Back to Journals » Infection and Drug Resistance » Volume 11

Poor adherence is a contributor to viral breakthrough in patients with chronic hepatitis B

Authors Wang L, Chen P, Zheng C

Received 6 September 2018

Accepted for publication 28 September 2018

Published 8 November 2018 Volume 2018:11 Pages 2179—2185

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S186719

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Suresh Antony

Liguo Wang,1,* Peng Chen,2,* Chao Zheng3

1Department of Infectious Diseases, First Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University, Fujian Province, China; 2Department of Emergency, Xinglin Hospital, First Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University, Fujian Province, China; 3Department of Respiratory, First Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University, Fujian Province, China

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Objective: The objective of this study was to explore the risk factors of poor adherence of nucleoside analogs (NUC) treatment in chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients and the virological changes in patients with poor adherence.

Subjects and methods: A total of 205 CHB patients were enrolled. The patients’ demographic data and family history were collected. NUC adherence was calculated every 12 weeks as follows: number of NUC tablets taken by the patients was divided by the number of NUC tablets prescribed. NUC adherence > 90% was defined as good adherence of NUC treatment.

Results: NUC adherence of male patients was significantly lower than that of female patients. Adherence among patients with previous NUC treatment was poorer than that of patients without previous NUC treatment. Multivariate analysis indicated that female gender (OR =0.367, P=0.013) was the protective factor for NUC adherence in CHB patients, while pretreatment with NUC was the risk factor for NUC adherence (OR =3.209, P=0.002). A total of six patients in the good adherence group experienced virological breakthroughs while 15 of 77 patients in the poor adherence group experienced virological breakthroughs (P=0.001). Similar trends were observed in NUC resistance. Four of the 128 patients with good adherence developed NUC resistance while nine of the 77 patients with poor adherence developed resistance (P=0.015). Multivariate analysis suggested that pretreatment with NUC (OR =3.133, P=0.031), NUC drugs (OR = 3.951, P=0.010), and adherence (OR =2.749, P=0.046) were independent risk factors associated with virological breakthroughs and that NUC drugs (OR =7.083, P=0.005) and poor adherence (OR =4.951, P=0.009) were independent risk factors for NUC resistance.

Conclusion: Male gender and pretreatment with NUC were risk factors associated with NUC adherence. Poor NUC adherence is more likely to induce virological breakthroughs and NUC resistance. For patients with poor NUC adherence, it is necessary to give timely education to improve treatment adherence.

Keywords: chronic hepatitis B, adherence, nucleoside analogs, virological breakthroughs, risk factors

Introduction

Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) is still one of the major health burdens, especially in Asian-Pacific countries.1 There are about 350 million patients infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV) worldwide, including about 20 million CHB patients.2,3 At present, the oral nucleoside analogs (NUC) approved for the treatment of CHB include lamivudine (LAM), adefovir (ADV), telbivudine (LDT), entecavir (ETV), and tenofovir (TDF).4–6 Although the current guideline suggested that hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) seroconversion is the ideal endpoint for CHB treatment,1 NUC has only a mild effect on HBsAg elimination, which means that NUC antiviral treatment for CHB patients takes a long time, even for a lifetime.3,7,8

Premature withdrawal of NUC antiviral treatment may cause virological breakthrough, HBV reactivation, and even liver failure.9–11 Studies by Chotiyaputta et al found that the proportion of patients with good adherence of NUC treatment was about 55%.12,13 In China, due to the economic burden and medical insurance policy, the adherence of CHB is even lower.7,11 Premature withdrawal of NUC treatment and the poorly adherence behavior may cause virological fluctuations.10,12,14 Screening for populations with poor adherence and timely interventions such as adherence education may improve patients’ adherence and avoid adverse prognosis. However, the risk factors for poor adherence in CHB patients have not been reported before. Therefore, in this study, we dynamically observed the NUC adherence in CHB patients and explore the risk factors for poor adherence of NUC treatment. Also, we explored the virological changes in patients with poor adherence.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

