Back to Journals » Clinical Interventions in Aging » Volume 12

Prescribing of psychotropic medication for nursing home residents with dementia: a general practitioner survey

Authors Cousins JM, Bereznicki LRE, Cooling NB, Peterson GM

Received 17 July 2017

Accepted for publication 9 September 2017

Published 3 October 2017 Volume 2017:12 Pages 1573—1578

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S146613

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Dr Richard Walker

Justin M Cousins, Luke RE Bereznicki, Nick B Cooling, Gregory M Peterson

School of Medicine, Faculty of Health, University of Tasmania, Hobart, TAS, Australia

Objective: The aim of this study was to identify factors influencing the prescribing of psychotropic medication by general practitioners (GPs) to nursing home residents with dementia.

Subjects and methods: GPs with experience in nursing homes were recruited through professional body newsletter advertising, while 1,000 randomly selected GPs from south-eastern Australia were invited to participate, along with a targeted group of GPs in Tasmania. An anonymous survey was used to collect GPs’ opinions.

Results: A lack of nursing staff and resources was cited as the major barrier to GPs recommending non-pharmacological techniques for behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD; cited by 55%; 78/141), and increasing staff levels at the nursing home ranked as the most important factor to reduce the usage of psychotropic agents (cited by 60%; 76/126).

Conclusion: According to GPs, strategies to reduce the reliance on psychotropic medication by nursing home residents should be directed toward improved staffing and resources at the facilities.

Keywords: dementia, nursing homes, general practitioners, antipsychotic agents, benzodiazepines

Impact statement

The findings of this research suggest that, according to general practitioners (GPs), reforming the prescribing of psychotropic medication in nursing home residents with behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia is best achieved by increasing the availability of non-pharmacological, diversional and other behavior modification resources.

Introduction

Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) occur in up to 90% of patients with dementia over the course of their illness, lead to distress to patients and caregivers, and increase health care costs associated with hospitalizations.1

Guidelines routinely suggest non-pharmacological interventions as the first-line therapy for BPSD, with certain psychotropic agents, such as antipsychotic medication, being second line due to the limited benefit and risk of serious adverse effects.2 The use of antipsychotics in these patients has been associated with an increased risk of mortality, hip fractures, thrombotic and cardiovascular events, and hospitalizations.3 Psychosocial approaches are preferred, tailoring them to the needs of the patient and creating a physical environment to reduce distress.4

There are concerns that there is a significant gap between guideline recommendations and practice in nursing home facilities when managing BPSD in Australia.5,6 Internationally, similar concerns have also been echoed recently.7 The factors involved in prescribing and withdrawing psychotropic agents by general practitioners (GPs) in the nursing home setting include GPs having a very low willingness to discontinue antipsychotics for fear of worsening symptoms8 and an overexpectation of benefit from antipsychotic therapy in BPSD.9 One study found that GPs were critical of their knowledge and management in this area and suggested that efforts should focus on educational interventions for GPs.10 In Australia, however, there are no published papers on the barriers to the evidence-based prescribing of psychotropic medication for people with BPSD in nursing homes.

We aimed to identify the factors influencing the prescribing of psychotropic medication to residents of Australian nursing homes with BPSD, and therefore determine strategies to promote more appropriate use of these medications.

Subjects and methods

Participant recruitment

Three iterative strategies were required to recruit enough Australian GPs to ensure an adequate sample size. Initially, GPs with experience in patient care in nursing homes were recruited through professional body advertising in newsletters in the state of Tasmania. This strategy had limited success. Next, 1,000 GPs mostly from southeastern Australia were randomly selected from an Australian Health Directory and mailed, with a follow up email sent to the surgeries with listed email addresses. Finally, a targeted group of 273 GPs in Tasmania who were known to have patients in nursing homes, based on their previous involvement in clinical activities, was invited by mail to complete the survey. While the GPs in this study were from only two states in Australia, their demographics were similar to the wider GP population in Australia.11 This study received ethical approval from the Tasmanian Social Sciences Human Research Ethics Committee (ethics reference number H0014615). Consent was assumed through completing the survey.

Questionnaire development

The anonymous 26-question survey was self-completed through either a paper-based version or an online version using Lime Survey.12 Participants were invited to enter a prize draw for an electronic device as an incentive.

This original questionnaire was developed from the clinical experience of the researchers and the results of international research.8–10,13,14 The questionnaire was piloted in a small group of GPs and pharmacists and refined based on their feedback.

