Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

Moderated Mediation Model for the Association of Educational Identity and Career Identity Development of Physical Education Students

Authors Yiming Y , Kayani S , Alghamdi AA , Liu J

Received 8 May 2023

Accepted for publication 17 August 2023

Published 4 September 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 3573—3581

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S417532

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Yikeranmu Yiming,1 Sumaira Kayani,2 Abdulelah Ahmed Alghamdi,3 Jinhua Liu4

1Physical Education School, Shaanxi Normal University, Sports Learning Science Laboratory, Xi’an, Shaanxi, People’s Republic of China; 2Department of Applied Psychology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada; 3Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah, 24382-4752, Saudi Arabia; 4School of Rehabilitation, Kunming Medical University, Kunming, 650500, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Sumaira Kayani; Jinhua Liu, Email [email protected]; [email protected]

Introduction: Education and vocation are crucial to one’s identity. The current study aimed to see the association between educational identity and career identity development among Chinese PE students. The mediating effect of self-efficacy on educational identity and career identity was explored. Further, the study intended to see the moderating role of gender for the mediating effect of self-efficacy between educational identity and career identity development.

Methods: A total of 369 (age range= 16– 22) Chinese PE students were recruited as participants in the study. There were 180 (48.8%) males and 189 (51.2%) females in the sample. Hayes process model 58 was applied to develop a moderated mediation model.

Results: The results reported that there was a significant positive association between educational identity with self-efficacy and career identity. However, self-efficacy was not related to career identity. Further, self-efficacy did not play a mediating role between educational identity and career identity development. On the other hand, gender significantly moderated the mediating effect of self-efficacy between educational identity and career identity development.

Discussion: The study suggests that individuals who have a strong sense of educational identity are more likely to possess higher levels of self-efficacy and a clearer understanding of their career goals. However, it is notable that self-efficacy did not directly impact career identity, suggesting the presence of other factors influencing this aspect of identity formation. Interestingly, moderating role of gender suggests that the influence of self-efficacy on career identity development may vary depending on one’s gender, highlighting the importance of considering gender-specific factors in career-related interventions and counseling programs. The practical and theoretical implications of the study are discussed.

Implications: The practical implications of this study suggest the importance of educational identity, the need for comprehensive career counseling interventions, and the consideration of gender-specific factors. The theoretical implications contribute to identity development theory, mediation and moderation frameworks, and cross-cultural research on career identity.

Keywords: educational identity, self-efficacy, career identity development, adolescents, physical education students

Introduction

At a very young age, individuals learn to define and pursue long-term objectives, as well as develop the ability to modify their goals to change social settings.1 A large number of the goals young people create and pursue in this period revolve around the domains of education and vocation.2 An educational institution is considered a dominant social context for adolescents as they learn and set future goals, thus developing themselves in that setting.3 The major goal of education is to develop the overall personality of an individual and prepare him or her for future work and life, by making them able to internalize the association between education and work to learn basic skills for a better future.4,5 Hence, it is perceived that adolescents’ educational and vocational identities should be interconnected to enable them to learn during their education to develop vocational skills.

Educational identity refers to the aims and ideals that people research and then pursue in the educational realm.2 The three-factor identity model reflects this domain of identity in the field of education.6 This approach conceptualizes identity development as the interaction of three interrelated educational identity processes: commitment, in-depth investigation, and rethinking of commitment. These processes coexist in the dynamic of two identity cycles: the identity formation cycle, which creates strong educational commitments by abandoning goals that are no longer satisfactory, and the identity maintenance cycle, which strengthens current educational commitments through in-depth exploratory pursuits.2,7,8 The research on educational identity shows that it plays a significant role in the adaptive development of adolescents.9 Strong educational commitments and educational identity are positively associated with high levels of well-being among adolescents.10,11

Further, career identity is a major component of self-concept that is defined by the clarity, coherence, and consistency of perceived vocational motivation and talents. In infancy and adolescence, vocational identity undergoes a series of developmental changes as a consequence of the self-exploration and commitment determined by the individual and his social surroundings. The process of forming a professional identity may result in the attainment of a personalized, self-selected identity, identity foreclosure, or identity confusion. In contemporary, post-industrial civilizations, having an adaptable, flexible, and self-centered professional identity is a crucial factor in achieving job success and fulfillment (Meijers, 1998). Child and adolescent vocational development include the acquisition of knowledge, beliefs, and values regarding work options and requirements, the exploration of interests that will be relevant for vocational interest development, and the development of academic aspirations, self-efficacy, expectations, and attainment (London, 1983).

