Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 12

Peer Victimization, Maternal Control, And Adjustment Problems Among Left-Behind Adolescents From Father-Migrant/Mother Caregiver Families

Authors Xiong Y, Wang H, Wang Q , Liu X

Received 12 June 2019

Accepted for publication 30 August 2019

Published 9 October 2019 Volume 2019:12 Pages 961—971

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S219249

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Einar Thorsteinsson

Yuke Xiong, Hui Wang, Quanquan Wang, Xia Liu

Institute of Developmental Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, Beijing Normal University, Beijing 100875, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Xia Liu

Institute of Developmental Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, Beijing Normal University, No. 19 Xinjiekouwai Street, Beijing 100875, People’s Republic of China

Tel + 86 10 135 8166 2331

Fax + 86 10 58806819

Email [email protected]

Background: Left-behind adolescents who are from father-migrant/mother caregiver families have become the main type of left-behind children in China. The migratory of fathers not only makes left-behind adolescents suffer more difficulties but also causes left-behind women to face the challenge of raising the child alone. This study examined the association among peer victimization, maternal psychological control, and adjustment problems among Chinese rural left-behind adolescents. Furthermore, we first explored the moderating role of maternal behavioral control in this relationship.

Methods: Using cross-sectional design, we recruited 194 left-behind adolescents (49% girls; mean age = 13.51, SD = 1.03) from four junior schools in the Guizhou province of China. Left-behind adolescents completed a battery of self-report questionnaires regarding peer victimization, maternal control, self-injury behaviors, depression, and loneliness.

Results: The hierarchical multiple regressions indicated that both peer victimization and maternal psychological control were positively associated with self-injury behaviors, depression, and loneliness. Moreover, maternal behavioral control played a dual role in the impact of peer victimization on self-injury behaviors depending on the levels of maternal psychological control. When left-behind women exerted high psychological control on their children, maternal behavioral control buffered the negative effect of peer victimization on self-injury behaviors. However, when left-behind women exerted low psychological control on their children, maternal behavioral control exacerbated the negative effect of peer victimization on self-injury behaviors.

Conclusion: These findings suggest that the effectiveness of behavioral control may depend on different situations, left-behind women should be cautious in exerting behavioral control over their children.

Keywords: left-behind adolescents, peer victimization, psychological control, behavioral control, psychological adjustment

Introduction

With the rapid urbanization and increasing economic development in China, a great number of migrant workers leave their hometown for major cities in search of better jobs. Due to financial limitations, most of rural-to-urban migrant workers have to leave their children in the countryside. According to the investigation of All-China Women’s Federation,1 over 61 million children, accounting for one-fifth of the nation’s children, have been left behind by one or both their migratory parents. More than half of the left-behind children are left behind by single parent, and 82% of them are from father-migrant/mother caregiver families.2 Although father-migrant/mother caregiver is the best strategy for rural families to seek a livelihood, it further creates an unusual conjugal relationship and an incomplete family structure.3 Under such situation, left-behind women shoulder the burden of raising children alone, while left-behind adolescents lack the emotional support and supervision from their fathers.

Peer victimization is the experience among children of being a target of the aggressive behavior of other children.4 Numerous studies have shown that peer victimization is concurrently associated with a range of adjustment difficulties, including non-suicidal self-injury behaviors,5 depression,6 and loneliness.7 What’s more, the negative effects of peer victimization can persist until adulthood, which throws a long shadow over affected people’s lives.8,9

Given the existing literature documenting the negative effects of peer victimization on development, an important question to ask concerns the extent to which peer victimization is associated with adjustment problems among left-behind adolescents. This question is particularly salient as left-behind adolescents are more vulnerable to be the victims of bullying by others in comparison to their counterparts because of the absence of parents.10–12 To our knowledge, only one study has examined this link and found that peer victimization was a significant predictor of left-behind adolescent depression, panic symptoms, and severe psychological distress.12 However, this study only explored the relationship between peer victimization and emotional problems, the negative effects of peer victimization on adolescent behavioral outcomes are still unclear. In order to better understand the link between peer victimization and psychosocial adjustment, the present study aims to examine the impact of peer victimization on both emotional and behavioral adaptation among Chinese left-behind adolescents.

