Back to Journals » Risk Management and Healthcare Policy » Volume 15

Prevalence, Perception, and Practice, and Attitudes Towards Self-Medication Among Undergraduate Medical Students of Najran University, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study

Authors Al-Qahtani AM , Shaikh IA , Shaikh MAK , Mannasaheb BA , Al-Qahtani FS

Received 5 November 2021

Accepted for publication 23 January 2022

Published 16 February 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 257—276

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S346998

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Jongwha Chang

Awad Mohammed Al-Qahtani,1 Ibrahim Ahmed Shaikh,2 Mohammed Ashique K Shaikh,3 Basheerahmed Abdulaziz Mannasaheb,4 Faisal Saeed Al-Qahtani5

1Department of Family and Community Medicine, College of Medicine, Najran University, Najran, Saudi Arabia; 2Department of Pharmacology, College of Pharmacy, Najran University, Najran, Saudi Arabia; 3Pharmacy Services Division, Najran University Hospital, Najran, Saudi Arabia; 4Department of Pharmacy Practice, College of Pharmacy, AlMaarefa University, Riyadh, 13713, Saudi Arabia; 5Department of Family and Community Medicine, College of Medicine, King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence: Awad Mohammed Al-Qahtani, Department of Family and Community Medicine, College of Medicine, Najran University, Najran, Saudi Arabia, Tel +966 530540450, Email [email protected]

Background: Self-medication (SM) is a customary practice around the globe. Appropriate SM comes with many advantages, yet irrational SM is a concern and could lead to adverse drug events and poor health outcomes.

Methods: This college-based cross-sectional study was carried out from January to March 2021 among Najran University undergraduate medical students to investigate the prevalence and practice of, and attitudes towards SM. Data were collected using a bilingual self-administered online questionnaire, which was categorized into sections, such as socio-demographic details, attitude towards SM, and practice of SM during the last six months, along with students’ opinions and suggestions regarding SM. The three-item scale was used to assess the students’ attitude. IBM SPSS was used to perform the cross-tabulation, chi-squared test, and binary logistic regression.

Results: Overall, 205 undergraduate medical students (58.6%) responded to the survey. The overall prevalence of SM was 60%, of which 25% used antibiotics as SM drugs. Headache (65.9%), fever (30.2%), cold/flu (31.2%), and gastric acidity (28.3%) were common illnesses for which SM was sought, using analgesics and NSAIDs (52.7%), antipyretics (13.7%), and antacid (12.7%) medications. Among the reasons for SM, the illness being minor and quick relief were frequently reported. To rationalize and improve the practice of SM, about half (48.3%) of the students suggested spreading awareness and education regarding the implications of SM and dispensing the medications with prescriptions (46.8%).

Conclusion: Overall, the attitude towards SM was satisfactory. The prevalence of SM during the last six months was 60%, and antibiotics were used by 25% of students. A significant negative correlation was observed between attitudes towards and practice of SM. Although medical students of Najran University displayed responsible behavior towards SM, efforts should be made to educate them about the adverse consequences of SM, especially with antibiotics.

Keywords: self-medication, students, practice, prevalence, Saudi Arabia

Introduction

Self-medication (SM) is the selection and utilization of medicines by people on their own to treat self-diagnosed illnesses or symptoms or the intermittent or continuous use of a prescribed drug for chronic or acute diseases or symptoms. SM is a part of self-care and a common practice worldwide.1–3 The prevalence of SM is higher in developing countries and is on the rise globally. SM is common in countries where it is easier to purchase prescription drugs without prescriptions and where the laws and regulations governing pharmacy practice are not followed under the pertinent guidelines.3–5

SM, when carried out responsibly, has many potential benefits: it saves time, increases access to effective treatment, is cost-effective when professional health services are relatively expensive and not readily available, reduces the frequency of visits to a physician, alleviates the burden on healthcare services, helps individuals in need of critical treatment to get appointments, increases patient confidence in treating minor illnesses, reduces absenteeism and increases workplace productivity of the population, and reduces costs to third-party payers such as governments and insurance companies.1,2,6,7

