Back to Journals » Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management » Volume 15

Photosensitivity reactions in the elderly population: questionnaire-based survey and literature review

Authors Korzeniowska K, Cieślewicz A , Chmara E, Jabłecka A, Pawlaczyk M

Received 10 May 2019

Accepted for publication 24 July 2019

Published 12 September 2019 Volume 2019:15 Pages 1111—1119

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S215308

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Garry Walsh

Katarzyna Korzeniowska,1 Artur Cieślewicz,1 Ewa Chmara,1 Anna Jabłecka,1 Mariola Pawlaczyk2

1Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Poznań 61-848, Poland; 2Department of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Poznań 60-781, Poland

Correspondence: Artur Cieślewicz

Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Długa 1/2 Street, Poznań 61-848, Poland

Tel +48 61 854 9216

Fax +48 61 853 3161

Email [email protected]

Purpose: Older people are at risk of developing adverse drug reactions, including photosensitivity reactions. Therefore, the aim of the study was to assess the use of potentially photosensitizing medications and photoprotection in the elderly population.

Patients and methods: Three hundred and fifty-six respondents (223 [63%] women and 133 [37%] men) aged ≥65 years filled in the original questionnaire concerning photosensitivity reactions to drugs. The diagnosis of drug-induced photosensitivity was based on medical history and clinical examination.

Results and conclusion: We found that drugs potentially causing phototoxic/photoallergic reactions comprised more than one fifth of all drugs used by the participants. The most numerous group was patients treated with 3–5 drugs potentially causing phototoxic/photoallergic reactions simultaneously. Of all drugs, ketoprofen was found to cause the highest number of photosensitivity reactions. Cutaneous adverse reactions were also observed for hydrochlorothiazide, atorvastatin, simvastatin, telmisartan, and metformin. Moreover, it was found that the incidence of photosensitivity reactions can be significantly reduced by using proper photoprotection.

Keywords: photoprotection, elderly population, photosensitivity, phototoxicity, photoallergy

Introduction

Cutaneous adverse drug reactions have been observed in 2%–3% of hospitalized patients. The elderly are a particularly vulnerable group, considering the aging of skin, polypharmacy and inappropriate prescribing, and age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics.1–4

Photosensitivity is an adverse effect caused when a patient using phototoxic or photoallergic drug is exposed to light. Exposure to UVA spectrum results in generation of free radicals (phototoxic reaction) or changes the drug structure into a form causing immune response (photoallergic reaction). Several hundred drugs have been associated with photosensitivity reactions so far, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), cardiovascular drugs (eg, antihypertensives, antiarrhythmics, diuretics), central nervous system (CNS) drugs (eg, neuroleptics, antidepressants), antibiotics, anticancer drugs, and retinoids. Photosensitivity reactions can be divided into phototoxicity and photoallergy. Phototoxic reactions have high incidence,5 require large amounts of drug and progress fast – the symptoms appear within minutes or hours after exposure and include lesions in the sun-exposed areas, with erythema, edema, blisters, exudates and desquamation, followed by the possible additional delayed hyperpigmentation. Photoallergic reactions have much lower incidence (type IV immune response to light-activated compound is necessary), require smaller doses of drug, and manifest after a longer period of time – the symptoms usually become visible in 24–72 hours after exposure and include pruritic eczematous eruption, erythema, vesicles, lichenification, and scaling. The lesions can also spread to skin areas unexposed to sunlight.6–12

Aim of the study

The aim of the study was to assess the use of potentially photosensitizing medications and photoprotection in an elderly population.