From November 2014 to July 2017, patients with chronic HBV infection receiving NUC treatment were enrolled. The diagnostic criterion for CHB is serum HBsAg persistently positive for at least 6 months. Exclusion criteria included cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, autoimmune liver disease, decompensated liver disease, and HIV, hepatitis C and hepatitis D infections. Breakthrough is defined as an increase of serum HBV DNA >1 log IU/mL from nadir of initial response during therapy, as confirmed 4 weeks later. Patients who had not been treated previously means that those patients were treatment naïve at the time of enrollment, and those patients started antiviral treatment from the time of enrollment. Previously treated patients mean those patients who have already received antiviral treatment, including changes to another type of NUC and maintaining NUC treatment.

Adherence calculation

The patients’ demographic data and family history were collected. NUC adherence was calculated every 12 weeks. NUC adherence = number of NUC tablets taken / number of NUC tablets prescribed. NUC adherence >90% was defined as good performance of NUC adherence.

Data analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean and SD, and categorical variables were expressed as percentages. The chi-squared test or t-test was applied to determine whether the results were statistically different. Univariate and multivariate analyses were used to explore the factors associated with viral breakthrough and drug resistance. The statistical significance of all tests was set as P<0.05 by two-tailed tests. Data analyses and quality control procedures were performed using SPSS for Windows, version 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board of First Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University had approved this study. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All participants enrolled in this study provided written informed consent.

Results

Demographic data difference by NUC adherence

A total of 205 patients were enrolled. Among them, 128 patients were in the good performance group with adherence >90%, while the other 77 patients were in the poor performance group. We found that NUC adherence of male patients was significantly worse than that of female patients. In addition, adherence among patients with previous NUC treatment was poorer than that of patients without previous NUC treatment (Table 1).

To further determine if gender and NUC treatment history influence NUC adherence, we dynamically compared the adherence changes in each subgroup. The results are shown in Figure 1. We found that female patients were more compliant than male patients at 12, 24, 36, and 48 weeks treatment. Similarly, patients with previous NUC treatment had poorer adherence than patients without previous treatment at 12, 24, 36, and 48 weeks treatment.

Univariate and multivariate analyses for NUC adherence

Univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted to explore the independent factors associated with poor NUC adherence. Univariate analysis showed that male gender and previous NUC treatment were risk factors for poor NUC adherence in CHB patients. This result was verified in the multivariate analysis. Multivariate analysis indicated that female gender (OR =0.367, P=0.013) was the protective factor for NUC adherence in CHB patients, whereas pretreatment with NUC was the risk factor for NUC adherence (OR =3.209, P=0.002), as shown in Table 2.

| Table 2 Univariate and multivariate analyses of variables for poor adherence Abbreviations: HBeAg, hepatitis B virus e antigen; NUC, nucleos(t)ide analog. |

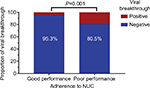

Association between adherence with virological breakthroughs and resistance

Although the relationship between poor adherence and virological fluctuations has been reported, the association between poor adherence with virological breakthroughs and NUC resistance remains unclear. We explored the relationship between adherence and virological breakthroughs. We found that six patients in the good adherence group experienced virological breakthroughs after 48 weeks of NUC treatment, while 15 of 77 patients in the poor adherence group experienced virological breakthroughs. The difference was statistically significant (P=0.001, Figure 2).

Virological breakthroughs are closely related to NUC resistance. We further analyzed the difference in the proportion of NUC resistance. The results are shown in Figure 3. We found that four of 128 patients with good adherence developed NUC resistance after 48 weeks of NUC treatment, while nine of 77 patients with poor adherence developed resistance. The difference was statistically significant (P=0.015).

Among the four drug-resistant patients in the good adherence group, the resistance mutations were two cases of rtM204V (one case in LAM group and one in LDT group), one case of rtM204V+rtL180M (LAM group), and one case of rtA181T/V (LDT group). Among the nine drug-resistant patients in the poor adherence group, there were four cases of rtM204V (two in LAM group and two in LDT group), three cases of rtA181T/V (two in LAM group and one in LDT group), and two cases of rtM204V+rtL180M (LDT group). However, we did not find a relationship between mutation types and patients’ adherence.

