Back to Journals » Nursing: Research and Reviews » Volume 7

Nurses’ perspectives on readiness of organizations for change: a comparative study

Authors Amarneh BH

Received 4 November 2016

Accepted for publication 8 March 2017

Published 6 April 2017 Volume 2017:7 Pages 37—44

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NRR.S126703

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Cindy Hudson

Basil Hameed Amarneh

Department of Psychiatric and Community Health Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid, Jordan

Purpose: The purpose of this study is to evaluate readiness for change perceived by nurses at Jordanian hospitals according to the hospital type and the gender of nurse.

Background: There are misconceptions about readiness for change, and only a few health care and nursing studies about organizational readiness for change have been conducted. Nurses’ perceptions of their organizations’ readiness for change are important; they help in introducing, managing, and maintaining the change.

Methods: Using a quantitative comparative research design and a validated survey, data were collected in 2010 from a convenience sample of 130 nurses from four government and three private hospitals with a response rate of 59%.

Results: There are some issues in Jordanian hospitals, which show that change has to be managed well. Nurses in government hospitals and female nurses perceived their hospitals to be more ready for change, compared with those in private hospitals and male nurses.

Conclusion: Government hospitals were more ready to change than private hospitals, particularly in supporting collaborative and multidisciplinary team approaches to patient care. More than male nurses, female nurses perceived that their organizations were ready to use or plan to use advanced practice nurses. One of the recommendations is a need for targeted intervention to improve readiness for change.

Keywords: readiness for change, organizations, hospitals, nurses, Jordan

Background

Readiness for change is associated with bringing about change, which is constant and inevitable. This means that change must be accurately managed1,2 and it should be preceded by readiness. However, there is a lack of clear criteria for assessing readiness for change. There have been few health care and nursing studies about readiness for change in organization.3–5 Readiness for change in organization is rarely described in the literature about organizational change.6 Readiness is viewed as the degree to which an organization is assessed as ready to experience change.1,4 Change does not suddenly happen and should be preceded by readiness for change.4,7

This current research proposes hypothetically that readiness for change in organizations affects resistance to change, which could be matched to many variables such as employees’ views about their organizations, gender of nurses, and types of hospitals.4,7,8 Although all health care team members should be involved in bringing the change and managing it, this study surveyed registered nurses (RNs) only. The reason is that the health care system in Jordan is centralized; this will lead to the assumption that several factors may negatively influence readiness for change in these organizations. Moreover, when females perceive their organizations to be ready for change, they will have better acceptance and management.9

Worldwide, many changes are influencing health care organizations, including those prompted by concerns about the quality and cost of patient care and the introduction of new technology in health care settings.5,10,11 The hospital industry has undergone major reorganization in response to financial constraints and as a result of massive and rapid technological changes, leading to a current focus on increasing effectiveness and efficiency through privatization and strategic alliances.2

How nurses perceive their organizational readiness for change is important, since they help in introducing, managing, and maintaining the change. Studying factors that may impact organizational readiness for change will shed light on strategies needed to manage change effectively.

The concept of “organizational readiness for change” has many definitions, including the ability of an organization to manage change4,11,12 and the motivation and character attributes of the program leaders as well as the staff, institution resources, in addition to the organization climates that conclude whether significant changes are expected to take place in any organization.13

Readiness for change in organizations has antecedents: young age, high levels of education and experience, personal growth, efficacy, training opportunities, adaptability, and the prevalence of certain organizational characteristics such as motivation, access to resources, the need for change, and the climates in organizations (including mission, unity, autonomy, communication, stress and change, leadership, power, and enthusiasm to adopt new methods), which will influence the readiness for change in organizations,4,5,7,11,14,15,16 and consequences: decreasing the resistance for change, resulting in the unfreezing of change into the system,7,11,17 and leading to positive outcomes such as increasing employee commitment to the organization.18,19

