efficacy profiles and support in international guidelines. Clinical and radiologic results indicate benefits of MTX monotherapy and combination with other agents, yet patients may not receive optimal dosing, duration, or route of administration to maximize their response to this drug. This review highlights best practices for MTX use in RA patients. First, to improve the response to oral MTX, a high initial dose should be administered followed by rapid titration. Importantly, this approach does not appear to compromise safety or tolerability for patients. Treatment with oral MTX, with appropriate dose titration, then should be continued for at least 6 months (as long as the patient experiences some response to treatment within 3 months) to achieve an accurate assessment of treatment efficacy. If oral MTX treatment fails due to intolerability or inadequate response, the patient may be “rescued” by switching to subcutaneous delivery of MTX. Consideration should also be given to starting with subcutaneous MTX given its favorable bioavailability and pharmacodynamic profile over oral delivery. Either initiation of subcutaneous MTX therapy or switching from oral to subcutaneous administration improves persistence with treatment. Upon transition from oral to subcutaneous delivery, MTX dosage should be maintained, rather than increased, and titration should be performed as needed. Similarly, if another RA treatment is necessary to control the disease, the MTX dosage and route of administration should be maintained, with titration as needed.

Keywords: bioavailability, dosing, gastrointestinal, polyglutamation, subcutaneous

Plain language summary

Methotrexate is one of the mainstays of treatment for rheumatoid arthritis. It reduces pain and swelling and can slow joint damage and disease progression over time. Most rheumatologists use methotrexate as initial therapy for patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and most patients take it by mouth. Typically, people will start with a weekly dose of 7.5–10 mg and the dose might be raised to 25 mg/wk. There is a relationship between methotrexate dose and its effectiveness for treating the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis. When methotrexate pills do not control the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis, it can be administered by an injection beneath the skin. With this approach, more drug reaches the blood without increasing side effects. For some patients, methotrexate alone is not sufficient to control symptoms no matter how it is delivered. In these cases, it can be given with other drugs, including sulfasalazine and/or hydroxychloroquine. Methotrexate might also be combined with biologic medications that include tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and agents that target other inflammatory cells and molecules, such as abatacept and tocilizumab. Regardless of how methotrexate is administered or combined with other medications, taking it as prescribed is essential for gaining and maintaining control over rheumatoid arthritis.

Introduction

Methotrexate (MTX) remains the anchor disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). MTX has multiple mechanisms of action that contribute to improvement in clinical symptoms and disease control in patients with RA, including inhibition of inflammatory cell proliferation, interference with T-cell activity and cytokine secretion, and augmented release of adenosine, which in turn activates receptors on macrophages and neutrophils to decrease the release of proinflammatory cytokines (eg, tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-α and interleukin [IL]-6) and elevate the secretion of anti-inflammatory molecules (eg, IL-10).1

Current guidelines recommend initially treating early RA (ie, <6 months) and established RA with DMARDs.2–4 Although MTX is the initial drug of choice for most patients with RA, this medication is contraindicated for some individuals (Table 1).5 Moreover, certain patient characteristics may prompt initial use of other DMARDs or biologic agents rather than MTX. These characteristics include prognostic markers for severe disease, extra-articular manifestations of RA, and comorbid conditions. Biomarkers associated with more severe RA include rheumatoid factor and anticitrullinated protein antibodies as well as upregulated acute-phase reactants, particularly C-reactive protein. In addition, functional limitations, extra-articular organ involvement (eg, skin, eye, lung, heart, renal system, nervous system, or gastrointestinal system) and the presence of radiographic joint erosions are indicative of poor prognosis.6,7 Interestingly, several factors predict that MTX monotherapy will manage clinical symptoms and slow radiographic progression, such as male gender, low disease activity, low level of matrix metalloproteinase 3, and lack of prior DMARD use.8,9

| Table 1 Patient characteristics that contraindicate prescription of MTX5 Note: © Copyright CLINICAL AND EXPERIMENTAL RHEUMATOLOGY 2004. Reproduced from Rau R, Herborn G. Benefit and risk of methotrexate treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2004;22(5 Suppl 35):S83–S94.5 Abbreviation: MTX, methotrexate. |

Although treatment guidelines clearly support the use of MTX in patients with RA, MTX use has evolved and providers need updated practical information on drug delivery. This review updates practitioners on the evolution of MTX treatment, suggests a paradigm shift in MTX employment, and provides pathways for more effective MTX usage.

Evolution of MTX treatment

Rheumatologists have been using MTX since the 1980s when it began to supplant older treatments, such as penicillamine, sulfasalazine, and gold injections.10 Interestingly, MTX was used cautiously in patients with RA after it had come off patent for cancer treatment, even before it received US Food and Drug Administration approval for this indication.10 Notably, MTX was an inexpensive oral tablet and generated little interest for funding of clinical trials. As a result, optimal dosing for MTX in RA was not established and low doses were generally delivered due to concerns about adverse events observed in patients receiving the drug for cancer treatment.10 Several studies carried out in the mid-1980s demonstrated the efficacy of MTX in RA, but it was larger clinical trials in which MTX was compared with biologics that highlighted the effectiveness of the drug.10 Results from these studies also suggested that MTX may be underdosed.11 In addition, analysis of treatment patterns carried out since the advent of biologics has shown that patients initially treated with MTX often prematurely switch to a biologic medication or have a biologic added to their treatment regimen.12 Since the introduction of TNF inhibitors in the late 1990s, there has been a gradual change in how MTX is used in clinical practice, with less aggressive dosing, shorter duration of use, and more rapid escalation to biologics.11–18 For patients starting treatment with a TNF inhibitor, concomitant use of MTX is also declining.12,16 The results of surveys and claims analyses have shown that MTX is administered orally in ~95% of patients and that the maximum dosage usually is 15 mg/wk.12,14 Switching from oral MTX or addition of a biologic occurs within 6 months of MTX initiation in 51% of patients and within the first month for 25%.12 Another claims analysis indicated increased administration of biologics as initial treatment for RA (27% of patients in 2009 and 36% in 2012) and reduced use of MTX along with biologic therapy (91% in 2009 vs 79% in 2012).16 Analysis of RA-related claims from 2008 to 2010 indicated that only 1–15% of patients receiving nonbiologic monotherapy were switched to a biologic during 1 year of follow-up.19,20 This percentage is much smaller than that for patients who initiated treatment with MTX in 2009 or 2012.12,16 Results from a recent survey carried out in Italy, which included information from 1,336 RA patients, indicated that <40% had started treatment with MTX within 3–6 months from the diagnosis.21 This survey also indicated that only 15.5% of patients being treated with MTX were receiving adequate doses (≥15 mg for oral administration and >12 mg for the parenteral delivery).22