Materials and methods

The study was undertaken in compliance with the current laws of Poland, and the Committee for Bioethics of the Poznan University of Medical Sciences gave consent for carrying out the examinations (No 727/17). All subjects provided written informed consent prior to participation, in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was carried out in a group of 365 questionnaire respondents from Wielkopolska Region, aged ≥65 years (Figure 1). The participants were recruited from outpatient clinics, pharmacies, and during educational meetings for geriatric patients. The participation in the survey was voluntary – potential respondents were asked whether they were willing to fill in the questionnaire. An original questionnaire was prepared, with questions concerning pharmacotherapy (including the number and frequency of the use of potentially phototoxic/photoallergic drugs: cardiovascular, oral antidiabetic, systemic and local NSAIDs, drugs affecting the CNS). The questionnaire also included questions about photoprotection and information provided to elderly people by physicians and pharmacists about sun protection during treatment. Additional data obtained from the respondents concerned the amount of time spent outside during spring and summer and the type of medical advice they adhered to in relation to applied pharmacotherapy. Inclusion criteria were: age ≥65 years, the use of at least one potentially photosensitizing drug, at least 2 hours' exposure to the sun in the spring and summer, functional ability to perform physical activity (eg, walking, working in the garden, other forms of outdoor activities), capability to answer the survey without assistance. Exclusion criteria were: history of cancer, previous or ongoing chemotherapy, known allergic cutaneous reactions not caused by drugs (eg, cosmetics, plants), ongoing antibiotic therapy. Cutaneous photosensitivity reactions were confirmed by a dermatologist. The diagnosis of drug-induced photosensitivity was based on medical history, and clinical examination. Patients presented with sun-burn like erythema or eczematous lesions after exposure to the sun's radiation. After detailed analyses of all drugs used, the one suspected to have caused the reaction was discontinued and replaced by other medication after consultation with a specialist or general practitioner. No additional photopatch tests with medication or measurements of minimal erythema dose were performed as no recurrence had been observed.

|

Figure 1 Design of the study. |

Statistical analysis was carried out with Statsoft’s Statistica 12.0 software. Average values and SDs were calculated with descriptive statistics module. Shapiro-Wilk test was used to check the normality of distribution. Statistical significance was calculated using Student’s t-test for independent samples (variables with normal distribution) or Mann-Whitney U test (variables with abnormal distribution). Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used to test linear dependance level between compared variables. Pearson’s chi-squared test was used to assess association between applied photoprotecion and number of adverse skin reactions. All hypotheses were verified using α=0.05.

Results

Three hundred and fifty-six patients (out of 561 subjects screened) were recruited for the study. The participants’ age was between 65 and 98 years; the average age was 72±7 years. Women constituted a larger group (223 [63%] vs 133 [37%] participants).

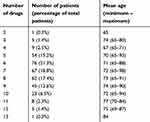

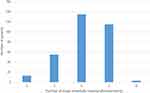

More than half of the respondents were taking 5–9 drugs concomitantly (Table 1). In all cases, at least two agents were drugs that could potentially cause photosensitivity reaction (Figure 2). A statistically significant difference was found between respondents aged 65–74 years and >75 years according to the number of drugs taken simultaneously (7±2 drugs vs 8±2 drugs respectively; p=0.0003). Drugs potentially causing photosensitivity reactions accounted for 22.4% of total drugs used by patients (Table 2). Thirty-six cutaneous photosensitivity reactions were observed and the majority of them was caused by cardiovascular drugs and NSAIDs. Of all potentially photosensitizing substances, ketoprofen was the most common reason for photosensitivity among the studied subjects: it was responsible for adverse reactions observed in 22 out 79 (27.9%) respondents using it, and caused 61.1% of observed photosensitivity reactions (Table 3).

|

Table 1 The distribution of patients according to the number of drugs taken simultaneously |

|

Figure 2 The number of potentially photosensitizing drugs used by the patients. |

|

Table 2 Drug types used by 356 participants of the study |

|

Table 3 Drugs potentially causing phototoxic/photoallergic reactions used by 356 participants of the study |

Almost 60% of the respondents declared that they never used any photoprotection (provided by cosmetics with UV filter; Table 4). More than half of respondents did not receive any information from a physician or pharmacist about the need for photoprotection during treatment with potentially phototoxic/photoallergic drug prescribed. The use of sun-protecting creams was found to be inversely associated with the number of photosensitivity reactions: the patients who did not use any photoprotection had a significantly higher number of adverse reactions compared to patients always applying photoprotection, or using it during spring and summer (no photosensitivity reactions observed in the group of 32 respondents always using photoprotection, ten photosensitivity reactions in the group of 114 respondents using photoprotecion only in spring and summer, and 44 photosensitivity reactions in the group of 210 respondents that did not use any photoprotecion; Pearson’s chi-squared 14.8063; p=0,000609).

|

Table 4 Use of photoprotection by the respondents |

Discussion

The development of medicine has contributed to a significant extension of life, and thus a significant increase in the population of older people. An especially significant increase in the number and proportion of people aged 65 and more has been observed in developed countries. In 1990, the number of Polish people aged ≥65 was 3.873 million, accounting for 10.2% of the whole population. The number increased in 2017 to 6.520 million (17% of the population). Among the elderly population, the majority (59%) are women. Their proportion even increases with subsequent age groups: eg, in the group aged 65–69, the proportion of women is 55%; this increases to 58% at age group 70–74, 62% at age group 75–79, 66% at age group 80–84, and 72% at age group 85 and more. Our studied population consisted of people aged 65–98; women accounted for 63%. Characteristic for this age group is the occurrence of multiple morbidities (such as cardiovascular disorders and metabolic syndromes) and chronic pain.13,14 As a result, a significant part of the population has to take large amounts of medicine, some of which may result in photosensitivity reactions.

