Back to Journals » Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare » Volume 12

Kuskaya: A training program for collaboration and innovation in global health

Authors Chan MC , Bayer AM, Zunt JR, Blas MM, Garcia PJ

Received 5 May 2018

Accepted for publication 14 August 2018

Published 27 December 2018 Volume 2019:12 Pages 31—42

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S173165

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Michelle C Chan,1 Angela M Bayer,1 Joseph R Zunt,2 Magaly M Blas,1 Patricia J Garcia1

1School of Public Health and Administration, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru; 2Departments of Neurology and Global Health, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

Abstract: To solve increasingly complex global health problems, health professionals must collaborate with professionals in non-health-related fields. The Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia and University of Washington created the NIH-funded Kuskaya training program in response to the need for transformative global health training for talented graduates from all disciplines. Kuskaya is a 1-year, interdisciplinary training program that teaches Peruvian and US graduates critical skills related to public health research through the design and implementation of a collaborative research project in Peru. Between 2014 and 2018, the program has trained 33 fellows, of which one third were from non-health disciplines. The program is unique because it targets junior trainees from disciplines outside of the health field, the program’s curriculum is adapted to fit the fellows’ backgrounds and professional aspirations, and the structure of the program allows for collaboration within the cohort and encourages fellows to apply for additional funding and pursue advanced degrees. Lessons learned in designing the Kuskaya program include: 1) involving mentors in the fellow selection process, 2) involving fellows in existing lines of research to increase mentor involvement, 3) institutionalizing mentoring through regular works-in-progress meetings and providing mentoring materials, and 4) defining a core curriculum for all fellows while providing additional supplementary materials to meet each cohort’s needs, and evaluating their progress. Kuskaya provides an innovative model for bi-national, global health training to engage and provide a public health career pathway for all professionals.

Keywords: public health, international health, program design, education

Introduction

Globalization has produced a heightened awareness of problems affecting population health that require the expertise and collaboration of multiple disciplines to effectively implement change.1–3 Although solving these problems is difficult, the formation of cross- and interdisciplinary collaborations between different disciplines, the private and public sectors as well as different levels of government, and thinking “outside of the box” can result in innovative tools, processes, and products to reduce the burden of disease throughout the world.4,5 A diverse range of professionals – from within and outside the health professions – are often involved in global health projects, with the global agenda becoming more focused on the development and implementation of innovative technologies such as point-of-care diagnostic tests6–8 or e-health.9–11 However, the literature rarely mentions global health research training for non-health professionals – with the exception of biomedical informatics training.12–15 Global health training programs vary in objectives, size, duration, intensity, and quality; however, interestingly, both global health and innovation literature emphasize the concepts of interdisciplinarity and teamwork,16–22 as well as mentoring23,24 – particularly in its practical application to real-world, complex, and global problems (Figure 1). The question remains: How do we broaden global health training to integrate participants from other disciplines?

To this end, herein, we share the experience of an innovative global health training program for young professionals from both health and other disciplines that was developed and implemented by the School of Public Health and Administration at the Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia (UPCH) in Lima, Peru, and the Department of Global Health at the University of Washington (UW) from 2013 to 2018. Kuskaya: an Interdisciplinary Training Program for Innovation in Global Health, supported by the Fogarty International Center of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH-Fogarty), offers an innovative, interdisciplinary, academic, and field-based program for talented graduates from health and non-health-related disciplines to think creatively about how to develop and implement interventions to address public health issues of critical importance for Peru and of strong relevance to other countries. Kuskaya means “working together” in Quechua – a native language of the Andes.

