Back to Journals » International Journal of Women's Health » Volume 12

Knowledge of Neonatal Danger Signs and Associated Factors Among Mothers of <6 Months Old Child in Dire Dawa, Ethiopia: A Community Based Cross-Sectional Study

Authors Guta A , Sema A, Amsalu B, Sintayehu Y

Received 20 May 2020

Accepted for publication 30 June 2020

Published 24 July 2020 Volume 2020:12 Pages 539—548

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S263016

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Elie Al-Chaer

Alemu Guta,1 Alekaw Sema,1 Bezabih Amsalu,1 Yitagesu Sintayehu2

1Department of Midwifery, College of Medicine and Health Science, Dire Dawa University, Dire Dawa, Ethiopia; 2School of Nursing and Midwifery, College of Health and Medical Sciences, Haramaya University, Harar, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Yitagesu Sintayehu Tel +251913276896

Email [email protected]

Introduction: Neonatal mortality is one of the challenging issues in current global health. Globally, about 2.5 million children die in the first month of life, out of which Sub-Saharan Africa accounts > 40% per annual. Currently, the neonatal mortality rate in Ethiopia is 30/1000 live births. In the study area, there was a limitation of data on mothers’ knowledge towards neonatal danger signs. Therefore, this study aimed to assess mothers’ knowledge of neonatal danger signs and associated factors.

Patients and Methods: A community-based cross-sectional design study was conducted in Dire Dawa from March 01/2019 to April 30/2019. Data were collected from 699 randomly selected mothers through a face-to-face interview. Bivariate logistic regression with p-value < 0.25 was entered into the multivariable logistic regression analysis. Finally, AOR with 95% confidence intervals at P-value < 0.05 was considered a significant association with the outcome variable.

Results: About 285 (40.8%) (95% CI: 37.3– 44.3) of mothers had good knowledge of neonatal danger signs, and 97.1% (95% CI: 94.1, 99.3) of mothers sought medical care at a health facility. Mothers who were governmental employed (AOR = 2.14, 95% CI: 1.17– 3.9), whose fathers’ educational level is secondary or above (AOR=2.3, 95% CI: 1.18– 4.49), four/more antenatal care visit (AOR=4.3, 95% CI: 1.5– 12.3), whose baby developed danger signs (AOR=3.5, 95% CI: 2.13– 5.73), and those mothers received education on neonatal danger sign (AOR=7, 95% CI: 4.2– 11.5), had a significant association with knowledge of neonatal danger signs.

Conclusion: Maternal knowledge toward neonatal danger signs was low and a high number of mothers sought medical care at a health facility. Mother’s occupation, fathers’ education, development of neonatal danger signs, frequency of antenatal care visit, and received health education on neonatal danger signs were factors associated with mothers’ knowledge towards neonatal danger signs.

Keywords: neonatal danger signs, knowledge, healthcare-seeking, Dire Dawa

Introduction

Danger signs in the neonatal period (0–28 days) are non-specific and that indicates severe illness. Neonatal Danger Signs (NDSs) are signs used in integrated management of neonatal and child illness (IMNCI) by practitioners to identify children who need medical care.1 Newborn danger signs refer to the presence of clinical signs that would indicate a high risk of neonatal morbidity and mortality and the need for early therapeutic intervention. Which includes, cough, difficult/fast breathing, lethargy, loss of consciousness, convulsion, fever, hypothermia, poor feeding or unable to suckle, persistent vomiting, diarrhea, yellow palms or soles or eyes, eye discharge/redness, and discharge or pus from the umbilicus.2

According to World Health Organization (WHO) facts sheet globally, 5.3 million of under-five children death occurred, out of which nearly half 2.5 million children died in the first 28 days of life, 7000 neonatal deaths every day in 2018; out of which 40% of neonatal deaths occurred in Sub-Saharan Africa. Half of all under-five deaths occurred in just five countries including Ethiopia, and the other India, Nigeria, Pakistan, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Therefore, effective strategies to improve newborn survival in developing countries require a clear understanding of the patterns and determinants of newborn-care seeking by mothers, families and other newborn caregiver.3

