Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

Internal Corporate Social Responsibility and Employee Burnout: An Employee Management Perspective from the Healthcare Sector

Authors Liu Y, Cherian J, Ahmad N , Han H , de Vicente-Lama M , Ariza-Montes A

Received 15 September 2022

Accepted for publication 23 January 2023

Published 3 February 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 283—302

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S388207

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 5

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Yun Liu,1 Jacob Cherian,2 Naveed Ahmad,3,4 Heesup Han,5 Marta de Vicente-Lama,6 Antonio Ariza-Montes7

1Henan University of Economics and Law, Zhengzhou, People’s Republic of China; 2College of Business, Abu Dhabi University, Abu Dhabi, 59911, United Arab Emirates; 3Department of Management Sciences, Faculty of Management, Virtual University of Pakistan, Lahore, 54000, Pakistan; 4Faculty of Management Sciences, University of Central Punjab, Lahore, 54000, Pakistan; 5College of Hospitality and Tourism Management, Sejong University, Seoul, 143-747, Korea; 6Department of Financial Economics and Accounting, Universidad Loyola Andalucía, Córdoba, 14004, Spain; 7Social Matters Research Group, Universidad Loyola Andalucía, Córdoba, 14004, Spain

Correspondence: Heesup Han, Email [email protected]

Purpose: The issue of burnout has been identified as one of the most pressing challenges in organizational management, impacting the ability of an organization to succeed as well as employee productivity. In the healthcare industry, burnout is particularly prevalent. Burnout has received increasing attention from scholars, and different models have also been proposed to address this issue. However, burnout is on the rise in healthcare, especially in developing countries, indicating the need for more research on how to mitigate burnout. Research indicates that internal corporate social responsibility (ICSR) has a significant impact on employee behavior. However, little attention has been paid to exploring how ICSR might effectively reduce healthcare burnout. This study aims to investigate how ICSR and employee burnout are related in the healthcare sector of a developing country. In addition, we tested how subjective well-being and resilience mediate and moderate the effect of ICSR on employee burnout.

Methods: Data were collected from 402 healthcare employees working in different hospitals in Pakistan. In our study, we used a self-administered questionnaire as a data collection instrument. We have adapted the items in this survey from reliable and already published sources. Data collection was carried out in three waves.

Results: Hypotheses were evaluated using structural equation modeling (SEM). Software such as IBM-SPSS and AMOS were used for this purpose. ICSR significantly reduces healthcare employees’ burnout, according to the results of the structural analysis. The relationship between ICSR and burnout was also found to be mediated by subjective well-being, and resilience moderated the relationship between ICSR and subjective well-being.

Findings: In light of our findings, hospitals can take some important steps to resolve the problem of burnout. The study specifically stresses the importance of ICSR as a contextual organizational resource for preventing burnout among healthcare employees.

Keywords: internal corporate social responsibility, burnout, healthcare, resilience, subjective well-being

Introduction

Contemporary organizations face a dynamic business environment characterized by technological progress and competitiveness,1,2 which increases work demand on the part of employees. Employees in various sectors of an economy are often asked to assume more work-related responsibilities, which ultimately negatively influences their mental and physical health. All such situations put employees in conditions where they face burnout risk.3 Burnout is described as a syndrome that includes emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, helplessness, and an imbalance of work-life.4 Although burnout may exist in any profession, healthcare employees are at greater risk of burnout.5 To make matter worse, burnout among healthcare employees has been reported to be rising globally.6 Unquestionably, burnout is a serious public health concern that causes different physical health disorders, including aches and digestive upset. Along with different physical disorders, burnout is equally dangerous for mental health because it has been related to different psychiatric disorders, for example, depression,7 anxiety,8 substance abuse,9 and even suicide among healthcare employees.10 The issue of burnout is critical in the healthcare sector, influencing employees’ mental and physical health and undermining the quality of healthcare delivery, including patient care.

In an enterprise milieu, certain enterprise factors influence employees’ mental health, including enterprise environment and managerial support.11–13 In this respect, the concept of corporate social responsibility (CSR) was recently related to different employee-related outcomes.14–16 Originally focused on institutional analysis, CSR has shifted almost exclusively to organizational analysis in the last few decades.17 Literature on CSR has been reviewed on three levels of analysis by Aguinis and Glavas:18 organizational, institutional, and individual. Generally, macro-level issues have been studied without focusing on micro-foundations-which are the foundations based on individual action and interaction in the field.19 The institutional theory advocated understanding micro-foundations almost three decades ago,20,21 but micro-level processes have not been explored as a method for understanding macro-level events and relationships until recently.22 As a result of the knowledge gap regarding underlying processes and lack of analysis at the individual level, Aguinis and Glavas18 have identified micro-foundations of CSR (ie, foundations of CSR that are based on individual action and interaction, based on strategic management literature.19 Accordingly, micro-CSR focuses on the ways in which CSR impacts individual stakeholders (in any stakeholder group).23 A number of CSR scholars have embraced the concept of micro-foundations after the concept appeared in academic literature.24–26 Even the role of CSR was highlighted to reduce different work-related outcomes, for example, emotional exhaustion,27 turnover intentions,28 and other workplace stressors.29 However, the literature on the ICSR-burnout relationship, especially in the healthcare management of low and middle-income economies, is sparse. To close this gap, we aim to investigate how ICSR relates to burnout in healthcare.

Different individual factors also contribute to limiting burnout risk. In this respect, the mediating role of subjective well-being perceptions of employees was realized previously. Indeed, subjective well-being is defined as “the cognitive and affective evaluation of an individual about his or her life”.30 Subjective well-being not only improves employees’ mental health but also helps them to recover from stressful conditions.31 Even in the burnout literature, the influence of subjective well-being has been discussed.32 Recently, Lan, Liang33 identified the mediating effect of subjective well-being in a burnout framework. Past literature verifies a positive association between ICSR and subjective well-being.34,35 Nonetheless, in a healthcare context, the mediating effect of subjective well-being between ICSR and burnout was not investigated earlier. Hence, it is worthwhile to investigate this relationship in a healthcare context where the challenge of burnout is more critical compared to other sectors. Thus, this study aims to investigate the mediating candidature of subjective well-being betwixt ICSR and burnout.

Another important psychological factor that helps a person in mitigating burnout risk is resilience which is referred to as “a psychological factor that an individual possesses to get rid of extreme situations they face”.36 Indeed, employees with a higher level of resilience have greater positive energy, which improves their ability to bounce back against burnout.37 Specifically, it was argued that when an individual faces extreme situations led by stress or any trauma, the resilience level of a person enables him to keep functioning both mentally and physically. In this respect, the moderating role of resilience in reducing the burnout effect was highlighted previously.38,39 Literature also suggests that CSR positively influences individual resilience.40 Still, the moderating role of resilience to mitigate healthcare employees’ burnout in an ICSR framework remained an understudied area previously. Hence it is relevant here to mention that ICSR, as an organizational-level factor, focuses on the well-being of employees and hence influences employees’ psychology positively, thereby improving their resilience. Employees with improved resilience as an outcome of ICSR may show greater energy to fight against burnout risk. Hence, this study’s last objective is to test the conditional indirect influence of resilience in a healthcare system.

We aim to test the hypothesized relationships of this study in the healthcare segment of a developing country, Pakistan. Like in other parts of the world, burnout is a critical challenge in the healthcare profession of Pakistan.41,42 Indeed, compared to developed countries, most developing countries face a difficult situation in healthcare management because of limited financial resources and other constraints.43,44 Specifically, Pakistan’s healthcare sector faces different challenges, leading to employee burnout issues. For example, limited staff, high patient-to-healthcare staff ratios, an increasing population, infrastructure, etc., often lead employees to face pressure situations,45 increasing the likelihood of employee burnout in this profession. As different organizational interventions may decrease employee burnout,46 we argue it will be interesting to see how the ICSR actions of a hospital organization can mitigate the likelihood of burnout.

