Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 15

Inclusive Leadership and Employee Proactive Behavior: A Cross-Level Moderated Mediation Model

Authors Chang PC, Ma G , Lin YY

Received 3 March 2022

Accepted for publication 14 June 2022

Published 14 July 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 1797—1808

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S363434

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Po-Chien Chang, Guangya Ma, Ying-Yin Lin

School of Business, Macau University of Science and Technology, Macau, China

Correspondence: Ying-Yin Lin, School of Business, Macau University of Science and Technology, Taipa, Macau, 999078, China, Tel +853 63976801, Email [email protected]

Purpose: The proactive behavior of employees is one of the key determinants of organizational development in a rapidly changing business environment. While much attention has been paid to the antecedents of employees’ proactive behavior, little is known about the mechanisms that influence their psychological state and work behavior. The aim of this research is to investigate the relationship between inclusive leadership (IL) and proactive behavior, along with mediating role of employee trust and the moderating role of procedural justice climate.

Methods: The data were collected from 40 independent project teams from 30 companies in China, and the hypotheses were tested on 304 available samples, followed by the null model to conduct the cross-level regression analysis.

Results: The results indicated that IL significantly affects the employee proactive behavior, in which employee trust played a mediating role. Moreover, procedural justice climate respectively moderates the positive relationship between IL and employee proactive behavior, and the positive relationship between IL and employee trust.

Conclusion: IL not only provides emotional support to increase employee trust but also inspires subordinates with a non-active personality to take initiative. Team-oriented organizational structures should promote procedural justice measures to create a trusting and fair work environment that more effectively furthers the effectiveness of IL on positive work behaviors of employees.

Keywords: inclusive leadership, proactive behavior, employee trust, procedural justice climate

Introduction

Can inclusiveness of leader fuel employee proactivity and what strategies organizations should develop to boost it? The research investigates the role of inclusive leadership (IL) and organization contextual strategy on employees’ proactive behavior. As global competition intensifies, the use of teams has increased dramatically to quickly respond to constantly changing task requirements and emergent technologies. On the one hand, this team-oriented organizational strategy is characterized by dynamic diversification, often consisting of cross-departmental and cross-professional project teams.1 On the other hand, practically, the diversity and dynamics of a team-oriented organizational structure often weaken the trust and belongings of employees in the workplace, which is not conducive to the full involvement of employees and further damages group processes and outcomes. At this time, companies not only need managers to effectively lead the team, but also urgently improve the proactive behavior of employees2 to actively implement corporate strategies, enhance sustainable viability, and achieve superior performance. The proactive behavior of employees is obviously a key determinant of organizational development and improving company performance.3 Therefore, how to motivate employees to take initiative has become a common concern of both academics and practitioners.4

Based on the model of proactivity proposed by Parker, a large number of scholars have supplemented antecedents and mechanisms of proactive behavior from two aspects- individual differences and contextual factors.4 First, much of this work has emphasized a proactive personality as an important antecedent for taking the initiative, including motivation and goal generation,5 desire for control,6 self-efficacy,7 learning, knowledge, skills, and abilities.8,9 Second, other work argues that while positive personality is a crucial predictor of employee proactive behavior at the individual level, contextual factors tend to affect employee behavior more directly in the workplace, such as social environment,10 support from leaders and organizations,11 fairness of distribution and procedure.12,13

Leaders directly or indirectly influence subordinates’ active behavior by stimulating their work motivation or influencing the work environment atmosphere.14 Current research reveals that goal-oriented leadership, such as transformational leadership and empowering leadership, plays a significant role to improve employee’s proactive behavior,15 it is not surprising because the motivational state of such leadership is to set a challenging goal to push subordinates to take initiatives. But practically the diversity and dynamics of team-oriented organizational structure often weaken the trust and belongings of employees in the workplace which is not conducive to the full involvement of employees, and further damages group processes and outcomes.16,17 IL performs in a different style by inviting subordinates to participate in decision-making, appreciating their uniqueness, encouraging their contributions, and tolerating their failures, which positively impact employees’ psychological state and work behavior results.1,14,18 However, scant attention has been paid to understanding the role of IL, and how related mechanisms, such as contextual climate, enable the effective functioning of diverse workgroups.17

Drawn upon conservation of resources (COR) theory, employees regard leaders as a favorable resource.19 Characteristics of inclusive leadership-openness, fairness, and tolerance create good conditions to improve subordinators’ belongingness and psychological safety.17 This implies that when the subordinates recognize that the leader cares more about themselves, which would close the relationship with the leader, thereby increasing trust in leaders. Employee trust is generated by the active interaction between employees and leaders, which is a highly directional psychological state, which further affects a series of perceptions, attitudes, and behavior of employees.20,21 Accordingly, this research infers that to obtain more support (external resources) from leaders, employees will transform their trust in leaders into positive attitudes and extra efforts (internal resources).22 Hence, this study expects that employee trust might mediate the relationship between inclusive leadership and employees’ proactive behavior. Moreover, research indicates that the consistency of contextual and personal factors can help motivate people to be more proactive.21,23 Although prior studies have examined various contextual conditions at the individual level, such as work pressure and interpersonal relationships,24,25 little is known about the conditions under which organizational climate can influence the relationship between IL and individual behavior.17 Therefore, it is meaningful that this study considers the interaction of organizational climate between IL and proactive behavior.