Improving families’ care-seeking behavior is one of the important strategies to reduce child death in developing nations. The WHO estimates that seeking prompt and appropriate care could reduce child mortality due to acute respiratory infections by 20%.4 An important method to reduce newborn death is early recognition of NDSs and the provision of quality of curative health services for sick newborns.5 Early detection of newborn morbidity could contribute significantly to increase child survival.6 According to WHO, children face the highest risk of dying in their first 28 days of life at an average global rate of 18 deaths per 1000 live births in 2018. Three-quarter of neonatal mortality, occur in the first seven days of life and 1/3rd dying on the first day.7

The first four weeks of life is the time, which the highest risk of newborn death occurs. It is thus crucial that appropriate feeding and care provided during this period, both to improve the child’s chances of survival and to lay the foundation for a healthy life.8 NDSs is one of the most common causes of neonatal mortality in developing nations. There are some views that current effort at reducing neonatal mortality is hindered by poor understanding of the social determinants of health as well as danger signs of the neonate and putting into place appropriate strategies to reduce its impact.9 The highest prevalence of neonatal mortality occurs at home, where a few mothers seek medical care for signs of neonatal illness, and nearly no newborn is taken to health facilities when they are sick. Delayed healthcare-seeking can contribute to neonatal mortality.10 Understanding the care-seeking behavior minimizes potential delays and effectively improve newborns health.11

In Ethiopia there are 2.4 million births per year, however, the magnitude of death is very high; 1500 under-fives die/day, 210,000 infants die per year, and 350,000 die before they reach their 5th year.12 According to the mini Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey 2019, Neonatal Mortality Rate (NMR) is 30 per 1000 live births. Infant mortality rate (IMR) is 43 deaths per 1000 live births and under-five mortality is 55 deaths per 1000 live births.13

Millions of mothers and their newborns throughout the world are living in a social environment that does not encourage healthcare-seeking behavior. Thus, many mothers do not generally seek formal healthcare during the postpartum, which has a major impact on healthcare-seeking for mothers and the survival of their newborn.14

Studies in Ethiopia, low maternal knowledge about NDSs, indicate that nearly 80% of mothers were more likely to delay in deciding to seek care, which responsible for increased neonatal mortality a key entry point to improve neonatal health. This could intern increases the morbidity and mortality of the child.15 Early recognition of NDSs has been linked to improved neonatal outcomes and a decrease in mortality.16 Since there is high home delivery or discharged from the health facility early, families should be able to know signs of newborn illnesses and bring the newborn infant to the health facilities. However, studies in this study area were limited. Therefore, this study aimed to assess mothers’ knowledge of NDSs and associated factors, and gaps in mothers’ knowledge were identified, which can help as base-line information for the concerned bodies.

Patients and Methods

Study Setting and Period

The study was conducted from March 1st, 2019 - April 30, 2019, in Dire Dawa administrative city, which is 515 km away from the capital city, Addis Ababa to the East. The city has an estimated 506,936 total population, which consists of 248,298 males and 258,638 females. It has 2 public hospitals and 15 public health centers.

Study Design and Participants

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted among randomly selected women who have a child aged less than 6 months residing in the selected Kebeles of Dire Dawa town were included. The mothers who could not communicate due to illness and who were not available at home during data the collection period after three visits were excluded from the study.

Sample Size and Sampling Procedure

The sample size was obtained by using single population proportion formula using a p-value 18.2% from the previous study finding of mothers’ knowledge about NDSs,15 95% CI, a margin of error= 0.03, and 10% non-response rate. Then, the final sample size was 699 participants. First, 5 Kebeles out of 9 Kebeles of Dire Dawa town were selected by using simple random sampling procedure. A systematic random sampling technique was used to select 699 study subjects by using the sampling frame (list of house-hold with women who had a child aged less than 6 months in each Kebeles) was obtained from the health extension worker. The number of respondents was proportionally allocated per the total number of children in the sampling of the selected Kebele and data was collected every 3rd interval, by using those Kebeles with the total number of children aged less than 6 months [Kebele 01 (640), Kebele 02 (703), Kebele 04 (334), Kebele 06 (266) and Kebele 09 (281)].

Data Collection Instrument, Procedure and Quality Assurance

Data were collected by face-to-face interviews using structured, pre-tested, and adapted based on different kinds of literature, which includes different parts: first, socio-demographic profiles, knowledge on NDSs, mother’s healthcare-seeking practices on NDSs, and mother’s healthcare utilization and obstetric conditions.15,17-20 First, we prepared in English, and then translated to the local language and back to English by another translator to check the consistency of the tool. Ten diploma midwives did the data collections. Two masters of public health holders and investigators supervised the data collection process daily.

