Back to Journals » Risk Management and Healthcare Policy » Volume 16

One Health Systems Assessments for Sustainable Capacity Strengthening to Control Priority Zoonotic Diseases Within and Between Countries

Authors Standley CJ , Fogarty AS , Miller LN, Sorrell EM

Received 25 July 2023

Accepted for publication 30 October 2023

Published 21 November 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 2497—2504

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S428398

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Jongwha Chang

Claire J Standley,1,2,* Alanna S Fogarty,1 Lauren N Miller,1 Erin M Sorrell3,*

1Center for Global Health Science and Security, Georgetown University, Washington, DC, USA; 2Heidelberg Institute of Global Health, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany; 3Center for Health Security, Johns Hopkins University; Department of Environmental Health and Engineering, Bloomberg School of Public Health & Whiting School of Engineering, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Correspondence: Claire J Standley, Center for Global Health Science and Security, Georgetown University, 3900 Reservoir RoadNW, Washington, DC, 20007, USA, Tel +1 202 290 0451, Fax + 1 202-687-1800, Email [email protected]

Abstract: One Health is increasingly recognized as an important approach for health systems, particularly with respect to strengthening prevention, detection and response to zoonotic and other emerging disease threats. While many global health security frameworks reference the importance of One Health, there are fewer existing methodologies, tools, and resources for supporting countries and other regional or sub-national authorities in systematically assessing their One Health capabilities. We describe here two methodologies, One Health Systems Assessment for Priority Zoonoses (OHSAPZ) and One Health Transboundary Assessment for Priority Zoonoses (OHTAPZ), which have been developed to assist with creating consensus lists of priority zoonotic diseases for cross-sectoral consideration; identification of current strengths and gaps in One Health communication and coordination between sectors (and, in the case of OHTAPZ, between countries); and the development and dissemination of prioritized recommendations for future capacity strengthening. Implemented to date in seven diverse countries in Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean regions, these tools provide a modular, flexible and easily adaptable approach to One Health systems assessment that can support national capacity strengthening, regional epidemic preparedness, and compliance with international frameworks.

Keywords: intersectoral coordination, capabilities mapping, information sharing and risk communication, epidemic preparedness and response, transboundary zoonotic diseases, global health security

Introduction

Modern global health initiatives have adopted a One Health approach to assessing and building capacities for the prevention, detection, response and recovery to emerging infectious diseases, a majority of which are zoonotic in nature. The ultimate goal is the integration of systems for communication and coordination between human, animal and environmental health sectors. Zoonotic disease threats are complex, often multifactorial, and can encompass a variety of species as reservoir and/or intermediate hosts and may result in transboundary spread. Therefore, robust and progressive One Health prevention, mitigation and response strategies require concerted efforts that identify related networks and outline operational interdependencies between public health and all other relevant sectors.

Under the International Health Regulations (IHR), member states of the World Health Organization (WHO) are mandated to build and sustain capacities for detection, assessment, notification and response to public health threats, including zoonoses, with the potential for international spread.1 To assist compliance, WHO’s IHR Monitoring and Evaluation framework, including the Joint External Evaluation and State Party Self-Assessment Annual Reporting tools, use indicators to measure status of implementation for core capacity development both within national borders and at points of entry (PoE).2,3 One Health’s deliberate acknowledgement of interconnectedness aligns with the all-hazard approach to health risks and multisectoral coordination prescribed by the IHR and other global health security frameworks. In 2010, recognizing the importance of multisectoral engagement within the One Health approach, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH, formerly OIE), and WHO formalized their collaboration as the Tripartite.4 Two more strategic documents were released in 2017 and 2019 expanding scope to include areas like early warning, food safety and neglected tropical diseases5 and providing examples of best practices and country experiences.6 In 2021, the Tripartite expanded to the Quadripartite with the addition of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) as an equal partner, acknowledging the importance of the environmental dimension in a One Health approach. Together, the Quadripartite created the One Health Joint Plan of Action (2022–2026),7 to guide these organizations in working together on One Health efforts and support each organization’s respective Members, Member States, and State Parties build their One Health capacities.