The contribution of this research to the literature is threefold. First, we develop a cross-level moderated mediating model to reveal the influence mechanism of IL on proactive behavior. Secondly, we expand our knowledge of IL by explaining the role of employee trust in the superior-subordinate relationship. Finally, we respond to the call of Randel et al to study contextual factors at the organizational level by identifying the impact of procedural justice climate.17

Theory and Hypothesis

Inclusive Leadership and Employee Proactive Behavior

Inclusive leadership (IL) is a distinct style of relational leadership, facilitating subordinate proactive behavior by providing a psychologically safe working atmosphere.26 First, inclusive leaders provide support, encourage speaking up, and appreciate the contributions of subordinates, thereby enhancing the collective belongingness and the psychological safety of employees.27,28 Second, IL demonstrates treatment of fairness and justice via openness, availability, and accessibility when interacting with subordinates, which convinces employees that their organization is committed to involving all employees in the operation of the organization.29 These positive interactive relationships inclusive leaders provide would bring together the final employees’ attitude and active behavior, such as voice,18 innovation,30 taking charge,31,32 self-efficacy,33 and creativity.34

Besides, according to proactive motivation theory, the interaction between individual differences and the corresponding environmental context generates three pathways to influence motivation states and active behavior.4 First, subordinates feel they can do it, even to improve the poor working conditions and problems they encounter instead of passively adapting to the status quo because the IL openness encourages employees to express interests, needs, and expectations, invite them to participate in decision-making, and appreciate their contributions, which enhance their self-efficacy.7,33 Second, the availability of inclusive leaders makes employees feel that the benefits and rewards they get are consistent with their effort goals, which enhances the proactive motivation of reasons do. Inclusive leaders always respect employee diversity, providing effective communication and interaction to understand their needs and self-determination to ensure fair treatment and distribution in different workplaces. Third, the accessible leadership style provides a fault-tolerant working atmosphere that improves employees energized to strive for their goals. IL narrows the distance between leaders and employees, so that employees do not have to worry about the negative consequences of raising different opinions, seeking feedback, and facing the pressure of failure.1,18 Given the above arguments, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1: Inclusive leadership is positively related to employee’s proactive (work) behavior.

The Mediating Role of Employee Trust

According to COR theory, employees value leaders as a favorable resource to help them to complete their tasks.19 On the one hand, the resources inclusive leaders offer are work-related knowledge and experiences, as well as emotional and relationship resources. Specifically, IL creates good conditions of openness, support, fairness, and tolerance to improve belongingness and psychological safety for diversified subordinates and advances the level of interpersonal care and attention. Such active interaction between leaders and employees and generates higher employee affective trust, which is a highly directional psychological state to further affects a series of perceptions, attitudes, and behavior of employees.20,21 As studies discussed,35–37 once employees raise their trust in direct supervisors and senior management teams, they would demonstrate high levels of organizational citizenship behavior and initiatives. In contrast, if followers feel untrustworthy with the leader’s behavior, they usually reduce their self-efficacy, voice, and initiative to protect themselves with their own interests as the most important principle. Since inclusive leaders treat each subordinate in a respectful and fair manner, employees can immediately seek help and coordination from their leaders when encountering emergencies and interpersonal conflicts. Differing from transformational and empowering leadership, the emotional and relationship resources provided by inclusive leaders often far exceed the psychological expectations of employees in the relationship between the two parties.17 This means that when the subordinates recognize that the leader cares more about themselves, which would close the relationship with the leader, thereby increasing trust in leaders. Therefore, we could infer that when employees feel the leadership’s support, fairness, and abundant work resources, employee trust will increase.

On the other hand, employee trust helps to predict their positive attitude and work behavior in the workplace.36 Proactive people often suffer from certain risks because challenging the status quo, speaking up, mistakes and failure may lead to dissatisfaction and even punishment of the organization, which would weaken their initiative.14 However, the features of IL fault-tolerant and fair treatment that strengthen employees’ psychological security and trust have significantly reduced employees’ concerns about the risks of active behavior. Based on the COR theory, when the organization’s resources are insufficient or limited, employees would invest more in leaders in order to acquire, retain and preserve resources.38 This means that employees will transform their trust in the inclusive leaders into a positive attitude, pay more effort, and actively participate in their work (ie, resource investment) to avoid disappointing leaders (ie, resource loss).22 Consequently, such trust inspires the reason to escalate employees’ work initiative, and lower their fear of extra-role behavior, thereby facilitating proactive behavior. Therefore, this study proposes that employee trust might mediate the relationship between IL and employee proactive work behavior. Given the analysis, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2: Employee trust mediates the relationship between inclusive leadership and employee’s proactive (work) behavior.

