Back to Journals » Journal of Healthcare Leadership » Volume 11

Leadership and management competencies required for Bhutanese primary health care managers in reforming the district health system

Authors Dorji K , Tejativaddhana P , Siripornpibul T, Cruickshank M, Briggs D

Received 24 November 2018

Accepted for publication 9 January 2019

Published 25 March 2019 Volume 2019:11 Pages 13—21

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JHL.S195751

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Russell Taichman

Kinley Dorji,1,2 Phudit Tejativaddhana,1,3 Taweesak Siripornpibul,1,4 Mary Cruickshank,1,5 David Briggs1,6

1College of Health Systems Management, Naresuan University, Phitsanulok, Thailand; 2Ministry of Health, Royal Government of Bhutan, Thimphu, Bhutan; 3ASEAN Institute for Health Development, Mahidol University, Nakhon Pathom, Thailand; 4Faculty of Science, Department of Mathematics, Naresuan University, Phitsanulok, Thailand; 5School of Nursing and Healthcare Professions, Federation University, Mpunt Helen, VIC, Australia; 6University of New England, Armidale, NSW, Australia

Objective: This study aims to identify the required management competencies, current competency levels, and strategies for improving the management competencies of Bhutanese primary health care (PHC) managers.

Methods: A quantitative method with a cross-sectional survey using self-administered questionnaires. This study recruited 339 PHC managers across Bhutan. The data were analyzed using statistical software.

Results: This study identified three competency domains and seven key sub-domain competencies. People domain was perceived to be the highest required competency with a mean score of 4.2376, followed by execution (4.1851), and the transformation (4.0501) domains. For the seven key sub-domains, the communication sub-domain (4.3220) was perceived as the highest required competency, followed by professionalism (4.2967), managing change (4.1776), relationship building (4.1686), analytical thinking (4.1091), leadership (4.0980), and innovative thinking (3.9794). The current competency levels of PHC managers in domains and sub-domain competencies were the people domain (3.7322), execution (3.6471), and the transformation (3.5554). For the sub-domains, communication (3.8092), professionalism (3.7939), relationship building (3.6603), analytical thinking (3.6396), leadership (3.5805), managing change (3.5723), and innovative thinking (3.4543).

Conclusion: Findings of Bhutan health managers’ competencies are consistent with the findings of other international contexts. This study suggests that agencies responsible for health system need to focus more on the competencies defined by the study to positively influence health leadership and management development interventions.

Keywords: Bhutanese primary health care managers, district health system, health reform, leadership and management competency

Introduction

A district health system (DHS) is an organization that implements national health policies and plans in relation to primary health care (PHC) approaches.1 These policies and plans are closely aligned to achieve the overarching development philosophy of Gross National Happiness.2 The DHS is the backbone of the national health system.3 The DHS continues to pursue the comprehensive PHC approaches.1 Twenty district health sections in Bhutan serve a national population of 735,553.4 The health care services are delivered through 30 hospitals, 25 Basic Health Units (BHU) I, 185 BHU-II, 49 sub-post, 59 traditional health facilities, 5,028 health care staff members, 553 Outreach Clinics (ORCs), and 1,150 Village Health Workers (VHWs) scattered all across the country.5 Bhutanese enjoy free access to both modern and traditional medicines as mandated by the constitution.6 However, DHS is confronted with a host of issues such as rising health care costs, demand for higher quality health services, and shortages of medical doctors and nurses in the country.3,7–9 Besides, DHS is faced with both chronic degenerative diseases and emerging and re-merging infectious diseases.1 Disparities among rural communities exist in the utilization of health services and health outcomes.10,11 The competencies of PHC managers are not well understood, and there are no clearly defined required competencies for PHC managers in Bhutan. The DHS needs to be reformed to meet the health needs of poor people and achieve universal health coverage. Toward achieving these reforms, DHS requires competent health managers enabling effective response to the constantly changing health environments.12,13

Bhutanese PHC managers play a strategic role in managing district health services. The Deputy Chief District Health Officer (Dy. CDHO), Senior District Health Officer (Sr. DHO), and District Health Officer (DHO) are non-clinicians. The Chief Medical Officer (CMO) and Medical Officer (MO) work as clinicians as well as manage the district hospital and BHU grade-I. The Health Assistant (HA) in-charge also manages the PHC approaches at the BHU-II.

