Back to Journals » Journal of Pain Research » Volume 14

Patient, Provider Type, and Procedure Type Factors Associated with Opioid Prescribing by Dentists in a Health Care System

Authors Rindal DB , Asche SE , Kane S , Truitt AR , Worley DC, Davin LM, Gryczynski J, Mitchell SG

Received 22 July 2021

Accepted for publication 30 September 2021

Published 20 October 2021 Volume 2021:14 Pages 3309—3319

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S330598

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr David Keith

D Brad Rindal,1 Stephen E Asche,1 Sheryl Kane,1 Anjali R Truitt,1 Donald C Worley,1 Lauryn M Davin,1 Jan Gryczynski,2 Shannon G Mitchell2

1HealthPartners Institute, Minneapolis, MN, USA; 2Friends Research Institute, Baltimore, MD, USA

Correspondence: D Brad Rindal

HealthPartners Institute, 8170 33rd Ave. So. MS21112R, Minneapolis, MN, 55444, USA

Tel +1 952-967-5026

Email [email protected]

Introduction: Reports examining opioid prescribing for dental conditions are limited and do not examine patient-level factors. This study examines the association of patient age, sex, race, ethnicity, Medicaid coverage, and the need for an interpreter in addition to procedure type and dental provider type with receipt of an opioid prescription in dental care settings within a large health system.

Materials and Methods: This study was conducted utilizing data from the electronic health record of HealthPartners, a large dental practice embedded within a health care system. The analytic sample consisted of all 169,173 encounters from 90,487 patients undergoing a dental procedure in the baseline period (9/1/2018 to 8/30/2019), prior to implementing a clinical trial to de-implement opioids in dentistry.

Results: Opioids were prescribed at 1.9% of all 169,173 encounters and rates varied by patient factors, procedure category, and provider type. Opioid prescriptions were most likely for extraction encounters (25.9%). In a multivariable analysis of 8760 extraction encounters, all patient age groups were more likely than those age 66+ to receive an opioid prescription, particularly those age 18– 25 (OR=6.94). Patients having a complex rather than simple extraction were more likely to receive an opioid prescription (OR=6.31) and those seen by an oral surgeon rather than a general dentist (OR=9.11) were more likely to receive an opioid prescription. Among 108,748 encounters with a diagnostic procedure, opioid prescribing was more likely among male than female patients (OR=1.20), Black patients relative to White (OR=1.69), patients with Medicaid coverage (OR=1.86), and patients seeing an oral surgeon rather than a general dentist (OR=27.81).

Conclusion: Opioid prescribing rates vary considerably depending on procedure type. Patterns of associations between patient factors and opioid prescribing also vary considerably across procedure type. To understand which patient groups are more at risk of being prescribed opioids, it is essential to consider the procedures they are receiving.

Keywords: dentistry, oral surgical procedures, analgesics, opioid, prescribing, practice patterns

Background

The United States is in the midst of an epidemic of prescription drug overdose deaths, with deaths associated with prescription pain relievers of particular concern.1 Drug overdose has become a leading cause of accidental death in the United States.2,3 Opioids are currently the most commonly prescribed class of medications in the United States.4 Between 2000 and 2015, the rate of deaths from drug overdoses increased 137%, including a 200% increase in the rate of overdose-related deaths involving opioids (opioid pain relievers and heroin).5 Inappropriate opioid prescribing, heroin use, and increased illicitly manufactured fentanyl use have contributed to this opioid epidemic,6 and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has strongly recommended fundamental changes in prescribing practices to address this public health emergency.7

Opioids have been among the most frequently prescribed drugs by dentists.8 In 2009, dentists wrote for 8.0% (6.4 million prescriptions) of the opioid prescriptions in the United States, and for patients aged 10 to 19 years, dentists were the main prescribers (30.8%, 0.7 million prescriptions).9 While the overall rate of dentist-prescribed opioids has decreased across all age groups,10 from 2010 to 2015, the number of dentist-prescribed opioids for 11–18 year olds increased.11 Estimated 5 million people undergo third-molar extractions in the United States annually.12 Many patients younger than 25 years are introduced to prescription opioids for the first time after having third-molar surgeries.13 Use of these prescriptions for this age group appears to be associated with an increased risk of subsequent opioid use and abuse.14 Opioid prescribing by dental professionals increased from 1996 to 2013 after adjusting for personal characteristics and type of dental procedure.15 There is a need to recognize the contribution of dental prescriptions to the opioid epidemic when opioids are prescribed to at-risk patients.16

