Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

Parental Socialization and Adjustment Components in Adolescents and Middle-Aged Adults: How are They Related?

Authors Martinez-Escudero JA , Garcia OF , Alcaide M , Bochons I , Garcia F

Received 3 November 2022

Accepted for publication 9 March 2023

Published 10 April 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 1127—1139

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S394557

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Jose Antonio Martinez-Escudero,1 Oscar F Garcia,2 Marta Alcaide,1 Isabel Bochons,3 Fernando Garcia1

1Department of Methodology of Behavioral Sciences, Faculty of Psychology, University of Valencia, Valencia, 46010, Spain; 2Department of Developmental and Educational Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, University of Valencia, Valencia, 46010, Spain; 3Department of Developmental and Educational Psychology, Faculty of Teacher Training, University of Valencia, Valencia, 46010, Spain

Correspondence: Oscar F Garcia, Department of Developmental and Educational Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, University of Valencia, Valencia, 46010, Spain, Tel +34 963983846, Email [email protected]

Purpose: Classic studies mainly of European-American families broadly identify the benefits of parental strictness combined with parental warmth. However, current research tends to identify parental warmth as positive for adjustment, even without parental strictness. In addition, less is known about the relationship between parenting and adjustment beyond adolescence. The present study examined warmth and strictness and its relationship with self, sexism, and stimulation values. Self-esteem, academic-professional self-concept, benevolent sexism, and stimulation values were used to capture adjustment.

Patients and Methods: Participants (n = 1125) were adolescents and adult children of middle-age from Spain. The statistical analyses used were correlation analysis and multiple linear regression.

Results: In general, the relationship between parenting and adjustment was found to have a similar pattern for adolescent and middle-aged adult children, although more marked in adolescents. Parental warmth and strictness were predictors of adjustment, but in a different direction. Specifically, parental warmth positively predicted academic-professional self-concept and self-esteem, whereas parental strictness was detrimental as a predictor of higher benevolent sexism.

Conclusion: Overall, the present findings suggest that an effective socialization during the socialization years and even beyond can be positively predicted by parental warmth, whereas parental strictness might be unnecessary or even detrimental.

Keywords: parenting, parental socialization, family, adjustment, adolescence, adulthood

Introduction

The socialization process takes place in different contexts in which several agents participate such as parents,1 peers,2 teachers,3 and the media.4 Parental socialization is the process of transmitting social values or standards with the objective that the child, who is immature and dependent, when reaching the adult age becomes a mature adult, autonomous, and adjusted to social demands.5–7 Once the children reach adult age, they and their parents are both adults.8,9 Adult children tend to maintain the relationship with their parents,10 while continuing their development in the areas of work, partnership, and even becoming parents themselves.11–13 An important question is to know the relationship between parenting dimensions and child adjustment during parental socialization, for example, in adolescence but also when parental socialization is ended, such as in middle-life.

Much of the studies on parenting use the two-dimensional model, based on two theoretically orthogonal or non-related dimensions: warmth and strictness.14–17 Parental warmth refers to parental love, support, and acceptance. It represents the degree to which parents show their children warmth and acceptance, give them support, and communicate reasoning with them.18,19 On the opposite side, parental strictness is also known as discipline or rigor as parents control their children’s behavior by maintaining an assertive authority position with their children.18,20

Parents can be characterized by two main dimensions: warmth and strictness.14,17,21,22 Within parents defined by higher levels of warmth, those characterized by high strictness or authoritativeness have been distinguished from those characterized by low strictness or indulgentness. Authoritative families are close and involved and use reasoning with their children, but, at the same time, they are strict and tend to use authority and punishment to correct misbehavior. The indulgent families are also close and involved in parenting and use reasoning as a way of correcting their children but without using punishment and imposition.14,23,24 Within parents defined by lower levels of warmth, those characterized by high strictness or authoritarian homes have been distinguished from those characterized by low strictness or neglectful homes. Both families share low involvement, less love and warmth, and less use of reasoning and dialogue. In addition, authoritarian families use correction and authority, without reasoning when their children misbehave.14,23,24

Family studies examine the relationship between parenting and child adjustment. Overall, according to the studies mainly carried out with European-American families, only greater parental strictness when is combined to greater parental warmth (ie, the authoritative style) tends to be related to the highest child adjustment.6,8,23,25–30 Children benefit from high levels of parental strictness combined with high levels of parental warmth reporting good self-perceptions23,29 and self-esteem,31,32 fewer behavioral problems23,26 and a good social adjustment28,29 and greater internalization of norms.23,29 Nevertheless, the combination of greater levels of warmth and strictness are not always associated with the highest adjustment in all cultural contexts.15–17,33–35 Some studies revealed some benefits of higher parental strictness accompanied by low warmth in ethnic minority families from US such as African-American35,36 and Chinese-American34,37 as well as in those from Arab Societies.38–40

Additionally, emergent studies mainly conducted in European and South American countries revealed the benefits of parental warmth but with lower parental strictness on child adjustment.4,16,17,41–50 Children raised in homes characterized by high warmth with low strictness (ie, the indulgent style) showed the greatest adjustment in different indicators such as self,43,46 maturity,17 less problems and better social adjustment,47,48 school achievement,16,48 and internalization of social values.43,44

Among the objectives of socialization are that children achieve self-confidence and a good self-perception, as well as an adequate social adjustment to social demands and the internalization of social values. Within self-perceptions, self-esteem as the global dimension and self-concept as the specific components have been distinguished.32,51–54 Self-esteem and self-concept have been considered important indicators of psychosocial adjustment in children, adolescents, and adults across cultural contexts,31,32,43,55–60 although some scholars have described differences in self-concept scores across ethnic and cultural contexts.56,61 Self-concept, defined as a person’s perception of self in different domains, is formed through experiences with the environment,62 and it is influenced by environmental reinforcement and significant others, such as parents.52,56,57 Specifically, academic/professional self-concept, defined as self-perceptions of competence in school and work, is positively related to academic performance and success in high school and college studies, as well as in work and career.52,53,56,63

Furthermore, a good adaptation to any cultural context requires a great adjustment of the individual to the demands of society.11,14–17 Prejudice represents a drastic form of poor adaptation to the demands of society. Sexism is a prejudice against women, which is related to high maladaptation64–66 and even to a higher probability of aggressive behavior.67,68 Sexism, in general terms, has been related to attitudes that legitimize violence against women.64,65 This is particularly benevolent sexism, which according to the theory of ambivalent sexism is conceptualized as a set of beliefs about women and their relationship to men that are subjectively positive but are stereotyped by seeing women in restricted roles.66,69