The presence of competent health managers is significant at all levels, particularly at the decentralized level of the health system.14–16 Moreover, leadership and management competencies are identified as key elements for improved health care systems.17,18 “Competency” is a set of related knowledge, skills, and abilities required to successfully perform critical work functions or tasks in a defined work setting.19 The National Center for Healthcare Leadership (NCHL; 2010) defines the three domains: “Transformation” is visioning, energizing, and stimulating a change process that unites communities, patients, and professionals around new models of health care and wellness; “Execution” is translating vision and strategy into optimal organizational performance; and “People” is defined as creating an organizational climate that values employees from all backgrounds and provides an energizing environment for them.20

The literature review revealed the three competency domains as people, execution, and transformation required for dynamic leadership roles in health care.20 Further, the scholars contend that seven key competency sub-domains are essential for functional leadership and management roles in health care settings such as 1) analytical thinking;20–22 2) innovative thinking;20,23 3) leadership;15,19,22,24,25 4) communication;15,16,20–22,24–26 5) managing change;16 6) professionalism;16 and 7) relationship building15,16,20,24–26 that can be applied across a diverse range of situations and contexts. Moreover, Briggs et al27 outlined the characteristics of a sense-making role and competencies such as managing competing interests, engagement communication, flexible thinking, understanding and managing self, interpretation and understanding, critical thinking and big picture visioning, and resilience and self-confidence.

However, PHC managers at all levels of management work with inadequate competencies and limited practical skills to solve problems, particularly in the DHSs.9 The qualities of health care services are not up to the standard.8,9 For Bhutan, understanding the required leadership and management competencies of PHC managers is significant to effectively respond to DHS reforms. Thus, this study aims to identify the required management competencies and current competency levels of PHC managers in reforming the DHS and strategies for improving competencies.

What gap this fills

What is already known: The literature confirms that presence of competent health managers is significant at all levels of the health system to meet the constantly changing health environment.

What this research adds: This paper increases the understanding of leadership and management competencies required by Bhutanese PHC managers.

Methodology and design

This cross-sectional survey was conducted across 20 districts in Bhutan, using the quantitative paradigm.28 Data were collected through self-administered questionnaires. Review from five experts was sought and an index of consistency (IOC) was 0.99.29 The instrument was piloted and the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.89.30 The total population of PHC managers during the study period was found to be 341.5 The samples for this study were derived from the super-population concepts.31 Cochran added that every finite population is a constituent part of the super population.31 This study recruited 339 managers (99.6% response rate): 13 CMOs; 43 MOs; 5 Dy. CDHOs; 17 Sr. DHOs; 11 DHOs; and 250 HA managers in-charge. The data were analyzed using statistical software.

Ethics statement

The Naresuan University Ethics Committee and the Health Ethics Board of Bhutan approved the research project.

Results

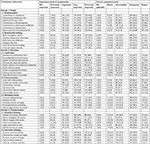

The demographic characteristic of the 339 respondents shows that the majority of respondents were male, with the group predominantly holding certificate-level qualifications, with more than 28% holding graduate/postgraduate qualifications. Table 1 further describes the extensive range of job positions, in the workplace and years of experience. The detail reflects a diverse and comprehensive sample relevant to the study.

| Table 1 Demographic characteristic of Bhutanese PHC managers (n=339) Abbreviation: PHC, primary health care. |

Importance of required management competencies of Bhutanese PHC managers

The results of the levels of importance of required management competencies of three domains and seven key sub-domains of leadership and management competencies are now presented.

As described in Table 2, the levels of importance of required competencies of the three domains are as follows: “People” (4.2376) ranked the highest, followed by “Execution” (4.2000), and “Transformation” (4.0501) was the lowest. For the sub-domain’s competencies, the levels of importance of competencies: “Communication” is the highest (4.3220), followed by “Professionalism” (4.2967); “Managing Change” (4.1776); “Relationship Building” (4.1686); “Analytical Thinking” (4.1091); “Leadership” (4.0980), and the lowest was “Innovative Thinking” (3.9794), with medium classification, as shown in Table 2.

| Table 2 Summary of the levels of importance of management competencies and current competency levels of Bhutanese PHC mangers (n=339) Notes: 1.00–1.499 (Lowest); 1.500–2.499 (Low–Medium); 2.500–3.499 (Medium); 3.500–4.499 (Medium–High); 4.500–5.000 (Highest), Data from Waleetorncheepsawat and Asiraphot.32 Abbreviation: PHC, primary health care. |