The quality of data was assured by pre-testing of data collection tools on 10% (70) of mothers in other sites than the selected Kebeles before the main data collection took place, and corrections on the instrument were made accordingly. Two days of training had been given for supervisors and data collectors before data collection. Regarding the training, the emphasis was given on purposes of the study, the significance and appropriate meanings of each question as well as on the ethical issue. Each data collector checked the questionnaires for completeness before visiting the next participants. Every day, supervisors and the investigators reviewed each questionnaire for completeness. The necessary feedback was offered to data collectors in every morning.

Measurement and Definitions

The dependent variable is mothers’ knowledge toward neonatal danger signs (Good/poor). The independent variables include mothers age, mothers religion, ethnicity, marital status, mothers educational level, mothers occupation, fathers’ educational status, sex of the infant, neonates development of danger signs, numbers of parity, Antenatal Care (ANC) follow up during current pregnancy, frequency of ANC visit, place of delivery, assistance during labor, Postnatal Care (PNC) attendant, frequency of the PNC visit, and mothers receiving education about NDSs and neonate health from a health professional.

Newborn danger signs refer to the presence of clinical signs that would indicate a high risk of neonatal morbidity and mortality and the need for early therapeutic intervention. Which includes, cough, difficult/fast breathing, lethargy, loss of consciousness, convulsion, fever, hypothermia, poor feeding or unable to suckle, persistent vomiting, diarrhea, yellow palms or soles or eyes, eye discharge/redness, and discharge or pus from the umbilicus.2

Good knowledge is determined by if mothers mentioned three and above NDSs and Poor knowledge is determined by if mothers listed less than three of NDSs of WHO listed NDSs.15,17,21-23

Healthcare seeking practice is seeking medical or non-medical care in response to NDSs to reduce severity and complication after recognizing the NDSs and perceived nature of the illness. Data was distributed into two further categories, appropriate healthcare-seeking are those mothers who were taken their child to the registered health facilities (government or private health facility) after their baby’s developed danger signs and inappropriate healthcare-seeking are those who sought the care other than that.24

Data Processing and Analysis

Data were entered into the computer by using Epi data version 3.1. Data analysis was done by using SPSS software Version 21. Frequencies of variables were generated; tabulation and percentages were used to illustrate study findings. Pearson correlation test was done to see the relationship between variables. The association between the outcome variables and independent variables was analyzed using a logistic regression model. The variables that showed p <0.25 in the bivariate analysis were considered as a candidate for multivariable logistic regression analysis; this was to control all possible confounders and to detect associated factors of good knowledge towards neonatal danger signs. Hosmer and Lemeshow’s goodness-of-fit test was used to assess whether the necessary assumptions were fulfilled. The direction and the strength of statistical associations were measured by the odds ratio with 95% CI. AOR with 95% CI at P-value <0.05 was considered as a statistically significant association with knowledge of neonatal danger signs.

Ethical Consideration

Ethical clearance was obtained from the office of director for research and technology transfer of Dire Dawa University (approval number: DDU/RTI/6075/219). Permission letters were received from the Dire Dawa City administration Health office. The data was collected from each participant after obtaining informed, voluntary, written, and signed consent before the start of data collection, which was approved by the ethics committee after clearly explaining the purpose and importance of the study. Individuals were informed that it was fully voluntary, they could withdraw from the study at any time or refuse to answer, could ask anything about the study and that would not affect them. They were also informed that they would not receive any monetary incentive for participating in the study. All personal information was de-identified and kept separately, so every effort was made to maintain confidentiality throughout the study period and afterward. Furthermore, this study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics

The total calculated sampled 699 (100%) of mothers were interviewed. The mean age of the mothers was 28.27 years (St.D ± 4.84). The majority, 496 (62.8%), and 651 (93.1%) of the participants were aged 25–34 years and currently married respectively (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Distribution of Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Mothers Who Have a Child Less Than 6 Months Old in Dire Dawa, Eastern Ethiopia., 2018 (n=699) |