Friedman et al examined differential exposure to opioids via health care systems to investigate racial differences in the patterning of the opioid epidemic. They found that overdoses tend to mirror prescription rates generated by the health care systems.17 Differences also exist by provider type. A study examining North Carolina Medicaid claims data found that race-based differences in beneficiaries’ dispensed opioid prescriptions for chronic non-cancer pain were more prominent in certain specialties.18 A study examining opioid prescribing during emergency department visits found that Blacks were less likely to receive an opioid prescription for back pain and abdominal pain, but not for toothache compared to Whites.19

Research investigating the prescribing patterns of dentists is sparse.20 The NIH HEAL Initiative is funding research to develop better pain treatments that reduce reliance on opioids for various pain conditions and procedures.21 Most of the publications utilize claims and administrative data that do not include patient characteristics, which would help us better understand who might be impacted and who is at greater risk for developing an opioid use disorder. The primary objective of this study was to identify specific factors (patient age, sex, race, ethnicity, Medicaid coverage, need for an interpreter, procedure type and dental provider type) associated with patient receipt of an opioid prescription in dental care settings within a large health system.

Methods

The current study was supported by a Helping to End Addiction Long-Term (HEAL) Initiative22 supplement to the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) supporting clinical trial testing approaches to de-implement opioids related to dental extractions. The present study draws upon clinical data from services delivered prior to launching the parent trial’s intervention.

Description of Parent Trial

The parent study is a prospective, 3-arm, cluster randomized trial in which dentists were randomized in a 1:1:1 allocation ratio to either standard practice (SP), clinical decision support or clinical decision support plus patient education. Opioid prescribing measured at the encounter-level served as the primary outcome. A complete description of the study protocol has been published elsewhere.23

Setting and Data

The study is being conducted at HealthPartners, the largest consumer-governed nonprofit health care organization in the US. HealthPartners mission is centered on providing care, coverage, research, and education to improve health and well-being in partnership with its members, patients and community. The organization includes a multispecialty medical and dental group practice that included 75 dentists and 24 dental clinics in Minnesota at the time when this dataset was pulled. For the past 18 years, the medical and dental clinics have fully implemented electronic health records (EHRs) with integrated diagnosis codes. The HealthPartners Institute utilizes these systems to conduct research. All data for the present study were extracted from the HealthPartners EHR.

Analytic Sample

The analytic sample consisted of all 169,173 encounters from 90,487 patients undergoing a dental procedure in the baseline period (9/1/2018 to 8/30/2019), prior to implementing the clinical trial interventions (Figure 1). This includes data from 22 HealthPartners dental clinics and 65 dental providers. This total excludes encounters having orthodontic procedure codes [D8000-D8999] and encounters exclusively having an adjunctive non-palliative procedure code. These procedure codes were excluded because pain is not an anticipated sequela of these procedures.

|

Figure 1 Analytic sample and distribution of patient encounter in procedure categories. |

The study summarized the likelihood of an opioid prescription within 7 days of the encounter by patient, provider type, and procedure-type factors. The 7-day window was chosen because pain is most significant in the week following the procedure. Analgesic prescribing occurs the day of the procedure, but the patient could contact the provider if the pain management is not adequate resulting in an additional prescription. Opioid prescribing was computed for all encounters, and within encounters based on specific procedure code categories (diagnostic [D0100-D0999], preventive [D1000-D1999], restorative [D2000-D2999], endodontic [D3000-D3999], periodontal [D4000-D4999], prosthetic removable [D5000-D5999], prosthetic fixed [D6000-D6999], oral surgery non-extraction [D7000-D7999], extraction [D7111, D7140, D7210, D7220, D7230, D7240, D7241, D7250], and adjunctive palliative procedures [D9000-D9999]).