Altogether, this research contributes to the existing literature significantly. First, this research advances the debate on burnout from an ICSR perspective. In this respect, the previous scholars investigated different factors that lead employees to face burnout conditions in an organization. For example, among several other factors, role conflict,47 role stress,48 and work overload49 were identified as enablers of burnout. Yet, how ICSR can reduce the burnout risk on the part of employees in a healthcare context received little attention. Second, this study is the first one that intends to test the mediating and moderating roles of subjective well-being and resilience in a unified model. Third, this study advances the debate on burnout in healthcare in a developing economy. In this respect, earlier researchers conducted burnout studies in the healthcare systems of developed or high-income countries.50,51 Because burnout at the workplace is a critical public health concern in most low and middle-income economies, it is important to advance this debate on how to reduce the burnout risk of employees in such countries.

Theory and Literature Review

Underpinning Theory

We used the conservation of resources theory (COR) to understand the underlying logic of the hypothesized relationships. Hobfoll52 developed this theory by arguing that “individuals tend to receive, construct and protect different valued resources in difficult situations”. Generally, there are two contrasting views that COR holds. The first view represents a value addition in resources, while the second view discusses the loss of valued resources. The value-added side of resources under the philosophy of COR suggests that individuals with sufficient resources are likely to have easy access to other resources, and thus such individuals are less likely to face a resource loss situation. Therefore, individuals with rich resources are expected to show better energy levels, commitment, and motivation to perform a job task in an organization.53

Contrary to this, individuals with a resource loss are expected to show weaker commitment and motivation to perform different organizational responsibilities.54 Building upon COR, this study argues that burnout, in an organizational context, represents a resource loss situation on the part of an employee. Employees with this perception that they have fewer resources or have lost some resources while performing a job are expected to develop stress, leading them to burnout. Employees need more resources to recover from the negative effects of burnout. This is the point where ICSR has a role to play. In this respect, we are in line with the previous scholars that CSR is an organizational resource that positively influences employees’ behavior and attitude.40 Especially the concept of ICSR relates well to the well-being of employees. An enterprise with better ICSR strategies for its employees is likely to provide its employees with better resources in the form of a balanced working environment, provide necessary training and development to face stressful conditions, and providing different other benefits under its CSR strategy for employees.55 At the same time, an ethical organization treats its employees fairly without showing any bias, which ultimately results in a higher level of meaningfulness.1,56 Buttressing this, Aguinis and Glavas57 showed that employees with meaningful work experience, as an outcome of ICSR, show an improved state of mental health, which provides them an additional resource to deal with different workplace situations. Therefore, CSR can reduce different negative workplace employee outcomes, for example, emotional exhaustion,27 which can help them to recover from a burnout state.

Hypotheses Development

Internal Corporate Social Responsibility and Burnout Relationship

ICSR refers to the actions and strategies of an organization to take the necessary steps for the satisfaction of employees.58 An organization with a focus on employees through its ICSR strategies proactively fulfills employees’ needs and intends to promote a culture of fairness, care, safety, and flexibility which ultimately improves the mental health of employees.59 Further, an ethical enterprise introduces different welfare programs under the umbrella of ICSR for employees’ wellness.60 The central idea of ICSR is to prioritize employees’ genuine concerns instead of taking care of only the organizational interests.61 Soni and Mehta62 indicated that certain ICSR actions of an organization, for example, supporting and helping the employees in achieving their job tasks, providing them with a good workplace environment, and arranging different pieces of training for their career growth and development, are some of the leading factors that enhance the commitment of employees. Besides noting the positive change in employees’ behavior as an outcome of ICSR, some recent researchers have also mentioned that ICSR is equally important for employees to recover from different negative externalities associated with a workplace.63 For example, the studies by Low, Ong,64 and Ranjan and Yadav65 established that different steps of an ethical organization under its ICSR philosophy help employees to develop a strong social bond with their organization which in turn mitigates their turnover intentions. Sanusi and Johl66 indicated that ICSR could enhance the job continuity intentions of employees with an ethical enterprise. Other scholars have mentioned the buffering effect of ICSR on emotional exhaustion67 and other negative emotions.68 Even in burnout literature, scholars have emphasized focusing on different intrinsic rewards (which is also a focus of ICSR) to effectively deal with burnout at the workplace.69 For example, providing different developmental training could help employees to build extra skills and mental strength to reduce burnout risk. Similarly, a flexible working atmosphere may also be helpful to the employees to recover from stressful situations.

ICSR actions of an organization can influence the emotions, attitudes, feelings and behaviors of employees. Equally important to mention is the role of ICSR in mitigating different negative emotional, attitudinal, and behavioral responses of an employee, including turnover intentions,70 emotional exhaustion,71 and burnout.72 Specifically, Rupp, Shao73 posited that CSR at an employee level caters to his or her deontic needs, which ultimately improves their emotional feeling towards their organization and hence creates positive energy among employees. Additionally, we are in line with extant CSR scholars who argue that CSR is an instrument strategy of an organization for workforce management that prevents employees’ negative attitudes and behaviors and ultimately improves overall performance.74,75 Flammer and Luo76 mentioned that ICSR is a tool for employee governance to reduce the likelihood of adverse employee behaviors. In a similar vein, Schwepker, Valentine77 CSR actions of an organization related to employees can reduce stress and improve their well-being.

To summarize, we expect that it may negatively predict burnout because ICSR focuses on the development, growth, and caring of the employees by providing them with different benefits and helping them achieve their job tasks. Employees in the healthcare profession often face stressful situations, which raises the chance of burnout for employees in such professions. Irregular working hours, high levels of strain, and other negative work-related situations in the healthcare profession deplete the physical and mental resources of employees. In this respect, ICSR-based actions of a hospital can play a seminal role in improving the positive energy level of employees, which consequently improves their mental and physical health. At the same time, ICSR improves employees’ wellness with a balanced work life. An ethical hospital provides employees with a safe working environment and protective context as part of its CSR plan, which helps employees absorb different work-related shocks Therefore;

H1: ICSR negatively predicts burnout among employees in an organization.

Internal Corporate Social Responsibility, Subjective Well-Being, and Burnout Relationships

ICSR aspect of CSR is well placed in subjective well-being literature. Generally, the discussion establishes a positive link between ICSR and the subjective well-being of employees.34,35 In an organizational milieu, subjective well-being deals with an employee’s cognitive and emotional evaluation of their workplace. In this respect, ICSR as an organizational factor improves the subjective well-being perceptions of employees because the central focus of different ICSR activities of an enterprise is to promote employees’ wellness.78 Bibi, Khan79 showed that ICSR activities of an enterprise lead the workers to a higher level of happiness. In this respect, it was established at different levels in the available literature that happier employees have better life satisfaction.80,81 Further, it was also mentioned that different enterprise-level interventions improve employees’ subjective well-being.82 ICSR covers a range of activities to improve employees’ safety and health.83 Further, ICSR activities directly influence the subjective well-being perceptions of employees.84 Additionally, the mediating role of subjective well-being in different organizational contexts was also mentioned in the extant literature. For instance, Singhal and Rastogi85 highlighted the mediating role of subjective well-being in explaining employees’ commitment. Similarly, in a recent study, Rūtelionė, Šeinauskienė86 mentioned that subjective well-being significantly mediates between emotional intelligence and materialism. Other scholars have also recognized subjective well-being as a significant mediator in predicting different employee outcomes.87 Further, as literature specifies that an improved level of subjective well-being reduces burnout significantly88 and as ICSR improves the subjective well-being perception of employees.

The existing discussion on the CSR-employee management relationship theoretically and empirically indicates that employees who find their employer socially responsible are expected to develop positive feelings and demonstrate a higher level of well-being, which ultimately triggers positive psychology in employees.34,89 Additionally, CSR scholars in the domain of ICSR have premeditated various boundary conditions to describe the underlying mechanism of how CSR-related actions of a firm influence rational, affective, and behavioral aspects of human psychology.90,91 Following this research stream, we argue that employees’ CSR perception toward their employer can influence their well-being level, which then helps employees in reducing the potential danger of burnout as a mediator. Specifically, positive employee psychology, for example, pride, loyalty, and belongingness have been long discussed from the standpoint of CSR.92,93 We contend that the current debate on employee negative attitudes and behaviors, in a CSR context, should also be considered to understand the underlying mechanism how ICSR can predict the attitude-behavior relationships on the part of employees. Specifically, we expect that ICSR based actions of a hospital organization improves the mental health of employees by enhancing the well-being perceptions. Employees with an enhanced level of well-being are likely to show more resistance against the risk of burnout because of the additional personal resource in the form of well-being. Therefore;

H2: ICSR is positively related to subjective well-being among employees. H3: Subjective well-being significantly mediates the relationship between ICSR and burnout among employees.