A longitudinal study on educational identity and academic achievement of Romanian adolescents supported the notion that academic and educational identity leads to career identity development.12 Moreover, Negru-Subtirica and Pop2 found a significant reciprocal association between the educational and vocational identity of adolescents. Hence, it is expected that the educational identity of Chinese adolescents would also significantly affect their career identity development. Education is an important factor in selecting one’s future job path. The relationship between educational identity and career development will have long-term effects on an individual’s growth. Teenagers can develop a sense of continuity in their occupational pursuits when they have long-term commitments to their educational choices.13 Surprisingly, less work on the link between educational and occupational identity is undertaken among Chinese adolescents.14

Previous research has suggested investigating mediators between educational and career identity. A mediator worthy of consideration could be self-efficacy; which refers to the evaluation of one’s ability to plan and carry out an activity successfully.15 There are ample pieces of research in the previous literature exhibiting a positive association between self-efficacy with educational identity.16–18 Moreover, self-efficacy is also found to be positively related to an individual’s professional growth.19 Research has supported the evidence of the positive impact of self-efficacy on the career development of individuals. For example, Chan has examined the relationship between self-efficacy and job-related factors and found that self-efficacy positively predicted the career growth of college sports students.20–22 Also, a recent meta-analysis indicated that self-efficacy significantly increased career exploration among undergraduate students.23 Hence, it is expected that self-efficacy would play a significant mediating effect between educational identity and vocational development.

In addition, past research suggested that the link between educational identity and career development may vary for different moderators. Negru-Subtirica and Pop2 investigated the role of gender in the association between education and career identity development. The authors found a positive association between educational and vocational identity in a three-wave longitudinal analysis reporting that girls are more oriented towards educational exploration for vocational commitments than boys.2,24–26 Hence, it is expected that gender would play moderating role in the mediating effect of self-efficacy between educational identity and career development.

Based on the available research, we hypothesized that there would be a significant relationship between educational identity and career identity development among adolescents from the physical education field. It was expected that the patterns of identity beliefs would be different for males and females with higher educational commitment among girls. It was further predicted that self-efficacy would mediate between educational identity and career identity development. It was also expected that gender would play a significant moderating role in the association between education and career identity, and in the mediating effect of self-efficacy.

Method

Study Design

This research study was a descriptive cross-sectional study. A survey method was used to collect quantitative data.

Participants

This is a survey-type study and participation in the research was completely voluntary. The study was approved by the review board committee of the university. The population of the study was college students in China within the age range of 16–19 years. The study was delimited to the departments of physical education. A convenient sampling technique was used for the selection of respondents belonging to the physical education field. We distributed around 400 questionnaires among the students. However, 369 valid responses were returned with a response rate of 92.25%. There were 180 (48.8%) males and 189 (51.2%) females in the sample. Due to the significant gender ratio difference in physical education department, random distribution of questionnaires may lead to gender imbalance. Therefore, we randomly selected 400 students, but fixed the gender as 200 male and 200 female students.

Instruments

Educational Identity

The Chinese version of the 13-item Utrecht-Management of Identity Commitments Scale (U-MICS) was used to assess the educational identity of adolescents in the current study.27 The scale was originally developed in Dutch,28 and also validated as an English version in the previous literature.29 The scale contains 13 items, and three sub-components such as commitment to education (eg, “My education gives me certainty in life”; 5 items), in-depth exploration (items such as “I think a lot about my education”; 5 items), and reconsideration of commitment (eg, “I frequently think it would be better to try to find a different education”; 3 items). Participants responded to each item on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (does not relate to me at all) to 5 (applies to me very well). Cronbach alpha for the scale is 0.83.