To examine variation in opioid prescribing by patient attributes and provider type, the percentage of encounters with an opioid prescription was summarized descriptively in terms of counts and percentages across patient characteristics, including age group, sex, race (White, Black, Asian, other [including multiracial, American Indian/Alaskan Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander], unknown), Hispanic ethnicity, insurance (Medicaid vs other payment), need for an interpreter, and extraction complexity (complex, simple). Likewise, encounter-level opioid prescribing was examined by provider type (general dentist, endodontist, oral surgeon, pediatric dentist, periodontist, or prosthodontist). These analyses were then repeated within encounters having an extraction procedure in order to summarize opioid prescribing for simple vs complex extractions, and within encounters that have prosthetic fixed procedures in order to summarize opioid prescribing for implant procedures vs non-implant procedures.

Adjusted associations of opioid prescribing within 7 days of encounter, with patient factors and provider type, were examined in logistic regression analysis predicting opioid prescribing. Independent variables included patient age group, patient gender, patient race, Hispanic ethnicity, need for an interpreter, Medicaid vs other payment, extraction complexity (for the analysis of extraction procedures only), and provider type (general dentist, oral surgeon, other specialist). A generalized estimating equations (GEE) approach with an exchangeable correlation structure for repeated responses was used to account for multiple encounters from the same patient. These analyses were conducted separately for encounters with diagnostic procedures and extraction procedures. This analysis was not conducted within other procedure categories due to the small number of opioid prescribing events relative to degrees of freedom in the model, and was not conducted for the pooled sample of all procedure categories due to substantial variation across procedure types in opioid prescribing levels. Analyses were conducted with SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary NC). Statistical tests and confidence intervals used alpha=0.05.

Results

The 169,173 encounters in the analytic sample consisted of 139,304 (82%) with procedures in a single category, and 29,869 (28%) with procedures in two or more categories (Figure 1). Encounters with diagnostic or restorative procedures made up 94% of all single-procedure category encounters.

Patient Characteristics

Over half (57%) of patients were female, 22% were under age 18, 32% were age 18–45, and 46% were over age 45 (Table 1). Non-white patients made up 25% of the sample, and 5% were of Hispanic ethnicity. One-third (33%) of patients had Medicaid coverage and 5% needed an interpreter at the encounter. A review of high-level patterns (frequencies and percentages) in patient attributes across procedure categories suggests the age group distribution of patients varied by the type of procedure conducted at the encounter. Patients with preventive procedures were younger than the overall sample, while patients with endodontic, periodontal, prosthetic removable, prosthetic fixed, and adjunctive palliative procedures were older. The racial and ethnic composition of patients across procedure types were similar except for patients with preventive procedures – of whom 37% were white and 10% Hispanic, and prosthetic fixed procedures – of whom 80% were white and 2% Hispanic. Patients with preventive, prosthetic removable, extraction and adjunctive palliative procedures were more likely than the overall sample to have Medicaid coverage, while patients with periodontal and prosthetic fixed procedures were less likely to have Medicaid coverage. The need for an interpreter was highest among patients with prosthetic removable procedures and lowest for patients with prosthetic fixed procedures.

|

Table 1 Patient Attributes and Provider Type, Overall and Within Procedure Type for Dental Encounters from 9/1/18 to 8/30/19 with a Billed Procedure |

Provider Characteristics

Among the 65 providers linked to encounters, 49% were women, median age was 42, and there were 50 general dentists, 4 oral surgeons, 4 pediatric dentists, 3 prosthodontists, 2 endodontists and 2 periodontists. General dentists provided care at 88% of encounters in the overall sample. Care at the remaining 12% of encounters was linked to five specialist provider types. Provider types varied considerably by the type of procedures conducted at the encounter. General dentists provided care at more than 87% of encounters for diagnostic, restorative, and prosthetic removable procedures. Compared to care in the overall sample, oral surgeons provided care more often at prosthetic fixed (26%), oral surgery non-extraction (58%), and extraction procedures (32%). Predictably, pediatric dentists provided most of the care (52%) at encounters with preventive procedures, endodontists provided care at 44% of encounters with endodontic procedures, periodontists provided care at 95% of periodontal procedures, and prosthodontists were more likely to be involved in encounters with prosthetic removable (12%) and fixed procedures (17%) than in the overall sample (1%). Provider types involved in simple vs complex extractions and involved in implant vs non-implant prosthetic fixed procedures are presented in Supplemental Table 1.

