Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 12

Prevalence and correlates of past 12-month suicide attempt among in-school adolescents in Guatemala

Received 17 April 2019

Accepted for publication 10 June 2019

Published 9 July 2019 Volume 2019:12 Pages 523—529

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S212648

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Supa Pengpid1,2 Karl Peltzer2

1ASEAN Institute for Health Development, Mahidol University, Salaya, Phutthamonthon, Nakhonpathom, Thailand; 2Office of the Deputy Vice Chancellor, Research and Innovation, North West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

Background: The aim of this investigation was to estimate the prevalence of past 12-month suicide attempts and associated factors among in-school adolescents in Guatemala.

Methods: Cross-sectional data from the 2014 “Global School-based Health Survey (GSHS)” included 4,274 students (median age 14 years, interquartile range=2 years) that were representative of all middle school students in Guatemala.

Results: The prevalence of past 12-month suicide attempt was 16.6%, 12.2% among boys and 20.2% among girls. Among students with a suicide attempt in the past year, 52.8% had a suicide plan in the past year. In adjusted logistic regression analysis, male sex and loneliness were associated with past 12-month suicide attempt, and among boys, none of the variables, and among girls, loneliness and current alcohol use were associated with past 12-month suicide attempt.

Conclusion: A high prevalence and several specific factors associated with suicide attempt were identified which can help in guiding preventive strategies.

Keywords: suicidal attempt, demographic factors, internalizing problems, externalizing problems, Guatemala

Introduction

Suicide is a leading cause of death among adolescents.1 Suicide attempt has been identified as a major risk factor for suicide death.2 Suicide prevention activities among adolescents need to include the assessment of the prevalence and correlate of suicide attempts.3 There are limited data on the recent prevalence and its correlates of suicide attempts among adolescents in Guatemala, a small country located in Central America.4

A significant increase in suicide rates among adolescents (15–19 years) was found in Guatemala for both genders, among boys from 3.07 in 1990–1999 to 4.74 2000–2009, and among girls from 1.63 in 1990–1999 to 3.12 in 2000–2009.5 In a school survey among students (12–18 years) in southwest Trifinio region of Guatemala, 11.6% reported suicidal ideation.6 In the 2009 Guatemala “Global School-based Health Survey (GSHS)”, the prevalence of suicide attempt was 13.4% (10.4% among boys and 16.7% among girls).7 In a cross-sectional survey of suicide attempters (N=31) attending emerging care services in Santa Rosa in Guatemala, Mijangos et al4 found that 39% were adolescents (14–18 years old), and 71% had used poisoning with agrochemicals as a means of attempting suicide. In school-based surveys of students (12–18 years) from 40 low-income and middle-income countries, the “mean 12-month prevalence of suicide attempts was 17.2%”.7 In other countries in Central America, the past 12-month prevalence of suicide attempts among school-going adolescents was in Belize 13.3%, Costa Rica 8.5%, El Salvador 13.1% and Honduras 17.2%.7 In a local community study among youth in Nicaragua, the prevalence of past 12-month suicide attempt was 2.1% in males and 1.5% in females,8 and in another small study in Nicaragua among adolescents, the prevalence of past 12-month suicide plans or attempt was 10.1% among boys and 12.8% among girls.9

Factors associated with suicide attempts among adolescents may include sociodemographic variables, internalizing and externalizing problems. Sociodemographic factors include female sex,7,10 older age,7 and food insecurity or lower socioeconomic status.7,11 Internalizing problems may include, having no close friends,12 loneliness7,12,13 and anxiety.7,11,13,14

Externalizing problems may include, alcohol use,7,12,14,15 drug use,13–15 cannabis use,16 soft drink consumption,17 being bullied,7,12,18,19 exposure to interpersonal violence,10 being physically attacked,13,15 and in physical fight,15 sexual coitus20 and injury.21 Limited data exist on the prevalence and correlates of suicide attempts among adolescents in Guatemala. Consequently, this investigation aimed at examining the prevalence, sociodemographic, internalizing and externalizing problems associated with suicide attempts among in-school adolescents in Guatemala.