Career Identity Development

Career identity development was assessed in terms of commitment making, identification with that commitment, in-depth investigation, and in-breadth exploration. It was measured by using the Chinese version of the 30-item Vocational Identity Status Assessment.30 The scale was originally developed by Porfeli, Lee, Vondracek and Weigold31 It has three factors each containing two sub-components. For example, career exploration is divided into In-Breadth Career Exploration (eg, “casually learning about careers that are unfamiliar to me to find a few to explore further”; 5 items), and In-Depth Career Exploration (eg, “learning as much as I can about the particular educational requirements of the career that interests me the most”; 5 items); career commitment is split into Career Commitment Making (eg, “I have invested a lot of energy into preparing for my chosen career”; 5 items), and Identification with Career Commitment (eg, “My career choice will permit me in order to have the kind of family life I wish to have”; 5 items), and career reconsideration is divided into Career Self-Doubt (eg, “When I tell other people about my career plans, I feel like I am being a little dishonest”; 5 items), and career flexibility (eg, “My career choice might turn out to be different than I expect”; 5 items). The internal consistency of the scale for the current study is 0.74 indicating reliability.

Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy was measured using the Chinese version of the Generalized Self-Efficacy (GSE) Scale.32 We used the updated Chinese version of the GSE which was adapted from the conventional Chinese used in Hong Kong and Taiwan (Zhang and Schwarzer 1995). The scale was translated into simplified Mandarin from mainland China. The measure had 10 items rated on a 4-point Likert scale with a range of 1 = not at all true, to 4 = precisely true. An example is, “I can solve most problems if I invest the necessary effort”. A minimum score of 10 indicated the lowest level of self-efficacy, while a maximum score of 40 indicated the highest level of self-efficacy. Each variable on the scale contains five elements. Yet, this experiment used the unidimensional scale. The internal consistency of the scale utilized in this study is 0.92, indicating a good degree of dependability.

Analysis Techniques

Data were analyzed using SPSS ver. 26. Descriptive statistics were calculated with mean and standard deviations. As recommended by Podsakoff and Organ,33 common method bias was checked. It was found that the first factor explained 29.37% of the variance showing no bias in data. The sum score for each variable was calculated to explore the educational and vocational identity patterns among adolescents. The total score on educational identity and vocational identity by males and females showed patterns across sex. Bivariate correlations were calculated to see the relationship among all variables. Moderated mediation was assessed by applying moderated mediation model 58 of Hayes PROCESS ver. 3.4.1.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

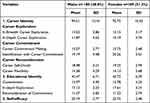

First descriptive statistics were applied to get the means and standard deviations of the variables. Detailed gender-wise identity patterns and self-efficacy are shown in Table 1. Mean values show that the overall career identity of male adolescents (M = 94.51, SD = 12.41) is higher than that of females (M = 92.75, SD = 10.45). However, career commitment making, identification with career commitment, and career self-doubt is less in males as compared to females. On the other hand, educational identity is higher in females (M = 42.72, SD = 6.39) than in males (M = 42.47, SD = 6.71). However, educational identity commitment and reconsideration are a little higher in males. In addition, the self-efficacy of males (M = 25.19, SD = 2.77) is lower than females (M = 25.75, SD = 2.48).

|

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics |

Table 2 presents gender-wise correlation among career identity, educational identity, and self-efficacy of adolescents. Career identity of adolescents is significantly positively associated with the educational identity (r = 0.367, p<0.01 for males and r = 0.281, p<0.01 for females), and self-efficacy (r = 0.571, p<0.01 for males and r = 0.670, p<0.01 for females). However, there is no relationship between educational identity and self-efficacy (r = 0.019, p>0.01 for males and r = 0.009, p>0.01 for females).