Nevertheless, inappropriate SM poses several potential risks, such as incorrect diagnosis, masking of signs and symptoms of the underlying illness, underdosing or overdosing, delay in seeking medical care, adverse drug effects, interactions with other concurrent medications or food, drug dependence, misuse, and antimicrobial resistance, all leading to wastage of resources.1,6–11

From the public health perspective, it should also be emphasized that irresponsible SM activities result in high healthcare costs, especially with the cost of adverse drug reactions and drug interactions suggesting a real economic burden. Inadequate healthcare facilities, long distances to the available healthcare facilities and, on the other hand, the easy availability of over-the-counter (OTC) drugs in the pharmacies are a few of the reasons for SM. Other reasons for SM can be mild illnesses, shortage of time for visiting the hospitals or clinics, the busy schedule of physicians resulting in unavailability of appointments, and physicians’ fees.12,13 Moreover, easy access to information about drugs on medical websites, in media advertisements, on social media, and in magazines promotes and encourages SM.12–14

However, in Saudi Arabia, physicians’ fees should not be a cause for SM as healthcare is entirely free for Saudi nationals and expatriates working as government employees. A range of socio-demographic factors, including but not limited to age, race, sex, educational and economic status, and residence, influences the practice of SM. Similarly, other factors leading to SM practice are previous experience, occupation, lack of healthcare facilities, lack of time, and low income.15

SM may appear to be a good idea at first, but one must consider the risks of such uninformed behavior. SM can result in allergy, drug addiction and interactions, habituation, disease worsening, wrong diagnosis and dose, disabilities, and sometimes even death.6 Surveillance systems, a collaboration between patients, physicians, and pharmacists, and providing educational information on safe SM to all parties involved are proposed techniques for optimizing the benefits and mitigating the risks of SM.6

The emergence of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in 2020 has significantly influenced the practice of SM and consequently increased the sales of OTC drugs. The OTC pharmaceuticals market was worth more than $151 billion in 2020, and it is expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of more than 5% to reach $209 billion between 2021 and 2027.16,17

According to recent studies, SM is frequent among people in the Middle East, leading to the misuse of medications.18,19 Several regional types of research have concentrated on SM behavior among students in universities, recognizing the rise and significant practice of SM in this category, and also recognizing critical indicators such as lifestyle, easy access to and availability of prescription medicines, thorough knowledge, advertising, and a good education.19–25 The common sources of medications for self-use were leftover prescription drugs, OTC medications obtained through pharmacies and some hypermarkets, borrowing of medications from family or friends, or purchase through online platforms.19

The education of medical and health sciences students emphasizes the sensible use of medicine and the consequences of irrational use. Because of their future medical choices and understanding of medications, SM among healthcare students is likely. Although many students regard SM as a time-saving, simple, and successful method, it comes with many risks. Numerous national and international studies have focused on SM practice among students, and especially healthcare students. This study was undertaken to determine the attitudes and SM patterns among undergraduate medical students in Najran University, Najran, Saudi Arabia. In addition, the study outcomes would be useful in incorporating some key topics related to the adverse consequences of SM and conducting awareness campaigns.

Methodology

Study Design and Population

This college-based cross-sectional study was carried out to investigate the prevalence of SM, attitudes, and factors influencing the practice of SM among undergraduate medical students of Najran University (NU), Saudi Arabia. The study was carried out from 15th January 2021 to 15th March 2021. Students from other colleges and universities, and those who refused to participate were excluded.