For the current competency levels: All three competency domains ranked in medium–high (3.500–4.499), however “People” (3.7322) ranked the highest, followed by “Execution” (3.6471) and “Transformation” (3.5554). The standard deviation in the three domains varied between 0.48756 and 0.48778. For the sub-domain’s current competency levels: “Communication” (3.8092) ranked the highest, followed by “Professionalism” (3.7939); “Relationship Building” (3.6603); “Analytical Thinking” (3.6396); “Leadership” (3.5805); “Managing Change” (3.5723); and “Innovative Thinking” (3.4543) was the lowest and classified into a medium, as indicated in Table 2.

Importance of required management sub-domain competencies of Bhutanese PHC managers

The descriptions of the levels of importance of required management competencies of the sub-domains are described as follows:

Domain 1: People

Sub-domain 1.1: Professionalism: The Professionalism has seven competency statements, and the top three major findings are discussed in relation to levels of importance of competencies. The competency “commitment to developing others” (163; 48.1%) ranked the highest and rated as very important, followed by “commitment to advancing the profession” (162; 47.8%) and “demonstrated professional roles” (162; 47.8%) as extremely important (Table 3).

Sub-domain 1.2: Relationship building: This sub-domain has six competency statements. “Value and respecting diversity” (171; 50.4%) was perceived as very important, followed by “team building and collaboration” (170; 50.1%) and “delegation of roles and responsibilities effectively” (167; 49.3%).

Domain 2: Execution

Sub-domain 2.1: Leadership: This sub-domain has nine competency statements. The top three findings are discussed. “Support and mentor high potential” (180; 53.1%) was viewed as very important, followed by “exhibits collective and collaborative” (173; 51.0%). “Creating an organizational climate” (142; 41.9%) was perceived as extremely important in their roles.

Sub-domain 2.2: Communication: This sub-domain has six competency statements, and the top three are “Listening with understanding” (173; 51.0%) was rated as extremely important, followed by “demonstrating effective relations” (164; 48.4%) and “verbally and visually communicating and using factual data” (161; 47.5%) as very important in their roles.

Sub-domain 2.3: Managing change: This sub-domain has five competency statements. “Respond to need” (190; 56.0%) the highest and very important, followed by “promote on-going learning” (181; 53.4%). The respondents perceived that “encouraging diversity of thoughts” (131; 38.6%) was as extremely important in their roles.

Domain 3: Transformation

Sub-domain 3.1: Analytical thinking: This sub-domain has six competency statements, and the top three findings are “Analyze and evaluate information” (183; 54.0%) and “ability to integrate information” (183; 54.0%) followed by the ability to “distinguish information” (180; 53.1%), which were seen as very important to their current roles. The ability to “judge issues based on facts and identify alternate processes” (126; 37.2 %) were perceived as extremely important to their current roles.

Sub-domain 3.2: Innovative thinking: This has five competency statements. For the levels of importance of competencies, “Promoting innovative thinking” (170; 50.1%) was the highest, and seen as very important, followed by “demonstrate courage and insight” (169; 49.9%). The competency “promoting work environment” (107; 31.6%) was perceived as extremely important to their roles.

Current management competencies of Bhutanese PHC managers

The descriptions of the sub-domains of current competency levels of Bhutanese PHC managers are described as

Domain 1: People

Under the people domain, there were two sub-domains: “Professionalism” and “Relationship Building”.

Sub-domain 1.1: Professionalism: This sub-domain has seven competency statements, and the top three major findings are discussed in relation to current competency levels. Most of the respondents rated themselves as competent followed by intermediate in demonstrating their roles. The respondents were perceived as competent in “demonstrating professional roles” (221; 65.2%) followed by “uphold and acts ethically” (217; 64.0%). However, the respondents also rated themselves as intermediate competency level in “commitment to developing others” (130; 38.3%).

Sub-domain 1.2: Relationship building: This sub-domain has six competency statements. PHC managers were found to be competent in “demonstrating value and respecting diversity” (212; 62.5%) followed by “developing interpersonal relationships” (200; 59.0%).

However, respondents also rated themselves as intermediate in areas of “delegating effectively by empowering others” (144; 42.5%).

Domain 2: Execution

Under the execution domain, there were three sub-domains: “Leadership”, “Communication”, and “Managing change”.

