Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 8

Professionalism among paramedic students: achieving the measure or missing the mark?

Authors Bowen LM , Williams B , Stanke L

Received 19 March 2017

Accepted for publication 5 July 2017

Published 20 October 2017 Volume 2017:8 Pages 711—719

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S137455

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Md Anwarul Azim Majumder

L Michael Bowen, Brett Williams, Luke Stanke

Department of Community Emergency Health and Paramedic Practice, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, Clayton, VIC, Australia

Background: Professionalism is a pillar of paramedicine. Internationally paramedic curricula emphasize valid assessment of three domains: cognitive, psychomotor, and affective domains (professionalism). Little is reported on competency measures for professionalism specific to paramedicine. Literature suggests that paramedic students, paramedic practitioners, medical directors, and patients believe that professional attributes should have an increased focus.

Objective: The objective of this scoping review is to outline valid and reliable assessments that evaluate professional behaviors.

Method: This review used Arksey and O’Malley’s six-stage scoping methodology. In September 2016, five databases were searched for articles of relevance; these were MEDLINE, Scopus, Google Scholar, PsycINFO/APA, and EMBASE.

Results: A total of 1587 articles were identified after removal of 468 duplicates. Five articles met the inclusion criteria, two of the articles were from the US and three from UK. The studies range from 2004 to 2014. Three different scales were identified but only two were recommended for use. A US-based scale is composed of 11 items and one generic form of professionalism. The UK scale has 77 items and identified 11 factors within 68 items.

Conclusions: This scoping review serves to describe valid and reliable measures for professionalism among paramedicine by outlining the quantity of instruments evident in the literature. The scoping review aimed to report the scales supporting evidence of validity and reliability. Three scales were identified in a total of five different studies that specifically measured professional attributes in paramedicine. Currently, two scales are available: an evaluation with 11 items and a self-reported questionnaire with 77 items.

Keywords: paramedicine, EMS, measurement, professional behavior, affective domain, emergency medical technician, ambulance

Introduction

Professionalism and professional behaviors are an intrinsic aspect of paramedicine. Thus, these core competencies must be assessed with a valid and reliable evaluation. Paramedic curricula emphasize assessment of cognitive, psychomotor, and affective domains with valid tools. A disparity exists between curricula, paramedic students’ beliefs,1 and agencies that employ paramedic practitioners,2 but reflects the most frequent complaint against paramedics.3 Professional behavior evaluations should be precise or the efforts of paramedic educators are diluted by a fundamental flaw of inaccurate measurements.4

The transition of an occupation being recognized is professionalization5 and these changes are initiated in the academic setting.1 As paramedic education transitions into higher education settings the landscape is primed for an overhaul.6 A professional status is earned;7 it is the responsibility of the occupation to act professionally. A professional status is earned, it is the responsibility of the occupation to act professional. The transition process was summarized by Williams et al and identify a publicly recognized certification agency at the next required step in professionalization.8 Achieving a professional status is arguably the most pressing issue in paramedicine.9

Historically literature does not have a universal definition of professionalism. In 1915, Abraham Flexner theorized six generic traits of an occupation to be seen as a profession: involve essentially intellectual operations with large individual responsibility; derive their raw material from science and learning; they work up on this material to a practical and definite end; they possess an educationally communicable technique; they tend to self-organize; they are becoming increasingly altruistic in motivation.10 In 1957, Greenwood theorized a generic list of five attributes that accounted for overlaps in occupations.5

In 1945, nursing identified six aspects of nursing professionalism. The body of knowledge must be taught in a higher education setting, must have practical knowledge transfer, and must constantly expand. Additionally, it should emphasize an altruistic approach to patient care while functioning autonomously.11 In recent years professional behaviors for physicians have been described by Cruess and Cruess12 Swick,13 Steinert et al.14 Table 1 describes professional characteristics dating back over 100 years. It is worth noting how certain traits such as altruism, autonomy, body of knowledge, scientific approaches, and code of ethics transcend time and occupations.