Additionally, the internalization of social values represents the individual identification with their own society, so that the socially acceptable behavior is motivated by internal and not external factors, is one of the main objectives of parental socialization,14,15,70 and it has been identified as the key to obtaining well-developed children.6,17,44,50,71,72 It has also been observed that parenting differentially affect children’s internalization of values.70,72 Within social values, stimulation values derive from the organismic need for variety and stimulation.73,74 The stimulation values help to maintain an optimal, positive, rather than threatening, level of activation. In this sense, stimulation values are related to the need underlying self-direction values.74,75

The Present Study

The present study analyzes the relationship between warmth and strictness parenting dimensions with child adjustment in adolescents and also in middle-aged adults. Most of parenting studies have focused on socialization years (ie, childhood and adolescence),6,17,23,27 but less is known about the if the relationship between parenting dimensions and child adjustment shows a similar pattern once parenting is ended, in adult children of middle years. In particular, family studies with middle-aged adults tend to be focused on their developmental task as parents and their relationship with their children, who are often adolescents76–78 or with their parents, who are usually older adults.12,79–82 However, less has been explored for middle-aged adults as adult children in their relationship with their parents during socialization years based on warmth and strictness. Even when examining parenting and adjustment in middle-life, middle-aged adults and adolescents who are raised by their parents have not been compared at the same time based on the main parenting dimensions and using the same outcomes or criteria for the comparisons.83

The present study aims to examine the relationship between parental warmth and strictness with self (academic/professional self-concept and self-esteem), benevolent sexism, and stimulation values in adolescents and middle-aged adults. It is expected that parental warmth would be related to greater scores in adjustment in terms of greater scores in self and values and lower in benevolent sexism. By contrast, it was also expected that parental strictness would not be associated with adjustment.

Materials and Methods

Design and Setting

The design includes four independent variables, parental warmth, parental strictness, age, and sex, as well as four dependent variables, which were academic-professional self-concept, self-esteem, benevolent sexism, and stimulation values. The methodology of the present study is non-experimental as in most of previous parenting studies conducted with a community sample in US23 and Europe48 but also in non-western setting such as Arab Societies.38 The study was conducted in a European country: Spain. Participants were attending from high school or from middle-class neighborhoods in a Spanish city of approximately one million inhabitants.

Participants and Recruitment

The study was based on adolescent children and adult children of midlife. There are different criteria to define age groups, especially adolescence,84,85 for example, a recent proposal suggests adolescence up to 24 years of age.86 However, age groups for adolescents and middle-aged adults were defined based on previous parenting studies. Adolescent children were participants aged 12 to 18 years,87,88 while adult children from midlife were participants aged 36 to 59 years.89,90 The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) they were Spanish, as well as their parents and grandparents; (b) lived in two-parent nuclear families with a mother or primary women caregiver and a father or primary male caregiver.

The sampling method for the participants (adolescents and middle-aged adults) was as follows: Adolescent participants were recruited from the full list of high schools (six were selected and one of them refused to participate). For this purpose, the principals of each high school invited to participate were contacted. If high school refused to participate, a replacement high school was elected from the full list until the required sample size was reached.42,47 Middle-aged respondents were recruited from randomly selected middle-class neighborhoods. The selection of middle-aged respondents was based on door-to-door canvassing. The different neighborhoods were stratified by quartiles of household wealth, and four middle-class neighborhoods were randomly selected. This sampling method is usually used with middle-aged adults in community studies.91,92

Measures

Parental Socialization

Parental socialization was assessed under two main dimensions (ie, warmth and strictness). Warmth was measured with 20 items from Warmth/Affection Scale (WAS).93 This scale measures the degree to which children perceive their parents as warm and affectionate (eg, “Say nice things about me”). WAS adult version measures the degree to which adult children had perceived their parents as warm and affectionate and has all items written in the past tense (eg, “Said nice things about me”). The alpha value was 0.945. Strictness was measured with 13 items from Parental Control Scale (PCS).93 This scale measures the degree to which children perceive their parents as controlling and strict (eg, “It make sure that I know exactly what I can and can not do”). The PCS adult version measures the degree to which adult children had perceived their parents as controlling and strict and has all items written in the past tense (eg, “It made sure that I knew exactly what I could and could not do”). The alpha value was 0.907. For the two scales, responses were given on a 4-point scale from 1 (“almost never true“) to 4 (”almost always true”). In general, studies with adult children use the same measures to assess parenting as the one used for adolescent children, but the items are written in the past tense, as in WAS and PCS scales94 but also in other questionnaires.95,96 The WAS and PCS scales are reliable and valid measures for children to assess parental socialization, ie, the degree of warmth and strictness used by their parents in the socialization process and beyond.94,97,98 Higher scores on the WAS and PCS scales represent a higher degree of parental warmth and strictness.99

Adjustment

The academic-professional self-concept was measured with the 6-item subscale of the Form 5 Self-Concept Scale [AF5].100 This dimension of the self includes how one perceives oneself in the academic/professional context (eg, “I do my homework well [professional works]”), and how one feels that one’s teachers/superiors value one’s performance (eg, “My superiors [teachers] think that I am a hard worker”). Participants responded on a scale of 1 to 99, being 1 (strongly disagree) and 99 (strongly agree). The higher the score on the scale, the higher the academic-professional self-concept. The alpha value was 0.902. The AF5 questionnaire has been widely applied in adolescents42,43,46 and adults.9,24,101 Exploratory analyses100 and confirmatory factor analyses102–104 have been carried out and have proven the invariance in the dimensional structure of the AF5 in different cultural contexts such as Spain,103 Portugal,105 Brazil,52 Chile,101 United States,106 and China.56 Besides, its invariance by sex and age has been validated in several studies across different languages, such as Brazilian-Portuguese,52 Portuguese,105 Chinese,56 and English106 with the Spanish version.

Self-esteem was measured with the 10-item Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale [RSE].51 This scale assesses the extent of self-acceptance and self-respect (eg, “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself”). Participants responded on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The higher the score on the scale, the higher the self-esteem. The alpha value was 0.848. This scale is one of the most widely used measures of global self-esteem.107

Benevolent sexism was measured with the 11-item subscale of the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory Scale [SAS].65 This scale assesses the extent of benevolent sexism understood as “viewing women stereotypically and in restricted roles, but are subjectively positive in feeling tone (for the perceiver) and also tend to elicit behaviors typically categorized as prosocial (eg, helping) or intimacy-seeking (eg, self-disclosure)”65 p. 491. A sample of item is “Many women have a quality of purity that few men possess.” Participants responded on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The higher the score on the scale, the higher the benevolent sexism. The alpha value was 0.875.