Opioid Prescribing Patterns

Overall, 3229 encounters (1.9%) received an opioid prescription within 7 days, with rates varying considerably by procedure type (Table 2). Opioid prescribing at encounters with a diagnostic and/or extraction procedure accounted for 94% of all encounters at which an opioid was prescribed. The percentage of encounters with an opioid prescribed was highest in encounters involving extraction procedures (26.0%), oral surgery non-extraction (25.1%), and prosthetic fixed (9.2%) procedures, and the lowest in preventive (0.03%), restorative (0.3%), prosthetic removable (0.6%) and diagnostic (0.8%) encounters.

|

Table 2 Percentage of Encounters with an Opioid Prescription Within 7 Days of the Index Encounter, by Procedure Type, Patient Attributes, and Provider Type |

Among all encounters, opioid prescribing did not vary by patient gender, but varied by other patient factors and was directionally highest among patients aged 18–25 (6.8%) compared to younger and older age groups. Opioid prescribing was directionally more likely for patients who were non-white (Black, Asian, Other, Unknown) (2.2% vs 1.7% for White), Hispanic (2.5% vs 1.9% for non-Hispanic), with Medicaid coverage (2.7% vs 1.5% for patients without Medicaid coverage), and who did not need an interpreter (1.9% vs 1.5 for patients who needed an interpreter). Many of these directional patterns in the pooled sample were not consistent across encounters having different procedure codes. For instance, among encounters with an oral surgery non-extraction procedure, 30.9% of male patients received an opioid prescription compared with 21.1% of female patients.

Opioids were prescribed at 40.1% of encounters involving oral surgeons. Other providers prescribed opioid analgesics at less than 1% of all encounters. Opioids were prescribed by general dentists at 9.9% of encounters with an oral surgery non-extraction procedure, and 7.9% of encounters with an extraction procedure. Opioids were prescribed by periodontists at 16.7% of encounters with an implant (see Supplemental Table 2). Supplemental Table 2 illustrates opioid prescribing for complex vs simple extractions overall and across patient subgroups. All opioid prescribing for encounters with prosthetic fixed procedures involved implants.

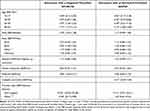

Multivariable Analysis Examining Associations with Opioid Prescribing

In the adjusted analysis of encounters with a diagnostic procedure (Table 3), patients in age groups 26–45 (OR=1.87) and 46–65 (OR=1.71) were more likely than patients age 66 and higher to receive an opioid prescription, while patients age 12–17 were less likely (OR=0.20) to receive an opioid prescription. Patients under age 12 were removed from the analysis due to convergence problems caused by rare opioid prescribing (n=7 encounters with an opioid prescription) in this group. Opioid prescribing was more likely among male than female patients (OR=1.20), Black patients relative to White (OR=1.69), and patients with Medicaid coverage (OR=1.86). Compared to patients seeing general dentists, patients with encounters linked to other providers types (endodontist, pediatric dentist, periodontist, prosthodontist) were less likely to receive an opioid prescription (OR=0.40), while patients with encounters linked to oral surgeons were more likely to receive an opioid prescription (OR=27.81). In the adjusted analysis of encounters with an extraction procedure, all patient age groups were more likely than those age 66+ to receive an opioid prescription, particularly those age 18–25 (OR=6.94). Patients having a complex rather than simple extraction were more likely to receive an opioid prescription (OR=6.31) and those seen by an oral surgeon rather than a general dentist (OR=9.11) were more likely to receive an opioid prescription.

|

Table 3 Adjusted Associations of Opioid Prescribing Within 7 Days of the Index Encounter with Patient Attributes and Provider Type, Within Encounters Having Diagnostic and Extraction Procedures |

Discussion

Key Results

This study examined patterns of opioid prescribing for dental procedures in a large health system, characterizing differences based on patient factors, provider type, and procedure type.