The declining use of MTX may be attributed, in part, to the perception that biologic agents are more precisely targeted to molecules and pathways involved in RA. However, the results of several studies indicate that MTX interferes with multiple inflammatory pathways thought to contribute to RA. MTX undergoes polyglutamation within cells, and MTX and its polyglutamates (MTX-PGs) inhibit purine and pyrimidine synthesis, reduce antigen-dependent T-cell proliferation, and promote release of adenosine, which also has anti-inflammatory activity.23 The adenosine 2A receptor is expressed on many immune cells, including neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, T cells, and natural killer cells. Activation of this receptor increases adenylyl cyclase activity, elevates intracellular levels of cAMP, and inhibits proinflammatory nuclear factor κB and JAK/STAT signaling pathways. These intracellular events serve to decrease proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6, and increase the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10.23,24 Given our increasing understanding of the clinical benefits of MTX and its multiple anti-inflammatory actions, it is surprising that use of this DMARD is declining and that patients are being transitioned from MTX after a shorter period than is recommended.25,26

Shifting the paradigm for MTX treatment

MTX provides long-term clinical benefit for patients with RA

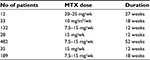

Clinical studies and meta-analyses have demonstrated that patients with RA achieve long-term clinical and structural benefits from MTX. Meta-analysis of results from 7 clinical trials (732 patients, treatment duration 12–52 weeks, and MTX dosage 7.5–25 mg/wk; Table 2) in which MTX was compared with placebo indicated that MTX monotherapy produced clinically important and significant improvements in the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 50 response rate.27 Radiographic progression, represented by an increase in erosion of >3 units on a scale from 0 to 448, was significantly lower for patients who received MTX versus placebo. In contrast, total Sharp scores were similar for MTX and placebo groups. This meta-analysis also indicated that patients who received MTX monotherapy were twice as likely to discontinue treatment because of adverse events (MTX group, 16%; placebo group, 8%). However, there were no significant differences in the frequency of serious adverse events between the MTX and placebo groups. By 52 weeks, more patients in the MTX group had improved by >20% on the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36 physical component.27

| Table 2 MTX dosing in 7 studies included in a meta-analysis of efficacy Note: Data from Lopez-Olivo et al.27 Abbreviation: MTX, methotrexate. |

In another meta-analysis, oral MTX monotherapy was compared with MTX in combination with a biologic agent or with additional synthetic DMARDs.28 The analysis included results from 158 clinical trials and more than 37,000 patients. MTX was administered at dosages >15 mg/wk in 35% of trials (18,537 patients). Twenty-nine of these studies included results for a total of 10,697 MTX-naive patients. Results from this meta-analysis indicated that combinations of MTX with any of several biologic DMARDs (eg, abatacept, adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, rituximab, or tocilizumab) or tofacitinib were statistically superior to oral MTX alone for achievement of ACR50. The estimated probability of ACR50 with combination therapy ranged from 56% to 67%, compared with 41% for MTX monotherapy. Eighteen trials that together included 7,594 patients addressed radiographic progression with oral MTX monotherapy versus combination treatment. Results indicated that MTX plus adalimumab, certolizumab, etanercept, or infliximab was associated with a significant reduction in radiographic progression relative to oral MTX monotherapy. However, effect sizes for all comparisons were small, and the mean difference between MTX monotherapy and combination treatment (2.34 points over 1 year) was less than the minimal clinically important difference of 5 units on the Sharp-van der Heijde scale.28

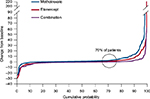

Results from several large-scale clinical trials have shown that approximately one-fifth of patients respond to MTX monotherapy in a manner equivalent to that of patients receiving combination treatment.29–37 Results from the Trial of Etanercept and MTX with Radiographic Patient Outcomes (TEMPO) indicated that ~20% of patients on MTX monotherapy achieved and maintained disease remission for at least 2 years29,30 and that ~70% of patients who received MTX had no radiographic progression during 3 years of follow-up (Figure 1).31 In the Treatment of Early RA (TEAR) trial, 755 participants with early-stage RA associated with poor prognosis were randomized to receive MTX monotherapy or combination treatment (MTX plus etanercept or MTX plus sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine). Participants who received MTX monotherapy were transitioned to combination therapy at 24 weeks if the Disease Activity Score for 28 Joints (DAS28) according to erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was ≥3.2. Of the 370 evaluable participants in the initial MTX monotherapy group, 28% achieved low levels of disease activity and did not require combination treatment. At 102 weeks, the mean DAS28-ESR for these patients was 2.7 versus 2.9 for patients who received combination therapy for the entire treatment period. Patients maintained on MTX monotherapy had less radiographic progression at week 102 than those who received immediate combination therapy (mean Sharp score = 0.2 vs 1.1).32,33 Results from the Swedish Farmacotherapy Trial (SWEFOT) showed that 78% of patients who responded to MTX (DAS28 ≤3.2 at 3–4 months) maintained low disease activity or remission for ≥2 years.34,35 These favorable results with MTX often were obtained in studies in which the oral MTX dosage was not titrated to the level recommended in current guidelines and the patients had not been switched to subcutaneous MTX from orally administered drug when it did not achieve criterion treatment outcomes.36,37

| Figure 1 Results from the TEMPO trial at 3 years of follow-up: probability plots of changes in total Sharp scores. Note: Republished with permission of John Wiley and Sons Inc from van der Heijde D, Klareskog L, Landewé R, et al. Disease remission and sustained halting of radiographic progression with combination etanercept and methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(12):3928–3939. © 2007, American College of Rheumatology permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.31 |

Rescuing patients for whom oral MTX monotherapy fails

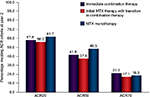

A concern when initiating treatment with MTX monotherapy versus a more intensive combination regimen is whether patients who do not respond to monotherapy will suffer irreversible damage. However, this does not appear to be the case. Results from the TEAR trial indicated that patients initially randomized to receive MTX monotherapy who required transition to combination therapy at 24 weeks (72%) demonstrated DAS28-ESR values (3.5 vs 3.2 at week 48), ACR20/50/70 responses (Figure 2), and radiographic progression (ie, a change in modified Sharp score; 1.2 vs 1.1 at week 102) similar to those for patients who were initially randomized to receive combination therapy or who could be managed with MTX alone.33 In contrast, results from the HOPEFUL 1 trial (ie, Adalimumab, a Human anti-TNF Monoclonal Antibody, Outcome Study for the Persistent Efficacy Under Allocation to Treatment Strategies in Early RA), in which 333 MTX-naive patients received adalimumab plus MTX for 52 weeks or MTX monotherapy for 26 weeks followed by 26 weeks of combination treatment, indicated greater radiographic progression among patients whose treatment was escalated to combination therapy (change in total Sharp score over 52 weeks, 3.30 vs 2.56 points).35 This difference may relate to the fact that, in the HOPEFUL 1 study, the maximum permitted MTX dosage was 8 mg/wk.38 Thus, patients who do not respond to MTX initially and undergo escalation of treatment are able to “catch up” to those who started on a more intensive treatment regimen. It is also worth noting that when used for >1 year, MTX decreases mortality by 70% among patients with RA, even among those who ultimately switch to another therapy.39

| Figure 2 Percentages of patients who achieved a response according to ACR20/50/70 criteria after 2 years of treatment in the TEAR trial. Notes: Patients received immediate combination therapy, initial MTX therapy with transition to combination therapy, or MTX monotherapy. There were no statistically significant differences among groups. Republished with permission of John Wiley and Sons Inc., from O’Dell JR, Curtis JR, Mikuls TR, et al. Validation of the methotrexate-first strategy in patients with early, poor-prognosis rheumatoid arthritis: results from a two-year randomized, double-blind trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(8):1985–1994.© 2013, American College of Rheumatology, permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.33 Abbreviation: ACR, American College of Rheumatology; MTX, methotrexate. |

