Back to Journals » International Journal of Women's Health » Volume 13

Long-Term Efficacy of Physical Therapy for Localized Provoked Vulvodynia

Authors Jahshan-Doukhy O, Bornstein J

Received 14 December 2020

Accepted for publication 23 January 2021

Published 10 February 2021 Volume 2021:13 Pages 161—168

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S297389

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Everett Magann

Ola Jahshan-Doukhy,1 Jacob Bornstein2

1Azrieli Faculty of Medicine, Bar-Ilan University, Safed, Israel; 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Galilee Medical Center, Nahariya, Israel

Correspondence: Jacob Bornstein Email [email protected]

Purpose: The origin of provoked vulvodynia (PV), the main cause of entry dyspareunia, remains unclear, and the treatment is empiric. In this study, we aimed to investigate the long-term effects of physical therapy on PV in subjects using questionnaire concerning PV symptoms immediately after physical therapy and at least 10 years later.

Patients and Methods: This study included a total of 24 women diagnosed with PV and referred by their primary physicians to Maccabi Physical Therapy Clinic for pelvic floor rehabilitation between 2004 and 2008. Criteria such as pain relief, sexual functioning, and treatment satisfaction were assessed.

Results: The average pain scores of the 24 participants reduced significantly after therapy, and 42% had no pain between treatment and the time of survey. Eighty-three percent did not undergo additional treatment after the initial physical therapy and reported high or very extremely high levels of pain reduction following treatment. Multiple regression analysis found that onset type of PV and age were not associated with the treatment outcome (p = 1.0).

Conclusion: Physical therapy is an effective long-term treatment for primary or secondary PV, resulting in pain reduction and improved sexual function.

Keywords: dyspareunia, pain management, vulvodynia, physical therapy, vestibulodynia

Introduction

Vulvodynia is a chronic condition involving vulvar pain of at least 3-month duration, without an identifiable cause, which may have associated pathophysiological factors.1,2 One common presentation of vulvodynia is pain in the vestibule that results from intercourse or touch and is called provoked vulvodynia (PV) or vestibulodynia, a condition formerly referred to as “vestibulitis” or “vulvar vestibulitis syndrome.”3 The primary form of PV occurs when women experience pain at first introital touch.4 Women who had pain-free vaginal penetration before symptom onset are considered to have secondary PV. This chronic condition interferes with several aspects of women’s quality of life. Typically, women with PV spend years experiencing pain before receiving the correct diagnosis and treatment.

The etiology of PV remains unclear; hence, PV treatment is empiric and includes physical therapy, pharmacological approaches, psychological/sexual therapy, and surgery. The rationale for physical therapy in women with PV is that they have high pelvic floor muscle tone along with poor endurance and coordination and difficulty in muscle control and relaxation.5 Pelvic floor physical therapy may include methods such as soft tissue and general relaxation techniques, electrical stimulation, pelvic floor exercises, vaginal dilatation, and biofeedback therapy.4 On a short term, treating PV with physical therapy has been shown to be successful in 60–70% of cases.5,6

Current studies have evaluated only short-term outcomes; therefore, this study investigated the long-term effects of physical therapy. Pain relief, sexual functioning, and treatment satisfaction were assessed in women diagnosed with PV who were treated at least 10 years ago. Moreover, the degree of treatment success was assessed according to the onset type of PV (primary/secondary) and the age of women.

Patients and Methods

This study is a historical observational cohort study. It was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki: the study received approval from institutional review board committee prior to starting it: Maccabi health services (approval number 0007-19-BBL on March 31, 2019). Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

This study included women diagnosed with PV and referred by their primary physicians to Maccabi physical therapy clinic for physical therapy for pelvic floor rehabilitation between 2004 and 2008. Patients’ charts were randomly selected from the Maccabi healthcare physical therapy database using a computer randomization method.