Risk factors associated with virological breakthroughs and NUC resistance

A multivariate analysis for virological breakthroughs was conducted to further validate the relationship between NUC adherence and virological breakthroughs. The results showed that age, previous treatment of NUC, different NUC treatment, and NUC adherence were risk factors associated with virological breakthroughs. Multivariate analysis suggested that only pretreatment with NUC (OR =3.133, P=0.031), NUC drugs (OR =3.951, P=0.010), and NUC adherence (OR =2.749, P=0.046) were independent risk factors associated with virological breakthroughs in CHB patients. The results are shown in Table 3.

| Table 3 Univariate and multivariate analyses of variables for viral breakthrough Abbreviations: HBeAg, hepatitis B virus e antigen; NUC, nucleos(t)ide analog. |

We also performed a multivariate analysis of NUC resistance in CHB patients. As shown in Table 4, pretreatment with NUC, NUC drugs, and NUC adherence were factors associated with NUC resistance. However, multivariate analysis suggested that only NUC drugs (OR =7.083, P=0.005) and poor adherence to NUC (OR =4.951, P=0.009) were independent risk factors for NUC resistance.

| Table 4 Univariate and multivariate analyses of variables for NUC resistance Abbreviations: HBeAg, hepatitis B virus e antigen; NUC, nucleos(t)ide analog. |

Discussion

The goal of CHB treatment is to improve the quality of life and survival rate and to reduce the incidence of cirrhosis, decompensated cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and related mortality.4,14–16 The goal can be achieved by inhibiting HBV replication to reduce liver histological inflammation.9,17,18 However, chronic HBV infection cannot be completely eradicated due to the presence of covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA). NUC drugs can inhibit HBV replication, but cannot eliminate cccDNA.7,19 Therefore, the treatment period of NUC drugs is very long, and patients may need to take the drugs for a lifetime. However, many CHB patients withdraw from NUC treatment prematurely. Premature discontinuation of NUC treatment can cause a series of poor prognosis.20,21 Therefore, early screening of CHB patients with poor adherence improves their adherence and reduces the possibility of long-term poor prognosis. According to the results of this study, male gender and pretreatment with NUC were risk factors associated with NUC adherence. Moreover, poor NUC adherence was more likely to induce virological breakthroughs and NUC resistance.

According to the results of this study, male gender and NUC pretreatment history have an impact on drug adherence. Female patients have better performance than male patients in drug adherence, and patients with previous NUC treatment had poorer performance than patients without previous treatment. This suggests that in clinical practice, more attention should be paid to male patients and NUC-treated CHB patients. For those population, if there is a virological breakthrough, NUC adherence issue should be taken into consideration. It is necessary to give timely guidance about adherence to improve patients’ compliance. Studies have reported that adherence is related to the type of NUC.10,13 Among the patients treated with LAM, the adherence was poor. This result was confirmed in our study. However, the reason is not clear until now. Since LAM is not a first-line NUC, it is not recommended for CHB patients for antiviral treatment in recent years. However, there are still some CHB patients who continue to use LAM for antiviral treatment. This may be because these patients do not often go back to the hospital for follow-up, or due to the financial burden, they cannot afford to switch to first-line NUC. It is still not known why this type of NUC is related to adherence. This is a question worthy of further investigation.

Available CHB guidelines suggest that patients can be considered for drug withdrawal after HBsAg seroconversion.1,6 However, studies reported that the decrease of HBsAg level during NUC antiviral therapy is very slow and that some CHB patients need to take NUC for life.22–24 It was reported that about 50%–75% patients with hypertension had good adherence and that the proportion of hyperlipidemia patients with good adherence was about 70%–94%.25–29 However, the proportion of CHB patients with good adherence was low.10,11 Lack of knowledge of CHB may be one of the reasons for poor adherence in CHB patients compared to patients with hypertension and hyperlipidemia. Improving patients’ knowledge of CHB may improve NUC adherence in CHB patients. In this study, patients enrolled had relatively high adherence because all patients were informed to report their NUC adherence information. In clinical practice, CHB patients may have even lower NUC adherence. In China, many patients do not know much about the disease of CHB, which leads them to discontinue NUC treatment prematurely.7 Therefore, necessary health services as adherence interventions, including adherence education, public health lecture, and close monitoring of adherence, etc. Especially for high-risk population with poor adherence, timely adherence education is necessary.

