Back to Journals » Drug Design, Development and Therapy » Volume 10

Pharmacokinetics and relative bioavailability of fixed-dose combination of clopidogrel and aspirin versus coadministration of individual formulations in healthy Korean men

Authors Choi HK, Ghim JL, Shon J, Choi YK, Jung JA

Received 23 March 2016

Accepted for publication 19 April 2016

Published 25 October 2016 Volume 2016:10 Pages 3493—3499

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/DDDT.S109080

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Prof. Dr. Wei Duan

Hyang-Ki Choi,1 Jong-Lyul Ghim,2 Jihong Shon,1,3 Young-Kyung Choi,1 Jin Ah Jung1,3

1Department of Pharmacology, Inje University College of Medicine, Busan, Republic of Korea; 2Department of Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology, Anam Hospital, Korea University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea; 3Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Inje University Busan Paik Hospital, Busan, Republic of Korea

Background: Simultaneous prescription of clopidogrel and low-dose aspirin is recommended for the treatment of acute coronary syndrome because of improvements in efficacy and patient compliance. In this study, the pharmacokinetics of a fixed-dose combination (FDC) of clopidogrel and aspirin was compared with coadministration of individual formulations to clarify the equivalence of the FDC.

Methods: This was a randomized, open-label, two-period, two-treatment, crossover study in healthy Korean men aged 20–55 years. Subjects received two FDC capsules of clopidogrel/aspirin 75/100 mg (test) or two tablets of clopidogrel 75 mg and two capsules of aspirin 100 mg (reference) with a 14-day washout period. Plasma concentrations of clopidogrel, aspirin, and salicylic acid were measured using validated ultraperformance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Bioequivalence was assessed by analysis of variance and calculation of the 90% confidence intervals (CIs) of the ratios of the geometric means (GMRs) for AUClast and Cmax for clopidogrel and aspirin.

Results: Sixty healthy subjects were enrolled, and 53 completed the study. Clopidogrel, aspirin, and salicylic acid showed similar absorption profiles and no significant differences in Cmax, AUClast, and Tmax between FDC administration and coadministration of individual formulations. The GMRs (90% CI) for the Cmax and AUClast of clopidogrel were 1.08 (0.95, 1.23) and 0.93 (0.84, 1.03), respectively. The GMRs (90% CI) for the Cmax and AUClast of aspirin were 0.98 (0.84, 1.13) and 0.98 (0.93, 1.04), respectively. Both treatments were well tolerated in the study subjects.

Conclusion: The FDC of clopidogrel and aspirin was bioequivalent to coadministration of each individual formulation. The FDC capsule exhibited similar safety and tolerability profiles to the individual formulations. Therefore, clopidogrel/aspirin 75 mg/100 mg FDC capsules can be prescribed to improve patient compliance.

Keywords: comparative pharmacokinetics, fixed-dose combination, clopidogrel/aspirin, bioequivalence

Introduction

Dual antiplatelet therapy consisting of aspirin and an adenine diphosphate (ADP) P2Y12 receptor antagonist is recommended as the standard antiplatelet regimen for patients with coronary artery disease.1 Clopidogrel, an ADP P2Y12 receptor antagonist, strongly inhibits formation of thrombosis by impeding platelet binding regardless of the degree of degranulation or blood flow status.2,3 Aspirin has antiplatelet effects by irreversible inhibition of the formation of thromboxane A2 by acetylation of platelet cyclooxygenase, thereby contributing to decreasing the mortality caused by myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular diseases.4 In several studies, combined clopidogrel and aspirin treatment increased platelet aggregation, and this effect was superior to administration of aspirin alone in reducing the incidence of cardiovascular death and nonfatal myocardial infarction or stroke.5 A recent meta-analysis concluded that short-term aspirin in combination with clopidogrel is more effective than monotherapy as a secondary preventive treatment for stroke or transient ischemic attack without increasing the risk of hemorrhagic stroke and major bleeding events.6

In addition, approximately 50% of Asians, including Koreans, have a gene variant that leads to resistance to clopidogrel; therefore, there is a safety issue of thrombus formation.1 However, it is well recognized that low-dose aspirin strongly enhances CYP2C19 enzyme activity and increases drug efficacy in patients having clopidogrel resistance.6

