Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

Information Cocoons on Short Video Platforms and Its Influence on Depression Among the Elderly: A Moderated Mediation Model

Authors He Y , Liu D, Guo R, Guo S

Received 18 April 2023

Accepted for publication 19 June 2023

Published 3 July 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 2469—2480

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S415832

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Yiqing He,1 Darong Liu,2 Ruitong Guo,3 Siping Guo1

1School of Education, Guangzhou University, Guangzhou, People’s Republic of China; 2Department of Artificial Intelligence, Faculty of Computer Science and Information Technology, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; 3School of Education, Yunnan Minzu University, Kunming, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Ruitong Guo, Email [email protected]

Background: As the elderly increasingly engage with new media, particularly short video platforms, concerns are arising about the formation of “information cocoons” that limit exposure to diverse perspectives. While the impact of these cocoons on society has been investigated, their effects on the mental well-being of the elderly remain understudied. Given the prevalence of depression among the elderly, it is crucial to understand the potential link between information cocoons and depression among older adults.

Methods: The study examined the relationships between information cocoons and depression, loneliness, and family emotional support among 400 Chinese elderly people. The statistical software package SPSS was used to establish a moderated mediation model between information cocoons and depression.

Results: Information cocoons directly predicted depression among the elderly participants. Family emotional support moderated the first half and the second half of the mediation process, whereby information cocoons affected the depression of the elderly through loneliness. Specifically, in the first half of the mediation process, when the level of information cocoons was lower, the role of family emotional support was more prominent. In the second half of the process, when the level of family emotional support was higher, such support played a more protective role in the impact of loneliness on depression.

Discussion: The findings of this study have practical implications for addressing depression among the elderly population. Understanding the influence of information cocoons on depression can inform interventions aimed at promoting diverse information access and reducing social isolation. These results will contribute to the development of targeted strategies to improve the mental well-being of older adults in the context of evolving media landscapes.

Keywords: personalized recommendations, information cocoons, depression, loneliness, family emotional support

Introduction

With the rise of social media, a new mode of communication has emerged, namely short videos, which have altered the way in which people access information. According to the 2021 “Silver-Haired Population Economic Insight Report” released by Quest Mobile (https://www.questmobile.com.cn/research/report-new/115), the fastest growing group of short video users comprises those aged 60 and above. Notably, short videos have already penetrated over 80% of the elderly population. Once “digital refugees”, elderly people have gradually learned to use short video apps for social participation, expanding the scale of their use of the Internet. This has promoted the integration of the elderly into the digital world and the development of active aging. However, the personalised recommendation function of short video platforms may indirectly negatively affect older people’s mental health, such as by creating “information cocoons” that increase their loneliness and depression. At present, elderly people in China are still mainly supported by their families, such that family emotional support plays an important role in the mental health of Chinese older adults. Therefore, the potential role of family emotional support in reducing information cocoons and associated mental health problems among the elderly has high research value, especially in China.

Information Cocoons and Depression

The concept of information cocoons was proposed by Keith Sunstein, an American scholar. In his book Infotopia: How many minds produce knowledge, Sunstein1 argued that in the context of information communication, users focus on topics that interest them, creating a “personal daily newspaper”. that enables them to exclude or ignore other viewpoints and content.1 According to Sunstein, information cocoons creates an environment in which people only encounter voices that express opinions and ideas similar to their own. Such an environment—in which similar content is repeated and reinforced—is known as an “echo chamber”.2,3 Sunstein1 argued that echo chambers foster addiction to the reinforcement of a “false self” or myopic self-focus and prevent users from encountering heterogeneous people and opinions. This limits their information vision and hinders the all-round development of individual information in the long run.4,5

After retirement, elderly individuals have more leisure time at their disposal. In terms of information access, their social circles are transformed from an open system (albeit primarily focused on work) into a relatively closed system.6 Short video apps, known for their user-friendly interfaces and high entertainment value, have gained popularity among the elderly. Short videos have become their primary platform for Internet engagement and increasingly infiltrated their daily lives, influencing their media literacy and social relationships.7–9

To date, research has focused on the positive impact of digital integration on the lives of older adults, such as facilitating their social reintegration and overall life satisfaction, ultimately leading to lower levels of depression.10–13 However, research has overlooked the negative impact of the personalized recommendation function of short video platforms on the psychological well-being of older adults. Due to these platforms’ intelligent algorithms, older individuals may lack relevant experience in handling personalised content, resulting in a narrowed focus guided by their own interests and lacking access to diverse information.14,15 This disconnect from society restricts their exposure to alternative perspectives and new experiences, thereby increasing their feelings of loneliness and depression.16 Additionally, even when individuals have the same level of Internet access, there are content consumption differences between younger and older demographics.17 Younger individuals tend to prefer real-time short videos featuring trending news, online “hot topics”, and other popular content, while many older adults engage with and share misleading video content related to rumors, emotional and ethical issues, and health-related matters.18 Continuous exposure to negative news, misinformation, and negative comments on social media may contribute to heightened emotional distress and an increased likelihood of experiencing depression.19 Hence, this study hypothesises that the phenomenon of information cocoons in short videos can significantly predict higher levels of depression among older adults.