| Table 1 Professional characteristics over 100 years Note: *Generic occupational trait. |

Paramedic programs are increasingly encouraged to standardize summative assessments that take a holistic approach to patient encounters, and these competencies are not limited to technical skills.16 This standardized competency approach “delineates key technical, cognitive, and emotional aspects of practice, including those that may not be measurable”17 albeit physically measurable is more accurate. Quantifying professionalism and the trajectory of learning a competency require a different approach that is a series of objective observations at individual, interpersonal, and societal/institutional levels.18 A single assessment in an isolated setting does not accurately reflect abilities and more observations result in a more precise assessment.19

Nurses and physicians have used students to validate professional behavior scales. Physicians identified professionalism as a core clinical requirement, and in 1998 the Physicianship Evaluation Form was validated20 and in 2005 the Amsterdam Attitude and Communication Scale was validated.21 Nurses also view professionalism as an essential part of patient care, and in 2000 the Nursing Professional Values Scale22 was developed, then in 2003 the Professionalism Inventory Scale.23 Pharmacy validated the Professional Assessment Tool in 2011 with seven institutions participating in the study.24

Professionalism is a requirement across numerous international paramedic curricula.25–29 In the US professional behaviors were originally included in the 1998 emergency medical technician (EMT)-Paramedic National Standard Curriculum30 and repeated in the 2002 EMT-Paramedic National Standard Curriculum.26 To ensure that these competencies are met, the Committee on Accreditation of Educational Programs for the Emergency Medical Services Professions requires documentation of a summative affective evaluation for each graduating student.31,32 Acting unprofessionally has significant consequence and may lead to dismissal.33 Internationally paramedicine moves toward being viewed as a profession but each country has a unique set of challenges ahead.

The Canadian paramedic curriculum requires paramedic students to display 10 professional behaviors throughout practice.27 In the UK, the College of Paramedics Curriculum Guidance is used in educating paramedics and identifies three domains of learning; cognitive, psychomotor, and affective. It specifically identifies while on clinical placement student paramedics are expected to: “Constantly demonstrate a high level or professionalism.”34 As a paramedic practitioner, professional conduct requirements are required for certain certifications.28

In Australia paramedics have made significant progress to become a well-respected profession. The public views paramedicine as a trustworthy profession35 and the government is poised to recognize it as a profession.36

How are key terminology defined?

It is important to calibrate nomenclature when referencing international topics. The affective domain attributes are feelings, appearance, emotional response, attitudes, and behaviors.25,27,31,32,37,38 The affective domain, professionalism traits/behaviors, and professionalism are used interchangeably in this paper depending on the context. Validity is how well evidence and theory support test scores. Common expectations require test developers to display the values of the measure for content validity.19,39 Reliability is the consistency of score across replications of the test.40 Questions are items and refer to how a scale is composed.

Methods

The methodology of a scoping review was considered appropriate for this study to examine the depth, breadth, and research activity. This study utilized a scoping review method to investigate if paramedics or paramedic students are evaluated with valid and reliable evaluations. This scoping review was guided by Arksey and O’Malley’s41 six-stage methodology for scoping reviews. These stages included:

- Identifying the research question

- Identifying the relevant studies

- Selecting the study

- Charting the data

- Collating, summarizing, and reporting results

- Consulting an expert (optional and included).

The methodology identifies five mandatory stages with an optional sixth stage of consultation. The authors selected to include the additional step to help validate results.

Identify the research question

Given the significance of professional behaviors and the scant amount of literature available on whether a professionalism scale is psychometrically appropriate for emergency medical services, the following research question was developed to inform the scoping review: “Are paramedic students evaluated with a valid and reliable measurement tool for professionalism?”