Parental control is an important parenting behavior in the socialization of adolescents,13 which can be separated into two distinct forms: psychological and behavioral.14 Psychological control is defined as parental attempts to control the psychological world of their child via guilt-induction, love withdrawal, and manipulations of the attachment bond with the child.14 An array of prior researches indicated that psychological control was clearly and consistently associated with adverse outcomes for the child, such as depressive symptoms,15,16 loneliness,17 and externalizing problems.18 Self-determination theory (SDT) can aid in understanding why psychological control is a problematic parenting practice.19,20 According to the SDT, psychological control restricts and violates children’s basic psychological needs for experiencing autonomy, relatedness, and competence, which hampers adolescent emotional and social development. Besides, stress might prompt increased use of parental psychological control because of parents’ need to protect their children from environmental risks by controlling their behaviors and surroundings.19 Left-behind women are under high pressure such as raising children and productive labor as a result of the migration of their husbands.3 Stressful conditions could thus make left-behind women more inclined to use psychological control to manipulate children’s thoughts and behaviors. However, few studies explore the relationship between maternal psychological control and maladaptation among left-behind adolescents. Another aim of the current study, therefore, is to examine the negative impact of maternal psychological control on left-behind adolescents’ adjustment.

In contrast, behavioral control refers to the provision of regulation or structure on the child’s behavioral world via expectations, guidelines, and restrictions.14,21 The effectiveness of behavioral control, however, has been a topic of scientific debate. Some researchers hold that parental guidance and monitoring is crucial because adolescents are still not fully mature.22 Empirical studies have found that behavioral control was often associated with positive outcomes for adolescents, including less problem behaviors,23,24 higher academic function,25 and lower depressive symptoms.26 Whereas others believe behavioral control may be ineffective or even counter-effective, because adolescents typically develop a growing desire for autonomy and may perceive behavioral control as a form of overprotection or autonomy invasion.27,28 In this regard, longitudinal studies have found that behavioral control did not significantly predict less adolescents’ anti-social behaviors or delinquency over time.29,30

Given the mixed findings of the effectiveness of behavioral control, researchers proposed that the effectiveness of behavioral control may depend on different situations or contexts.31 Relevant research on the role of behavioral control can be broadly divided into family and non-family environments. On the one hand, some studies found that behavioral control played a significant but inconsistent role when considering family environment. For example, research has shown that parental behavioral control led to the perceptions of privacy invasion among adolescents reporting higher quality interactions with parents.32 Furthermore, high levels of parental behavioral control was related to an increase in delinquent activities of adolescents in high support families.33 However, several investigators have found that maternal behavioral control predicted a decrease in adjustment problems when combined with a low level of psychological control.34,35 On the other hand, empirical studies suggested that behavioral control also played a significant but inconsistent role when considering non-family environmental factors. For example, researches indicated that higher levels of behavioral control were more strongly associated with less externalized problems among adolescents who were in more dangerous environments, such as hang out on the street,36 neighborhood disorders,37 and peer victimization.38 However, when adolescents in low socioeconomic status, higher levels of parental control more often co-occurred with higher levels of delinquency.28

Although existing literature has shown that behavioral control did play a significant role in different circumstances, the pattern of the effectiveness of behavioral control was inconsistent under a certain context. One important explanation is that previous studies primarily include a specific environmental factor and few studies examine the role of behavioral control simultaneously take family and non-family factors into consideration. This raises the question of what role behavioral control plays under different environmental factors. Therefore, the last aim of the study is to explore the role of maternal behavioral control on the association between peer victimization and left-behind adolescents’ adjustment problems while considering maternal psychological control.

Purpose of the study

Taken together, the present study seeks to examine the following two questions among left behind adolescents from father-migrant/mother caregiver families in rural China: (a) whether peer victimization and maternal psychological control predict left-behind adolescents’ adjustment problems (indicated by self-injury behaviors, depression, and loneliness); (b) whether maternal behavioral control moderates the relationship among peer victimization, maternal psychological control, and adjustment problems. Based on the existing literature, we hypothesize that both peer victimization and maternal psychological control would positively associate with self-injury behaviors, depression, and loneliness. Moreover, we hypothesize that maternal behavioral control would play a significant moderating role in the relationship between peer victimization and adjustment problems when considering maternal psychological control.

Method

Participants

This is a cross-sectional study conducted in a rural county from Guizhou province, which is a region of China that lots of people migrate in search of work. A total of 667 left-behind adolescents from four junior high schools were recruited to complete the questionnaire survey. We selected 194 left-behind adolescents as participants for the present study according to four inclusion criteria: (a) adolescents’ fathers migrate to make a living and left-behind adolescents are taken care of by their mothers; (b) both parents are alive; (c) parents are not divorced; (d) left-behind adolescents did not have an observable physical or developmental disability. Table 1 provided details regarding the demographic background of the participants.

|

Table 1 Demographic background of study participants |

Procedures

Data collection took place in November 2017. The students completed survey questionnaires that were group-administered in their classrooms after the school granted permission to perform the study. The students were informed that there were no right or wrong answers and were assured of the voluntary and confidential nature of this study. All measures were administered by trained research assistants from the researchers’ university. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Beijing Normal University. Prior to survey administration, the researchers obtained consent forms signed by students and their caregivers.