Study Instrument

A substantial literature review of similar studies5,12,13,19 was conducted. The questions from these studies were first collected, categorized, reshaped, and then translated into the Arabic language by an independent professional translator, and then back-translated to English through another professional translator to ensure their similarity. The study tool was validated for its content by three experts, one epidemiologist (Master’s in community health, eight years’ experience), one community pharmacist (Master’s in pharmacy, eight years’ experience), and one general physician (MBBS, MD, ten years’ experience). Following content validation, a pilot study was conducted on 10 students (five male and five female students) to test the face validity. The questionnaire was modified according to the feedback of the pilot study participants. The respondents of the pilot study were excluded from the final sample. The reliability of the study tool was calculated by Cronbach’s alpha-factor (0.69) and found to be satisfactory. Incomplete and repeat responses were excluded from the data analyses. The questionnaire was displayed online in Arabic and English (bilingual), using a Google form, to the medical students of NU through emails, WhatsApp, and other platforms. The questionnaire was categorized as follows: Section 1, socio-demographic details including age, gender, study level, parents’ qualification and working profession, siblings and children, marital and smoking status, etc; Section 2, attitude towards SM; and Section 3, practice of SM during the last six months, along with students’ opinions and suggestions regarding SM. Participation was voluntary; hence, we included accept/reject options at the beginning of questionnaires and an informed consent form elucidating the purpose of the study.

Sampling Method and Sample Size

Approximately 350 students are registered in the Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery program at the College of Medicine, Najran University, Saudi Arabia. The sample size was calculated using the Raosoft sample size calculator (Raosoft, Inc, Seattle, WA) by assuming a 95% confidence level, 5% margin of error, and precision level of 50%, and found to be 184. A simple random sampling technique was used to collect the data. We aimed to collect a larger sample size to ensure more representative data and anticipate a few incomplete and repeat responses; we collected a larger sample size of 205.

Data Collection

The students’ attitude towards SM was investigated using three statements, namely: A1, Self-medication is a part of self-care; A2, Self-medication without proper knowledge is harmful; and A3, Self-medication is not advisable for a prolonged period. Each statement was given three options: Yes, Maybe, and No. Students’ SM practice was measured using questions, including: Did you practice SM during the last six months?, Did you practice SM using antibiotics?, Do you check the expiry date before practicing SM?, and questions on the frequency of SM, source of drug information, class and names of medications, type of illness, and reasons influencing SM practice. Students’ opinions and suggestions to improve the appropriate SM, and to recommend family and friends to commence SM, were evaluated.

Ethical Statement

The institutional review board of Najran University approved this study (ref. no: NU.2020.03-EC). The research goals and procedures were described to the participants at the beginning of the online questionnaire along with the informed consent form, and informed consent was obtained from all participants. The participants were also informed that participation was voluntary and that the gathered information would be treated confidentially. The investigation was carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical Analysis

The collected data were subjected to preliminary checks to evaluate their completeness. The descriptive statistics were summarized by measuring frequency, percentage, and standard deviation. The chi-squared test was carried out using cross-tabulation to determine the factors associated with SM practice. Pearson’s correlation analysis was undertaken to examine the linear relationship between components of attitude and SM practice. A P-value of ≤0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 21.

Results

Demographic Details

As shown in Table 1, a total of 205 medical students completed the survey, giving a response rate of 58.6%, which was submitted for data analysis. The majority of the students were male (68.3%), non-smokers (64.9%), aged 20–25 years (62.9%), unmarried (78.5%), living with family (89.8%), from internship level (33.2%), and with a father whose profession was non-medical (82%). Other demographic details are presented in Table 1.

|  |  |

Table 1 Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Study Participants |

Students’ Attitude Towards Self-Medication

As shown in Table 2, students’ attitude towards SM was evaluated using three statements; namely, A1, A2 and A3. Factors that significantly impacted attitude A1 were age, study level, number of siblings and children, health status, distance to healthcare service, parents’ qualification and profession, and transport facility. Similarly, factors that influenced attitude A2 were area of residence, study level, family income, number of siblings and children, marital status, smoking and health status, distance to a healthcare facility, mother’s education and profession, and availability of transport facility. Likewise, attitude A3 was influenced by gender, age, area of residence, study level, family income, number of siblings, residential and smoking status, distance to a healthcare facility, mother’s qualification, and availability of transport facilities, as shown in Table 2.

|  |  |  |

Table 2 Attitude Towards Self-Medication Among Medical Students of NU (n=205) |

Practice of Self-Medication

Sixty percent (60%) of students had practiced SM during the last six months; 25% had self-medicated with antibiotics. The antibiotic course had been completed by all. Almost half of the students (42.92%) had practiced SM 1–3 times during the last six months. More than two-thirds of students declared that they check the expiry date of medications before using them for self-care.