Prior global health training initiatives between UW and UPCH

Prior global health training initiatives between the UW and UPCH formed the foundation of the Kuskaya program’s key components, including a strong base of faculty mentors at both institutions, intentional matching of fellow pairs to include at least one from each institution from complementary disciplines, and efforts to continue promising lines of research over subsequent years through UPCH support. A Global Health Demonstration Program in Peru was awarded to UPCH by NIH-Fogarty and implemented between 2005 and 2012 at UPCH,22,25 which resulted in the development of a 5-year Bachelor’s and Master’s degree in Public Health and Global Health.26 In 2010, the UW and UPCH received a Framework Programs for Global Health Signature Innovations Initiative award funded by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. This award allowed us to pilot an interdisciplinary education, training, and mentoring program in Global Health leadership, policy, and management for postdoctoral fellows. Lessons learned from these research training initiatives were used to tailor a new program aimed to help build the next generation of global health leaders working together.

Fellow selection process

Fellowship applications were reviewed by the Fellow Selection Committee, comprised of the Program Directors and Program Coordinator of the Kuskaya program, and two faculty members from the UPCH. Applications were scored according to the synergy and relevance of the proposed research to the existing lines of research; the likelihood of academic success; and soft skills including leadership, teamwork, and flexibility; the most promising candidates were invited to interview with the Committee.

On average, we accepted one out of nine candidates. In total, 33 fellows were selected over the course of the program and 36 fellowships were offered; three fellowships were extended for a second year for exceptional fellows (Table 1).

| Table 1 Kuskaya fellowship call for applications for Peruvian and US candidates: the number of applications, candidates interviewed, and candidates accepted into the program |

The Kuskaya training program

The goal of the NIH-Fogarty-funded Kuskaya training program was to develop a new generation of innovative leaders in global health who are capable of working collaboratively with interdisciplinary teams of colleagues from the South and North to frame problems and develop creative, innovative solutions through research. Between 2014 and 2018, the Program offered 12-month fellowships to US and Peruvian residents and citizens to design and implement a global health research project in Peru. Fellow projects and experiences are summarized on the program website: www.kuskaya.org.

The Kuskaya training program is composed of four primary academic activities: 1) courses, 2) a mentored research project, 3) monthly events and seminars, and 4) interdisciplinary mentoring (Figure 2). To account for the diverse backgrounds and education levels of our trainees, flexibility was built into the training program through individual development plans, which were implemented during the program.

Courses

The Kuskaya courses are mandatory for all fellows and were implemented over the course of the fellowship. Intensive courses were placed at approximately months 1, 5, and 12 of the fellowship to combine both theoretical and practical learning, and to allow fellows to focus on key, time-consuming moments during the research project, including independent review board (IRB) protocol submission, fieldwork, and manuscript writing.

Advanced topics in global health (Month 1)

Daily classes during the first month of training provided a theoretical background for diverse issues related to global health and relevant tools to address these issues, with a focus on Peru. Topics included: Introduction to Global Health, Peruvian Health Systems, Social Determinants of Health, Implementation Research, Public Policy and Stakeholder Mapping, Social Business Models, Interculturality and Health, Qualitative and Quantitative Methods, Data Analysis, Epidemiology, Ethics in Research, and Leadership and Negotiation. In addition, this 1-month orientation included site visits to health establishments, public health organizations, and ongoing research projects.

Qualitative methods workshop (Month 5)

A 2-day workshop on qualitative methods was taught during Month 5 of the fellowship, when fellows were typically analyzing their results. The workshop included a theoretical component and hands-on practice sessions in qualitative analysis.

Scientific writing (Month 12)

In addition to mentor support, a virtual course on scientific writing was offered during Month 12 of training, which helped to fortify and refine the writing skills of fellows and assist with drafting their research articles. The Kuskaya training program evolved to adapt to each specific cohort’s needs; the scientific writing course was added in the fourth year of Kuskaya.