While international frameworks and organizations call for advancing One Health approaches and methodologies, there is still a need to develop holistic One Health tools that capture interdisciplinary approaches for national outbreak preparedness and response strategies. These methodologies should include adaptable frameworks and metrics designed to accommodate dynamic environments with differing capabilities. In the past decade, several tools and resources have been developed for these purposes, including the One Health Zoonotic Disease Prioritization (OHZDP) Tool, developed by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;8 the University of Minnesota’s One Health Systems Mapping and Analysis Resource Toolkit (OH-SMART);9 the International Health Regulations-Performance of Veterinary Services (PVS) National Bridging Workshops (NBW), facilitated by WHO and WOAH;10 and the Operational Framework for Strengthening Human, Animal, and Environmental Public Health Systems at their Interface, developed by the World Bank.11 In 2022, the Tripartite launched the Surveillance and Information Sharing Operational Tool (SIS OT) to support nations in developing and sustaining mechanisms for multisectoral coordination on surveillance and information sharing for zoonotic diseases.12 The tool provides guidance and how to assess current capacities and provides links to a curated set of existing tools and resources that can help develop or improve that capacity.

These tools focus on different aspects of One Health efforts. OHZDP uses standardized qualitative and quantitative criteria to develop a multisectoral list of nationally relevant priority diseases, while OH-SMART focuses on assessing capacities for One Health communication and coordination, and to facilitate action-planning. OHZDP and OH-SMART have been successfully used together to combine disease prioritization and systems assessment.13 The NBWs focus more directly on identifying actions to strengthen multisectoral collaboration, and to advance sector-specific goals aligned with international frameworks such as IHR and PVS, and similarly the World Bank’s Operational Framework provides operational guidance to directly address the need for targeted investments that prevent, prepare, detect, respond to, and recover from disease pressures at the human-animal-environment interface. In this way, each of the tools brings different methodologies and approaches to the priority topic of improved One Health collaboration.

National One Health Systems Assessments

The One Health Systems Assessment for Priority Zoonoses (OHSAPZ) tool was initially developed in 2014 as an assessment and gap analysis methodology to map public health and veterinary systems used to detect and report priority zoonotic diseases, focusing on surveillance and laboratory networks. The timing of its development mirrored growing interest and investment in One Health tools, as noted in the previous section. Piloted in Jordan and Egypt in collaboration with each respective country’s Field Epidemiology Training Program, the methodology was subsequently also applied in Algeria and Iraq.14 In 2016, the methodology was refined to align more directly with the milestones and indicators under IHR’s revised Monitoring and Evaluation Framework, and also expanded to explicitly include the environmental health sector, for a more holistic One Health approach. The revised tool was piloted in Guinea in 2016, in collaboration with the Ministries of Health, Livestock, and Environment.15 In all cases, the authors worked closely with relevant stakeholders in the implementation of the methodology. Following these collaborations, we created the OHSAPZ manual which is freely available to download, and intended for future users to be able to implement independently if desired. In 2020–21 the tool was piloted for use in a remote setting, in partnership with Libya’s National Centre for Disease Control and National Centre for Animal Health, and again involving the authors as facilitators of the implementation process, in close coordination and collaboration with national stakeholders. The manual—including templates and related resources—were recently updated to better assist partner countries in using the OHSAPZ tool.16

Throughout its lifespan OHSAPZ has been a presented as a phased approach to identify and engage human, veterinary and environmental health sectors in the development of a consensus priority zoonotic diseases list; to examine the structures and mechanisms for communication and coordination between and within governmental sectors for the creation of systems map schematics; and provides a framework for analyzing strengths and weaknesses of existing intersectoral coordination in order to help identify gaps and develop targeted recommendations to strengthen One Health capacity and coordination. The ultimate goal is to help identify priorities and gaps that limit information-sharing for action focusing on zoonotic diseases seen as a priority by all implicated sectors.