Methods

Sample and procedure

This analysis utilizes 2015 Guatemala “Global School-based Health Survey (GSHS)” cross-sectional data; more details and the dataset can be publicly accessed.22 The study used a two-stage cluster sampling strategy to produce a nationally representative sample of all students in “Primero (First), Segundo (Second), and Tercero basico (Basic third)” in Guatemala.23 Under the supervision of trained survey administrators, students completed a self-administered questionnaire in their language during classroom periods.23 The study proposal was approved by the Ministry of Education and a national ethics committee, and “necessary approvals and permission were obtained from the participating schools, parents and students before the survey was administered”.23

Measures

The study questionnaire used was from the GSHS24 and is shown in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Description of variables |

Data analysis

Data analysis was done with STATA software version 15.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA), taking the complex sampling design of the study into account. Data results were described with descriptive statistics. Logistic regression was used to estimate associations between independent variables and one or multiple suicide attempts in the past year, overall, and for boys and girls, separately. Missing cases were excluded from the analysis. To minimize type 1 error, a greater alpha level of 0.01 was used as cutoff for significance.

Results

Sample characteristics

The study sample consisted of 4,274 middle school students (median age 14 years, interquartile range=2 years) from Guatemala. The proportion of male students was 49.4% and that of female students 50.6%. The overall study response rate was 82%.21 Almost one in seven (15.0%) of the students reported sometimes, mostly or always experiencing hunger, 7.1% had no close friends, 8.9% felt lonely and 7.1% had anxiety. Further, 18.3% of the participants were current alcohol users, 4.1% current cannabis users, 3.4% had ever used amphetamine, 19.7% ever had sex, 28.0% consumed two or more soft drinks a day, 23.9% had been bullied in the past month, 23.9% had been attacked in the past year, 22.8% in a physical fight and 31.8% had sustained a serious injury in the past year. The prevalence of past 12-month suicide attempt was 16.6%, 12.2% among boys and 20.2% among girls. Among students with a suicide attempt in the past year, 52.8% had a suicide plan in the past year. Further sample characteristics are presented in Table 2.

|

Table 2 Descriptive statistics of independent variables and by suicidal attempt |

Associations with suicide attempt

In adjusted logistic regression analysis, male sex and loneliness were associated with past 12-month suicide attempt. In addition, in unadjusted analysis, sometimes, mostly or always experiencing hunger, having no close friends, anxiety, substance use (alcohol, cannabis and amphetamine) and interpersonal violence (bullying victimization, having been physically attacked, and in a physical fight) and injury was associated with past 12-month suicide attempt (see Table 3).

|

Table 3 Logistic regression for predictors of suicide attempts |

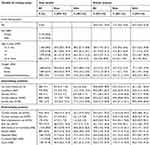

Associations with suicide attempt by sex

In adjusted logistic regression analysis, among boys, none of the variables and among girls loneliness and current alcohol use were associated with past 12-month suicide attempt. In addition, in unadjusted analysis, among boys, having no close friends, loneliness, anxiety, substance use (alcohol, cannabis and amphetamine) and interpersonal violence (bullying victimization and having been physically attacked) were associated with past 12-month suicide attempt. In unadjusted analysis among girls, in addition, current cannabis use, ever amphetamine use and in a physical fight were associated with past 12-month suicide attempt (see Table 4).

|

Table 4 Logistic regression for predictors of suicide attempts in boys and girls |

Discussion

The study aimed to examine for the first time the national prevalence of past 12-month suicide attempt and associated factors among school adolescents in Guatemala. The prevalence of past 12-month suicide attempt was 16.6%, 12.2% among boys and 20.2% among girls, which is an increase compared to the 2009 GSHS in Guatemala (overall 13.4%, 10.4% among boys and 16.7% among girls),7 higher than in Belize (13.3%), Costa Rica (8.5%), El Salvador (13.1%)7 and Nicaragua (<12%),8,9 but similar to Honduras (17.2%), and the mean prevalence from 40 low-income and middle-income countries (17.2%).7 Some of the country differences be may relate to social and cultural factors, which should be subject to future studies.