Research project

Research projects were the cornerstone of the Kuskaya fellowship. Under the guidance of mentors, fellows worked in US–Peruvian teams to design, implement, and, often, publish results from their projects over the 12 months of the fellowship. Research topics ranged from maternal and child health, neglected diseases, infectious diseases, land-use change and health, child development, domestic violence and alcohol use, architecture and health, and information and communication technologies. Table 2 includes a list of past and current research projects implemented by the fellows.

| Table 2 List of past and current research projects in the Kuskaya training program and corresponding articles, calls for proposals, and advanced degrees |

The training program and mentoring were crucial for successful implementation, as many of the Kuskaya fellows had little to no prior experience in research. Unlike many other training programs where trainees conduct analysis of secondary data, Kuskaya fellows were involved in the entire research cycle from development of the proposal to fieldwork, data analysis, and publication. Fieldwork allowed fellows to develop a set of new skills – planning, development, validation and implementation of instruments, negotiation, and working with local community leaders – which would not have been included in a secondary data analysis.

Events and seminars

Every month, Kuskaya hosted the “Innovations in Global Health Seminars” featuring a variety of global health topics: Health Technologies, Mentoring in Research, Child Development, Innovations in Global Health, Research Integrity and Responsible Conduct of Research, Clinical Research, Maternal and Child Health, Neglected Diseases, Gender and Health, Health Situation Analysis, Health in Vulnerable Communities, HIV and Resource-Limited Settings, and Environmental Health. The Innovations in Global Health Seminars is an important part of the Kuskaya training program, and serves the purpose of introducing the fellows and broader community to key global health topics and experts as well as connecting them to the larger research community in Peru. Moreover, these events showcase the research themes being explored by the fellows. Furthermore, we invited other researchers funded through the NIH-Fogarty International Center to present their projects, thereby promoting interactions between different research groups in Peru. The seminars were open to the public.

In addition, the Kuskaya training program organized symposiums or summits focused on research areas related to fellow research topics: climate change, One Health, and innovations in global health (Table 3).

| Table 3 Conferences, symposiums, and summits organized by the Kuskaya program between 2014 and 2017 Abbreviations: NGOs, nongovernmental organizations; UPCH, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia. |

Mentoring

Mentorship was a key component of the Kuskaya training program. Each Kuskaya research team had a mentorship team comprising two to four individuals who brought different, but complementary, strengths to the team and included individuals from US and international institutions. For each group, a “lead” mentor was identified who had the closest supervisory contact with the research team. Two months prior to the fellowship, fellows and their mentors discussed ideas for possible research projects through videoconferencing and, during the first week of training, fellows and mentors read through and signed a series of documents on mentoring, including a Mentoring Handbook, Compact Form, Encounter Form, and Checklist, which helped to establish expectations for the year. These expectations focused on personal and professional goals, frequency of meetings, and preferred mechanisms of communication. Mentors met with fellows at least twice each month and as frequently as several times a week, depending on fellow and project needs.

In addition, the Kuskaya research teams had monthly work-in-progress sessions with UW and UPCH Program directors and their mentors, during which they presented project advances and discussed the challenges they encountered.

Highlights from the Kuskaya training program

The Kuskaya training program differed from other training programs in that it was “South-led,” interdisciplinary, and trained both health and non-health professionals.

Primary awardee from an low- and middle-income country

Of the 35 grants awarded through the NIH-Fogarty’s Framework Programs for Global Health Innovation (FRAME Innovation), only three were awarded to non-US institutions, including the Kuskaya training program. In addition, of the current 10 FRAME Innovation grants, Kuskaya is the only grant awarded to a non-US institution. The implications of having a foreign institution as primary awardee include: lower salary requirements, which resulted in a higher number of fellows trained; and potentially more sustainable lines of research defined by the local, non-US institution.

Fellow characteristics: junior trainees from disciplines outside of traditional health disciplines

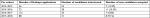

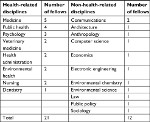

Fellows typically apply to this program to acquire skills in global health research either before or after obtaining a terminal degree (eg, PhD, MD, DVM, MBA, MSEng). Fellows came from a wide variety of disciplines, one third of which were unrelated to health (Table 4). From 2014 to 2018, we trained 33 fellows, with fellows almost equally distributed between undergraduate- and graduate-level individuals: 12 bachelors (nine Peruvian, three US), ten masters (five Peruvian, five US), three PhD students (all US), seven professional doctorates (all Peruvians), and one postdoctoral fellow (Peruvian).

| Table 4 Background of Kuskaya fellows: health related and non-health-related disciplines |

In Peru, it is still uncommon for people to pursue graduate studies. However, the Kuskaya fellowship not only provided an opportunity for talented graduates from other disciplines to become involved in a rigorous training program in public health research, but also connected fellows to other researchers from US and Peruvian higher education institutions. This resulted in 17 (51.5%) of our fellows pursuing advanced degrees or further studies in health science or public health during and after the Kuskaya fellowship.