Identify relevant studies

Five databases were searched for articles of relevance; these were MEDLINE, Scopus, Google Scholar, PsycINFO/APA, and EMBASE. The grey literature sites http://www.greylit.org/ and http://www.tripdatabase.com/ were also searched for non-peer-reviewed literature, which yielded no additional results. Along with this dissertation, forward and backward reference searching and hand searching were also conducted. Publications were not limited to a date range because of the previous knowledge of the Brown et al article,43 and no relevant studies were identified before this year. The search terms used in the strategy included “paramedic,” “paramedic student,” “professionalism,” “affective domain,” “professional role,” “measurement,” “reproducibility of results,” “questionnaire,” and “soft skill.” The search was executed by one author (LMB) and refined by LS and BW. An expert librarian validated the search strategy. The inclusion and exclusion of articles was decided upon between LMB and BW. The Supplementary material outlines the complete list of keywords.

Study selection

The search of the five databases returned a total of 2055 articles and 468 duplicates. The 1587 articles remaining were screened by title and abstract. A total of seven articles met the inclusion criteria. After a full paper screening, five articles fulfilled the inclusion criteria:

- Articles focused on paramedicine OR paramedics OR paramedic students

- Measure professionalism OR professional behaviors OR affective domain

- Articles that reported more than descriptive statistics (reliability, internal consistency, p values, and so on)

- Self-reported or evaluated professional behaviors.

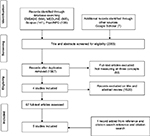

Articles not in English or with subjective measured results were excluded from the study. This screening process captured four articles included in the review. Figure 1 displays search results and process of study selection.

| Figure 1 Search results and study selection. |

Arksey and O’Malley41 describe the charting of the data stage as a narrative and analytical approach to identifying data from articles that meet the research aim. Articles were grouped by publication year, author, study location, study type, cohort size, and main finding. Table 1 outlines the five articles selected for this scoping review.

Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

The five articles included for this review had three unique questionnaires with ordinal scales. Two studies originated from the US; these data were collected on working paramedics by peer reviews. The other three studies originated from the UK. Phase I investigated and developed the questionnaire and Phase II was data collection of self-reported responses from paramedics and paramedic students.

Consultation

In an effort to help authenticate that these four articles were a comprehensive list, seven subject matter experts (SMEs) were contacted independently to help identify additional peer-reviewed articles, essays, or grey literature. At this point, only four articles were known, and the fifth was identified later in the process while finding citations. Six of the seven SMEs responded to the expert consultation. The SMEs were provided the list of four articles and asked if the list was comprehensive for valid and reliable measures to evaluate professionalism within paramedicine. Each SME reviewed the list and provided no additional articles.

Discussion

Of the five articles that met the inclusion criteria, two of the articles were from the US and three from UK. Four of the studies were cross-sectional and examined paramedics and paramedic students. One study was a qualitative workgroup for scale development. The studies range from 2004 to 2014. The results are displayed in Table 2. The aim of this scoping literature review was to map available scales that measure professional behaviors among paramedics or paramedic students. These articles will be discussed now.

| Table 2 Overview of included articles |

Evaluation with a five-point scale

The James and Lindstrom42 study involved five paramedic educators and assessed 222 fire department-based paramedics with the Professional Behavior Evaluation (PBE), an instrument published in the 1998 EMT-Paramedic National Standard Curriculum.30 The educators followed paramedics on 8-hour shifts and rated professionalism with a 1–5-point rubric. The PBE has 11 items: integrity, empathy, self-motivation, appearance, self-confidence, communications, time management, teamwork diplomacy, respect, patient advocacy, and careful delivery of service. After principal component analysis, only one generic type of professionalism was identified. The Cronbach alpha coefficient values ranged from 0.46 to 0.79 suggesting that the variance within total score results by each educator was unreliable for recommended use. Researchers suggested that additional studies should focus on assessing additional behaviors.

