Back to Journals » International Medical Case Reports Journal » Volume 11

Intestinal tuberculosis in a 55-year-old woman with a 30-year history of rheumatoid arthritis

Authors Mansour-Ghanaei F, Joukar F , Samadi A , Mavaddati S , Daryakar A, Gharibpour F

Received 17 January 2018

Accepted for publication 9 May 2018

Published 10 July 2018 Volume 2018:11 Pages 151—155

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IMCRJ.S162908

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Ronald Prineas

Fariborz Mansour-Ghanaei,1 Farahnaz Joukar,2 Alireza Samadi,1 Sara Mavaddati,1 Arash Daryakar,1 Fatemeh Gharibpour3

1Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases Research Center, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran; 2Caspian Digestive Diseases Research Center, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran; 3Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

Introduction: Tuberculosis (TB) is one of the endemic diseases with a challenging diagnosis in the absence of pulmonary disease. On the other hand, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a systemic autoimmune disease with extra-articular manifestations that occur at any age after onset, such as nodules, Sjögren’s syndrome, anemia of chronic disease, and pulmonary manifestations, which are more frequently seen in patients with severe, active disease. Here we present a case of RA with intestinal TB.

Case report: A 55-year-old woman with a 30-year history of RA using prednisolone and hydroxychloroquine presented with a nonpositional hypogastric pain and a weight loss of 20 kg over 7 months. No history of biological therapy was recorded. Colonoscopy revealed an ulcerated mass that was suspicious for malignancy. The pathobiological assessments confirmed ulceration and granulation tissue formation, foci of necrotizing granulomatous inflammation in lamina propria with adjacent mild crypt regenerative changes. Also, Ziehl–Neelsen staining for acid-fast bacilli in the granulomas was positive though the polymerase chain reaction assay did not detect the Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Anti-TB medication for 2 weeks eliminated the symptoms.

Conclusions: Intestinal TB in patients with vague abdominal symptoms and relevant physical findings such as pain and palpable mass should be considered to prevent late or misdiagnosis.

Keywords: intestinal tuberculosis, rheumatoid arthritis, colonoscopy, pathology, diagnosis

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a major health problem in developing countries.1 Regarding the advent of effective therapy,2 the probability of the rare extrapulmonary tuberculosis is not negligible.3 Intestinal TB (ITB) is the sixth most common extrapulmonary presentation4 with notorious innate which should be considered before a definite diagnosis, especially in areas where TB is prevalent.5

According to the existing reports in the literature, several conditions such as after anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy including concomitant use of immunosuppressants, history of latent or active TB, and being born in or spending extensive time in endemic areas would make patients susceptible for TB development.1

