Back to Journals » Clinical Ophthalmology » Volume 15

Patient Experience Survey in a Corneal Service Conducted by Remote Consultation

Authors Hakim N , Longmore P , Hu VH

Received 15 August 2021

Accepted for publication 7 September 2021

Published 19 December 2021 Volume 2021:15 Pages 4747—4754

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S331622

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Navid Hakim,1 Philippa Longmore,1 Victor H Hu1,2

1Eye Department, Mid Cheshire NHS Hospitals Foundation Trust, Crewe, UK; 2International Centre for Eye Health, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK

Correspondence: Navid Hakim

Eye Department, Mid Cheshire NHS Hospitals Foundation Trust, Crewe, CW1 4QJ, UK

Tel +44 7540492816

Email [email protected]

Introduction: An ophthalmic remote consultation clinic was implemented due to the COVID-19 pandemic for stable patients under the corneal service in a district general hospital in Cheshire, UK. Patients were reviewed either by video or telephone consultation. The purpose of this survey was to assess patient satisfaction with this service.

Methods: Consecutive patients who were seen by remote consultation between September 2020 and November 2020 were identified. Approval for the survey was gained from the hospital Patient Experience and Survey department. A telephone survey was conducted between 4 and 8 weeks after the initial patient appointment. Data were obtained for patient demographic information, appointment details and patient satisfaction with their appointment, including preference for subsequent appointments and open feedback.

Results: Eighty-four remote consultations were identified and 51 (60.7%) patients completed the survey: 48 (94.1%) reported satisfaction with their remote consultation; 36 (70.5%) reported satisfaction for a subsequent remote consultation; and 33 (64.7%) patients reported they preferred being seen remotely rather than face-to-face. Qualitative data on patients’ thoughts about the service could be categorised into 4 themes: satisfaction with the interaction and service, conveniency, lack of clinical examination and satisfaction with the service given the current pandemic circumstances.

Conclusion: This survey has shown that patients were satisfied with their remote consultation and the majority thought it was an acceptable method of consultation. This also allowed patients to continue being seen during a period of COVID-19 lockdown and reduce patient footfall through the hospital. Overall feedback indicated very high levels of patient satisfaction with this service.

Keywords: COVID-19, ophthalmology, telemedicine, cornea

Introduction

Ophthalmology is the busiest outpatient specialty in the UK providing 8.2% of 96.4 million hospital outpatient attendances.1 The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a necessary reduction in clinic appointments and patient numbers in outpatient clinics to enable social distancing, as well as reduced patient attendance due to shielding at home.2 The pandemic has accelerated the use and implementation of remote healthcare worldwide.3,4 Virtual clinics, where the face-to-face clinician component is removed,5 are well established and increasingly being utilised to manage low-risk outpatient care such as glaucoma and medical retina clinics.6,7 Patients attend for investigations which are subsequently reviewed by a trained clinician remotely. They provide a safe and convenient method to assess suitable patients and reduce waiting times improving appointment capacity.8 The Royal College of Ophthalmologists released a guideline on the Standards for Virtual Clinics in Glaucoma in 20166 which defined the minimum standards for the development and implementation of virtual clinics for glaucoma management, however, there are no guidelines for virtual clinics in the assessment of other ophthalmic conditions in the UK. Due to the effects of the pandemic, a remote consultation clinic for stable ophthalmic patients was established to help address the increasing backlog of appointments and reduce the risk of infection transmission. Patient consultations were performed by video or telephone consultation, thereby avoiding the need for patients to come to the hospital. The purpose of this survey was to assess patient satisfaction with this remote ophthalmic clinic and identify areas of improvement.

