Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 15

Psychological Safety and Affective Commitment Among Chinese Hospital Staff: The Mediating Roles of Job Satisfaction and Job Burnout

Authors Li J, Li S, Jing T, Bai M , Zhang Z , Liang H

Received 23 March 2022

Accepted for publication 10 June 2022

Published 23 June 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 1573—1585

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S365311

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Jiahui Li,1 Sisi Li,1 Tiantian Jing,1 Mayangzong Bai,1 Zhiruo Zhang,1 Huigang Liang2

1School of Public Health, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, 200025, People’s Republic of China; 2Department of Business Information & Technology, Fogelman College of Business & Economics, University of Memphis, Memphis, TN, USA

Correspondence: Zhiruo Zhang; Huigang Liang, Tel +86-21-63846590-776145, Email [email protected]; [email protected]

Purpose: The affective commitment of hospital staff is important for human resources management and the sustainable development of hospitals. Psychological safety is an important factor that contributes to an emotional connection to an organization among staff, yet its functional mechanism remains unclear. This study explored how psychological safety influenced affective commitment through the mediating roles of job satisfaction and job burnout.

Methods: A battery of surveys were administered to all medical staff (n = 267) in a local second-grade comprehensive hospital. The surveys included the Psychological Safety Scale, Affective Commitment Scale, Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire, Maslach Burnout Inventory–Human Service Survey, and Perceived Organizational Support Scale.

Results: Job satisfaction and job burnout fully mediated the relationship between psychological safety and affective commitment among hospital staff. In addition, perceived organizational support moderated the mediating path via job burnout, and the indirect effect of job burnout decreased when perceived organizational support increased.

Conclusion: Psychological safety may enhance the affective commitment of hospital staff through improving job satisfaction or reducing job burnout. Perceived organizational support may counteract the deleterious effect of job burnout on affective commitment. Effective strategies to improve affective commitment among hospital staff may require consideration of job burnout and job satisfaction.

Keywords: psychological safety, affective commitment, job burnout, job satisfaction, hospital management

Introduction

Human resources are essential for the survival and sustainable development of modern organizations. Organizational commitment is a crucial factor that drives talents to serve their organizations for the long term. Affective commitment is a form of organizational commitment that refers to employees’ emotional dependence on, identification with, and involvement in an organization.1 Compared with normative commitment and continuous commitment, which are two other forms of organizational commitment, affective commitment reflects a real attitude toward the organization because of its emotional nature.2 Compared with employees with low affective commitment, those with high affective commitment have a strong sense of belonging and low turnover intention and behaviors,2,3 display more willingness to perform organizational citizenship behaviors,4,5 and are more dedicated to making efforts to serve the organization.3

Affective commitment is especially important in medical settings where high knowledge and skills are required. The sense of belonging also boosts resilience among medical staff and improves their overall well-being.6 Affective commitment among medical staff is also important as it can positively predict patient experience, nursing quality, and patient safety culture.4,7 Hospitals usually invest large amounts of resources in training to build professional skills and knowledge among medical staff. As a result, medical staff become more marketable and more committed to the medical profession.8 However, professional commitment does not necessarily equate to organizational commitment.9,10 The disparity between professional commitment and organizational commitment creates a paradox where those who benefit more from training may have a higher possibility of turnover because of high job marketability and low affective commitment.8,11

Previous research showed that the antecedents of affective commitment included transformational leadership, role ambiguity, and individual differences.2 The present investigation focused on psychological safety, which is an affectively sensitive feature of organizational atmosphere. This is also important in the healthcare field as medical staff often work in teams that benefit from a psychologically safe atmosphere. Most previous studies on psychological safety and affective commitment focused on the direct association between the two constructs.12,13 However, the specific underlying mechanism(s) remain unclear. (High) job satisfaction and (low) job burnout are considered critical features associated with affective commitment, especially in medical settings; therefore, this study investigated whether these two features explained the linkage between psychological safety and affective commitment. The hypotheses proposed are as follows.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

From Psychological Safety to Affective Commitment

Affective commitment can be predicted by both personal (such as seniority and education) and organizational (such as organizational culture and leadership integrity) factors.1 Psychological safety is an organizational factor that is defined as a shared belief that it is safe to take interpersonal risks in the organization.14 Previous studies found that employees with high psychological safety felt supported by their organization and were willing to express themselves, which contributed to their commitment.15 A positive association between psychological safety and affective commitment was also found in medical settings.16 Corroborating social exchange processes,17 a psychologically safe atmosphere promotes a flexible working environment characterized by safety, mutual trust, and respect.18 This leads to better performance and pleasant experiences19 and reduces the distress caused by medical errors or adverse patient outcomes (such as anxiety and burnout).20 Conversely, a psychologically unsafe working environment reduces mutual trust and means employees must cope with anxiety and pressure on their own,12 thereby limiting pleasant emotional experiences and compromising affective bonds with the organization. Therefore, we hypothesized that psychological safety would positively contribute to affective commitment (H1).