The tool consists of a three-phase process of prioritization, systems mapping, and analysis and recommendations (Figure 1). Each phase has accompanying steps to consider and address before proceeding to the next phase. While this tool has been developed in collaboration with a number of stakeholders in low- and middle-income countries, it is amenable to adaptation for a variety of national perspectives, including approaches to prioritization at the subnational level or in times of insecurity/conflict. The prioritization phase (Phase I) begins with the identification and engagement of relevant stakeholders in One Health, from public health, agriculture/veterinary services, environmental health and wildlife (where applicable) and confirmation of their support for the process. These selected national stakeholders are then gathered (virtually or in person) to develop, through facilitated discussion, a consensus list of approximately five priority zoonotic diseases to undergo the OHSAPZ assessment. The selection of priority zoonoses is decided by a pre-determined list of selection criteria with no particular ranking that can be adapted for each country (ie, countries can add to or remove from the pre-selected list of criteria) depending on national priorities and considerations across the relevant stakeholders. The systems mapping phase (Phase II) uses the priority zoonotic diseases identified during the prioritization phase as case studies to address key aspects in national zoonotic disease management: prevention, surveillance and detection, national reporting, sample referral and testing, case management, outbreak investigation and response and international notification. The end result of this phase is the development of disease-specific systems maps that outline the existing processes for information sharing and coordination between sectors, at all levels of the health system. The analysis and recommendations phase (Phase III) uses the developed systems maps from Phase II to analyze the strengths and weaknesses of existing intersectoral coordination, and develop recommendations for actions to address the gaps.

|

Figure 1 The three phases of the OHSAPZ methodology. |

Transboundary One Health Systems Assessments

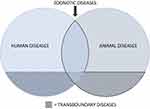

The need for consideration of zoonotic disease threats between borders and across regions led to further adaptation of OHSAPZ, in this case to assess, map and analyze transboundary zoonotic disease (TZD) threats, with a particular focus on ground crossing PoEs. The One Health Transboundary Assessment for Priority Zoonoses (OHTAPZ) tool takes the same phased approach as the OHSAPZ but explicitly recommends engagement of additional stakeholders (such as representatives from ministries with oversight over border crossings); supports consensus-building around a priority list of TZDs (Figure 2); and expands the systems map schematic stage to account for actions and protocols occurring at PoEs as well as with respect to informal or illegal crossing of humans or non-human animals.

|

Figure 2 Venn diagram outlining diseases to consider when determining priority transboundary zoonotic diseases. |

In addition to interim guidance provided during emergencies such as Ebola and COVID-19, WHO has published several technical frameworks and tools supporting core capacity assessment, surveillance integration, vector control and contingency planning for PoEs.17–21 All of WHO’s PoE guidance broadly acknowledges the diverse presence of authorities and activities at ground crossings, as well as the importance of cross-sectoral engagement and communication for public health risks; however, they do not fully address or assess multisectoral approaches to public health capacities. The Handbook for public health capacity-building at ground crossings and cross-border collaboration is the only PoE framework to explicitly include the terminology “One Health” and provides audiences comprehensive One Health approaches to and resources for surveillance, preparedness and response activities.21 The shortcomings of existing PoE resources undermines comprehensive, integrative capacity-building efforts and further hinders application of effective One Health operations for TZDs at PoEs.

The OHTAPZ tool is not intended to replace or duplicate PoE assessment tools. It was developed to be a starting point for countries to identify stakeholders, to engage authorities and networks that operate at formal PoEs to build better capacity for the prevention, detection, response, and bilateral coordination of a zoonotic event detected at ground crossings. It considers multidisciplinary networks within a PoE as well as the bilateral relationship across sectors. OHTAPZ provides a baseline that can inform additional public and veterinary health assessments at PoEs, in line with the JEE and other international frameworks, outlined above. The first edition tool and accompanying manual is under development. It was piloted in partnership with Libya and Tunisia in 2022 and is currently undergoing further evaluation through implementation with Iraq and Jordan. It has been designed to be used in sequence with OHSAPZ or as a stand-alone tool if a country has already conducted a national prioritization using one of the many tools available to them.