The Moderating Role of Procedural Justice Climate

Procedural justice refers to the policies, processes, procedures, decisions, and outcomes of resource allocation are based on the foundational principles of fairness.12 Procedural justice climate emerges and aggregates at the organizational level when employees subjectively percept such consistent fairness.13,39 Research has demonstrated that procedural justice climate which helps to deliver values, expectations, fair procedures of rewards and punishments to shape the individual positive psychological environment and to guide proactive behavior.40,41 Therefore, as previous studies suggested, this research regards procedural justice climate as a contextual factor that can influence the previously hypothesized relationships between IL, proactive behavior, and employees trust. While the characteristics of IL promote employee self-efficacy, which can be performed even without the authorization of the organization, contextual factors may hinder employee motivation, especially if the workplace environment is not conducive to employee initiative. Employees in teams with a low procedural justice climate would tend to protect their personal interests to avoid work-related concerns and consequences.42 Especially when their initiatives underperform or fail, no matter how tolerant and encouraging IL is, organizations often blame individuals rather than looking at systemic causes. In contrast, employees in teams with a high procedural justice climate easily perceive fair, open, and just workplace environment conveyed by the organization, thereby triggering organizational identification and professional commitment.40 This is consistent with the fairness heuristic theory that people will make judgments about the fair information they are exposed to, and then affect their subsequent attitudes and behavior.43 Accordingly, in a high procedural justice climate, IL has given full play to its characteristics of motivating and inspiring proactive behavior of employees since employees believe they would be treated fairly by organizations. In return, employees are more likely to behave more proactively, such as challenging the status quo and making constructive suggestions.13 Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Procedural justice climate moderates the relationship between inclusive leadership and proactive behavior of employees such that this relationship is stronger when the procedural justice climate is high than when it is low.

This research proposes that the relationship between IL and employees trust strengthens significantly in a procedural justice climate. As stated before (see H2), to preserve and maintain the resources of work-related knowledge, experience, and affective from IL, employees would input more trust in IL. However, the inconsistent and biased procedural work environment would make employees concerned that they are not given equal importance and the interpersonal risk of extra-role behavior, which would debilitate employee trust even though they are encouraged and supported by IL.12 Instead, a procedural justice climate provides a fair, transparent, and democratic workplace where employees do not have to worry about the perception of negative consequences of freely expressing voices and new ideas and reduces the risk of uncertainty in human interactions and job feedback. Under procedural justice climate, the role of IL would maximize the influence to increase employee affective dependence and trust, and a stronger sense of belonging to the team in return. When employees who trust the organization and leaders are encouraged by this strong sense of security in fair and mutually beneficial relationships, they would augment their contribution through more active behavior.13 Consequently, under high justice procedural climate, the positive correlation between IL and employee trust will be stronger than in the case of a low justice procedure. Following the inference, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 4: Procedural justice climate moderates the relationship between inclusive leadership and employee trust such that this relationship is stronger when procedural justice climate is high than when it is low.

Given the above theories and hypothesiss, the conceptual model of this research is shown in Figure 1.

|

Figure 1 Conceptual model of this research. |

Research Method

Sample and Data Collection

We collected the data from 40 project teams at 20 companies located in Beijing, Shanghai, Wuhan, and Guangzhou. In order to collect more useable samples, the snowball sampling method suitable for the Chinese context was adopted.44 In total, 400 team members from 40 project teams were invited to participate in our study, while 304 team members (76%) from 40 projected teams (100%) provided useable responses finally. In the sample, the average team size was 8.53 members. Of the team supervisors, 85% were males and approximately 85% had at least attained a bachelor’s degree; their average age was 37.50 years old (SD = 6.03), and their average tenure was 9.48 years (SD = 4.84). Of the team members, 64% were males and 83.5% had at least attained a bachelor’s degree; their average age was 30.95 years old (SD = 7.44), and their average tenure was 4.21 years (SD = 5.07).

To avoid the problems caused by potential common method biases, we collected data from two different sources (ie, team supervisors and team members).45 For team members, they were asked to response the questionnaires of IL, employee trust, procedural justice climate, and their demographic information. For team supervisors, they were asked to rate each team member’s proactive behavior and their demographic information. All respondents completed the questionnaires voluntarily and were assured that their responses would be kept confidential in the survey.

Measures

Inclusive Leadership

A nine-item scale, developed by Carmeli et al, was used to measure IL.28 All nine items were measured on a five-point scale ranging from 1 = “Not at all” to 5 = “A large extent”. Sample items include “The direct supervisor is available for consultation on problems.” and “The direct supervisor encourages me to access him/her on emerging issues.”. The Cronbach’s α for this scale was 0.96.