Case report

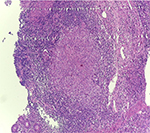

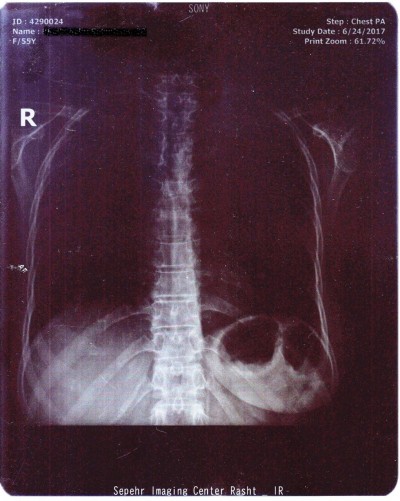

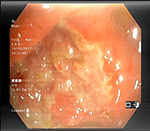

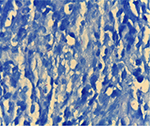

A 55-year-old woman was admitted to the Internal Medicine Department of Razi Hospital in Rasht (a city in the north of Iran) with a 30-year history of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). She declared a hypogastric, nonpositional pain without any relation to defecation or feeding, for 2 months, with previous constipation (had been cured with lactulose). Each pain episode lasted for ~5–10 minutes. She had a weight loss of 20 kg over the last 7 months. Also, had undergone endoscopy the previous year for the symptoms of nausea, diarrhea, and epigastric pain with eradicated Helicobacter pylori gastritis after a 4-week treatment. Although she had chronic anemia, there was no history of drinking alcohol or smoking, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, hyperlipidemia, or hypertension. In addition, she took prednisolone 5 mg, hydroxychloroquine 20 mg, hematinic, and supplements such as calcium, folic acid, and multivitamins daily. Furthermore, a self-discontinuation of methotrexate (MTX) was noted. The colonoscopy was performed, and only an ulcerated mass in the hepatic flexure was seen, and a biopsy was taken. As the endoscope could not pass through the hepatic flexure, the procedure was stopped (Figure 1). The pathobiological features revealed ulceration and granulation tissue formation, foci of necrotizing granulomatous inflammation in lamina propria with adjacent mild crypt regenerative changes (Figure 2). Moreover, Ziehl–Neelsen stained sections (Figure 3) revealed few acid-fast positive bacilli in the granuloma. No evidence of dysplasia or malignancy was found in the received sample. Meanwhile the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for ITB was negative. In order to rule out pulmonary TB, radiography was performed with no evidence of pulmonary involvement (Figure 4). Follow-up after a 2 week treatment with anti-TB medication demonstrated the complete disappearance of the symptoms. A written informed consent form has been provided by the patient to have the case details and any accompanying images published.

| Figure 1 An ulcerated mass in the hepatic flexure. |

| Figure 3 Acid-fast positive bacilli in the granuloma (Ziehl-Neelsen’s stain, 100×). |

| Figure 4 The chest X-ray showed no evidence of pulmonary involvement. |

Discussion

TB is one of the infectious diseases prevalent all around the world.6 The gastrointestinal TB leads to significant morbidity and mortality as most of the time it is not timely diagnosed and mimics other disorders such as colon cancer, lymphoma, appendicitis (as the main presumptive diagnosis),6 Crohn’s disease (CD), actinomycosis, or other infectious diseases.5 The coexistence of pulmonary TB (active or healed) and gastrointestinal TB is not common. It is reported that approximately <25% of patients have both.7 Also, colonic tuberculosis cases without systemic features have been published.8 According to its nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms, the diagnosis is more difficult in the absence of pulmonary TB.9

The total involvement of gastrointestinal tract from the esophagus to rectum through the swallowed bacterium by a hematogenous spreading or from adjacent organs is probable.7,10,11 The frequency of involvement is different. It is stated that just 1%–3% of TB cases have ITB. In addition, it’s occurrence in distal parts of the ileocecal junction is very rare.12 However, terminal ileum has more inclination for the infection after a long term intestinal mucosa contact.7,10,11

Abdominal pain is the frequent symptom in almost all cases (>85%). Also, abdominal distension, poor absorption, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, and weight loss are the other symptoms.13,14 Furthermore, palpable abdominal mass in physical examination is the other common finding. Nevertheless, the digestive bleeding is very rare.15 Our patient’s symptoms were more relevant to a neoplastic mass.

Although diffuse tuberculosis colitis is not common, inflammatory stricture, polyps or tumors, and segmental ulcers are the most probable presentations.16 The most important endoscopic findings are ulceration, nodularity, and luminal narrowing, which mostly impact the right colon. Also, ulcers are usually seen in the colonoscopy of patients with colonic TB (70%).17 Alvares et al have reported granulomas in >54% of the colonic biopsies,17 which are the most common histopathological feature of colonic TB. In endemic areas for TB, distinguishing between ITB and CD is very demanding due to the presence of granuloma.5 However, the morphology of tuberculous ulcers is not the same as Crohn’s ulcers. They are typically linear, transverse, fissured, or circumferential with abnormal surrounding mucosa.4 One of the considerable findings in our case was the negative result of PCR for TB while bacilli acid-fast staining was positive. According to the evidence of a recent systematic review study, PCR for Mycobacterium tuberculosis is suggested as a promising and highly specific diagnostic method to distinguish ITB from CD. However, negative results cannot exclude ITB because of its low sensitivity. Additional prospective studies are needed to further evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of PCR.12 In nonendemic countries, the colonic diagnosis requires a high suspicion index of4of migrant population and immunosuppressed individuals. Though the deficient immune response among immunosuppressed patients can elevate the incidence and the severity of ITB,18 in rare cases, it would appear in a healthy immune system, such as in Brambilla et al’s report.2 Our case had a 30-year history of RA using hydrocortisone and prednisolone with self-discontinuation of MTX. There was no evidence of latent TB existence, based on no history of the tuberculin skin test; however, being infected with TB in our endemic region is not unexpected. As it is known that the majority of cases are treated properly with anti-TB treatment, and follow-up colonoscopy is not required in those who have symptomatic improvement,4 after completing the treatment, the colonoscopy was not performed.