Sub-domain 2.1: Leadership: This sub-domain has nine competency statements; the top three findings are discussed. The majority of the respondents rated themselves as competent, followed by intermediate levels of competency in demonstrating their roles. The competency “holds self and others accountable” (208; 61.4%) was the highest, followed by “creating an organizational climate” (191; 56.3%). However, the competency “developing and communicating vision” (141; 41.6%) was rated as intermediate.

Sub-domain 2.2: Communication: This sub-domain has six competency statements, and the top three are “Listening with understanding” (224; 66.1%) was the highest, followed by “verbally and visually communicating” (215; 63.4%), and “use factual data for decision-making” (202; 59.6%).

Sub-domain 2.3: Managing change: This sub-domain has five competency statements: “Promoting ongoing learning” (188; 55.5%) was the highest, followed by “responding to needs and explore opportunities for growth” (182; 53.7%). However, the competency “anticipating and planning strategies” (143; 42.2%) was rated as intermediate competency level.

Domain 3: Transformation

Under the transformation domain, there were two sub-domains: “Analytical thinking” and “Innovative thinking”.

Sub-domain 3.1: Analytical thinking: This sub-domain has six competency statements, and the top three findings are the ability to “distinguish information” (208; 61.4%) was the highest, followed by “judging issues based on facts” (198; 58.4%). However, the competency of “collecting and analyzing data” (139; 41.0%) was seen as intermediate competency level.

Sub-domain 3.2: Innovative thinking: This sub-domain has five competency statements: “Promoting the working environment” (169; 49.9%) was the highest. But the competencies “generating innovative solutions” (160; 47.2%) and “taking corrective measures” (154; 45.4%) were seen as intermediate levels of competency, as shown in Table 3.

Strategies for improving management competencies of Bhutanese PHC managers

This study also assessed 13 different strategies for improving the management competencies of Bhutanese PHC managers, described as follows: The majority of the respondents agreed that the following strategies can contribute to the competency development: Supervision and monitoring from the ministry (311; 91.8%); workshops (311; 91.7%); availability of standard operating procedure for work (302; 89.1%); regular supervision from the district levels (300; 88.5%); conducting periodic management meetings (300; 88.5%); continuing medical education (299; 88.2%); classroom-based short and long courses on ethics and leadership (291; 85.8%); conferences (285; 84.1%); attachment training (284; 83.8%); peer-to-peer coaching (276; 81.4%); coaching and mentoring (275; 81.1%); conduct on-the-job training (267; 78.8%); and research and publication (249; 73.4%), as shown in Table 4.

| Table 4 Strategies for improving management competencies of Bhutanese PHC managers in numbers and percentage (n=339) Abbreviation: PHC, primary health care. |

Discussion

This study identified the three management competency domains required for the Bhutanese PHC managers in reforming the DHS. The three domain competencies are “people”, “execution”, and “transformation”. In the context of Bhutanese PHC managers, the “people domain” was perceived to be the highest required competency, followed by “execution” and “transformation”. The NHCL model shows that the use of these domains captures the complexity and dynamic leadership and management qualities and competencies of the health managers to effectively demonstrate their roles.20

The current study confirmed seven key sub-domain management competencies required for the Bhutanese PHC managers, such as professionalism, relationship building, leadership, communication, managing change, analytical thinking, and innovative thinking. Among the seven sub-domain competencies, communication was perceived as highest, followed by professionalism and managing change. Studies conducted by Liang and Howard15 in 2010 and Liang et al16 in 2013 also found that communication, professionalism, and managing change are the most important competencies for health managers to perform tasks effectively.

The findings from this research are further validated by comparison with the findings and the evolution of required management competencies in other health systems, as described in Table 5. Bhutan PHC management competency findings are consistent with the findings of other international studies.

The current management competency levels of Bhutanese PHC managers in the identified domains were intermediate to competent in demonstrating their roles. The “people” domain was viewed as the most important and applicable to their current roles. The respondents perceived low competency level in demonstrating “execution” such as “translating vision and strategy into optimal organizational performance”.20 For the transformation domain, PHC managers had a low competency level for “demonstrating new models of health care leadership and management”. The reasons could be because the PHC managers did not receive adequate training in research and other training related to innovative and analytical thinking, which could broaden the intellectual capacity. These reasons indicate that a strategic focus is needed in the development of these competencies.