This study found that previous NUC treatment, different NUC drugs, and poor NUC adherence are independent risk factors for virological breakthrough, and different NUC drugs and poor NUC adherence are risk factors for virological resistance. Previous studies showed that pretreatment with NUC may result in a reduction in the resistance barrier for subsequent treatment.3,9 Patients treated with LAM will reduce the resistance barrier of ETV.9 It is well established that the resistance barriers of LAM and LDT are significantly lower than those of ETV and TDF.6 We confirmed in previous reports that CHB patients treated with LAM and LDT are more likely to develop NUC resistance than ETV and TDF treatment. We also found that poor NUC adherence can also lead to virological breakthrough and virological resistance. It is important to pay attention to the adherence of patients with CHB to reduce virological breakthrough and NUC resistance. Some factors such as income, instruction level, and urban/rural dwelling may affect the NUC adherence. However, these factors were not included in the study because of the sample size of the study is relatively small. Majority of patients are low-income and low-educated patients in China. A clinical trial with large sample is needed to analyze the relationship between social parameters and adherence.

There are some limitations in this study. This study was a single-center study. The follow-up period was only 48 weeks. In addition, the sample size of this study is relatively small, so the results may be biased. The importance of adherence education and the effects of adherence on the long-term prognosis of CHB patients (such as cirrhosis, HCC incidence) also need to be confirmed by prospective large-scale multicenter clinical studies.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Sarin SK, Kumar M, Lau GK, et al. Asian-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B: a 2015 update. Hepatol Int. 2016;10(1):1–98. | ||

Cai SH, Lv FF, Zhang YH, Jiang YG, Peng J. Dynamic comparison between Daan real-time PCR and Cobas TaqMan for quantification of HBV DNA levels in patients with CHB. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:85. | ||

Cai S, Cao J, Yu T, Xia M, Peng J. Effectiveness of entecavir or telbivudine therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection pre-treated with interferon compared with de novo therapy with entecavir and telbivudine. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(22):e7021. | ||

Ou H, Cai S, Liu Y, Xia M, Peng J. A noninvasive diagnostic model to assess nonalcoholic hepatic steatosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2017;10(2):207–217. | ||

Peng J, Cai S, Yu T, Chen Y, Zhu Y, Sun J. Aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index - a reliable predictor of therapeutic efficacy and improvement of Ishak score in chronic hepatitis B patients treated with nucleoside analogues. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2016;76(2):133–142. | ||

Terrault NA, Bzowej NH, Chang KM, et al; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.. AASLD guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2016;63(1):261–283. | ||

Peng J, Cao J, Yu T, et al. Predictors of sustained virologic response after discontinuation of nucleos(t)ide analog treatment for chronic hepatitis B. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(4):245–253. | ||

Cai SH, Lu SX, Liu LL, Zhang CZ, Yun JP. Increased expression of hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha transcribed by promoter 2 indicates a poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2017;10(10):761–771. | ||

Cai S, Yu T, Jiang Y, Zhang Y, Lv F, Peng J. Comparison of entecavir monotherapy and de novo lamivudine and adefovir combination therapy in HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B with high viral load: 48-week result. Clin Exp Med. 2016;16(3):429–436. | ||

Peng J, Yin J, Cai S, Yu T, Zhong C. Factors associated with adherence to nucleos(t)ide analogs in chronic hepatitis B patients: results from a 1-year follow-up study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:41–45. | ||

Xue X, Cai S, Ou H, Zheng C, Wu X. Health-related quality of life in patients with chronic hepatitis B during antiviral treatment and off-treatment. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:85–93. | ||