The Mediating Role of Loneliness

Loneliness is a negative subjective emotional experience, which is caused by the difference between the expected scope of social relationships and the actual scope of social relationships.20,21 Loneliness affects all age groups, but it is especially prevalent among the elderly.22

Although the integration of digital technology has introduced many elderly people to a “tech-savvy” lifestyle, it is important to note that the excessive use of short videos can create information cocoons, as defined above. Apart from causing depression, such cocoons may have other negative effects, such as intensifying feelings of loneliness among the elderly. While short video platforms showcase a vibrant online world that enables older adults to learn about new things,23–26 the lack of real-life interaction and communication on these platforms can make them feel isolated from the outside world.27 What older adults truly need is attention and care; the lack thereof can contribute to their sense of loneliness. In other words, elderly individuals may become immersed in information cocoons because they lack opportunities for social participation and to establish real connections in the physical world, thus diverting their energy towards short video apps.28 This will further exacerbate their feelings of loneliness. Therefore, this study hypothesises that information cocoons on short video apps can positively and significantly predict feelings of loneliness among older adults.

Feelings of loneliness can also have adverse effects on the overall well-being and psychological state of older individuals.29,30 Tomás et al31 found a negative correlation between loneliness and life satisfaction and a positive correlation between loneliness and depression among older adults. In a study of loneliness among elderly individuals in rural China, Liu et al32 found that loneliness not only directly exacerbated elderly people’s depressive symptoms but also indirectly affected their depression through self-identity. Therefore, this study hypothesises that feelings of loneliness are positively correlated with depression among older adults.

Information cocoons experienced by older adults often arise from factors such as limited technological skills, social resources, and access to information, which gradually isolate them within an information-deprived environment dominated by short videos. This leads to a shrinking social circle, reduced communication, and decreased connection with the outside world,33 ultimately forming a self-contained information cocoon. In such circumstances, elderly individuals often feel lonely and helpless, which frequently contributes to their feelings of depression. Therefore, this study also hypothesises that feelings of loneliness mediate the relationship between the information cocoons experienced by older adults and their depressive symptoms.

The Moderating Role of Family Emotional Support

“Family support” refers to the subjective and/or objective influence of various social relationships based on a family network organization.34 It refers mainly to the help that family members receive from individuals, which takes three main forms: economic support, life care and emotional support.35 Emotional support is an important part of family support. “Emotional support” refers to trust, empathy, love and care provided through verbal and nonverbal behaviours,36 including listening, companionship and words of encouragement and affirmation, such that those supported feel that they are cared for, respected and understood by others.37 To date, the concept of family emotional support has not been clearly defined. In this study, family emotional support is defined as a kind of intangible support whereby family members give care and companionship to the elderly, making them feel valued, respected and cared for.

According to a Chinese saying, “When there is an old person in the family, it is like having treasure there.” In traditional Chinese culture, family is highly valued and the elderly are regarded as an important part of the family.38 Against this cultural background, family emotional support is not only a necessary condition for elderly people’s well-being and their main source of social support; it also reflects social values and traditional principles.39 Accordingly, in Chinese society, Chinese families tend to provide for the aged at home, and older people expect to be supported and cared for by their families.40 Studies41,42 have shown that family emotional support is an important factor in maintaining older people’s physical health and psychological well-being. With the care and love of family members, the elderly can better cope with the pressures and challenges in life.

This study argues that family emotional support plays an important role in tackling information cocoons among the elderly. Elderly people trapped in information cocoons may feel lonely and isolated because of a lack of real-life social, cultural and technical experience, and then transfer their spiritual needs to short video apps. Family members can provide support and a series of resources to help the elderly engage in more social activities and integrate with the community, find more opportunities for real-life social interaction, provide others with emotional support, feel less lonely and isolated, and properly integrate into today’s digital society.43 Therefore, this study assumes that family emotional support plays a moderating role in the information cocoons and loneliness of the elderly.

In addition, Wu & Zhang’s26 study have shown that family emotional support can increase elderly people’s social contact and participation and ensure that they feel cared for and respected. Sharing their troubles with their families and obtaining comfort and support from relatives can alleviate older adults’ loneliness. Such emotional exchanges can help the elderly maintain a positive emotional state and relieve their depression. Therefore, this study also argues that family emotional support plays a moderating role in the loneliness and depression of the elderly.