The patient sample for this analysis was diverse, with 25% being non-white and 33% being of lower socioeconomic status as defined by qualifying for Medicaid coverage. Opioids were prescribed at 1.9% of encounters, yet prescribing rates varied considerably by procedure type and by patient factors across procedure type. To understand which patient groups are more at risk of being prescribed opioids, it is essential to take into account the particular procedures they are receiving.

In diagnostic and extraction encounters, patient age group and provider type were associated with receiving an opioid prescription, with opioid prescriptions more likely among encounters with oral surgeons than general dentists. The pattern of association with age groups was not consistent across diagnostic and extraction encounters. Among diagnostic encounters, opioid prescribing was more likely among male, Black, and Medicaid-covered patients. These patient-level factors were not significantly associated with opioid prescribing in extraction encounters.

Among extraction encounters, compared to patients over age 65, patients in the 12–17 age group were 4 times more likely to receive an opioid, while patients in the 18–25 age group were nearly 7 times more likely to receive an opioid. The most common procedure for this age group is the removal of third molars. This pattern is concerning because this age group is at greater risk of developing an opioid use disorder.24,25

Individuals covered by Medicaid made up a small percentage of encounters receiving fixed prosthetic and periodontal procedures (Table 1). Benefits of these services are limited under Medicaid, while extractions and removable prosthetics are more often covered by these programs.

Comparing Our Results to Other Data

Previous research examining Medicaid claims data found that Whites and Blacks were approximately twice as likely to receive opioids as were Hispanics. Our data showed that Blacks but not Whites were more likely to receive an opioid prescription among extraction, but not diagnostic, encounters. Despite Hispanics being directionally more likely to receive an opioid in descriptive analyses, there were no significant differences in opioid prescribing on the basis of Hispanic ethnicity in either diagnostic or extraction procedure types. In addition, prior research has shown that patients receiving oral health care in an emergency department were more than 7 times more likely to receive an opioid prescription than were patients treated in a dental office.26 Although that population is different from ours, their results align with ours showing that African Americans were more likely to receive an opioid. In contrast to this study, which found that females were more likely to receive an opioid, our results showed that opioid prescriptions were more common in male patients for encounters with diagnostic procedures. They were also only able to examine dental diagnoses, but not dental procedures, creating a limitation in comparing our results in this study.

A robust, evidence-based guideline for managing pain after dental procedures does not currently exist. The American Dental Association guidance states that “Dentists should consider nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory analgesics as the first-line therapy for acute pain management and should recognize multimodal pain strategies for management for acute postoperative pain as a means for sparing the need for opioid analgesics.”27 The CDC also provides guidance that applies broadly to clinicians: “Clinicians should prescribe the lowest effective dose of immediate-release opioids and should prescribe no greater quantity than needed for the expected duration of pain severe enough to require opioids. Three days or less will often be sufficient; more than seven days will rarely be needed.”28

Limitations

This study has a number of limitations. Although a strength of the study is the large sample of dental encounters in a health system spanning multiple sites and providers, we were limited by the information available in the EHR, which may not capture all relevant explanatory variables or capture them completely. These include other potential explanatory patient factors, such as disease severity, and pain level prior to the procedure and limited knowledge of the risks with opioids. Hispanic ethnicity was missing for 30% of encounters and race information was missing for 15% of encounters. Additional provider factors of interest include prescribing behavior, perceived benefits and harm from an opioid, the types of procedures performed and insurance coverage. In addition, another potential limitation is that we analyzed encounters rather than patients, although the non-independence from repeat encounters with the same patient was accounted for in the multivariable adjusted analysis. In addition, multiple procedure categories within an encounter would result in an opioid being associated with more than one procedure, leading to less precision in determining which procedure types may be driving opioid prescriptions.

The number of providers in each specialty was small, increasing the risk that the reported prescribing practices were influenced by individual variation rather than specialty association. While segregation of procedure categories gives some insight into the indications for opioid prescriptions, the extent to which prescribing practices were determined by procedures performed at the encounter versus the type of provider could not be determined by this study.

