Back to Journals » Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management » Volume 12

Preoperative risk factors in total thyroidectomy of substernal goiter

Authors Bove A, Di Renzo RM, D'Urbano G, Bellobono M, D'Addetta V, Lapergola A, Bongarzoni G

Received 13 April 2016

Accepted for publication 11 July 2016

Published 28 November 2016 Volume 2016:12 Pages 1805—1809

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S110464

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Garry Walsh

Aldo Bove, Raffaella Maria Di Renzo, Gauro D’Urbano, Manuela Bellobono, Vincenzo D’ Addetta, Alfonso Lapergola, Giuseppe Bongarzoni

Department of Medicine, Dentistry and Biotechnology, University “G. d’Annunzio” Chieti-Pescara, Chieti Scalo, Italy

Abstract: The definition of substernal goiter (SG) is based on variable criteria leading to a considerable variation in the reported incidence (from 0.2% to 45%). The peri- and postoperative complications are higher in total thyroidectomy (TT) for SG than that for cervical goiter. The aim of this study was to evaluate the preoperative risk factors associated with postoperative complications. From 2002 to 2014, 142 (8.5%; 98 women and 44 men) of the 1690 patients who underwent TT had a SG. We retrospectively evaluated the following parameters: sex, age, histology, pre- and retrovascular position, recurrence, and extension beyond the carina. These parameters were then related to the postoperative complications: seroma/hematoma, transient and permanent hypocalcemia, transient and permanent laryngeal nerve palsy, and the length of surgery. The results were further compared with a control group of 120 patients operated on in the same period with TT for cervical goiter. All but two procedures were terminated via cervicotomy, where partial sternotomies were required. No perioperative mortality was observed. Results of the statistical analysis (Student’s t-test and Fisher’s exact test) indicated an association between recurrence and extension beyond the carina with all postoperative complications. The group that underwent TT of SG showed a statistically significant higher risk for transient hypocalcemia (relative risk =1.767 with 95% confidence interval: 1.131–2.7605, P=0.0124, and need to treat =7.1) and a trend toward significance for transient recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy (relative risk =6.7806 with 95% confidence interval: 0.8577–53.2898, P=0.0696, and need to treat =20.8) compared to the group that underwent TT of cervical goiter. TT is the procedure to perform in SG even if the incidence of complications is higher than for cervical goiters. The major risk factors associated with postoperative complications are recurrence and extension beyond the carina. In the presence of these factors, greater care should be taken.

Keywords: substernal goiter, total thyroidectomy, complications

Introduction

Total thyroidectomy (TT) is the most suggested treatment for substernal goiter (SG). Several studies attribute the SG with a degree of variability between 2% and 48%.1 This high degree of variability is mainly due to the fact that there is a lack of a unanimous definition of SG, making it difficult to compare results.2

The symptoms reported by patients are caused by the compression of the SG on the trachea, on the esophagus, and on the vascular structures. Even in few cases where the SG is asymptomatic, surgery is the most suggested treatment because of the continuous growth of the goiter and also there is a high risk that it turns malignant.3

SG is classified as primary and secondary depending on the origin of the blood supply: the primary, rare (1%), originates in the mediastinum vessels, whereas the secondary originates in the cervical vessel.

The extension into the mediastinum is aided by the anatomical continuity between the neck and the thorax, by the traction caused from the negative intra-thoracic pressure and by constitutional factors such as short neck and strong muscles.

In the majority of cases, surgery with TT is feasible through a cervical access, while sternotomy (ST) is required only in those cases of suspected infiltration of mediastinal structures, extension beyond the carina, or recurrence following a partial thyroidectomy.

The incidence of intraoperative and postoperative complications is generally higher in ST than in TT for cervical goiter (CG).4 Reoperation, the size of the extension of the goiter in the thorax, and/or the retrovascular position are all factors that explain the difference of TT in SG and could affect the outcome of the surgery. The aim of this study is to identify which of those above-mentioned preoperative risk factors are associated with a higher incidence of post TT complications for SG.

Methods

Dentistry and Biotechnology, University “G. d’Annunzio” Chieti-Pescara ethics committee does not require ethical approval be sought for retrospecive studies, nor does it require patient consent to participate in the study. From January 2002 to December 2014, we performed 1690 TT and SG (8.5%) was diagnosed in 142 cases (98 females and 44 males with a mean age 58 years [35–78]). We define SG as a goiter which extends at least 3 cm from the sternal manubrium when the patient is in operative position and with hyper-extended neck. Anatomically, we divided SG into prearterial (103 patients) and retroarterial (39 patients). All patients underwent TT. We retrospectively evaluated the following parameters: sex, age, histology, anatomical classification, recurrence, and extension beyond the carina. These parameters were then related to the postoperative complications: seroma/hematoma, transient and permanent hypocalcemia, transient and permanent laryngeal nerve palsy (recurrent laryngeal nerve), and the length of surgery. Indices of thyroid functionality and calcemia were controlled before surgery. One hundred and twenty patients showed compressive symptoms including dry cough (110 patients), dyspnea under strain (15 patients), dysphagia (35 patients), and dysphonia (1 patient).