Stimulation values were measured with the 3-item subscale of the Schwartz’s Values Inventory [VAL].108 This scale assesses the excitement, novelty, and challenge in life (eg, “A variegated life [Full of challenges, changes and surprises]”). Participants responded on a scale of 1 to 99, being 1 (strongly disagree) and 99 (strongly agree). The higher the score on the scale, the higher the stimulation values. The alpha value was 0.770.

Data Collection

Power analysis was calculated with G*Power, a statistical program widely used in previous studies.109,110 A priori power analysis showed that with a small effect size (R2 = 0.010, R = 0.100), assuming a type I error probability of 0.05 and a power of 0.95, a sample of 1302 is required to find statistically significant differences.109,111 However, the sensitivity analysis showed that with the sample size of the study (n = 1125) and assuming a probability of type I error of 0.05 and a power of 0.95, statistically significant differences can be found with a small effect size (R2 = 0.016, R = 0.128).112,113

Data were collected through online questionnaires with mandatory responses that participants completed during 2020–2021 and 2021–2022 academic years. The data collection tools contains an online survey that includes all measures (parental socialization, academic-professional self-concept, self-esteem, benevolent sexism, and stimulation values) and demographic basic data (ie, age and sex). It was mandatory to answer all the items of the online survey. Additionally, it should be considered that respondents (a) participated voluntarily; (b) informed consent was requested; (c) anonymity of responses was warranted; and (d) parental consent was obligatory for adolescent participation. To warrant anonymity of responses, identifiers and survey data were deposited in independent files and directory passwords were protected, and sensitive files were coded.

The questionnaires were screened for questionable response patterns,101,104 and those participants whose responses were questionable were eliminated. About 1.6% (n = 18) of the participants were deleted from the sample due to questionable response patterns such as implausible inconsistencies between negatively and positively formulated responses.

Research Ethics Committee Approval or Ethical Consideration

The investigation was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The research project was approved by the College Research Ethics Committee (CREC) of Nottingham Trent University (protocol code No. 2017/90, May 2017) for studies involving humans.

Data Analysis

Correlation and multiple linear regression analysis were performed. Correlation analysis was performed between the two main parenting dimensions (warmth and strictness) and four child adjustment criteria (academic-professional self-concept, self-esteem, benevolent sexism, and stimulation values) that were measured separately for adolescent and middle-aged children. In addition, a linear regression was applied in which the predicted variables were the four child adjustment criteria (academic-professional self-concept, self-esteem, benevolent sexism, and stimulation values) and the predictors were the two main parenting dimensions (ie, warmth and strictness), age and sex.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

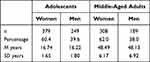

The present study was composed of a sample of 1125 participants (687 women, 61.1%, and 438 males, 38.9%; M = 30.59; SD = 16.43) that included adolescent children and middle-aged children. The adolescent children group consisted of 628 participants (56%) aged from 12 to 18 years (M = 16.53; SD = 1.72); the sex distribution of the adolescent children group was 379 women (60.4%) and 249 men (39.6%). On the other hand, the middle-aged group was composed of 497 participants (44%) aged from 36 to 59 years (M = 48.36; SD = 6.46); the sex distribution of the middle-aged group was 308 women (62.0%) and 189 men (38.0%). Age-specific and sex-specific descriptives were as follows: for adolescent women, M = 16.74, SD = 1.65; for adolescent men, M = 16.22, and SD = 1.80; for middle-aged women, M = 48.49, SD = 6.17, and for middle-aged men, M = 48.13, SD = 6.92 (see Table 1).

|

Table 1 Participants Characteristics for Age, Sex, and Frequency |

Relation Between Study Variables

The results of the correlation analysis between parenting dimensions (ie, warmth and strictness) and the four child adjustment criteria (academic-professional self-concept, self-esteem, benevolent sexism, and stimulation values) are presented in Table 2. Some statistically significant correlations were found between the parenting dimensions and the four criteria named above.

|

Table 2 Correlations Between Parental Dimensions and Child Adjustment# |

In general, in both adolescent and middle-aged children, parental warmth was positively related to adjustment scores, giving positive correlations with academic-professional self-concept and self-esteem. On the contrary, parental strictness seems to be related to mixed results in adolescents, with more costs than benefits. Specifically, a high degree of strictness correlated negatively with academic-professional self-concept and positively with greater benevolent sexism. At the same time, more strictness is related to greater stimulation values, even though the value of the correlation is low. Among middle-aged adults, parental strictness did not show any relation to the different criteria of child adjustment.

Additionally, some child adjustment criteria were positively correlated between them. In the case of adolescents, a positive correlation was observed between academic-professional self-concept, self-esteem, and stimulation values. A negative correlation was also observed between benevolent sexism and academic-professional self-concept. In the case of middle-aged adults, it was found that the higher the academic-professional self-concept, the higher the self-esteem, and the lower the benevolent sexism. In addition, benevolent sexism was related to worse scores in academic-professional self-concept and self-esteem.

Relation Between Parenting and Adjustment

The results of the linear multiple regression analysis were similar to those obtained in the correlation analysis. Results for the predictions of the four criteria (academic-professional self-concept, self-esteem, benevolent sexism, and stimulation values), as a function of parenting dimensions (ie, warmth and strictness) and age and sex are presented in Table 3.

|

Table 3 Multiple Linear Regression Coefficients Between Parenting Dimensions, Sex, and Age and Child Adjustment |

A multiple linear regression model was performed for each dependent variable. In general, the different parenting dimensions predicted the child adjustment criteria. In both the correlation and regression analyses, a common pattern was observed: parental warmth was positively related to child adjustment, while parental strictness was not related to child adjustment and may even be negatively associated with child adjustment.

The four models for regression reached a statistically significant level (p < 0.05). Parental warmth and strictness were predictors of adjustment, but in a different direction. Parental warmth was a significant positive predictor of academic-professional self-concept and self-esteem, whereas parental strictness did not reach a statistically significant level in most of the criteria. Greater scores on academic-professional self-concept and self-esteem were predicted by parental warmth. However, strictness alone did not positively predict any criteria and was even a significant predictor of benevolent sexism. Higher scores on benevolent sexism were predicted by parental strictness.

Relation Between Age and Sex with Adjustment

In general, age and sex also predicted child adjustment criteria. On the one hand, age was a statistically significant positive predictor of academic-professional self-concept and self-esteem and a negative predictor of stimulation values. Thus, among middle-aged adults in comparison to adolescents, their scores were higher on academic-professional self-concept and self-esteem, but lower on stimulation values. On the other hand, sex was a statistically significant predictor for academic-professional self-concept, self-esteem, benevolent sexism, and stimulation values. Men reported higher scores on self-esteem, benevolent sexism, and stimulation values, while women had greater scores on academic/professional self-concept.