Readiness of organizations for change is linked to leadership capacity. Building leadership capacity means skillful involvement in the work of leadership20,21 and needs active leaders rather than reactive ones.22 These leaders are aware of the transformation dynamics, they are oriented to the external and the internal worlds, they see the people and process dynamics knowing that they are keys to lead the change, they try to increase their own awareness consciously about how the people and their organizations are changing, and they can work and lead in a transformative way.21,22

Nurses’ perceptions of their organizations’ readiness and willingness for change are important; they help in introducing, managing, and maintaining the change. Studying factors that influence organizational readiness for changes will help in understanding readiness for change and shed the light on strategies needed to manage change effectively.

Readiness for change in organizations is linked to the culture of an organization. Anderson and Anderson stated that if the organization’s culture is not consciously considered during the transformation, the effort may fail or struggle.22

This study aimed to assess Jordanian hospitals’ readiness and willingness for change, according to nurses’ perception and as differentiated by the type of hospital (government or private) and the gender of nurse, as it will help in identifying need for targeted intervention to improve readiness for change. The aims of this research were to find answers for the following questions: 1) What are the differences in demographic variables between the government and the private hospitals? 2) What are the perceptions of Jordanian nurses about their hospital readiness for change? 3) What are nurses’ perception for readiness for change differences between the private hospitals and the government hospitals? 4) What are the nurses’ gender differences in their perceptions about hospitals’ readiness for change? and 5) What are the relationships between readiness for change in the organization and the study demographics?

Methods

Ethical statement

Before data collection, the Institutional Review Board of Jordan University of Science and Technology approved the study protocol, the methodology of the research, anonymity of the participants, the protection of identity, privacy, and handling of the data. The participants were told that completing and submitting the survey automatically meant that they gave consent. The participants did not receive any incentives for participating in the study.

Design and instruments

This was a quantitative comparative research design that used a structured questionnaire to collect data in 2010 over 2 weeks. In this comparative study, the instrument was used to estimate the readiness for change in the organization.23 The instrument was used without translation because English is the official language of nursing education in Jordan. This is a 13-item instrument with a 5-point Likert scale that is rated as follows: 1 – do not know, 2 – strongly disagree, 3 – disagree, 4 – agree, and 5 – strongly agree. This instrument was established by the researcher for educational purposes. A pilot study was conducted with 15 nurses before the actual data collection took place in this study. No changes were made, and reliability was checked through Cronbach’s alpha;24 it was 0.75 in the pilot study and 0.89 in the whole study. The second part of the instrument consisted of questions about sample demographics.

The readiness of organizations for change was conceptually defined as the ability of an organization to manage change12 and was operationally defined according to Grossman and Valiga23 as follows: encourage innovation to adopt change; plan strategically; focus on patients’ satisfaction and quality of care as indictors of successful change; use shared decision-making process; promote education, advanced nursing practice, the continuity of care, authority, and teamwork; and focus on organization marketability.

Settings and sample

This study involved four government and three private hospitals. Nurses were recruited using a convenience sampling technique. In this study, from a possible 220 participants, only 130 nurses responded, 43 males and 87 females, who were employed in hospitals located in the capital Amman and two other large governorates, resulting in a response rate of 59%. For a full understanding of change and the ability to manage it, the inclusion criterion was set as “RNs who have worked in hospitals for at least 1 year”. The exclusion criteria were based on the educational level and experience. Practical nurses and those RNs who had less than 1 year of experience were excluded.

Data analyses

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (version 20) was used to analyze data,25 considering 0.05 as the significance level. Descriptive statistics for sample variables including means, frequencies, and standard deviations were calculated. The demographic variables of the sample were categorical; accordingly, chi-square tests were used to perform comparisons. Items of the “readiness for change in organizations” instrument were treated as continuous variables, and thus, independent t-tests were used to compare different types of hospitals. The readiness of organizations for change scores were compared based on gender using the t-test. Correlations were found between the organizational readiness for change and sample demographics.24

Results

The first research question yielded significant differences in the sample demographics (p=001), as indicated in Table 1.