Mothers’ Knowledge About Neonatal Danger Signs

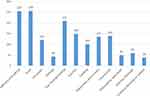

Two hundred eighty-five (40.8%), (95% CI: 37.3–44.3) of mothers had good knowledge of NDSs. The major sources of information for mothers were health professionals 422 (60.4%) followed by mass media 127 (18.1%), neighborhood 51 (7.3%), 17 (2.4%) from friends, and 21 (3%) from literatures. The types of media used were television 109 (15.6%) and radio 68 (9.7%). From the total respondents, 456 (60.9%) mothers mentioned at least one NDS. Two hundred fifty-eight (36.6%) of the mothers mentioned NDSs were fever (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1 Distribution of mentioned neonatal danger signs among mothers who have a child aged less than 6 months in Dire Dawa, Eastern Ethiopia, 2018 (n=699). |

Mother’s Newborn Care Practice

Six hundred fourteen (87.8%) of the mothers gave breast-feeding for their current neonate within 1 hour of delivery and, 58 (84%) of mothers gave bath for their neonate after 24 hours of delivery. Regarding cord care practice, nearly 3/4th 505 (72.2%) of mothers did not apply any substance to their infant cord. However, 194 (27.8%) of mothers applied a different substance to their infant cord: 159 (22.7%) butter and 35 (5.1%) other remedies. Five hundred eighty-four (83.5%) of mothers did not give pre-lacteal food for their neonate, 115 (16.5%) of mothers gave different pre-lacteal foods: 74 (10.6%) gave water, 22 (3.1%) gave spiritual water, and 19 (2.7%) gave other pre-lacteal food for their infant.

Mother’s Healthcare-Seeking Practices

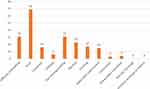

Of the total mothers, only 136 (19.7%) (95% CI: 16.5–22.6) of them observed at least one of the NDSs with their infant. Of these, Sixty-nine (50.7%) of the mothers observed fever with their neonate. Among those whom their neonate developed danger signs, 97.1% (95% CI: 94.1, 99.3) of them sought medical care at a health facility (i.e., 84 (61.8%) sought immediately and 48 (35.3%) sought for their infant after it gets worsened). Only, the rest 4 (2.9%) did not seek medical care (give home remedies, taken to traditional healer). Regarding the medical place, 62 (45.6%) of them sought medical at the governmental health center followed by a government hospital, private hospital and private clinic were 44 (32.4%), 22 (16.2%), and 4 (2.9%) respectively. The time-lapse between the occurrence of the NDSs and seeking the help of the medical care was (10.27±11.3 hours) (Figure 2).

|

Figure 2 Distribution of developed neonatal danger signs by their child among mothers who have a child aged less than 6 months in Dire Dawa, Eastern Ethiopia, 2018 (n=699). |

Mothers Healthcare Utilization and Obstetric Conditions

Four hundred sixty (65.8%) of the mothers were multipara. Six hundred thirty-three (91.1%) of them had ANC follow-up, 637 (91.1%) of them gave birth at health institutions and all of those gave birth at health institutions had at least one PNC follow-ups visit (with in the 1st 6 hours of delivery). Greater than half 388 (55.5%) of the mothers received health education from the health professional about NDS and health of neonates (Table 2).

|

Table 2 Maternal Health Care Services Utilizations and Obstetric Condition of Mothers Who Have a Child Less Than 6 Months in Dire Dawa, Eastern Ethiopia, 2018 (n=699) |

Factors Associated with Maternal Knowledge of Neonatal Danger Signs

In this study, nine variables are significant in bivariate (p-value <0.25), and of these, 5 variables are significantly associated with mothers’ knowledge on NDS by multiple logistic regression (p-value <0.05). These 5 main factors include: mother’s occupation, fathers’ education level, mothers of babies developed neonatal danger sign, ANC visit during last pregnancy, and received health education on neonatal danger sign and health of neonate.