Methods

The remote ophthalmic clinic was implemented for patients due a routine follow-up of stable conditions under the Corneal Service at Mid Cheshire NHS Hospitals. All patients awaiting an appointment were reviewed and triaged as to whether they were considered suitable for such a remote consultation. This was done by reviewing electronic patient letters and the electronic patient record (EPR) where available (Medisoft) and was carried out by an optometrist with several years of experience in seeing patients in the Corneal clinic. Patients deemed suitable were those who had been allocated a routine follow-up appointment time of six months or longer with conditions where symptoms play an important role in guiding management such as recurrent corneal erosion syndrome, meibomian gland dysfunction and Fuchs endothelial dystrophy.

Patients were sent a letter explaining how the consultation would take place, consultation date and time, what to expect on the day, instructions on how to access the internet web call (Attend Anywhere), and contact details for any concerns (Supplementary information). A College of Optometrists home sight test was included with the letter to check their vision at home prior to the appointment.9 Where the patient was willing and able to connect to the NHS Attend Anywhere service, this was used for video consultation. If the patient did not connect to this then the patient received a telephone call and the consultation was performed over the phone. Consultations were carried out by the Corneal consultant or the trained optometrist.

A telephone survey was developed on Microsoft Forms. Approval and validation of the survey was gained from the Patient Experience and Survey department at Mid Cheshire NHS Hospitals. Consecutive patients who had remote consultations from September 2020 until November 2020 were identified from clinic lists and were interviewed between 4 and 8 weeks after their appointment over a 2-week period. Patient demographics and appointment details were obtained from the EPR and recorded prior to each telephone call. This consisted of age, sex, appointment type, clinician, diagnosis, follow-up type and follow-up duration. All surveys were conducted by a single independent assessor who was not part of the patients’ clinical care team. This assessor made contact with the survey patients by telephone call. The survey followed the same structured format for all patients: introduction of the assessor as a member of the local eye department, consent to perform the telephone survey, survey questions, and consent to use the data anonymously. Data were inputted into Microsoft Forms (Figure 1). The first 3 questions sought to assess patient satisfaction with their remote consultation and how happy they would be for their subsequent appointment to be performed remotely. The final question was an open response to assess patients’ thoughts about the service which was recorded verbatim.

|

Figure 1 Patient satisfaction telephone survey questions. |

Results

Over the 8-week assessment period from September - November there were 89 patients that had been scheduled for the clinic. Of these, 5 were not contactable at the time of their appointment. Attempts were made to include the remaining 84 patients in the survey, of whom 51 patients completed the survey giving a response rate of 60.7% (30 patients could not be contacted; 2 did not remember their appointments; 1 did not want to participate in the survey).

Patient Demographics

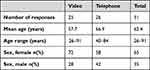

The mean age was 62.4 years with a range between 26 and 91 years. Thirty-three (64.7%) patients were female and 18 (35.3%) were male. Twenty-six (51.0%) patients had a telephone consultation and 25 (49.0%) had a video consultation. Thirty-two (62.7%) patients were seen by an ophthalmic consultant and 19 (37.3%) by the optometrist. Patient demographics are shown in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Patient Demographics |

Diagnoses and Follow-Up

The most common diagnoses were dry eyes and Fuchs endothelial dystrophy. Sixteen (31.3%) patients were discharged and only 2 patients had to be reviewed in <1 month. Further diagnoses and follow-up data have been included in Supplementary information.

Technical Issues

There were technical difficulties in 3 cases where video consultations had to be changed to telephone consultations. Additionally, 1 patient expressed difficulty with a virtual consultation due to having a cochlear implant.