Cardiovascular drugs

Cardiovascular diseases are one of the most common disorders affecting the elderly. In our population, hypertension, heart failure, ischemic heart disease, hyperlipidemia, arrhythmia, myocardial infarction, and thromboembolism were observed. As a result, cardiovascular drugs were used by all participants.

Diuretics are one of the basic groups of drugs used in everyday practice, especially among the elderly. The main indications for their use are cardiovascular diseases (hypertension, heart failure), but also liver cirrhosis and kidney diseases. Thiazides (eg, hydrochlorothiazide) and thiazide-like diuretics (eg, indapamide) are effective antihypertensive drugs.15,16 However, they can result in photosensitivity reactions, with hydrochlorothiazide being the most photosensitizing.7 The first cases of hydrochlorothiazide photosensitivity reactions were described in the half of the 20th century, a few years after the drug became available, and included lichen planus-like eruption in light-exposed areas.17 A recent study of Gómez-Bernal et al described 62 cases of thiazide-induced photosensitivity, showing that hydrochlorothiazide was the most common cause of this reaction. Similar results were observed in our study.18 Hydrochlorothiazide was also found to increase the risk of squamous cell carcinoma and malignant melanoma.19 Hydrochlorothiazide was recently associated with increased risk of non-melanoma skin cancer; therefore, patients should reduce sun exposure.20 Thiazide-like diuretics may also lead to photosensitivity reactions (eg, photo-onycholysis was described as a photosensitivity reaction to indapamide), however no such cases were observed in our study.21 Loop diuretics (eg, furosemide, torasemide) can increase the volume of the venous placenta even before the diuretic effect, what makes them very effective in the treatment of heart failure exacerbation.22 Light-induced adverse reactions include bullae in light-exposed areas, observed at high doses of furosemide, 0.5–2 g daily.23 A photoallergic reaction was also described in a patient after taking torasemide, resulting in persistent cutaneous eruption, 2 weeks after torasemide therapy was started.24

Drugs acting on renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), and aldosterone antagonists are widely used in the treatment and secondary prevention of cardiovascular diseases.13 Photosensitivity reactions have been described for many ACEIs, including enalapril (erythematous and eczematous plaques, desquamative rash with fissuring and lichenification, erythematous and scaling rash), captopril (follicular mucinosis), ramipril (edema, erythema, and eczema), and perindopril (eczema on sun-exposed skin areas).25–28 No such reactions were noted in our study. Similar to ACEIs, ARBs have also been associated with photosensitivity reactions.29 One of the first reports on valsartan photosensitivity was a 71 year old woman who presented with pruritic rash on sun-exposed areas after 3-month valsartan therapy.30 Other potentially phototoxic/photoallergic ARBs include olmesartan, candesartan, and telmisartan.29 In our study, dermatitis was observed in two patients taking telmisartan; however hydrochlorothiazide was used concomitantly in both cases.

Calcium channel blockers are effective for the treatment of hypertension in the elderly.31 Telangiectasia of photoexposed body parts (most frequently the face) is a photosensitivity reaction that may result after amlodipine, nifedipine, felodipine, and diltiazem. The effect usually disappears a few months after drug discontinuation. Calcium channel blockers have also been associated with erythema, maculopapular rash, photodistributed hyperpigmentation or lichenoid eruptions. In our study, no such reactions were observed.32–34

Hyperlipidemia is one of the most important cardiovascular risk factors in the world. Therefore, antihyperlipidemic therapies are common, especially in the elderly. Cholesterol-lowering drugs may result in chronic actinic dermatitis, erythema, and eczematous, lichenoid photosensitivity. Atorvastatin was the most commonly used antihyperlipidemic by our patients, and was responsible for photosensitivity reactions which manifested as dermatitis. Erythema was also reported in patients taking simvastatin. No reactions were observed in patients on rosuvastatin.7,35–39