Hypocalcaemia is defined to have a value of calcium level <8 mg/dL and is defined permanent when having this value for >1 year.

We did not use post-prophylactic therapy for hypocalcemia after TT. We performed daily controls of calcium level values and adapted therapy to the patient’s clinical condition. In the last 3 years we utilized the parathyroid hormone dosage at 1 hour in order to evaluate early the patients to treat.

All the patients were examined pre and postoperatively with a laryngoscope. For patients with paralysis of the vocal cords for >1 year from the operation, this condition is considered permanent. The scheduled follow-ups of the main parameters were set at 1, 6, and 12 months postoperatively.

The results were further compared with a control group of 120 patients operated in the same period with TT for CG.

Statistical analysis

All qualitative parameters were summarized as frequency and percentage and quantitative parameters as mean and standard deviation. Between-group differences for intraoperative parametric and nonparametric parameters were evaluated with the two-tailed Student’s t-test and the Fisher’s exact test. The effect of the selected surgical procedure was evaluated with relative risk (RR), 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), and need to treat (NTT). An alpha level of 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Results

Operative mortality did not occur. All the surgical procedures were conducted through a cervical access except in two cases in which a partial ST was necessary: one due to adherence in a recurrence and the other for extension beyond the carina.

All the operated patients usually had preoperatively normal calcemia while for preoperative laryngoscopy one patient reported a paralysis in the inferior laryngeal nerve due to a former surgery.

The average postoperative hospital stay was of 3.8 days (3–8 days) and one patient required a blood transfusion. The median stay in the control group was of 2.5 days (2–4 days).

With regard to complications, we had three patients (2.1%) with postoperative seroma and/or hematoma. Only one patient required a surgical revision. Temporary hypocalcemia occurred in 46 patients (33%), reaching higher values in patients with goiter extended beyond three carinas (66.6%) and in those in whom it recurred after primary surgery (52.1%). Permanent hypocalcemia occurred in four patients (2.8%), also belonging to the two subgroups aforementioned (Table 1).

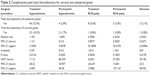

| Table 1 Results |

Temporary dysphonia occurred in eight patients (5.6%) where six of them were in the group with extension beyond the carina. Permanent paralysis affected three patients (2.1%). Finally, the duration of surgery had a median of 118 minutes – longer for relapse cases (165 minutes) and for carina extension (160 minutes). Compressive symptoms progressively disappeared within 12 months with the exception of five patients (4%) still affected by dysphagia.

Statistical analysis (Student’s t-test and Fisher’s exact test) showed a significant correlation between relapse cases and those with extension beyond the carina and the incidence of postoperative transient and permanent hypocalcemia and transient and permanent laryngeal nerve palsy (Table 1).

Statistically significant differences in intraoperative parameters were not observed with the control group. The group that underwent TT of SG showed a statistically significant higher risk for transient hypocalcemia (RR =1.767 with 95% CI: 1.131–2.7605, P=0.0124, and NTT =7.1) and a trend toward significance for transient recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy (RR =6.7806 with 95% CI: 0.8577–53.2898, P=0.0696, and NTT =20.8) compared to the group that underwent TT of CG (Table 2).

| Table 2 Complications post total thyroidectomy for cervical and substernal goiter |

Discussion

The mechanisms that lead to the development of SG are diverse and contribute to the growth of the goiter in the mediastinum. Unfortunately, there is no consensus on the definition of SG, so the incidence varies across different case studies, and, above all, makes it difficult to compare results.5 The indication for surgery is not strongly supported by scientific evidence,6 even though many authors believe SG to be a surgical indication due to the ineffectiveness of medical treatment and the risks of obstruction of breathing patterns/airways and the risk it will turn into malignancy.7

Various studies have suggested that postoperative morbidity for SG may be higher compared to CG surgery.8

Many authors9 emphasized the necessity of planning in advance the ST in the treatment of SG. On the other hand, we believe that only in few cases, <2% in our studies, ST is required. A good surgical preparation, following a surgical plan of dissection, will permit a safe thyroidectomy. A preoperative study with a cervical–thorax computed tomography scan allows also the extension and intra-thoracic assessment of the goiter.10

The case of ectopic goiter is peculiar, so an extra-cervical access is necessary.

Postoperative mobility for SG is reported to be higher than to CG surgery.11 Our study confirms this data. In particular, temporary postoperative hypocalcemia had a greater occurrence when compared to total thyroidectomies for CG. Various factors can influence the incidence of postoperative hypocalcemia for total thyroidectomies.12 Also, temporary palsy of the recurrent laryngeal nerve has shown a trend toward significantly greater occurrence in SG surgery.

Postoperative hospital stay was longer for patients with SG but not with statistically significant data. In the majority of cases, temporary postoperative hypocalcemia is the reason for the delay in discharge.13 The use of early markers for hypocalcemia allowed an earlier treatment and a more rapid discharge for these patients.14

In our study, we evaluated the preoperative risk factors that could be associated with a higher incidence of postoperative complications in patients with SG.