Discussion

The present study examined the relationship between parental socialization and the adjustment of adolescent and middle-aged adult children. The results showed that the dimensions of parental socialization were consistently related to children’s adjustment. While parental warmth was beneficial to children’s adjustment, parental strictness was unrelated to or even detrimental to adjustment.

On the one hand, correlational analyses for adolescent and middle-aged adult children revealed that they showed a similar pattern in the relationship between parental dimensions (ie, warmth and strictness) and adjustment, although more marked in adolescents. On the other hand, regression analyses allowed statistically significant predictions of differences in self-esteem, professional academic self-concept, and benevolent sexism as a function of socialization type. Thus, parental warmth was a positive predictor of self-esteem and academic/professional self-concept. According to this prediction model, the more warmth during socialization, the higher the general self-esteem (self-esteem) and academic/professional self-perceptions (self-concept). Parental strictness was not a statistically significant predictor, and even benevolent sexism reached statistical significance as a predictor of greater scores. Thus, the higher the levels of strictness, the greater the predisposition to sexism against women. Some studies have examined parental socialization beyond adolescence, mainly with young adults41,114,115 and, to a lesser extent, middle-aged adults.83 According to previous studies, parental socialization, even beyond adolescence, shows a pattern consistent with the adjustment of adult children compared to children and adolescents. The present findings confirm some previous studies that the relationship between parenting and adjustment is quite similar for adolescents and adult children of middle-aged, although more marked in adolescents. Additionally, the present study adds new evidence by examining parental socialization in adolescent and middle-aged adult children at the same time and using the same adjustment criteria.

Previous research has linked parenting (which is examined through warmth and strictness) and child and adolescent adjustment. The results of the present study are consistent with a growing body of research, conducted primarily in European and Latin American countries, that identifies the broad benefits of warmth without strictness (the indulgent parenting).16,17,44,45,48,90 Consistent with this previous evidence, the results of the present study identify the benefits of parental warmth, which allow the child to obtain good adjustment, in terms of confidence in oneself as a valuable member of the society (ie, self-esteem) and good perception of his or her school and professional performance (ie, academic/professional self-concept). Parental strictness seems unnecessary or even detrimental due to it leads to an increase in prejudice against women in subtle ways (ie, benevolent sexism).

It is important to note that the findings of the present research do not coincide with those mainly from middle-class European-American families. According to these studies, only the combination of high strictness and high warmth is always beneficial for children’s adjustment. In this sense, mainly for a good adjustment to social demands, few behavioral problems and good internalization of norms, children from strict families obtain the highest scores.23,25,28 However, the present study shows that parental strictness positively predicts benevolent sexism, a form of lack of adjustment to norms associated with maladjustment or even aggressive behavior. Given this new evidence that questions classic results, mainly from research with European-American families, it is especially important to analyze parental socialization in different cultural contexts because the combination of warmth and strictness (authoritative parenting) may not always be the most beneficial.15,33,35

Likewise, age and sex were included in the regression models. In relation to age, it was a positive predictor of professional self-concept/academic and self-esteem and a negative predictor of stimulation values. Thus, middle-aged adults, compared to adolescents, showed better scores in self (self-esteem and academic/professional self-concept) but also lower priority for stimulation values than adolescents. Sex was a predictor of self-esteem, academic/professional self-concept, benevolent sexism, and stimulation values. Thus, the regression models predicted higher academic/professional self-concept in women, whereas, in men, greater self-esteem, benevolent sexism, and stimulation values.

There comes a time when the adolescent reaches adult age and parental socialization ends. Middle-aged adults probably have developed their professional career, they have a couple and perhaps their own family, being parents. The findings from this study reveal differences between middle-aged and adolescents given that they are at different life stages, middle-aged adults showing more academic/professional self-concept and self-esteem, and adolescents more priority for stimulation values. Many family studies have studied middle-aged adults in relation to their parents (older adults)79,82 or their children (probably adolescents),76,77 although this study focuses on the socialization process when they were raised by their parents. However, according to the present study, adult children even in middle age, like adolescents, benefit from a good self-esteem and academic/professional self-concept, which are key to functioning in society, if their families have been involved (high parental warmth). However, if they have been raised in families characterized by imposition (high parental strictness), they tend to show any benefit and even more mismatch in terms of benevolent sexism. This study shows that, even some time after socialization, there may be differences in adjustment also related to the type of family.

The present study has some important strengths. First, this study examined family socialization using an established theoretical framework: the two-dimensional model.14 In addition, most studies related to parental socialization have been conducted with samples of adolescents.4,16,23,29 In contrast, this model allows us to know in detail and in greater depth what are the positive or negative correlates of parental socialization, while it is taking place and once it has ended. In this way, predictions of children’s adjustment can be made as follows: parental warmth during the socialization years would always be positive for adjustment, whereas parental severity would be unnecessary or even detrimental. In addition, this study adds new evidence focusing on middle-aged adults. This study is conducted based on four indicators that are relevant to the development of adolescents and middle-aged children: self-esteem, academic/professional self-concept, benevolent sexism, and stimulation values.

However, some limitations should be considered. Due to the long-time from parental socialization in middle-aged children, caution is advised because the study is not based on longitudinal data but is a cross-sectional study. However, a consistent pattern is observed between the dimensions of parental socialization (ie, warmth and strictness) and children’s adjustment. Future follow-up studies should analyze the consequences of parental socialization by following the evolution of adult children during adulthood. Additionally, it is worth mentioning that no experimental methodology was followed in conducting this study.

The results of the present study do not completely coincide with those of classic studies, mainly of European-American families, in which it is found that the combination of high warmth and high strictness has a beneficial impact on adjustment.23,29 Therefore, when studying the relationship between the parental dimensions, which are warmth and strictness, with adjustment components, the cultural context in which socialization occurs must be considered.15,17,33 The main question of whether authoritative parenting is associated with universal benefits requires extending the study of parental socialization across the globe; different countries or cultural settings should be compared at the same time to identify optimal parenting using invariant measures so that the results are comparable. Furthermore, within the same society, different contexts, such as poverty and at-risk neighborhood, should be considered, or the correlates of parenting among children with different characteristics, such as school underachievement or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), should be examined. Future studies should conduct longitudinal follow-ups of adult children after parental socialization, despite the difficulties associated with follow-up. In addition, it seems relevant to examine parental socialization beyond adolescence; future research with adult children could use specific features of adjustment outcomes such as romantic relationship quality and identity status in young adulthood, parental stress and marital satisfaction in middle adulthood, and ego integrity and care for grandchildren in late life.

