Back to Journals » Journal of Pain Research » Volume 14

Pain Management – A Decade’s Perspective of a New Subspecialty

Authors Hochberg U, Sharon H , Bahir I, Brill S

Received 3 February 2021

Accepted for publication 15 March 2021

Published 9 April 2021 Volume 2021:14 Pages 923—930

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S303815

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Robert Twillman

Uri Hochberg,1,2 Haggai Sharon,1– 3 Iris Bahir,1,2 Silviu Brill1,2

1Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, Institute of Pain Medicine, Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Tel Aviv, Israel; 2Sackler School of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel; 3Sagol Brain Institute, Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Tel Aviv, Israel

Correspondence: Uri Hochberg

Institute of Pain Medicine, Division of Anesthesiology, Tel Aviv Medical Center, 6 Weizmann Street, Tel Aviv, Israel

Tel +972 3-6974477

Email [email protected]

Objective: Pain management is increasingly recognized as a formal medical subspecialty worldwide. Israel was among the first to offer a board-certified subspecialty, formalized by the Israeli Medical Association in 2010 which is open to all clinicians with a state-recognized specialization. This paper aims at evaluating the current program across several quality control measures.

Design: A survey among pain medicine specialists who graduated from the Israeli Pain Management subspecialty.

Methods: All 43 graduates of the program were sent a web-based questionnaire, each related to a different time in the participants’ residency period – prior to, during and after training.

Results: Forty-one physicians responded to the survey (95% response rate). The most common primary specialty was Anesthesiology (44%), followed by Family Medicine (22%). One-third of the respondents applied to the program over five years after completing their initial residency. Two-thirds reported that they acquired all or most of the professional tools required by a pain specialist. Insufficient training was mentioned regarding addiction management (71%), special population needs (54%) and interventional treatment (37%). A high proportion (82%) responded that the examination contributed to their training and almost all perceived their period of subspecialty as having a positive value in their personal development. Two-thirds of respondents had not yet actively engaged beyond the clinical aspect with other entities responsible for formulating guidelines and other strategic decision-making.

Conclusion: We hope the findings of this first-of-a-kind survey will encourage other medical authorities to construct formal training in pain medicine and enable this discipline to further evolve.

Keywords: chronic pain, medical education, curriculum, pain management, pain training programs

Plain Language Summary

The World Health Organization recognizes chronic pain as a major social, medical, and economic problem so Pain Management is increasingly being recognized as a formal medical subspecialty. This study is an attempt to evaluate the participants’ perspectives on the current Israeli subspecialty program in pain medicine across several quality control measures via a-first-of-a-kind survey taken by all graduates over a 10-year period.

A number of interesting insights and gaps were identified regarding the Israeli sub-specialty including:

- The majority of physicians in this study feel that they received most of the professional tools they needed during the specialty training, however a large proportion reported a lack of sufficient training with respect to special populations, mental care and addiction.

- Most physicians reported job satisfaction and yet a large proportion believe that the discipline of pain medicine is highly prone to burnout.

- A small percentage of respondents (20%) are currently involved in research and two-thirds of respondents had not yet actively engaged beyond the clinical aspect in the broader medical ecosystem, pointing to the fact that the current focus is mostly clinical.

We hope that the insights and gaps we identified in this first-of-a-kind survey will be addressed in future pain medicine training locally in Israel. Globally, we hope the Israeli approach will encourage other national medical authorities to conduct formal training and establishment of a board-certified medical subspecialty in Pain Management, enabling this discipline to further evolve.

Introduction

Pain management is increasingly being recognized and conceptualized as a formal medical subspecialty, with several factors pushing this process forward. The global burden of disease study in 2016 suggested that pain-related diseases are the leading cause of disability and disease burden globally.1 This field is rapidly growing due to recent advances in our understanding of the neuropathophysiological processes underlying chronic pain. Therefore, the theoretical and translational basis of clinical pain management requires increasing study and specialization. Chronic pain patients often present with multiple comorbidities, which necessitate a multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis and management. This, in turn, requires pain practitioners to have a large and unique set of skills varying from psychology-based interventions to rehabilitative techniques, and from complex pharmacotherapy (including psychoactive and regulated substances) to interventional therapies. Currently, there are substantial deficiencies in this field, both within medical school curricula and in residency and continued physician training.2, Moreover, a structured approach to specifically train physicians in advanced pain management is unfortunately not the norm, with few countries having a formal board specialty.