Lessons Learned and Opportunities

From experience in implementing OHSAPZ and OHTAPZ across numerous countries and regions, it is clear that there is a need for flexible, adaptable, and contextualizable tools to assess One Health capacities and make recommendations for systems strengthening. For example, the ability to implement these methodologies virtually, in-person, or through hybrid engagements proved to be an asset during the COVID-19 pandemic, and can contribute to cost savings with implementation as well. Furthermore, these methodologies can be applied at any administrative level (ie national, subnational or local). The modularity means that they can be used to complement other larger-scale One Health initiatives such as NBWs, but with sufficient flexibility in how diseases are selected (and notably without pre-determined weights or values to selection criteria) which assists in engaging all stakeholders and developing true consensus through facilitated discussion. Selection of approximately five priority diseases in each methodology provides ample opportunity to observe and document system-wide strengths and horizontal capabilities, which can be then easily highlighted under international framework evaluations such as in support of IHR, and more generally meeting core capacity requirements (Table 1). However, utilizing specific diseases also allows for identification of capacities that may have been developed through disease-specific or vertical programming, and which in turn provide leverage points and opportunities for expansion to other priority diseases.

|

Table 1 Alignment of OHSAPZ and OHTAPZ with Global Health Security Framework Indicators |

The disease schematic maps that result from each of the scenario-based discussions allow for a clear and intuitive visual analysis of existing networks for communication and coordination between sectors and levels of governance, as well as where gaps exist. Importantly, the creation of a schematic for each disease, as well as a consensus map, can highlight that capabilities do not need to be identical or even consistent between diseases to equate to strong overall systems; disease-specific requirements are certain to emerge. For example, diseases like cutaneous leishmaniasis and rabies may not require sophisticated laboratory diagnostic capability at every level of the health system, but prevention, surveillance, and case reporting should still be robust. Conversely, rapid detection and control of emerging and/or epidemic-prone diseases, such as Rift valley fever or Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, may rely more heavily on strong local laboratory diagnostics, leveraging rapid detection technologies such as ELISA or even point of care rapid diagnostic tests where available.

The process of developing and implementing these methodologies has also revealed challenges and lessons learned. While One Health has gained substantial traction and widespread use in recent years, it can remain challenging to identify and engage sectors that are less traditionally represented or involved in disease control. With the growing prominence of climate change, water scarcity, and food security as priority global issues, the mandate for environmental health authorities in many countries has grown in scope and scale, often now incorporating key aspects of zoonotic disease prevention and management, such as vector control, oversight of wildlife species, water quality and source management, food safety, and climate mitigation. However, responsibility for these issues can sometimes fall between diverse departments and agencies, or even across separate ministries, highlighting the importance of robust stakeholder mapping as an initial step in both the OHSAPZ and OHTAPZ methodologies.

As noted previously, there are several few One Health mapping and assessment tools available, which can make it confusing for stakeholders, or result in duplication. Efforts by the Quadripartite to collate and review tools, such as via the SIS OT, are an important step forward to mitigate these issues; in 2022, OHSAPZ was officially included in the SIS OT toolbox following piloting in Indonesia, Jordan, Uganda and Romania.

Conclusion

One Health is increasingly recognized as an important approach for preventing, detecting and responding to epidemic and emerging disease threats, as well as endemic health challenges. While numerous international frameworks exist to provide guidance for countries on what capacities are needed to achieve these aims, few are explicitly multisectoral. Moreover, these frameworks require complementary methodologies to assess and characterize existing capacities, and identify where opportunities lie for further system strengthening, across all relevant sectors. OHSAPZ and OHTAPZ provide flexible, modular and adaptable methodologies for achieving these aims, as demonstrated through their successful implementation across a number of countries to date. They are both designed such that they can either be used once, to establish a snapshot of capabilities and gaps, or periodically to measure progress as well as identify possible new gaps in communication and coordination within and among sectors. As countries recover from pandemics and emergency situations – whether due a natural disaster, civil conflict, change in governance - and reinvest in national priority zoonoses these methodologies provide a mechanism to compare pre-event and current capacities to identify targeted interventions for systems strengthening, both within and between countries.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the partners in Jordan, Egypt, Iraq, Algeria, Guinea, Libya and Tunisia who have contributed to the pilot testing and implementation of the OHSAPZ and OHTAPZ methodologies.