Job Satisfaction as an Enabling Mediator

Job satisfaction reflects employees’ feelings about their jobs.21 Empirical researches suggested that job satisfaction may mediate the effect of psychological safety on affective commitment. A psychologically safe work atmosphere reduces work-related anxiety and stress, and grants opportunities for skill development and performance improvement,22 which results in higher job satisfaction (path H2a). Such an atmosphere is especially important in medical settings with high requirements for professional knowledge and low fault tolerance rates. For example, research demonstrated that physicians who felt more psychologically safe reported harmonious relationships and effective communication with colleagues.23 Another study found that psychological safety in medical settings encouraged discussion of errors and offering suggestions without fear of negative consequences.24 In addition, previous studies noted that job satisfaction was fundamental to affective commitment both within and beyond medical settings3,25,26 (path H2b). Employees with high job satisfaction are more likely to have positive attitudes and a strong sense of identity and belonging to their organizations than those with low satisfaction.11 A positive and satisfying work experience also implies that employees’ ex-ante job expectations are met or exceeded, and these fulfilled expectations contribute to employees’ commitment.27 Previous studies confirmed that nurses with high job satisfaction reported strong affective commitment to their hospital.28,29 Conversely, employees who were dissatisfied with their jobs were likely to become emotionally disconnected from their organizations.26 Therefore, we hypothesized that job satisfaction would mediate the effect of psychological safety on affective commitment, with increased psychological safety eliciting job satisfaction, which in turn improves affective commitment (H2).

Job Burnout as an Inhibiting Mediator

Job burnout refers to employees’ stress and psychological reactions to work pressure.30 Burnout is commonly defined as a three-component concept including emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and diminished personal accomplishment.31 Severe job burnout is common in healthcare settings as a result of excessive workload, high demand for physicians, risky working environment, and poor doctor-patient relationships.32 Previous research suggested that psychological safety could reduce employee’s job burnout33 (path H3a). A possible reason for this is that psychological conditions may be seen as a reflection of the work environment.34 Employees that perceived low psychological safety were reported to be prone to negative emotions such as burnout.32 Another possible reason is that psychological safety may contribute to coordination and cooperation through tacit teamwork and peer communication,35 which reduces the anxiety and pressure that usually lead to job burnout. Finally, the familiarity brought about by psychological safety may promote a sense of a family-like work environment, improve employees’ social adaptability, and ultimately help employees combat burnout.33 Previous studies also revealed that job burnout could reduce organizational commitment among medical staff36 (path H3b). The conservation of resources (COR) theory has been widely applied in job burnout research, and related to loss of organizational and human resources.37 COR theory proposes that human beings are motivated to protect their existing resources and obtain new resources.38 Therefore, individuals with limited resources tend to save energy, time, and emotion to avoid the loss of these resources.39 Withdrawal as a coping mechanism for job burnout resembles the conservation process of exhausted affective resources.40 Employees may disengage and reduce their affective commitment to their organization to prevent further loss of resources. Alarcon et al’s study also suggested that employees’ commitment deteriorated when job burnout occurred, especially emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, as job burnout and organizational commitment were both affective-oriented constructs.41 Therefore, we hypothesized that job burnout would mediate the effect of psychological safety on affective commitment; that is, increased psychological safety would inhibit job burnout, thereby enhancing affective commitment (H3).

Moderating Role of Perceived Organizational Support

Medical work is characterized by high risk and heavy workloads, which makes external support important for hospital staff when they experience stress. Perceived organizational support (POS) is defined as the extent to which employees believe that their organization values their contributions, cares for their well-being, and accommodates their social and emotional needs.42 The mediating role of burnout may be conditional on POS given that the former reflects typical work-related stress. From the perspective of COR theory, resource gain increases in salience in the context of resource loss.43 Hobfoll suggested that social support can expand one’s resource pool and replace other scarce resources.44 For employees experiencing job burnout, POS can help supplement resources consumed and avoid resource loss, thereby ameliorating the harmful effects of negative emotions45,46 and preserving employees’ connection to their organization. Conversely, employees with low POS are particularly vulnerable to the harmful effects of job burnout, and are more likely to experience decline in their emotional connection with their organization.45 Therefore, we hypothesized that POS may buffer job burnout because of the lack of psychological safety. Consequently, the detrimental effect of job burnout on affective commitment is mitigated. Specifically, our hypothesis was that the effect of job burnout on affective commitment is moderated by perceived organizational support meaning that the effect is weaker with a high level of perceived organizational support (H4).