|

Table 2 Gender-Wise Correlation Among Study Variables |

Mediation Model (#4)

All the standardized regression paths of mediation models are presented in Figure 1. The results revealed that adolescents’ self-efficacy is not significantly affected by educational identity (β = 0.00, p >0.05), but self-efficacy had a significant direct effect on the career identity development of adolescents (β = 2.64, p < 0.001). Further, educational identity significantly directly predicted the career identity development of adolescents (β = 0.54, p < 0.001). Moreover, the mediation of self-efficacy between educational identity and career identity development is not significant (indirect effect = 0.022, 95% CI = −0.080, 0.121). It means educational identity does not transfer its effect to career identity through self-efficacy.

|

Figure 1 Mediation of self-efficacy between educational identity and career identity development. |

Moderated Mediation Model (#58)

After checking the mediating effect of self-efficacy between educational identity and career identity development, a moderated mediation model was developed by using the Hayes PROCESS model 58 (see Figure 2). First, self-efficacy is regressed on educational identity (a1i), gender (a2i), and the interaction between educational identity and gender (a3i). The results revealed that self-efficacy is not affected by the educational identity of adolescents (β = 0.03, p >0.05). On the other hand, there is a significant impact of gender (β = 3.77, p <0.05), and interaction term (β = 0.08, p <0.05) on self-efficacy. The findings suggest that gender plays a significant moderating role in the direct effect of educational identity on adolescents’ self-efficacy. That is the effect of educational identity on self-efficacy is significant for both males and females.

|

Figure 2 Moderated mediation model for educational identity and career identity development. |

Then, the outcome variable, career identity development, was regressed on educational identity (c’), self-efficacy (b1), gender (b2), and the interaction between self-efficacy and gender (b3). It is found that career identity development was significantly affected by educational identity ((β = 0.56, p <0.001), self-efficacy (β = 2.95, p <0.05), gender (β = 11.09, p <0.05), and the interaction between self-efficacy and gender (β = 0.55, p <0.05). It means that gender plays a significant role for the effect of educational identity on career identity development in the presence of self-efficacy. However, the indirect effect through self-efficacy was insignificant in both males (effect = 0.104, 95% CI = −0.260, 0.034) and females (effect = 0.118, 95%, CI = −0.022, 0.256). The index of moderated mediation (index = 0.222, 95%, CI = 0.024, 0.427) also confirms the moderating effect of gender on the association of educational identity and career identity development.

Discussion

The current study aimed to investigate the relationship between educational identity and career identity development of physical education students in Chinese colleges. The study further intended to see the indirect effect of educational identity on career identity development through self-efficacy. The current study broadens the existing research by examining the moderating effect of gender on the mediating effect of self-efficacy between educational identity and career identity development. The study possesses theoretical and practical significance in educational and professional fields. It contributes to the theory of career construction and social cognitive career theory.

First, it was hypothesized that educational identity would significantly predict career identity among male and female Chinese adolescents. The results indicated that there was a significant positive association between educational identity and career identity development. That is, adolescents with higher educational identity are more likely to develop career and vocational identity. The results are in line with the previous work in which the reciprocal association between educational identity and vocational identity was authenticated.2 The authors suggested that higher educational commitments facilitated the development of strong occupational commitments. These results also confirm the previous notion that a steadfast commitment to an educational direction assisted adolescents in making better career explorations and integrating these decisions into their self-system.26 It implies that students should be encouraged to develop educational and academic commitment for future career development. Further, it was also expected that the patterns of identity would be different for males and females with higher educational commitment among girls. It is found that girls and boys have different attributions toward educational identity and career identity development. There is higher career identity development in males than females indicating males have higher career identity beliefs and commitments. It means males are more likely to agree with the statements like “trying to have many different experiences so that I can find several jobs that might suit me”, and this result echoes.34 On the other hand, girls were found academically more committed than their male counterparts. They agreed more with the statement “My education gives me self-confidence”. The finding is consistent with the work of35 who found girls to be more concerned and focused on their educational endeavors. The findings suggest that educational and career development strategies must be designed according to different genders.