Evaluation with a binary scale

Brown et al’s study utilized a modified PBE scale from James and Lindstrom with binary responses.43 An 11-item questionnaire was disseminated by randomly selecting nationally registered paramedics in the US and asked participants to evaluate the partner whom they worked most closely with in the past year. The questionnaire response rate was 62% (n=2443) with an overall mean score of 0.68. Integrity had the highest score (0.77) and self-motivation (0.61) the lowest. Integrity falls under code of ethics,33 which is a trait included in professionalism since 1957. The PBE has generic professionalism traits identified by Flexner10 and Greenwood5 such as altruism and patient advocacy. It is worth noting that the PBE has items not identified elsewhere in literature as a professional trait like “appearance and personal hygiene.” These behaviors could be unique societal expectations specific to US paramedicine.13,44 This evaluation has practical implications with collecting objective assessments in a variety of unique settings where peers, preceptors, and educators are evaluators.18,45

Qualitative scale development

The study by Burford et al was a qualitative one with two phases to assess professional behaviors and conscientiousness index.46 The aim of this study identified SMEs from an ambulance agency and a university. Paramedic educators communicating with an ambulance agency is a key calibration to develop fair, achievable expectations.47,48 The think tank group identified objective behaviors that reflected heightened levels of conscientiousness by collecting routine data about attendance and adherence to deadlines. The SMEs also created a framework for desirable professional behaviors. High instances of conscientiousness are evident with goal-oriented behaviors and attention to detail49 and correlate with agreeableness, a fundamental skill for patient assessment.50 Conscientiousness also correlates with empathy,51 and empathetic behaviors lead to decreased hospital stays and increased patient satisfaction ratings.52–54

Self-reports of professionalism

Burford et al’s was the second report of the 5-year study.44 The questionnaire consisted of 79 items. Seventy-seven items used a ranked 1–5 response: professional identity; professional status; adherence to ethical practice principles; interactions with patients; interactions with staff; reliability; competency, knowledge, and improvement; pride in the profession; appearance; flexibility; behavior outside work; and organizational context. The remaining two items were global measures utilized for anchoring purposes and acquired from the American Board of Internal Medicine’s Project Professionalism.55,56

A total of 323 responses were captured from either paramedic or paramedic students. A total of three locations were sampled, two were ambulance agencies and one a university. A total of 113 qualified paramedics responded to the questionnaire, the average years worked as a qualified paramedic was 11 and ranged from 2–37 years.

Exploratory factory analysis identified 11 factors within 68 items and a fit 0.85 (p<0.001). The reliability of 10 of the 11 factors meets or exceeds reliability threshold of ≥0.70 with value ranges from 0.68 to 0.81. Organizational support had the highest threshold (0.81) and adherence to rules had the lowest (0.68). This scale identifies a transparent approach to measuring self-reported professional behaviors, and psychometric findings suggest that the scale is valid and reliable. It is worth stating the overlapping attributes with Brown et al but required >60% more items. The researchers acknowledged the relatively high number of items but this scale fits their aim.

Qualitative views of cross-discipline professional traits

Burford et al’s was a qualitative study to investigate the attributes of professionalism across three disciplines: paramedicine, occupational therapy, and podiatry.44 A series of 20 focus groups consisted of 112 participants from an ambulance agency, two universities, and one college. Exact definitions of professionalism vary but most attributes stem from three categories. This paper was discovered during the reference and citation search. It was then added to results after author consultation.

The design and development of performance assessments such as professional behaviors should reflect the fidelity of paramedic practice and elicit identical responses. Clear expectations for performance assessments and providing care to patients must be a transparent and a predetermined standard, which bolsters validity and reliability.57

Limitations

Scoping literature review is a relatively new process in health care. While systematic reviews address specific questions, a scoping review flourishes when it seeks to identify a broad question. The focus was on identifying what instruments are available and report their values. The lack of medical subject heading terms designated for paramedics introduces unnecessary error into concept searches. Time constraints and resources may have affected the amount of data and literature found for this review. To the authors’ knowledge, no other scoping reviews are available to compare results.

Future research

This scoping review provided an initial description of articles that aim to measure professional behaviors in paramedicine. In doing so, a mismatch of requirements in paramedic curricula versus ability to evaluate professional behaviors with valid and reliable methods has been established. The number of guidelines, standards, and curricula that require measurement of professional competencies far exceeds the feasibility to measure those.