The European Pain Federation (EFIC) currently offers a few options for those physicians interested in pain education: from short 5-day “Pain Schools” and 10-week fellowship programs to the “European Diploma in Pain Medicine” (EDPM). While these options are important and welcome additions to global pain training, they do not constitute a comprehensive advanced training program.

Currently there are full-time pain fellowship programs, usually 12 months long, in the UK, North America and Australia. These are intended to extend training after completing formal specialty education and typically only accept physicians with a primary specialty in Anesthesiology. A small proportion of these programs also admit practitioners from Neurology, Psychiatry, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, and Neurosurgery.

A recent paper by Belgrade, discusses the current status, flaws and needs of such fellowship in the US; stating that 90% of accredited pain fellowships being core anesthesia programs, a factor that pushes trainees in the direction of procedural based practices.3 In order to attract a broader group of residents to the field and ensure comprehensive training, Belgrade proposes a two-year dual track pain specialty, covering both the interventional and medical pain management aspects of the specialty.

In Israel, an official, board-certified subspecialty in pain management (dubbed “Pain Relief Medicine”) was recognized by the Israeli Medical Association as recently as 2010. It is open to all clinicians with a previous state-recognized specialization. The current structure of training consists of 27 months in a recognized Chronic Pain Management unit, of which three months are spent in the Anesthesia Department and three further months in the Neurology Department. In some cases, the subspecialty can be taken on a part-time basis, over a period of 56 months. At the end the resident must pass written and oral examinations in order to obtain the title of “Specialist.” The written exam is composed of 100 multiple-choice questions based on the curriculum books and recent prominent peer-reviewed papers covering all the aspects of pain management. In the oral section, the resident is presented with a series of cases and is asked to evaluate and discuss them, similarly to the “objective structured clinical examination” (OSCE). The first exam was given in 2013; to date, 43 doctors have completed their training requirements.

This paper summarizes the findings of a survey we conducted among pain medicine specialists who graduated from the Israeli Pain Management subspecialty program. It is the first report of its kind analyzing in depth the pain subspecialty in an attempt to evaluate the current program across several quality control measures.

Methods

In November and December 2019, all 43 registered and active board-certified Israeli pain physicians who had taken the necessary training and exams up to that time were invited by email to complete a structured web-based survey using SurveyMonkey®, an internationally established and accepted tool for conducting surveys. It included open- and closed-ended questions, each related to a different time in the participants’ training period – prior to, during and after training. The survey was typically completed in 10–12 minutes. The first part of the survey followed their demographics and professional characteristics. The second part of the survey focused on the resident’s opinions regarding the academic content and quality of the subspecialty. The last part referred to post-training work as a graduate of the pain medicine program and a recognized specialist. Descriptive statistics were performed using Statistica 6 (Stat Soft. Inc.) and SPSS 21.0 software (SPSS Inc.) and results were described as percentage responses of the total study cohort.

The institutional review board (IRB) of the Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center (provided by the Chairman of the Helsinki Committee, within the Division of Research and Development) provided a waiver for the Helsinki medical ethics declaration based upon sections 20 and 23 of the Israeli Health Ministry guidelines (ie it was a web-based study targeting a healthy population, with no questions regarding the individual’s personal medical condition, no direct measurement of biological properties, and no medical interventions; 2) responses were completely anonymized, and no personal data regarding the responders were collected in any database). The participants of the study provided their implicit consent to participate in the study by filling out the online questionnaire.