Mothers’ occupation was factor significantly associated with mother knowledge on neonatal danger signs. Government employee mothers were 2 times [(AOR = 2.14, 95% CI: 1.17–3.9)] more likely to have good knowledge than those who were housewife, and those mothers who attended ANC four visit and more were 4.3 times [(AOR=4.3 95% CI 1.5–12.3)] more likely to have good knowledge than those mothers who had not attended ANC during the last pregnancy. This study indicated that fathers’ educational level was a significant predictor’ of mother knowledge on neonatal danger signs. Those fathers whose educational level was secondary and above education were 2.3 times [(AOR=2.3 95% CI 1.18–4.49)] more likely to have good knowledge as compared to fathers not educated. Another, those mothers whose infant developed danger signs were 3.5 times [(AOR=3.5 95% CI 2.13–5.73)] more likely to have good knowledge than those whose did not, and those mothers who had received education on neonatal danger sign from health professionals were 7 times [(AOR=7 95% CI 4.2–11.5)] more likely to have good knowledge as compared to their counterparts (Table 3).

|

Table 3 Factors Associated with Mother’s Knowledge About Neonatal Danger Signs of Mothers Who Have a Child Less Than 6 Months Old in Dire Dawa, Eastern Ethiopia, 2018 (n=699) |

Discussion

In this study, prevalence of good knowledge (mothers who mentioned at least three neonatal-danger signs) was 40.8% (95% CI: 37.3–44.3). This finding is in line with the studies conducted in India (39%) and Arba Minch, Ethiopia (40.9%).25,26 However, it is higher than the studies conducted in the North West Amhara region, Ethiopia (18.2%), Kenya (15.5%), four regions of Ethiopia (29.3%), Ambo town, Ethiopia (20.3%), and Nepal (26.7%).15,18,21,27,28 This discrepancy might be because of the study year since our study was conducted after those studies, which leads to mothers to get more information than before. Also, the previous study in 4 regions (Oromia, Tigray, Amhara, and SNNR) included mothers in a rural area. Again, we used a large sample size. However, this is lower than the studies conducted in Mekele (50.6%), Nigeria 78.3%, Wolkite Town, Gurage Zone (68.68%), Egypt (69%), Debre Tabor (61.70%) and Fogera District (64.1%).17,19,22,29–31 The possible reason might be a small sample size in the previous study; especially, studies in Mekele and Debre Tabor were an institutional-based study that all respondents gave birth at the health institution.

Regarding the healthcare-seeking practice, 97.1% of whose infant developed danger signs sought medical care at the health institution. This is higher than the studies conducted in Tenta District, (41.3%) and Wolkite, (32%), Ambo town (79.2%).17,24,27 The discrepancy might be because there is better health coverage in the current study area and they are near to the center for care-seeking than those studies.

In our study, government employee mothers were 2 times more likely to have good knowledge of NDSs than those who were housewives (AOR = 2.14, 95% CI: 1.17, 3.9). The possible reason might be those governmental employed mothers are well-educated and more seeking healthcare and, they might be using a different source of health-related information. The father’s educational level is also associated with mothers’ knowledge; those whose spouse education level was secondary and above were two times knowledgeable compared to whose did not attend formal education (AOR = 2.3, 95% CI:1.18, 4.49). The results of our study supported the previous study done in Addis Ababa.20 The reason might be because as fathers are educated, the family easily access health-related information and they also seek healthcare from a health facility (they have a great chance to meet health professionals and access information on NDSs than that of non-educated.

Mothers whose neonate developed danger signs were 3.5 times more likely to have good knowledge than those who did not (AOR = 3.5, 95% CI: 2.13, 5.73). This finding agreed with a study done in Ambo town, which was three-fold increased odds compared to their counterparts.27 The possible reason might be those mothers whose infant developed NDSs were more likely to seek care from a health facility that led mothers to easily access information toward neonatal health.

In the present study, those mothers who attended ANC four visits and more were 4.3 times more likely to have good knowledge than those who had not attended ANC during the last pregnancy (AOR = 4.3, 95% CI: 1.5, 12.3). This is similar to the results of the study done in North West Amhara, Ethiopia, and rural Uganda.15,32 The reason might be when ANC increase the mother’s linkage with health professional which increases the access of information, related to NDSs.

In this study, the result also showed that mothers who had received NDSs information from health professionals were 7 times more likely to have good knowledge as compared to their counterparts (AOR = 7, 95% CI: 4.2, 11.5). This finding is congruent with the studies conducted in Ambo town and Debre Tabor.27,30 The reason might be those mothers who had information from health professionals helps them to stick to the information related to their children’s health status.

Limitation

Though the study response rate is 100%, and tried to address knowledge on NDSs and care-seeking practice of mothers who have a child aged less than 6 months it is not free of recall bias because all mothers were interviewed for the content of their baby aged before 28 days of life.