Questionnaires are useful to understand a baseline measurement of self-reported levels but more research is needed to provide an assessment designed for peer evaluators with different approaches to objective observations of individual, interpersonal, and institutional levels. Future studies should utilize qualitative approach for establishing guidelines and standard setting while quantitative for data collection of scales.

Future data analyses of polytomous items scales should focus on item response theory (IRT). Analyses with IRT are sample-independent estimates of ability that achieve stronger statistical profiles.40,58 A drawback of IRT is that it requires large sample sizes but this requirement can be met with collaboration between educational institutes. Additionally, item fairness should be analyzed with differential item function (DIF).40 A DIF test compares discrepancies between two groups such as males, females, or different ethnic groups with similar overall scores.59 It would be unfair for a group with the same ability to pass or even fail an evaluation for no other reason that being who they are. DIF analysis evaluates for fairness at the item level.

Conclusions

This scoping review serves to outline scales for measuring professional behavior among paramedics by describing what is available in literature. The scoping review aimed to report the scales supporting evidence of validity and reliability. Three scales were identified in a total of five different studies that specifically measured professional attributes in paramedicine. Currently two scales are available, an 11-item rubric and a self-reported questionnaire with 77 items.

This scoping review provides guidance with future research of measuring professional attributes in paramedicine by highlighting the suggested scales that should be used to identify strengths or weaknesses. Professionalism has significant connections between paramedics working collaboratively in a large health care system to meet individual, peer, and societal expectations while adhering to standards of excellence.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflict of interest in this work.

References

Williams B, Fielder C, Strong G, Acker J, Thompson S. Are paramedic students ready to be professional? An international comparison study. Int Emerg Nurs. 2015;23(2):120–126. | ||

Kilner T. Desirable attributes of the ambulance technician, paramedic, and clinical supervisor: findings from a Delphi study. J Emerg Med. 2004;21(3):374–378. | ||

Colwell C, Pons P, Pi R. Complaints against an EMS system. J Emerg Med. 2003;25(4):403–408. | ||

Arnold L. Assessing professional behavior: yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Acad Med. 2002;77(6):502–515. | ||

Greenwood E. Attributes of a Profession. Social Work. 1957;2(3):45–55. | ||

O’Brien K, Moore A, Dawson D, Hartley P. An Australian story: paramedic education and practice in transition. AJP. 2014;11(3). | ||

Reynolds L. Is prehospital care really a profession? Australasian Journal of Paramedicine. 2004;2(1–2):1–6. | ||

Your Transition Plan: From EMT Paramedic to Paramedic [press release]. nremt.org: The National Registry of Emergency Medical Technicians, Fall 2011. | ||

Williams B, Onsman A, Brown T. From stretcher-bearer to paramedic the Australian paramedics’ move towards professionalisation. Australasian Journal of Paramedicine. 2009;7(4):1–12. | ||

Flexner A. Is Social Work a Profession? Proceedings of the National Conference of Charities and Correction. School and Society 1 (1915):901–11. | ||

Geneiveve K, Bixler RW. The professional status of nursing. Am J Nurs. 1945;45:730–735. | ||

Cruess SR, Cruess RL. Professionalism must be taught. BMJ. 1997;315(7123):1674–1677. | ||

Swick H. Toward a normative definition of medical professionalism. Acad Med. 2000;75(6):612–616. | ||

Steinert Y, Cruess S, Cruess R, Snell L. Faculty development for teaching and evaluating professionalism: from programme design to curriculum change. Med Educ. 2005;39(2):127–136. | ||

Bixler GK, Bixler RW. The professional status of nursing. Can Nurse. 1946;42:35–43. | ||

Paramedic Portfolio and Scenario Based Exam. 2016; Available from: https://www.nremt.org/rwd/public/document/paramedic-portfolio. Accessed October 15, 2016. | ||

Epstein RM, Hundert EM. Defining and assessing professional competence. JAMA. 2002;287(2):226–235. | ||