Hypotheses

In sum, this study constructs a moderated mediation model (Figure 1) based on the following research hypotheses.

H1: There are significant positive correlations between information cocoons, loneliness and depression among elderly people. Family emotional support is negatively correlated with information cocoons, loneliness and depression. H2: Information cocoons positively and significantly predict depression among the elderly. H3: Loneliness mediates the relationship between information cocoons and depression among the elderly. H4: Family emotional support moderates the first half and the second half of the mediation process in which information cocoons increase the depression of the elderly through loneliness.

|

Figure 1 A moderated mediation model. |

Methods

Participants and Procedure

In this study, a cluster sampling method was adopted to select elderly people over 60 years old with clear cognition, barrier-free speech and the ability to communicate with others. in Guangdong province, China. The exclusion criteria included the following: severe dementia or other disability, emotional instability, and inability to complete the questionnaire. Paper copies of the questionnaire were administered. Questionnaires were excluded as invalid if responses were incomplete, if the same answers were chosen for all items or if the answers on the questionnaire are logically inconsistent and incoherent. A total of 425 questionnaires were distributed and 400 returned questionnaire copies were valid, giving a recovery rate of 94.1%. Two hundred and six male respondents (51.5%) and 194 female respondents (48.5%) were surveyed, with an average age of 65.49 years and a standard deviation of 2.21.

A consent form was administered before the formal questionnaire survey to ensure that the needs of the subjects were fully met, ensure that each subject was aware that their participation was voluntary, and emphasize that the survey results would be kept confidential. Some subjects might have been unable to fill in the questionnaire independently, due to their illiteracy or inability to hold a pen. To ensure the quality of this data, students majoring in psychology repeated and explained the content of the questionnaire to the subjects to ensure that they fully understood the questions and gave true answers. For some difficult questions, the researchers provided a unified explanation after professional discussion to ensure the consistency of all of the explanations.

Measures

Short Video Information Cocoons Scale

This study adopted the Short Video Information Cocoons Scale developed by Guo.44 This scale has 16 items and four dimensions: personalized recommendations, immersion experience, leaving the echo chamber and active information processing. A 3-point Likert scale is used for scoring; each item scores 1–3 points, corresponding to answers of “No”, “Neutral” and “Yes”. The final score is converted from the initial score; that is, the final score for items initially given 2 points or 3 points is 1 point, and the final score for an item initially given 1 point is 0 points. The higher the total score, the higher the level of information cocoons among the elderly. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.86.

De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale (DJGLS)

This study adopted the Spanish version of the DJGLS, translated into Chinese by Yang and Guo.45 This scale includes 11 items and two dimensions, namely a social loneliness dimension and an emotional loneliness dimension. A 3-point Likert scale is used for scoring; each item scores 1–3 points, corresponding to answers of “No”, “Neutral” and “Yes”. The higher the total score, the higher the level of loneliness of the elderly. The final score is the converted score; that is, the final score for items initially awarded 2 points or 3 points is 1 point, and the final score for an item initially awarded 1 point is 0 points. A total score of 0–2 indicates no loneliness, 3–8 indicates moderate loneliness, 9–10 indicates severe loneliness, and 11 indicates extreme loneliness. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.79.

Self-Rating Scale of Family Emotional Support

In this study, Zou’s21 Self-rating of Family Emotional Support Scale was adopted, with 15 items in total. This scale has a two-level scoring system, with “Yes” as 1 point and “No” as 0 point. The higher the score, the more emotional support the family provides. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.83.

Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

The present study used the Patient Health Questionnaire—Depression Scale translated and revised by Zhang et al46 to measure the severity of depression of the participants. The scale was strictly compiled according to the standards of the DSM-IV. It includes nine items and is scored on a 4-point scale (0 = “Not at all” to 3 = “Almost every day”). The total scores for the nine items are summed to obtain the total score for the PHQ-9. The higher the PHQ-9 score, the more serious the depressive symptoms. A score ≥ 5 means that depressive symptoms are present. A score of 5–9 points indicates a mild depressive tendency; 10–14 a moderate depressive tendency; 15–19 a moderately severe depressive tendency; and 20–27 a severe depressive tendency. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.89.