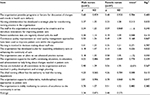

With the answers of the second research question, an average score of the “readiness of organizations for change” was calculated by adding the scores of the 13 items and was then divided by the number of scale items. Descriptive statistics were used for each item of the “readiness of organizations for change” scale in the whole sample.

Since the instrument was rated on a 5-point scale, items with a mean value of 4 or more were considered as a positive factor which indicated the readiness of organizations for change. The mean score of the organizations’ readiness for change for the whole sample was 3.43, which indicates that there are some issues in Jordanian hospitals, indicating that the organizations were not ready for change.

Although this was not the primary purpose of this research, we used the individual items of the scale to assess readiness for change in the organization. The results are presented in Table 2.

| Table 2 Means, SDs, and frequencies of nurses’ perceptions about readiness of hospitals for change in the whole sample (N=130) Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation. |

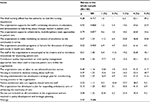

Based on the type of hospital, the third research question indicated that the average score of the readiness for change in the organizations was 3.42 for the private hospitals and 3.44 for the government hospitals. Using the individual items of the scale, the only significant difference between the private and government hospitals was in the item “the organization supports collaborative, multidisciplinary team approaches to patient care” ( =3.60 for private vs

=3.60 for private vs  =3.93 for government hospitals; p=042). The results are presented in Table 3.

=3.93 for government hospitals; p=042). The results are presented in Table 3.

Based on the gender of nurses, the fourth research question showed that the mean score of the readiness for change in organizations was 3.34 for male nurses and 3.48 for female nurses. Using the individual items of the scale, the only significant difference between male and female nurses was in the item “the organization uses or plans to use advanced practice nurses” ( =3.18 for males vs

=3.18 for males vs  =3.58 for females; p=050). The results are presented in Table 4.

=3.58 for females; p=050). The results are presented in Table 4.

With the answers for the fifth research question, correlations were estimated between the total score of organizational readiness for change and sample demographics. At 0.05, a significant, but negative correlation was found between the total score of organizational readiness for change and age (r=261). At 0.01, a significant, but negative correlation was found between the total score of organizational readiness for change and age (r=197).

Discussion

Assessing readiness for change is generally the first step in any change project. Until participants are ready for change, little can be done to bring about the change.

Taking into consideration the small sample size, differences in sample demographics are congruent with the general trend of the nursing taskforce in Jordan. That is, the majority of nurses who were employed in government hospitals had originally graduated from government schools that gave associate degrees in nursing. Also, some nurses who retired from government hospitals returned to work through special contracts in private hospitals. The majority of nurses were young; older nurses usually leave the country to work in other countries because outside jobs offer them higher salaries than those offered in Jordan. The financial situation of the government hospitals in Jordan was generally fair to poor, as compared with that in private hospitals. Contrary to what was reported by nurses in this study, government hospitals usually have a higher average daily census than private hospitals; patient care in government hospitals is usually provided at a nominal rate. Also, opposite to what was reported by nurses in this study, government hospitals usually employ full-time nurses, while private hospitals employ more part-time nurses.

In this study, nurses perceived that hospitals in Jordan were not ready for change.

In general, the literature about organizational readiness for change is limited; some studies have focused only on the private sector2,26 and none of the studies reported any gender differences.8,27 Based on the type of hospital, the results of this study showed significant differences between government and private hospitals in their readiness for change, except that the government hospitals were perceived as better in supporting collaborative and multidisciplinary work in areas related to patient care.10 This situation could be related to the fact that nursing shortage is more severe in government hospitals, requiring more teamwork among the nurses themselves and collaboration with other teams.10

Based on gender, female nurses reported a slightly higher score than male nurses; that is, female nurses perceived that their hospitals were more ready for change in their using or planning to use advanced practice nurses. In Jordan as well as in other countries, there are mostly women in the field of nursing, and thus, differences related to gender should be interpreted with caution.