Goldie J. Assessment of professionalism: a consolidation of current thinking. Med Teach. 2013;35(2):e952–e956. | ||

Traub ER, Glenn RL. Understanding reliability. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice. 1991;10(1):37–45. | ||

Papadakis MA, Loeser H, Healy K. Early detection and evaluation of professionalism deficiencies in medical students: one school’s approach. Acad Med. 2001;76(11):1100–1106. | ||

De Haes JC, Oort FJ, Hulsman RL. Summative assessment of medical students’ communication skills and professional attitudes through observation in clinical practice. Med Teach. 2005;27(7):583–589. | ||

Weis D, Schank MJ. An instrument to measure professional nursing values. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2000;32(2):201–204. | ||

Wynd CA. Current factors contributing to professionalism in nursing. J Prof Nurs. 2003;19(5):251–261. | ||

Kelley KA, Stanke LD, Rabi SM, Kuba SE, Janke KK. Cross-validation of an instrument for measuring professionalism behaviors. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(9):179. | ||

STN021 Teaching Faculty Standard-V1. www.phecc.ie: Pre-Hospital Emergency Care Council 2015:17–19. | ||

National Guidelines for Educating EMS Instructors. In: Transportation Do, ed. nhtsa.gov: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2002. | ||

Canada PAo. National Occupational Competency Profile for Paramedics. Additional Information for Education Programs. Available from: http://paramedic.ca/: Paramedic Association of Canada; 2011:15–17. | ||

Standards of proficiency. Paramdics. www.hcpc-uk.org: Health and Care Professions Council; 2014. Accessed October 15, 2016. | ||

Australasian Competency Standards for paramedics. Ballarat, VIC: Paramedics Australasia; 2011:11. | ||

Walt S, Margolis G, Paris P, Roth R. National Standard Curriculum. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 1998. | ||

Programs CoAoAHE. Standards and Guidelines for the Accreditation of Educational Programs in the Emergency Medical Services Professions. http://coaemsp.org/: Commission on Accreditation of Allied Health Education Programs; 2015:4, 6. | ||

Professions CoAoEPftEMS. CoAEMSP Interpretations of the CAAHEP 2015 Standards and Guidelines. For the Accreditation of Educational Programs in the EMS Professions. www.coaemsp.org Commission on Accreditation of Allied Health Education Programs; 2016. Accessed October 15, 2016. | ||

Appendix VI - Rubric Affective Domain Tool. In: Transportation USDo, ed. https://one.nhtsa.gov: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2002. Accessed October 15, 2016. | ||

College of paramedics-leading the development of the paramedic profession. The Exchange Express Park Bristol Road Bridgwater: College of Paramedics; 2014:100. | ||

Paramedic Continue to Hold Community Trust [press release]. Available from: www.paramedics.org.au2013. Accessed October 15, 2016. | ||

Paramedic Registration: Frequently Asked Questions; 2015. Available from: www.paramedics.org.au. Accessed October 15, 2016. | ||

Professionalism in healthcare professionals. Park House 184 Kennington Park Road London SE11 4BU: Health and Care Professions Council;2014. | ||

Standards and Guidelines for the Accreditation of Educational Programs in the Emergency Medical Services Professions. II. Program Goals. http://coaemsp.org/Standards.htm2015. | ||

Cizek GJB, Michael B. Standard Setting: A guide to establishing and evaluating performance standards for test. 2455 Teller Road, Thousand Oaks, CA 91320.: Sage Publications, Inc.; 2007. | ||

Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing. 1430 K St., NW, Suite 1200, Washington, DC, 20005: American Educational Research Assoication; 2014. | ||

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Social Research Methodology. 2005;8(1):19–32. | ||

James B, Lindstrom J. Construct validity of the professional behavior evaluation instrument from the National Standard Paramedic Curriculum. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2004;8(4):434–435. | ||