Internal Corporate Social Responsibility, Resilience, and Burnout Relationships

Zautra, Hall36 described resilience as a personal capability of a person which he or she possesses to recover from extreme situations. Various scholars have indicated the potential role of resilience in driving employees’ well-being and mental health.94,95 Previously, researchers studied resilience from the aspect of general life or non-workplace contexts.96 However, the pressure situations that employees face in different segments of the economy increased the interest of organizational management theorists in studying resilience in a workplace context.97,98 Further, the concept of resilience was identified as the personal capability to cope or adapt to different workplace stressors. Nonetheless, Richardson99 indicated that resilience is a personal dynamic capability influenced by different enterprise factors, such as leadership.100 Recently, the concept of resilience has been related to ICSR by different scholars in the field.40,101 It was realized that resilient employees show a better capability to deal with different workplace stressors.102 The capacity for hope, optimism, and self-efficacy of a resilient person helps them cope with challenges.23 In response to a crisis, resilience is often described as “bouncing back” to normal. Psychological resilience has been associated with a range of positive psychological outcomes, such as psychological adjustment103 and psychological health.104 It is well known that psychological resilience contributes to well-being as well as emotional expression. In recent research, resilience has been shown to be a strong predictor of subjective well-being.105–107 Because healthcare employees often are exposed to stressful situations due to their job nature,108 a higher level of resilience may help them to deal with different work-related stressors effectively. Further, employee resilience positively influences subjective well-being.109,110

Different organizational management scholars have discussed the moderating role of resilience in improving employees’ subjective well-being.110 For example, Chen111 proposed the moderating role of resilience to predict subjective well-being via coping style as a mediator. Darvishmotevali and Ali110 empirically verified that self-efficacy, optimism, and resilience are significant moderators in predicting job performance and subjective well-being. Jiang, Ming112 highlighted the moderating role of resilience to enhance the subjective well-being of employees. All in one, because the moderating role of resilience was emphasized by various researchers previously and as CSR influences resilience positively, we expect that resilience will improve the subjective well-being of hospital employees, which then reduces burnout. Moreover, following COR, resilience, as an outcome of ICSR, provides employees with an added personal resource that helps them in situations of resource bleeding due to burnout situations. Therefore, the following hypotheses may be framed.

H4: ICSR is positively related to resilience among employees. H5: Resilience significantly moderates the mediated relationship of ICSR and burnout through subjective well-being.

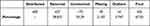

Figure 1 is the proposed model where all study variables and research hypotheses are included. Moreover, a summary of the related literature has also been provided in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Previous Contributions from CSR Scholars with Respect to Negative Employee Outcomes, Including Burnout |

|

Figure 1 Theoretical framework. |

Methodology

Study Sector

Pakistan’s healthcare industry was the target segment of this research, which is a lower-middle-income country in South Asia. Identified as a populous country in the world, the country has 275.3 inhabitants per square kilometer. As with most other lower and middle-income countries across the globe, the healthcare system of Pakistan faces an overburdened situation due to limited resources and infrastructure availability. Especially the hospitals in Lahore and Karachi cities have to deal with a vast number of indoor and outdoor patients on a daily basis. Both cities are provincial capitals with a multi-million population. Additionally, the public health of the masses in the neighboring cities depends on the health facilities in these two cities. Besides the insufficient resources and infrastructure, the growing population also often leads hospitals to face a pressure situation.113 The healthcare facilities in the country are divided among public and private sector entities. In this respect, the private sector clearly outperforms the public sector by providing health facilities to almost 70% of patients.114 Among the list of 195 countries across the globe, Pakistan captures 154th place, indicating the country’s poor quality of healthcare facilities. Besides all the above factors, the poor doctor-to-patient ratio and the nurse-to-patient ratio is also a critical factor due to which healthcare employees face a stressful situation. Lahore and Karachi constitute many large public and private hospitals with a diverse umbrella of in and outpatients. Considering the availability of different hospitals in Lahore and Karachi and considering the huge numbers of patients that these two cities attend on a daily basis, we included Lahore and Karachi in our sampled cities.

Unit of Analysis, Sample, and Procedure

Hospital employees in Lahore and Karachi participated in this survey. Hence, the unit of analysis in this study was the individual employees working in hospitals. We contacted the administration of different hospitals to seek their prior permission. In response, six hospitals agreed to participate in this survey. We then adjusted different matters prior to interacting with hospital employees, for example, the possible dates and times to conduct the survey, etc. The hospital employees, working in different departments, were invited to participate in this survey. We used a convenient sampling technique to collect information from healthcare employees. Indeed, the hospital administration indicated different employees who were available during the time of this survey. We tried our best to visit a hospital during different shifts in the day. This was done to ensure (at least from our end) that maximum employees get the opportunity to share their views. Specifically, the data were gathered during October and November 2021.

Instrument

We used a self-administered questionnaire. The items were adapted from published sources (detail is given in the subsequent paragraph). To validate our adapted questionnaire, the statements given in this survey were assessed by the experts (academia and hospital sector).115–118 Also, we conducted pilot testing on a sample of 60 hospital employees. The result and this pilot testing showed significant reliability statistics. Moreover, we did not find any employee reporting difficulty in understanding the statements of our questionnaire. After these steps, the final questionnaire was given to hospital employees. The basic questionnaire outlay was divided into two major components, which included socio-demographics and variables-related information. We considered a five-point Likert scale to receive participants’ responses.

We comply with the major ethical bindings given in the Helsinki Declaration.119,120 Healthcare employees with different cadres (employees with managerial responsibilities and non-managers) were included in this survey. Physicians and other related staff (paramedical) filled out this survey. To reduce fatigue and social desirability and to deal with common method bias (CMB), we used a three-wave strategy for data collection. A two-week interval separated each wave.

Sample Size

To estimate the expected recommended sample size, we use the famous online A-priori calculator of Daniel,121 which has been specifically designed for a specific structural analysis. Indeed, this calculator considers a number of factors to estimate recommended sample size for a specific structural analysis. For example, it is based on the number of latent factors (5 in this study), observed variables (23 in this study), probability level (we set at 0.05), and effect size (we set at normal). Based on these inputs, the calculator showed we need to have a sample size of 376. Knowing the fact that the survey researchers do not give a 100% response rate, we intentionally distributed 600 questionnaires to get as close as possible to this recommended number. Various other social scientists have also used this technique to estimate the sample size.122,123

Data Cleaning

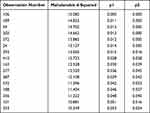

Primarily, we initially distributed 600 questionnaires to healthcare employees. We did not receive back 173 questionnaires (which is common in survey research). Specifically, 83 responses were not returned during the first wave (T1), and 48 responses were dropped during the second wave (T2). Lastly, we did not receive 42 responses in the third wave (T3). Thus we received 427 filled responses, which were then tested for data cleaning (missing values and outliers). The data-cleaning process further dropped the usable responses to 402 (Table 2). We used the Mahalanobis measure to detect the outliers in AMOS software. These results are represented in Table 2. In this respect, 16 cases were identified as outliers.

|

Table 2 Data Cleaning, Outliers, and Response Rate |

Male respondents were 43%, while females were 57%. The majority of the employees belong to 18 to 45 years (89%). Employees’ experience varied from 1 year to 7 years in most cases. See Tables 2 and 3 for more detail on data cleaning.

|

Table 3 Outliers |

Measures

As specified earlier, the items were adapted from already reliable published sources. Six ICSR items were adapted from Turker,124 who introduced a seventeen-item scale to measure CSR from employees, customers, government, and general perspectives. However, we only used six-employee related items. One sample item was “Our hospital implements flexible policies to provide a good work and life balance for employees.” The items to measure resilience -RS were taken from Smith, Dalen,125 who developed a brief resilience scale (also known as BRS-6) that included six items. An item from this scale included “I tend to bounce back quickly after hard times.” The variable subjective well-being- SB was measured by using four items from Lyubomirsky and Lepper.126 One sample from this scale was “In general, I consider myself a very happy person” To measure burnout- BUO, we adapted the items from the study of Kristensen, Borritz,127 who introduced the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI) to measure BUO. Seven items were included from CBI to measure the workplace BUO. A sample item was “I feel my work is emotionally exhausting” To verify the reliability (inter-item consistency), we checked the Cronbach alpha (α) value in every case. The results indicated significant values (>0.7).128 (α = 0.87 for ICSR; 0.87 for RS; 0.79 for SB; and 0.89 for BUO).