Employee Trust

A 11-item scale, developed by McAllister, was used to measure employee trust.46 All 11 items were measured on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = “Strongly disagree” to 5 = “Strongly Agree”. Sample items are “I would have to say that we have both made considerable emotional investments in our working relationship.” and “My supervisor approaches his/her job with professionalism and dedication”. The Cronbach’s α for this scale was 0.96.

Procedural Justice Climate

A seven-item scale, developed by Colquitt, was used to measure each team member’s perception of procedural justice.47 Because procedural justice climate is a team level construct, according to Chan’s typology of composition models, we adopted the additive composition approach, which involved averaging across individual team members’ own procedural justice perceptions, regardless of within-team variability in those perceptions.48 All seven items were measured on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = “to a small extent” to 5 = “to a large extent”. A sample item is “To what extent have you been able to express your views and feelings during the procedures used to arrive at your outcome?” Consistent with the level theory and past research that has theorized and tested this construct at the team level,49 we aggregated team members’ perceptions of procedural justice to the team level to form the measure of procedural justice climate. In order to check the viability of procedural justice climate, we computed rwg values and obtained an average rwg of 0.96 (median = 0.94). The rwg values were above the conventionally acceptable rwg value of 0.70.50 In addition, we also calculated the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC1) and reliability of group mean (ICC2).51 The results for ICC1 is 0.91 and ICC2 is 0.98. These results showed the appropriateness of data aggregation. The Cronbach’s α for this scale was 0.97.

Proactive Behaviour

Proactive behavior was measured by using a seven-item scale of Frese et al.52 Each team supervisor was asked to respond to this scale in this study. All seven items were measured on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = “Strongly disagree” to 5 = “Strongly Agree”. A sample items is “Whenever something goes wrong, he/she searches for a solution immediately.” The Cronbach’s α for this scale was 0.91.

Control Variables

Prior research has demonstrated that some individual variables are related to proactive behavior, such as tenure,52 education level,4 age and gender.53 In addition, team size was also controlled for because prior research suggested that size might influence the level of proactive behavior on the part of employees.54

Results

Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Discriminant Validity

We conducted a confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) to compare our hypothesized 4-factor model (ie inclusive leadership, employee trust, procedural justice climate, and proactive behavior) to a series of alternative models (three-factor model, two-factor model, and one-factor model). Table 1 presents the CFA results. As shown, the hypothesized four-factor model [χ2(521) = 953.21, NFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.95, CFI = 0.96, SRMR = 0.04, and RMSEA = 0.05] fits the data best. Therefore, these results supported our measures’ discriminant validity.

|

Table 1 Results of Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table 2 presents the results of correlation analysis. As shown in the table, at the individual level, IL was positively related to both employee trust (r = 0.53, p < 0.001) and proactive behavior (r = 0.34, p < 0.001) and employee trust was positively related to proactive behavior (r = 0.41, p < 0.001). These results provide initial support for some of our hypotheses. In addition, as all demographic variables did not significantly correlate with the outcome variable, these will be excluded as control variables in the following analysis.

|

Table 2 Descriptive Statistics and Intercorrelations |

Hypotheses Testing

We used SPSS 21.0 and HLM 6.02 to conducted hierarchical regression and hierarchical linear models for our hypotheses testing. H1 predicted that IL is positively related to proactive behavior. Findings provide empirical evidence that shows the significant effect of IL on proactive behavior (B = 0.34, p < 0.001, Model 2). Thus, H1 was supported. H2 predicted that employee trust mediates the relationship between IL and proactive behavior. To examine this mediation effect, we followed Hayes procedure.55 The finding can be observed in Table 3. IL was significantly associated with employee trust (B = 0.53, p < 0.001, Model 1) and the mediator was significantly related to proactive behavior (B = 0.32, p < 0.001, Model 3) when the predictor variable was in the model (B = 0.17, p< 0.001, Model 3). This result suggests that IL partially mediated the relationship between IL and proactive behavior. Bootstrapping of the sampling distribution was also conducted regarding the indirect effect. The results showed that the 95% confidence interval of the indirect effect was between 0.07 and 0.23. Thus, H2 was supported.

|

Table 3 Results of Hypotheses Testing |

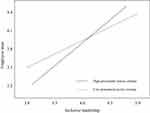

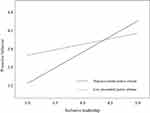

H3 and H4 predicted that procedural justice climate moderates the relationship between IL and proactive behavior and the relationship between IL and employee trust, respectively. These two hypotheses were tested by using HLM. As shown in Table 3, the interaction of IL and procedural justice climate was significant when the dependent variable is proactive behavior (γ = 0.13, p < 0.05) and when the dependent variable is employee trust (γ = 0.14, p < 0.05). In order to reveal the interaction effect more clearly, we followed the procedures proposed by Aiken and West to plot interaction by using a cut value of one standard deviation above and below the mean of procedural justice climate (see Figures 2 and 3).56 As predicted, when procedural justice climate was high, the relationship between IL and proactive behavior and the relationship between IL and employee trust were stronger. These outcomes further supported the moderating effect of procedural justice climate, as depicted in H3 and H4.