Inclusion criteria were a complaint of severe entry dyspareunia with a confirmed PV diagnosis by a vulvar specialist after testing the vestibule using a Q-tip, pressing on foci throughout the vestibule. Patients were between 18 and 35 years of age at the time of treatment and were treated with a single series of physical therapy treatments for pelvic floor muscles at least 10 years before the start of the present study. Women who underwent prior treatment, more than one treatment modality, or more than one series of physical therapy were excluded. Additionally, women whose physical therapy series included fewer than three sessions and those diagnosed with additional vulvovaginal diseases were excluded.

The sample size calculation showed that enrolment of 23 women with an alpha of 0.05 would provide 80% power to detect a resolution of dyspareunia.

Study Questionnaire

Data was collected using a validated Hebrew-translated questionnaire used in previous PV studies and adapted to the present study. The questionnaire was administered by a study coordinator who was not involved in the care of any study participant. The questionnaire included sections on demographics, obstetric history, and pain characteristics and intensity and its effect on sexual and daily functioning. The questionnaire was based on the modified Brief Pain Inventory,7 McGill Pain Questionnaire,8 and international society of vulvovaginal disease vulvodynia questionnaire.9

Pain intensity before treatment and at the time of the study was measured in a list of activities known to cause pain in the vulva, with a numeric rating scale where the patient was asked to rate the pain from 0 (lowest) to 10 (highest) before and after treatment. The effect of pain on sexual functioning was measured by questions examining the frequency of sexual intercourse in the post-treatment period and at the time of the survey (with responses ranging from non-existent to full sexual intercourse as desired). PV onset type was assessed by asking whether the pain immediately appeared on the first attempt when having full sexual intercourse or when inserting a tampon (yes = primary provoked vulvodynia; no = secondary provoked vulvodynia).

Women were asked about the time to maximum improvement in symptoms after undergoing therapy. The degree of treatment satisfaction was measured by patients’ perception of change due to treatment (ranging from a very marked change to a very severe deterioration). They were further asked about their willingness to undergo treatment again or recommend it to a friend suffering from the same problem. Details were requested for any additional treatment or counseling since physical therapy and the reason for receiving additional treatment (because the original treatment was not at all or only partially helpful or some other reason).

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software version 23 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Normally distributed data were presented as mean and standard deviation and non-normally distributed data as median and interquartile range. Categorical data were presented using percentages and prevalence. Pain reduction over time was tested using paired sample t-test. The chi-square test was used to identify factors associated with treatment success. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to examine if age and onset type of PV affected the treatment outcome.

Results

Enrolled Patients and Demographic Data

Figure 1 shows that a total of 347 patients were referred to the study center for PV treatment during the evaluation period, and 200 patient cases were randomly selected. Half of these (n = 101, 50%) were eligible to participate in the study, and 48/101 (48%) were randomly selected. Successful contacts were made with 29/48 patients (60%), and 24/29 (83%) agreed to be interviewed. Contact information was out of date for the remaining patients. At the time of treatment, most women were in their twenties, with an average age of 26.7 ± 3.9 years. At the time of survey, most women were married and living with the partner with whom they had intimate relations. The mean time since treatment was 13 ± 1 years (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Demographic Data of the Study Participants |

|

Figure 1 Flow chart of the study participants. |

Obstetric History

Most women (18/24, 75%) gave birth vaginally after physical therapy. Four of 18 (22%) did not have an episiotomy, 10 (56%) had one episiotomy, and 4 (22%) had two or more episiotomies. All but one woman (17/18, 95%) reported no recurring dyspareunia after vaginal birth or episiotomy. Only 2/24 women (8%) underwent vulvar or vaginal surgery after primary treatment, and these surgeries were unrelated to PV treatment.