Patient Satisfaction with Remote Consultation

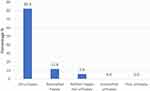

Forty-two (82.3%) patients reported they were very happy with the virtual appointment; 6 (11.8%) somewhat happy and 3 (5.9%) were neither happy nor unhappy (Figure 2). In total, 94.1% reported satisfaction with their virtual appointment.

|

Figure 2 Patient responses for patient satisfaction (%). |

Patient Satisfaction with Subsequent Remote Consultation

In total, 36 patients (70.5%) reported satisfaction for a subsequent virtual appointment with 32 (62.7%) reporting very happy, and 9 (17.7%) reported dissatisfaction with 6 (11.8%) being very unhappy (Figure 3).

|

Figure 3 Patient responses for satisfaction with subsequent remote consultation (%). |

Patient Preference for Face-to-Face Appointment versus Remote Consultation

Thirty-three (64.7%) patients reported they preferred being seen by remote consultation. Sixteen (31.4%) patients reported they would have preferred being seen face-to-face with 11 (21.6%) responding definitely yes. (Figure 4).

|

Figure 4 Patient preference for physical face-to-face appointment versus remote appointment. |

Patient Thoughts

Qualitative data collected by asking patient their thoughts on the service could be categorised into 4 themes (Table 2). Patients expressed:

- Satisfaction with the interaction/service

- Conveniency of the service

- Lack of clinical examination in a remote consultation

- Satisfaction with the service given the current pandemic

|

Table 2 Main Themes Identified and Patient Responses |

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has had and is still having profound consequences across the globe, particularly for health care delivery. As health systems in many countries have struggled to cope with caring for large number of people infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus, the effect on routine services has been disquieting. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists in the UK had already previously highlighted that patients were losing vision due to delays in treatment and follow-up appointments before the pandemic,10 this situation has been greatly exacerbated by COVID-19.11

This remote consultation service was developed to help address the reduction in outpatient appointment capacity due to social distancing and pandemic lockdown measures. Overall, this survey showed very high levels of patient satisfaction with this service. Ninety-four percent of respondents reported they were happy with their remote consultation, the vast majority of these being very happy. This percentage is comparable to the “NHS Friends and Family test”, the national feedback tool assessing whether patients would recommend the service used, and in which 94% of respondents recommended their outpatient service before the pandemic.12 Seventy-one percent of respondents answered that they would be very happy with a subsequent remote consultation and almost two-thirds also responded that they preferred being seen remotely.

Qualitative data collected about patients’ thoughts on the service indicated that patients were satisfied with their consultation and in some cases that they would not have otherwise attended due to being in a vulnerable group during the pandemic. Additionally, the convenience of the service saved them from having to travel long distances and take time off work. Some patients did prefer a physical face-to-face appointment, but most of these were willing to tolerate a remote consultation given the current pandemic. However, others responded that with the increase in working from home, remote meetings and calls have become the new norm, and as such this method of consultation should be increasingly used. Patients also responded that they had previously had remote consultations with other medical specialties and were comfortable with using this as a method for consultation.

Our patient satisfaction survey indicates patients were satisfied with their remote consultation and the majority thought it was an acceptable method of consultation for self-evaluable corneal conditions. This agrees with previous literature about glaucoma virtual clinics: A patient feedback survey of a newly developed virtual glaucoma service in 2015 showed that the majority of respondents found aspects of the service to be excellent or satisfactory and less than 3% reported a poor experience.13 In a national survey in 2018 of the use of a virtual glaucoma service, the majority of consultant ophthalmologists perceived glaucoma virtual clinics to be acceptable to patients, with efficiency and patient safety to be at least equivalent to usual care.8 For this virtual glaucoma service, however, patients attend the hospital eye service for tests to be carried out, often by nursing staff, which are subsequently reviewed by a clinician.

In comparison to a glaucoma service where clinical measurements and imaging need to take place, this service follows a simpler model in which a consultation is performed by video or telephone consultation. Additionally, it allows for training of allied health care professionals such as optometrists to have an increased role in the management of patients with patient safety maintained by supervision from an ophthalmic consultant. A key limitation is, of course, the inability to perform a clinical examination. Subjective changes in visual function, visual acuity, and symptomatology can be easily assessed, and with video consultation, prominent examination findings such as lid swelling and the amount of conjunctival hyperaemia are examinable however more subtle findings such as corneal neovascularisation are not assessable. Additionally, as patients were recruited from the corneal service, this model may not be as useful for other ophthalmic specialties.