It was expected that self-efficacy would play a significant mediating effect between educational identity and the career development of adolescents. The results revealed that self-efficacy did not play an intermediary role in the association of educational identity with career identity. The results are opposite to previous studies which confirm the association of self-efficacy with educational identity,16–18 leading to vocational identity.36 A possible explanation could be the collectivistic nature of Chinese adolescents who perform academic and career activities for meeting the expectation of significant others not for personal satisfaction.37 It implies that the self-system of physical education students may not be important for their educational and career commitments.

Third, it was hypothesized that gender would play a moderating role in the mediation of self-efficacy between educational identity and career identity development. Our study explored that gender played a significant moderating role in the mediation of self-efficacy between educational identity and career identity development; however, the indirect path was insignificant. The finding is consistent with a recent study in which gender moderated the association of educational identity and career identity indicating a significant path from educational identity to vocational identity among girls.2 A possible explanation could be that girls are more involved in identity construction and maintenance processes than boys,24 particularly when identity strivings are studied in the vocational domain.38 Thus, it is necessary to pay attention to gender roles when educational and career identity enhancement is considered.

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

The study gives us a deeper understanding of the moderating role of gender in the self-system as a mechanism between educational identity and career identity development of adolescents from the physical education field. The study might be a pioneer one to develop a concurrent model for the variables. However, the study has a few limitations to address in further investigations. First, we evaluated identity processes using self-reported questionnaires. The respondents may find issues in giving views on the prescribed response scale. We may, however, integrate narrative accounts of identity-central personal occurrences in the educational and professional domains in future research studies. Further, the study is cross-sectional. Collecting data at different time points to see longitudinal effects may generate better results. Another limitation of the study is the small sample from only one region in China. The researchers are recommended to collect data from other areas of the country to have a representative sample. Moreover, the study has reported associations between variables (eg, educational identity with self-efficacy and career identity), and did not provide information about the directionality of these relationships or whether they are causal in nature. Establishing causality requires rigorous study designs, such as longitudinal studies or experimental designs, which have not been employed in the present study. Hence, further research is necessary to confirm and expand upon the current findings.

Conclusion

To conclude, a positive and strong relationship was found between educational and vocational identity. Career identity in males is higher than that of females indicating the significant difference between male and female students. However, the educational identity of females is comparatively high. Further, the mediating effect of self-efficacy between educational identity and vocational identity was not statistically significant. On the other hand, gender played a significant moderating role in the mediation of self-efficacy between educational identity and career identity. The study suggests that individuals who have a strong sense of educational identity are more likely to possess higher levels of self-efficacy and a clearer understanding of their career goals. However, it is notable that self-efficacy did not directly impact career identity, suggesting the presence of other factors influencing this aspect of identity formation. The study suggested considering gender roles in the academic and professional domains of identity development. Interestingly, moderating role of gender suggests that the influence of self-efficacy on career identity development may vary depending on one’s gender, highlighting the importance of considering gender-specific factors in career-related interventions and counseling programs. The study suggested considering gender roles in the academic and professional domains of identity development. The practical and theoretical implications of the study are discussed. Implications: The practical implications of this study suggest the importance of educational identity, the need for comprehensive career counseling interventions, and the consideration of gender-specific factors. The theoretical implications contribute to identity development theory, mediation and moderation frameworks, and cross-cultural research on career identity.

Recommendations

The study’s results recommend adding to the above conclusion:

- Future study should examine cultural and societal implications on educational and career identities. Identity development in different cultural contexts can help explain educational and vocational identity since the study focused on Chinese college students.

- Educators, counsellors, and policymakers must recognise gender variations in educational and career identity development. Career development outcomes can be improved by designing interventions and support systems that address male and female student needs and objectives.

- Self-efficacy did not mediate the association between educational identity and career identity in this study, but additional mediators should be investigated. Motivation, goal-setting, and social support may be mediators in future research.