Results

Demographics and Professional Characteristics (See Table 1)

Forty-one chronic pain residents participated in the current survey (95% response rate), of which forty responded to all questions and one respondent did not respond to 5 of the overall 28 questions. Fifty-eight percent were men and 84% were over 40 years old (66% of them younger than 50 years old). The most common primary specialty was Anesthesiology (44%) and the second most common was Family Medicine (22%). Thirty-seven percent of the responders joined a chronic pain subspecialty less than a year after their basic subspecialty ended, and 29% did so in the two to five years thereafter. The main reason for choosing chronic pain subspecialty was clinical interest (90%); however, half of the responders mentioned change of their workplace as an additional motivation.

|

Table 1 Demographics and Professional Characteristics |

Trainees’ Opinion on Various Aspects of Their Chronic Pain Subspecialty (See Figures 1–3)

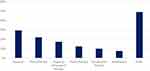

Most of the participants (83%) chose a full-time subspecialty and 66% of them reported that they acquired all or most of the skills needed for a pain specialist. Thirty-five percent replied that they received only part (35%), or only a small portion (10%), of what they deem is required. When asked about specific fields of pain management, insufficient training was mentioned in relation to managing addiction (71%), special population needs (54%), social aspects of chronic pain (42%), emotional/mental treatment (39%), and interventional treatment (37%). Nevertheless, 80% of the responders replied that the subspecialty contributed to their personal development. In addition, 83% of the residents felt that the final written exam contributed to their training. Finally, many of the residents acquired further additional training in other methods for pain management, such as hypnosis (31%), physiotherapy (24%), and behavioral-cognitive therapy (18%).

|

Figure 1 Residents’ opinion on skills acquired in various fields. |

|

Figure 2 Additional training received. |

|

Figure 3 Insufficient training fields. |

Post-Subspecialty Characteristics (See Figures 4 and 5)

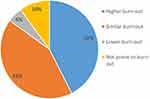

All trainees successfully passed the final exam and began working as pain physicians following the completion of the training. Sixty-three percent of the responders continued working in their basic specialization field concurrently. In terms of scientific contributions to pain research, 20% of the residents published scientific papers in the two years that preceded the survey; 45% participated in pain-related conferences, as lecturers or as workshop organizers; 45% served on institutional pain management committees; and 35% established new pain management public services. When asked about their future as pain specialists, 75% agreed with the statement: “I’ll work as a pain specialist for many years.” Based on their recent experience as new pain specialists, around half (43%) of the responders think that working as a pain specialist will lead to more “burnout” over time compared to other specialization fields, while the same amount think it is similar. Despite the general expectation of future burnout, sixty-three percent reported that they were currently completely satisfied with their work as pain specialists and 28% reported partial satisfaction.

|

Figure 4 Contribution to the field of pain medicine. |

|

Figure 5 Prone to burn-out. |

Discussion

The World Health Organization recognizes chronic pain as a major social, medical, and economic problem so Pain Management is increasingly being recognized as a formal medical subspecialty. In our view, a “new” medical profession should offer new tools of clinical and academic value. A physician undertaking a subspecialty is a potential future professional leader and should be trained accordingly. This study is an attempt to evaluate the current subspecialty program in pain medicine across several quality control measures.

Historically, both in Israel and worldwide, the field of pain medicine grew out of the field of clinical anesthesia. Accordingly, it is not surprising that the base specialty of 43% of respondents was Anesthesia. The second most common clinical specialty in our survey was Family Practice/Primary Care. We find this intriguing, as those two disciplines in many respects represent two opposite poles, in terms of patient-physician interaction and length of relationship. The fact that doctors from both ends of this spectrum were attracted to pain medicine illustrates the complexity of dealing with chronic pain, a syndrome that has no “magic bullet” solution and requires a combination of tools and approaches. It is therefore not surprising that in the United States, where there has been a clinical program for chronic pain management for decades, physicians specializing in pain medicine come from a wide range of clinical professions, including Anesthesia, Orthopedics, Neurosurgery, Neurology, Psychiatry and Rehabilitation. Of the 43 board-certified sub-specialists, there is only one pediatrician which we believe is a substantial under-representation of current needs. Indeed, recent studies point towards a great focus and improvement in pain management in the pediatric population.4,5

One-third of the respondents applied for the subspecialty in pain medicine more than five years after completing their basic residency. This figure may indicate a need to achieve professional “maturity,” self-esteem and stature to engage with this complex population of patients, but may well also originate in the lack of formal specialization available in the past. In this context, although the majority turned to this practice out of clinical interest, about half of the respondents also indicated a desire to change their everyday working environment. It is worth noting that almost all respondents perceived their period of subspecialty as having a positive value in their personal development as human beings. In the future, it will be interesting to try to understand the source of this sentiment, as it may also help to deal with the problem of burnout.