Pathways for optimizing MTX treatment

Dosage recommendations for oral MTX

The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommends a maximum MTX dosage of 20–30 mg/wk but provides no recommendations for titration.3 Spanish guidelines for the treatment of RA recommend an initial dosage of at least 10 mg/wk. For patients with inadequate responses to this regimen, Spanish guidelines specify rapid escalation to 15–20 mg/wk or even 25 mg/wk, over ~8 weeks, with increments of 2.5–5 mg.40 ACR guidelines for RA treatment provide no dosage recommendations for MTX.2 Results from a systematic review indicated better clinical efficacy when oral MTX was started at 15 mg/wk and escalated at 5 mg/mo to 25–30 mg/wk, which is regarded as the highest tolerable dosage.41 However, the review showed substantial overlap in results for higher and lower MTX dosages. A more recent study indicated that it may not be possible to define the lowest effective dosage for oral MTX in patients with RA.42 This may be attributable to the highly variable absorption of oral MTX. Results from a study in which 41 patients with RA received the same dosage of MTX intravenously and orally indicated that oral bioavailability ranged from ~20%–>100%.43 This variability can be ascribed, at least in part, to polymorphisms in the gene SC19A1, which encodes a reduced folate transporter (RFC) that mediates movement of MTX from the intestine into the bloodstream.44,45

The EULAR guidelines recommend administration of folic or folinic acid for patients who receive MTX.3 Folic or folinic acid can significantly reduce the incidence of gastrointestinal side effects and hepatic dysfunction (determined by measuring serum transaminase levels) and reduces the likelihood that patients will discontinue MTX treatment for any reason.46 Whittle and Hughes suggest that folic or folinic acid be administered the day after MTX to avoid competition between folate and MTX for transport from the intestine to the bloodstream.47 Simultaneous administration of folic acid and MTX significantly decreases the clinical efficacy of MTX, as reflected by Ritchie Index scores, patients’ reports, and physician’s global assessments.48

Can we be more aggressive with dosing oral MTX?

Some evidence supports a clinical benefit associated with delivery of higher dosages of oral MTX for patients with RA. This potential benefit must be weighed against the possibility of dosage-related adverse events with MTX. Results from several clinical trials have indicated that adverse events with oral MTX are not related to dosage. In a study of 147 patients with RA, oral MTX was initiated at ≤15 or 25 mg/wk, and the higher dosage was not associated with a greater frequency of clinical adverse events or laboratory abnormalities.49 Results from a retrospective review of 969 patients with RA who received conventional DMARDs indicated that those who received <10 mg/wk of MTX had a greater frequency of adverse events than those treated with higher dosages.50 A randomized, double-blind, parallel, single-site, pilot trial that compared 2 starting dosages of MTX (15 and 25 mg/wk) in MTX-naive adults with RA indicated no difference in tolerability.51

The recommended minimum duration of MTX monotherapy after which response to treatment can be assessed is 9–12 months for patients with polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (pJIA).52,53 For patients with RA, the minimum recommended duration of MTX treatment for determination of a clinical response is 6 months (or 3 months if no improvement is observed).3 For RA, these minimums are consistent with clinical trial results, indicating continued improvement in symptoms throughout this period.54 In practice, >50% of adults with RA are switched from MTX in <6 months, and 25% are transitioned in the first month.12 These results suggest that physicians can be more aggressive with the MTX dosage and that initial treatment with MTX should be extended to determine the true response to this therapy.

Options for patients who are not effectively treated with oral MTX

Results from large-scale clinical studies indicate that 70%–80% of patients treated with oral MTX monotherapy do not achieve low disease activity.29,32 There are 4 options when oral MTX monotherapy fails to produce desired treatment results: 1) switching from oral to subcutaneous MTX administration,40,55 2) adding other conventional DMARDs (eg, hydroxychloroquine, leflunomide, or sulfasalazine),2 3) adding or switching to a biologic agent,2 or 4) adding or switching to tofacitinib.2 There is significant clinical support for all 4 treatment-advancing approaches in patients whose response to oral MTX monotherapy is inadequate.

Switching to subcutaneous MTX

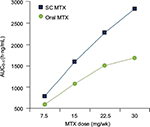

Results from multiple studies have indicated that switching to subcutaneous MTX significantly improves efficacy for patients in whom oral MTX was inadequate (Figure 3).56–58 This benefit likely relates to the higher blood levels of the parent drug (Figure 4) and of long-chain MTX-PGs produced by subcutaneous administration.59,60 Higher blood levels of MTX are achieved from subcutaneous delivery because saturable RFC, expressed by intestinal epithelial cells, is bypassed.23 Blood levels of MTX and of long-chain MTX-PGs correlate significantly with clinical efficacy among patients with RA who receive MTX.60–62 When treatment with oral MTX fails, patients are rarely switched to subcutaneous administration. However, O’Dell et al12 found that 1,808 of 2,511 patients (72%) who were transitioned from oral to subcutaneous MTX were maintained on this treatment for at least 5 years. Results from studies concerned with switching from oral to subcutaneous MTX have been recently reviewed by Yadlapati and Efthimiou.63

| Figure 3 Results of a retrospective analysis of 103 patients with RA. Notes: Significant improvement in disease control was observed following transition from oral to subcutaneous MTX (40 patients were switched because of inadequate efficacy; 63 were switched because of gastrointestinal side effects). Republished with permission of John Wiley and Sons Inc., from Hameed B, Jones H. Subcutaneous methotrexate is well tolerated and superior to oral methotrexate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2010;13(4):e83–e84.© 2010 Asia Pacific League of Associations for Rheumatology and Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd, permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.56 Abbreviations: RA, rheumatoid arthritis; MTX, methotrexate; DAS28, Disease Activity Score for 28 Joints. |

| Figure 4 Results from a single-center, open-label, randomized, 2-period, 2-sequence, single-dose, crossover study in 4 dose groups (7.5, 15, 22.5, and 30 mg) with 54 healthy adults treated with oral and subcutaneous MTX. Note: © 2014 Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. Reproduced from Pichlmeier U, Heuer KU. Subcutaneous administration of methotrexate with a prefilled autoinjector pen results in a higher relative bioavailability compared with oral administration of methotrexate. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014;32(4):563–571.59 Abbreviations: MTX, methotrexate; SC, subcutaneous; AUC, area under the curve. |