The Present Study

The purpose of this study was to explore how psychological safety influenced affective commitment through the mediating roles of job satisfaction and job burnout, and clarify the moderating role of perceived organizational support. Our proposed model is summarized in Figure 1.The findings will enrich relevant theory and provide a new perspective for hospital management. A cross-sectional survey was administered to all staff at a local second-grade comprehensive hospital.

|

Figure 1 The hypothesized model. |

Method

Participants and Procedures

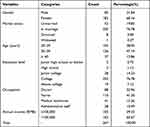

This study was conducted in a second-grade comprehensive hospital in Jiangsu, China. This hospital is representative of typical comprehensive hospitals in China as it includes various clinical, medical technology, and functional departments. Research ethics approval was obtained from Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (SJUPN-202104). Hospital officials were contacted in advance to confirm research approval and coordinate sampling procedures. An anonymous link to an online survey was then distributed to all hospital staff (n = 334) in September 2021. Consent to participate was collected before participants responded to the survey. The survey could be completed within 30 minutes without disruption. In total, 267 valid responses (response rate 79.94%) were received from 85 (31.84%) male and 182 female staff. Of the sample for analysis, 88 (32.96%) were doctors, 110 (41.20%) were nurses, 41 (15.36%) were medical technicians, and 28 (10.49%) were administrative staff. The sample characteristics are presented in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Sample Characteristics (n = 267) |

Measures

The scales selected to measure psychological safety, affective commitment, job burnout, job satisfaction and perceived organizational support in this study were all widely used maturity scales with good reliability and validity and were considered suitable for the participants. The original English language scales were translated into Chinese following the standard translation and back translation procedure. Rewording of items was applied to fit Chinese medical settings as necessary. Content and construct validity tests were performed for all translated scales and some items were deleted for unsatisfactory factor loading (for example, “I do not feel a strong sense of ‘belonging’ to my organization” from the Affective Commitment Scale). For each construct, a composite score was created by averaging all scale items, with higher scores indicating higher levels of that construct.

Psychological Safety

Three items were adapted from Edmondson (1999) to measure psychological safety (for example, “If you make a mistake in your department, it is often held against you”; 1 = very strongly disagree to 7 = very strongly agree).14

Affective Commitment

Three items were adapted from Meyer (1993) to measure affective commitment (for example, “I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this hospital”; 1 = very strongly disagree to 7 = very strongly agree).47

Job Satisfaction

Thirteen items were adapted from the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire to evaluate job satisfaction (for example, “The chance to do something that makes use of my abilities”; 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree).48

Job Burnout

Thirteen items were adapted from the Maslach Burnout Inventory–Human Service Survey to measure job burnout (for example, “I feel depressed at work”; 1 = never to 7 = every day).49,50

Perceived Organizational Support (POS)

Eight items were adopted from Eisenberger’s Perceived Organizational Support Scale to measure perceived organizational support (for example, “My organization really cares about my well-being”; 1 = very strongly disagree to 7 = very strongly agree).42,51

Finally, participants were also asked to report their age, gender, marital status, education level, occupation, and annual income.

Analytical Plan

The psychometric properties of the selected scales were examined before hypothesis testing. Reliability was assessed via internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha values greater than 0.70 considered satisfactory. Validity tests for all translated scales was performed in AMOS version 22.0 against pre-determined acceptable criteria: comparative fit index (CFI) > 0.90, Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) > 0.90,  /df < 3, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.08, and average variance extracted (AVE; which was expected to be larger than the correlation coefficients among the corresponding factors). Mediation and moderated mediation analyses were conducted with the SPSS PROCESS macro52 using 5000 bootstrapping, with age, gender, and annual income included as control variables. All continuous variables were mean-centered in the moderated mediation analysis. The Johnson–Neyman technique was used to identify the statistically significant region for the interaction effect concerning POS.53