Common Latent Factor Test to Detect Common Method Bias

We executed the common-latent-factor (CLF) technique to detect CMB by developing two measurement models. Among the two models, one was the actual model (four-factor without any CLF), and the second measurement model was contrasted with a CLF. Both models were compared to detect a significant difference in any factor loading (>0.2). This comparison revealed no significant difference, establishing that a CMB was not a point of concern in this survey.

Results

Reliability and Validity

We verified the variables’ validity and reliability (ICSR, RS, SB, and BUO) in this study. First of all, we performed convergent validity tests. Before calculating the convergent validity, we tested each item’s factor loading. It was realized that all items’ loadings were significant (above 0.7), indicating that most variances in a variable were explained by the items, not by the associated error term. This CFA output provided statistical-based evidence about the goodness of our theoretical model to the database model. Table 4 presents the detail on factor loadings. Based on these factor loadings, we calculated all variables’ average-variance-extracted (AVE) values. The AVE in every case was above 0.5, which was significant, verifying the convergent validity of each variable.129,130 It can be seen from Table 3 that AVE values ranged from 0.54 to 0.60 (for ICSR and BUO). These results provided statistical support that each variable had a significant level of convergent validity.

|

Table 4 Validity and Reliability |

Next, we tested the reliability, especially the composite reliability. The output of the composite reliability analysis indicated that each variable achieved a good level of composite reliability (greater than 0.7). Specifically, the values ranged from 0.83 to 0.91 (for SB and BUO) (see Table 4).

Model Fitness

Model fitness was assessed by observing different model fit indices values. We, in this respect, developed four measurement models, among which one was the actual hypothesized model, whereas three models were alternate models. The composition of these alternate models and the actual hypothesized model can be observed in Table 4. First, a one-factor (alternate) model was developed, showing poor model fitness. Later on, two and three-factor models were developed. When compared, it was realized that no alternate model could produce superior model fit indices than the hypothesized model. We assessed different model fit indices, including the goodness of fit index➔GFI, Tucker Lewis index➔TLI, incremental fit index➔IFI, comparative fit index➔CFI, root mean square error of approximation➔RMSEA, and chi-square➔χ2 values were observed against their standard acceptable ranges. In this respect, the actual hypothesized model showed GFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.94, IFI = 0.96, CFI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.05, and χ2/df = 2.13. All these values indicated that the actual hypothesized model fits well with the dataset of this survey (see Table 5).

|

Table 5 Model Fit Comparison, Alternate vs Hypothesized Models |

Correlations

We also performed a correlation analysis (Table 5). The results indicated that some pairs of variables showed negative relationships (for example, ICSR<≤ BUO = −0.57), whereas some pairs indicated a positive nature of the association (for example, ICSR<≤ SB = 0.55). Further, we did not detect any case with extreme values (> 0.8). This indicates multicollinearity was not critical in this survey. Lastly, we examined discriminant validity for each variable, and it was realized that discriminant validity was significant in each case (see Table 6).

|

Table 6 Correlations and Discriminant Validity |

Hypotheses Testing

Structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis helped us to analyze hypothesized relationships. Indeed, SEM is an advanced level data analysis technique which is very famous among contemporary researchers.131–135 AMOS version 23 was used to carry out SEM analysis. In this respect, the PROCESS macro version 4.1 was also used to build a user-defined estimand in AMOS to calculate the conditional indirect effect at a different level of the moderator (below one standard deviation, above, and at mean). We acknowledge the efforts of Hayes, who introduced this macro which is helpful in calculating different complex models.136,137 The predictor and moderator variables were mean-centered before performing SEM to test the conditional effect of RS. Similarly, an interaction term was also generated by taking the product of ICSR and RS. A bootstrapping sample size of 5000 was used for estimating mediating and moderating effects. The results showed a negative relationship between ICSR and BUO. Specifically, the direct effect regression equation showed that when BUO was regressed on ICSR, it showed negative results. These results were significant because lower and upper confidence intervals (CI) did not include zero. Similarly, when SB and RS were regressed on ICSR, they produced positive results, indicating that ICSR positively and significantly explained SB and RS. These results supported the theoretical statements of H1, H2, and H4.

The mediation analysis showed that SB significantly mediates between ICSR and BUO because the bootstrapping confidence intervals (lower and upper) were significant, supporting H3. Lastly, the conditional indirect effect of RS was also significant between the mediated relationship of ICSR and BUO through SB because when introduced in the model, RS produced a buffering effect in the above-mediated relationship (beta value = −0.085). Hence, H1, H2, H3, H4, and H5 were accepted (see Table 7). Figures 2 and 3 include the measurement model and structural model.

|

Table 7 Direct, Indirect, and Conditional Effects |

|

Figure 2 Measurement model. |

|

Figure 3 Structural model. |

Discussion of Key Findings

As anticipated, the statistical evidence supported our theoretical assumption that the ICSR orientation of an ethical hospital mitigates employees’ burnout risk (beta = −0.59). The key findings of this research suggest that the ICSR philosophy of a hospital organization tends to boost the morale of employees and encourage them to show more strength against burnout. This key finding is in line with previous researchers.69,138 Similarly, our study suggests that the ICSR context of a hospital provides employees with different kinds of extra resources which work as a shield to protect them against the bleeding of resources in burnout situations. An organization pursues a flexible environment, supporting and helping the employees, and developing their skill sets are some of the distinguishing features of its ICSR strategy. The prior studies also confirm that ICSR relates to an improved level of mental health of employees.60,66 Thus employees of an ethical organization feel less threat of resource bleeding in stressful conditions as they feel the organizational support is always there to recover from extreme situations.

Another important key finding of our study is to highlight the mediating role of employees’ subjective well-being perception in explaining burnout (beta = −0.27). In this vein, our results show that ICSR not only reduces the risk of burnout among employees, but it also improves their subjective well-being perceptions. When employees have strong well-being perceptions, as an outcome of ICSR, it serves as an added resource that strengthens employees’ capability to combat burnout conditions, which healthcare employees often face. Although the direct negative relationship between ICSR and burnout was significant in our study, the results further confirmed that subjective well-being significantly mediated ICSR-burnout relationship. Other researchers have also emphasized the mediating role of subjective well-being to explain different employee outcomes.86,139 Even in a healthcare context, our confirmation that subjective well-being is a mediator to explain healthcare employees’ behavior receives support from extant healthcare researchers.33,140 Specifically, our findings contend that ICSR improves the subjective well-being perceptions of employees because the central focus of different ICSR activities of an enterprise is to foster employees’ wellness, which then helps them to deal with burnout situations effectively. Hence our study confirms that ICSR positively influences the subjective well-being perception of employees, which consequently mediates the ICSR-burnout relationship.

Lastly, our empirical findings confirmed the moderating function of resilience between the mediated relationship of ICSR and burnout via subjective well-being. In this respect, it was realized that resilience as a moderator creates a buffering effect between the negative relationship of ICSR and burnout such that in the presence of resilience, the risk of burnout is reduced to a further level (beta =−0.085). Specifically, ICSR not only positively predicts employees’ subjective well-being but also significantly influences employee resilience, which then provides buffering support as a moderator to reduce burnout. Other ICSR researchers have also indicated ICSR relates to employee resilience.40,101 It was realized that resilient employees, as an outcome of ICSR, show a better capability to deal with different workplace stressors. Specifically, early research studies in employee behavior also acknowledged the moderating role of resilience in coping with negative work-related outcomes, including stress and burnout.104,141 However, our study identifies the moderating role of resilience in an ICSR framework to mitigate healthcare employees’ burnout. We expect employees with higher resilience to promote themselves on a higher level of subjective well-being, which then reduces the risk of burnout. Thus, our results confirm the conditional indirect role of resilience between ICSR and burnout via subjective well-being.