Implications for Practice

The present findings on the relationship between parental socialization and adjustment in adolescence, but also in midlife, have important implications for practice. Any professional practice should be based on previous research. According to the present findings, the use of parental strictness seems unnecessary or even detrimental, despite the fact that it is widely identified as beneficial in previous studies conducted primarily with European-American parents23 and widely recommended in interventions with families.116 Current interventions may not be effective, at least in the European context, where, according to some emerging research, children benefit especially when they have relationships with their parents based on love, affection, and dialogue, but not on strict parenting practices.117,118

Interestingly, most interventions with families in professional practice are with adolescent children, partly because that is when they are likely to have the most problems.119 However, even after the socialization years, in adulthood there is also a relationship between adjustment and maladjustment with the type of family socialization. Therefore, professional practice focused on middle-aged adults may also be possible. Even if they do not have clinical problems, middle-aged adult children who grew up without parental warmth (affection, and involvement) are more likely to have adjustment problems. Especially for middle-aged adults, many of whom are involved in the difficult dual task of raising their children (in many cases, adolescents) and caring for their parents (likely older adults),120 an intervention based on life review of the socialization years might be especially helpful.121

Conclusions

The objective of parental socialization is for children to have maturity and independence when they reach adult age, when they are no longer under the care and supervision of their parents. A theoretical model based on two dimensions, warmth and strictness, has traditionally been used to study parental socialization.14 The results of the present study seem to suggest that parental socialization is related to children’s adjustment, not only while parents are raising their children but also beyond adolescence. Even when socialization is over, a similar pattern is observed in middle-aged children between parental dimensions and adjustment to that found in adolescent children, but less marked, probably because of other variables and adult developmental influences. Thus, when predicting adjustment not only in adolescence but also in adulthood (eg, middle age), the influence of the family during the socialization process should be considered. However, the dimensions of socialization do not predict adjustment in the same direction. According to the present study, parental warmth positively predicts adjustment, the more scores the greater the adjustment of children in terms of self-esteem and academic/professional self-concept. However, strictness was not beneficial and even predicted greater benevolent sexism, the stricter the parents were, the more sexist the children would be.

Acknowledgments

The research reported in this study has been partially supported by Grants CIAICO/2021/252 (Conselleria for Innovation, Universities, Science and Digital Society, Generalitat Valenciana), FPU20/06307 (Ministry of Universities, Government of Spain), ACIF/2016/431, and BEFPI/2017/058, which provided funding for a research stay at the Nottingham Trent University, UK (Generalitat Valenciana and European Social Fund).

Disclosure

Dr Oscar F Garcia reports grants from Generalitat Valenciana and grants from European Social Fund, during the conduct of the study. Marta Alcaide reports grants from Ministry of Universities, Government of Spain, during the conduct of the study. Professor Fernando Garcia reports grants from Conselleria for Innovation, Universities, Science and Digital Society, Generalitat Valenciana, during the conduct of the study. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Sandoval-Obando E, Alcaide M, Salazar-Muñoz M, Peña-Troncoso S, Hernández-Mosqueira C, Gimenez-Serrano S. Raising children in risky neighborhoods from Chile: examining the relationship between parenting stress and parental adjustment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(1). doi:10.3390/ijerph19010045

2. Musitu-Ferrer D, Esteban Ibáñez M, León C, Garcia OF. Is school adjustment related to environmental empathy and connectedness to nature? Psychosoc Interv. 2019;28(2):101–110. doi:10.5093/pi2019a8

3. Veiga FH, Festas I, Garcia OF, et al. Do students with immigrant and native parents perceive themselves as equally engaged in school during adolescence? Curr Psychol. 2021. doi:10.1007/s12144-021-02480-2

4. Garcia OF, Serra E, Zacares JJ, Calafat A, Garcia F. Alcohol use and abuse and motivations for drinking and non-drinking among Spanish adolescents: do we know enough when we know parenting style? Psychol Health. 2020;35(6):645–654. doi:10.1080/08870446.2019.1675660

5. Rudy D, Grusec JE. Correlates of authoritarian parenting in individualist and collectivist cultures and implications for understanding the transmission of values. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2001;32(2):202–212. doi:10.1177/0022022101032002007

6. Baumrind D. Parental disciplinary patterns and social competence in children. Youth Soc. 1978;9(3):239–276. doi:10.1177/0044118X7800900302

7. Garcia OF, Fuentes MC, Gracia E, Serra E, Garcia F. Parenting warmth and strictness across three generations: parenting styles and psychosocial adjustment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(20):7487. doi:10.3390/ijerph17207487

8. Baumrind D. Effective parenting during the early adolescent transition. In: Cowan PA, Herington EM, editors. Advances in Family Research Series. Family Transitions. Hillsdale, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1991:111–163.

9. Villarejo S, Martinez-Escudero JA, Garcia OF. Parenting styles and their contribution to children personal and social adjustment. Ansiedad Estres. 2020;26(1):1–8. doi:10.1016/j.anyes.2019.12.001

10. Steinberg L. We know some things: parent-adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. J Res Adolesc. 2001;11:1–19. doi:10.1111/1532-7795.00001

11. Maccoby EE. The role of parents in the socialization of children - an historical overview. Dev Psychol. 1992;28(6):1006–1017. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.28.6.1006

12. Kaufman G, Uhlenberg P. Effects of life course transitions on the quality of relationships between adult children and their parents. J Marriage Fam. 1998;60(4):924–938. doi:10.2307/353635

13. Umberson D. Relationships between adult children and their parents - psychological consequences for both generations. J Marriage Fam. 1992;54(3):664–674. doi:10.2307/353252

14. Maccoby EE, Martin JA. Socialization in the context of the family: parent–child interaction. In: Mussen PH, editor. Handbook of Child Psychology. Vol. 4. New York: Wiley; 1983:1–101.

15. Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as context: an integrative model. Psychol Bull. 1993;113(3):487–496. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.487

16. Garcia F, Gracia E. Is always authoritative the optimum parenting style? Evidence from Spanish families. Adolescence. 2009;44(173):101–131.