/df < 3, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.08, and average variance extracted (AVE; which was expected to be larger than the correlation coefficients among the corresponding factors). Mediation and moderated mediation analyses were conducted with the SPSS PROCESS macro52 using 5000 bootstrapping, with age, gender, and annual income included as control variables. All continuous variables were mean-centered in the moderated mediation analysis. The Johnson–Neyman technique was used to identify the statistically significant region for the interaction effect concerning POS.53

Results

All scales exhibited acceptable reliability (Cronbach’s αs > 0.696). Structural and discriminant validity (Supplementary Figure 1) were also examined. Satisfactory model fit ( (723) = 1.922, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.934; TLI = 0.929; RMSEA = 0.059) supported the conceptual distinctiveness among the five key constructs. Descriptive statistics, Cronbach’s alphas, bivariate correlations, and average variance extracted of the key constructs are presented in Table 2.

(723) = 1.922, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.934; TLI = 0.929; RMSEA = 0.059) supported the conceptual distinctiveness among the five key constructs. Descriptive statistics, Cronbach’s alphas, bivariate correlations, and average variance extracted of the key constructs are presented in Table 2.

|

Table 2 Descriptive Statistics, Correlations, Reliability and Validity Indexes of the Key Constructs |

Mediating Effects of Job Satisfaction and Job Burnout

Results for the mediation analysis are reported in Table 3. Variance inflation factors were below 2.50 for all independent variables and showed no sign of multicollinearity. A full-mediation pattern was observed because the direct effect of psychological safety on affective commitment was statistically significant (BTotal effect = 0.546, standard error [SE] = 0.052, p < 0.001, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.443~0.649), but after accounting for the indirect effects via job satisfaction (BIndirect effect = 0.393, SE = 0.051, 95% CI = 0.295~0.495) and job burnout (BIndirect effect = 0.069, SE = 0.060, 95% CI = 0.207~0.446), the direct effect was no longer significant (BDirect effect = 0.084, SE = 0.048, p = 0.082, 95% CI = −0.011~0.179). This implied that for every 1-unit increase in psychological safety, affective commitment was expected to increase by 0.393 units via (increased) job satisfaction and by 0.069 units via (decreased) job burnout. Therefore, hypotheses 1, 2, and 3 were supported. Figure 2 shows a summary of the regression results.

|

Table 3 The Mediating Effects of Job Satisfaction and Job Burnout Between Psychological Safety and Affective Commitment |

Moderation Effect of POS

We further analyzed the moderation effect of POS. The results (Table 4 and Figure 3) suggested that POS only significantly moderated the indirect effect from psychological safety to affective commitment via job burnout (index of moderated mediation = −0.047, SE = 0.022, 95% CI = −0.086~−0.001). Although POS moderated the effect of job satisfaction on affective commitment (namely, path H2b; B = 0.165, SE = 0.073, p = 0.025, 95% CI = 0.021~0.308), it did not moderate the corresponding indirect effect (index of moderated mediation = 0.061, SE = 0.029, 95% CI = −0.004~0.110).

|

Table 4 The Moderated Mediation Analysis |

The Johnson–Neyman technique showed the threshold of the moderation effect of the POS score was 0.250 (Figure 4), below which the effect of job burnout on affective commitment was significant. Within this POS score range (−4.376~0.250), the conditional effect of job burnout on affective commitment decreased as POS increased (from −0.776 to −0.132), as did the corresponding indirect effect (from 0.044 to 0.026). We further decomposed this moderated mediation through simple slope analysis. For hospital staff that reported lower POS (namely, M −1 standard deviation [SD]), lack of psychological safety contributed to higher job burnout, and consequently less affective commitment (BIndirect effect = 0.108, SE = 0.042, 95% CI = 0.029~0.194). However, this deleterious mediation effect was not observed for those who reported high POS (namely, M +1 SD; BIndirect effect = 0.004, SE = 0.032, 95% CI = −0.053~0.073).

Discussion

This study found that job satisfaction and job burnout fully mediated the relationship between psychological safety and affective commitment; that is, psychological safety enhanced affective commitment through improving job satisfaction and reducing job burnout. This study also found that perceived organizational support moderated the mediating effect of job burnout between psychological safety and affective commitment, whereby high POS counteracted the deleterious effect of job burnout on affective commitment. However, POS did not moderate the path via job satisfaction.

Theoretical Implications

The present investigation contributed to healthcare management research in several ways. First, previous studies confirmed the positive correlation between psychological safety and affective commitment, but most empirical findings came from nursing staff.16 Our study investigated doctors, nurses, medical technicians, and administrative staff, and provided a comprehensive picture of human resources in medical settings (see Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 for multiple-group mediation analyses). Therefore, our study broadens the application of the effect of psychological safety on affective commitment and enriches the literature by providing a new perspective for hospitals to retain talent.