An antihyperlipidemic – fenofibrate, has been described to cause photosensitivity reactions, including erythematous papulovesicles, pruritic, erythematous to violaceous papules, and plaques and lichenoid photodermatitis, but we did not observe such lesions in our patients.40,41

Other cardiovascular drugs that may cause photosensitivity reactions include antiarrhythmics. Photosensitivity reactions after amiodarone may occur even during winter time and include erythema, stinging, sunburn, pseudoporphyria or hyperpigmentation. Higher doses of drug may result in urticarial and edema.42

Another antiarrhythmic – dronaderon, resulted in diffuse erythematous eruption on photoexposed skin areas.43

Antidiabetic drugs

Diabetes mellitus has become a serious problem, especially in the elderly population, due to increasing prevalence and more frequent complications.44,45

According to the data of Statistics Poland, there are more than 2.13 million diabetic Polish people aged >15 years.46 Of our respondents, 28.1% were diabetic patients.

Photosensitivity reactions were observed only in patients on metformin and manifested as erythema. This is quite an interesting observation as metformin is not considered a photosensitizing drug. Similar symptoms have been previously reported in only one paper. Kastalli et al presented three cases with eczematous or erythematous lesions in sun-exposed areas after using metformin. Eruptions healed after discontinuation of metformin.47

In vitro and experimental studies revealed a phototoxic effect associated with glipizide: UV light exposure resulted in loss of cell culture forming ability and induction of induced edema or ulceration followed by increase in skin-fold thickness in mice.48

Drugs affecting the CNS

According to WHO, more than 20% of patients over 60 years have mental and neurological health problems, with dementia and depression being the most common.

Seventy-five percent of our patients took drugs affecting the CNS, mainly due to depression, seizures, stupor, anxiety disorders, sleep disorders, Alzheimer's disease, and Parkinson's disease. Despite potential phototoxicity/photoallergy associated with ten drugs, no such reactions were observed in our study.

Photosensitivity is rarely observed in patients using tricyclic antidepressants. For example, photodistributed erythema and slate-gray hyperpigmentation have been observed in a few cases of photosensitivity after using amitriptyline. Although there were cases of photodistributed erythematous reactions after selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, these are generally not considered potent photosensitizers.7,49 Other photosensitivity reactions associated with antidepressants include photodistributed erythema (after escitalopram, paroxetine, fluoxetine, sertraline), subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (after citalopram) and telangiectasia (after venlafaxine).7,50,51

Some neuroleptics may also lead to photosensitivity reactions. Of all phenothiazines, chlorpromazine is most commonly associated with phototoxicity/photoallergy, resulting in hyperpigmentation of sun-exposed skin fragments.7 Cases of allergic dermatitis and actinic reticuloid after chlorpromazine have also been described.52 Other neuroleptics include clozapine and olanzapine, which were described to cause erythema and photo-onycholysis.53,54

Among benzodiazepines, alprazolam was found to cause photodistributed pruritic erythema.7

NSAIDs

Sixty-five percent of our patients were using analgesic therapy. This is consistent with the fact that chronic pain affects approximately 50% of patients older than 65 years, which leads to increased use of various pharmaceutical forms of analgesics (most commonly NSAIDs and acetaminophen) by these patients.55

The majority of these drugs (ketoprofen, naproxen, tiaprofenic acid, ibuprofen, diclofenac, piroxicam, celecoxib) have been described as causing photoallergy and phototoxicity, with ketoprofen being the most frequently associated with cutaneous photosensitivity reactions. Skin reactions include edema, bullae, dermatitis, erythema multiforme, dyshidrosis, scattered erythematous papules, and vesicles on the face and dorsum of the hands. Diclofenac has also been reported to cause phototoxic fingernail onycholysis.7,42,56–60

Despite the fact that diclofenac was the most commonly used NSAID in our study, no photosensitivity reactions were observed. No such reactions were observed for ibuprofen and naproxen either. On the other hand, ketoprofen was the most frequent cause of photosensitivity, which manifested as dermatitis or erythema. Oral ketoprofen is available in Poland as an over-the-counter drug, which may contribute to increased risk of adverse effects (eg, patients taking the oral and topical form of the drug simultaneously). There have been reported cases of photodermatitis caused by systemic ketoprofen in patients with adverse reactions to the topical form of the drug.61