Burnout is commonplace amongst US physicians, at substantially higher rates than other workers. Studies in the US suggest that at least half of physicians experience professional burnout, which is characterized by fatigue, cynicism, and a reduction in work effort.6,7 Although 40% of the respondents believed that the discipline of pain medicine is highly prone to burnout, half of those applying for the subspecialty did so as a means of changing their work environment, and almost all of them (88%) reported job satisfaction; of the latter percentage, 62.5% reported great satisfaction and three-quarters of the respondents (75%) expect to continue in this field for many years to come. As a follow up, it would be interesting to monitor whether there is a change in sentiment over time.

Two-thirds of the experts feel they received most of the professional tools they needed during the specialty training. Nonetheless, various questions arise on closer observation of the results. Over 50% of responders reported a feeling that they did not receive enough training to address the needs of special and weakened populations; 40% reported a lack of adequate training for emotional/mental care; and, more importantly, 70% of the respondents claimed they did not receive training for one of the most pressing problems of our time: addiction (generally and specifically related to patients with a psychiatric comorbidity). The stigmas around chronic pain, opioids, and addiction are barriers to effective care and patient health outcomes,2 and hence we believe additional emphasis should be placed on addressing mental care and the fundamentals of addiction management. A total of 24 (58%) of the respondents reported that, in addition to the specialization, they gained knowledge in other fields relevant to pain management before, during and/or after specialization. The supplemental fields reported by the respondents are “soft” and non-invasive, and help to inculcate a broader and holistic approach to the pain experience. Remarkably, nearly one-third (31.6%) of all survey respondents reported training in hypnosis, a familiar therapeutic approach often offered by psychology, and nearly one-fifth (19.5%) reported studying psychotherapy or CBT.

We find the meager rate of those engaged in the academic side of pain medicine, research and teaching, to be particularly disturbing. Only 20% of these young experts reported that they are involved in research; in our opinion, is an insufficient percentage. It should be noted that, in primary clinical specialties in Israel, research work is a mandatory requirement for completing the specialization and obtaining a “Specialist” degree. We think such a pre-requisite should also be considered for this subspecialty, as research is a driving force for progress and will also establish and sustain a faculty who will provide the future educational and training programs.

We believe that a well-trained pain physician can be valuable in shaping policies, regulations and guidelines for the efficient performance of the healthcare system. While over half of the responders initiated or opened a new clinical service, two-thirds of respondents had not yet actively engaged beyond the clinical aspect with other entities responsible for formulating guidelines and other strategic decision-making. So far it seems that the contribution from pain specialists has been mostly clinical. There is a significant lack of representation in the broader medical ecosystem, possibly due to the recent establishment of this subspecialty.

Two-thirds of the experts feel they received most of the professional tools they needed during the specialty training. Nonetheless, various questions arise on closer observation of the results. Over 50% of responders reported a feeling that they did not receive enough training to address the needs of special and weakened populations; 40% reported a lack of adequate training for emotional/mental care; and, more importantly, 70% of the respondents claimed they did not receive training for one of the most pressing problems of our time: addiction (generally and specifically related to patients with a psychiatric comorbidity). The stigmas around chronic pain, opioids, and addiction are barriers to effective care and patient health outcomes,2 and hence we believe additional emphasis should be placed on addressing mental care and the fundamentals of addiction management.

Passing a final examination at the end of the subspecialty is a requirement in order to receive the title of “Specialist” in Israel. Taking exams is considered stressful and constitutes a significant burden, both in terms of time and resources. Although all residents were experienced physicians who applied for this specialization at a later stage of their careers, a very high proportion (82%) responded that the examination, despite the associated stress, contributed to their training. This finding reinforces the current requirement for a final examination and should be considered an integral part of the framework of chronic pain specialization in other countries.