|

Figure 2 Moderating effect of procedural justice climate on the relationship between inclusive leadership and employee trust. |

|

Figure 3 Moderating effect of procedural justice climate on the relationship between inclusive leadership and proactive behaviour. |

Discussion

The proactive behavior of employees is one of the key determinants of organizational development in a competitative business environment. While much work has contributed to our knowledge of the antecedents of employees’ proactive behavior, scant attention has been paid to the mechanisms that influence their psychological state and work behavior. The aim of this research is to investigate the relationship between inclusive leadership (IL) and employee proactive behavior, along with mediating role of employee trust and the moderating role of procedural justice climate. Drawing upon COR theory and fairness heuristic theory, this study develops a cross-level moderated mediation model and obtained three findings through leader-member matching data analysis.

First, the results show that IL has a significant positive effect on employee’s proactive work behavior. The openness, accessibility, and availability of leaders not only increase employees’ perceptions of inclusiveness, but also improve self-efficacy.7,33 Besides, IL helps to close the distance with employees and promote effective communication because they appreciate their diversity and are willing to understand their needs.15,26 Furthermore, a fault-tolerant working atmosphere IL provides encourages employees to raise different opinion, and encourage innovation behavior and creativity.34 Such positive interaction would bring together to the final employees’ attitude and active behavior, which is consistent with the prior literature (see Qi et al, 2017; Zeng et al, 2020).18,32

Secondly, the finding sheds light on the mediating role of employee trust in the relationship between IL and employee proactive behavior. It means that IL has a positive impact on employee trust, and employee trust is positively related to employee proactive behavior. The characteristics of IL could provide work-related knowledge and interpersonal care and attention, which creates calm and supportive workplace conditions to improve belongingness and psychological safety for diversified subordinates.20 Our results are in line with existing research, that often inclusive leaders provide emotional and relationship resources that far exceed the psychological expectations of employees in the relationship between the two parties. When employees generate a highly directional psychological state, it increases higher affective trust.21 In return, employees would take the initiative to challenge the status quo and make constructive suggestions by lowering their fear of extra-role behavior to take initiative. The reasonable explanation is that fault tolerance and fair treatment of IL could reduce employee concerns about the risk of proactive behavior. Our results are in line with existing research,35–37 once employees raise their trust in direct supervisors and senior management teams, they would perform high levels of organizational citizenship behavior and initiatives. Therefore, employee trust plays as a mediator to further closely link the relationship between employees, their own cross-professional project team, and the organization.

Finally, the procedural justice climate has a significant moderating impact on the relationship between IL and employees’ active behavior and the relationship between IL and employee trust. The results illustrate that the cross-level effect of procedural justice climate is consistent with the argument of Tangirala and Ramanujam.41 This means that in teams with a strong atmosphere of procedural justice conveyed by the organization, employees make judgments about the fair information they are exposed to, which shapes their individual positive psychological and guides their subsequent proactive attitudes and behaviors.40,41,43 Moreover, a procedural justice climate provides a transparent workplace environment where the role of IL would maximize the influence to increase employee affective dependence and trust in the team. It is because when the just contextual factor provides favorable conditions to make employees feel equal importance and stronger social network relationships, the concerns of interpersonal risk of extra-role behavior would be reduced.12 That is, employees who perceive a strong sense of security from the organization and leadership in a fair and mutually beneficial relationship will increase their contribution through more positive behavior.

Theoretical Implications

The contribution of this work is threefold. First, this research develops a cross-level moderated mediation model to reveal the influence mechanism of IL on employee proactive behavior. The findings demonstrate that the openness, accessibility, and availability of leaders increase employees’ perceptions of inclusiveness and then positively promote the employees’ proactivity, which is consistent with the prior literature (see Qi et al, 2017; Zeng et al, 2020).18,32

Secondly, drawing upon COR theory, this study dedicated to to identify the influence mechanism of IL by examining the role of employee trust in the superior-subordinate relationship. Existing studies mainly focus on the mediating mechanism of work engagement and psychological empowerment,57 overlooking other possible factors. Moreover, some commonalities have been identified with the theoretical model of IL,17 this research, however, further conceptualizes the perceptions of followers on workgroup identification and psychological empowerment to provide a more abundant, dynamic picture. Although the preconditions and model framework of this research are similar to the IL approach, it is not superficial to add and test some variables to their framework, but rather an essential practical expression. Specifically, based on COR theory, we highlight the mutual interaction between leaders and employees and the influence of the establishment of trust relationships on employee behavior, which has never been done before.

Finally, drawing upon fairness heuristic theory, this paper contributes to determining the necessary condition of procedural justice climate on individual initiative and contextual factors, extending our understanding of the boundary conditions of proactive behavior. Prior research mainly emphasizes the individual-level antecedents of employee proactive behavior (ie, personality, motivation, self-efficacy) which neglects the contextual factors.17 Our findings not only fill the research gap, but also explain why individuals without proactive personality traits may still have initiative and proactive behavior in the workplace.