Measures

Demographic form

Participants completed a brief demographic form that provides background information on age, gender, grade, subjective socioeconomic status, and maternal education level.

Peer victimization

Peer victimization was assessed by a self-report measure from Mynard and Joseph39 and revised by Guo, Chen, Ye, Pan, and Lin40. The 18-item questionnaire measures how often (0 = never, 1 = rarely, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often) children have experienced physical, verbal, relational victimizing experiences and attacks on property during this semester. Physical victimization includes 3 items, for example, “other students beat me up in this semester”; verbal victimization contains 5 items, sample items include, “other students deliberately speak ill of me and spread rumors about me”; relational victimization includes 7 items, such as, “other students intentionally do something to make the teacher dislike me”; property victimization includes 3 items, for example, “other students steal money or something else from me”. The mean of the 18 items was taken, with higher scores indicating greater peer victimization. Validity and reliability of this instrument have been supported previously.40 The confirmatory factor analysis showed that the 4-factor model achieved a good model fit (χ2/df = 3.81, CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.04), indicating the internal validity was good. Moreover, the Omega coefficient was 0.90 in the present study.

Maternal psychological control

Adolescents reported on their mother’s psychological control by responding to an 18-item measure. The scale was developed by Wang, Pomerantz, and Chen25, which has been widely used among Chinese children and adolescents with good reliability and validity.3,41 Ten items taps guilt induction (e.g., “My mother tells me that I should feel guilty when I do not meet her expectations”), five taps love withdrawal (e.g., “My mother avoids looking at me when I have disappointed her”), and three taps authority assertion (e.g., “My mother tells me that what she wants me to do is the best for me and I should not question it”). Children indicated how true each item was of their mother (1 = not at all true; 5 = very true); mean scores were used in the analyses, with higher scores representing greater maternal psychological control. The confirmatory factor analysis showed that the 3-factor model achieved an acceptable model fit (χ2/df = 3.58, CFI = 0.90, TLI = 0.88, RMSEA = 0.06). The Omega coefficient was 0.80 for the present study.

Maternal behavioral control

Maternal behavioral control was measured by a self-report scale from Barber, Stolz, and Olsen42 and revised by Zhao43. The scale measures parental knowledge as a construct of behavioral control, means the extent to which the parents know the behaviors and activities of their children. Each item is rated on a 3-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (do not know) to 3 (know), children reported the degree to which their mothers know their behaviors, such as “my mother knows where I go at night”. The average scores of children’s responses were calculated, with higher values indicating greater maternal behavioral control. The confirmatory factor analysis was conducted and results showed good internal validity (χ2/df = 4.15, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.03). In the present study, the Omega coefficient was 0.80.

Self-injury behaviors

The adolescents’ self-injury behavior was measured by a shortened and modified version of the Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory, which was constructed and validated by Gratz44 and adapted to adolescents by Lundh, Karim, and Quilisch45. In the current nine-item version, children were asked whether they have deliberately engaged in any of nine different kinds of self-injury behaviors during the past 6 months, such as “Deliberately bite my skin”. Children responded to each item by indicating the number of times (1 = never; 5 = five times more) for their self-injury behaviors. Mean scores were used, with higher scores indicating higher levels of self-injury behavior. The results of confirmatory factor analysis indicated an acceptable internal validity (χ2/df = 8.47, CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.89, RMSEA = 0.04). Besides, the Omega was coefficient 0.87 in the present study.

Depression

Children’s depression was measured by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Scale for Children.46 The scale contains 20 items, each of which consists of four possible responses describing a symptom of depression in a manner from never to always. This instrument includes four subscales: (a) depressed affect (e.g., “I feel depressed”), (b) positive affect (e.g., “I was happy”), (c) somatic and retarded activity (e.g., “I did not feel like eating; my appetite was poor”), (d) interpersonal (e.g., “people were unfriendly”). Each participant was directed to choose the sentence that best described him or her in the last week. Scores were computed by averaging items, with higher scores reflecting greater depression. This questionnaire has demonstrated satisfactory reliability and validity in prior research with Chinese adolescents.47 The confirmatory factor analysis showed that the 4-factor model achieved an acceptable model fit (χ2/df = 2.91, CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.05). The Omega coefficient was 0.82 in the present study.