Adding other conventional DMARDs or biologics to MTX

Although supplementation of an oral MTX regimen with 1 or more conventional DMARDs can improve treatment efficacy,32,64–66 results from a meta-analysis indicated that such supplementation may not decrease the likelihood of treatment failure resulting from inadequate efficacy.65 Many clinical trials have demonstrated that adding or switching to a biologic improves treatment efficacy in patients who have not responded to treatment with oral MTX.66–68 Adding a biologic or synthetic DMARD to oral MTX is known to improve outcomes for patients who do not respond adequately to oral MTX alone; however, it is less clear whether either of these treatments is superior to the other. Results from the TEAR trial indicated no significant differences between adding etanercept and adding sulfasalazine plus hydroxychloroquine to an oral MTX regimen among patients for whom oral MTX monotherapy had failed.29 Similar results were reported in the RA: Comparison of Active Therapies in Patients with Active Disease Despite MTX Therapy (RACAT) trial,64 and in the SWEFOT, which entailed comparing the addition of infliximab versus the sulfasalazine-hydroxychloroquine combination in patients who did not respond to oral MTX alone.35 In contrast, results from Asia-Pacific Study in Patients to Be Treated with Etanercept or an Alternative Listed DMARD (APPEAL) and Latin RA studies indicated that adding etanercept to oral MTX was significantly superior to adding single-agent hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine, or leflunomide for achieving remission or low disease activity according to DAS28-ESR.69

Switching to biologic monotherapy in a patient not effectively managed with oral MTX is also a viable treatment alternative. Clinical trial results addressing this approach have recently been summarized in a meta-analysis that included results from 41 randomized clinical trials and 14,049 patients. Results from this analysis indicated that biologic monotherapy significantly improved achievement of ACR50 achievement, function, and remission rates versus placebo or continued treatment or continued MTX/other DMARDs.70

Adding or switching to tofacitinib

A meta-analysis of clinical trials indicated that adding tofacitinib significantly improves clinical outcomes for patients with RA whose response to oral MTX monotherapy is inadequate.71 Tofacitinib monotherapy is also effective for patients with inadequate responses to oral MTX.72 Results from a post hoc analysis of clinical trials indicated that the clinical efficacy of tofacitinib monotherapy is similar to that of combination treatment in patients with inadequate responses to conventional DMARDs, including oral MTX.73

Managing intolerance to oral MTX and improving adherence to therapy

Discontinuation of oral MTX is common. In a retrospective review of 762 patients with RA who were receiving oral MTX, the treatment was discontinued by 260 patients (34%) because of adverse events, including gastrointestinal concerns.74 There are several potential approaches to managing adverse events associated with oral MTX: 1) changing the route of MTX administration, 2) reducing the MTX dosage, 3) switching to other conventional DMARDs, and 4) switching to a biologic agent.

Switching to subcutaneous MTX

Switching from oral to subcutaneous administration of MTX has been shown to significantly decrease the frequency of adverse gastrointestinal events in patients with RA.75,76 As mentioned previously, switching from oral to subcutaneous MTX is also associated with improved efficacy.56–58,75

Reducing the MTX dosage

Although reducing the dosage has been proposed as a means to mitigate the adverse effects of oral MTX therapy,5 this approach has 2 important limitations. First, there is no compelling evidence that the adverse events associated with oral MTX are linked to dosage.49,51,77 Second, there is a relationship, albeit weak, between oral MTX dosage and clinical response. Therefore, decreasing the dosage has the potential to negatively impact efficacy.41,78

The risks and benefits of tapering oral MTX treatment for patients with RA have not been well characterized, especially for those who experience adverse events. Three studies that addressed tapering MTX from once weekly to every other week in patients with well-controlled RA indicated that the risk of flares increased following tapering.79–81 In 3 other studies, patients for whom MTX provided good control of RA discontinued treatment, which resulted in increased flare rates.82–84

Switching to other conventional DMARDs

Several other conventional DMARDs appear to be less effective than oral MTX, thereby invalidating a switch in treatments.5 The long-term radiologic outcomes achieved with oral MTX are superior to those for sulfasalazine,85 and the results of a small-scale clinical trial demonstrated significant clinical superiority of MTX over hydroxychloroquine for patients with RA.86 In contrast, leflunomide and MTX had similar efficacy in 2 clinical studies.87,88

Switching to a biologic agent

The efficacy of most biologic agents is enhanced when the agent is administered in combination with MTX, and this benefit, at least for some agents, is dosage related.67,89 Therefore, switching from oral MTX to a biologic may be impractical. Moreover, there appears to be no correlation between MTX dosage and toxicity when MTX is combined with a biologic agent.90 The IL-6 inhibitor tocilizumab is equally effective when delivered as monotherapy or with MTX in patients whose response to MTX alone was inadequate.91 This may also be true for tofacitinib.73

Improving patient adherence to MTX treatment

Patients with RA are poorly adherent to MTX treatment

Adherence to oral MTX treatment is often poor. In a study of 251 patients, 105 patients (42%) reported not taking MTX as prescribed.92 Reasons for nonadherence in that study included forgetting to take the drug (33%), not needing it when feeling well (24%), and concern about long-term safety (24%). Among the nonadherent patients, 53% took lower doses, 52% skipped doses, and 6% reported other nonprescribed ways of taking MTX.92 A study of 6,018 patients for whom DMARDs had been recently prescribed indicated that ~50% of the patients prescribed MTX had stopped this treatment within 1 year; the median time before stopping DMARD therapy was 150 days.93 Similarly, results from a claims analysis of 24,479 patients who underwent MTX treatment indicated that ~50% discontinued it within 1 year.14

Poor adherence to treatment among patients with RA is not unique to MTX. Results from an analysis of the Tennessee Medicaid databases (1995–2004) that included information for 14,932 patients with RA indicated that persistence with therapy was similar with all nonbiologic DMARDs except sulfasalazine, which had lower persistence.93 In addition, persistence with MTX was similar to that recorded for etanercept and adalimumab and was better than that for infliximab.93

How can we improve patient adherence to MTX?

Results from several studies have indicated that education and counseling significantly improve adherence to therapy for patients with RA who receive conventional DMARDs, including MTX.94–96 Furthermore, subcutaneous MTX is associated with better treatment persistence than oral MTX. Results from the Canadian Early Arthritis Cohort (CATCH) study, which included 666 patients on MTX treatment (417 oral and 249 subcutaneous) indicated that at 1 year, 49% of the patients initially treated with subcutaneous MTX had changed treatment versus 77% of those initially treated with oral MTX.97 A retrospective review of the patients who were switched from oral to subcutaneous MTX and had follow-up for 5 years indicated that 50% persisted with subcutaneous treatment for at least 51 months.98

Dosing MTX

Oral administration

It has been suggested that oral MTX should be started at 10–15 mg/wk, with gradual escalation by 5 mg every 2–4 weeks to a dosage of 20–30 mg/wk.41 However, Medley et al49 suggest that initiation of oral MTX at 25 mg/wk does not pose greater risk of liver toxicity or other adverse effects versus gradual titration from a low dosage.

Treatment of patients with pJIA may provide important information about MTX dose setting for adults with RA. The recommended starting MTX dosage for children with pJIA is 10–15 mg/m2/wk, which converts to ~0.3–0.6 mg/kg/wk.99,100 The corresponding weight-based dose for a 70 kg adult with RA is 0.2 mg/kg (15 mg/wk). This is about one-half the dose administered to patients with pJIA. The recommended duration for MTX monotherapy in patients with pJIA is also longer than that typically used for adults with RA.