This survey was aimed at evaluating the residents’ training time and subsequent professional evolution, a multifaceted and complex phenomenon. It is the first of its kind conducted in Israel, and therefore there are no previous data for comparison.

A recent position taken on the current state of the one-year fellowship available in the US is that it “may not be sufficient for many residents given the diversity and complexity of pain conditions and the breadth and depth of knowledge and skills required”.8 This position is reinforced by Belgrade who proposes a two-year fellowship and emphasizes the importance of training pain specialists in the most comprehensive way as possible.3 In his view, this will result in more patient centered pain management practices, better outcomes from procedure-based treatments, greater involvement with complex patients and a higher focus on research in this field.

Although our training program is 27 months, given the vast expertise required to reach “professional competence,” it is not surprising to find gaps in the training. Epstein and Hundert provide a useful definition of “professional competence” as the habitual and judicious use of communication, knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning, emotions, values, and reflection in daily practice for the benefit of the individual and community being served.9 As the concept of competence is complex and multileveled, others argue that it should also require situational awareness, metacognition, attentive automaticity, and shared or distributed cognition in collaborative work.10 Being “competent” is not the end per se, and the concept of competence is not static: skills drift or become obsolete, necessitating further training in order to maintain basic competence and develop higher levels of proficiency. As such, it would be interesting to conduct a similar survey among the same group of responders in the future, asking them to evaluate their change in views and perspectives.

The main strength of the survey is the high rate of response. We attribute this to the small population size, as well as to the authors’ personal and direct connections, which may have encouraged their willingness to cooperate when requested.

Key research questions emerge and remain to be answered in the future:

- Which components of the formal pain management subspecialty best correlate with graduates’ sense of personal development as found in the current study?

- Do subspecialty programs that require a mandatory research period result in greater involvement of graduates in the medical ecosystem following their certification?

- Which components of the formal pain management subspecialty best correlate with graduates’ sense of professional clinical competence?

Conclusion

In today’s medical environment, the pain physician is entrusted to provide better patient care, as well as a source of knowledge both for the public and policymakers. We hope that the gaps we identified in this first of a kind survey will be addressed in future pain medicine training locally in Israel. Globally, we hope the Israeli approach will encourage other national medical authorities to conduct formal training and establishment of a board-certified medical subspecialty in Pain Management, enabling this discipline to further evolve.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Ms. Vivian Serfaty for proofreading this paper.

Funding

The authors have no sources of funding to declare for this manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest for this work.

References

1. Vos T, Allen C, Arora M. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1211–1259.

2. Cheng J. Pain education, a strategic priority of the AAPM. Pain Med. 2019;20(3):428–429. doi:10.1093/pm/pny302

3. Belgrade M, Belgrade A. Why do physicians choose pain as a specialty? Pain Med. 2020;pnaa283. 10.1093/pm/pnaa283.

4. Milani GP, Benini F, Dell’Era L, et al. PIERRE GROUP STUDY. Acute pain management: acetaminophen and ibuprofen are often under-dosed. Eur J Pediatr. 2017;176(7):979–982. doi:10.1007/s00431-017-2944-6

5. Benini F, Castagno E, Urbino AF, Fossali E, Mancusi RL, Milani GP. Pain management in children has significantly improved in the Italian emergency departments. Acta Paediatr. 2020;109(7):1445–1449. doi:10.1111/apa.15137.

6. Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377–1385. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199

7. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129–146. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004

8. Cheng J. State of the art, challenges, and opportunities for pain medicine. Pain Med. 2018;19(6):1109–1111. doi:10.1093/pm/pny073

9. Epstein RM, Hundert EM. Defining and assessing professional competence. JAMA. 2002;287(2):226–235. doi:10.1001/jama.287.2.226

10. Leung AS, Epstein RM, Moulton CAE. The competent mind: beyond cognition. In: Hodges BD, Lingard L, editors. The Question of Competence: Reconsidering Medical Education in the 21st Century. New York: Cornell University Press; 2012:155–176.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.