Analysis

The outcomes of interest included GP perception of the factors that are most important to reduce psychotropic prescribing and barriers to using non-pharmacological techniques for BPSD, based on those found in the literature. The self-reported prescribing habits in BPSD and expectation of benefit were also of interest, with a Likert scale used to determine how effective the GPs believed the medication to be in practice. The survey relied on the GPs’ definition of settled and stabilized patients.

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 22 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).15 Chi-square tests were used, with a P-value of <0.05 considered significant. Responses to a 5-point Likert-type scale were collapsed into two categories. The first category included “rarely to some patients,” while the second category included “50% to most or all patients,” as given in Table 1. Reponses to ranking questions were presented with the top two ranked questions, as shown in Figures 1 and 2.

| Table 1 Prescribing habits |

| Figure 1 Barriers to non-pharmacological management of BPSD. |

| Figure 2 What would help reduce the usage of psychotropic agents in BPSD? |

Results

Demographics

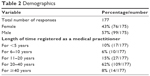

In total, 177 responses were returned. The majority (89%; 158/177) of the respondents were from Victoria and Tasmania, with most (61%; 109/177) having been registered as a medical practitioner for 20–40 years (Table 2). The uptake of the survey was probably limited by needing access to GPs with the appropriate patients. Response rates were difficult to calculate, with an unknown number of GPs ineligible to complete the survey because they did not have nursing home patients under their care at the time of the study. Of the 1,000 randomly selected GPs, it is expected that approximately half would have been eligible to complete the survey, based on a 2015/16 survey indicating 49% of GPs have provided care in a residential aged care facility in the previous month.16 This suggests that a response rate of ~21% was achieved (105/490). For the 273 Tasmanian GPs known to have residents in nursing homes, the response rate was 23% (64/273).

| Table 2 Demographics |

Barriers to non-pharmacological interventions and psychotropic medication reduction

“Aged care facility staffing and resources” was clearly highlighted as the number 1 barrier to non-pharmacological methods being utilized in BPSD. Likewise, directing funding to adequately staff facilities was the preference to reduce psychotropic usage in aged care (Figures 1 and 2).

Prescribing habits

Responses to selected questions concerning prescribing habits are given in Table 1. The vast majority expressed a desire to reduce psychotropic medication in completely settled or stabilized patients. When asked what they would do if a patient had been taking an antipsychotic for 6 months with no ongoing difficulties, 76% (135/177) indicated they would reduce the dosage of an antipsychotic with a view to cessation if possible. Similarly, when asked about benzodiazepine prescribing for BPSD in settled patients, 90% (159/176) indicated they would be likely to reduce or cease the benzodiazepine.

Management of BPSD

When asked if they routinely recommend non-pharmacological interventions before considering medication in BPSD, 81% (144/177) agreed or strongly agreed. About half (47%; 84/177) agreed that they feel they require more training to improve how they manage BPSD, with 24% (42/177) disagreeing.

The majority of respondents, 71% (126/177), indicated that they review their aged care residents’ medication three-monthly or more often, with 19% (34/177) reviewing the medication six-monthly, and the remainder annually or less.

Influences on prescribing for BPSD in nursing homes

Most GPs indicated that nurses (91%; 160/177) and family of residents (59%; 105/177) influence their prescribing. Interestingly, only one-third (33%; 58/177) indicated that nurses have requested psychotropic dose reductions and about the same from family (36%; 64/177). The majority of GPs (81%; 143/177) reported having had to decline a request from family or staff to prescribe an antipsychotic, with 39% (69/177) having to regularly refuse. Experienced GPs (20–40 years of experience) were significantly less likely (5%; 9/109) to rate pressure to prescribe from aged care facility staff as a barrier to non-pharmacological techniques than GP practising <5 years (29%; 5/17). Pharmacists were cited as the most likely health profession to request dose reductions (51%; 91/177); however, they were stated to only influence the actual prescribing by 28% (50/177). Over half of GPs (56%; 100/177) were confident that pharmacist-conducted residential medication management reviews (RMMRs) are beneficial in BPSD management, with a further 25% (44/177) who were unsure.

Concern for a reduced quality of life when withdrawing psychotropic agents received a mixed response, with 42% (75/177) agreeing they were concerned that withdrawing medication would impact negatively on the quality of life, leading to a return of challenging behaviors and disturbing psychological symptoms. About the same number (41%; 73/177) disagreed with this statement.