Loneliness

Adolescents’ loneliness was assessed using the Loneliness Rating Scale48 and revised by Li, Zou, and Liu49 in Chinese adolescents. Six items focus on children’s feeling of loneliness were selected, such as “I feel alone”. Adolescents were asked to report their feelings on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (definitely does not apply) to 4 (definitely applies). Items were averaged such that higher scores reflected higher loneliness. The results of confirmatory factor analysis indicated a good internal validity (χ2/df =9.90, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.04). The Omega coefficient was 0.89 in the present study.

Data analyses

All analyses were conducted using SPSS 20.0. First, we conducted preliminary analyses, including independent t-test on gender, correlations, means, and standard deviations for the main variables. Next, a series of hierarchical regression analyses were performed to examine the moderating effect of maternal behavioral control in the relationship among peer victimization, maternal psychological control, and adjustment problem. The adolescents’ gender (0 = girls, 1 = boys) was included as a covariate in the first regression step, to which peer victimization, maternal psychological control, and maternal behavioral control were added as the main predictors in the second step. Then, three two-way interaction terms (peer victimization × maternal psychological control, peer victimization × maternal behavioral control, and maternal psychological control × maternal behavioral control) was added in the third step. Finally, a three-way interaction term (peer victimization × maternal psychological control × maternal behavioral control) was included in the fourth step. For significant interactions, simple slope analysis was conducted. All continuous variables were standardized for all the regression analyses.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Table 2 showed the means and standard deviations of primary study variables separately for left-behind boys and girls. A series of t-tests indicated that girls reported higher levels of maternal behavioral control than boys, and there was no significant gender difference in the peer victimization, maternal psychological control, self-injury behaviors, depression, or loneliness.

|

Table 2 Mean differences between boys and girls on primary study variables |

Correlations among all the study variables were presented in Table 3. As shown, peer victimization was significantly positively correlated with self-injury behaviors, depression and loneliness. Maternal psychological control was positively related to self-injury behaviors, depression, and loneliness. In addition, maternal behavioral control was negatively linked with self-injury behaviors, depression, and loneliness.

|

Table 3 Descriptive statistics and correlations of study variables |

Predicting self-injury behaviors

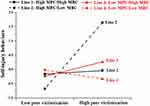

The results of multiple regressions analyses were shown in Table 4. Peer victimization and maternal psychological control significantly and positively predicted self-injury behaviors (β = 0.30, t = 4.98, p < 0.001; β = 0.14, t = 2.40, p < 0.05), showing that higher peer victimization and maternal psychological control were associated with more self-injury behaviors. Besides, there was a significant three-way interaction in predicting self-injury behaviors (β = −0.35, t = −5.85, p < 0.001). Probing this interaction indicated that the positive relationship between peer victimization and self-injury behaviors was significant only for those who reported a) high maternal psychological control and low maternal behavioral control or b) low maternal psychological control and high maternal behavioral control. Specifically, as illustrated in Figure 1, when the level of maternal psychological control was high, peer victimization was associated positively with self-injury behaviors in the condition of low maternal behavioral control (simple slope = 1.01, t = 9.48, p < 0.001, Figure 1. Line 2), however, peer victimization was not significantly associated with self-injury in the condition of high behavioral control (simple slope = 0.08, t = 0.73, p > 0.05, Figure 1. Line 1). When the level of maternal psychological control was low, peer victimization was associated positively with self-injury behaviors in the condition of high maternal behavioral control (simple slope = 0.22, t = 2.05, p < 0.05, Figure 1. Line 3), however, peer victimization was not significantly associated with self-injury behaviors in the condition of low behavioral control (simple slope = −0.13, t = −0.86, p > 0.05, Figure 1. Line 4). Further slope difference testes revealed that the “High MPC/Low MBC” slope differed significantly from the “High MPC/High MBC” slope (t = 6.46, p < 0.001), the “Low MPC/High MBC” slope (t = 5.11, p < 0.001), and the “Low MPC/Low MBC” slope (t = 7.75, p < 0.001), and, which meant the four groups reported similar self-injury behaviors when peer victimization levels were low, whereas the latter three groups exhibited lower self-injury behaviors if peer victimization scores were high. The other three slopes did not differ significantly from each other.

|

Table 4 Summary of the hierarchical multiple regression analyses |

Predicting depression

Table 4 exhibited positive effects of peer victimization and maternal psychological control on adolescent depression (β = 0.39, t = 5.67, p < 0.001; β = 0.27, t = 3.96, p < 0.001), showing that higher peer victimization and maternal psychological control were associated with more depression. There were no significant two-way or three-way interactions predicting left-behind adolescent depression.