Source of Information About Drugs Used for Self-Medication

Table 3 illustrates the various sources which the students utilized to obtain information about drugs. Almost half of the students relied on previous prescriptions (43.4%) and pharmacists (44.9%) to obtain drug information. Drug advertisements had the most negligible impact as a source of information (4.4%).

|

Table 3 Self-Medication Practice Among Medical Students of NU |

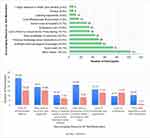

Medications Used to Practice Self-Medication

As shown in Figure 1, the typical classes of drugs used to practice SM during the last six months were analgesics and NSAIDs (52.7%), followed by antipyretics (13.7%) and antacids (12.7%). Dietary supplements were the least (3.9%) used drugs to practice SM (Figure 1). The drugs mentioned as others include contraceptives, bronchodilators, antiviral, antifungal, and herbal products. Participants also mentioned the specific type of drug used; the highest among them were paracetamol (20%), diclofenac (1%), ibuprofen (1%), pantoprazole (5.4%), amoxicillin (3.9%), hyoscine (2.9%), vitamin C (2%), and domperidone (1.5%).

|

Figure 1 Medications used during the last six months for self-medication. |

Illnesses for Which Self-Medication is Practiced

As shown in Figure 2, headache (65.9%), cold and flu (31.2%), fever (30.2%), and gastric acidity and ulcer (28.3%) were the most common illnesses for which SM was practiced by the students. The least common illnesses were musculoskeletal pain (5.9%) and menstrual problems (6.3%).

|

Figure 2 Illnesses for which self-medication was practiced. |

Reasons Influencing Self-Medication Practice

As shown in Figure 3, we assessed the reasons which encourage and discourage the practice of SM. Figure 3 shows the main reasons that influenced the practice of SM among medical students during the last six months. The most common reasons for choosing SM practice were the minor nature of the illness (49.3%), quick relief (35.1%), good pharmacological knowledge (25.9%), and previous information about drugs (23.4%). Privacy (2.9%), a longer distance to a healthcare facility (2.9%), and learning opportunities (4.9%) were the least common reasons. In contrast, 40% of students who did not practice SM were asked to mention the reasons. The most common discouraging factors towards SM practice were fear of adverse effects, worsening of the condition, misdiagnosis, and lack of knowledge.

|

Figure 3 Reasons influencing the practice of self-medication. |

Students’ Opinions and Suggestions Regarding Self-Medication

As depicted in Figure 4, the students have shared their viewpoints, which could help to rationalize and improve the practice of SM. About half (48.3%) of students suggested spreading awareness and education regarding the implications of SM and dispensing the medications with prescriptions (46.8%). Unfortunately, about 10.2% of students stated that they had no suggestions. Interestingly, 83 students (40.5%) declared that they do not recommend SM practice to family and friends, whereas 36.6% mentioned that they recommend SM practice. About 34% of students wished to either continue or start SM practice. However, most (40%) of the students were not sure about commencing new SM practice (Figure 4).