Although many factors appear to influence the readiness of organizations for change, interpretation of correlational factors should be done with caution because of the issue of collinearity.

The classical change theory is commonly used in research about change and readiness for change.28 The researcher identified three phases through which the change agent must proceed before a planned change becomes a part of the system. In the unfreezing stage, the change agent unfreezes forces that maintain the status quo, thus people must believe that the change is needed. The movement in which the change agent identifies, plans, and implements appropriate strategies, ensuring that driving forces exceed restraining forces. In refreezing, the change agent assists in stabilizing the system change, so that it becomes integrated into the status quo; thus, the change agent must be supportive and should reinforce the individual adaptive efforts of those influenced by the change.29,30

A planned change, in contrast to an accidental change, is a change that results from a well-thought out effort to make something happen. Nurses can assess their readiness for change as well as the readiness of their organizations to help prepare clients for health work, create the necessary conditions to foster readiness, and assume the roles that help them prepare for change.

Results of this study have implications for practice, research, and education. For practice, regardless of type of hospital, Jordanian nurses perceived that their hospitals were not ready for change, suggesting that nurses and nursing administrators should work in a collaborative manner to introduce and adapt to change.3–5,18 Techniques for promoting this are described well in the literature.4,11

Private hospitals should focus more on collaborative and multidisciplinary work.10 Also, male nurses should be encouraged to work toward advanced nursing practice. Because these were reported as the lowest means, all health care organizations should assess regularly their patient satisfaction data and share them with their staff, as these are significant indicators of quality of care and the survival of health care organizations.31

For research that supports change and facilitate its introduction and management, readiness should be assessed. The role of nursing in change management readiness should be studied, identified, and expanded. In future studies, the use of one of the change theories as a framework for studying the concept of organizational readiness for change and a larger sample with a longer multidimensional scale is recommended. Further research should be conducted with multiple health care disciplines using the same instrument. The influence of gender and type of health care facility should also be studied in future.

Regarding education, all schools of nursing in private or government universities in Jordan provide a course about nursing leadership and management. This should include change and change management.10 All nurses who hold associate degrees have to be encouraged and allowed to obtain their Bachelor’s degrees through bridging programs. Nurses and nursing leaders should have continuing education programs through courses and workshops focused on the concept of organizational change and its related variables. As autonomy and teamwork are antecedents to change process, student autonomy and teamwork should be encouraged;10,18 today’s students are tomorrow’s nurses.

Conclusion

In general, Jordanian nurses perceived that their hospitals were not ready for change. Perceptions about organizational readiness for change varied according to the type of hospital and the gender of nurse. Government hospitals were more ready to change than private hospitals, particularly in supporting collaborative and multidisciplinary team approaches to patient care. More than male nurses, female nurses perceived that their organizations were ready to use or plan to use advanced practice nurses.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank all nurses who devoted their time and efforts to participate in this study.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Vezzetti E, Violante MG, Marcolin F. A benchmarking framework for product lifecycle management (PLM) maturity models. International Journal, Advances Manufacturing Technology. 2013. Available from http://porto.polito.it/2522090/. Accessed March 28, 2017. | ||

Su H, Hsieh P, Yeh M, Lin J. Organizational change and reshaping the nursing profession. J Nurs China. 2003;50(2):17–23. | ||

Bouckenooghe D, Devos G, van den Broeck H. Organizational change questionnaire-climate of change, processes, and readiness: development of a new instrument. J Psychol. 2009;143(6):559–599. | ||

Caldwell SD, Roby-Williams C, Rush K, Ricke-Kiely T. Influences of context, process and individual differences on nurses’ readiness for change to magnet status. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(7):1412–1422. | ||

Mustain JM, Lowry LW, Wilhoit KW. Change readiness assessment for conversion to electronic medical records. J Nurs Adm. 2008;38(9):379–385. | ||