Confidence to reduce dosing after a failed first attempt was quite variable, with 35% (62/177) stating they did not feel confident to trial a second dose reduction, 23% (41/177) were undecided, and 42% (74/177) feeling confident to trial a second reduction attempt.

Discussion

Our findings imply that reforming the prescribing of antipsychotic medication in nursing homes is best targeted toward staffing levels and increasing the availability of diversional and other behavior modification resources. Similarly, a study from the Netherlands found staffing issues as a factor related to psychotropic drug prescribing.17

In this study, increasing funding to GPs was not shown as priority to reduce psychotropic prescribing in nursing homes. This contrasts with other studies into servicing nursing homes in Australia18 and the USA13 which found that levels of reimbursement and time were important barriers to GPs providing a range of services in this setting. It is possible that in our study GPs perceived that increased funding to them would not improve access to behavioral and support therapies in dementia care as they are not fund holders for these services.

GPs in our study, and similarly in a Dutch study,9 overestimated the benefit in symptom relief of second-generation antipsychotics compared with symptom outcomes in field studies19 and therapeutic guidelines,2 with 63% of GPs expecting benefit in half of all patients. The number needed to treat for second-generation antipsychotics in dementia is expected to be 5–14.19 This overexpectation of benefit, as given in Table 1, could be contributing to overusage. Better dissemination of practice guidelines cautioning about the limited benefit of antipsychotic medication in BPSD may prompt practitioners to more rationally prescribe these medications.

The preference for more training was expressed by around half of the respondents in our study. An educational solution to this problem is also supported by research from Ireland which found that efforts should focus on supporting GPs by means of educational interventions and health services promoting collaboration.10

Our research found a strong willingness, in principle, to reduce psychotropic medication in BPSD with, for example, two-thirds of GPs being confident to try a second reduction attempt after a failed attempt. Concern about a negative impact on the quality of life after drug withdrawal was evenly split among respondents. This contrasts to a study from Belgium, which found GPs resistant to reduce antipsychotic medication, including after a failed attempt, and their concern for a negative effect on the quality of life are a large barrier to discontinuation of antipsychotics.8

Our results suggest that nursing staff have the largest influence on prescribing psychotropic medication in this setting, indicating the importance of nursing home staffing and resources for non-pharmacological interventions. This is consistent with suggestions that any reforms to improve the treatment of mental illness and BPSD in nursing homes will need to begin with considering the physical design, staffing, and skills of staff within nursing homes.20 A Senate inquiry into the care of Australians living with dementia and BPSD in 2014 heard that staffing levels and training are inadequate, with no legislated staffing ratios in nursing homes.21 Stakeholders reported that restraints are being used too readily to cover staff and resourcing limitations. In the inquiry, the Australian Medical Association (AMA) indicated that, with under-resourced aged care facilities and limited qualified nursing staff and sufficient numbers of carers, the need for restraint is an unfortunate reality.

Research internationally is mixed in relation to staff numbers and qualifications, and the quality of nursing homes in general. A systematic review found that focusing on the numbers of nurses fails to address the influence of other staffing factors, including training and care organization, with quality being a difficult concept to capture.22 It goes on to state that further research is needed to determine the most cost-effective manner to utilize the combination of nursing skill levels. Another study found that there was no association with caregiver professional training and the care given, with a complex relationship between staffing and the quality of care provided.23 While our study demonstrates the perceived need for increased staffing and resources at the facility, further research is required to determine the best models for the delivery of cost-effective and efficient non-pharmacological interventions in BPSD. This dementia care redesign in nursing homes could be informed by Effective Practice and Organization of Care (EPOC) methodology.24 Repeating a similar survey in nursing staff to assess their experiences would also be worthwhile to help determine whether these perceptions are shared across professions.

Limitations of this study include the relatively small sample size and the apparent low response rate. A further limitation is relying on the GPs’ recall of what they would prescribe or withdraw in certain situations. This limitation is likely to bias the responses toward the perceived best practice; however, it will provide an idea of what the GPs would like to do if there were no barriers to this practice. Although the questionnaire was not validated, it was sampled in a small number of GPs before use and refined based on their feedback. In addition, the types and severity of dementia did not form part of the survey.

Conclusion

GPs described inadequate nursing staff levels and resources as the main factors that limit the use of non-pharmacological interventions and their ability to reduce the usage of psychotropic agents in nursing homes.

Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge Dr Juanita Westbury for her early input.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Cerejeira J, Lagarto L, Mukaetova-Ladinska EB. Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Front Neurol. 2012;3:73. | ||

eTG. Therapeutic Guidelines. eTG Complete. Melbourne, VIC, Australia: Therapeutic Guidelines Limited; 2015. | ||

Chiu Y, Bero L, Hessol NA, Lexchin J, Harrington C. A literature review of clinical outcomes associated with antipsychotic medication use in North American nursing home residents. Health Policy. 2015;119(6):802–813. | ||

Association IP. The IPA Complete Guides to Behavioural and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia, BPSD, Specialists Guide. International Psychogeriatric Association; Northfield, IL, USA: 2015. | ||

NPS_MedicineWise [webpage on the Internet]. Antipsychotic Overuse in Dementia – Is There a Problem? 2013. Available from: http://www.nps.org.au/publications/health-professional/health-news-evidence/2013/antipsychotic-dementia. Accessed June 27, 2016. | ||

Hilmer SN, Gnjidic D. Rethinking psychotropics in nursing homes. Med J Aust. 2013;198(2):77. | ||

Helvik AS, Saltyte Benth J, Wu B, Engedal K, Selbaek G. Persistent use of psychotropic drugs in nursing home residents in Norway. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):52. | ||

Azermai M, Vander Stichele RR, Van Bortel LM, Elseviers MM. Barriers to antipsychotic discontinuation in nursing homes: an exploratory study. Aging Ment Health. 2014;18(3):346–353. | ||

Cornege-Blokland E, Kleijer BC, Hertogh CM, van Marum RJ. Reasons to prescribe antipsychotics for the behavioral symptoms of dementia: a survey in Dutch nursing homes among physicians, nurses, and family caregivers. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(1):80.e1–e6. | ||

Buhagiar K, Afzal N, Cosgrave M. Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia in primary care: a survey of general practitioners in Ireland. Ment Health Fam Med. 2011;8(4):227–234. | ||

The Department of Health [webpage on the Internet]. General Practice Statistics. 2017. Available from: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/General+Practice+Statistics-1. Accessed August 31, 2017. | ||

LimeSurvey [homepage on the Internet]. LimeSurvey Project Team/Carsten Schmitz (2015)/LimeSurvey: An Open Source Survey Tool/LimeSurvey Project. Hamburg, Germany: 2015. Available from: http://www.limesurvey.org. Accessed September 12, 2017. | ||

Hinton L, Franz CE, Reddy G, Flores Y, Kravitz RL, Barker JC. Practice constraints, behavioral problems, and dementia care: primary care physicians’ perspectives. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(11):1487–1492. | ||

Cohen-Mansfield J, Jensen B. Physicians’ perceptions of their role in treating dementia-related behavior problems in the nursing home: actual practice and the ideal. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2008;9(8):552–557. | ||

IBM_Corp. IBM Corp. Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2013. | ||

Britt H, Miller GC, Henderson J, et al. [webpage on the Internet]. General Practice Activity in Australia 2015–2016. General Practice Series No. 40. 2016. Available from: http://purl.library.usyd.edu.au/sup/9781743325131. Accessed September 12, 2017. | ||

Smeets CH, Smalbrugge M, Zuidema SU, et al. Factors related to psychotropic drug prescription for neuropsychiatric symptoms in nursing home residents with dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(11):835–840. | ||

Gadzhanova S, Reed R. Medical services provided by general practitioners in residential aged-care facilities in Australia. Med J Aust. 2007;187(2):92–94. | ||

Schneider LS, Dagerman K, Insel PS. Efficacy and adverse effects of atypical antipsychotics for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(3):191–210. | ||

Looi JC, Macfarlane S. Psychotropic drug use in aged care facilities: a reflection of a systemic problem? Med J Aust. 2014;200(1):13–14. | ||

Commonwealth of Australia. Care and management of younger and older Australians living with dementia and behavioural and psychiatric symptoms of dementia (BPSD). In: Australia Co, editor. Community Affairs References Committee. Canberra, ACT, Australia: 2014. | ||

Spilsbury K, Hewitt C, Stirk L, Bowman C. The relationship between nurse staffing and quality of care in nursing homes: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48(6):732–750. | ||

Winslow JH, Borg V. Resources and quality of care in services for the elderly. Scand J Public Health. 2008;36(3):272–278. | ||

Hodgkinson B, Haesler EJ, Nay R, O’Donnell MH, McAuliffe LP. Effectiveness of staffing models in residential, subacute, extended aged care settings on patient and staff outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(6):Cd006563. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.