A very important factor is, therefore, the initial triaging of patients to ensure only suitable patients are seen in this remote service. It was interesting to note that almost one-third of patients were discharged from hospital eye service follow-up after the remote consultation. Many of these, however, would have continued under community optometry review. Almost a half of patients went on to have a clinic appointment and one-fifth had a subsequent remote consultation. The lack of clinical examination may be overcome by alternating remote consultations and face-to-face appointments to allow ongoing management as well as maintain the remote service.

Conclusion

This survey has shown that patients were satisfied with their remote consultation and the majority thought it was an acceptable method of consultation for self-evaluable ophthalmic conditions. The main benefits identified were convenience of the appointment and patient satisfaction with the healthcare interaction. Review of patients with restrictions due to social distancing and shielding at home could be conducted, albeit without a proper clinical examination. This model of care allowed capacity for other patients who needed a full assessment to be seen in the clinic. Patients were supportive of using this service in conjunction with face-to-face clinic appointments to improve patient experience and department capacity.

Ethical Approval

This survey is categorized as service evaluation and thus ethical approval by a research ethics committee was not required as per the National Health Service Health Research Authority guidelines in the United Kingdom. Approval was sought by an advisory group from the Patient Experience and Survey department at Leighton Hospital, Mid Cheshire NHS Hospitals Foundation Trust. This survey was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was gained from patients to participate in the survey and no patient identifiable information is included in the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. NHS Digital. Hospital outpatient activity 2019–20 [Internet]; 2020. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/hospital-outpatient-activity/2019-20.

2. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Protecting patients, protecting staff [Internet]; 2020. Available from: https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Protecting-Patients-Protecting-Staff-UPDATED-300320.pdf.

3. Hawrysz L, Gierszewska G, Bitkowska A. The research on patient satisfaction with remote healthcare prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5338. doi:10.3390/ijerph18105338

4. Nair AG, Gandhi RA, Natarajan S. Effect of COVID-19 related lockdown on ophthalmic practice and patient care in India: results of a survey. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68(5):725–730. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_797_20

5. Kotecha A, Brookes J, Foster PJ. A technician-delivered “virtual clinic” for triaging low-risk glaucoma referrals. Eye. 2017;31(6):899–905. doi:10.1038/eye.2017.9

6. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Standards for virtual clinics in glaucoma care in the NHS Hospital Eye Service [Internet]. Ophthalmic Services Guidance; 2016. Available from: https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2017/03/Virtual-Glaucoma-Clinics.pdf.

7. Kortuem K, Fasler K, Charnley A, et al. Implementation of medical retina virtual clinics in a tertiary eye care referral centre. Br J Ophthalmol. 2018;102(10):1391–1395. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-311494

8. Gunn PJG, Marks JR, Au L, et al. Acceptability and use of glaucoma virtual clinics in the UK: a national survey of clinical leads. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2018;3(1):e000127. doi:10.1136/bmjophth-2017-000127

9. The College of Optometrists. Home sight test chart [Internet]; 2020. Available from: https://www.college-optometrists.org/the-college/media-hub/news-listing/covid-19-patient-support-during-lockdown.html.

10. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. BOSU report shows patients losing sight to follow-up appointment delays [Internet]; 2017. Available from: https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/2017/02/bosu-report-shows-patients-coming-to-harm-due-to-delays-in-treatment-and-follow-up-appointments/.

11. Poyser A, Deol SS, Osman L, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on eye emergencies. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2020;31:2894–2900.

12. NHS. Friends and family test [Internet]; 2020. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/friends-and-family-test-data-february-2020/.

13. Kotecha A, Baldwin A, Brookes J, et al. Experiences with developing and implementing a virtual clinic for glaucoma care in an NHS setting. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;9:1915–1923. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S92409

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.