The current study found a gap between the levels of required competencies and the existing levels of competencies. In all three domains and the seven key sub-domains competencies, the PHC managers have intermediate levels of competencies, where the managers are expected to be competent or expert to perform their roles effectively.

This study identified that periodic supervision and monitoring from the ministry, capacity building workshops, a standard operating procedure for work, and regular supervision from the district levels were seen as the most predominant strategies for improving competencies of Bhutanese PHC managers. Briggs et al33 suggested that health managers need training and education to be effective in managing the health system. Egger et al34 indicated that the enabling working environment strategies such as availability of rules and guidelines under which they work and supervision from the higher levels are vital for improving management competencies.

Conclusion

The findings presented in this paper will help to increase an understanding of leadership and management competencies required by Bhutanese PHC managers. The identification of three competency domains and seven sub-domain competencies is a clear indication of the existence of leadership and management competencies in managing the DHS.

Limitations and future research

This study is based upon a process of self-assessment with all possible biases in relation to context based essential competencies for health managers. The findings of this study may not be generalized to other categories of health managers. Additional research is warranted to study other competencies required by the different management levels of PHC managers in Bhutan.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend sincere gratitude to the College of Health Systems Management, Naresuan University (CHSM NU), NU Thailand for the postgraduate studies scholarship. The authors would like to thank Mr Kevin Mark Roebl, Naresuan University Writing Editor for editing the language of this paper. The funding for data collection was supported by CHSM, NU Thailand.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting or revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Ministry of Health. National Health Policy of Bhutan. Ministry of Health, Thimphu, Bhutan; 2011. Available from: https://www.gnhc.gov.bt/en/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/nationalHpolicy.pdf. Accessed August 19, 2018. | ||

Wangmo T. Starting Strong on the SDGs in Asia: Readiness in Bhutan. Institute for Global Environmental Strategies; July 1, 2016; Japan. Available from: file:///C:/Users/admin/Downloads/Bhutan_readiness_final_for_print_2%20(6).pdf. Accessed on August 2, 2018. | ||

World Health Organization. Decentralization of health-care services in the south-east Asia region. Report of the regional seminar; 6–8 July 2010; Bandung, Indonesia. Available from: http://apps.searo.who.int/PDS_DOCS/B4638.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2018. | ||

Bureau NS. Population and Housing Census of Bhutan. Thimphu: Royal Government of Bhutan; 2017:1–288. | ||

Ministry of Health. Annual Health Bulletin. Thimphu, Bhutan: Minisrty of Health; 2017:1–123. | ||

Bhutan. The Constitution of the Kingdom of Bhutan. Thimphu: Royal Government of Bhutan; 2008:1–75. | ||

Yangchen S, Tobgay T, Melgaard B. Bhutanese health and the health care system: past, present, and future. Druk J. 2016. Available from: http://drukjournal.bt/bhutanese-health-and-the-health-care-system-past-present-and-future/. Accessed October 20, 2018. | ||

World Health Organization. Regional Workshop for Trainers on Sub-national/District Health Management Development: Report of the Workshop 22–25 April 2008; Bali, Indonesia. Available from: http://www.who.int/management/district/overall/SEARO_Regional_workshop_for_trainers.pdf. Accessed July 25, 2018. | ||

World Health Organization. Regional Workshop on Strengthening the Management Capacity of Health Managers at Sub-National/District level; 28 February – 2 March 2007; Jakarta, Indonesia. Available from: http://apps.searo.who.int/pds_docs/B0619.pdf. Accessed July 25, 2018. | ||

World Health Organization. The Kingdom of Bhutan Health System Review. Health Systems in Transition. Regional Office for South-East Asia. WHO, Geneva, New Delhi; 2017. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/25570. Accessed April 12, 2018. | ||

Sharma J, Zangpo K, Grundy J. Measuring universal health coverage: a three-dimensional composite approach from Bhutan. WHO South East Asia J Public Health. 2014;3(3):226–237. | ||

Combes JR, Arespacochaga E. Physician competencies for a 21st century health care system. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(3):401–405. | ||

Asian Development Bank. Bhutan: Health Care Reform Program. Asian Development Bank; 2006: 1–58. Available from: https://www.sabin.org/sites/sabin.org/files/restricted/ADB_Bhutantrustfundeval_33071-BHU-PCR_06.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2018. | ||