Nelson L. Managing the human resources in organizational change: a case study. Res Prac Hum Resour Manag. 2005;13(1):55–70. | ||

Decker D, Wheeler GE, Johnson J, Parsons RJ. Effect of organizational change in the individual employee. Health Care Manag. 2001;19(4):1–12. | ||

Vakola M, Nikolaou I. Attitudes towards organizational change. What is the role of employees’ stress and commitment? Employee Relations. 2005;27(2):160–174. | ||

Kuokkanen L, Suominen T, Rankinen S, Kuokkanen ML, Savikko N, Doran D. The relationship between nursing leadership and patient outcomes: a systematic review. J Nurs Manag. 2007;15:500–507. | ||

Gill R. Change management or change leadership? J Change Manag. 2001;3(4):307–318. | ||

Maurer R. Building a foundation for change. J Qual Participat. 2001;24(3):38–39. | ||

Lehman WEK, Greener JM, Simpson DD. Assessing organizational readiness for change. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;22(4):197–210. | ||

Devereaux MW, Drynan AK, Sara Lowry S, et al. Evaluating organizational readiness for change: a preliminary mixed-model assessment of an interprofessional rehabilitation hospital. Healthc Q. 2006;9(4):66–74. | ||

Texas Commission on Alcohol and Drug Abuse. Statewide Results of the Organizational Readiness to Change Survey. Austin: Texas Commission on Alcohol and Drug Abuse; 2003. | ||

Iverson RD. Employee acceptance of organizational change: the role of organizational commitment. Int J Hum Resour Manag. 1996;7(1):122–149. | ||

Lewin K. Field Theory in Social Sciences. New York, NY: Harper & Row; 1951. | ||

Rudan VT. The best of both worlds: a consideration of gender in team building, J Nurs Adm. 2003;33(3):179–186. | ||

Ingersoll GL, Kirsch JC, Merk SE, Lightfoot J. Relationship of organizational culture and readiness for change to employee commitment to the organization. JNurs Adm. 2000;30(1):11–20. | ||

Sabo K, Duff M, Purdy B. Building leadership capacity through peer career coaching: a case study. Nurs Leadersh (Tor Ont). 2008;21(1): 27–35. | ||

Harris A, Lambert L. Building Leadership Capacity for School Improvement. What Is Leadership Capacity?; 2003. Available from: http://networkedlearning.ncsl.org.uk/knowledge-base/think-pieces/what-is-leadership-capacity-2003.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2009. | ||

Anderson LA, Anderson D. Awake at the Wheel: Moving beyond Change Management to Conscious Change Leadership; 2008. Available from: http://changeleadersnetwork.com/free-resources/awake-at-the-wheel-moving-beyond-change-management-to-conscious-change-leadership. Accessed July 28, 2009. | ||

Grossman S, Valiga TM. The New Leadership Challenge: Creating The Future of Nursing. Philadelphia: FA Davis; 2004. | ||

Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing Research: Principles and Methods. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 2004. | ||

IBM Corp. Released 2011. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. | ||

Ezell M, Casey E, Pecora PJ, et al. The results of management redesign: a case study of a private child welfare agency. Adm Soc Work. 2002;26(4):61–79. | ||

Lubatkin M, Powell G. Exploring the influence of gender on managerial work in a transitional, eastern European nation. Human Relations. 1998;51(8):1007–1031. | ||

Lewin K. Field Theory in Social Sciences. New York, NY: Harper & Row; 1951. | ||

Huber D. Leadership and Nursing Care Management. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 2006. | ||

Marquis BL, Huston CJ. Leadership Roles and Management Functions in Nursing: Theory & Application. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 2006. | ||

Johansson P, Oleni M, Fridlund B. Patient satisfaction with nursing care in the context of health: a literature review. Scand J Caring Sci. 2002;16(4):337–344. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.