- To improve generalizability, future studies should use longitudinal designs and a more diverse and representative population.

- Qualitative research approaches like interviews and focus groups can enhance our understanding of educational and vocational identity development.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Compliance with Ethical Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Kunming Medical University (KMMU2022MEC119).

Informed Consent

All participants signed an informed consent before participating in the study. Participants under the age of 18 had signed an informed consent on their behalf and their parents were informed.

Acknowledgment

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia for supporting this research work through project number: (IFP22UQU4280253DSR071).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Malin H, Liauw I, Damon W. Purpose and character development in early adolescence. J Youth Adolesc. 2017;46(6):1200–1215. doi:10.1007/s10964-017-0642-3

2. Negru-Subtirica O, Pop EI. Reciprocal associations between educational identity and vocational identity in adolescence: a three-wave longitudinal investigation. J Youth Adolesc. 2018;47(4):703–716. doi:10.1007/s10964-017-0789-y

3. Boldureanu G, Ionescu AM, Bercu A-M, Bedrule-Grigoruță MV, Boldureanu D. Entrepreneurship education through successful entrepreneurial models in higher education institutions. Sustainability. 2020;12(3):1267. doi:10.3390/su12031267

4. Arnold WW. Strengthening college support services to improve student transitioning to careers. J Coll Teach Learn. 2018;15(1):5–26. doi:10.19030/tlc.v15i1.10198

5. Ryba TV, Stambulova NB, Selänne H, Aunola K, Nurmi J-E. “Sport has always been first for me” but “all my free time is spent doing homework”: dual career styles in late adolescence. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2017;33:131–140. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.08.011

6. Crocetti E. Identity formation in adolescence: the dynamic of forming and consolidating identity commitments. Child Dev Perspect. 2017;11(2):145–150. doi:10.1111/cdep.12226

7. Crocetti E. Identity dynamics in adolescence: processes, antecedents, and consequences. Eur J Dev Psychol. 2018;15(1):11–23. doi:10.1080/17405629.2017.1405578

8. Meeus W. The identity status continuum revisited. Eur Psychol. 2018;23(4):289–299. doi:10.1027/1016-9040/a000339

9. Flum H, Kaplan A. Identity formation in educational settings: a contextualized view of theory and research in practice. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2012;37(3):240–245. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2012.01.003

10. van Rens FE, Ashley RA, Steele AR. Well-being and performance in dual careers: the role of academic and athletic identities. Sport Psychol. 2019;33(1):42–51. doi:10.1123/tsp.2018-0026

11. Karaś D, Cieciuch J, Negru O, Crocetti E. Relationships between identity and well-being in Italian, Polish, and Romanian emerging adults. Soc Indic Res. 2015;121(3):727–743. doi:10.1007/s11205-014-0668-9

12. Pop EI, Negru-Subtirica O, Crocetti E, Opre A, Meeus W. On the interplay between academic achievement and educational identity: a longitudinal study. J Adolesc. 2016;47(1):135–144. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.11.004

13. Rogers ME, Creed PA, Praskova A. Parent and adolescent perceptions of adolescent career development tasks and vocational identity. J Career Dev. 2018;45(1):34–49. doi:10.1177/0894845316667483

14. Ramaci T, Pellerone M, Ledda C, Presti G, Squatrito V, Rapisarda V. Gender stereotypes in occupational choice: a cross-sectional study on a group of Italian adolescents. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2017;10:109–117. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S134132

15. Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986.

16. Vogel FR, Human-Vogel S. Academic commitment and self-efficacy as predictors of academic achievement in additional materials science. High Edu Res Dev. 2016;35(6):1298–1310. doi:10.1080/07294360.2016.1144574

17. Hakyemez TC, Mardikyan S. The interplay between institutional integration and self-efficacy in the academic performance of first-year university students: a multigroup approach. Int J Manage Edu. 2021;19(1):100430. doi:10.1016/j.ijme.2020.100430

18. Taghani A, Razavi MR. The effect of metacognitive skills training of study strategies on academic self-efficacy and academic engagement and performance of female students in Taybad. Curr Psychol. 2021;2021:1–9.