Treatment Results Regarding Pain and Sexual Function

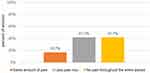

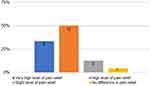

At the time of survey, 10/24 women (42%) had not experienced pain during sexual intercourse since completing the physical therapy, and the same number reported less pain since therapy. Only 4/24 (17%) reported no change in pain levels since therapy (Figure 2). Thirteen women (54%) stated that they still had mild pain during sexual activity, and two (8%) maintained that they were able to have intercourse, although the intensity of pain during intercourse was still high (Figure 3). None of the women experienced such a high degree of pain that they were unable to have sex at all or had to stop midway due to pain. The level of pain (from 0 to 10) in a variety of conditions and occurring spontaneously sharply decreased following treatment (Figure 4).

|

Figure 2 Patients’ level of pain during sexual intercourse at the time of the survey vs during the recovery period. |

|

Figure 3 Level of pain at time of survey. |

|

Figure 4 Rating of pain levels during various activities before and after treatment. Notes: **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. |

Treatment Satisfaction

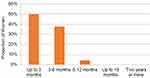

Most women (20/24, 83%) did not undergo additional treatment after the initial physical therapy and reported high or extremely high levels of pain reduction following treatment (Figure 5). Those who sought additional treatments included only topical ointments (one woman) and acupuncture (two women). Only one woman reported no change in her condition following physical therapy. Half of the women (12/24, 50%) experienced maximum improvement 3 months after therapy. For 9/24 women (37%), maximum improvement was seen in 3–6 months (Figure 6).

|

Figure 5 Satisfaction with treatment: level of pain relief following physical therapy. |

|

Figure 6 Time until maximal pain relief. |

Over 80% of women said they would undergo the same treatment again if needed, whereas a few answered that they would do so with reservations (13%). One said she would not undergo treatment again. When asked if they would recommend the treatment to their friends if they suffered from PV, majority would recommend it wholeheartedly, and a few (8%) would recommend it with reservations.

The Effect of the Onset Type of Vulvodynia on Treatment Outcomes

Primary PV was diagnosed in 15/24 (63%) patients (Table 1). There was no significant difference in symptoms before (p = 0.27) or after (p = 0.37) treatment based on the onset type of PV, and no difference in satisfaction with treatment between women with primary and secondary PV was noted (p = 0.64).

Moreover, there was no association between the onset type of PV and whether they would repeat the treatment (p = 0.23). There was no significant difference in the likelihood that patients would recommend treatment to a friend based on the onset type of PV (p = 0.45).

Furthermore, the onset type of PV and current frequency of intercourse were not significantly related (p = 0.66). Multiple regression analysis found that onset type of PV and age were not associated with the treatment outcome (p = 1.0) (Table 2).

|

Table 2 Factors Related to Treatment Outcomes |

Discussion

This study demonstrated that physical therapy is an effective long-term treatment for PV. Treatment satisfaction and sexual function were consistently high. The efficacy of treatment was confirmed regardless of age or onset type of PV. The treatment benefited the patients substantially in most of the parameters examined (sexual function, level of pain in different activities, and satisfaction with treatment).

PV, a chronic pain condition, challenges healthcare providers because its etiology and optimal care are unknown. There are several PV treatments; however, there is no consensus as to the gold standard approach. A comprehensive overview of all existing treatment approaches to vulvodynia reported that psychological counseling, pelvic floor physical therapy, and surgical treatment are the best therapeutic options.10

The treatment efficacy of PV is typically measured by pain reduction, similar to the findings of most chronic pain studies. However, pain reduction does not necessarily improve the mental and sexual well-being of patients with PV.11 Therefore, we assessed treatment efficacy by evaluating pain reduction and changes in patients’ sexual function and treatment satisfaction.

The main finding in this long-term follow-up study was similar to that reported in studies that evaluated the short-term effectiveness of physical therapy,5 showing success rates of 60–70%. However, defining therapeutic success varied between studies, and most studies were not randomized.

Regarding post-treatment improvements in sexual function, Morin et al showed that short-term studies demonstrate a significant improvement in sexual function in women undergoing physical therapy.6 It is crucial to note that all studies mentioned in that review had small and heterogeneous samples.

Another metric of treatment effectiveness is patient satisfaction, to which most women said they would undergo the treatment again and would recommend it to friends wholeheartedly.

We further found that the improvements in pain index, sexual function, and satisfaction with treatment were not affected by primary versus secondary PV or by the obstetric history. Age at the time of treatment did not affect the treatment results.