Practical Implications

This study has several practical implications. Firstly, from the leadership aspect, leaders should cultivate inclusiveness to provide emotional support and work resources for subordinates to increase employee trust. IL can enhance the team members’ perception of belonging and group identity, reduce resources competition within the team, and help team members to cope with work challenges and performance pressures. Moreover, IL not only navigates employees with proactive traits but also inspires non-active personality subordinates to take the initiative to change and improve work performance. This is because those employees of any personality type can feel the support and encouragement of IL, thereby enhancing their trust in leaders and organizations, and are more willing to work commitment. Finally, it points to that from the perspective of organizational development, it is important to urge an inclusive atmosphere and measures of procedural justice. To achieve performance efficiently, only goal-oriented leadership is not sufficient, especially, team-oriented organizational structures are often temporary cross-professional teams formed for short-term goals. In such a situation, it is difficult to lead subordinates to complete the job tasks and achieve the goals. Therefore, organizations should create a just workplace environment to improve team trust, cooperate with each other, and share successful experiences and knowledge, which would more effectively and efficiently benefit the organizational performance.

Limitation and Future Research

This study has some limitations. First, although this study supports all hypotheses proposed by the rational theory perspective, our research design uses cross-sectional data, which limits conclusions about causality. Second, given the time and resource constraints, the findings are only from some parts of China, so future research may expand data collection sources to improve generalizability. Third, since the empirical findings show partial mediation effects between IL and proactive behavior, such results imply the existence of other possible variables. Future research may consider different mediation variables from different theoretical viewpoints for discussion. Finally, although we revealed the role of procedural justice climate as the most crucial contextual factor to respectively strengthen the relationship among inclusive leadership, proactive behavior, and employee trust, future research may include Randel et al the top management’s commitment to inclusion as another cross-level moderator in their research models.17

Conclusion

Theoretically, drawing upon COR theory and fairness heuristic theory, this research develops a cross-level moderated mediation model to explain how employees perceive leaders’ inclusiveness to generate proactive behavior. All our hypotheses are supported. Specifically, the results highlight that the characteristics (ie, openness, accessibility, availability, support, and fault-tolerance) of IL significantly improve employees’ enthusiasm for proactive work behavior. Besides, employee trust plays a mediating role within the relationship. Meanwhile, the procedural justice climate moderates the relationship between IL and proactive behavior, and the relationship between IL and employee trust, respectively. Practically, IL not only provides emotional support to increase employee trust but also inspires subordinates with a non-active personality to take initiative. Team-oriented organizational structures should promote procedural justice measures to create a trusting and fair work environment that more effectively furthers the effectiveness of IL on positive work behaviors of employees.

Ethics Statement

All procedures of this research were conducted in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Before conducting this study, the proposals and ethical standards were reviewed and approved by the academic committee of Macau University of Science and Technology. Moreover, we formally introduced to all participants important information about this study and obtained their consent before they participated in the research. Finally, all participant information is anonymous and confidential.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the article editor and anonymous reviewers for their valuable and thoughtful comments and suggestions.

Funding

This research has been supported by the Faculty Research Grant of Macau University of Science and Technology (grant no. FRG-22-049-MSB).

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in relation to this work.

References

1. Hirak R, Peng AC, Carmeli A, Schaubroeck JM. Linking leader inclusiveness to work unit performance: the importance of psychological safety and learning from failures. Leadersh Q. 2012;23(1):107–117. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.11.009

2. Crant JM. Proactive behavior in organizations. J Manage. 2000;26(3):435–462. doi:10.1177/014920630002600304

3. Parker SK, Bindl UK, Strauss K. Making things happen: a model of proactive motivation. J Manage. 2010;36(4):827–856. doi:10.1177/0149206310363732

4. Parker SK, Collins CG. Taking stock: integrating and differentiating multiple proactive behavior. J Manage. 2010;36(3):633–662. doi:10.1177/0149206308321554

5. Greguras GJ, Diefendorff JM. Why does proactive personality predict employee life satisfaction and work behavior? A field investigation of the mediating role of the self‐concordance model. Pers Psychol. 2010;63(3):539–560. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01180.x

6. Anseel F, Beatty AS, Shen W, Lievens F, Sackett PR. How are we doing after 30 years? A meta-analytic review of the antecedents and outcomes of feedback-seeking behavior. J Manage. 2015;41(1):318–348. doi:10.1177/0149206313484521

7. Raub S, Liao H. Doing the right thing without being told: joint effects of initiative climate and general self-efficacy on employee proactive customer service performance. J Appl Psychol. 2012;97(3):651. doi:10.1037/a0026736