Predicting loneliness

As shown in Table 4, peer victimization and maternal psychological control positively predicted left-behind adolescent’s loneliness (β = 0.41, t = 5.49, p < 0.001; β = 0.21, t = 2.76, p < 0.01), showing that higher peer victimization and maternal psychological control were associated with more loneliness. However, there were no significant two-way or three-way interactions predicting left-behind adolescent loneliness.

Discussion

Left-behind adolescents who are from father-migrant/mother caregiver families have become the main type of left-behind children in China. The migratory of fathers not only makes left-behind adolescents suffer more difficulties but also causes left-behind women to face the challenge of raising children alone, which merit researchers’ attention very much. The goal of the current study was to examine the association among peer victimization, maternal psychological control, and adjustment problems in a sample of Chinese rural left-behind adolescents. In addition, the potential moderating role of maternal behavioral control for the relationship was explored. The main findings of our study were discussed below.

Findings lent support for the hypotheses that peer victimization had a direct, negative effect on left-behind adolescent self-injury behaviors, depression, and loneliness. This result extended the findings from prior research12 by showing that peer victimization was not only associated with internalizing symptoms but also externalizing problems. Due to left-behind adolescents’ vulnerability to being the victims of bullying as well as their limited coping resources,10 parents, caregivers and educators should pay attention to left-behind adolescent’s victimization experiences and take appropriate measures to minimize the negative impacts of peer victimization.

Furthermore, our findings revealed maternal psychological control was positively associated with left-behind adolescents’ self-injury behaviors, depression, and loneliness. Self-determination theory posited that psychological control restricted and violated children’s basic needs for autonomy, relatedness, and competence, which led to children’s maladjustment.20 Stressful conditions may create a further burden on parents and lead parents to control their children psychologically,19 especially for left-behind women, who might adopt higher levels of psychological control to interfere with children’s thoughts and behaviors because of extremely parenting pressure caused by the absence of their husband.3 This result indicated that we need to be alert to the adverse effects of maternal psychological control on left-behind adolescents whose fathers migrate. Left-behind women should provide more caring and love for their children by minimizing the use of psychological control.

The most important and valuable finding of our study was the significant interaction among peer victimization, maternal psychological control, and maternal behavioral control on self-injury behaviors among left-behind adolescents. As the three-way interaction suggested, maternal behavioral control played a different role in the impacts of peer victimization on self-injury behaviors depending on the levels of maternal psychological control. This finding was in line with the previous study indicated that monitoring activities may be more or less effective in minimizing maladjustment under different situations or contexts.31

When left-behind women exerted high psychological control on their children, behavioral control acted as a buffer against peer victimization. That is, peer victimization was not significantly associated with self-injury behaviors in the condition of high levels of maternal behavioral control, while peer victimization was positively associated with self-injury behaviors in the condition of low levels of maternal behavioral control. Our results indicated that the effectiveness of maternal behavioral also existed when cumulative risk factors were present (i.e. peer victimization at school and high maternal psychological control at home), which extended previous findings that behavioral control was an effective deterrent of psychosocial problems only when adolescents exposed to single and negative environment, such as peer victimization38 or neighborhood violence.37 One possible explanation of this finding was that parental monitoring and knowledge served as important resilience resources, in which victimized youths with high behavioral control were less likely to involve in self-injury behaviors. Besides, maternal behavioral control could also enhance mothers’ ability to identify and appropriately intervene problematic behaviors among adolescents,38 thus reducing the risk of self-injury behaviors.

However, the buffering effect of behavioral control on peer victimization was disrupted by the low levels of maternal psychological control. When left-behind women exerted low psychological control on their victimized children, behavioral control acted as a risk factor rather than a buffering factor. Specifically, peer victimization was significantly associated with self-injury behaviors in the condition of high levels of maternal behavioral control, while peer victimization was not significantly associated with self-injury behaviors in the condition of low levels of maternal behavioral control. Mothers who showed low psychological control may allow adolescents to experience and express their own thoughts and emotions freely.50 Thus, under less intrusive and controllable family environment, adolescents may highly emphasize their autonomy and reversely perceive maternal behavioral control as a threat to their growing autonomy needs as well as a form of privacy invasion.28,51 According to reactance theory, adolescents experienced psychological reactance when free choice over their own behavior is threatened by external forces,52 which may further lead to adolescent’s maladaptation. Moreover, existing literature demonstrated that high levels of behavioral control could be counter-effective and related to an increase in delinquent activities, especially in a supportive family environment.32,33 Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that when victimized adolescents experienced low maternal psychological control, they were more likely to interpret high maternal behavioral control as autonomy invasion rather than effective protection. As a result, they were at the risk of developing self-injury behaviors to claim their autonomy.