Results

Test for Common Method Bias

The use of self-report measures may have produced common method bias.47 Therefore, Harman’s one-factor test was applied to test for common method bias, examine the factor analysis of the data, and select the extraction method with an eigenvalue greater than 1. Sixteen factors with eigenvalues greater than one were extracted, which explained 24.61% of the total variance; the explanatory variables of the first principal component factor accounted.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

The results of correlation analysis in Table 1 show that every two variables were significantly correlated. Information cocoons and loneliness were positively and significantly correlated with depression; and family emotional support was negatively and significantly correlated with information cocoons, loneliness and depression. There was a significant positive correlation between information cocoons and loneliness.

|

Table 1 Description Statistics and Correlation Analysis |

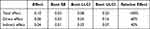

Test of Mediating Effect of Loneliness

In this study, Model 4 of SPSS PROCESS 3.5 was used to test the mediating effect of loneliness on the relationship between information cocoons and depression. The results in Table 2 show that after controlling for gender and age, the 95% confidence interval of the direct influence of information cocoons on depression was [0.05, 0.16], and the 95% confidence interval of the mediation effect of loneliness was [0.03, 0.07]. Both the direct effect and the indirect effect were significant, and the indirect effect accounted for 40%.

|

Table 2 The Mediating Role of Loneliness in the Relationship Between Information Cocoons and Depression |

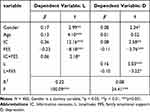

Test of the Moderating Effect of Family Emotional Support

In this study, Model 58 of SPSS PROCESS 3.5 was used to test the moderating effect of family emotional support, control for gender and age, standardise the predictive variables, and test the moderated mediation model.48

As shown in Table 3, for the dependent variable of loneliness, information cocoons had a positive predictive effect on loneliness, family emotional support had a negative predictive effect on loneliness, and the interaction between information cocoons and family emotional support had a significant impact on loneliness. In addition, family emotional support moderated the influence of information cocoons on loneliness. For the dependent variable of depression, loneliness had a positive predictive effect. After adding family emotional support, family emotional support negatively predicted depression. The interaction between loneliness and family emotional support had a significant impact on depression, and family emotional support also moderated the influence of loneliness on depression. In sum, family emotional support moderated the first half and the second half of the mediation model, and the moderated mediation model was validated.

|

Table 3 The Mediating Effect of Information Cocoons on Depression |

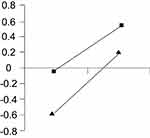

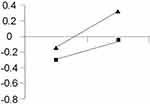

Through further simple slope analysis, we examined the trend of adjustment, divided family emotional support into a high group (M + 1SD) and a low group (M – 1SD), and made a simple slope test chart between family emotional support, depression and information cocoons among the elderly.

In the first half of the model, family emotional support moderated the influence of information cocoons on loneliness (Figure 2 and Table 4). Specifically, regardless of the level of family emotional support, information cocoons positively predicted loneliness; that is, when the level of information cocoons was low, family emotional support played a greater role, while when the level of information cocoons was high, the moderating role of family emotional support became weak.

|

Table 4 The Moderating Effect of Family Emotional Support Between Information Cocoons and Loneliness |

In the second half of the model, family emotional support moderated the influence of loneliness on depression (Figure 3 and Table 5). Specifically, regardless of the level of family emotional support, loneliness positively predicted depression. When the level of family emotional support was high, it played a more protective role in the influence of loneliness on depression; when the level of family emotional support was low, it exerted a less protective effect on the influence of loneliness on depression.

|

Table 5 The Moderating Effect of Family Emotional Support Between Loneliness and Depression |

Discussion

Based on the average questionnaire scores of the sampled participants, the phenomenon of short video information cocoons among the elderly is severe, with moderate levels of loneliness, weak family emotional support and a tendency for depression. Possible reasons for these results are that the social circle of the elderly has shrunk because of retirement, their children have left home to work, their family emotional support has weakened, and their sense of social isolation has gradually increased.49,50 In these circumstances, the elderly may obtain information and entertainment through short videos and other media; however, long-term virtual social interaction cannot meet their need for family and friendship. Instead, it will aggravate their loneliness and depression. In addition, vulgar, false, violent and other negative content on short video platforms may threaten the physical and mental health of the elderly and cause emotional fluctuations and psychological problems, such as depression.51 Improving the information literacy of the elderly is a key strategy for addressing the problem of information cocoons. With their limited degree of Internet cognition, the proficiency of the elderly in using smartphones is far lower than that of young people, and they often lack the ability to distinguish between true and false information and properly use information technology, which deepens their dependence on short video platforms.52,53 Based on the characteristics of the elderly and their information literacy needs, the government and other institutions should organise volunteer guidance, community free training and other public welfare activities. The training content should cover information identification, information acquisition skills, information fraud prevention and other relevant knowledge to address elderly people’s knowledge and cognitive limitations, cultivate their anti-fraud awareness and ability, and fundamentally eliminate the negative impact of information cocoons on this population.