Photoprotection

Our results confirmed that using sun care products with UV filter provided significant protection from photosensitivity reactions. Minimal sun protection factor (SPF) should be 15, however the dermatologists recommend using creams with SPF =30 or higher. Effective sun-protective cosmetics should also provide water-resistance. More than half of our respondents did not use creams with a filter, probably because they considered that the use of protective clothing (such as long-sleeved shirts, pants, broad-brimmed hats) provides enough photoprotection.62,63

Physicians should encourage patients to use photoprotection, considering the fact that 8% of cutaneous adverse drug reactions are the result of drug-induced photosensitivity and more than 300 drugs have been described as potentially photosensitizing so far. On the other hand, it should be noted that benzophenones or octocrylenes present in cosmetics, as well as some plant extracts, may also cause photosensitivity reactions.7,42

Conclusion

Based on the results of our study, potentially phototoxic/photoallergic drugs constitute more than one fifth of all drugs used by the elderly population. The most numerous group of respondents was taking 3–5 potentially phototoxic/photoallergic drugs simultaneously, with cardiovascular drugs and NSAIDs being the most common. It was also noted that ketoprofen was associated with the highest incidence of photosensitivity reactions. Moreover, the incidence of photosensitivity reactions can be significantly reduced by using proper photoprotection. Future studies should focus on comparing the data obtained from a younger population (<65 years old) and the elderly.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Marzano AV, Borghi A, Cugno M. Adverse drug reactions and organ damage: the skin. Eur J Intern Med. 2016;28:17–24. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2015.11.017

2. Heng YK, Lim YL. Cutaneous adverse drug reactions in the elderly. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;15(4):300–307. doi:10.1097/ACI.0000000000000181

3. Lavan AH, Gallagher P. Predicting risk of adverse drug reactions in older adults. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2016;7:11–22. doi:10.1177/2042098615615472

4. Brahma DK, Wahlang JB, Marak MD, Sangma MC. Adverse drug reactions in the elderly. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2013;4:91–94. doi:10.4103/0976-500X.110872

5. Lugović L, Situm M, Ozanić-Bulić S, Sjerobabski-Masnec I. Phototoxic and photoallergic skin reactions. Coll Antropol. 2007;Suppl 1:63–67.

6. Lugović-Mihić L, Duvančić T, Ferček I, Vuković P, Japundžić I, Ćesić D. Drug-induced photosensitivity - a continuing diagnostic challenge. Acta Clin Croat. 2017;56(2):277–283. doi:10.20471/acc.2017.56.02.11

7. Monteiro AF, Rato M, Martins C. Drug-induced photosensitivity: photoallergic and phototoxic reactions. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34(5):571–581. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.05.006

8. Ibbotson SH. Shedding light on drug photosensitivity reactions. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176(4):850–851. doi:10.1111/bjd.15449

9. Śpiewak R. The substantial differences between photoallergic and phototoxic reactions. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2012;19(4):888–889.

10. Quinero B, Miranda MA. Mechanisms of photosensitization induced by drugs: a general survey. Ars Pharm. 2000;41:27–46.

11. Khandpur S, Porter RM, Boulton SJ, Anstey A. Drug-induced photosensitivity: new insight into patomechanism and clinical variation through basic and applied science. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:902–909. doi:10.1111/bjd.14935

12. Zaheer MR, Gupta A, Iqbal J, et al. Molecular mechanisms of drug photodegradation and photosensitization. Curr Pharm Des. 2016;22(7):768–782. doi:10.2174/1381612822666151209151408

13. Stańczak J, Znajewska A. Population. Size and Structure and Vital Statistics in Poland by Territorial Division in 2018. As of June, 30. Warsaw: GUS; 2018.

14. Ludność w wieku 60+. Struktura demograficzna i zdrowie. [Population aged 60+. Demographic structure and health]. Available from: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/ludnosc/ludnosc/ludnosc-w-wieku-60-struktura-demograficzna-i-zdrowie,24,1.html. Accessed Jul 17, 2019. Polish.