Second, although a positive correlation between psychological safety and affective commitment has been reported among employees in other industries,16,18,54 the underlying mechanism remains unclear. The medical industry is essentially a service industry characterized by serious concerns about job satisfaction and job burnout. This study explored the mechanisms influencing the relationship between psychological safety and affective commitment from both the positive (namely, improving job satisfaction) and negative (namely, reducing job satisfaction) perspectives. The results revealed that job satisfaction and job burnout played separate and distinct mediating roles. Therefore, in addition to exploring promoting or inhibiting pathways in relevant topics, further studies should consider possible modes of both directions. Dawon Baik et al’s research focused on nurses also supported our results and suggested a supportive team atmosphere, such as sufficient psychological safety, could mitigate workplace frustration and make employees more satisfied with their jobs and more likely to stay in their jobs.19 Our findings also echo Hoff et al’s observation11 that workplaces in which physicians felt in control of their jobs without undue stress and were satisfied with their jobs were likely to gain enhanced commitment. As negative psychological processes often have stronger effects than positive ones,55(reducing) job burnout offers a substantial way to counteract commitment issues induced by the lack of psychological safety.

Finally, this study found an important boundary condition in the impact of psychological safety on affective commitment. Our results suggested that external organizational support can mitigate the negative effect of job burnout on affective commitment, which empirically extends the COR theory such that the access to additional resources can make up for the loss of resources.46 Employees from collectivistic cultures such as China are more likely to take advantage of POS to buffer job-relevant stress56 through capitalizing on a series of positive emotional perceptions and experiences in the workplace to supplement depleted emotional resources and maintain affective commitment.57 Chinese hospitals have been experiencing low doctor-patient ratios, poor doctor-patient relationships, and excessive work hours for many years. POS plays an important role in alleviating the negative impact of job burnout caused by low psychological safety for hospital employees and helping them develop a sense of belonging and increased affective commitment by satisfying their social emotional needs.58

Practical Implications

Previous studies concluded that high levels of organizational commitment among physicians, especially affective commitment, were associated with favorable outcomes such as improved care quality and productive work behaviors.4,7 A general perception, at least in China, is that medical staff are relatively more committed to their institutions and less frequently switch institutions, compared to other service industries. However, our results suggested that staff turnover could be high if medical staff’s affective commitment was at risk due to (low) job satisfaction or (high) job burnout. Special attentions should be warranted to cases where healthcare workload increases in various emergencies, such as the current pandemic situation to avoid talent drain.59,60 Our results provided insights for improving the affective commitment among hospital employees.

First, this study demonstrated psychological safety had a positive effect on affective commitment. In particular, when employees have low POS, enhancing psychological safety is important to increase affective commitment by reducing job burnout. Hospitals can implement measures such as applying people-oriented management, creating a collaborative work atmosphere, and establishing verbal encouragement mechanisms54 to improve employees’ psychological safety and ultimately improve employees’ affective commitment.

However, psychological safety is not always granted in hospitals given the fixed professional hierarchy and low fault tolerance. As our results suggested, alternatively, hospitals can consider increasing job satisfaction and/or decreasing job burnout. On one hand, hospitals could attach more importance to the welfare of hospital staff and implement reasonable merit-based incentive systems.61 Meanwhile, employee’s professional development opportunities could be provided to help junior employees’ career development62 so they can realize their personal values and achievements and boost their job satisfaction.On the other hand, most job burnout interventions for healthcare teams aimed at individual-level factors (such as adjustment of work hours) and the application of new equipment and technologies. However, contagious negative affective states were somewhat neglected,39 and our results shed light on the particular role of organizational support in terms of limiting such harmful effect from job burnout. Hospitals may invest in emotional support, such as strengthening communication between employees and supervisors, to establish relationships with trust and support,61 and instrumental support, such as setting up family-friendly policies to help employees balance work-family conflicts.63

Limitations

Our study was somewhat limited by its cross-sectional design. Such design precluded us from probing the causal relationship between job satisfaction, job burnout (namely, the mediators), and affective commitment (namely, the dependent variable). However, as the causal relationship could be reversed64 or reciprocal65 in realistic settings, our investigation emphasized the motivational essence of affective commitment and provided unique insights as to how modern hospitals could enhance affective commitment via the identified mechanisms to boost their employee’s positive attitude, and consequently, their dedication towards the organization.