Fixed-dose combination (FDC) formulations have an important role in the management of coronary artery disease. The FDC of aspirin and clopidogrel has increased therapeutic compliance, which is a major factor in the poor outcome of stenting patients for acute coronary syndrome, by simplification of the medical regimen.7 In addition, overall costs can be lowered by decreasing the number of prescriptions, bottles, labels, etc.8 Clopidogrel is rapidly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract, with a maximum concentration (Cmax) of 2 ng/mL at 1.4 hours following administration of clopidogrel 75 mg, and is eliminated with a half-life (t1/2) of 1.7 hours.9 In contrast, enteric-coated formulations of aspirin 100 mg show continuous absorption from the intestine with a time-to-reach Cmax approximately 4 hours, and then the drug is rapidly eliminated with a t1/2 less than 1 hour. Based on these pharmacokinetic properties of the two drugs, there should be little possibility of interaction in the absorption profiles, and their short t1/2 indicates that they are suitable for FDC because both drugs are almost completely eliminated within 12 hours after dosing.

In this study, we compared the pharmacokinetics of clopidogrel, aspirin, and its active metabolite, salicylic acid, in healthy men after administration of an FDC formulation and coadministration of clopidogrel and aspirin.

Subjects and methods

The study protocol and written informed consent form were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Inje University Busan Paik Hospital (IRB Number 11-100). The study was carried out in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2010), the International Conference on Harmonization of Good Clinical Practice, and the current Korean Good Clinical Practice guidelines.10

Subjects

Healthy men aged between 20 and 55 years within 20% of the ideal body weight according to Broca’s formula were enrolled in this study. All subjects were judged to be healthy based on the results of a detailed physical examination, 12-lead electrocardiogram, clinical laboratory tests, and vital signs at the screening. The following exclusion criteria were used: excessive consumption of caffeine (>5 cups/d), cigarettes (>10 cigarettes/d), or alcohol (>30 g of alcohol/d), administration of inducers or inhibitors of drug-metabolizing enzymes including proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) (lansoprazole, omeprazole, pantoprazole, and rabeprazole), rifampicin, carbamazepine, and barbitals within 28 days; history of disease influence on drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (eg, gastrointestinal ulcer, ulcerative colitis, and history of abdominal operation); history of hemorrhagic symptoms and disease; aspartate aminotransferase (AST) or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) exceeding 1.25 times the upper limit of the normal range; total bilirubin exceeding 1.5 times the upper limit of the normal range; prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, and bleeding time extended beyond the normal range; platelet level <150×109/L or >350×109/L; and participation in another clinical study within 90 days prior to the start of the study.

Study design

A randomized, open, two-period, two-treatment, two-sequence crossover study was conducted at the Clinical Trial Center of Inje University Busan Paik Hospital, Busan, Republic of Korea (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01496261). The 60 enrolled subjects were divided into two groups and randomized to one of two sequences (RT, TR) at the beginning of the study at a ratio of 1:1 using a randomization schedule generated using the SAS software (v 9.3; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Each group of 30 subjects was administered the study drugs in consecutive periods with a gap of 3 days between them.

The assigned study drugs were administered orally with 240 mL of water after a 10-hour overnight fast, and subjects continued fasting until 4 hours postdose. Subjects were administered two capsules of clopidogrel/aspirin 75 mg/100 mg FDC (Chong Kun Dang Pharm., Seoul, Republic of Korea) in one period. Subjects were coadministered two tablets of clopidogrel 75 mg (Plavix®; Sanofi-Aventis, Schiltigheim, France) and two capsules of aspirin 100 mg (Astrix®; Boryung Pharm., Seoul, Republic of Korea) in the other period with a 14-day washout period. The length of the washout period was estimated to be greater than seven times the reported t1/2 of clopidogrel, aspirin, and salicylic acid (7.2–7.6, 0.4, and 2.1 hours, respectively).9,11 Blood samples for clopidogrel measurement were collected at preset time intervals of predose and 0.33, 0.67, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 24 hours after dosing. Samples for aspirin measurement were taken predose and 1, 2, 2.5, 3, 3.5, 4, 4.5, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 24 hours after dosing. Whole blood samples (5 mL) collected in EDTA (K2) tubes were centrifuged at 1,800× g for 10 minutes, and plasma samples were transferred to microtubes and stored at −70°C.

Safety assessment

Subjects were asked about the occurrence of any adverse events (AEs) between consent and the last poststudy visit. Physical examinations and clinical laboratory tests were performed before and 24 hours after dosing in each period. Vital signs were monitored before and at 12 and 24 hours after dosing in each period. Subjects who took the study drugs at least once during the study were included in the safety assessment.