19. Wendling E, Sagas M. An application of the social cognitive career theory model of career self-management to college athletes’ career planning for life after sport. Front Psychol. 2020;11:9. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00009

20. Chan -C-C. The relationship among social support, career self-efficacy, career exploration, and career choices of Taiwanese college athletes. J Hosp Leis Sports Tour Educ. 2018;22:105–109. doi:10.1016/j.jhlste.2017.09.004

21. Chan -C-C. Factors affecting career goals of Taiwanese college athletes from perspective of social cognitive career theory. J Career Dev. 2020;47(2):193–206. doi:10.1177/0894845318793234

22. Chan -C-C. Social support, career beliefs, and career self-efficacy in determination of Taiwanese college athletes’ career development. J. Hosp Leis Sports Tour Educ. 2020;26:100232. doi:10.1016/j.jhlste.2019.100232

23. Kleine A-K, Schmitt A, Wisse B. Students’ career exploration: a meta-analysis. J Vocat Behav. 2021;131:103645. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2021.103645

24. Klimstra TA, Hale WW

25. Negru-Subtirica O, Pop EI, Crocetti E. Developmental trajectories and reciprocal associations between career adaptability and vocational identity: a three-wave longitudinal study with adolescents. J Vocat Behav. 2015;88:131–142. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2015.03.004

26. Negru-Subtirica O, Pop EI, Crocetti E. Good omens? The intricate relations between educational and vocational identity in adolescence. Eur J Dev Psychol. 2018;15(1):83–98. doi:10.1080/17405629.2017.1313160

27. Crocetti E, Cieciuch J, Gao C-H, et al. National and gender measurement invariance of the Utrecht-management of identity commitments scale (U-MICS) A 10-nation study with university students. Assessment. 2015;22(6):753–768. doi:10.1177/1073191115584969

28. Crocetti E, Rubini M, Palmonari A. Attaccamento ai genitori e al gruppo dei pari e sviluppo dell’identità in adolescenti e giovani. Psicol Clin Dello Sviluppo. 2008;12(2):331–356.

29. Stringer KJ, Kerpelman JL. Career identity development in college students: decision making, parental support, and work experience. Identity. 2010;10(3):181–200. doi:10.1080/15283488.2010.496102

30. Zhang J, Chen G, Yuen M. Validation of the Vocational Identity Status Assessment (VISA) using Chinese technical college students. J Career Assess. 2019;27(4):675–692. doi:10.1177/1069072718808798

31. Porfeli EJ, Lee B, Vondracek FW, Weigold IK. A multi-dimensional measure of vocational identity status. J Adolesc. 2011;34(5):853–871. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.02.001

32. Zeng G, Fung S-F, Li J, Hussain N, Yu P. Evaluating the psychometric properties and factor structure of the general self-efficacy scale in China. Curr Psychol. 2020;2020:1–11.

33. Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

34. Chen S, Chen H, Ling H, Gu X. How do students become good workers? Investigating the impact of gender and school on the relationship between career decision-making self-efficacy and career exploration. Sustainability. 2021;13(14):7876. doi:10.3390/su13147876

35. Voyer D, Voyer SD. Gender differences in scholastic achievement: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2014;140(4):1174. doi:10.1037/a0036620

36. Green ZA. The mediating effect of well-being between generalized self-efficacy and vocational identity development. In. J Educ Vocat Guid. 2020;20(2):215–241. doi:10.1007/s10775-019-09401-7

37. Lu L. Culture, self, and subjective well-being: cultural psychological and social change perspectives. Psychologia. 2008;51(4):290–303. doi:10.2117/psysoc.2008.290

38. Solomontos-Kountouri O, Hurry J. Political, religious and occupational identities in context: placing identity status paradigm in context. J Adolesc. 2008;31(2):241–258.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.