Conclusion

To keep hospital employees emotionally attached and dedicated to the organization, this study revealed that psychological safety can boost affective commitment via (increasing) job satisfaction and (decreasing) job burnout. Furthermore, perceived organizational support could counteract the deleterious effect of job burnout on affective commitment. Our findings make significant contributions to healthcare management research and practice.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets used or analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

Research ethics approval was obtained from Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (SJUPN-202104). The procedures used in this study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants gave electronic informed consent before participating in the online questionnaire.

Consent for Publication

All authors agreed with the publication of this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Audrey Holmes for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Jiahui Li and Sisi Li are Co-first authors.

Funding

No sources of funding were received to conduct this study or to prepare this manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Meyer JP, Allen NJ. A three complement conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum Resour Manag Rev. 1991;1(1):64–89. doi:10.1016/1053-4822(91)90011-Z

2. Meyer JP, Stanley DJ, Herscovitch L, Topolnytsky L. Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: a meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. J Vocat Behav. 2002;61(1):20–52. doi:10.1006/jvbe.2001.1842

3. Koo B, Yu J, Chua B-L, Lee S, Han H. Relationships among emotional and material rewards, job satisfaction, burnout, affective commitment, job performance, and turnover intention in the hotel industry. J Qual Assur Hosp Tour. 2020;21(4):371–401. doi:10.1080/1528008X.2019.1663572

4. Horwitz SK, Horwitz IB. The effects of organizational commitment and structural empowerment on patient safety culture. J Health Organ Manag. 2017;31(1):10–27. doi:10.1108/JHOM-07-2016-0150

5. Akar H. The relationships between quality of work life school alienation burnout affective commitment and organizational citizenship. A study on teachers. Eur J Educ Res. 2018;7(2):169–180. doi:10.12973/eu-jer.7.2.169

6. Meyer JP, Maltin ER. Employee commitment and well-being: a critical review, theoretical framework and research agenda. J Vocat Behav. 2010;77(2):323–337. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2010.04.007

7. Liu C, Bartram T, Casimir G, Leggat SG. The link between participation in management decision-making and quality of patient care as perceived by Chinese doctors. Public Manag Rev. 2015;17(10):1425–1443. doi:10.1080/14719037.2014.930507

8. Fleig-Palmer MM, Rathert C. Interpersonal mentoring and its influence on retention of valued health care workers: the moderating role of affective commitment. Health Care Manage Rev. 2015;40(1):56–64. doi:10.1097/HMR.0000000000000011

9. Leong L, Huang SY, Hsu J. An empirical study on professional commitment, organizational commitment and job involvement in Canadian accounting firms; 2003;2.

10. Wallace. Professional and organizational commitment: compatible or incompatible? Acad Press. 1993;42(3):333–349.

11. Hoff T, Lee DR, Prout K. Organizational commitment among physicians: a systematic literature review. Health Serv Manag Res. 2021;34(2):99–112. doi:10.1177/0951484820952307

12. Lyman B, Gunn MM, Mendon CR. New graduate registered nurses’ experiences with psychological safety. J Nurs Manag. 2020;28(4):831–839. doi:10.1111/jonm.13006

13. Takase M, Yamashita N, Oba K. Nurses’ leaving intentions: antecedents and mediating factors. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(3):295–306. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04554.x

14. Edmondson A. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm Sci Q. 1999;44(2):350–383. doi:10.2307/2666999

15. Clercq DD, Rius IB. Organizational commitment in Mexican small and medium‐sized firms: the role of work status, organizational climate, and entrepreneurial orientation. J Small Bus Manag. 2007;45(4):467–490. doi:10.1111/j.1540-627X.2007.00223.x

16. Rathert C, Ishqaidef G, May DR. Improving work environments in health care: test of a theoretical framework. Health Care Manage Rev. 2009;34(4):334–343. doi:10.1097/HMR.0b013e3181abce2b

17. Basit AA. Trust in supervisor and job engagement: mediating effects of psychological safety and felt obligation. J Psychol. 2017;151(8):701–721. doi:10.1080/00223980.2017.1372350

18. Kirk-Brown A, Dijk PV. An examination of the role of psychological safety in the relationship between job resources, affective commitment and turnover intentions of Australian employees with chronic illness. Int J Hum Res Manag. 2016;27(14):1626–1641. doi:10.1080/09585192.2015.1053964