Chotiyaputta W, Hongthanakorn C, Oberhelman K, Fontana RJ, Licari T, Lok AS. Adherence to nucleos(t)ide analogues for chronic hepatitis B in clinical practice and correlation with virological breakthroughs. J Viral Hepat. 2012;19(3):205–212. | ||

Chotiyaputta W, Peterson C, Ditah FA, Goodwin D, Lok AS. Persistence and adherence to nucleos(t)ide analogue treatment for chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2011;54(1):12–18. | ||

Wu X, Cai S, Li Z, et al. Potential effects of telbivudine and entecavir on renal function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Virol J. 2016;13:64. | ||

Cai S, Li Z, Yu T, Xia M, Peng J. Serum hepatitis B core antibody levels predict HBeAg seroconversion in chronic hepatitis B patients with high viral load treated with nucleos(t)ide analogs. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11:469–477. | ||

Xue X, Cai S. Comment on “Assessment of Liver Stiffness in Pediatric Fontan Patients Using Transient Elastography”. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;2016:9343960. | ||

Cai S, Ou Z, Liu D, et al. Risk factors associated with liver steatosis and fibrosis in chronic hepatitis B patient with component of metabolic syndrome. United European Gastroenterol J. 2018;6(4):558–566. | ||

Xiao YB, Cai SH, Liu LL, Yang X, Yun JP. Decreased expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha indicates unfavorable outcomes in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:1781–1789. | ||

Zeng J, Cai S, Liu J, Xue X, Wu X, Zheng C. Dynamic Changes in Liver Stiffness Measured by Transient Elastography Predict Clinical Outcomes Among Patients With Chronic Hepatitis B. J Ultrasound Med. 2017;36(2):261–268. | ||

Chi H, Japhary A, de Man RA, de Knegt RJ, Janssen HLA, Hansen BE. Younger age and language barriers are associated with nonadherence to clinical follow-up in hepatitis B treatment. J Viral Hepat. 2018;25(10):1216–1219. | ||

Xu K, Liu LM, Farazi PA, et al. Adherence and perceived barriers to oral antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis B. Glob Health Action. 2018;11(1):1433987. | ||

Boglione L, Cardellino CS, De Nicolò A, Cariti G, Di Perri G, D’Avolio A. Different HBsAg decline after 3 years of therapy with entecavir in patients affected by chronic hepatitis B HBeAg-negative and genotype A, D and E. J Med Virol. 2014;86(11):1845–1850. | ||

Jeng WJ, Chen YC, Liaw YF. Great and rapid HBsAg decline in patients with on-treatment hepatitis flare in early phase of potent antiviral therapy. J Viral Hepat. 2018;25(4):421–428. | ||

Yang SC, Lu SN, Lee CM, et al. Combining the HBsAg decline and HBV DNA levels predicts clinical outcomes in patients with spontaneous HBeAg seroconversion. Hepatol Int. 2013;7(2):489–499. | ||

Demirtürk E, Hacıhasanoğlu Aşılar R. The effect of depression on adherence to antihypertensive medications in elderly individuals with hypertension. J Vasc Nurs. 2018;36(3):129–139. | ||

Kang AW, Dulin A, Nadimpalli S, Risica PM. Stress, adherence, and blood pressure control: A baseline examination of Black women with hypertension participating in the SisterTalk II intervention. Prev Med Rep. 2018;12:25–32. | ||

Mirzababaei A, Khorsha F, Togha M, Yekaninejad MS, Okhovat AA, Mirzaei K. Associations between adherence to dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet and migraine headache severity and duration among women. Nutr Neurosci. 2018:1–8. | ||

Carmody TP, Fey SG, Pierce DK, Connor WE, Matarazzo JD. Behavioral treatment of hyperlipidemia: techniques, results, and future directions. J Behav Med. 1982;5(1):91–116. | ||

Karr S. Epidemiology and management of hyperlipidemia. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(9 Suppl):S139–S148. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.