15. Orkaby AR, Rich MW. Cardiovascular screening and primary prevention in older adults. Clin Geriatr Med. 2018;34(1):81–93. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2017.08.003

16. Kithas PA, Supiano MA. Hypertension in the geriatric population: a patient-centered approach. Med Clin North Am. 2015;99(2):379–389. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2014.11.009

17. Harber LC, Lashinsky AM, Baer RL. Skin manifestations of photosensitivity due to chlorothiazide and hydrochlorothiazide. J Invest Dermatol. 1959;33:83–84. doi:10.1038/jid.1959.126

18. Gómez-Bernal S, Alvarez-Pérez A, Rodríguez-Pazos L, Gutiérrez-González E, Rodríguez-Granados MT, Toribio J. Photosensitivity due to thiazides. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105(4):359–366. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2013.01.010

19. Jensen AØ, Thomsen HF, Engebjerg MC, Olesen AB, Sørensen HT, Karagas MR. Use of photosensitising diuretics and risk of skin cancer: a population-based case-control study. Br J Cancer. 2008;99(9):1522–1528. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6604686

20. Pedersen SA, Gaist D, Schmidt SAJ, Hölmich LR, Friis S, Pottegård A. Hydrochlorothiazide use and risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer: a nationwide case-control study from Denmark. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(4):673–681. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.042

21. Rutherford T, Sinclair R. Photo-onycholysis due to indapamide. Australas J Dermatol. 2007;48:35–36. doi:10.1111/j.1440-0960.2007.00324.x

22. Pellicori P, Cleland JG, Zhang J, et al. Cardiac dysfunction, congestion and loop diuretics: their relationship to prognosis in heart failure. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2016;30(6):599–609. doi:10.1007/s10557-016-6697-7

23. Heydenreich G, Pindborg T, Schmidt H. Bullous dermatosis among patients with chronic renal failure on high dose frusemide. Acta Med Scand. 1977;202:61–64.

24. Byrd DR, Ahmed I. Photosensitive lichenoid reaction to torsemide-a loop diuretic. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72(10):930–931. doi:10.1016/S0025-6196(11)63363-6

25. Sánchez-Borges M, González-Aveledo LA. Photoallergic reactions to angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(5):621–622. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03755.x

26. Pérez-Ferriols A, Martínez-Menchón T, Fortea JM. Follicular mucinosis secondary to captopril-induced photoallergy. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2005;96:167–170.

27. Wagner SN, Welke F, Goos M. Occupational UVA-induced allergic photodermatitis in a welder due to hydrochlorothiazide and ramipril. Contact Dermatitis. 2000;43(4):245–246.

28. Le Borgne G, Leonard F, Cambie MP. UVA photosensitivity induced by perindopril (Coversyl®): first reported case. Nouvelles Dermatologiques. 1996;15(5):378–380.

29. Viola E, Coggiola Pittoni A, Drahos A, Moretti U, Conforti A. Photosensitivity with angiotensin II receptor blockers: a retrospective study using data from VigiBase(®). Drug Saf. 2015;38(10):889–894. doi:10.1007/s40264-015-0323-7

30. Frye CB, Pettigrew TJ. Angioedema and photosensitive rash induced by valsartan. Pharmacotherapy. 1998;18:866–868.

31. Caballero-Gonzalez FJ. Calcium channel blockers in the management of hypertension in the elderly. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 2015;12(3):160–165.

32. Ioulios P, Charalampos M, Efrossini T. The spectrum of cutaneous reactions associated with calcium antagonists: a review of the literature and the possible etiopathogenic mechanisms. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:6.

33. Bakkour W, Haylett AK, Gibbs NK, Chalmers RJ, Rhodes LE. Photodistributed telangiectasia induced by calcium channel blockers: case report and review of the literature. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2013;29:272–275. doi:10.1111/phpp.12054

34. Basarab T, Yu R, Jones RR. Calcium antagonist-induced photo-exposed telangiectasia. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136(6):974–975. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1997.tb03952.x

35. Morimoto K, Kawada A, Hiruma M, Ishibashi A, Banba H. Photosensitivity to simvastatin with an unusual response to photopatch and photo tests. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;33(4):274. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1995.tb00487.x

36. Rodríguez-Pazos L, Sánchez-Aguilar D, Rodríguez-Granados MT, Pereiro-Ferreirós MM, Toribio J. Erythema multiforme photoinduced by statins. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2010;26(4):216–218. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0781.2010.00519.x

37. Sommer M, Trautmann A, Stoevesandt J. Relief of photoallergy: atorvastatin replacing simvastatin. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2015;25(2):138–140.

38. Holme SA, Pearse AD, Anstey AV. Chronic actinic dermatitis secondary to simvastatin. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2002;18:313–314.

39. Marguery MC, Chouini-Lalanne N, Drugeon C, et al. UV-B phototoxic effects induced by atorvastatin. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142(8):1082–1084. doi:10.1001/archderm.142.8.1082

40. Leenutaphong V, Manuskiatti W. Fenofibrate-induced photosensitivity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:775–777.