Dosing recommendations for switching from oral to subcutaneous MTX

Studies have demonstrated that the bioavailability of a dose of MTX delivered subcutaneously is significantly higher than the bioavailability of an equivalent dose administered orally.59,101,102 Therefore, when switching to subcutaneous MTX, the patient should receive the same dose that had been prescribed for oral administration. This will significantly increase MTX exposure.103

Initiating treatment with subcutaneous MTX

While patients typically prefer oral versus injected treatment,104 initiating treatment with subcutaneous MTX versus oral drug is a potentially better option for patients willing to undertake injections. A head-to-head comparison of oral versus subcutaneous MTX in patients with RA indicated significant superiority of subcutaneously administered drug for achievement of ACR20 and ACR70 improvements.105 Results from the CATCH study also demonstrated better clinical efficacy and better persistence with subcutaneous MTX versus oral drug,97 and that treatment with subcutaneous MTX delays progression to a biologic agent versus oral drug.106 All of these results support the view that initiating treatment with subcutaneous MTX has the potential to provide superior clinical outcomes versus oral drug and delay progression to more expensive biologic therapies.

Dosing MTX when combined with a TNF inhibitor

Supplementing MTX treatment with a TNF inhibitor is more effective than switching to TNF inhibitor monotherapy; however, guidance is lacking for MTX dosing in this setting. A post hoc analysis of results from the TEMPO and Combination of MTX and Etanercept in Active Early RA (COMET) trials, in which patients were grouped according to the MTX dosage administered in combination with etanercept (<10.0, 10.0–17.5, or >17.5 mg/wk), indicated no differences among the study groups for numerous metrics: achievement of DAS28 remission or low disease activity (Figure 5), ACR20/50/70 responses, Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index scores, or quality of life.107 In contrast, patients with early-stage RA who were treated with combination therapy in the CONCERTO trial (ie, Study to Determine the Effects of Different Doses of MTX When Taken with Adalimumab in Subjects with Early RA) had better clinical outcomes with a high MTX dosage plus adalimumab if they had not received MTX previously.89 Neither of these studies directly addressed whether the MTX dose could be reduced upon adding a TNF inhibitor, without compromising treatment efficacy. The Dutch RA Monitoring (DREAM) registry included information of 458 patients (34%) who underwent tapering of MTX, 126 patients (10%) who discontinued MTX, and 747 patients (56%) who maintained their MTX dosage after adding a TNF inhibitor for the first time. This registry showed no differences in DAS28 results for the 3 groups during 24 months of follow-up.108 Similarly, results from the Infliximab RA MTX Tapering (iRAMT) trial indicated that reducing the MTX dosage after adding infliximab did not adversely affect the outcomes for ~75% of patients.109

| Figure 5 Percentage of patients achieving (A) DAS28 remission and (B) DAS28 low disease activity at baseline and at 6, 12, and 24 months. Note: DAS28 remission was defined as DAS28 <2.6; low disease activity was defined as DAS28 >2.6 and <3.2. Reproduced from Gallo G, Brock F, Kerkmann U, Kola B, Huizinga TW. Efficacy of etanercept in combination with methotrexate in moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis is not dependent on methotrexate dosage. RMD Open. 2016;2(1):e000186. Copyright © 2016 with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.107 Abbreviations: DAS28, Disease Activity Score for 28 Joints; ETN, etanercept; MTX, methotrexate. |

Summary recommendations for MTX optimization

This review supports several recommendations for optimizing MTX therapy for patients with RA:

Administration of a high initial dose of MTX followed by rapid titration can improve the response to oral MTX and does not appear to compromise safety or tolerability.

Treatment with oral MTX, with appropriate dose titration, should be continued for at least 6 months to accurately assess clinical response (if the patient has experienced any response to treatment by 3 months).

Patients for whom MTX treatment fails because of intolerability or inadequate efficacy may be “rescued” by switching to subcutaneous MTX.

Consideration should also be given to starting with subcutaneous MTX given its favorable bioavailability and pharmacodynamic profile.

Starting patients on subcutaneous MTX or switching from oral to subcutaneous delivery is likely to improve treatment persistence.

If a patient is switched from oral to subcutaneous MTX, a concomitant dosage increase should be avoided. After the change in delivery route, the dose may be titrated as needed.

If a patient has tolerated MTX monotherapy but has not responded adequately, the patient may also be prescribed another agent. In such cases, the MTX dosage and route of administration used before treatment augmentation should be maintained, with titration as needed.

Acknowledgments

This study and development of the manuscript was supported by Medac Pharma, Inc. The authors acknowledge the support of Robert W. Rhoades, PhD, in the development of the manuscript.

Disclosure

Alfonso Bello served as a speaker for Abbvie, speaker and advisory board for Pfizer and Medac Pharma, and consultant and speaker for Horizon Pharma and Mallinckrodt. Elizabeth Perkins served as a consultant for Medac Pharma, Pfizer Inc, Lilly, USA, LLC, Amgen Inc, and Antares Pharma Inc. Randy Jay served as a consultant for Medac Pharma. Petros Efthimiou served as a speaker and consultant for Medac Pharma. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Chan ES, Cronstein BN. Molecular action of methotrexate in inflammatory diseases. Arthritis Res. 2002;4(4):266–273. | ||

Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL Jr, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(1):1–26. | ||

Smolen JS, Landewé R, Breedveld FC, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2013 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(3):492–509. | ||

Todoerti M, Maglione W, Bernero E, et al. Systematic review of 2008-2012 literature and update of recommendations for the use of methotrexate in rheumatic diseases, with a focus on rheumatoid arthritis. Reumatismo. 2013;65(5):207–218. | ||

Rau R, Herborn G. Benefit and risk of methotrexate treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2004;22(5 suppl 35):S83–S94. | ||

Verstappen SM, Lunt M, Bunn DK, Scott DG, Symmons DP. In patients with early inflammatory polyarthritis, ACPA positivity, younger age and inefficacy of the first non-biological DMARD are predictors for receiving biological therapy: results from the Norfolk Arthritis Register. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(8):1428–1432. | ||

Davis JM 3rd, Knutson KL, Skinner JA, et al. A profile of immune response to herpesvirus is associated with radiographic joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14(1):R24. | ||

Drouin J, Haraoui B; 3e Initiative Group. Predictors of clinical response and radiographic progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with methotrexate monotherapy. J Rheumatol. 2010;37(7):1405–1410. | ||

Shiozawa K, Yamane T, Murata M, et al. MMP-3 as a predictor for structural remission in RA patients treated with MTX monotherapy. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18:55. | ||

Sokka T. Increases in use of methotrexate since the 1980s. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010;28(5 suppl 61):S13–S20. | ||

Pincus T, Gibson KA, Castrejón I. Update on methotrexate as the anchor drug for rheumatoid arthritis. Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 2013;71(Suppl 1):S9–S19. | ||

Rohr MK, Mikuls TR, Cohen SB, Thorne CJ, O’Dell JR. The underuse of methotrexate in the treatment of RA: a national analysis of prescribing practices in the U.S. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). Epub 2016 Nov 18. | ||