Theoretical Implications

Our research advances theoretical debate by offering the following important insights. First, this study advances the debate on burnout from an ICSR perspective. In this respect, the previous scholars investigated different factors that lead employees to face burnout conditions in an organization. For example, among several other factors, role conflict,47 role stress,48 and work overload49 were identified as enablers of burnout. Yet, how ICSR can reduce the burnout risk on the part of employees in a healthcare context received little attention. Accordingly, ICSR’s policies and practices of an ethical hospital are aimed at helping its employees maintain psychological and physiological well-being. The action focuses on expanding employee volunteer opportunities and building company-specific human resources. Organizations under the umbrella of ICSR are responsible for their employees’ careers and needs, including their education. It is important to note that ICSR has a positive impact on employees’ psychology as an organizational resource. A hospital that practices ICSR improves the subjective well-being of employees, which reduces burnout. An ethical organization provides its employees with the resources they need in order to express themselves effectively, both physically and cognitively. Therefore, ICSR is an important microstructure imperative for organizational management. ICSR allows employees to maintain work-family balance, reduce pressure caused by various situational and work-related factors, and maintain flexibility in the workplace. ICSR-based ethical hospitals provide resources for work to improve employee welfare. The hedonic and eudemonic well-being of employees are positively impacted by ICSR. By providing adequate resources, psychological symptoms associated with stress and high work demands are likely to be reduced, thereby helping to reduce burnout. This argument is in agreement with the study by Ramdhan, Kisahwan,138 which claimed that ICSR significantly improves job performance and reduces employee burnout. Second, this study is the pioneer one that attempts to test the mediating and moderating effects of subjective well-being and resilience in a unified model to understand how these two factors contribute to reducing burnout risk in a CSR framework. Considering the complexity of human psychology, it was important to understand the underlying mechanism of how ICSR-based actions of an ethical hospital reduce employee burnout through well-being and resilience. To this end, Subjective well-being not only improves employees’ mental health but also helps them to recover from stressful conditions. Similarly, as a personal resource, resilient employees are expected to have a greater level of positive energy, which improves their ability to bounce back against burnout. Healthcare employees, when face extreme situations led by stress or any trauma, their resilience level enable them to keep functioning both mentally and physically. Hence, the manifestation of well-being and resilience may reduce employee burnout significantly in an ICSR framework.

Yet another theoretical insight of our study is that it extends the burnout debate in a healthcare context of a low-middle-income country. In this respect, most of the prior researchers conducted burnout studies in the healthcare context of developed or high-income countries.50,51 Considering the increasing criticality of work-related burnout in most low and middle-income countries, it was important to advance this debate on how to reduce the burnout risk of employees in such countries.

Practical Implications

The practical aspect of our research study is also notable as our study helps the healthcare system by presenting ICSR as a remedy to combat the burnout situation. Healthcare employees often are exposed to stressful situations due to their job nature, which could lead to burnout situations. The burnout risk in healthcare reduces the quality of patient care and creates different mental disorders among employees. To this end, an ethical hospital organization can equip its workforce with the added resources in the form of different ICSR activities. A hospital organization with effective ICSR activities gives rise to the mental health and well-being of its employees. An improved level of mental health and well-being is very important for employees to reduce the threat of burnout. This finding is very important for the management of healthcare because the burnout phenomenon has been reported as a critical issue in different healthcare systems, especially in developing and underdeveloped countries. Specifically, we propose a critical implication to hospital administrators to carefully plan and execute ICSR policies for the staff from the perspective of burnout. The hospital administration needs to understand that ICSR policies not only improve the general well-being of the healthcare workers but also work as added resources to fight against burnout. Currently, most hospitals focus on different programs as part of ICSR, for example, allocating different funds for needy employees or giving them different flexibilities to perform their work. However, we suggest a careful reorientation of ICSR strategies from burnout’s perspective will help this sector.

Another important takeaway of our research on a practical landscape is to realize the importance of resilience and subjective well-being. Resilient employees are expected to have an improved level of subjective well-being, and thus they are expected to have less chance of facing a resource bleeding situation. From that aspect, too, well-planned ICSR activities are very important for a hospital because ICSR improves resilience at one end, it also improves the subjective well-being perceptions of employees.

From an economic aspect, our research tends to help the healthcare industry. As it was specified that different mental disorders, including burnout, create a dent of one trillion USD in the global economy, reducing the burnout threat among healthcare employees is critical for this segment. Especially in a developing country where health facilities already face a resource deficiency situation, mitigating the burnout threat as an outcome of ICSR can be really meaningful.

Limitations and Future Research

This study adheres to a few potential limitations. Firstly, the sample included only two large cities in Pakistan, which may undermine the generalizability of this study. Therefore, we recommend including more cities from other provinces. Due to different policies and security reasons, hospitals did not share any list of employees with us. Therefore, we had to use a non-probability convenient sampling strategy. In future studies, we recommend using a probability sampling strategy. We did not control for the age, gender, and experience of employees, which may be important. Therefore, in future studies, we recommend considering these control variables. Lastly, considering the complexity of human behavior formation, we suggest including more variables in the theoretical framework of this study. For example, individual values like altruism have a central role in behavior formation. Indeed, such values shape/influence various behavior of employees.1 Therefore, it will be interesting in future studies to include altruism as a moderator or mediator to predict burnout.

Conclusion

To conclude, we suggest Pakistan’s healthcare administration to deal with burnout by carefully planning different ICSR strategies. To effectively deal with the different work-related stressors, a hospital must develop better employee management strategies under the umbrella of ICSR. From a sustainability and mental health perspective, the concept of ICSR is well-placed in the literature on organization management. Along with different positive outcomes, ICSR is equally important for the employees of an organization to recover from different negative externalities and mental disorders, including burnout. We recommend hospital administration to carefully redefine the hiring and selection criteria of employees to identify resilient employees who can flourish better in an ethical hospital to recover from burnout situations. In this vein, we also recommend hospital administration arrange different pieces of training to improve the resilience level of employees. Such training sessions will be helpful for employees from resilience and well-being perspectives. All in one, if burnout is one of the pressing issues in healthcare, ICSR is a way forward to fix it.

Ethical Statement

The present research was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the research program committee of the Pakistan Kidney and Liver Institute (IRB Approval No. PKLI-IRB/AL/2021-07/042).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent has been obtained from all subjects involved in this study to publish this paper.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the financial support from the Projects of the National Social Science Foundation of China (No. 21BSH112; 19BGL131) and National pre-research project of Henan University of Economics and Law.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

1. Deng Y, Cherian J, Ahmad N, Scholz M, Samad S. Conceptualizing the role of target-specific environmental transformational leadership between corporate social responsibility and pro-environmental behaviors of hospital employees. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(6):3565. doi:10.3390/ijerph19063565

2. Zhang D, Mahmood A, Ariza-Montes A, et al. Exploring the impact of corporate social responsibility communication through social media on banking customer e-wom and loyalty in times of crisis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(9):4739. doi:10.3390/ijerph18094739

3. DeChant PF, Acs A, Rhee KB, et al. Effect of organization-directed workplace interventions on physician burnout: a systematic review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;3(4):384–408.

4. Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav. 1981;2(2):99–113. doi:10.1002/job.4030020205

5. De Hert S. Burnout in healthcare workers: prevalence, impact and preventative strategies. Local Reg Anesth. 2020;13:171. doi:10.2147/LRA.S240564

6. National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being. Washington, USA: National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine; 2019:0309495504.