8. Frese M, Fay D, Hilburger T, Leng K, Tag A. The concept of personal initiative: operationalization, reliability and validity in two German samples. J Occup Organ Psychol. 1997;70(2):139–161. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8325.1997.tb00639.x

9. Porath C, Spreitzer G, Gibson C, Garnett FG. Thriving at work: toward its measurement, construct validation, and theoretical refinement. J Organ Behav. 2012;33(2):250–275. doi:10.1002/job.756

10. Baer MD, Matta FK, Kim JK, Welsh DT, Garud N. It’s not you, it’s them: social influences on trust propensity and trust dynamics. Pers Psychol. 2018;71(3):423–455. doi:10.1111/peps.12265

11. Lai F-Y, Lin -C-C, Lu S-C, Chen H-L. The role of team–member exchange in proactive personality and employees’ proactive behavior: the moderating effect of transformational leadership. J Leadersh Organ Stud. 2021;28(4):429–443. doi:10.1177/15480518211034847

12. Cropanzano R, Li A, Benson L. Peer justice and teamwork process. Group Organ Manage. 2011;36(5):567–596. doi:10.1177/1059601111414561

13. Sung SY, Choi JN, Kang S-C. Incentive pay and firm performance: moderating roles of procedural justice climate and environmental turbulence. Hum Resour Manage. 2017;56(2):287–305. doi:10.1002/hrm.21765

14. Parker SK, Wang Y, Liao J. When is proactivity wise? A review of factors that influence the individual outcomes of proactive behavior. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2019;6(1):221–248. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012218-015302

15. Den Hartog DN, Belschak FD. When does transformational leadership enhance employee proactive behavior? The role of autonomy and role breadth self-efficacy. J Appl Psychol. 2012;97(1):194–202. doi:10.1037/a0024903

16. Shore LM, Randel AE, Chung BG, Dean MA, Holcombe Ehrhart K, Singh G. Inclusion and diversity in work groups: a review and model for future research. J Manage. 2011;37(4):1262–1289. doi:10.1177/0149206310385943

17. Randel AE, Galvin BM, Shore LM, et al. Inclusive leadership: realizing positive outcomes through belongingness and being valued for uniqueness. Hum Resour Manage Rev. 2018;28(2):190–203. doi:10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.07.002

18. Qi L, Liu B. Effects of inclusive leadership on employee voice behavior and team performance: the mediating role of caring ethical climate. Front Commu. 2017;2:8. doi:10.3389/fcomm.2017.00008

19. Halbesleben JR, Wheeler AR. To invest or not? The role of coworker support and trust in daily reciprocal gain spirals of helping behavior. J Manage. 2015;41(6):1628–1650. doi:10.1177/0149206312455246

20. Tzafrir SS, Baruch Y, Dolan SL. The consequences of emerging HRM practices for employees’ trust in their managers. Pers Rev. 2004;33(6):628–647. doi:10.1108/00483480410561529

21. Tett RP, Guterman HA. Situation trait relevance, trait expression, and cross-situational consistency: testing a principle of trait activation. J Res Pers. 2000;34(4):397–423. doi:10.1006/jrpe.2000.2292

22. Avolio BJ, Gardner WL, Walumbwa FO, Luthans F, May DR. Unlocking the mask: a look at the process by which authentic leaders impact follower attitudes and behavior. Leaders Q. 2004;15(6):801–823. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2004.09.003

23. Fuller JB, Marler LE. Change driven by nature: a meta-analytic review of the proactive personality literature. J Vocat Behav. 2009;75(3):329–345. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2009.05.008

24. Fritz C, Sonnentag S. Antecedents of day-level proactive behavior: a look at job stressors and positive affect during the workday. J Manage. 2009;35(1):94–111. doi:10.1177/0149206307308911

25. Belschak FD, Den Hartog DN. Pro‐self, prosocial, and pro‐organizational foci of proactive behavior: differential antecedents and consequences. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2010;83(2):475–498. doi:10.1348/096317909X439208

26. Nishii LH, Mayer DM. Do inclusive leaders help to reduce turnover in diverse groups? The moderating role of leader-member exchange in the diversity to turnover relationship. J Appl Psychol. 2009;94(6):1412–1426. doi:10.1037/a0017190

27. Nembhard IM, Edmondson AC. Making it safe: the effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. J Organ Behav. 2006;27(7):941–966. doi:10.1002/job.413

28. Carmeli A, Reiter-Palmon R, Ziv E. Inclusive leadership and employee involvement in creative tasks in the workplace: the mediating role of psychological safety. Creativ Res J. 2010;22(3):250–260. doi:10.1080/10400419.2010.504654

29. Avery DR, McKay PF, Wilson DC, Volpone S. Attenuating the effect of seniority on intent to remain: the role of perceived inclusiveness. In:

30. Fang Y-C, Chen J-Y, Wang M-J, Chen C-Y. The impact of inclusive leadership on employees’ innovative behavior: the mediation of psychological capital. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1803. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01803