Author Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreed to submit to the current journal; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

We are grateful for funding support from US Department of State Biosecurity Engagement Program (CRDF_BEP-23036; S-ISNCT-14-CA-1011; and S-ISNCT-20-CA-0035); US Department of State, Nonproliferation and Disarmament Fund (SISNDF22GR009); and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1U19GH001264-01), which contributed to different phases of the development and use of these two methodologies.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. World Health Organization. International Health Regulations. World Health Organization; 2005.

2. World Health Organization. Joint External Evaluation Tool: International Health Regulations. World Health Organization; 2005.

3. World Health Organization. International Health Regulations (2005): State Party Self-Assessment Annual Reporting Tool. World Health Organization; 2005.

4. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, World Organisation for Animal Health, World Health Organization. The FAO-OIE-WHO Collaboration. A Tripartite Concept Note; 2010. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/the-fao-oie-who-collaboration.

5. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, World Organisation for Animal Health, World Health Organization. The tripartite’s commitment: providing multi-sectoral, collaborative leadership in addressing health challenges; 2017. Available from: https://www.woah.org/app/uploads/2021/03/tripartite-2017.pdf.

6. World Health Organization, Nations F and AO of the U, Health WO for A. Taking a Multisectoral, One Health Approach: A Tripartite Guide to Addressing Zoonotic Diseases in Countries. World Health Organization; 2019.

7. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. United Nations Environment Programme, World Health Organization, World Organisation for Animal Health. One Health Joint Plan Action. 2022;2022:86.

8. Rist CL, Arriola CS, Rubin C. Prioritizing zoonoses: a proposed one health tool for collaborative decision-making. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e109986. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0109986

9. University of Minnesota. The OH-SMART Framework | OH-SMART (One Health Systems Mapping and Analysis Resource Toolkit). Available from: https://oh-smart.umn.edu/oh-smart-framework.

10. Belot G, Caya F, Errecaborde KM, et al. IHR-PVS National Bridging Workshops, a tool to operationalize the collaboration between human and animal health while advancing sector-specific goals in countries. PLoS One. 2021;16(6):e0245312. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0245312

11. Berthe FCJ, Bouley T, Karesh WB, et al. One health: operational framework for strengthening human, animal, and environmental public health systems at their interface. World Bank Group; 2018. Available from: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/961101524657708673/One-health-operational-framework-for-strengthening-human-animal-and-environmental-public-health-systems-at-their-interface.

12. World Health Organization. Surveillance and Information Sharing Operational Tool: An Operational Tool of the Tripartite Zoonoses Guide. Food & Agriculture Org; 2022:61.

13. Varela K, Goryoka G, Suwandono A, et al. One health zoonotic disease prioritization and systems mapping: an integration of two one health tools. Zoonoses Public Health. 2023;70(2):146–159. doi:10.1111/zph.13015

14. Sorrell EM, El Azhari M, Maswdeh N, et al. Mapping of networks to detect priority zoonoses in Jordan. Front Public Health. 2015;3:219. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2015.00219

15. Standley CJ, Carlin EP, Sorrell EM, et al. Assessing health systems in Guinea for prevention and control of priority zoonotic diseases: a One Health approach. One Health. 2019;7:100093. doi:10.1016/j.onehlt.2019.100093

16. Fogarty AS, Standley CJ, Sorrell EM. One Health Systems Assessment for Priority Zoonoses (OHSAPZ). Georgetown University; Johns Hopkins University; 2023.

17. World Health Organization. WHO Interim Guidance for Ebola Event Management at Points of Entry. World Health Organization; 2014.

18. World Health Organization. Controlling the Spread of COVID-19 at Ground Crossings: Interim Guidance, 20 May 2020. World Health Organization; 2020.

19. Vector surveillance and control at ports, airports, and ground crossings. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241549592.

20. International health regulations (2005): a guide for public health emergency contingency planning at designated points of entry. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789290615668.

21. Handbook for public health capacity-building at ground crossings and cross-border collaboration. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240000292.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The

full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php

and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution

- Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted

without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly

attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.