7. Schonfeld IS, Bianchi R. Burnout and depression: two entities or one? J Clin Psychol. 2016;72(1):22–37. doi:10.1002/jclp.22229

8. Koutsimani P, Montgomery A, Georganta K. The relationship between burnout, depression, and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2019;10:284. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00284

9. Brown SD, Goske MJ, Johnson CM. Beyond substance abuse: stress, burnout, and depression as causes of physician impairment and disruptive behavior. J Am Coll Radiol. 2009;6(7):479–485. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2008.11.029

10. Ji YD, Robertson FC, Patel NA, Peacock ZS, Resnick CM. Assessment of risk factors for suicide among US health care professionals. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(8):713–721. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2020.1338

11. Sarfraz M, Qun W, Sarwar A, Abdullah MI, Imran MK, Shafique I. Mitigating effect of perceived organizational support on stress in the presence of workplace ostracism in the Pakistani nursing sector. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2019;12:839. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S210794

12. Fatima T, Bilal AR, Imran MK, Sarwar A. Manifestations of workplace ostracism: an insight into academics’ psychological well-being. South Asian J Bus Stud. 2021. doi:10.1108/SAJBS-03-2019-0053

13. Molnár E, Mahmood A, Ahmad N, Ikram A, Murtaza SA. The interplay between corporate social responsibility at employee level, ethical leadership, quality of work life and employee pro-environmental behavior: the case of healthcare organizations. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(9):4521. doi:10.3390/ijerph18094521

14. Ahmad N, Ullah Z, AlDhaen E, Han H, Scholz M. A CSR perspective to foster employee creativity in the banking sector: the role of work engagement and psychological safety. J Retail Consum Serv. 2022;67:102968. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.102968

15. Guo M, Ahmad N, Adnan M, Scholz M, Naveed RT, Naveed RT. The relationship of csr and employee creativity in the hotel sector: the mediating role of job autonomy. Sustainability. 2021;13(18):10032. doi:10.3390/su131810032

16. Murtaza SA, Mahmood A, Saleem S, Ahmad N, Sharif MS, Molnár E. Proposing stewardship theory as an alternate to explain the relationship between CSR and Employees’ pro-environmental behavior. Sustainability. 2021;13(15):8558. doi:10.3390/su13158558

17. Lee MDP. A review of the theories of corporate social responsibility: its evolutionary path and the road ahead. Int J Manage Rev. 2008;10(1):53–73. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2370.2007.00226.x

18. Aguinis H, Glavas A. What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: a review and research agenda. J Manage. 2012;38(4):932–968. doi:10.1177/0149206311436079

19. Foss N. Why micro-foundations for resource–based theory are needed and what they may look like. Invited Editorial J Manage. 2011;37(5):1413–1428.

20. DiMaggio PJ. The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis. Chicago, USA: University of Chicago Press; 1991.

21. Zucker LG. Postscript: microfoundations of institutional thought. N Institutional Organ Anal. 1991;103(106):1398–1438.

22. Powell WW, Colyvas JA. Microfoundations of Institutional Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2008.

23. Rupp DE, Mallory DB. Corporate social responsibility: psychological, person-centric, and progressing. Ann Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2015;2(1):211–236. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032414-111505

24. Ahmad N, Ullah Z, Arshad MZ, Waqas Kamran H, Scholz M, Han H. Relationship between corporate social responsibility at the micro-level and environmental performance: the mediating role of employee pro-environmental behavior and the moderating role of gender. Sustain Prod Consump. 2021;27:1138–1148. doi:10.1016/j.spc.2021.02.034

25. Kong L, Sial MS, Ahmad N, et al. CSR as a potential motivator to shape employees’ view towards nature for a sustainable workplace environment. Sustainability. 2021;13(3):1499. doi:10.3390/su13031499

26. Ahmad N, Ullah Z, AlDhaen E, Han H, Araya-Castillo L, Ariza-Montes A. Fostering hotel-employee creativity through micro-level corporate social responsibility: a social identity theory perspective. Front Psychol. 2022;13:154.

27. Xue S, Zhang L, Chen H. CSR, emotional exhaustion and turnover intention: perspective of conservation of resources theory. In: Academy of Management Proceedings. Briarcliff Manor, NY: Academy of Management; 2018:10510.

28. Kim JS, Song HJ, Lee C-K. Effects of corporate social responsibility and internal marketing on organizational commitment and turnover intentions. Int J Hosp Manage. 2016;55:25–32. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.02.007

29. Sroka W, Vveinhardt J. Is a CSR policy an equally effective vaccine against workplace mobbing and psychosocial stressors? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(19):7292. doi:10.3390/ijerph17197292

30. Diener E, Lucas RE, Oishi S. Subjective well-being: the science of happiness and life satisfaction. Handbook Positive Psychol. 2002;2:63–73.

31. Denovan A, Macaskill A. Stress and subjective well-being among first year UK undergraduate students. J Happiness Stud. 2017;18(2):505–525. doi:10.1007/s10902-016-9736-y

32. Qu H-Y, Wang C-M. Study on the relationships between nurses’ job burnout and subjective well-being. Chin Nurs Res. 2015;2(2–3):61–66. doi:10.1016/j.cnre.2015.09.003

33. Lan X, Liang Y, Wu G, Ye H. Relationships among job burnout, generativity concern, and subjective well-being: a moderated mediation model. Front Psychol. 2021;12. English. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.613767

34. Hu B, Liu J, Qu H. The employee-focused outcomes of CSR participation: the mediating role of psychological needs satisfaction. J Hosp Tour Manage. 2019;41:129–137. doi:10.1016/j.jhtm.2019.10.012

35. Golob U, Podnar K. Corporate marketing and the role of internal CSR in employees’ life satisfaction: exploring the relationship between work and non-work domains. J Bus Res. 2021;131:664–672. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.01.048

36. Zautra AJ, Hall JS, Murray KE. Resilience: a new definition of health for people and communities. 2010.

37. Seph FP. Resilience in positive psychology: how to bounce back. Maastricht, The Netherlands: Positive Psychology; 2017. Available from: https://positivepsychology.com/resilience-in-positive-psychology/#:~:text=Resilience%20in%20positive%20psychology%20refers,We%20call%20these%20people%20resilient.

38. García-Izquierdo M, Ríos-Risquez MI, Carrillo-García C, Sabuco-Tebar EÁ. The moderating role of resilience in the relationship between academic burnout and the perception of psychological health in nursing students. Educ Psychol. 2018;38(8):1068–1079. doi:10.1080/01443410.2017.1383073

39. Bernuzzi C, Setti I, Maffoni M, Sommovigo V. From moral distress to burnout through work-family conflict: the protective role of resilience and positive refocusing. Ethics Behav. 2021;2021:1–23.

40. Mao Y, He J, Morrison AM, Andres Coca-Stefaniak J. Effects of tourism CSR on employee psychological capital in the COVID-19 crisis: from the perspective of conservation of resources theory. Curr Issues Tour. 2021;24(19):2716–2734. doi:10.1080/13683500.2020.1770706

41. Yasir M, Jan A. Servant leadership in relation to organizational justice and workplace deviance in public hospitals. Leadersh Health Serv. 2022. doi:10.1108/LHS-05-2022-0050

42. Sun J, Sarfraz M, Ivascu L, Iqbal K, Mansoor A. How did work-related depression, anxiety, and stress hamper healthcare employee performance during COVID-19? The mediating role of job burnout and mental health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(16):10359. doi:10.3390/ijerph191610359

43. Adil MS, Baig M. Impact of job demands-resources model on burnout and employee’s well-being: evidence from the pharmaceutical organisations of Karachi. IIMB Manage Rev. 2018;30(2):119–133. doi:10.1016/j.iimb.2018.01.004

44. Ullah Z, Shah NA, Khan SS, Ahmad N, Scholz M. Mapping institutional interventions to mitigate suicides: a study of causes and prevention. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(20):10880. doi:10.3390/ijerph182010880

45. Chen J, Ghardallou W, Comite U, et al. Managing hospital employees’ burnout through transformational leadership: the role of resilience, role clarity, and intrinsic motivation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(17):10941. doi:10.3390/ijerph191710941

46. Wu Y, Li RYM, Akbar S, Fu Q, Samad S, Comite U. The effectiveness of humble leadership to mitigate employee burnout in the healthcare sector: a structural equation model approach. Sustainability. 2022;14(21):14189. doi:10.3390/su142114189

47. Xu L. Teacher–researcher role conflict and burnout among Chinese university teachers: a job demand-resources model perspective. Stud High Educ. 2019;44(6):903–919. doi:10.1080/03075079.2017.1399261

48. Kim H, Stoner M. Burnout and turnover intention among social workers: effects of role stress, job autonomy and social support. Adm Soc Work. 2008;32(3):5–25. doi:10.1080/03643100801922357

49. Weigl M, Stab N, Herms I, Angerer P, Hacker W, Glaser J. The associations of supervisor support and work overload with burnout and depression: a cross‐sectional study in two nursing settings. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(8):1774–1788. doi:10.1111/jan.12948

50. Montgomery A, Panagopoulou E, Esmail A, Richards T, Maslach C. Burnout in healthcare: the case for organisational change. BMJ. 2019;366. doi:10.1136/bmj.l4774

51. Cocchiara RA, Peruzzo M, Mannocci A, et al. The use of yoga to manage stress and burnout in healthcare workers: a systematic review. J Clin Med. 2019;8(3):284. doi:10.3390/jcm8030284

52. Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am Psychol. 1989;44(3):513. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

53. Ng TW, Feldman DC. Employee voice behavior: a meta‐analytic test of the conservation of resources framework. J Organ Behav. 2012;33(2):216–234. doi:10.1002/job.754

54. Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources theory: its implication for stress, health, and resilience. 2011.