Considering the behavioral control is the management of children’s behaviors and activities, relevant research also has found that behavioral control is related primarily to externalized problems among adolescents.14,42 The present study, therefore, did not find that maternal behavioral control plays a significant role in the association between peer victimization and depression or loneliness among left-behind adolescents with varying levels of psychological control.

Several limitations of the present study were important to note. First, our study used the total scores of peer victimization rather than distinguished the scores of different types of peer victimization. A meta-analytic review suggested that there were unique patterns of associations for each form of victimization with social-psychological adjustment, for example, relational victimization was more strongly related to internalizing problems.53 Future studies, therefore, should separate each form of peer victimization and examine its unique effect on maladjustment among left-behind adolescents. Second, given our samples were from father-migrant/mother caregiver families, the current study did not consider fathers’ parenting practice. However, there would be the possibility that fathers could exert parenting behaviors on their children through long-distance communication such as online video chat and influence children’s development. Future research could examine the effect of father’s control on left-behind adolescents’ adjustment. Third, this study was a cross-sectional design, which limits our ability to make causal statements. Besides, it would be possible that there are reciprocal relationships among peer victimization, maternal psychological control, and maternal behavioral control. Thus, longitudinal studies are needed to firmly establish the causal and reciprocal relationship among those variables. Fourth, we relied solely on adolescents’ self-report to measure maternal psychological and behavioral control. Although it is accepted within the literature that self-reports from children are one of the most valid ways to assess the impact of parental control on adolescents,14 it must be recognized that no confirmation from other information resources (e.g., parents) was sought. It would be ideal to include multiple measures in addition to self-report, such as observational ratings and parents-report, in future studies. Lastly, the samples were recruited from a single geographic region, which limits the generalizability of the results. Future research may want to replicate the results with left-behind adolescents in varying regions.

Despite these limitations, some valuable information and important implications can be derived from our findings. To begin with, our study indicated that both peer victimization and maternal psychological control are prominent risk factors for left-behind adolescents’ self-injury behaviors, depression, and loneliness. Thus, decreasing peer victimization at school and psychological control at home may be very important for reducing adjustment problems among left-behind adolescents. For example, schools should create a harmonious and friendly atmosphere to reduce the prevalence of peer victimization, at the same time, relevant educators should spread the harmfulness of psychological control to left-behind women and help them minimize their use of psychological control. In addition, our findings highlighted the special attention should be paid to the development of left-behind adolescents from father-migrant/mother caregiver families. Although those adolescents are accompanied by their mothers, they still face the threat of peer victimization and suffer the negative impact of mother’s intrusive parenting behaviors.

Moreover, we found the role of maternal behavioral control on the relationship between peer victimization and self-injury has differed across the levels of maternal psychological control. Specifically, when left-behind women exerted high psychological control on their children, maternal behavioral control buffered the negative effect of peer victimization on left-behind adolescents’ self-injury behaviors. However, when left-behind women exerted low psychological control on their children, maternal behavioral control exacerbated the negative effect of peer victimization on left-behind adolescents’ self-injury behaviors. These findings suggested that maternal regulation and monitoring may not be necessary or effective in all situations and left-behind women should be cautious in exerting behavioral control over their children especially when adolescents perceive it as a threat of their autonomy. Thus, intervention programs aiming at promoting the healthy development of victimized left-behind adolescents should not be restricted to the school environment but should also target their mothers. For example, school counselors, community members, social workers, and other professionals could meet the victim’s mothers and examine their levels of psychological control and behavioral control, and thus give appropriate suggestions to help left-behind mothers optimize their parenting behaviors based on different situations. Finally, the limited protective role of maternal behavioral control also enlightens us to consider other relevant important factors such as teacher support for the positive development of left-behind adolescents.

Ethics approval and informed consent

All procedures performed in the present study were in accordance with the recommendations of the Research Ethics Committee of the Beijing Normal University and with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from both left-behind adolescents and their caregivers included in the study.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant Number: 31900772].

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. All-China Women’s Federation. China’s rural left-behind children, rural and urban migrant children research report. Chin Women’s Mov. 2013;20(6):30–34.

2. Wu ZH, Li MJ. The investigation report of survival status for left-behind children in rural areas. China Agric Univ J Social Sci Ed. 2015;32(1):65–74.

3. Zhao JX, Zhao JX, Wang MF. The transmission of anxiety from left-behind women to children: moderated mediating effect. Psycho Dev Edu. 2018;34(6):724–731.

4. Hawker DS, Boulton MJ. Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: a meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41(4):441–455.

5. Van Geel M, Goemans A, Vedder P. A meta-analysis on the relation between peer victimization and adolescent non-suicidal self-injury. Psychiatry Res. 2015;230(2):364–368. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2015.09.017

6. Klomek AB, Marrocco F, Kleinman M, Schonfeld IS, Gould MS. Peer victimization, depression, and suicidiality in adolescents. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2008;38(2):166–180.