Bioanalysis

Concentrations of clopidogrel, aspirin, and the active aspirin metabolite salicylic acid were analyzed using validated ultraperformance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC–MS/MS), ACQUITY UPLC™ System (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). Clopidogrel bisulfate and its internal standard (rac clopidogrel-d4 hydrogen sulfate) and aspirin and salicylic acid and their internal standards (aspirin-d4 and salicylic acid-d4, respectively) were prepared using a 96-well solid-phase extraction plate, Bond Elut®, Plexa 10 mg (Varian, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Detection and quantification were performed using a triple quadrupole tandem mass spectrometer with an electrospray ionization interface in positive mode and multiple reaction monitoring mode. Chromatographic separation of the compounds was accomplished using an ACQUITY UPLC® BEH C18 column (1.7 μm, 2.1×50 mm; Waters) with acetonitrile in 1,000 mL of water containing 0.1% formic acid as the mobile phase.

A full validation of the assay was carried out with respect to selectivity, accuracy, precision, recovery, calibration curve, and stability. The calibration curves for clopidogrel, aspirin, and salicylic acid were linear over ranges of 0.01–20.0 ng/mL, 10.0–2,000 ng/mL, and 100–20,000 ng/mL, respectively, with coefficients of determination (R2) greater than 0.995 for all. The precision and accuracy for clopidogrel were 3.3%–8.8% and 94.7%–104.3%, respectively. The precision for aspirin and salicylic acid were 3.8%–4.4% and 2.5%–3.4%, respectively. The accuracy for aspirin and salicylic acid were 97.3%–100.3% and 99.3%–101.3%, respectively.

Pharmacokinetic analysis

The pharmacokinetic parameters of clopidogrel, aspirin, and salicylic acid were estimated using a noncompartmental method using the WinNonlin software (v 6.1; Pharsight Corp, Mountain View, CA, USA). The below the limit of quantitation values occurring prior to the first measurable concentration were set to zero, and those occurring after the first measureable concentration were not included in the pharmacokinetic analysis. The Cmax and time to Cmax (Tmax) were calculated directly from the concentration–time curve. The area under the plasma concentration–time curve (AUC) from time 0 to 24 hours (AUClast) was calculated according to the linear trapezoidal rule. AUC0–∞ was calculated using the following equation: AUC0–∞ = AUClast + Ct/λz, where Ct is the last observed concentration and λz is the elimination rate constant. The t1/2 was calculated as 0.693/λz. Subjects who completed the study were included in the pharmacokinetic analysis.

Statistical analysis

The log-transformed Cmax and AUClast for clopidogrel, aspirin, and salicylic acid were compared using the average bioequivalence approach. This comparison was performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with effects for sequence, subject within sequence, treatment, and period. Because, for logistical reasons, the two groups were administered the study drugs at different times, group effect was also included as a factor.12 Using ANOVA, the 90% confidence intervals (CIs) of the least-squares geometric means were calculated for Cmax and AUClast. The FDC formulation was considered bioequivalent if the 90% CIs of Cmax and AUClast for clopidogrel, aspirin, and salicylic acid fell within the range of 0.80–1.25.12 To evaluate the difference of Tmax between coadministration and FDC, Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used. All statistical calculations were performed using the SAS software (v 9.3; SAS Institute Inc.).

Results

Subject characteristics

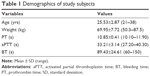

Sixty healthy men (30 subjects per group) were enrolled in the study and randomized. Demographic characteristics of 60 subjects are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the subjects was 25.53 years (range, 21–38 years), and the mean body weight was 69.95 kg (range, 50.3–87.5 kg). Three subjects withdrew consent during the study and four subjects withdrew because of laboratory abnormalities before dosing. Thus, 53 subjects completed this study.

| Table 1 Demographics of study subjects |

Pharmacokinetics

Mean plasma concentration–time profiles of clopidogrel, aspirin, and salicylic acid are shown in Figure 1. Descriptive statistics for the pharmacokinetic parameters of clopidogrel, aspirin, and salicylic acid are provided in Table 2. Similar to the coadministration of clopidogrel and aspirin, the Tmax of clopidogrel and aspirin administered as FDC were 0.67 (P=0.85) and 4.00 hours (P=0.88), respectively. ANOVA indicated a lack of group, period, sequence, and treatment effects for both Cmax and AUClast. The mean t1/2 of coadministered clopidogrel was 6.31 hours, which was comparable with that of FDC clopidogrel at 5.21 hours. The mean t1/2 of aspirin was also similar for coadministration (0.65 hour) and FDC administration (0.63 hour). The 90% CIs for the ratio (FDC/coadministration) of the geometric means for Cmax, AUClast, and AUCinf are presented in Table 3. The mean log-transformed ratios of the primary parameters and their 90% CIs were all within the predefined equivalence limit of 0.80–1.25.