Extending research training for exceptional fellows

Unlike other programs that end after a year, the Kuskaya fellowship allowed exceptional fellows to extend their training. Productive fellows were eligible to apply for an additional year of stipend and research support. If selected, they were also required to serve as a junior mentor to the incoming cohort, thereby benefitting both the program and the individual by building mentoring skills during the second year and providing additional support for incoming teams.

Identifying fellows from diverse disciplines: “diamonds in the rough”

To broaden recruitment across other disciplines, we engaged in intensive recruitment during a 4-month period each year to disseminate the Kuskaya call for applications to a diverse group of higher education institutions, professional accreditation institutions (eg, the Peruvian College of Medicine), and governmental institutions in Peru and the US. In November of each year, emails, letters, and flyers were sent to 17–45 institutions in Lima and outside the capital, inviting students and staff to apply to the Kuskaya fellowship. Furthermore, other institutions helped to disseminate the fellowship by posting physical flyers on campus and electronic flyers on websites and social media sites, which resulted in 25–43 posts on institutional websites and social media including the Peruvian Ministry of Health, Ministry of Education, National Council of Science, Technology and Technological Innovation, and professional associations (Association of Engineers of Peru, Peruvian College of Medicine, Peruvian College of Veterinary Medicine) and various universities.

Interdisciplinary training and collaboration beyond teams

The goal of Kuskaya was to develop a new generation of innovative leaders in global health and integrate knowledge to find solutions for global health problems through a cross-cultural, interdisciplinary problem-solving-based research experience. Except for the Ghana-Michigan Postdoctoral and Research Trainee Network-Investing in Innovation award to the University of Michigan,27 the other eight Frameworks awards focused on infectious diseases and clinical research.

Due to the interdisciplinary nature of the program, more experienced fellows were able to make important contributions to other projects as well as collaborate outside of their research team. For example, an economist and a veterinarian from different research groups decided to submit a proposal together in response to the “Bright Ideas” Request for Proposals (Ideas Audaces in Spanish) offered by the National Council of Science, Technology and Technological Innovation (CONCYTEC in Spanish).

Pilot grants leading to additional funding and degrees

The Kuskaya program provided seed funding for interdisciplinary pilot projects in global health. Fellows were encouraged to expand upon existing pilot projects and apply to additional funding sources.

The Kuskaya program has successfully nurtured trainees from diverse backgrounds to be independent researchers in public health. One example is Mariella Siña, a 2014 cohort Kuskaya fellow with a background in chemical engineering; she applied for funding from CONCYTEC for a proposal entitled “Implementing eco-efficient measures in households in Lima to reduce the environmental footprint” and was funded $50,000 USD. Renzo Calderón and Camila Gálvez, a physician and an architect, respectively, from the 2015–2016 cohort, were awarded funding for their proposal “Kuska-RumiWasi: New construction technologies for the prevention of vector-borne diseases” by the Peruvian Consortium of Universities. Neha Limaye, a 2016 cohort fellow, was a finalist in the call for “Saving Lives at Birth: A Grand Challenge for Development” with her application “Nuestras Historias: Evaluating the Impact of Community-Created Digital Stories to Motivate Healthy Pregnancy and Newborn Decisions in the Peruvian Amazon, A Cluster Randomized Trial.” This project received the “Best Practice in Public Management” award at a national competition in 2017.

Lessons learned and recommendations

Furthermore, it is important to discuss some of the challenges and lessons learned during the implementation of Kuskaya.