Brown WE Jr., Margolis G, Levine R. Peer evaluation of the professional behaviors of emergency medical technicians. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2004;20(2):107–114. | ||

Burford B, Morrow G, Rothwell C, Carter M, Illing J. Professionalism education should reflect reality: findings from three health professions. Med Educ. 2014;48(4):361–374. | ||

Birden H, Glass N, Wilson I, Harrison M, Usherwood T, Nass D. Teaching professionalism in medical education: a Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) systematic review. BEME Guide No. 25. Med Teach. 2013;35(7):e1252–e1266. | ||

Burford B, Carter M, Morrow G, Rothwell C, Illing J, McLachlan J. Professionalism and conscientiousness in healthcare professionals. Durham University School of Medicine and Health; April 21, 2011. | ||

Berk RA. A consumer’s guide to setting performance standards on criterion-referenced tests. Rev Educ Res. 1986;56(1):137–172. | ||

Stiggins RJ. Design and Development of Performance Assessments. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice 1987:33–42. | ||

Socha A, Cooper CA, McCord DM. Confirmatory factor analysis of the M5–50: an implementation of the International Personality Item Pool item set. Psychol Assess. 2010;22(1):43–49. | ||

Page D, Bowen LM, Stanke L. Increased Neuroticism is Associated with poor professional behavior during paramedic students field internships. National EMS Educators Symposium 2014. | ||

Page D, Bowen LM, Stanke L, Williams B. Empathy Levels of Students Entering US Paramedic Education Programs. National EMS Educators Symposium 2015. | ||

Hojat M, Louis DZ, Markham FW, Wender R, Rabinowitz C, Gonnella JS. Physicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. Acad Med. 2011;86(3):359–364. | ||

Yu J, Kirk M. Evaluation of empathy measurement tools in nursing: systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(9):1790–1806. | ||

Hemmerdinger JM, Stoddart SD, Lilford RJ. A systematic review of test of empathy in medicine. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7:24. | ||

Stobo J. Project Professionalism. Promoting Excellence in Health Care. 510 Walnut Street, Suite 1700, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 19106-3699: American Board of Internal Medicine. | ||

Robins LS, Braddock CH, Fryer-Edwards KA. Using the American Board of Internal Medicine’s ‘‘Elements of Professionalism’’ for undergraduate ethics education. Acad Med. 2002;77(6):523–531. | ||

A Consumer’s Guide to Setting Performance Standards on Criterion-Referenced Tests Author(s): Ronald A. Berk Source: Review of Educational Research, Vol. 56, No. 1 (Spring, 1986), pp. 137-172 Published by: American Educational Research Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1170289. Accessed October 16, 2016. | ||

Hambleton RK, Jones RW. Comparison of Classical Test Theory and Item Response Theory and Their Applications to Test Development. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice. 1993;12(3):38–47. | ||

Streiner DL, Geoffrey RN, Cairney J. Health Measurement Scales. A practical Guide to Their Development and Use. Fifth ed. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America: Oxford University Press; 2015. | ||

Burford B, Carter M, Morrow G, Rothwell C, Illing J, McLachlan J. Professionalism and conscientiousness in healthcare professionals. Durham University School of Medicine and Health; April 21, 2011. Available from: http://www.hcpc-uk.org/assets/documents/1000361BProfessionalismandconscientiousnessinhealthcareprofessionals-progressreportS2.pdf. Accessed September 26, 2017. | ||

Burford B, Carter M, Morrow G, Rothwell C, McLachlan J, Illing J. Development of a questionnaire to explore professionalism as a multi-dimensional construct. Professionalism and Conscientiousness in Healthcare Professionals – Study 2. Interim report for the HCPC. 2013. Available from: http://www.hpc-uk.org/assets/documents/10005038Measuringprofessionalismasamulti-dimensionalconstruct.pdf. Accessed October 2, 2017. |

Supplementary materials

| Table S1 A keyword search Abbreviations: EMS, Emergency Medical Services; EMT, Emergency Medical Technician; tw, text word; $.tw, wild card text word. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.