41. Gardeazabal J, Gonzalez M, Izu R, Gil N, Aguirre A, Diaz-Perez JL. Phenofibrate-induced lichenoid photodermatitis. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 1993;9:156–158.

42. Zuba EB, Koronowska S, Osmola-Mańkowska A, Jenerowicz D. Drug-induced photosensitivity. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2016;24(1):55–64.

43. Ladizinski B, Elpern DJ. Dronaderone-induced phototoxicity. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:946–947.

44. Gual M, Formiga F, Ariza-Solé A, et al.; LONGEVO-SCA registry investigators. Diabetes mellitus, frailty and prognosis in very elderly patients with acute coronary syndromes. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2019. Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1007/s40520-018-01118-x

45. Chentli F, Azzoug S, Mahgoun S. Diabetes mellitus in elderly. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;19(6):744–752. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.167553

46. Piekarzewska M, Wieczorkowski R, Zajenkowska-Kozłowska A. Health Status of Population in Poland in 2014. Warsaw: GUS; 2016. ISBN 978-83-7027-611-9.

47. Kastalli S, El Aïdli S, Chaabane A, Amrani R, Daghfous R, Belkahia C. Photosensitivity induced by metformin: a report of 3 cases. Tunis Med. 2009;87(10):703–705.

48. Selvaag E, Anholt H, Moan J, Thune P. Phototoxicity to sulphonamide derived oral antidiabetics and diuretics. Comparative in vitro and in vivo investigations. In Vivo. 1997;11(1):103–107.

49. Viola G, Miolo G, Vedaldi D, Dall’Acqua F. In vitro studies of the phototoxic potential of the antidepressant drugs amitriptyline and imipramine. Il Farmaco. 2000;55:211–218. doi:10.1016/S0014-827X(99)00116-0

50. Röhrs S, Geiser F, Conrad R. Citalopram-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus - first case and review concerning photosensitivity in selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34(5):541–545. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.03.012

51. Vaccaro M, Borgia F, Barbuzza O, Guarneri B. Photodistributed eruptive telangiectasia: an uncommon adverse drug reaction to venlafaxine. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(4):822–824. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08082.x

52. Giomi B, Difonzo EM, Lotti L, Massi D, Francalanci S. Allergic and photoallergic conditions from unusual chlorpromazine exposure: report of three cases. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50(10):1276–1278. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04613.x

53. Howanitz E, Pardo M, Losonczy M. Photosensitivity to clozapine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1995;56:589.

54. Gregoriou S, Karagiorga T, Stratigos A, et al. Photo-onycholysis caused by olanzapine and aripiprazole. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28:219–220. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e318166c50a

55. Stannard CF, Kalso E, Ballantyne J, eds. Evidence-Based Chronic Pain Management. Singapore: Willey-Blackwell, BMJ Books; 2010.

56. Gutiérrez-González E, Rodríguez-Pazos L, Rodríguez-Granados MT, Toribio J. Photosensitivity induced by naproxen. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2011;27:338–340. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0781.2011.00625.x

57. Yazici AC, Baz K, Ikizoglu G, Kokturk A, Uzumlu H, Tataroglu C. Celecoxib-induced photoallergic drug eruption. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:459–461. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02149.x

58. Bergner T, Przybilla B. Photosensitization caused by ibuprofen. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:114–116. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(92)70018-b

59. Loh TY, Cohen PR. Ketoprofen-induced photoallergic dermatitis. Indian J Med Res. 2016;144(6):803–806. doi:10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_626_16

60. Al-Kathiri L, Al-Asmaili A. Diclofenac-induced photo-onycholysis. Oman Med J. 2016;31(1):65–68. doi:10.5001/omj.2016.12

61. Foti C, Cassano N, Vena GA, Angelini G. Photodermatitis caused by oral ketoprofen: two case reports. Contact Dermatitis. 2011;64:181–183. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2010.01817.x

62. Nakao S, Hatahira H, Sasaoka S, et al. Evaluation of drug-induced photosensitivity using the Japanese Adverse Drug Event Report (JADER) database. Biol Pharm Bull. 2017;40(12):2158–2165. doi:10.1248/bpb.b17-00561

63. Rai R, Shanmuga SC, Srinivas C. Update on photoprotection. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57(5):335–342. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.100472

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.