Conclusion

Maternal knowledge about NDSs was low and a high number of mothers sought medical care at a health facility for their sick neonate. Factors associated with the mother’s knowledge towards NDSs were mother’s occupation, father education status, whose infant developed danger sign, frequency of ANC visit, and mothers who received health education on NDSs. It is advisable that improving fathers’ education, making employment accessible to mothers and supporting pregnant mothers to attend ANC at the recommended frequencies, and the healthcare providers need to educate mothers on NDSs during the mothers’ hospital visit.

Abbreviations

ANC, Antenatal Care; NDSs, Neonatal Danger Signs; PNC, Postnatal Care; WHO, World Health Organization.

Data Sharing Statement

All related data has been presented within the manuscript. The data set supporting the conclusions of this article is available from the corresponding Author (Yitagesu Sintayehu) upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgment

First and for most, we would like to thanks Dire Dawa University Research and Technology Interchange and the College of Medicine and Health Sciences for providing us with the opportunity to conduct this research. Secondly, we would like to thanks all data collectors and supervisors for their valuable contribution by collecting and facilitating data collection. Also, we would like to thanks study participants to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreed to submit to the current journal; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Baqui AH, Rahman M, Zaman K, et al. A population-based study of hospital admission incidence rate and bacterial etiology of acute lower respiratory infections in children aged less than five years in Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr. 2007;25(2):179–188.

2. Young Infants Clinical Signs Study Group. Clinical signs that predict severe illness in children under age 2 months: a multicentre study. Lancet. 2008;371(9607):135–142. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)6006-3

3. Syed U, Khadka N, Khan A, Wall S. Care-seeking practices in South Asia: using formative research to design program interventions to save newborn lives. J Perinatol. 2008;28(S2):S9–S13. doi:10.1038/jp.2008.165

4. World Health Organization. Technical Bases for the WHO Recommendations on the Management of Pneumonia in Children at First-Level Health Facilities. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1991. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/61199/WHO_ARI_91.20.pdf.

5. Mathur N. Status of newborns in India. J Neonatol. 2005;19(1). Available from: http://www.indianjournals.com/ijor.aspx?target=ijor:jn&volume=19&issue=1&article=001. Accessed July 1, 2020.

6. Choi Y, El Arifeen S, Mannan I, et al.; Projahnmo Study Group. Can mothers recognize neonatal illness correctly? Comparison of maternal report and assessment by community health workers in rural Bangladesh. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15(6):743–753. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02532.x

7. World Health Organization (WHO). Newborns: reducing mortality. September 19, 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/newborns-reducing-mortality.

8. Graves MF. The Vocabulary Book: Learning and Instruction. Teachers College Press; 2016.

9. Hoque MM, Khan MFH, Begum JA, Chowdhury MA, Persson LA. Newborn care practices by the mother care givers and their knowledge about signs of sickness of neonates. Bangladesh J Child Health. 2011;35(3):90–96. doi:10.3329/bjch.v35i3.10497

10. Anyanwu FC, Okeke SR. Health care, care provider, and client satisfaction: transforming health care delivery system for improved health care seeking behaviour. J Mod Edu Rev. 2014;4(10):846–853. doi:10.15341/jmer(2155-7993)/10.04.2014/014

11. Mrisho M, Schellenberg D, Manzi F, et al. Neonatal deaths in rural southern Tanzania: care-seeking and causes of death. ISRN Pediatr. 2012;2012:1–8. doi:10.5402/2012/953401

12. Addisse M Maternal and child health care. Lecture notes for health science students Ethiopian public health training initiative. 2003. Available from: https://www.dphu.org/uploads/attachements/books/books_5455_0.pdf.

13. Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI) [Ethiopia] and ICF. 2019. Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey 2019: Key Indicators. Rockville, Maryland, USA: EPHI and ICF; Available from: https://www.unicef.org/ethiopia/reports/2019-ethiopia-mini-demographic-and-health-survey.

14. Herbert HK, Lee AC, Chandran A, Rudan I, Baqui AH. Care seeking for neonatal illness in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2012;9:3. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001183

15. Nigatu SG, Worku AG, Dadi AF. Level of mother’s knowledge about neonatal danger signs and associated factors in North West of Ethiopia: a community-based study. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8(1):309. doi:10.1186/s13104-015-1278-6

16. Gathoni A, Nduati R, Were F Mother’s knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding neonatal illness and assessment of neonates at Kenyatta National Hospital [University Of Nairobi M MED Dissertation]. Pediatrics and Child Health; 2013.