7. Zimmer-Gembeck M, Trevaskis J, Nesdale S, Downey D. Relational victimization, loneliness and depressive symptoms: indirect associations via self and peer reports of rejection sensitivity. J Youth Adolesc. 2014;43(4):568–582. doi:10.1007/s10964-013-9993-6

8. McDougall P, Vaillancourt T. Long-term adult outcomes of peer victimization in childhood and adolescence: pathways to adjustment and maladjustment. Amer Psychol. 2015;70(4):300–310. doi:10.1037/a0039174

9. Wolke D, Copeland WE, Angold A, Costello EJ. Impact of bullying in childhood on adult health, wealth, crime, and social outcomes. Psychol Sci. 2013;24(10):1958–1970. doi:10.1177/0956797613481608

10. Chen M, Chan KL. Parental absence, child victimization, and psychological well-being in rural China. Child Abuse Negl. 2016;59:45–54.

11. Chen X, Liang N, Ostertag SF. Victimization of children left behind in rural China. J Res Crime Delinq. 2017;54(4):515–543.

12. Tang W, Wang G, Hu T, et al. Mental health and psychosocial problems among Chinese left-behind children: a cross-sectional comparative study. J Affect Disord. 2018;241:133–141. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2018.08.017

13. Bean RA, Barber BK, Crane DR. Parental support, behavioral control, and psychological control among African American youth. J Fam Issues. 2006;27(10):1335–1355.

14. Barber BK. Parental psychological control: revisiting a neglected construct. Child Dev. 1996;67(6):3296–3319.

15. Mandara J, Pikes CL. Guilt trips and love withdrawal: does mothers’ use of psychological control predict depressive symptoms among African American adolescents? Fam Relat. 2008;57(5):602–612.

16. Soenens B, Park S, Vansteenkiste M, Mouratidis A. Perceived parental psychological control and adolescent depressive experiences: a cross-cultural study with Belgian and South-Korean adolescents. J Adolesc. 2012;35(2):261–272. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.05.001

17. Koçak A, Mouratidis A, Sayıl M, Kındap-Tepe Y, Uçanok Z. Interparental conflict and adolescents’ relational aggression and loneliness: the mediating role of maternal psychological control. J Child Fam Stud. 2017;26(12):3546–3558.

18. Pinquart M. Associations of parenting dimensions and styles with externalizing problems of children and adolescents: an updated meta-analysis. Dev Psychol. 2017;53(5):873–932. doi:10.1037/dev0000295

19. Scharf M, Goldner L. “If you really love me, you will do/be … ”: parental psychological control and its implications for children’s adjustment. Dev Rev. 2018;49:16–30.

20. Soenens B, Vansteenkiste M. A theoretical upgrade of the concept of parental psychological control: proposing new insights on the basis of self-determination theory. Dev Rev. 2010;30(1):74–99.

21. Akcinar B, Baydar N. Parental control is not unconditionally detrimental for externalizing behaviors in early childhood. Int J Behav Dev. 2014;38(2):118–127.

22. Harris-McKoy D, Cui M. Parental control, adolescent delinquency, and young adult criminal behavior. J Child Fam Stud. 2013;22(6):836–843.

23. Racz SJ, McMahon RJ. The relationship between parental knowledge and monitoring and child and adolescent conduct problems: a 10-Year Update. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2011;14(4):377–398. doi:10.1007/s10567-011-0099-y

24. Willoughby T, Hamza CA. A longitudinal examination of the bidirectional associations among perceived parenting behaviors, adolescent disclosure and problem behavior across the high school years. J Youth Adolesc. 2011;40(4):463–478. doi:10.1007/s10964-010-9567-9

25. Wang Q, Pomerantz EM, Chen H. The role of parents’ control in early adolescents’ psychological functioning: a longitudinal investigation in the US and China. Child Dev. 2007;78:1592–1610. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01085.x

26. Jacobson K, Crockett L. Parental monitoring and adolescent adjustment: an ecological perspective. J Res Adolescence. 2000;10(1):65–97.

27. Noom M, Deković J, Meeus M. Conceptual analysis and measurement of adolescent autonomy. J Youth Adolesc. 2001;30(5):577–595.

28. Rekker R, Keijsers L, Branje S, Koot H, Meeus W. The interplay of parental monitoring and socioeconomic status in predicting minor delinquency between and within adolescents. J Adolesc. 2017;59:155–165. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.06.001

29. Kerr M, Stattin H, Burk WJ. A reinterpretation of parental monitoring in longitudinal perspective. J Res Adolescence. 2010;20(1):38–64.