55. Liu Z, Guo Y, Liao J, Li Y, Wang X. The effect of corporate social responsibility on employee advocacy behaviors: a perspective of conservation of resources. Chin Manage Stud. 2022;16(1):140–161. doi:10.1108/CMS-08-2020-0325

56. Xu L, Mohammad SJ, Nawaz N, Samad S, Ahmad N, Comite U. The role of CSR for de-carbonization of hospitality sector through employees: a leadership perspective. Sustainability. 2022;14(9):5365. doi:10.3390/su14095365

57. Aguinis H, Glavas A. On corporate social responsibility, sensemaking, and the search for meaningfulness through work. J Manage. 2019;45(3):1057–1086. doi:10.1177/0149206317691575

58. Jia Y, Yan J, Liu T, Huang J. How does internal and external CSR affect employees’ work engagement? Exploring multiple mediation mechanisms and boundary conditions. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(14):2476. doi:10.3390/ijerph16142476

59. Kim B-J, Nurunnabi M, Kim T-H, Jung S-Y. The influence of corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment: the sequential mediating effect of meaningfulness of work and perceived organizational support. Sustainability. 2018;10(7):2208. doi:10.3390/su10072208

60. Macassa G, McGrath C, Tomaselli G, Buttigieg SC. Corporate social responsibility and internal stakeholders’ health and well-being in Europe: a systematic descriptive review. Health Promot Int. 2021;36(3):866–883. doi:10.1093/heapro/daaa071

61. Farooq O, Rupp DE, Farooq M. The multiple pathways through which internal and external corporate social responsibility influence organizational identification and multifoci outcomes: the moderating role of cultural and social orientations. Acad Manage J. 2017;60(3):954–985. doi:10.5465/amj.2014.0849

62. Soni D, Mehta P. Manifestation of internal CSR on employee engagement: mediating role of organizational trust. Indian J Ind Relat. 2020;55(3):254.

63. Li X, Zhang H, Zhang J. The double-edged effects of dual-identity on the emotional exhaustion of migrant workers: an existential approach. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1266. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01266

64. Low MP, Ong SF, Tan PM. Would internal corporate social responsibility make a difference in professional service industry employees’ turnover intention? A two-stage approach using PLS-SEM. Glob Bus Manage Res. 2017;9(1):1463.

65. Ranjan S, Yadav RS. Uncovering the role of internal CSR on organizational attractiveness and turnover intention: the effect of procedural justice and extraversion. Asian Soc Sci. 2018;14(12):76–85. doi:10.5539/ass.v14n12p76

66. Sanusi FA, Johl SK. A proposed framework for assessing the influence of internal corporate social responsibility belief on employee intention to job continuity. Corporate Soc Responsibil Environ Manag. 2020;27(6):2437–2449. doi:10.1002/csr.2025

67. Jones DA, Newman A, Shao R, Cooke FL. Advances in employee-focused micro-level research on corporate social responsibility: situating new contributions within the current state of the literature. J Bus Ethics. 2019;157(2):293–302. doi:10.1007/s10551-018-3792-7

68. Onkila T. Pride or embarrassment? Employees’ emotions and corporate social responsibility. Corporate Soc Responsibil Environ Manag. 2015;22(4):222–236. doi:10.1002/csr.1340

69. Gabriel KP, Aguinis H. How to prevent and combat employee burnout and create healthier workplaces during crises and beyond. Bus Horiz. 2022;65(2):183–192. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2021.02.037

70. Chaudhary R. CSR and turnover intentions: examining the underlying psychological mechanisms. Soc Responsibil J. 2017;13(3):643–660. doi:10.1108/SRJ-10-2016-0184

71. Kumasey AS, Delle E, Agbemabiase GC. Benefits of promoting micro-level corporate social responsibility for emerging economies. In: Responsible Management in Emerging Markets. Springer; 2021:37–61.

72. Huang SY, Fei Y-M, Lee Y-S. Predicting job burnout and its antecedents: evidence from financial information technology firms. Sustainability. 2021;13(9):4680. doi:10.3390/su13094680

73. Rupp DE, Shao R, Thornton MA, Skarlicki DP. Applicants’ and employees’ reactions to corporate social responsibility: the moderating effects of first‐party justice perceptions and moral identity. Pers Psychol. 2013;66(4):895–933. doi:10.1111/peps.12030

74. Serrano Archimi C, Reynaud E, Yasin HM, Bhatti ZA. How perceived corporate social responsibility affects employee cynicism: the mediating role of organizational trust. J Bus Ethics. 2018;151(4):907–921. doi:10.1007/s10551-018-3882-6

75. Mehmood K, Jabeen F, Iftikhar Y, Acevedo-Duque Á. How employees’ perceptions of CSR attenuates workplace gossip: a mediated-moderation approach. In: Academy of Management Proceedings. Briarcliff Manor, NY: Academy of Management; 2021:10510.

76. Flammer C, Luo J. Corporate social responsibility as an employee governance tool: evidence from a quasi‐experiment. Strat Manage J. 2017;38(2):163–183. doi:10.1002/smj.2492

77. Schwepker CH, Valentine SR, Giacalone RA, Promislo M. Good barrels yield healthy apples: organizational ethics as a mechanism for mitigating work-related stress and promoting employee well-being. J Bus Ethics. 2021;174(1):143–159. doi:10.1007/s10551-020-04562-w

78. Chia A, Kern ML. Subjective wellbeing and the social responsibilities of business: an exploratory investigation of Australian perspectives. Appl Res Qual Life. 2021;16(5):1881–1908. doi:10.1007/s11482-020-09846-x

79. Bibi S, Khan A, Hayat H, Panniello U, Alam M, Farid T. Do hotel employees really care for corporate social responsibility (CSR): a happiness approach to employee innovativeness. Curr Issues Tour. 2022;25(4):541–558. doi:10.1080/13683500.2021.1889482

80. Diener E, Oishi S, Tay L. Advances in subjective well-being research. Nat Human Behav. 2018;2(4):253–260. doi:10.1038/s41562-018-0307-6

81. Naseem K. Job stress, happiness and life satisfaction: the moderating role of emotional intelligence empirical study in telecommunication sector Pakistan. J Soc Sci Human Stud. 2018;4(1):7–14.

82. Gray P, Senabe S, Naicker N, Kgalamono S, Yassi A, Spiegel JM. Workplace-based organizational interventions promoting mental health and happiness among healthcare workers: a realist review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(22):4396. doi:10.3390/ijerph16224396

83. Macassa G, da Cruz Francisco J, McGrath C. Corporate social responsibility and population health. Health Sci J. 2017;11(5):1–6. doi:10.21767/1791-809X.1000528

84. Yousaf HQ, Ali I, Sajjad A, Ilyas M. Impact of internal corporate social responsibility on employee engagement: a study of moderated mediation model. Int J Sci. 2016;30(5):226–243.