Time constraints for completing an original research project within a year

A year is quite short to implement an original project from scratch and in global health. Delays are to be expected, such as backlogs of IRB protocol reviews. The Kuskaya program encouraged fellows to communicate with their fellow pairs and mentoring team for 2 months before the official start date, which helped fellows to define a topic and review the literature before the US fellows arrived in Peru. Moreover, the program relied heavily on directors and mentors to help set a realistic timeframe and project scope in order to successfully complete the project within a year.

Finding the right mentors

Because some research projects involved new lines of research previously unexplored at both institutions, it was difficult, sometimes, to find the “right” mentors – that is, mentors who had expertise in the subject area, experience and disposition, and availability to guide the research group. Investing effort to train new mentors and discuss the expectations and role of mentorship within our institutions was vital to establishing successful interdisciplinary mentoring teams.

Creating a flexible training program

The criteria for Kuskaya fellows included completion of a bachelor’s degree, some prior experience in research, and being a good fit with the research project and mentoring team. However, the call for fellows was disseminated to many disciplines – law, engineering, health sciences, humanities, social science, architecture, economics, and communication – which meant that, each year, the cohort profile differed vastly in academic experience and level of education, professional experience, and diversity of disciplines. The program was designed to be flexible: providing a common foundation of basic knowledge in public health during the 1-month orientation and three supplemental intensive virtual courses for those who lacked public health training: 1) Introduction to Epidemiology, 2) How to Develop a Research Proposal, and 3) Introduction to Biostatistics, which were taken by one third of the fellows. In addition, the program implemented additional workshops throughout the fellowship year according to where fellows were in the research cycle. While the core components of the Kuskaya training program were maintained during all four years, however, the program added supplemental content to meet the academic and research needs of each individual cohort.

Ability to evaluate impact in meaningful ways

The program provided both academic coursework and hands-on training in implementing research projects; however, it was important to define measures of a successful training program. We decided to include traditional indicators, such as publications, success at obtaining additional funding, and evidence of professional development (new positions or degrees), which are tracked up to 20 years after involvement in the program.

The Kuskaya program has contributed to the body of scientific knowledge in various disciplines and public health as well as to professional development for trainees across public health and other disciplines. Very few of the fellows had publications before entering the program. Table 2 lists grant proposals submitted and graduate programs completed by the Kuskaya fellows; 12 of our fellows submitted grants, and another three were awarded additional funding. In addition, eight fellows are currently enrolled in a master’s or doctoral program, five completed a graduate program, two are in a residency program, and three have completed other fellowships.

Conclusion

Kuskaya: An Interdisciplinary Training Program for Innovation in Global Health represents an innovative and successful South-driven framework for global health training. Junior trainees from diverse disciplines conducted research in US–Peru pairs to develop and implement meaningful projects in Peru. Over the course of the year, they were guided by mentors, connected to research communities, and learned to collaborate with governmental institutions. Through participation in interactive and didactic courses, they acquired traditional skills in global health research and “soft skills” in leadership and negotiation. Overall, Kuskaya provided an innovative model for engaging, training, and inspiring young professionals from health and non-health-related disciplines to work together to address grand challenges in global health.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health under Kuskaya: an Interdisciplinary Training Program for Innovation in Global Health (award number D43TW009375). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Collins PY, Patel V, Joestl SS, et al. Grand challenges in global mental health. Nature. 2011;475(7354):27–30. | ||

Daar AS, Singer PA, Persad DL, et al. Grand challenges in chronic non-communicable diseases. Nature. 2007;450(7169):494–496. | ||

Varmus H, Klausner R, Zerhouni E, Acharya T, Daar AS, Singer PA. Public health. Grand Challenges in Global Health. Science. 2003;302(5644):398–399. | ||

Rittel HWJ, Webber MM. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 1973;4(2):155–169. | ||

Conklin J. Wicked problems and social complexity. In: Conklin J, editor. Dialogue Mapping: Building Shared Understanding of Wicked Problems. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 2006:3–40. | ||