The correlation analysis results showed that information cocoons, loneliness and depression were all positively correlated, and they were each negatively correlated with family emotional support (consistent with Hypothesis 1). This shows that the more serious the problem of information cocoons among the elderly, the deeper the loneliness and depression. When using short video platforms, the elderly often choose to engage with information that they are already familiar with, only pay attention to the short video content recommended by personalised algorithms, and regard their own cognition as truth, instead of expanding their information and social circle.54,55 This narrows their cognitive focus and social circle, reduces their opportunities for communication with real-life society, weakens their social ties and increases their loneliness. In addition, information cocoons may prevent the elderly from obtaining new information, new experiences and new feelings, and inhibit them from fully understanding and exploring life.56 This may lead the elderly to feel that life is meaningless, thus increasing their depression. When using short video platforms, the elderly may also face technical obstacles or information overload, and they may also encounter online fraud and false information,57 further aggravating their anxiety. Such negative emotions may cause the elderly to feel depressed. However, family emotional support was found to be negatively correlated with the other variables, showing that strengthening family members’ care and support for the elderly can reduce certain negative effects of information cocoons on older adults. Therefore, the creators of short video platforms should improve their information quality, enrich their information content, and strengthen their information veracity58 to break down information cocoons among the elderly, thus alleviating their loneliness and depression.

The results of the mediation analysis conducted in this study suggest that information cocoons not only have a significant direct effect on the depression of the elderly, but also have an indirect effect on the depression of the elderly through loneliness, which plays a partial mediating role between information cocoons and depression (consistent with Hypotheses 2 and 3). Specifically, elderly individuals who are troubled by information cocoons do not form positive real-life social relationships, which leads to the narrowing of their social circle and makes it difficult for them to obtain sufficient social support and emotional connections,59 which often leads to loneliness. Loneliness is a negative emotion. Long-term and worsening loneliness may lead to depression in the elderly.60 Therefore, society should provide diverse opportunities for the elderly to establish realistic ties with family, friends and community residents. Communities should organise various social activities, such as group sports, arts and crafts courses, and voluntary activities, to provide diverse social opportunities for the elderly, communicate with them as much as possible, and provide appropriate attention and companionship. This will help alleviate older adults’ loneliness and depression.

The results of the moderation analysis indicate that when the level of information cocoons among the elderly is low, family emotional support plays a greater role in alleviating loneliness (consistent with Hypothesis 4). When information cocoons among the elderly is less serious, the emotional support and care of family members may shift elderly people’s attention away from short videos, enabling them to avoid and escape information cocoons created by short video apps. However, when the level of information cocoons among the elderly is high, the role of family emotional support in regulating loneliness weakens. This may be because information cocoons are themselves a function of social isolation.61 If the elderly are deeply affected by information cocoons, they will more frequently engage with short video media information, leading to reduced interaction and communication with others, and thus loneliness. Even if the level of family emotional support is high, it cannot completely replace social contact and interaction between the elderly and society and others. Limited social interaction will deepen the loneliness of the elderly.62 Therefore, in addition to paying attention to family emotional support, we should treat social support as a regulating variable. Thus, we should encourage the elderly to actively participate in social activities, improve media literacy, establish contact networks with relatives and friends, and so on, to strengthen their social support. This will alleviate the loneliness of the elderly and help them better adapt to today’s digital society and modern lifestyles.

The results of the moderation analysis suggest that when the level of family emotional support is high, it plays a greater protective role in the influence of loneliness on depression. When the level of family emotional support is low, it plays a less protective role in the influence of loneliness on depression (consistent with Hypothesis 4). Some studies39,63,64 have shown that family emotional support can reduce loneliness and depression among the elderly. Older people who use new media short video platforms often lack real emotional support. Unlike traditional social practices, new media platforms such as short videos cannot offer face-to-face interaction and emotional communication or enable older adults to establish deep interpersonal relationships or get real emotional support. This may cause the elderly to feel lonely, helpless and uncared for, thus increasing their depression. In China, family support is the main form of social support for elderly people, all of whom expect to be taken care of by their children. Therefore, to provide sufficient emotional support, the children of aged parents in China should keep in touch and share important moments in life with their parents through short video platforms. Children should also educate their elderly parents in how to avoid the risks of online fraud on short video platforms, which will help tackle the problem of information cocoons created by digital society and enable older adults to enjoy the convenience and happiness brought by digital technology.

Limitations and Suggestions

This study has three main shortcomings. First, the use of a self-report scale may have exerted a certain social approval effect, leading the subjects to give more positive answers when answering questions. Second, the sample of subjects in this study was not representative of individual demographic variables, which may have affected the results for the variables. Third, this study discussed only the mediating role of loneliness and the moderating role of family emotional support in the influence of information cocoons on depression. Other mediating and moderating paths may be worth exploring.