Safety

No serious or significant AEs occurred during the study. A total of six AEs were reported and all were considered mild. There were no AEs related to bleeding or abnormalities in coagulation tests.

Two AEs were reported for one subject (1.67%) after administration of FDC capsules: increases in ALT and AST. Four AEs were reported for three subjects (5% of study population) after coadministration of clopidogrel 75 mg and aspirin 100 mg: an increase in ALT and AST (in the same subject), an increase in blood bilirubin, and catheter site pain. Of these AEs, increases in ALT and AST were considered possibly related to the study drugs and the others were assessed as unlikely to be or definitely not related to the study drugs.

Discussion

The objective of the current study was to compare the pharmacokinetics of a newly developed FDC of clopidogrel 75 mg/aspirin 100 mg with that of coadministration of corresponding doses of clopidogrel and aspirin. Although exposure to clopidogrel can be highly variable with a coefficient of variance over 30%, we applied conventional bioequivalence criteria using a nonreplicative single-dose crossover design because of the narrow therapeutic window and safety issues with clopidogrel.13 Pharmacokinetic analysis showed that the FDC capsule was bioequivalent to the coadministration of the individual drugs.

In practice, clopidogrel is prescribed as a loading dose of 300–600 mg, with 75 mg given subsequently as a maintenance dose. In this study, a single oral dose of 150 mg, half the loading dose, was administered because of the high intraindividual variability in the degree of absorption. Although the aspirin dose of 200 mg is twice the usual maintenance dose (corresponding to 75–100 mg), it was considered acceptable because this was a single-dose study and aspirin shows linear pharmacokinetic characteristics.14

At the time this study was planned, there had been no studies investigating the intraindividual variability of the primary pharmacokinetic parameters of enteric-coated aspirin. Therefore, we calculated the sample size using the ratio of intra- and interindividual variability for the general formulation of aspirin.15 The sample size, based on an estimated intraindividual variability of Cmax for aspirin of 38%, was calculated to be 24 subjects per group to detect a 20% difference between the test and reference treatments with a power of 80% at a significance level of 5%. Thus, 60 subjects were considered sufficient to compare the relative pharmacokinetics of FDC and the coadministration of individual formulations. Our extrapolated intraindividual variability is in agreement with the 36.68% for an enteric-coated formulation of aspirin estimated by Jung et al.16

When we recruited subjects for this study, strict selection criteria were applied for alcohol uptake, smoking status, and other medications that have an effect on the clopidogrel-metabolizing enzyme CYP2C19, because variability in clopidogrel pharmacokinetics has been attributed to alcohol, smoking, CYP2C19 genotype, and genotype-related drug–drug interactions. Clopidogrel is probably converted to ethyl clopidogrel in the presence of ethyl alcohol, the major ingredient of alcoholic beverages, causing a decrease in the total metabolism of clopidogrel. In addition, ethyl alcohol increases the cytotoxic effect of clopidogrel and the pharmacological activity by prolonged presence of clopidogrel by decreasing the total metabolism of clopidogrel (hydrolysis and transesterification) in the presence of ethyl alcohol.17 A potential role of smoking in the metabolism of clopidogrel and high on-treatment platelet reactivity were suggested. Pharmacodynamic studies and post hoc analyses of large clinical trials support a link between smoking status and the efficacy of clopidogrel therapy.18 In addition, clopidogrel is mainly metabolized to its active metabolite by CYP2C19,19 so it is important to consider comedication with drugs having the same metabolic route.

The present study has several limitations. In clinical situations, dual therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin is administered in multiple doses to cardiovascular disease patients of both sexes. However, all participants of this study were healthy men, who may not represent the target patients, and only a single dose of treatment was given. Because the antiplatelet effect of clopidogrel decreases with patient age,20 further multiple dosing studies, preferably in patients with cardiovascular disease, are needed to apply the FDC to clinical practice. Also, pharmacodynamic evaluation was not performed in the current study. Pharmacodynamic responses such as platelet aggregation were more related to clinical outcome than pharmacokinetics.21

Conclusion

The results from the present study indicate that the clopidogrel 75 mg/aspirin 100 mg FDC capsule was bioequivalent to individual formulations of corresponding doses of the two drugs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ji Young Kim of the Clinical Trial Center, Inje University Busan Paik Hospital, Busan, Republic of Korea for contributions to the conduct of the study. The authors also thank BioInfra. Co. Ltd., Seoul, Republic of Korea for assays of the study drugs.