17. Garcia F, Serra E, Garcia OF, Martinez I, Cruise E. A third emerging stage for the current digital society? Optimal parenting styles in Spain, the United States, Germany, and Brazil. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(13):2333. doi:10.3390/ijerph16132333

18. Martínez I, Cruise E, Garcia OF, Murgui S. English validation of the Parental Socialization Scale—ESPA29. Front Psychol. 2017;8(865):1–10. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00865

19. Martínez I, García JF, Camino L, Camino C. Parental socialization: Brazilian adaptation of the ESPA29 scale. Psicol Reflex Crit. 2011;21(4):640–647. doi:10.1590/S0102-79722011000400003

20. Martinez I, Garcia F, Fuentes MC, et al. Researching parental socialization styles across three cultural contexts: scale ESPA29 bi-dimensional validity in Spain, Portugal, and Brazil. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(2):197. doi:10.3390/ijerph16020197

21. Martínez I, Murgui S, Garcia OF, Garcia F. Parenting and adolescent adjustment: the mediational role of family self-esteem. J Child Fam Stud. 2021;30(5):1184–1197. doi:10.1007/s10826-021-01937-z

22. Fuentes MC, Alarcón A, Gracia E, Garcia F. School adjustment among Spanish adolescents: influence of parental socialization. Cult Educ. 2015;27(1):1–32. doi:10.1080/11356405.2015.1006847

23. Lamborn SD, Mounts NS, Steinberg L, Dornbusch SM. Patterns of competence and adjustment among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful families. Child Dev. 1991;62(5):1049–1065. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01588.x

24. Martinez-Escudero JA, Villarejo S, Garcia OF, Garcia F. Parental socialization and its impact across the lifespan. Behav Sci. 2020;10(6):101. doi:10.3390/bs10060101

25. Steinberg L, Elmen JD, Mounts NS. Authoritative parenting, psychosocial maturity, and academic-success among adolescents. Child Dev. 1989;60(6):1424–1436. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1989.tb04014.x

26. Mounts N, Steinberg L. An ecological analysis of peer influence on adolescent grade-point average and drug-use. Dev Psychol. 1995;31(6):915–922. doi:10.1037//0012-1649.31.6.915

27. Baumrind D. Current patterns of parental authority. Dev Psychol. 1971;4(1, part 2):1–103. doi:10.1037/h0030372

28. Baumrind D. Child cares practices anteceding three patterns of preschool behavior. Genet Psychol Monogr. 1967;75(1):43–88.

29. Steinberg L, Lamborn SD, Darling N, Mounts NS, Dornbusch SM. Over-time changes in adjustment and competence among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful families. Child Dev. 1994;65(3):754–770. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00781.x

30. Steinberg L, Lamborn SD, Dornbusch SM, Darling N. Impact of parenting practices on adolescent achievement: authoritative parenting, school involvement, and encouragement to succeed. Child Dev. 1992;63:1266–1281. doi:10.2307/1131532

31. Barber BK, Chadwick BA, Oerter R. Parental behaviors and adolescent self-esteem in the United-States and Germany. J Marriage Fam. 1992;54:128–141. doi:10.2307/353281

32. Coopersmith S. The Antecedents of Self-Esteem. San Francisco: Freeman; 1967.

33. Pinquart M, Kauser R. Do the associations of parenting styles with behavior problems and academic achievement vary by culture? Results from a meta-analysis. Cultur Divers Ethni Minor Psychol. 2018;24(1):75–100. doi:10.1037/cdp0000149

34. Chao RK. Extending research on the consequences of parenting style for Chinese Americans and European Americans. Child Dev. 2001;72:1832–1843. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00381

35. Baumrind D. An exploratory study of socialization effects on Black children: some Black-White comparisons. Child Dev. 1972;43(1):261–267. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1972.tb01099.x

36. Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA. Externalizing behavior problems and discipline revisited: nonlinear effects and variation by culture, context, and gender. Psychol Inq. 1997;8(3):161–175. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli0803_1

37. Chao RK. Beyond parental control and authoritarian parenting style: understanding Chinese parenting through the cultural notion of training. Child Dev. 1994;65(4):1111–1119. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00806.x

38. Dwairy M, Achoui M. Introduction to three cross-regional research studies on parenting styles, individuation, and mental health in Arab societies. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2006;37:221–229. doi:10.1177/0022022106286921

39. Dwairy M, Achoui M, Abouserfe R, Farah A. Parenting styles, individuation, and mental health of Arab adolescents: a third cross-regional research study. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2006;37(3):262–272. doi:10.1177/0022022106286924

40. Dwairy M, Achoui M, Abouserie R, Farah A. Adolescent-family connectedness among Arabs: a second cross-regional research study. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2006;37:248–261. doi:10.1177/0022022106286923

41. Garcia OF, Lopez-Fernandez O, Serra E. Raising Spanish children with an antisocial tendency: do we know what the optimal parenting style is? J Interpers Violence. 2021;36(13–14):6117–6144. doi:10.1177/0886260518818426

42. Garcia OF, Serra E. Raising children with poor school performance: parenting styles and short- and long-term consequences for adolescent and adult development. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(7):1089. doi:10.3390/ijerph16071089

43. Garcia OF, Serra E, Zacares JJ, Garcia F. Parenting styles and short- and long-term socialization outcomes: a study among Spanish adolescents and older adults. Psychosoc Interv. 2018;27(3):153–161. doi:10.5093/pi2018a21

44. Martinez I, Garcia F, Veiga F, Garcia OF, Rodrigues Y, Serra E. Parenting styles, internalization of values and self-esteem: a cross-cultural study in Spain, Portugal and Brazil. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(7):2370. doi:10.3390/ijerph17072370

45. Perez-Gramaje AF, Garcia OF, Reyes M, Serra E, Garcia F. Parenting styles and aggressive adolescents: relationships with self-esteem and personal maladjustment. Eur J Psychol Appl Legal Context. 2020;12(1):1–10. doi:10.5093/ejpalc2020a1

46. Queiroz P, Garcia OF, Garcia F, Zacares JJ, Camino C. Self and nature: parental socialization, self-esteem, and environmental values in Spanish adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(10):3732. doi:10.3390/ijerph17103732

47. Riquelme M, Garcia OF, Serra E. Psychosocial maladjustment in adolescence: parental socialization, self-esteem, and substance use. An Psicol. 2018;34(3):536–544. doi:10.6018/analesps.34.3.315201

48. Calafat A, Garcia F, Juan M, Becoña E, Fernández-Hermida JR. Which parenting style is more protective against adolescent substance use? Evidence within the European context. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;138:185–192. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.02.705

49. Gimenez-Serrano S, Alcaide M, Reyes M, Zacarés JJ, Celdrán M. Beyond parenting socialization years: the relationship between parenting dimensions and grandparenting functioning. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(8):4528. doi:10.3390/ijerph19084528

50. Martínez I, Garcia JF. Internalization of values and self-esteem among Brazilian teenagers from authoritative, indulgent, authoritarian, and neglectful homes. Adolescence. 2008;43(169):13–29.