19. Baik D, Zierler B. Clinical nurses’ experiences and perceptions after the implementation of an interprofessional team intervention: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28(3–4):430–443. doi:10.1111/jocn.14605

20. Merandi J, Liao N, Lewe D, et al. Deployment of a second victim peer support program: a replication study. Pediatr Qual Saf. 2017;2(4):e031. doi:10.1097/pq9.0000000000000031

21. Nielsen MB, Mearns K, Matthiesen SB, Eid J. Using the job demands-resources model to investigate risk perception, safety climate and job satisfaction in safety critical organizations. Scand J Psychol. 2011;52(5):465–475. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9450.2011.00885.x

22. Kim M-J, Kim B-J. Analysis of the importance of job insecurity, psychological safety and job satisfaction in the CSR-performance link. Sustainability. 2020;12(9):3514. doi:10.3390/su12093514

23. Yanchus NJ, Derickson R, Moore SC, Bologna D, Osatuke K. Communication and psychological safety in veterans health administration work environments. J Health Organ Manag. 2014;28(6):754–776. doi:10.1108/JHOM-12-2012-0241

24. Stühlinger M, Schmutz JB, Grote G. I Hear You, but Do I Understand? The relationship of a shared professional language with quality of care and job satisfaction. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1310. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01310

25. Benevene P, Dal Corso L, De Carlo A, Falco A, Carluccio F, Vecina ML. Ethical leadership as antecedent of job satisfaction, affective organizational commitment and intention to stay among volunteers of non-profit organizations. Front Psychol. 2018;9:2069. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02069

26. Ampofo ET. Mediation effects of job satisfaction and work engagement on the relationship between organisational embeddedness and affective commitment among frontline employees of star–rated hotels in Accra. J Hosp Tourism Manag. 2020;44:253–262. doi:10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.06.002

27. Tannenbaum SI, Mathieu JE, Salas E, Cannon-Bowers JA.Meeting trainees’ expectations: the influence of training fulfillment on the development of commitment, self-efficacy, and motivation. J Appl Psychol. 1991;76(6):759–769. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.76.6.759

28. Chang CS, Chang HH. Effects of internal marketing on nurse job satisfaction and organizational commitment: example of medical centers in Southern Taiwan. J Nurs Res. 2007;15(4):265–274. doi:10.1097/01.JNR.0000387623.02931.a3

29. Ho WH, Chang CS, Shih YL, Liang RD. Effects of job rotation and role stress among nurses on job satisfaction and organizational commitment. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9(1):8. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-9-8

30. Cordes CL, Dougherty TWA. Review and an integration of research on job burnout. Acad Manag Rev. 1993;18(4):621–656. doi:10.2307/258593

31. Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Occup Behav. 1981;2(2):99–113. doi:10.1002/job.4030020205

32. Aronsson G, Theorell T, Grape T, et al. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):264. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4153-7

33. Swendiman RA, Edmondson AC, Mahmoud NN. Burnout in surgery viewed through the lens of psychological safety. Ann Surg. 2019;269(2):234–235. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003019

34. Kahn WA. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad Manag J. 1990;33(4):692–724.

35. Ortega A, Sánchez-Manzanares M, Gil F, Rico R. Team learning and effectiveness in virtual project teams: the role of beliefs about interpersonal context. Span J Psychol. 2010;13(1):267–276. doi:10.1017/S113874160000384X

36. Spence Laschinger HK, Leiter M, Day A, Gilin D. Workplace empowerment, incivility, and burnout: impact on staff nurse recruitment and retention outcomes. J Nurs Manag. 2009;17(3):302–311. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2009.00999.x

37. Obrenovic B, Jianguo D, Khudaykulov A, Khan MAS. Work-family conflict impact on psychological safety and psychological well-being: a job performance model. Front Psychol. 2020;11:475. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00475

38. Halbesleben JR, Neveu JP, Paustian-Underdahl SC, Westman M. Getting to the “COR”: understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. J Manage. 2014;40(5):1334–1364. doi:10.1177/0149206314527130

39. Liu C, Cao J, Zhang P. Investigating the relationship between work-to-family conflict, job burnout, job outcomes, and affective commitment in the construction industry. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(16):5995. doi:10.3390/ijerph17165995

40. Tabor W, Madison K, Marler LE, Kellermanns FW. The effects of spiritual leadership in family firms: a conservation of resources perspective. J Bus Ethics. 2020;163:729–743.

41. Alarcon GM. A meta-analysis of burnout with job demands, resources, and attitudes. J Vocat Behav. 2011;79(2):549–562.