This study was sponsored by Chong Kun Dang Pharmaceutical Corp. Ltd., Seoul, Republic of Korea, and a grant from the Korean Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HI14C1063).

Disclosure

Jihong Shon is currently employed in the US Food and Drug Administration. His contribution to the manuscript was based on his prior employment, and the current manuscript does not necessarily reflect any position of the US Food and Drug Administration or the US government. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;130(25):2354–2394. | ||

Jarvis B, Simpson K. Clopidogrel: a review of its use in the prevention of atherothrombosis. Drugs. 2000;60(2):347–377. | ||

Velders MA, Abtan J, Angiolillo DJ, et al. Safety and efficacy of ticagrelor and clopidogrel in primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart. 2016;102(8):617–625. | ||

Burger W, Chemnitius JM, Kneissl GD, Rucker G. Low-dose aspirin for secondary cardiovascular prevention – cardiovascular risks after its perioperative withdrawal versus bleeding risks with its continuation – review and meta-analysis. J Intern Med. 2005;257(5):399–414. | ||

Terpening C. An appraisal of dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin for prevention of cardiovascular events. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22(1):51–56. | ||

Zhang Q, Wang C, Zheng M, et al. Aspirin plus clopidogrel as secondary prevention after stroke or transient ischemic attack: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;39(1):13–22. | ||

Deharo P, Quilici J, Bonnet G, et al. Fixed-dose aspirin-clopidogrel combination enhances compliance to aspirin after acute coronary syndrome. Int J Cardiol. 2014;172(1):e1–e2. | ||

Wertheimer AI. The economics of polypharmacology: fixed dose combinations and drug cocktails. Curr Med Chem. 2013;20(13):1635–1638. | ||

Caplain H, Donat F, Gaud C, Necciari J. Pharmacokinetics of clopidogrel. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1999;25(Suppl 2):25–28. | ||

Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. Korea Good Clinical Practice Guideline. Chungcheongbuk-do, South Korea: MFDS; 2011. Korean. | ||

Benedek IH, Joshi AS, Pieniaszek HJ, King SY, Kornhauser DM. Variability in the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of low dose aspirin in healthy male volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol. 1995;35(12):1181–1186. | ||

US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: Statistical Approaches to Establishing Bioequivalence. Silver Springs, MD: FDA; 2001. | ||

Zhang H, Lau WC, Hollenberg PF. Formation of the thiol conjugates and active metabolite of clopidogrel by human liver microsomes. Mol Pharmacol. 2012;82(2):302–309. | ||

Dubovska D, Piotrovskij VK, Gajdos M, Krivosikova Z, Spustova V, Trnovec T. Pharmacokinetics of acetylsalicylic acid and its metabolites at low doses: a compartmental modeling. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 1995;17(1):67–77. | ||

Bae SK, Seo KA, Jung EJ, et al. Determination of acetylsalicylic acid and its major metabolite, salicylic acid, in human plasma using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry: application to pharmacokinetic study of Astrix in Korean healthy volunteers. Biomed Chromatogr. 2008;22(6):590–595. | ||

Jung JA, Kim TE, Kim JR, et al. The pharmacokinetics and safety of a fixed-dose combination of acetylsalicylic acid and clopidogrel compared with the concurrent administration of acetylsalicylic acid and clopidogrel in healthy subjects: a randomized, open-label, 2-sequence, 2-period, single-dose crossover study. Clin Ther. 2013;35(7):985–994. | ||

Tang M, Mukundan M, Yang J, et al. Antiplatelet agents aspirin and clopidogrel are hydrolyzed by distinct carboxylesterases, and clopidogrel is transesterificated in the presence of ethyl alcohol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319(3):1467–1476. | ||

Swiger KJ, Yousuf O, Bliden KP, Tantry US, Gurbel PA. Cigarette smoking and clopidogrel interaction. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2013;15(5):361. | ||

Holmes MV, Perel P, Shah T, Hingorani AD, Casas JP. CYP2C19 genotype, clopidogrel metabolism, platelet function, and cardiovascular events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;306(24):2704–2714. | ||

Xhelili E, Eichelberger B, Kopp CW, Koppensteiner R, Panzer S, Gremmel T. The antiplatelet effect of clopidogrel decreases with patient age. Angiology. Epub February 9, 2016. | ||

Maree AO, Fitzgerald DJ. Variable platelet response to aspirin and clopidogrel in atherothrombotic disease. Circulation. 2007;115(16):2196–2207. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.