Regarding measuring the treatment results, there is a wide range of tools for assessing pain in the vestibule, including real-time pain measurements (during a physical test such as the Q-tip test), pelvic floor muscle evaluation by electromyography or ultrasound, or assessing pain based on patient self-reports.5,11,12 A review of 25 studies identified 110 different tools.5 The vast majority of these (86%) relied on participants’ self-reported improvements in their mental state, sexual function, and pain reduction, compared with 12% of the tools that relied on reports by physicians. Pukall et al based their recommendations on the initiative on methods, measurement, and pain assessment in clinical trial.12 In the present study, the efficacy of treatment was comprehensively assessed by documenting pain reduction, sexual function, and patient satisfaction.

The advantages of this study are that it examined the effectiveness of physical therapy 10 years or more after treatment. In addition, a personal interview was conducted with each participant rather than relying solely on data from the medical records. However, the study was limited due to the length of time that passed since treatment. An average of 13 years passed since the women underwent physical therapy. Memory bias in this situation may affect the retrospective recall of pain and other symptoms. However, most women in this study had recalled the pain and its nature because it affected intimate relations and sometimes prevented them from having intercourse. Another limitation was that women who did not have good outcomes from PV treatment may have been less likely to participate in a study where they talked about that treatment, which may influence results to look more positive than they would be for the general population.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that pelvic floor physical therapy is an effective treatment for women with primary or secondary PV, resulting in an excellent long-term decrease in pain levels and improved sexual functioning. While further research is needed to determine the causes of PV, pelvic floor physical therapy should be considered a method to improve patients’ quality of life.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for Publication

Obtained

Author Contributions

Both authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Bornstein J, Goldstein AT, Stockdale CK, et al. 2015 ISSVD, ISSWSH, and IPPS consensus terminology and classification of persistent vulvar pain and vulvodynia. J Sex Med. 2016;13:607–612. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.02.167

2. Pukall CF, Goldstein AT, Bergeron S, et al. Vulvodynia: definition, prevalence, impact, and pathophysiological factors. J Sex Med. 2016;13:291–304. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2015.12.021

3. Henzell H, Berzins K, Langford JP. Provoked vestibulodynia: current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2017;9:631–642. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S113416

4. Bornstein J, Preti M, Simon JA, et al. Descriptors of vulvodynia: a multisocietal definition consensus (International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease, the International Society for the Study of Women Sexual Health, and the International Pelvic Pain Society). J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2019;23:161–163. doi:10.1097/LGT.0000000000000461

5. Bergeron S, Reed BD, Wesselmann U, Bohm-Starke N. Vulvodynia. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6:1–21. doi:10.1038/s41572-020-0164-2

6. Morin M, Carroll MS, Bergeron S. Systematic review of the effectiveness of physical therapy modalities in women with provoked vestibulodynia. Sex Med Rev. 2017;5:295–322. doi:10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.02.003

7. Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the brief pain inventory. Ann Acad Med Singap. 1994;23:129–138.

8. Melzack R. The short-form McGill pain questionnaire. Pain. 1987;30:191–197. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(87)91074-8

9. David A, Bornstein J. Evaluation of long-term surgical success and satisfaction of patients after vestibulectomy. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2020;24:399–404. doi:10.1097/LGT.0000000000000552

10. Rosen NO, Bergeron S, Pukall CF. Recommendations for the study of vulvar pain in women, part 1: review of assessment tools. J Sex Med. 2020;17:180–194. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.10.023

11. Corsini-Munt S, Rancourt KM, Dubé JP, Rossi MA, Rosen NO. Vulvodynia: a consideration of clinical and methodological research challenges and recommended solutions. J Pain Res. 2017;10:2425. doi:10.2147/JPR.S126259

12. Pukall CF, Bergeron S, Brown C, Bachmann G, Wesselmann U. Recommendations for self-report outcome measures in vulvodynia clinical trials. Clin J Pain. 2017;33:756–765. doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000000453

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.