Yazici Y, Shi N, John A. Utilization of biologic agents in rheumatoid arthritis in the United States: analysis of prescribing patterns in 16,752 newly diagnosed patients and patients new to biologic therapy. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2008;66(2):77–85. | ||

Curtis JR, Zhang J, Xie F, et al. Use of oral and subcutaneous methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis patients in the United States. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014;66(11):1604–1611. | ||

Detert J, Klaus P. Biologic monotherapy in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Biologics. 2015;9:35–43. | ||

O’Dell JR, Cohen SB, Thorne JC, Mikuls TR. Changing use of methotrexate (MTX) and biologics in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in the United States (US): results of a comprehensive pharmaceutical claims analysis. Presented at: EULAR/Annual European Congress of Rheumatology; June 8–11; 2016; London. | ||

Desai RJ, Solomon DH, Liu J, Kim SC [webpage on the Internet]. Secular trends in use of disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in the United States [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(suppl 10). Available from: http://acrabstracts.org/abstract/secular-trends-in-use-of-disease-modifying-anti-rheumatic-drugs-for-the-treatment-of-rheumatoid-arthritis-in-the-united-states. Accessed October 24, 2016. | ||

Engel-Nitz NM, Ogale S, Kulakodlu M. Use of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: a retrospective study of monotherapy and adherence to combination therapy with non-biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs. Rheumatol Ther. 2015;2(2):127–139. | ||

Desai RJ, Rao JK, Hansen RA, Fang G, Maciejewski ML, Farley JF. Predictors of treatment initiation with tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2014;20(11):1110–1120. | ||

Zhang J, Xie F, Delzell E, et al. Trends in the use of biologic agents among rheumatoid arthritis patients enrolled in the US medicare program. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65(11):1743–1751. | ||

Manara M, Bianchi G, Bruschi E, et al. Adherence to current recommendations on the use of methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis in Italy: results from the MARI study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2016;34(3):473–479. | ||

Idolazzi L, Adami S, Capozza R, et al. Suboptimal methotrexate use in rheumatoid arthritis patients in Italy: the MARI study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33(6):895–899. | ||

Tian H, Cronstein BN. Understanding the mechanisms of action of methotrexate: implications for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2007;65(3):168–173. | ||

Milne GR, Palmer TM. Anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects of the A2A adenosine receptor. ScientificWorldJournal. 2011;11:320–339. | ||

Emery P, Sebba A, Huizinga TW. Biologic and oral disease-modifying antirheumatic drug monotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(12):1897–1904. | ||

Taylor P, van Vollenhoven R, Aletaha D. Optimising patient outcomes throughout the rheumatoid arthritis patient journey: the exception, the standard, and the rule. EMJ Rheumatol. 2016;3:36–47. | ||

Lopez-Olivo MA, Siddhanamatha HR, Shea B, Tugwell P, Wells GA, Suarez-Almazor ME. Methotrexate for treating rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;6:CD000957. | ||

Hazlewood GS, Barnabe C, Tomlinson G, Marshall D, Devoe D, Bombardier C. Methotrexate monotherapy and methotrexate combination therapy with traditional and biologic disease modifying antirheumatic drugs for rheumatoid arthritis: abridged Cochrane Systematic Review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2016;353:i1777. | ||

Klareskog L, van der Heijde D, de Jager JP, et al. Therapeutic effect of the combination of etanercept and methotrexate compared with each treatment alone in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363(9410):675–681. | ||

van der Heijde D, Klareskog L, Rodriguez-Valverde V, et al. Comparison of etanercept and methotrexate, alone and combined, in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: two-year clinical and radiographic results from the TEMPO study, a double-blind, randomized trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(4):1063–1074. | ||

van der Heijde D, Klareskog L, Landewé R, et al. Disease remission and sustained halting of radiographic progression with combination etanercept and methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(12):3928–3939. | ||

Moreland LW, O’Dell JR, Paulus HE, et al. A randomized comparative effectiveness study of oral triple therapy versus etanercept plus methotrexate in early aggressive rheumatoid arthritis: the treatment of Early Aggressive Rheumatoid Arthritis Trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(9):2824–2835. | ||

O’Dell JR, Curtis JR, Mikuls TR, et al. Validation of the methotrexate-first strategy in patients with early, poor-prognosis rheumatoid arthritis: results from a two-year randomized, double-blind trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(8):1985–1994. | ||

van Vollenhoven RF, Ernestam S, Geborek P, et al. Addition of infliximab compared with addition of sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine to methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis (Swefot trial): 1-year results of a randomised trial. Lancet. 2009;374(9688):459–466. | ||

van Vollenhoven RF, Geborek P, Forslind K, et al. Conventional combination treatment versus biological treatment in methotrexate-refractory early rheumatoid arthritis: 2 year follow-up of the randomised, non-blinded, parallel-group Swefot trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9827):1712–1720. | ||

Pincus T, Furer V, Sokka T. Underestimation of the efficacy, effectiveness, tolerability, and safety of weekly low-dose methotrexate in information presented to physicians and patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010;28(5 suppl 61):S68–S79. | ||

Durán J, Bockorny M, Dalal D, LaValley M, Felson DT. Methotrexate dosage as a source of bias in biological trials in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(9):1595–1598. | ||

Yamanaka H, Ishiguro N, Takeuchi T, et al. Recovery of clinical but not radiographic outcomes by the delayed addition of adalimumab to methotrexate-treated Japanese patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: 52-week results of the HOPEFUL-1 trial. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53(5):904–913. | ||

Wasko MC, Dasgupta A, Hubert H, Fries JF, Ward MM. Propensity-adjusted association of methotrexate with overall survival in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(2):334–342. | ||

Tornero Molina J, Ballina García FJ, Calvo Alén J, et al. Recommendations for the use of methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis: up and down scaling of the dose and administration routes. Reumatol Clin. 2015;11(1):3–8. | ||

Visser K, van der Heijde D. Optimal dosage and route of administration of methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(7):1094–1099. | ||

Nair SC, Jacobs JW, Bakker MF, et al. Determining the lowest optimally effective methotrexate dose for individual RA patients using their dose response relation in a tight control treatment approach. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0148791. | ||

Herman RA, Veng-Pedersen P, Hoffman J, Koehnke R, Furst DE. Pharmacokinetics of low-dose methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis patients. J Pharm Sci. 1989;78(2):165–171. | ||

Yee SW, Gong L, Badagnani I, Giacomini KM, Klein TE, Altman RB. SLC19A1 pharmacogenomics summary. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2010;20(11):708–715. | ||

Laverdière C, Chiasson S, Costea I, Moghrabi A, Krajinovic M. Polymorphism G80A in the reduced folate carrier gene and its relationship to methotrexate plasma levels and outcome of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2002;100(10):3832–3834. | ||

Shea B, Swinden MV, Tanjong Ghogomu E, et al. Folic acid and folinic acid for reducing side effects in patients receiving methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;5:CD000951. | ||

Whittle SL, Hughes RA. Folate supplementation and methotrexate treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: a review. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43(3):267–271. | ||