31. Wang Q, Wang J, Zhou X, Li F, Wang M. How inclusive leadership enhances follower taking charge: the mediating role of affective commitment and the moderating role of traditionality. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2020;13:1103. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S280911

32. Zeng H, Zhao L, Zhao Y. Inclusive leadership and taking-charge behavior: roles of psychological safety and thriving at work. Front Psychol. 2020;11:62. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00062

33. He B, He Q, Sarfraz M. Inclusive leadership and subordinates’ pro-social rule breaking in the workplace: mediating role of self-efficacy and moderating role of employee relations climate. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2021;14:1691. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S333593

34. Chen XP, Eberly MB, Chiang TJ, Farh JL, Cheng BS. Affective trust in Chinese leaders: linking paternalistic leadership to employee performance. J Manage. 2014;40(3):796–819. doi:10.1177/0149206311410604

35. Siyal S, Xin C, Umrani WA, Fatima S, Pal D. How do leaders influence innovation and creativity in employees? The mediating role of intrinsic motivation. Admin Soc. 2021;53(9):1337–1361. doi:10.1177/0095399721997427

36. Mayer RC, Gavin MB. Trust in management and performance: who minds the shop while the employees watch the boss. Acad Manage J. 2005;48(5):874–888. doi:10.5465/AMJ.2005.18803928

37. Ye S, Xiao Y, Wu S, Wu L. Feeling trusted or feeling used? The relationship between perceived leader trust, reciprocation wariness, and proactive behavior. Psychol Res Behav Manage. 2021;14:1461. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S328458

38. Hobfoll SE, Halbesleben J, Neveu JP, Westman M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: the reality of resources and their consequences. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2018;5(1):103–128. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640

39. He H, Zhu W, Zheng X. Procedural justice and employee engagement: roles of organizational identification and moral identity centrality. J Bus Ethics. 2014;122(4):681–695. doi:10.1007/s10551-013-1774-3

40. Naumann SE, Bennett N. A case for procedural justice climate: development and test of a multilevel model. Acad Manage J. 2000;43(5):881–889. doi:10.2307/1556416

41. Walumbwa FO, Hartnell CA, Oke A. Servant leadership, procedural justice climate, service climate, employee attitudes, and organizational citizenship behavior: a cross-level investigation. J Appl Psychol. 2010;95(3):517. doi:10.1037/a0018867

42. Tangirala S, Ramanujam R. Employee silence on critical work issues: the cross level effects of procedural justice climate. Pers Psychol. 2008;61(1):37–68. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2008.00105.x

43. Lind EA. Fairness heuristic theory: justice judgments as pivotal cognitions in organizational relations. In: Greenberg J, Cropanzano R, editors. Advances in Organizational Justice. Vol. 2001. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 2001:56–88.

44. Sun L-Y, Aryee S, Law KS. High-performance human resource practices, citizenship behavior, and organizational performance: a relational perspective. Acad Manage J. 2007;50(3):558–577. doi:10.5465/amj.2007.25525821

45. Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

46. McAllister DJ. Affect- and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Acad Manage J. 1995;38(1):24–59. doi:10.2307/256727

47. Colquitt JA. On the dimensionality of organizational justice: a construct validation of a measure. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86(3):386–400. doi:10.1037//0021-9010.86.3.386

48. Chan D. Functional relations among constructs in the same content domain at different levels of analysis: a typology of composition models. J Appl Psychol. 1998;83(2):234–246. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.83.2.234

49. Colquitt JA, Noe RA, Jackson CL. Justice in teams: antecedents and consequences of procedural justice climate. Pers Psychol. 2002;55(1):83–109. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2002.tb00104.x

50. James LR, Demaree RG, Wolf G. Rwg: an assessment of within-group interrater agreement. J Appl Psychol. 1993;78(2):306–309. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.78.2.306

51. Bliese PD. Within-group agreement, non-Independence, and reliability: implications for data for data aggregation and analysis. In: Klein KJ, Kozlowski SWJ, editors. Multilevel Theory, Research, and Methods in Organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2000:349–381.

52. Frese M, Fay D. Personal initiative (PI): an active performance concept for work in the 21st century. Res Organ Behav. 2001;23:133–187.

53. Bohlmann C, Zacher H. Making things happen (un) expectedly: interactive effects of age, gender, and motives on evaluations of proactive behavior. J Bus Psychol. 2021;36:609–631. doi:10.1007/s10869-020-09691-7

54. Kuo -C-C, Ye Y-C, Chen M-Y, Chen LH. Psychological flexibility at work and employees’ proactive work behavior: cross‐level moderating role of leader need for structure. Appl Psychol. 2018;67(3):454–472. doi:10.1111/apps.12111

55. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2013.

56. Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991.

57. Schmitt A, Den Hartog DN, Belschak FD. Transformational leadership and proactive work behavior: a moderated mediation model including work engagement and job strain. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2016;89(3):588–610. doi:10.1111/joop.12143

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.