17. Anmut W, Fekecha B, Demeke T. Mother’s knowledge and practice about neonatal danger signs and associated factors in Wolkite Town, Gurage Zone, SNNPR, Ethiopia, 2017. J Biomed Sci. 2017;6(4). doi:10.4172/2254-609x.100077

18. Kibaru EG, Otara AM. Knowledge of neonatal danger signs among mothers attending well-baby clinic in Nakuru Central District, Kenya: cross-sectional descriptive study. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9(1):481. doi:10.1186/s13104-016-2272-3

19. Ekwochi U, Ndu IK, Osuorah CD, et al. Knowledge of danger signs in newborns and health-seeking practices of mothers and care givers in Enugu state, South-East Nigeria. Ital J Pediatr. 2015;41(1):18. doi:10.1186/s13052-015-0127-5

20. Mulatu F. Assessment of knowledge and health care seeking behavior about neonatal danger signs among mothers visiting immunization unit in selected Governmental Health Centers [Thesis AAU]. ADDIS Ababa, Ethiopia. 2012. Available from: http://localhost/xmlui/handle/123456789/7063.

21. Callaghan-Koru JA, Seifu A, Tholandi M, et al. Newborn care practices at home and in health facilities in 4 regions of Ethiopia. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13(1):198. doi:10.1186/1471-2431-13-198

22. Adem N, Berhe K, Tesfay Y. Awareness and associated factors towards neonatal danger signs among Mothers Attending Public Health Institutions of Mekelle City, Tigray, Ethiopia, 2015. J Child Adolesc Behav. 2017;5(06):365. doi:10.4172/2375-4494.1000365

23. Hadush A, Kassa M, Kidanu K, Tilahun W. Assessment of knowledge and practice of neonatal care among post natal mothers attending in Ayder and Mekelle Hospital in Mekelle, Tigray, Ethiopia 2013. SMU Medical Journal. 2016;3(1):509–525.

24. Molla G, Gonie A, Belachew T, Admasu B. Health care-seeking behavior on neonatal danger signs among mothers in Tenta District, Northeast Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. J Nurs Midwifery. 2017;9(7):85–93. doi:10.5897/IJNM2017.0266

25. Awasthi S, Verma T, Agarwal M. Danger signs of neonatal illnesses: perceptions of caregivers and health workers in northern India. B World Health Organ. 2006;84:819–826. Available from: https://www.scielosp.org/article/bwho/2006.v84n10/819-826/en/. Accessed July 1, 2020.

26. Degefa N, Diriba K, Girma T, et al. Knowledge about neonatal danger signs and associated factors among mothers attending immunization clinic at Arba Minch General Hospital, Southern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:1–8. doi:10.1155/2019/9180314

27. Bulto GA, Fekene DB, Moti BE, Demissie GA, Daka KB. Knowledge of neonatal danger signs, care-seeking practice and associated factors among postpartum mothers at public health facilities in Ambo town, Central Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12(1):549. doi:10.1186/s13104-019-4583-7

28. Tuladhar S. The determinants of good newborn care practices in the rural areas of Nepal. 2010. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/10092/5061.

29. Essa R, Akl O, Mamdouh H. Factors associated with maternal knowledge of newborn care among postnatal mothers attending a rural and an urban hospital in Egypt. J High Inst Public Health. 2010;40(2):348–367. doi:10.21608/jhiph.2010.20609

30. Bayih WA, Birhan BM, Yeshambel Abebaw AM, Asfaw M. Determinants of maternal knowledge of neonatal danger signs among postnatal mothers visiting neonatal intensive care unit, north Central Ethiopia, 2019: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):218. doi:10.1186/s12884-020-02896-x

31. Asnakew DT, Engidaw MT, Gebremariam A. Level of knowledge about neonatal danger signs and associated factors among mothers who delivered at home in Fogera District, South West, Ethiopia. Biomed Stat Inf. 2018;3(4):53–60. doi:10.11648/j.bsi.20180304.11

32. Sandberg J, Pettersson KO, Asp G, Kabakyenga J, Agardh A, Rubens C. Inadequate knowledge of neonatal danger signs among recently delivered women in southwestern rural Uganda: a community survey. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):5. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0097253

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.