To address the limitations of this study, several suggestions can be considered for future research. First, employing multiple assessment tools, such as objective observations and physiological measures, can mitigate the social approval effect associated with self-report scales. Second, increasing the sample size and ensuring representative demographic variables would enhance the generalisability of the findings. Third, exploring alternative mediating and moderating pathways in the relationship between information cocoons and depression, such as social support or individual resilience, would provide a more comprehensive understanding. Lastly, employing a mixed-methods research design, conducting longitudinal studies, and diversifying samples across different cultural backgrounds would further enrich the field.

Conclusions

This study provides valuable insights into the influence of information cocoons on depression among the elderly through a moderated mediation model. The findings reveal that information cocoons on short video apps directly predict depression in older adults. Additionally, loneliness and family emotional support play crucial roles in mediating the relationship between information cocoons and depression. Specifically, in the first half of the mediation process, when information cocoons is at a lower level, higher levels of family emotional support play a greater role in reducing loneliness. However, as the level of information cocoons increases, the moderating effect of family emotional support on loneliness decreases. In the latter half of the process, higher levels of family emotional support offer greater protection against the impact of loneliness on depression, whereas lower levels of family emotional support provide less protective effects. These findings highlight the significance of addressing the problem of information cocoons and promoting adequate family emotional support as potential strategies to alleviate depression and improve the well-being of the elderly population.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2023M730772).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Sunstein CR. Infotopia: How Many Minds Produce Knowledge. UK: Oxford University Press; 2006.

2. Chen CF, Shi W. Technical interpretation and value discussion of personalized news recommendation algorithm. Chin Edit J. 2018;10:9–14.

3. Yang G, She JL. News visibility, user activeness and echo chamber effect on news algorithmic recommendation: a perspective of the interaction of algorithm and users. Jl Res. 2020;2:102–118.

4. Fan M, Huang Y, Qalati SA, Shah SMM, Ostic D, Pu Z. Effects of information overload, communication overload, and inequality on digital distrust: a cyber-violence behavior mechanism. Front Psychol. 2021;12:643981. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.643981

5. Guess A, Nyhan B, Lyons B, Reifler J. Avoiding the echo chamber about echo chambers. Knight Found. 2018;2(1):1–25.

6. Zhu SS, Sun C. Community friendly service platform for elderly followed by the activity theory. Packag Engin. 2022;43(14):129–138. doi:10.19554/j.cnki.1001-3563.2022.14.015

7. Du P, Han WT. Internet and life of older adults: challenges and opportunities. Popul Res. 2021;45(3):3–16.

8. Neves BB, Franz RL, Munteanu C, Baecker R. Adoption and feasibility of a communication app to enhance social connectedness amongst frail institutionalized oldest old: an embedded case study. Inf Commun Soc. 2018;21(11):1681–1699. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2017.1348534

9. Nimmanterdwong Z, Boonviriya S, Tangkijvanich P. Human-centered design of mobile health apps for older adults: systematic review and narrative synthesis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2022;10(1):e29512. doi:10.2196/29512

10. Ang S, Chen TY. Going online to stay connected: online social participation buffers the relationship between pain and depression. J Gerontol. 2019;74(6):1020–1031. doi:10.1093/geronb/gby109

11. Jiang S, Jiang CX, Ren Q. The digital inclusion, social capital, and mental health of older Chinese adults: Empirical Evid ence from the China Longitudinal Aging Social Survey(CLASS). Govern Stud. 2022;5:25–34+125.

12. Nakagomi A, Shiba K, Kondo K, Kawachi I. Can online communication prevent depression among older people? A longitudinal analysis. J Appl Gerontol. 2022;41(1):167–175. doi:10.1177/0733464820982147

13. Wallinheimo AS, Evans SL. More frequent internet use during the COVID-19 pandemic associates with enhanced quality of life and lower depression scores in middle-aged and older adults. Healthcare. 2021;9(4):393. doi:10.3390/healthcare9040393

14. Li LF, Zhang GL. Generation mechanism and governance path of “information cocoons” Effect in Algorithm Era——Based on the perspective of information ecology theory. E-Government. 2022;9:51–62.

15. Ng R, Indran N. Granfluencers on TikTok: factors linked to positive self-portrayals of older adults on social media. PLoS One. 2023;18(2):e0280281. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0280281

16. Yu GM, Fang KR. Will algorithmic content delivery result in information cocoons? A positive analysis based on media diversity and trust in information source. Shandong Soc Sci. 2020;11:169–174.

17. Zhao YC, Zhao M, Song S. Online health information seeking behaviors among older adults: systematic scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(2):e34790. doi:10.2196/34790

18. Zhuang X. The Urban elderly’s contact with and judgement of health information on wechat. J Nanjing Norm Univ. 2019;6:112–122. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1001-4608.2019.06.011

19. Gu X, Obrenovic B, Fu W. Empirical study on social media exposure and fear as drivers of anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability. 2023;15(6):5312. doi:10.3390/su15065312

20. Masi CM, Chen HY, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2011;15(3):219–266. doi:10.1177/1088868310377394

21. Zou JY. The Effect Mechanism of Socioeconomic Status on Loneliness in the Elderly: the Mediating Role of Perceived Social Support and Sleep Quality [Dissertation]. Taiyuan: Shanxi Medical University; 2022.