|

Figure 4 Students’ opinions and suggestions regarding self-medication. |

Factors Influencing Self-Medication Practice

As shown in Table 4, binary logistic analysis was performed to predict the factors influencing SM practice. The married students have a significantly (P=0.026) 2.13 times higher risk (OR: 2.131) of practicing SM than the single students. Students residing far from healthcare services have a significantly (P=0.046) 1.91 times higher risk (OR: 1.915) of adopting SM practice than those who live near. Students whose fathers work in the non-medical sector have a significantly (P=0.032) 2.3 times higher risk (OR: 2.391) of practicing SM than students whose fathers work in the medical sector. Students residing in urban areas have a significantly (P=0.001) 0.3 times higher (OR: 0.305) risk of practicing SM than students staying in rural areas. Gender, age, accommodation, and family earnings were not among the risk factors influencing SM practice. Further, Table 5 shows the results of logistic regression analysis conducted using statistically significant factors obtained from the bivariate analysis of influencing factors, such as marital status, area of residence, father’s profession, and distance to a healthcare facility. These four predictors accounted for 15% of the variation in the SM practice during the last six months (R2 change=0.15). The results indicate that unmarried students have significantly (P=0.04) 2 times higher likelihood (OR: 2.123, 95% CI 1.035–4.353) of practicing SM compared to married students. Likewise, students whose fathers work in medical sector have significant (P=0.023) 2.8 times higher probability of indulging into SM practice compared to their counterparts. Conversely, students who reside in rural areas have significantly (P=0.001) lower chances of practicing SM compared to students who stay in urban areas (Table 5).

|

Table 4 Factors Influencing Self-Medication Practice |

|

Table 5 Logistic Regression Analysis Identifying the Variables Significantly Associated with Self-Medication During the Last Six Months |

Correlation Between Attitudes and Self-Medication Practice

As shown in Table 6, we observed a non-significant negative correlation between the practice of SM and attitude 1 (Self-medication is a part of self-care). The practice of SM decreased non-significantly with an increase in the belief that SM is part of self-care (r=1.131, P=0.062). Likewise, a significant (P=0.001) negative correlation (r=−0.268**) was found between SM practice and attitude 2 (Self-medication without proper knowledge is harmful). Students who accept that SM without appropriate knowledge is hazardous show a low practice of SM. Similarly, we noticed a significant (P=0.001) negative correlation (r=−0.243**) among SM practice and attitude 3 (Self-medication is not advisable for a prolonged period). Students who feel that prolonged SM is not advised indicated a low practice of SM.

|

Table 6 Pearson Correlations Between Attitude Components and Self-Medication Practice |

We noted significant positive correlations among different components of attitude. Students who accept that SM is a part of self-care strongly agree that SM without proper knowledge is harmful (r=0.402**, P=0.001) and that it’s not advised to practice SM for a prolonged period (r=0.148*,P=0.034). Comparably, participants who feel that SM without proper knowledge is harmful agree that it is not appropriate to practice SM for a prolonged time (r=0.576**, P=0.001).

Discussion

The World Health Organization (WHO) encourages and supports responsible SM for minor health issues that do not need medical consultation. Also, SM is a convenient and inexpensive replacement for treating the most common illnesses. Yet, inappropriate and irrational SM poses numerous health hazards, such as poor treatment outcome, masking of actual diagnoses, drug and food interactions, side effects, increased antimicrobial resistance, especially with antibiotics, and other endless health issues.

In our study, we observed that 60% of medical students had practiced SM during the last six months, which is lower compared to findings in students from King Khalid University, Abha (98.7%),23 AlQassim University (86.6%),24 and Jazan University (87%),21 Bangladeshi undergraduate pharmacy students (88%),13 and students from Zabol University of Medical Sciences, Iran (57%),26 and Kasturba Medical College, India (78.6%).12 In contrast, students from AlMaarefa University, Riyadh (55%),19 and Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University (26%) in Dammam, Saudi Arabia,20 demonstrated a lower prevalence of SM. We noticed that area of residence, marital status, father’s profession, and distance to a healthcare facility had a significant impact on the practice of SM; similar findings were noted among AlMaarefa students,19 where SM practice was low among students whose parents/family members were working in the health sector.