51. Rosenberg M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press; 1965.

52. Garcia F, Martínez I, Balluerka N, Cruise E, Garcia OF, Serra E. Validation of the five-factor self-concept questionnaire AF5 in Brazil: testing factor structure and measurement invariance across language (Brazilian and Spanish), gender, and age. Front Psychol. 2018;9:2250. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02250

53. Marsh HW, Martin AJ. Academic self-concept and academic achievement: relations and causal ordering. Br J Educ Psychol. 2011;81(1):59–77. doi:10.1348/000709910X503501

54. Marsh HW, Shavelson RJ. Self concept: its multifaceted, hierarchical structure. Educ Psychol. 1985;20:107–123. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep2003_1

55. Fuentes MC, Garcia OF, Garcia F. Protective and risk factors for adolescent substance use in Spain: self-esteem and other indicators of personal well-being and ill-being. Sustainability. 2020;12(15):5967. doi:10.3390/su12155962

56. Chen F, Garcia OF, Fuentes MC, Garcia-Ros R, Garcia F. Self-concept in China: validation of the Chinese version of the Five-Factor Self-Concept (AF5) questionnaire. Symmetry-Basel. 2020;12(798):1–13. doi:10.3390/sym12050798

57. Shavelson RJ, Hubner JJ, Stanton GC. Self-concept: validation of construct interpretations. Rev Educ Res. 1976;46:407–441. doi:10.3102/00346543046003407

58. Leung KC, Marsh HW, Craven RG, Abduljabbar AS. Measurement invariance of the Self-Description Questionnaire II in a Chinese sample. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2016;32(2):128–139. doi:10.1027/1015-5759/a000242

59. Veiga FH, Garcia F, Reeve J, Wentzel K, Garcia OF. When adolescents with high self-concept lose their engagement in school. Rev Psicodidact. 2015;20(2):305–320. doi:10.1387/RevPsicodidact.12671

60. Calafat A, Juan M, Becoña E, García O. Parenting style and adolescent substance use: evidence in the European context. In: Garcia F, editor. Parenting: Cultural Influences and Impact on Childhood Health and Well-Being. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers, Inc; 2015:163–175.

61. Lee J. Universals and specifics of math self-concept, math self-efficacy, and math anxiety across 41 PISA 2003 participating countries. Learn Individ Differ. 2009;19(3):355–365. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2008.10.009

62. Kelley HH. The processes of causal attribution. Am Psychol. 1973;28(2):107–128. doi:10.1037/h0034225

63. Preckel F, Niepel C, Schneider M, Brunner M. Self-concept in adolescence: a longitudinal study on reciprocal effects of self-perceptions in academic and social domains. J Adolesc. 2013;36(6):1165–1175. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.09.001

64. Glick P, Fiske ST. An ambivalent alliance - Hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality. Am Psychol. 2001;56(2):109–118. doi:10.1037//0003-066X.56.2.109

65. Glick P, Fiske ST. The ambivalent sexism inventory: differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;70(3):491–512. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.70.3.491

66. Rudman LA, Glick P. Prescriptive gender stereotypes and backlash toward agentic women. J Soc Iss. 2001;57(4):743–762. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00239

67. Lila M, Gracia E, Garcia F. Ambivalent sexism, empathy and law enforcement attitudes towards partner violence against women among male police officers. Psychol Crime Law. 2013;19(10):907–919. doi:10.1080/1068316X.2012.719619

68. Lila M, Gracia E, Garcia F. Actitudes de la policía ante la intervención en casos de violencia contra la mujer en las relaciones de pareja: influencia del sexismo y la empatía [Police attitudes toward intervention in cases of partner violence against women: the influence of sexism and empathy]. Rev Psicol Soc. 2010;25(3):313–323.

69. Glick P, Fiske ST, Mladinic A, et al. Beyond prejudice as simple antipathy: hostile and benevolent sexism across cultures. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;79(5):763–775. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.763

70. Grusec JE, Goodnow JJ. Impact of parental discipline methods on the child's internalization of values: a reconceptualization of current points-of-view. Dev Psychol. 1994;30:4–19. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.30.1.4

71. Baumrind D. Rejoinder to Lewis reinterpretation of parental firm control effects: are authoritative families really harmonious? Psychol Bull. 1983;94:132–142. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.94.1.132

72. Martínez I, Garcia JF. Impact of parenting styles on adolescents’ self-esteem and internalization of values in Spain. Span J Psychol. 2007;10:338–348. doi:10.1017/S1138741600006600

73. Schwartz SH, Melech G, Lehmann A, Burgess S, Harris M, Owens V. Extending the cross-cultural validity of the theory of basic human values with a different method of measurement. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2001;32:519–542. doi:10.1177/0022022101032005001

74. Schwartz SH, Sagiv L. Identifying culture-specifics in the content and structure of values. J Cross Cult Psychol. 1995;26:92–116. doi:10.1177/0022022195261007

75. Schwartz SH, Bardi A. Value hierarchies across cultures: taking a similarities perspective. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2001;32:268–290. doi:10.1177/0022022101032003002

76. Silverberg SB, Steinberg L. Adolescent autonomy, parent–adolescent conflict, and parental well-being. J Youth Adolesc. 1987;16:293–312. doi:10.1007/BF02139096

77. Kaufmann D, Gesten E, Lucia RCS, Salcedo O, Rendina-Gobioff G, Gadd R. The relationship between parenting style and children’s adjustment: the parents’ perspective. J Child Fam Stud. 2000;9(2):231–245. doi:10.1023/A:1009475122883

78. Dolgin KG, Berndt N. Adolescents’ perceptions of their parents’ disclosure to them. J Adolesc. 1997;20:431–441. doi:10.1006/jado.1997.0098

79. Amato PR, Afifi TD. Feeling caught between parents: adult children’s relations with parents and subjective well-being. J Marriage Fam. 2006;68(1):222–235. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00243.x

80. Grundy E, Henretta JC. Between elderly parents and adult children a new look at the intergenerational care provided by the “sandwich generation”. Ageing Soc. 2006;26:707–722. doi:10.1017/S0144686X06004934

81. Lawton L, Silverstein M, Bengtson V. Affection, social contact, and geographic distance between adult children and their parents. J Marriage Fam. 1994;56(1):57–68. doi:10.2307/352701

82. Mancini JA, Blieszner R. Aging parents and adult children - research themes in intergenerational relations. J Marriage Fam. 1989;51(2):275–290. doi:10.2307/352492

83. Rothrauff TC, Cooney TM, An JS. Remembered parenting styles and adjustment in middle and late adulthood. J Gerontol Ser B. 2009;64(1):137–146. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbn008

84. Arnett J. Adolescent storm and stress, reconsidered. Am Psychol. 1999;54(5):317–326. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.54.5.317

85. Steinberg L, Morris A. Adolescent development. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:83–110. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.83

86. Sawyer SM, Azzopardi PS, Wickremarathne D, Patton GC. The age of adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2018;2(3):223–228. doi:10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30022-1