Future Directions

These results suggest further opportunities to reduce opioid prescribing related to oral surgery procedures. Given the known risks associated with opioid prescribing in younger patients29 and the evidence supporting the use of non-opioid postoperative pain management for third molar extractions,30,31 further efforts to reduce the reliance on opioids for post-extraction pain are warranted. A growing body of evidence shows that opioids are not needed for routine oral health care.32

Conclusions

Considering the large number of dental encounters that occurred in this time period, opioids were infrequently (1.9%) prescribed. However, opioid prescribing rates were still high (9–26%) for more invasive procedures (prosthetic fixed, oral surgery non-extraction procedures, extractions). Evidence supports the use of non-opioid combinations as they have similar efficacy to opioid combinations. In addition, younger individuals are at greater risk of developing an opioid use disorder if introduced to an opioid by age 25. Current opioid prescribing by dentists is low, but the profession still has opportunities to further reduce opioid prescribing.

Abbreviations

NIDCR, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; HEAL, Helping to End Addiction Long-Term (HEAL) Initiative; HER, electronic health records; SP, standard practice; GEE, generalized estimating equations.

Informed Consent/IRB Statement

This study (18-186) was reviewed and approved by the HealthPartners Institute Institutional Review Board. Patients who requested not to have their data used in research studies were excluded from the study. The trial was conducted in accordance with the International Council on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice, the United States Code of Federal Regulations applicable to clinical studies, and the funder’s Terms and Conditions of Award, and the data accessed complied with relevant data protection and privacy regulations.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Julie Session for her assistance in manuscript preparation.

Author Contributions

All authors (1) made a significant contribution to the work reported, (2) have drafted or written, or substantially revised or critically reviewed the article, (3) have agreed on the journal to which the article will be submitted, (4) reviewed and agreed on all versions of the article before submission and (5) Agree to take responsibility and be accountable for the contents of the article.

Funding

The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Dental & Craniofacial Research and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U01DE027441. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure

Unrelated to the present study, Dr. Gryczynski has received research funding from Indivior (paid to his institution and including project-related salary support) and is part of the owner of COG Analytics; and grants from NIH/NIDA, outside the submitted work. Mr Stephen E Asche reports grants from NIDCR, during the conduct of the study. No other authors have any competing interests.

References

1. United States Government Accountability Office (GAO). Prescription Pain Reliever Abuse; 2011.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Unintentional Drug Poisoning in the United States; 2010.

3. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Opioid overdose what can you do to prevent opioid overdose deaths?; 2020. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/index.html.

4. Volkow ND, McLellan AT. Opioid abuse in chronic pain–misconceptions and mitigation strategies. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(13):1253–1263. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1507771

5. Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2010–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(5051):1445–1452. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm655051e1

6. Rummans TA, Burton MC, Dawson NL. How good intentions contributed to bad outcomes: the opioid crisis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93(3):344–350. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.12.020

7. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), Behavioral Health Coordinating Committee, Prescription Drug Abuse Subcommittee. Addressing Prescription Drug Abuse in the United States Current Activities and Future Opportunities. Washington, DC; 2014.

8. Moore PA, Nahouraii HS, Zovko JG, Wisniewski SR. Dental therapeutic practice patterns in the U.S. II. Analgesics, corticosteroids, and antibiotics. Gen Dent. 2006;54(3):

9. Volkow ND, McLellan TA, Cotto JH, Karithanom M, Weiss SR. Characteristics of opioid prescriptions in 2009. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1299–1301. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.401

10. Levy B, Paulozzi L, Mack KA, Jones CM. Trends in opioid analgesic-prescribing rates by specialty, U.S., 2007–2012. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(3):409–413. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.02.020

11. Gupta N, Vujicic M, Blatz A. Multiple opioid prescriptions among privately insured dental patients in the United States: evidence from claims data. J Am Dent Assoc. 2018;149(7):619–627.e611. doi:10.1016/j.adaj.2018.02.025

12. Friedman JW. The prophylactic extraction of third molars: a public health hazard. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(9):1554–1559. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2006.100271

13. Pogrel MA, Dodson TB, Swift JQ, et al. White paper on third molar data. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons; 2007:1–25.