The study found that among those with a suicide attempt in the past 12 months, about half (52.7%) had a suicide plan in the past 12 months. This result is consistent with previous findings,7 and underlines the seriousness of the suicide attempts compared to impulsively implemented suicide attempts in this study.7 Considering that suicide plans are developed prior to suicide attempts, it will be important to identify suicide plans early in order to prevent suicide.7 In case of impulsive suicide attempts, it will be crucial to restrict access to means of attempting suicide in suicide prevention.7 This may turn out to be difficult, as many adolescents in Guatemala use fairly easy available agrochemicals (herbicides and organophosphates) as a means of attempting suicide.4

Consistent with previous research,7,10 this study found that the prevalence of suicide attempt was higher in girls than in boys. Such gender differences may be related to greater internalizing of emotional and behavioral problems among females than males (leading more likely to suicidal ideation and suicide attempts) and greater externalizing emotional and behavioral problems among males than females (leading more likely to suicide death).25 In this study, most internalizing problems were higher in girls than in boys, and most externalizing problems were higher in boys than girls. Some studies7 found that suicide attempts during adolescents increase with age, while this study did not find age differences. Contrary to previous findings that found an association between poor socioeconomic status or food insecurity,7,11 this study found only in unadjusted analysis such an association. This study reports an association between internalizing problems or psychosocial distress (loneliness, and in unadjusted analysis having no close friends and anxiety) and suicidal attempt. The link between psychosocial distress and suicide attempt has been established in previous studies.7,10,11,13,15,21

Consistent with previous research,7,12–16 this study found, among girls, an association between substance use (alcohol, and overall, in unadjusted analysis, current cannabis use and lifetime amphetamine use) and suicide attempts. The correlation between substance use, mental distress and suicide attempt may refer to a clustering of health risk behaviors. Consistent with a previous review,10 this study found female-specific risk factors (loneliness) but not male-specific risk factors for suicide attempt. These health risk behaviors identified may need to be targeted in health promotion intervention in a combined fashion, rather than addressing individual risk behaviors in preventing suicide attempts.

Study limitations

The cross-sectional study was limited to school-going youth and precludes causative conclusions and generalizations for all youth. The GSHS content was assessed by self-report, including suicidal behavior, internalizing and externalizing problems, and could lead to bias in reporting. Another limitation was that the GSHS in Guatemala did not assess rural-urban location of the study schools.

Conclusions

A high prevalence of suicide attempts was observed among school-going adolescents in Guatemala. Several factors were identified, among both boys and girls, loneliness, and among girls, alcohol use and ever amphetamine use, which should be targeted in health promotion school programs, so as to prevent suicide attempts among adolescents in Guatemala.

Acknowledgments

We thank the World Health Organization for making the data available for data analysis (https://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/gshs/guatemaladataset/en/), and the country coordinator from Guatemala (Olivia J. Brathwaite Dick) for the assistance in GSHS data collection.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. World Health Organization (WHO). Adolescent mental health; 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health.

2. Bilsen J. Suicide and youth: risk factors. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:540. eCollection 2018. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00540

3. Hawton K, Saunders KE, O’Connor RC. Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. Lancet. 2012;379(9834):2373–2382. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60322-5

4. Mijangos MDF, Coguox LNC, Morales MRS, Patino DC, Torres AR. Suicide attempt: sociodemographic/motivational description of case series in Santa Rosa, Guatemala. Int J Curr Adv Res. 2017;6(4):3474–3477. doi:10.24327/ijcar.2017.3477.0297

5. Kõlves K, De Leo D. Adolescent suicide rates between 1990 and 2009: analysis of age group 15-19 years worldwide. J Adolesc Health. 2016;58(1):69–77. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.09.014

6. Johnson RK, Lamb M, Anderson H, et al. The global school-based student health survey as a tool to guide adolescent health interventions in rural Guatemala. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):226. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-6539-1

7. Liu X, Huang Y, Liu Y. Prevalence, distribution, and associated factors of suicide attempts in young adolescents: school-based data from 40 low-income and middle-income countries. PLoS One. 2018:13(12):e0207823. eCollection 2018. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0207823.