42. Eisenberger R, Huntington R, Hutchison S, Sowa D. Perceived organizational support. J Appl Psychol. 1986;71(3):500–507. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.500

43. Hobfoll SE, Halbesleben J, Neveu JP, Westman M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: the reality of resources and their consequences. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2018;5(1):103–128. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640

44. Hobfoll SE. The Ecology of Stress. New York: Hemisphere; 1988.

45. Alcover CM, Chambel MJ, Fernández JJ, Rodríguez F. Perceived organizational support-burnout-satisfaction relationship in workers with disabilities: the moderation of family support. Scand J Psychol. 2018;59(4):451–461. doi:10.1111/sjop.12448

46. Zeng X, Zhang X, Chen M, Liu J, Wu C. The influence of perceived organizational support on police job burnout: a moderated mediation model. Front Psychol. 2020;11:948. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00948

47. Meyer JP, Allen NJ, Smith CA. Commitment to organizations and occupations: extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. J Appl Psychol. 1993;78(4):538–551. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.78.4.538

48. Weiss D, Dawis R, England G. Manual for the Minnesota satisfaction question; 1967:Vol XXII.

49. Jackson SE Maslach burnout inventory-human service survey (MBI-HSS). 1996.

50. Chaoping L, Kan S, Zhengxue L, Li L, Yue Y. An investigation on job burnout of doctor and nurse. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2003;03:170–172.

51. Eisenberger R, Cummings J, Armeli S, Lynch P. Perceived organizational support, discretionary treatment, and job satisfaction. J Appl Psychol. 1997;82(5):812–820. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.82.5.812

52. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: The Guilford Press; 2013.

53. Miller JW, Stromeyer WR, Schwieterman MA. Extensions of the Johnson-Neyman technique to linear models with curvilinear effects: derivations and analytical tools. Multivariate Behav Res. 2013;48(2):267–300. doi:10.1080/00273171.2013.763567

54. Liu X, Yang S, Yao Z. Silent counterattack: the impact of workplace bullying on employee silence. Front Psychol. 2020;11:572236. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.572236

55. Baumeister RF, Bratslavsky E, Finkenauer C, Vohs KD. Bad is stronger than good. Rev Gen Psychol. 2001;5(4):323–370. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.5.4.323

56. Hur WM, Han SJ, Yoo JJ, Moon TW. The moderating role of perceived organizational support on the relationship between emotional labor and job-related outcomes. Manag Decis. 2015;53(3):605–624. doi:10.1108/MD-07-2013-0379

57. Riggle RJ, Edmondson DR, Hansen JD. A meta-analysis of the relationship between perceived organizational support and job outcomes: 20 years of research. J Bus Res. 2008;62(10):1027–1030. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.05.003

58. Abou Hashish EA. Relationship between ethical work climate and nurses’ perception of organizational support, commitment, job satisfaction and turnover intent. Nurs Ethics. 2017;24(2):151–166. doi:10.1177/0969733015594667

59. Al-Mansour K. Stress and turnover intention among healthcare workers in Saudi Arabia during the time of COVID-19: can social support play a role? PLoS One. 2021;16(10):e0258101. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0258101

60. Falatah R. The impact of the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic on nurses’ turnover intention: an integrative review. Nurs Rep. 2021;11(4):787–810. doi:10.3390/nursrep11040075

61. Liu W, Zhao S, Shi L, et al. Workplace violence, job satisfaction, burnout, perceived organisational support and their effects on turnover intention among Chinese nurses in tertiary hospitals: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(6):e019525. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019525

62. Guo H, Guo H, Yang Y, Sun B. Internal and external factors related to burnout among iron and steel workers: a cross-sectional study in Anshan, China. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0143159. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0143159

63. Li X, Zhang Y, Yan D, Wen F, Zhang Y. Nurses’ intention to stay: the impact of perceived organizational support, job control and job satisfaction. J Adv Nurs. 2020;76(5):1141–1150. doi:10.1111/jan.14305

64. Wayoi DS, Margana M, Prasojo LD, Habibi A. Dataset on Islamic school teachers’ organizational commitment as factors affecting job satisfaction and job performance. Data Brief. 2021;37:107181. doi:10.1016/j.dib.2021.107181

65. Markovits Y, Davis AJ, Fay D, Dick R. The link between job satisfaction and organizational commitment: differences between public and private sector employees. Int Public Manag J. 2010;13(2):177–196. doi:10.1080/10967491003756682

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.