22. Lim MH, Eres R, Vasan S. Understanding loneliness in the twenty-first century: an update on correlates, risk factors, and potential solutions. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2020;55:793–810. doi:10.1007/s00127-020-01889-7

23. Hülür G, Macdonald B. Rethinking social relationships in old age: digitalization and the social lives of older adults. Am Psychol. 2020;75(4):554–566. doi:10.1037/amp0000604

24. Locsin RC, Soriano GP, Juntasopeepun P, Kunaviktikul W, Evangelista LS. Social transformation and social isolation of older adults: digital technologies, nursing, healthcare. Collegian. 2021;28(5):551–558. doi:10.1016/j.colegn.2021.01.005

25. Quittschalle J, Stein J, Luppa M, et al. Internet use in old age: results of a German population-representative survey. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(11):e15543. doi:10.2196/15543

26. Wu L, Zhang LQ. The levels and functions of digital technology in relieving the spiritual loneliness of the elderly. J Cent Chin Norml Univ. 2022;61(1):182–188.

27. He Q, Shen JR. Fraud Vulnerability of the Elderly: concept, theories, and measurements. Chin J Appl Psychol. 2020;26(3):208–218.

28. Esain I, Gil SM, Duñabeitia I, Rodriguez-Larrad A, Bidaurrazaga-Letona I. Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on physical activity and health-related quality of life in older adults who regularly exercise. Sustainability. 2021;13(7):3771. doi:10.3390/su13073771

29. Kim JH. Productive aging of Korean older people based on time use. Soc Sci Med. 2019;229:6–13. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.04.020

30. Lee SL, Pearce E, Ajnakina O, et al. The association between loneliness and depressive symptoms among adults aged 50 years and older: a 12-year population-based cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(1):48–57. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30383-7

31. Tomás JM, Pinazo‐Hernandis S, Oliver A, Donio‐Bellegarde M, Tomás‐Aguirre F. Loneliness and social support: differential predictive power on depression and satisfaction in senior citizens. J Community Psychol. 2019;47(5):1225–1234. doi:10.1002/jcop.22184

32. Liu HR, Shang XH, Wang Y, Kou S. Influence of loneliness on rural elderly people’s depression: The mediating role of self-identity. J Health Psychol. 2022;11:1607–1611.

33. Hu Z, Lin X, Chiwanda Kaminga A, Xu H. Impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on lifestyle behaviors and their association with subjective well-being among the general population in mainland China: cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(8):e21176. doi:10.2196/21176

34. Zhao H, Liu RF, Shi HJ, Zuo PX. Impact of the family support system on breastfeeding: a literature review. Mod Prev Med. 2018;45(7):1235–1238.

35. Ci QY, Ning WW. Research on Social Support of the Old-age in Poverty in Response to Weakening Family Support. Chin J Popul Sci. 2018;4:68–80.

36. Zhou YH. Research on the Intervention of Social Work to Enhance the Family Emotional Support of Elderly in Nursing Home [Dissertation]. Kunming: Yunnan University; 2020.

37. Du M. The Influence of social support on the mental health of the elderly. Popul Soc. 2017;33(4):12–19. doi:10.14132/j.2095-7963.2017.04.002

38. Zhang H. Research on the Construction of Modern Family Style in the Practice of Socialist Core Values [Dissertation]. Wuhan: Wuhan Polytechnic University; 2019.

39. Chen JY, Fang Y, Zeng YB. A study on the impact of diversified social involvement and family support on the mental health of elderly people in China. Chin J Health Policy. 2021;14(10):45–51. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1674-2982.2021.10.007

40. Cai M, Zhang YG, Xie XQ, Wu SY. Elderly people’s pension willingness and influencing factors of choosing home-based care of population aged 60 and above. Chin J of Hospital Stat. 2021;28(4):351–356. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1006-5253.2021.04.014

41. Banerjee D, D’Cruz MM, Rao TS. Coronavirus disease 2019 and the elderly: focus on psychosocial well-being, agism, and abuse prevention–An advocacy review. J Geriatr Mental Health. 2020;7(1):4–10. doi:10.4103/jgmh.jgmh_16_20

42. Suzuki Y, Maeda N, Hirado D, Shirakawa T, Urabe Y. Physical activity changes and its risk factors among community-dwelling Japanese older adults during the COVID-19 epidemic: associations with subjective well-being and health-related quality of life. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(18):6591. doi:10.3390/ijerph17186591

43. Sen K, Prybutok G, Prybutok V. The use of digital technology for social wellbeing reduces social isolation in older adults: a systematic review. SSM Popul Health. 2022;17:101020. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.101020

44. Guo R. An Empirical Research on Information Cocoon Effect of Short Video Platform Based on Algorithm Recommendation [Dissertation]. Jinan: Shandong University; 2022.