8. Rodríguez AH, Caldera T, Kullgren G, Renberg ES. Suicidal expressions among young people in Nicaragua: a community-based study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41(9):692–697. doi:10.1007/s00127-006-0083-x

9. Medina CO, Jegannathan B, Dahlblom K, Kullgren G. Suicidal expressions among young people in Nicaragua and Cambodia: a cross-cultural study. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:28. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-12-28

10. Miranda-Mendizabal A, Castellví P, Parés-Badell O, et al. Gender differences in suicidal behavior in adolescents and young adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Int J Public Health. 2019;64(2):265–283. doi:10.1007/s00038-018-1196-1

11. Oppong Asante K, Kugbey N, Osafo J, Quarshie EN, Sarfo JO. The prevalence and correlates of suicidal behaviours (ideation, plan and attempt) among adolescents in senior high schools in Ghana. SSM Popul Health. 2017;3:427–434. eCollection 2017 Dec. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.05.005

12. Davaasambuu S, Batbaatar S, Witte S, et al. Suicidal plans and attempts among adolescents in Mongolia. Crisis. 2017;38(5):330–343. doi:10.1027/0227-5910/a000447

13. Randall JR, Doku D, Wilson ML, Peltzer K. Suicidal behaviour and related risk factors among school-aged youth in the Republic of Benin. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e88233. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088233

14. Carballo JJ, Llorente C, Kehrmann L, et al. Psychosocial risk factors for suicidality in children and adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019. doi:10.1007/s00787-018-01270-9

15. Sharma B, Nam EW, Kim HY, Kim JK. Factors associated with suicidal ideation and suicide attempt among school-going urban adolescents in Peru. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(11):14842–14856. doi:10.3390/ijerph121114842

16. Carvalho AF, Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, et al. Cannabis use and suicide attempts among 86,254 adolescentsaged 12-15 years from 21 low- and middle-income countries. Eur Psychiatry. 2019;56:8–13. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.10.006

17. Park DE, Kim JL, Cho J. Soft drink consumption and suicide attempts in adolescents: the Korean Youth Risk Behavior Web-Based Survey. J Prev Med. 2016;1(3):9. doi:10.21767/2572-5483.100009

18. Romo ML, Kelvin EA. Impact of bullying victimization on suicide and negative health behaviors among adolescents in Latin America. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2016;40(5):347–355.

19. Koyanagi A, Oh H, Carvalho AF, et al. Bullying victimization and suicide attempt among adolescents aged 12-15 years from 48 countries. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019:

20. Chin YR, Choi K. Suicide attempts and associated factors in male and female Korean adolescents a population-based cross-sectional survey. Community Ment Health J. 2015;51(7):862–866. doi:10.1007/s10597-015-9856-6

21. Shaikh MA, Lloyd J, Acquah E, Celedonia KLL, Wilson M. Suicide attempts and behavioral correlates among a nationally representative sample of school-attending adolescents in the Republic of Malawi. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):843. doi:10.1186/s12889-016-3509-8

22. World Health Organization (WHO). Global school-based student health survey (GSHS), 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/gshs/guatemaladataset/en/.

23. World Health Organization (WHO). Global school-based student health survey, Guatemala 2015 Fact sheet; 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/gshs/gshs_fs_guatemala_2015.pdf.

24. World Health Organization (WHO). Global school-based student health survey (GSHS). 2014 Guatemala GSHS questionnaire; 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/gshs/2015_GSHS_Guatemala_Questionnaire_ES.pdf.

25. Kaess M, Parzer P, Haffner J, et al. Explaining gender differences in non-fatal suicidal behaviour among adolescents: a population-based study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:597. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-597

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.