Hu J, Wang S, Wang L, et al. Advances in paper-based point-of-care diagnostics. Biosens Bioelectron. 2014;54:585–597. | ||

Myers FB, Lee LP. Innovations in optical microfluidic technologies for point-of-care diagnostics. Lab Chip. 2008;8(12):2015–2031. | ||

Yager P, Domingo GJ, Gerdes J. Point-of-care diagnostics for global health. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2008;10:107–144. | ||

Bernabe-Ortiz A, Curioso WH, Gonzales MA, et al. Handheld computers for self-administered sensitive data collection: a comparative study in Peru. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2008;8(1):11. | ||

Gerber T, Olazabal V, Brown K, Pablos-Mendez A. An agenda for action on global e-health. Health Aff. 2010;29(2):233–236. | ||

Lewis T, Synowiec C, Lagomarsino G, Schweitzer J. E-health in low- and middle-income countries: findings from the Center for Health Market Innovations. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90(5):332–340. | ||

Blas MM, Curioso WH, Garcia PJ, et al. Training the biomedical informatics workforce in Latin America: results of a needs assessment. BMJ Open. 2011;1(2):e000233. | ||

Curioso WH, Hansen JR, Centurion-Lara A, et al. Evaluation of a joint Bioinformatics and Medical Informatics international course in Peru. BMC Med Educ. 2008;8:1. | ||

Curioso WH, Fuller S, Garcia PJ, Holmes KK, Kimball AM. Ten years of international collaboration in biomedical informatics and beyond: the AMAUTA program in Peru. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2010;17(4):477–480. | ||

Kimball AM, Curioso WH, Arima Y, et al. Developing capacity in health informatics in a resource poor setting: lessons from Peru. Hum Resour Health. 2009;7(1):80. | ||

Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 2010;376(9756):1923–1958. | ||

García PJ. Repensando la educación de los profesionales de salud del siglo XXI: cambios y acciones en un mundo global. [Rethinking the education of XXI century health professionals: changes and actions in a global world. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2011;28(2):390–399. Spanish. | ||

Choi BCK, Pak AWP. Multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity in health research, services, education and policy: 1. Definitions, objectives, and evidence of effectiveness. Clin Invest Med. 2006;29(6):351–364. | ||

Finch TH, Chae SR, Shafaee MN, et al. Role of students in global health delivery. Mt Sinai J Med. 2011;78(3):373–381. | ||

Rowson M, Willott C, Hughes R, et al. Conceptualising global health: theoretical issues and their relevance for teaching. Global Health. 2012;8(1):36. | ||

Grand Challenges Canada/Grand Défis Canada, “Integrated Innovation”. 2010. Available from: https://www.grandchallenges.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/integratedinnovation_EN.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2018. | ||

Curioso WH, Lazo-Escalante M, Gotuzzo E, et al. Entrenando a la nueva generación de estudiantes en salud global en una universidad peruana. [Training the new generation of students in global health at a Peruvian university]. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2008;25(3):269–273. Spanish. | ||

Shah SK, Nodell B, Montano SM, Behrens C, Zunt JR. Clinical research and global health: mentoring the next generation of health care students. Glob Public Health. 2011;6(3):234–246. | ||

Cho DB, Cole D, Simiyu K, Luong W, Neufeld V. Mentoring, training and support to global health innovators: a scoping review. Glob J Health Sci. 2013;5(5):162. | ||

Garcia PJ, Curioso WH, Lazo-Escalante M, Gilman RH, Gotuzzo E. Global health training is not only a developed-country duty. J Public Health Policy. 2009;30(2):250–252. | ||

Garcia P, Armstrong R, Zaman MH. Models of education in medicine, public health, and engineering. Science. 2014;345(6202):1281–1283. | ||

Calys-Tagoe BNL, Clarke E, Robins T, Basu N. A comparison of licensed and un-licensed artisanal and small-scale gold miners (ASGM) in terms of socio-demographics, work profiles, and injury rates. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):862. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.