Statistical analysis has shown that the major risk factors are recurrence and extension of the goiter beyond the carina. We considered the growth of the goiter beyond the carina a more significant risk factor compared to the volume of the goiter itself.

In the case of relapse, in fact, adhesions and neo-blood supply are often present and can interfere with the correct surgical dissection. Furthermore, the intra-thoracic extension of SG is a significant factor in postoperative risk.15 Only one patient necessitated a blood transfusion due to a very expanded goiter.

Sancho et al reported an incidence of 37% in temporary hypoparathyroidism and 14% of temporary vocal paralysis for SG cases where the tracheal carina is reached.16

Concerning the goiter’s position (pre- or retroarterial), we are aware that the retroarterial ones lead to a higher risk of complications. However, this data has not been confirmed by the statistical analysis, maybe because of the small number of cases reported. On the other hand, it is remarkable that five patients presented with dysphagia 1 year after the surgery. This is probably caused by swallowing motor disorders.

In a study by Raffaelli et al, the duration of surgery and postoperative hospital stay was longer for patients operated for SG. They conclude that the experience of the surgical team is essential to obtain good results.17

Certainly, a dedicated surgical team can handle complex cases with the minimum postoperative complications.

In our study, however, we tried to demonstrate that these two risk factors, recurrence and extension beyond the carina, make surgery more challenging. In the presence of these factors, greater care should be taken and the patients should be directed to a dedicated team.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Ríos A, Rodríguez JM, Balsalobre MD, Tebar FJ, Parrilla P. The value of various definitions of intrathoracic goiter for predicting intra-operative and postoperative complications. Surgery. 2010;147(2):233–238. | ||

Huins CT, Georgalas C, Mehrzad H, Tolley NS. A new classification system for retrosternal goitre based on a systematic review of its complications and management. Int J Surg. 2008;6(1):71–76. | ||

Hedayati N, McHenry CR. The clinical presentation and operative management of nodular and diffuse substernal thyroid disease. Am Surg. 2002;68(3):245–251. | ||

Testini M, Gurrado A, Avenia N, et al. Does mediastinal extension of the goiter increase morbidity of total thyroidectomy? A multicenter study of 19,662 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(8):2251–2259. | ||

Zambudio AR, Rodríguez J, Riquelme J, Soria T, Canteras M, Parrilla P. Prospective study of postoperative complications after total thyroidectomy for multinodular goiters by surgeons with experience in endocrine surgery. Ann Surg. 2004;240(1):18–25. | ||

White ML, Doherty GM, Gauger PG. Evidence-based surgical management of substernal goiter. World J Surg. 2008;32(7):1285–1300. | ||

Chen AY, Bernet VJ, Carty SE, et al. Surgical Affairs Committee of the American Thyroid Association. American Thyroid Association statement on optimal surgical management of goiter. Thyroid. 2014;24(2):181–189. | ||

Pieracci FM, Fahey TJ 3rd. Substernal thyroidectomy is associated with increased morbidity and mortality as compared with conventional cervical thyroidectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205(1):1–7. | ||

Qureishi A, Garas G, Tolley N, Palazzo F, Athanasiou T, Zacharakis E. Can pre-operative computed tomography predict the need for a thoracic approach for removal of retrosternal goitre? Int J Surg. 2013;11(3):203–208. | ||

Mercante G, Gabrielli E, Pedroni C, et al. CT cross-sectional imaging classification system for substernal goiter based on risk factors for an extracervical surgical approach. Head Neck. 2011;33(6):792–799. | ||

Testini M, Gurrado A, Bellantone R, et al. Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy and substernal goiter. An Italian multicenter study. J Visc Surg. 2014;151(3):183–189. | ||

Bove A, Bongarzoni G, Dragani G, et al. Should female patients undergoing parathyroid-sparing total thyroidectomy receive routine prophylaxis for transient hypocalcemia? Am Surg. 2004;70(6):533–536. | ||

Landerholm K, Wasner AM, Järhult J. Incidence and risk factors for injuries to the recurrent laryngeal nerve during neck surgery in the moderate-volume setting. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2014;399(4):509–515. | ||

Bove A, Di Renzo RM, Palone G, et al. Early biomarkers of hypocalcemia following total thyroidectomy. Int J Surg. 2014;12(Suppl 1):S202–S204. | ||

Khairy GA, Al-Saif AA, Alnassar SA, Hajjar WM. Surgical management of retrosternal goiter: Local experience at a university hospital. Ann Thorac Med. 2012;7(2):57–60. | ||

Sancho JJ, Kraimps JL, Sanchez-Blanco JM, et al. Increased mortality and morbidity associated with thyroidectomy for intrathoracic goiters reaching the carina tracheae. Arch Surg. 2006;141(1):82–85. | ||

Raffaelli M, De Crea C, Ronti S, Bellantone R, Lombardi CP. Substernal goiters: incidence, surgical approach, and complications in a tertiary care referral center. Head Neck. 2011;33(10):1420–1425. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.