Griffith SM, Fisher J, Clarke S, et al. Do patients with rheumatoid arthritis established on methotrexate and folic acid 5 mg daily need to continue folic acid supplements long term? Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000;39(10):1102–1109. | ||

Medley S, Dolan AL, Coakley G. How safe is starting high dose methotrexate? Presented at EULAR/Annual European Congress of Rheumatology. June 10–13, 2009; Copenhagen Denmark. Abstract SAT0150. | ||

Lampropoulos CE, Orfanos P, Bournia VK, et al. Adverse events and infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with conventional drugs or biologic agents: a real world study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33(2):216–224. | ||

Hobl EL, Mader RM, Jilma B, et al. A randomized, double-blind, parallel, single-site pilot trial to compare two different starting doses of methotrexate in methotrexate-naïve adult patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Ther. 2012;34(5):1195–1203. | ||

Ruperto N, Murray KJ, Gerloni V, et al. A randomized trial of parenteral methotrexate comparing an intermediate dose with a higher dose in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis who failed to respond to standard doses of methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(7):2191–2201. | ||

Ringold S, Weiss PF, Colbert RA, et al. Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance consensus treatment plans for new-onset polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014;66(7):1063–1072. | ||

Soubrier M, Puéchal X, Sibilia J, et al. Evaluation of two strategies (initial methotrexate monotherapy vs its combination with adalimumab) in management of early active rheumatoid arthritis: data from the GUEPARD trial. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48(11):1429–1434. | ||

Bykerk VP, Akhavan P, Hazlewood GS, et al. Canadian Rheumatology Association recommendations for pharmacological management of rheumatoid arthritis with traditional and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. J Rheumatol. 2012;39(8):1559–1582. | ||

Hameed B, Jones H. Subcutaneous methotrexate is well tolerated and superior to oral methotrexate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2010;13(4):e83–e84. | ||

Bianchi G, Caporali R, Todoerti M, Mattana P. Methotrexate and rheumatoid arthritis: current evidence regarding subcutaneous versus oral routes of administration. Adv Ther. 2016;33(3):369–378. | ||

Branco JC, Barcelos A, de Araújo FP, et al. Utilization of subcutaneous methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis patients after failure or intolerance to oral methotrexate: a Multicenter Cohort Study. Adv Ther. 2016;33(1):46–57. | ||

Pichlmeier U, Heuer KU. Subcutaneous administration of methotrexate with a prefilled autoinjector pen results in a higher relative bioavailability compared with oral administration of methotrexate. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014;32(4):563–571. | ||

Dervieux T, Zablocki R, Kremer J. Red blood cell methotrexate polyglutamates emerge as a function of dosage intensity and route of administration during pulse methotrexate therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49(12):2337–2345. | ||

Hornung N, Ellingsen T, Attermann J, Stengaard-Pedersen K, Poulsen JH. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with methotrexate (MTX): concentrations of steady-state erythrocyte MTX correlate to plasma concentrations and clinical efficacy. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(9):1709–1715. | ||

Dervieux T, Furst D, Lein DO, et al. Polyglutamation of methotrexate with common polymorphisms in reduced folate carrier, aminoimidazole carboxamide ribonucleotide transformylase, and thymidylate synthase are associated with methotrexate effects in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(9):2766–2774. | ||

Yadlapati S, Efthimiou P. Inadequate response or intolerability to oral methotrexate: is it optimal to switch to subcutaneous methotrexate prior to considering therapy with biologics? Rheumatol Int. 2016;36(5):627–633. | ||

O’Dell JR, Mikuls TR, Taylor TH, et al. Therapies for active rheumatoid arthritis after methotrexate failure. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(4):307–318. | ||

Katchamart W, Trudeau J, Phumethum V, Bombardier C. Methotrexate monotherapy versus methotrexate combination therapy with non-biologic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs for rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;4:CD008495. | ||

Karlsson JA, Neovius M, Nilsson JÅ, et al. Addition of infliximab compared with addition of sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine to methotrexate in early rheumatoid arthritis: 2-year quality-of-life results of the randomised, controlled, SWEFOT trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(12):1927–1933. | ||

Buckley F, Finckh A, Huizinga TW, Dejonckheere F, Jansen JP. Comparative efficacy of novel DMARDs as monotherapy and in combination with methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis patients with inadequate response to conventional DMARDs: a network meta-analysis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21:409–423. | ||

Orme ME, Macgilchrist KS, Mitchell S, Spurden D, Bird A. Systematic review and network meta-analysis of combination and monotherapy treatments in disease-modifying antirheumatic drug-experienced patients with rheumatoid arthritis: analysis of American College of Rheumatology criteria scores 20, 50, and 70. Biologics. 2012;6:429–464. | ||

Fleischmann R, Koenig AS, Szumski A, Nab HW, Marshall L, Bananis E. Short-term efficacy of etanercept plus methotrexate vs combinations of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs with methotrexate in established rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53(11):1984–1993. | ||

Singh JA, Hossain A, Tanjong Ghogomu E, Mudano AS, Tugwell P, Wells GA. Biologic or tofacitinib monotherapy for rheumatoid arthritis in people with traditional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) failure: a Cochrane Systematic Review and network meta-analysis (NMA). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11:CD012437. | ||

Berhan A. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of tofacitinib in patients with an inadequate response to disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs: a meta-analysis of randomized double-blind controlled studies. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:332. | ||

Kremer JM, Bloom BJ, Breedveld FC, et al. The safety and efficacy of a JAK inhibitor in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase IIa trial of three dosage levels of CP-690,550 versus placebo. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(7):1895–1905. | ||

Zerbini C, Radominski S, Cardiel MH, et al [webpage on the Internet]. Efficacy and safety of tofacitinib monotherapy versus combination therapy in a Latin American subpopulation of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a pooled phase 3 analysis [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(suppl 10). Available from: http://acrabstracts.org/abstract/efficacy-and-safety-of-tofacitinib-monotherapy-versus-combination-therapy-in-a-latin-american-subpopulation-of-patients-with-rheumatoid-arthritis-a-pooled-phase-3-analysis. Accessed October 24, 2016. | ||

Nikiphorou E, Negoescu A, Fitzpatrick JD, et al. Indispensable or intolerable? Methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis: a retrospective review of discontinuation rates from a large UK cohort. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33(5):609–614. | ||

Li D, Yang Z, Kang P, Xie X. Subcutaneous administration of methotrexate at high doses makes a better performance in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis compared with oral administration of methotrexate: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;45(6):656–662. | ||

Kromann CB, Lage-Hansen PR, Koefoed M, Jemec GB. Does switching from oral to subcutaneous administration of methotrexate influence on patient reported gastro-intestinal adverse effects? J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26(2):188–190. | ||

Verstappen SM, Bakker MF, Heurkens AH, et al. Adverse events and factors associated with toxicity in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis treated with methotrexate tight control therapy: the CAMERA study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(6):1044–1048. | ||

Furst DE, Koehnke R, Burmeister LF, Kohler J, Cargill I. Increasing methotrexate effect with increasing dose in the treatment of resistant rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1989;16(3):313–320. | ||