Dorros GL. Building Management Capacity to Rapidly Scale Up Health Services and Outcomes. World Health Organisation, Geneva; 2006. Available from: http://www.who.int/management/DorrosPaper020206.pdf. Accessed June 10, 2018. | ||

Liang Z, Howard PF. Competencies required by senior health executives in New South Wales, 1990–1999. Aust Health Rev. 2010;34(1):52. | ||

Liang Z, Howard PF, Koh LC, Leggat S. Competency requirements for middle and senior managers in community health services. Aust J Prim Health. 2013;19(3):256–263. | ||

Vriesendorp S, Shukla M, Lassner J.K. Health Systems in Action: An eHandbook for Leaders and Managers; 2010. Available from: http://www.lmgforhealth.org/sites/default/files/Health%20Systems%20in%20Action%20an%20eHandbook%20for%20Leaders%20and%20Managers_2.pdf. Accessed August 20, 2018. | ||

de Savigny D, Adam T. System Thinking for Health Systems Strengthening. World Health Organisation, Geneva; 2009. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44204/9789241563895_eng.pdf;jsessionid=7C6E51F8AF9E4A58A43EE8054C569931?sequence=1. Accessed August 23, 2018. | ||

Lekshmi P, Radhika R. Competency management as a strategy for performance appraisal. Int J Chem Pharmaceut Sci. 2016;9(4):1909–1912. | ||

National Center for healthcare Leadership. National center for healthcare leadership competency model: NHCL; 2005–2010. Available from: http://www.nchl.org/Documents/NavLink/Competency_Model-summary_uid31020101024281.pdf. Accessed June 13, 2018. | ||

Bartee RT, Winnail SD, Olsen SE, Diaz C, Blevens JA. Assessing Competencies of the Public Health Workforce in a Frontier State. Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2003:459. | ||

Royal Civil Service Commission of Bhutan. Managing For Excellence Max Manual. Thimphu: Royal Civil Service Commission; 2017. Available from: http://www.rcsc.gov.bt/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Final-MaX-Manual.pdf. Accessed August 15, 2018. | ||

Binkley M, Erstad O, Herman J, et al. Defining Twenty-First Century Skills. In: Griffin et al, editors. Assessment and Teaching of 21st Century Skills. Berlin: Springer Science+Business Media B.V.; 2012:17–66. | ||

American College of Healthcare Executive. American Healthcare Executive Competencies Assessment Tool. ACHE; 2018. Available from: https://www.ache.org/pdf/nonsecure/careers/competencies_booklet.pdf. Accessed August 19, 2018. | ||

Stefl ME. Common Competencies for All Healthcare Managers: The Healthcare Leadership Alliance Model. United States: Foundation of the American College of Healthcare; 2008:360. | ||

Australian College of Health Services Management. Master health service management competency framework. ACHSM; 2016. Available from: https://achsm.org.au/Documents/Education/Competency%20framework/2016_competency_framework_A4_full_brochure.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2018. | ||

Briggs DS, Smyth A, Anderson JA. In search of capable health managers: what is distinctive about health management and why does it matter? Asia Pacific J Health Manag. 2012;2:71. | ||

Leech NL, Onwuegbuzie AJ. A typology of mixed methods research designs. Qual Quant. 2009;43(2):265–275. | ||

Turner RC, Carlson L. Indexes of item-objective congruence for multidimensional items. Int J Test. 2003;3(2):163–171. | ||

Panayides P. Coefficient alpha: interpret with caution. Eur J Psychol. 2013;9(4):687–696. | ||

Cochran WG. Sampling Techniques. 3rd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons, c1977; 1977. | ||

Waleetorncheepsawat W, Asiraphot V. A study of attitude towards energy drinks in Thailand: a master thesis in business, Thailand, Bangkok; 2009. Available from: http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:225451/FULLTEXT01.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2018. | ||

Briggs DS, Fraser J, Campbell S, Tejativaddhana P, Cruickshank M. The Thai-Australian Health Alliance: developing health management capacity and sustainability for primary health care services. Educ Health Change Learn Pract. 2010;23(3). | ||

Egger D, Travis P, Dovlo D, Hawken L. Strengthening Management in Low-Income Countries. Making Health System Work. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. | ||

Dorji K. Leadership and Management Competencies Required for Bhutanese Primary Health Care Managers in Reforming the District Health System. A Master Thesis in Health Systems Management, Naresuan University, Thailand, Phitsanulok; 2018. |

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.