In our study, we observed that about one-fourth of students (25.36%) had used antibiotics for self-care, unlike findings from students of AlMaarefa University, Riyadh (12.4%), students of King Khalid University, Abha (22%),23 and Bangladeshi undergraduate pharmacy students (15.6%).13 In contrast, SM with antibiotics was higher among the students of Kasturba Medical College, India (39.3%),12 and residents of Saudi Arabia (34%).27 Interestingly, all of the students who used antibiotics for self-care completed the antibiotic course. This practice indicates that medical students of NU possess adequate information about antimicrobial resistance and the adverse outcomes of inappropriate antibiotic use. Yet, irrational use of antibiotics could be overlooked. The students stated headache, cold and flu, fever, and gastric acidity and ulcer as the common illnesses for which SM is practiced; similar findings were noted in previously published studies.12,13,19,21,24,26,28 The typical classes of drugs used to practice SM during the last six months were analgesics and NSAIDs (52.7%), antipyretics (13.7%), and antacids (12.7%), which corroborates with other studies within Saudi Arabia.19,20,23 Participants also mentioned the specific type of drug used; the highest among them were paracetamol (20%), pantoprazole (5.4%), amoxicillin (3.9%), hyoscine (2.9%), vitamin C (2%), and domperidone (1.5%). The reasons which encouraged the students to practice SM were the minor nature of the illness (49.3%), quick relief (35.1%), good pharmacological knowledge (25.9%), and previous information about the drugs (23.4%); similar findings were reported in earlier regional19,20,23 and international studies.12,29,30 In contrast, students from other healthcare programs have also reported lack of time (59%) and knowledge about treatment as the main reasons for SM practice.31 About 40% of students had not practiced SM during the last six months, and the reasons mentioned were fear of adverse effects, worsening of the condition, and misdiagnosis; similar findings have been reported among students from the city of Mansoura, Egypt.28 This attitude indicates that medical students of NU are aware of appropriate SM and its implications. The students referred to previous prescriptions (43.4%), pharmacists (44.9%), and academic knowledge (38.5%) as prime sources of drug information to practice SM. Being medical students, they referred to pharmacists to obtain the drug information, which indicates their positive attitude towards the pharmacists’ role. These findings are in line with previous studies.13,19,23,26,28,30 In the present study, about half of the students (42.9%) reported that they had practiced SM one to three times during the last six months, which is less than once a month. This is comparable with findings from students of AlMaarefa University, Riyadh.

The participating students made some suggestions, which would be helpful to improve and rationalize the practice of SM. About half (48.3%) of the students suggested spreading awareness and education regarding the implications of SM, which would help to restrict the inappropriate practice of SM. These findings are lower than the recommendations proposed by students of AlMaarefa University, Riyadh (87.6%). About 47% of the students suggest that dispensing the medications with prescriptions would be another great option to limit SM practice, similarly to the students of Kasturba Medical College, India (39.3%).12 The majority of students (40%) stated that they do not recommend their loved ones (family and friends) to practice SM, whereas a similar percentage of students said that they were not sure about either continuing or starting the practice of SM themselves. These observations parallel the findings among students of Kasturba Medical College, India,12 where 68% of students did not recommend SM practice to their family and friends.

Overall, the attitude towards SM among medical students of NU is satisfactory. In our study, we observed a significant positive correlation among the different domains of attitude, whereas a significant negative correlation was observed between attitudes and the practice of SM. This clearly indicates that as the students’ level of attitude towards SM increases, the practice of SM decreases significantly.

Limitations and Recommendations

Although the required sample size was achieved, 40% of students did not participate in the study. Medical students from all study levels participated in this research. The outcomes of this study are from medical students, most of them in their senior years, and hence the results cannot be generalized to students of other programs or the general public. Since the SM practice domain was embedded with recollect medication-related questions, the time frame was set to the last six months to avoid recall bias. Considering the low level of question understanding among initial study-year students, the questionnaire was disseminated bilingually (in English and Arabic) to improve their understanding of the questions. It is recommended that data should be collected from students who did not participate in our study because of their busy schedules. We recommend expanding this study to other colleges of NU, including the College of Pharmacy, Dentistry, and Applied Sciences, and comparing their findings with those of the medical students. SM is affordable and has many advantages, but spreading awareness about responsible and rational SM and highlighting the negative impacts of inappropriate and unsupervised SM is critically important.