45. Yang B, Guo LL. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale. Chinese Gen Pract. 2019;22(33):4110–4115. doi:10.12114/j.issn.1007-9572.2019.00.319

46. Zhang YL, Liang W, Chen ZM. Validity and reliability of patient health questionnaire-9 and patient health questionnaire-2 to screen for depression among college students in China. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2013;5(4):268–275. doi:10.1111/appy.12103

47. Zhou H, Long LR. Statistical remedies for common method biases. Adv Psychol Sci. 2004;12(6):942–950. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1671-3710.2004.06.018

48. Wen ZL, Ye BJ. Different methods for testing moderated mediation models: competitors or backups. Acta Psychol Sin. 2014;46(5):714–726. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1041.2014.00714

49. Kim BJ, Kihl T. Suicidal ideation associated with depression and social support: a survey-based analysis of older adults in South Korea. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):1–9. doi:10.1186/s12888-021-03423-8

50. Sarkar SM, Dhar BK, Crowley SS, Ayittey FK, Gazi MAI. Psychological adjustment and guidance for ageing urban women. Ageing Int. 2023;48:1–9. doi:10.1007/s12126-021-09467-1

51. Zhu HT, Li SX, Gao QQ. Study on influencing factors of the formation of information cocoon among middle-aged people. J Zheng Instit Aeronaut Indust Manag. 2022;40(1):75–81. doi:10.19327/j.cnki.zuaxb.1007-9734.2022.01.009

52. Eliseo MA, Oyelere SS, da Silva CA, et al. Framework to creation of inclusive and didactic digital material for elderly. 2020.

53. Zeng YL, Liang XY, Han SX. Practice and enlightenment of American public libraries’ digital literacy education. Doc Inf Knowl. 2022;38(6):21–37. doi:10.13366/j.dik.2021.06.021

54. Choudrie J, Banerjee S, Kotecha K, Walambe R, Karende H, Ameta J. Machine learning techniques and older adults processing of online information and misinformation: a covid 19 study. Comput Human Behav. 2021;119:106716. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2021.106716

55. Meng R. Weakening of elder rights in digital times and its legal measures: taking feasible capability as an analytical framework. Stud Soc Chine Character. 2023;4(5–6):143–153.

56. Zhang DW, Xie XZ. Empirical research on the mechanism of public health emergency information seeking behavior among middle-aged and elderly people in rural areas. Libr Inf Sci Res. 2020;64(15):194–203. doi:10.13266/j.issn.0252-3116.2020.15.024

57. Murthy S, Bhat KS, Das S, Kumar N. Individually vulnerable, collectively safe: the security and privacy practices of households with older adults. Proc ACM Hum. 2021;5(CSCW1):1–24. doi:10.1145/3449212

58. Tu Z, Wang Y, Birkbeck N, Adsumilli B, Bovik AC. UGC-VQA: benchmarking blind video quality assessment for user generated content. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2021;30:4449–4464. doi:10.1109/TIP.2021.3072221

59. Zhang K, Kim K, Silverstein NM, Song Q, Burr JA. Social media communication and loneliness among older adults: the mediating roles of social support and social contact. Gerontologist. 2021;61(6):888–896. doi:10.1093/geront/gnaa197

60. Chen L, Alston M, Guo W. The influence of social support on loneliness and depression among older elderly people in China: coping styles as mediators. J Community Psychol. 2019;47(5):1235–1245. doi:10.1002/jcop.22185

61. Sima Y, Han J. Online carnival and offline solitude:“information cocoon” effect in the age of algorithms. In:

62. Dahlberg L, McKee KJ, Frank A, Naseer M. A systematic review of longitudinal risk factors for loneliness in older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2022;26(2):225–249. doi:10.1080/13607863.2021.1876638

63. Li C, Jiang S, Zhang X. Intergenerational relationship, family social support, and depression among Chinese elderly: a structural equation modeling analysis. J Affect Disord. 2019;248:73–80. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2019.01.032

64. Tsai HH, Cheng CY, Shieh WY, Chang YC. Effects of a smartphone-based videoconferencing program for older nursing home residents on depression, loneliness, and quality of life: a quasi-experimental study. BMC Geriatr. 2019;20(1):1–11. doi:10.1186/s12877-020-1426-2

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.