14. Schroeder AR, Dehghan M, Newman TB, Bentley JP, Park KT. Association of opioid prescriptions from dental clinicians for US adolescents and young adults with subsequent opioid use and abuse. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(2):145–152. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5419

15. Steinmetz CN, Zheng C, Okunseri E, Szabo A, Okunseri C. Opioid analgesic prescribing practices of dental professionals in the United States. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2017;2(3):241–248.

16. Sabounchi SS, Sabounchi SS, Cosler LE, Atav AS. Opioid prescribing and misuse among dental patients in the US: a literature-based review. Quintessence Int. 2020;51(1):64–76.

17. Friedman J, Kim D, Schneberk T, et al. Assessment of racial/ethnic and income disparities in the prescription of opioids and other controlled medications in California. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(4):469–476. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6721

18. Ringwalt C, Roberts AW, Gugelmann H, Skinner AC. Racial disparities across provider specialties in opioid prescriptions dispensed to Medicaid beneficiaries with chronic noncancer pain. Pain Med. 2015;16(4):633–640. doi:10.1111/pme.12555

19. Singhal A, Tien YY, Hsia RY. Racial-ethnic disparities in opioid prescriptions at emergency department visits for conditions commonly associated with prescription drug abuse. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0159224. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0159224

20. Lutfiyya MN, Gross AJ, Schvaneveldt N, Woo A, Lipsky MS. A scoping review exploring the opioid prescribing practices of US dental professionals. J Am Dent Assoc. 2018;149(12):1011–1023. doi:10.1016/j.adaj.2018.07.017

21. Nadeau R, Hasstedt K, Sunstrum AB, Wagner C, Tu H. Addressing the opioid epidemic: impact of opioid prescribing protocol at the University of Minnesota School of Dentistry. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2018;11(2):104–110. doi:10.1055/s-0038-1649498

22. Helping to End Addiction Long-Term (HEAL) Initiative. NCT03584789: National Institute of Dental & Craniofacial Research (NIDCR). Available from: https://heal.nih.gov/.

23. Rindal DB, Asche SE, Gryczynski J, et al. De-Implementing Opioid Use and Implementing Optimal Pain Management Following Dental Extractions (DIODE): protocol for a cluster randomized trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2021;10(4):e24342. doi:10.2196/24342

24. Webster LR. Risk factors for opioid-use disorder and overdose. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(5):1741–1748. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000002496

25. Naji L, Dennis BB, Bawor M, et al. The association between age of onset of opioid use and comorbidity among opioid dependent patients receiving methadone maintenance therapy. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2017;12(1):9. doi:10.1186/s13722-017-0074-0

26. Janakiram C, Chalmers NI, Fontelo P, et al. Sex and race or ethnicity disparities in opioid prescriptions for dental diagnoses among patients receiving Medicaid. J Am Dent Assoc. 2019;150(10):e135–e144. doi:10.1016/j.adaj.2019.06.016

27. American Dental Association (ADA). Frequently asked questions for opioid prescribing; 2018. Available from: https://www.ada.org/en/advocacy/advocacy-issues/opioid-crisis/faqs-on-opioid-prescribing.

28. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Postsurgical Pain; 2020. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/acute-pain/postsurgical-pain/index.html.

29. Miech R, Johnston L, O’Malley PM, Keyes KM, Heard K. Prescription opioids in adolescence and future opioid misuse. Pediatrics. 2015;136(5):e1169–1177. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-1364

30. Moore RA, Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Maguire T, Roy YM, Tyrrell L. Non-prescription (OTC) oral analgesics for acute pain - an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(11):CD010794. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010794.pub2

31. Moore PA, Ziegler KM, Lipman RD, Aminoshariae A, Carrasco-Labra A, Mariotti A. Benefits and harms associated with analgesic medications used in the management of acute dental pain: an overview of systematic reviews. J Am Dent Assoc. 2018;149(4):256–265. doi:10.1016/j.adaj.2018.02.012

32. Thornhill MH, Suda KJ, Durkin MJ, Lockhart PB. Is it time US dentistry ended its opioid dependence? J Am Dent Assoc. 2019;150(10):883–889. doi:10.1016/j.adaj.2019.07.003

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.