Conclusion

Overall, the medical students displayed a good positive attitude towards SM. The prevalence of SM practice was 60%, with a major frequency of one to three times during the last six months, and antibiotics were used for self-care by 25% of students, yet they completed the course of antibiotic treatment. A significant negative correlation was observed between attitudes towards and practice of SM. Although medical students of Najran University showed responsible behavior towards SM and practiced SM for minor illnesses with OTC drugs, efforts should be made to educate them about the adverse consequences of SM, especially with antibiotics, as they will become the healthcare professionals of the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Najran University, Najran, KSA, for their support in completing this study. The authors also thank AlMaarefa University for supporting this work via the Researchers Supporting Program (TUMA-Project-2021-36), AlMaarefa University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest for this work.

References

1. World Health Organization. Guidelines for the regulatory assessment of medicinal products for use in self-medication; 2000. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/66154. Accessed January 25, 2022.

2. World Health Organization. The role of the pharmacist in self-care and self-medication: report of the 4th WHO consultative group on the role of the pharmacist, the Hague, the Netherlands, 26–28 August 1998; 1998. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/65860. Accessed January 25, 2022.

3. World Health Organization. The benefits and risks of self-medication: general policy issues. WHO drug information 2000; 14(1): 1–2; 2000 [cited Oct 22, 2021]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/57617.

4. Sawalha AF. A descriptive study of self-medication practices among Palestinian medical and nonmedical university students. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2008;4(2):164–172. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2007.04.004

5. Alam N, Saffoon N, Uddin R. Self-medication among medical and pharmacy students in Bangladesh. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8(1):763. doi:10.1186/s13104-015-1737-0

6. Hughes CM, McElnay JC, Fleming GF. Benefits and risks of self medication. Drug Saf. 2001;24(14):1027–1037. doi:10.2165/00002018-200124140-00002

7. Brass EP. Changing the status of drugs from prescription to over-the-counter availability. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(11):810–816. doi:10.1056/NEJMra011080

8. Ruiz ME. Risks of self-medication practices. Curr Drug Saf. 2010;5(4):315–323. doi:10.2174/157488610792245966

9. Ferris DG, Nyirjesy P, Sobel JD, Soper D, Pavletic A, Litaker MS. Over-the-counter antifungal drug misuse associated with patient-diagnosed vulvovaginal candidiasis. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99(3):419–425. doi:10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01759-8

10. Foley M, Harris R, Rich E, et al. The availability of over-the-counter codeine medicines across the European Union. Public Health. 2015;129(11):1465–1470. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2015.06.014

11. Calabresi P, Cupini LM. Medication-overuse headache: similarities with drug addiction. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26(2):62–68. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2004.12.008

12. Kumar N, Kanchan T, Unnikrishnan B, et al. Perceptions and practices of self-medication among medical students in coastal South India. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e72247. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0072247

13. Seam M, Bhatta R, Saha B, et al. Assessing the perceptions and practice of self-medication among Bangladeshi undergraduate pharmacy students. Pharmacy. 2018;6(1):6. doi:10.3390/pharmacy6010006

14. Alyahya K, AlRaddadi K, Barakeh R, AlRefaie S, AlYahya L, Adosary M. Determinants of self-medication among undergraduate students at King Saud University: knowledge, attitude and practice. J Health Spec. 2017;5(2):95. doi:10.4103/2468-6360.205078

15. Kassie AD, Bifftu BB, Mekonnen HS. Self-medication practice and associated factors among adult household members in Meket district, Northeast Ethiopia, 2017. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2018;19(1). doi:10.1186/s40360-018-0205-6

16. Ugalmugle S, Swain R. Over the counter (OTC) drugs market size by product (analgesics, cold, cough & flu products, weight loss products, gastrointestinal products, skin products, minerals and vitamin supplements, sleeping aids, ophthalmic products), COVID-19 impact analysis, regional outlook, application potential, price trends, competitive market share & forecast, 2021 – 2027. Global Market Insights, Inc; 2021.