Tishler M, Caspi D, Yaron M. Methotrexate treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: is a fortnightly maintenance schedule enough? Ann Rheum Dis. 1992;51(12):1330–1331. | ||

Luis M, Pacheco-Tena C, Cazarín-Barrientos J, et al. Comparison of two schedules for administering oral low-dose methotrexate (weekly versus every-other-week) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in remission: a twenty-four week, single blind, randomized study. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(10):2160–2165. | ||

Kremer JM, Davies JM, Rynes RI, et al. Every-other-week methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. A double-blind, placebo-controlled prospective study. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38(5):601–607. | ||

Kremer JM, Rynes RI, Bartholomew LE. Severe flare of rheumatoid arthritis after discontinuation of long-term methotrexate therapy. Double-blind study. Am J Med. 1987;82(4):781–786. | ||

Gøtzsche PC, Hansen M, Stoltenberg M, et al. Randomized, placebo controlled trial of withdrawal of slow-acting antirheumatic drugs and of observer bias in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 1996;25(4):194–199. | ||

ten Wolde S, Breedveld FC, Hermans J, et al. Randomised placebo-controlled study of stopping second-line drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 1996;347(8998):347–352. | ||

Hider SL, Silman A, Bunn D, Manning S, Symmons D, Lunt M. Comparing the long-term clinical outcome of treatment with methotrexate or sulfasalazine prescribed as the first disease-modifying antirheumatic drug in patients with inflammatory polyarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(11):1449–1455. | ||

Alam MK, Sutradhar SR, Pandit H, et al. Comparative study on methotrexate and hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Mymensingh Med J. 2012;21(3):391–398. | ||

Cohen S, Cannon GW, Schiff M, et al. Two-year, blinded, randomized, controlled trial of treatment of active rheumatoid arthritis with leflunomide compared with methotrexate. Utilization of Leflunomide in the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis Trial Investigator Group. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(9):1984–1992. | ||

Tugwell P, Wells G, Strand V, et al. Clinical improvement as reflected in measures of function and health-related quality of life following treatment with leflunomide compared with methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: sensitivity and relative efficiency to detect a treatment effect in a twelve-month, placebo-controlled trial. Leflunomide Rheumatoid Arthritis Investigators Group. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(3):506–514. | ||

Burmester GR, Kivitz AJ, Kupper H, et al. Efficacy and safety of ascending methotrexate dose in combination with adalimumab: the randomised CONCERTO trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(6):1037–1044. | ||

Burmester GR, Kivitz AJ, Van Vollenhoven RF, et al. Methotrexate dose has minimal effects on methotrexate-related toxicity in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis treated in combination with adalimumab – results of Concerto Trial. 2013. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(Suppl 10):2688. Presented at American College of Rheumatology/Association of Rheumatology Health Professionals Annual Meeting; San Diego, CA; October 25–30, 2013. | ||

Bykerk VP, Östör AJ, Alvaro-Gracia J, et al. Comparison of tocilizumab as monotherapy or with add-on disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate responses to previous treatments: an open-label study close to clinical practice. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34(3):563–571. | ||

DiBenedetti DB, Zhou X, Reynolds M, Ogale S, Best JH. Assessing methotrexate adherence in rheumatoid arthritis: a cross-sectional survey. Rheumatol Ther. 2015;2(1):73–84. | ||

Grijalva CG, Chung CP, Arbogast PG, Stein CM, Mitchel EF Jr, Griffin MR. Assessment of adherence to and persistence on disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Med Care. 2007;45(10 suppl 2):S66–S76. | ||

Hill J, Bird H, Johnson S. Effect of patient education on adherence to drug treatment for rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60(9):869–875. | ||

Homer D, Nightingale P, Jobanputra P. Providing patients with information about disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs: individually or in groups? A pilot randomized controlled trial comparing adherence and satisfaction. Musculoskeletal Care. 2009;7(2):78–92. | ||

Evers AW, Kraaimaat FW, van Riel PL, de Jong AJ. Tailored cognitive-behavioral therapy in early rheumatoid arthritis for patients at risk: a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2002;100(1–2):141–153. | ||

Hazlewood GS, Thorne JC, Pope JE, et al. The comparative effectiveness of oral versus subcutaneous methotrexate for the treatment of early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(6):1003–1008. | ||

Scott DG, Claydon P, Ellis C. Retrospective evaluation of continuation rates following a switch to subcutaneous methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis patients failing to respond to or tolerate oral methotrexate: the MENTOR study. Scand J Rheumatol. 2014;43(6):470–476. | ||

Ravelli A, Martini A. Methotrexate in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: answers and questions. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(8):1830–1833. | ||

Ramanan AV, Whitworth P, Baildam EM. Use of methotrexate in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88(3):197–200. | ||

Schiff MH, Jaffe JS, Freundlich B. Head-to-head, randomised, crossover study of oral versus subcutaneous methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: drug-exposure limitations of oral methotrexate at doses ≥15 mg may be overcome with subcutaneous administration. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(8):1549–1551. | ||

Hoekstra M, Haagsma C, Neef C, Proost J, Knuif A, van de Laar M. Bioavailability of higher dose methotrexate comparing oral and subcutaneous administration in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(4):645–648. | ||

Schiff M, Sadowski P [webpage on the Internet]. Oral to subcutaneous methotrexate dose-conversion strategies in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(suppl 10). Available from: http://acrabstracts.org/abstract/oral-to-subcutaneous-methotrexate-dose-conversion-strategies-in-the-treatment-of-rheumatoid-arthritis. Accessed October 24, 2016. | ||

Louder AM, Singh A, Saverno K, et al. Patient preferences regarding rheumatoid arthritis therapies: a conjoint analysis. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2016;9(2):84–93. | ||

Braun J, Kästner P, Flaxenberg P, et al. Comparison of the clinical efficacy and safety of subcutaneous versus oral administration of methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: results of a six-month, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, controlled, phase IV trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):73–81. | ||

Gottheil S, Thorne JC, Schieir O, et al. Early use of subcutaneous MTX monotherapy vs. MTX oral or combination therapy significantly delays time to initiating biologics in early RA. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(suppl 10). Available from: http://acrabstracts.org/abstract/early-use-of-subcutaneous-mtx-monotherapy-vs-mtx-oral-or-combination-therapy-significantly-delays-time-to-initiating-biologics-in-early-ra/. Accessed November 18, 2016. | ||

Gallo G, Brock F, Kerkmann U, Kola B, Huizinga TW. Efficacy of etanercept in combination with methotrexate in moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis is not dependent on methotrexate dosage. RMD Open. 2016;2(1):e000186. | ||

Manders SHM, van de Laar MAFJ, Rongen-van Dartel SAA, et al. Tapering and discontinuation of methotrexate in patients with RA treated with TNF inhibitors: data from the DREAM registry. RMD Open. 2015;1:e000147. | ||

Fleischmann RM, Cohen SB, Moreland LW, et al. Methotrexate dosage reduction in patients with rheumatoid arthritis beginning therapy with infliximab: the Infliximab Rheumatoid Arthritis Methotrexate Tapering (iRAMT) trial. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21(8):1181–1190. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.