Conclusion

The role of considering ITB in patients with vague abdominal symptoms and relevant physical findings, such as pain and a palpable mass, in early diagnosis and treatment is highly effective to prevent misdiagnosis of similar disorders such as CD or colonic malignancies. Also, it should be stated that the sensitivity of PCR rather than other diagnostic methods is low.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the members of Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases Research Center (GLDRC). We also thank the patient’s family for providing consent for this case report.

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Wang MH, Liu X, Shen B. Disseminated tuberculosis in a patient taking anti-TNF therapy for Crohn’s disease. ACG Case Rep J. 2015;3(1):45–48. | ||

Brambilla E, Dal Ponte M, Ruschel LG, Silva PGD. Intestinal tuberculosis in immunocompetent/HIV negative patients: case report of two patients. J Coloproctol (Rio de Janeiro). 2012;32(3):304–307. | ||

Santra G, Pani A, Biswas KD. Isolated rectal tuberculosis with multiple ulcers. J Assoc Physicians India. 2013;61(12):934–936. | ||

Mukewar S, Mukewar S, Ravi R,Prasad A, Dua KS. Colon tuberculosis: endoscopic features and prospective endoscopic follow-up after anti-tuberculosis treatment. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2012;3:e24. | ||

Wu YF, Ho CM, Yuan CT, Chen CN. Intestinal tuberculosis previously mistreated as Crohn’s disease and complicated with perforation: a case report and literature review. SpringerPlus. 2015;4:326. | ||

Khan M, Zahoor I, Haq E. Human immunodeficiency virus and multiple sclerosis risk: probing for a connection. J Mult Scler. 2015;2:2376–2389. | ||

Horvath KD, Whelan RL. Intestinal tuberculosis: return of an old disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(5):692–696. | ||

Choudhary A, Gupta NM. Colorectal tuberculosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1986;29:738. | ||

Shah S, Thomas V, Mathan M, et al. Colonoscopic study of 50 patients with colonic tuberculosis. Gut. 1992;33(3):347–351. | ||

Alvares JF, Devarbhavi H, Makhija P, Rao S, Kottoor R. Clinical, colonoscopic, and histological profile of colonic tuberculosis in a tertiary hospital. Endoscopy. 2005;37(4):351–356. | ||

Das HS, Rathi P, Sawant P, et al. Colonic tuberculosis: colonoscopic appearance and clinico-pathologic analysis. J Assoc Physicians India. 2000;48(7):708–7110. | ||

Jin T, Fei B, Zhang Y, He X. The diagnostic value of polymerase chain reaction for mycobacterium tuberculosis to distinguish intestinal tuberculosis from Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(1):3–10. | ||

Uzunkoy A, Harma M. Diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis: experience from 11 cases and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10(24):3647–3649. | ||

Lazarus AA, Thilagar B. Abdominal tuberculosis. Dis Mon. 2007;53(1):32–38. | ||

Kuntanapreeda K. Tuberculous appendicitis presenting with lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage-a case report and review of the literature. J Med Assoc Thai. 2008;91(6):937–942. | ||

Marshall JB. Tuberculosis of the gastrointestinal tract and peritoneum. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88(7):989–999. | ||

Alvares JF, Devarbhavi H, Makhija P, Rao S, Kottoor R. Clinical, colonoscopic, and histological profile of colonic tuberculosis in a tertiary hospital. Endoscopy. 2005;37(4):351–356. | ||

Donoghue HD, Holton J. Intestinal tuberculosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2009;22(5):490–496. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.