30. Kiesner J, Dishion TJ, Poulin F, Pastore M. Temporal dynamics linking aspects of parent monitoring with early adolescent antisocial behavior. Social Dev. 2009;18(4):765–784. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00525.x

31. Laird RD, Marrero MD, Sentse M. Revisiting parental monitoring: evidence that parental solicitation can be effective when needed most. J Youth Adolesc. 2010;39(12):1431–1441. doi:10.1007/s10964-009-9453-5

32. Hawk ST, Hale WW, Raaijmakers QA, Meeus W. Adolescents’ perceptions of privacy invasion in reaction to parental solicitation and control. J Early Adolescence. 2008;28(4):583–608.

33. Keijsers L, Frijns T, Branje SJT, Meeus W. Developmental links of adolescent disclosure, parental solicitation, and control with delinquency: moderation by parental support. Dev Psychol. 2009;45(5):1314–1327. doi:10.1037/a0016693

34. Aunola K, Nurmi JE. The role of parenting styles in children’s problem behavior. Child Dev. 2005;76(6):1144–1159. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00841.x

35. Galambos NL, Barker ET, Almeida DM. Parents do matter: trajectories of change in externalizing and internalizing problems in early adolescence. Child Dev. 2003;74(2):578–594.

36. Stattin H, Kerr M. Parental monitoring: a reinterpretation. Child Dev. 2000;71:1072–1085.

37. Roche KM, Leventhal T. Beyond neighborhood poverty: family management, neighborhood disorder, and adolescents’ early sexual onset. J Fam Psychol. 2009;23(6):819–827. doi:10.1037/a0016554

38. Jiang Y, Yu C, Zhang W, Bao Z, Zhu J. Peer victimization and substance use in early adolescence: influences of deviant peer affiliation and parental knowledge. J Child Fam Stud. 2016;25(7):2130–2140.

39. Mynard H, Joseph S. Development of the multidimensional peer-victimization scale. Aggress Behav. 2000;26(2):169–178.

40. Guo HY, Chen LH, Ye Z, Pan J, Lin DH. Characteristics of peer victimization and the bidirectional relationship between peer victimization and internalizing problems among rural-to-urban migrant children in China: a longitudinal study. Acta Psychologica Sin. 2017;49(3):336–348.

41. Cheung SS, Pomerantz EM. Parents’ involvement in children’s learning in the United States and China: implications for children’s academic and emotional adjustment. Child Dev. 2011;82(3):932–950. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01582.x

42. Barber B, Stolz H, Olsen J. Parental support, psychological control, and behavioral control: assessing relevance across time, culture, and method. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 2005;70(4):1–137. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5834.2005.00365.x

43. Zhao JX. Parental monitoring and left-behind children’s antisocial behavior and loneliness. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2013;21(3):500–504.

44. Gratz KL. Measurement of deliberate self-harm: preliminary data on the deliberate self-harm inventory. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2001;23(4):253–263. doi:10.1023/A:1012779403943

45. Lundh LG, Karim J, Quilisch E. Deliberate self-harm in 15-year-old adolescents: a pilot study with a modified version of the deliberate self-harm inventory. Scand J Psychol. 2007;48(1):33–41. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9450.2007.00567.x

46. Fendrich M, Weissman M, Warner V. Screening for depressive disorder in children and adolescents: validating the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale for children. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;131(3):538. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115529

47. Chen ZY, Yang XD, Li XY. Psychometric features of CES-D in Chinese adolescents. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2009;17(4):443–445.

48. Asher SR, Hymel S, Renshaw PD. Loneliness in children. Child Dev. 1984;55(4):1456–1464.

49. Li XW, Zhou H, Liu Y. Psychometric evaluation of loneliness scale in Chinese middle school students. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2014;22(4):731–733.

50. Hart CH, Newell LD, Olsen SF. Parenting skills and social-communicative competence in childhood. In: Greene JO, Burleson BR, editors. Handbook of Communication and Social Interaction Skills. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003:753–797.

51. Ma TL, Bellmore A. Peer victimization and parental psychological control in adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2012;40(3):413–424. doi:10.1007/s10802-011-9576-5

52. Kakihara F, Tilton-Weaver L. Adolescents’ interpretations of parental control: differentiated by domain and types of control. Child Dev. 2009;80(6):1722–1738. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01364.x

53. Casper D, Card N. Overt and relational victimization: a meta‐analytic review of their overlap and associations with social-psychological adjustment. Child Dev. 2017;88(2):466–483. doi:10.1111/cdev.12621

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.