85. Singhal H, Rastogi R. Psychological capital and career commitment: the mediating effect of subjective well-being. Manage Decis. 2018;56(2):458–473. doi:10.1108/MD-06-2017-0579

86. Rūtelionė A, Šeinauskienė B, Nikou S, Lekavičienė R, Antinienė D. Emotional intelligence and materialism: the mediating effect of subjective well-being. J Consum Market. 2022;39:579–594. doi:10.1108/JCM-01-2021-4386

87. Kaczmarek ŁD, Bączkowski B, Enko J, Baran B, Theuns P. Subjective well-being as a mediator for curiosity and depression. Polish Psychol Bull. 2014;45(2):200–204. doi:10.2478/ppb-2014-0025

88. Hansen A, Buitendach JH, Kanengoni H. Psychological capital, subjective well-being, burnout and job satisfaction amongst educators in the Umlazi region in South Africa. SA J Human Resource Manage. 2015;13(1):1–9. doi:10.4102/sajhrm.v13i1.621

89. Kim H, Woo E, Uysal M, Kwon N. The effects of corporate social responsibility (CSR) on employee well-being in the hospitality industry. Int J Contemp Hosp Manage. 2018;30(3):1584–1600. doi:10.1108/IJCHM-03-2016-0166

90. Donia MB, Ronen S, Tetrault Sirsly C-A, Bonaccio S. CSR by any other name? The differential impact of substantive and symbolic CSR attributions on employee outcomes. J Bus Ethics. 2019;157(2):503–523. doi:10.1007/s10551-017-3673-5

91. Hur W-M, Moon T-W, Choi W-H. The role of job crafting and perceived organizational support in the link between employees’ CSR perceptions and job performance: a moderated mediation model. Curr Psychol. 2021;40(7):3151–3165. doi:10.1007/s12144-019-00242-9

92. Hameed Z, Khan IU, Islam T, Sheikh Z, Khan SU. Corporate social responsibility and employee pro-environmental behaviors. South Asian J Bus Stud. 2019;8(3):246–265. doi:10.1108/SAJBS-10-2018-0117

93. Raza A, Farrukh M, Iqbal MK, Farhan M, Wu Y. Corporate social responsibility and employees’ voluntary pro‐environmental behavior: the role of organizational pride and employee engagement. Corporate Soc Responsibil Environ Manag. 2021;28(3):1104–1116. doi:10.1002/csr.2109

94. Brennan EJ. Towards resilience and wellbeing in nurses. Br J Nurs. 2017;26(1):43–47. doi:10.12968/bjon.2017.26.1.43

95. Cosco TD, Howse K, Brayne C. Healthy ageing, resilience and wellbeing. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2017;26(6):579–583. doi:10.1017/S2045796017000324

96. DiCorcia JA, Tronick E. Quotidian resilience: exploring mechanisms that drive resilience from a perspective of everyday stress and coping. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35(7):1593–1602. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.04.008

97. Sandifer PA, Walker AH. Enhancing disaster resilience by reducing stress-associated health impacts. Front Public Health. 2018;373:145.

98. Lupe SE, Keefer L, Szigethy E. Gaining resilience and reducing stress in the age of COVID-19. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2020;36(4):295–303. doi:10.1097/MOG.0000000000000646

99. Richardson GE. The metatheory of resilience and resiliency. J Clin Psychol. 2002;58(3):307–321. doi:10.1002/jclp.10020

100. Southwick FS, Martini BL, Charney DS, Southwick SM. Leadership and resilience. In: Leadership Today. Springer; 2017:315–333.

101. Mahmood S, Shaari R, Sarip A. Sprituality and resilience effects on employee awareness and engagement in CSR: an overview and research agenda. J Adv Res Soc Behav Sci. 2018;12(1):35–44.

102. Fairlie P, Svergun O. The interrelated roles of CSR and stress in predicting employee outcomes. Work Stress Health. 2015:2015:6–9.

103. Arrogante O, Pérez-García A. El bienestar subjetivo percibido por los profesionales no sanitarios¿ es diferente al de enfermería de intensivos? Relación con personalidad y resiliencia [Is subjective well-being perceived by non-health care workers different from that perceived by nurses? Relation with personality and resilience]. Enfermería intensiva. 2013;24(4):145–154. doi:10.1016/j.enfi.2013.07.002

104. Kashyap SP, Kumar S, Krishna A. Role of resilience as a moderator between the relationship of occupational stress and psychological health. Indian J Health Wellbeing. 2014;5(9):4–12.

105. Doyle N, MacLachlan M, Fraser A, et al. Resilience and well-being amongst seafarers: cross-sectional study of crew across 51 ships. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2016;89(2):199–209. doi:10.1007/s00420-015-1063-9

106. Migliorini C, Callaway L, New P. Preliminary investigation into subjective well-being, mental health, resilience, and spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2013;36(6):660–665. doi:10.1179/2045772313Y.0000000100

107. Steptoe A, Deaton A, Stone AA. Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing. Lancet. 2015;385(9968):640–648. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61489-0

108. Brown S, Whichello R, Price S. The impact of resiliency on nurse burnout: an integrative literature review. Medsurg Nurs. 2018;27(6):349.

109. Yıldırım M, Arslan G. Exploring the associations between resilience, dispositional hope, preventive behaviours, subjective well-being, and psychological health among adults during early stage of COVID-19. Curr Psychol. 2020;2020:1–11.

110. Darvishmotevali M, Ali F. Job insecurity, subjective well-being and job performance: the moderating role of psychological capital. Int J Hosp Manage. 2020;87:102462. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102462

111. Chen C. The role of resilience and coping styles in subjective well-being among Chinese university students. Asia Pacific Educ Res. 2016;25(3):377–387. doi:10.1007/s40299-016-0274-5

112. Jiang Y, Ming H, Tian Y, et al. Cumulative risk and subjective well-being among rural-to-urban migrant adolescents in China: differential moderating roles of stress mindset and resilience. J Happiness Stud. 2020;21(7):2429–2449. doi:10.1007/s10902-019-00187-7

113. Shaikh BT. Private sector in health care delivery: a reality and a challenge in Pakistan. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2015;27(2):496–498.

114. Abbas R. 6 Facts about healthcare in Pakistan Pakistan, The Borgen Project; 2021. Available from: https://borgenproject.org/facts-about-healthcare-in-pakistan/.

115. Adnan M, Ahmad N, Scholz M, Khalique M, Naveed RT, Han H. Impact of substantive staging and communicative staging of sustainable servicescape on behavioral intentions of hotel customers through overall perceived image: a case of boutique hotels. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(17):9123. doi:10.3390/ijerph18179123

116. Awan K, Ahmad N, Naveed RT, Scholz M, Adnan M, Han H. The impact of work–family enrichment on subjective career success through job engagement: a case of banking sector. Sustainability. 2021;13(16):8872. doi:10.3390/su13168872

117. Peng J, Samad S, Comite U, et al. Environmentally specific servant leadership and employees’ Energy-specific pro-environmental behavior: evidence from healthcare sector of a developing economy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(13):7641. doi:10.3390/ijerph19137641

118. Fu Q, Cherian J, Ahmad N, Scholz M, Samad S, Comite U. An inclusive leadership framework to foster employee creativity in the healthcare sector: the role of psychological safety and polychronicity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(8):4519. doi:10.3390/ijerph19084519

119. Alam T, Ullah Z, AlDhaen FS, AlDhaen E, Ahmad N, Scholz M. Towards explaining knowledge hiding through relationship conflict, frustration, and irritability: the case of public sector teaching hospitals. Sustainability. 2021;13(22):12598. doi:10.3390/su132212598

120. Guan X, Ahmad N, Sial MS, Cherian J, Han H. CSR and organizational performance: the role of pro‐environmental behavior and personal values. Corporate Soc Responsibil Environ Manag. 2022. doi:10.1002/csr.2381

121. Daniel S. A-priori sample size calculator for structural equation models 2010. 2022.

122. Kuvaas B, Buch R, Dysvik A. Individual variable pay for performance, controlling effects, and intrinsic motivation. Motiv Emot. 2020;44(4):525–533. doi:10.1007/s11031-020-09828-4

123. Dedeoglu BB, Bilgihan A, Ye BH, Buonincontri P, Okumus F. The impact of servicescape on hedonic value and behavioral intentions: the importance of previous experience. Int J Hosp Manage. 2018;72:10–20. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.12.007

124. Turker D. Measuring corporate social responsibility: a scale development study. J Bus Ethics. 2009;85(4):411–427. doi:10.1007/s10551-008-9780-6

125. Smith BW, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Christopher P, Bernard J. The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. Int J Behav Med. 2008;15(3):194–200. doi:10.1080/10705500802222972

126. Lyubomirsky S, Lepper HS. A measure of subjective happiness: preliminary reliability and construct validation. Soc Indic Res. 1999;46(2):137–155. doi:10.1023/A:1006824100041