87. Amato PR, Fowler F. Parenting practices, child adjustment, and family diversity. J Marriage Fam. 2002;64(3):703–716. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00703.x

88. Del Milagro Aymerich M, Musitu G, Palmero F. Family socialisation styles and hostility in the adolescent population. Sustainability. 2018;10(9):2962. doi:10.3390/su10092962

89. Palacios I, Garcia OF, Alcaide M, Garcia F. Positive parenting style and positive health beyond the authoritative: self, universalism values, and protection against emotional vulnerability from Spanish adolescents and adult children. Front Psychol. 2022;13. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1066282

90. Gimenez-Serrano S, Garcia F, Garcia OF. Parenting styles and its relations with personal and social adjustment beyond adolescence: is the current evidence enough? Eur J Dev Psychol. 2022;19(5):749–769. doi:10.1080/17405629.2021.1952863

91. Gracia E, Garcia F, Lila M. Public responses to intimate partner violence against women: the influence of perceived severity and personal responsibility. Span J Psychol. 2009;12:648–656. doi:10.1017/S1138741600002018

92. Climent-Galarza S, Alcaide M, Garcia OF, Chen F, Garcia F. Parental socialization, delinquency during adolescence and adjustment in adolescents and adult children. Behav Sci (Basel). 2022;12(11). doi:10.3390/bs12110448

93. Rohner RP. Parental acceptance-rejection/control questionnaire (PARQ/Control). In: Rohner RP, Khaleque A, editors. Handbook for the Study of Parental Acceptance and Rejection. Storrs, CT: Rohner Research Publications; 2005:137–186.

94. Khaleque A, Rohner RP. Perceived parental acceptance-rejection and psychological adjustment: a meta-analysis of cross-cultural and intracultural studies. J Marriage Fam. 2002;64:54–64. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00054.x

95. Arrindell WA, Sanavio E, Aguilar G, et al. The development of a short form of the EMBU: its appraisal with students in Greece, Guatemala, Hungary and Italy. Pers Individ Differ. 1999;27(4):613–628. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00192-5

96. Buri JR. Parental Authority Questionnaire. J Pers Assess. 1991;57(1):110–119. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa5701_13

97. Rohner RP, Khaleque A. Reliability and validity of the parental control scale: a meta-analysis of cross-cultural and intracultural studies. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2003;34(6):643–649. doi:10.1177/0022022103255650

98. Khaleque A, Rohner RP. Reliability of measures assessing the pancultural association between perceived parental acceptance-rejection and psychological adjustment: a meta-analysis of cross-cultural and intracultural studies. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2002;33(1):87–99. doi:10.1177/0022022102033001006

99. Garcia F, Fernández-Doménech L, Veiga FH, Bono R, Serra E, Musitu G. Parenting styles and parenting practices: analyzing current relationships in the Spanish context. In: Garcia F, editor. Parenting: Cultural Influences and Impact on Childhood Health and Well-Being. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers, Inc; 2015:17–31.

100. Garcia F, Musitu G. AF5: Self-Concept Form 5. Vol. 265. Madrid, Spain: TEA editions; 1999.

101. Garcia JF, Musitu G, Riquelme E, Riquelme P. A confirmatory factor analysis of the “Autoconcepto Forma 5” questionnaire in young adults from Spain and Chile. Span J Psychol. 2011;14:648–658. doi:10.5209/rev_SJOP.2011.v14.n2.13

102. Fuentes MC, Garcia F, Gracia E, Lila M. Self-concept and drug use in adolescence. Adicciones. 2011;23(3):237–248. doi:10.20882/adicciones.148

103. Murgui S, García C, García A, Garcia F. Self-concept in young dancers and non-practitioners: confirmatory factor analysis of the AF5 scale. Rev Psicol Deporte. 2012;21(2):263–269.

104. Tomás JM, Oliver A. Confirmatory factor analysis of a Spanish multidimensional scale of self-concept. Interam J Psychol. 2004;38(2):285–293.

105. Garcia JF, Musitu G, Veiga FH. Self-concept in adults from Spain and Portugal. Psicothema. 2006;18(3):551–556.

106. Garcia F, Gracia E, Zeleznova A. Validation of the English version of the five-factor self-concept questionnaire. Psicothema. 2013;25(4):549–555. doi:10.7334/psicothema2013.33

107. Raboteg-Saric Z, Sakic M. Relations of parenting styles and friendship quality to self-esteem, life satisfaction and happiness in adolescents. Appl Res Qual Life. 2014;9(3):749–765. doi:10.1007/s11482-013-9268-0

108. Schwartz SH, Bilsky W. Toward a universal psychological structure of human-values. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;53:550–562. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.53.3.550

109. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41(4):1149–1160. doi:10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

110. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39(2):175–191. doi:10.3758/BF03193146

111. Pérez JFG, Navarro DF, Llobell JP. Statistical power of Solomon design. Psicothema. 1999;11(2):431–436.

112. Garcia JF, Pascual J, Frias MD, Van Krunckelsven D, Murgui S. Design and power analysis: n and confidence intervals of means. Psicothema. 2008;20(4):933–938.

113. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences.

114. Aquilino W, Supple A. Long-term effects of parenting practices during adolescence on well-being outcomes in young adulthood. J Fam Issues. 2001;22(3):289–308. doi:10.1177/019251301022003002

115. Candel O. The link between parenting behaviors and emerging adults’ relationship outcomes: the mediating role of relational entitlement. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(2):828. doi:10.3390/ijerph19020828

116. Sanders M, Hoang NT, Hodges J, et al. Predictors of change in stepping stones triple interventions: the relationship between parental adjustment, parenting behaviors and child outcomes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(20):13200. doi:10.3390/ijerph192013200

117. Fuentes MC, Garcia OF, Alcaide M, Garcia-Ros R, Garcia F. Analyzing when parental warmth but without parental strictness leads to more adolescent empathy and self-concept: evidence from Spanish homes. Front Psychol. 2022;13. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1060821

118. Alcaide M, Garcia OF, Queiroz P, Garcia F. Adjustment and maladjustment to later life: evidence about early experiences in the family. Front Psychol. 2023;14. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1059458

119. Minuchin P. Families and individual development - provocations from the field of family-therapy. Child Dev. 1985;56(2):289–302. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1985.tb00106.x

120. Infurna FJ, Gerstorf D, Lachman ME. Midlife in the 2020s: opportunities and challenges. Am Psychol. 2020;75(4):470–485. doi:10.1037/amp0000591

121. Lamers SMA, Bohlmeijer ET, Korte J, Westerhof GJ. The efficacy of life-review as online-guided self-help for adults: a randomized trial. J Gerontol Ser B. 2015;70(1):24–34. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbu030

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.