17. Montastruc J-L, Bondon-Guitton E, Abadie D, et al. Pharmacovigilance, risks and adverse effects of self-medication. Therapie. 2016;71(2):257–262. doi:10.1016/j.therap.2016.02.012

18. Alhomoud F, Aljamea Z, Almahasnah R, Alkhalifah K, Basalelah L, Alhomoud FK. Self-medication and self-prescription with antibiotics in the Middle East-do they really happen? A systematic review of the prevalence, possible reasons, and outcomes. Int J Infect Dis. 2017;57:3–12. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2017.01.014

19. Mannasaheb BA, Al-Yamani MJ, Alajlan SA, et al. Knowledge, attitude, practices and viewpoints of undergraduate university students towards self-medication: an institution-based study in Riyadh. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(16):8545. doi:10.3390/ijerph18168545

20. Albusalih FA, Naqvi AA, Ahmad R, Ahmad N. Prevalence of self-medication among students of pharmacy and medicine colleges of a public sector university in Dammam city, Saudi Arabia. Pharmacy. 2017;5(3):51. doi:10.3390/pharmacy5030051

21. Albasheer OB, Mahfouz MS, Masmali BM, et al. Self-medication practice among undergraduate medical students of a Saudi tertiary institution. Trop J Pharm Res. 2016;15(10):2253. doi:10.4314/tjpr.v15i10.26

22. Mustafa OM, Rohra DK. Patterns and determinants of self-medication among university students in Saudi Arabia. J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2017;8(3):177–185. doi:10.1111/jphs.12178

23. Alshahrani SM, Alavudeen SS, Alakhali KM, Al-Worafi YM, Bahamdan AK, Vigneshwaran E. Self-medication among King khalid University students, Saudi Arabia. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2019;12:243–249. doi:10.2147/RMHP.S230257

24. Al-Worafi YA, Long C, Saeed M, Alkhoshaiban A. Perception of self-medication among university students in Saudi Arabia. Arch Pharm Pract. 2014;5(4):149. doi:10.4103/2045-080X.142049

25. Flaiti MA, Badi KA, Hakami WO, Khan SA. Evaluation of self-medication practices in acute diseases among university students in Oman. J Acute Dis. 2014;3(3):249–252. doi:10.1016/S2221-6189(14)60056-1

26. Hashemzaei M, Afshari M, Koohkan Z, Bazi A, Rezaee R, Tabrizian K. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of pharmacy and medical students regarding self-medication, a study in zabol university of medical sciences; Sistan and Baluchestan province in south-east of Iran. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):49. doi:10.1186/s12909-020-02374-0

27. Alghadeer S, Aljuaydi K, Babelghaith S, Alhammad A, Alarifi MN. Self-medication with antibiotics in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm J. 2018;26(5):719–724. doi:10.1016/j.jsps.2018.02.018

28. Helal RM, Abou-ElWafa HS. Self-medication in university students from the city of Mansoura, Egypt. J Environ Public Health. 2017;2017:1–7. doi:10.1155/2017/9145193

29. Sawalha AF. Assessment of self-medication practice among university students in Palestine: therapeutic and toxicity implications. IUG J Nat Eng Stud. 2015;15(2): 67–82.

30. Islam B, Hossain MA. Prevalence of self medication practice among students of a medical college. Bang Med J Khulna. 2019;52:21–24. doi:10.3329/bmjk.v52i1-2.46144

31. Faqihi AHMA, Sayed SF. Self-medication practice with analgesics (NSAIDs and acetaminophen), and antibiotics among nursing undergraduates in university college farasan campus, Jazan University, KSA. Ann Pharm Fr. 2021;79(3):275–285. doi:10.1016/j.pharma.2020.10.012

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.