Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

Impact of Co-Worker Ostracism on Organizational Citizenship Behavior Through Employee Self-Identity: The Moderating Role of Ethical Leadership

Received 14 April 2023

Accepted for publication 25 July 2023

Published 18 August 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 3279—3302

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S415036

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 5

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Lianying Zhang, Ziqing Liu, Xiaocan Li

College of Management and Economics, Tianjin University, Tianjin, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Ziqing Liu, College of Management and Economics, Tianjin University, 92 Weijin Road, Nankai District, Tianjin, 300072, People’s Republic of China, Tel +86 16622808037, Email [email protected]

Purpose: Positive interpersonal interactions are indispensable for employees to engage in organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) that benefits teamwork; however, co-worker ostracism triggers interpersonal isolation, inhibiting OCB. This research aims to leverage the intervention of ethical leadership in the ostracism–OCB relationship to moderate the harmful ostracism and promote ostracized employees’ OCB through employee self-identity.

Methods: This research chose 122 MBA to participate in Study 1’s scenario experiment to verify the causality between variables. Study 2 used 295 valid questionnaires from full-time employees to generalize the experimental results to field settings and compensate for external validity. Two studies used Hayes’s conditional process model to test the conditional direct and indirect relationships.

Findings: This research revealed that high levels of ethical leadership effectively transitioned the harmful ostracism and promoted ostracized employees’ OCB by satisfying ostracized employees’ needs for identity recognition. Accordingly, the direct and indirect effects of co-worker ostracism on OCB through employee self-identity would be positive at high levels of ethical leadership, but negative at low levels.

Originality: This research first introduces an identity perspective on ethical leadership in moderating the ostracism–OCB relationship. Based on the social identity theory of leadership, this research fills the gap in ostracism and OCB research calling for leadership interventions. It extends a novel insight into inspiring ostracized employees’ participation in OCB through employee self-identity.

Practical Implications: This research provides the managerial applications of ethical leadership for China organizations to reduce inadvertent inactions, accept employees’ identities, and value interpersonal communication for effectively transitioning harmful ostracism.

Keywords: ethical leadership, co-worker ostracism, organizational citizenship behavior, individual identity, relational identity, collective identity

Introduction

The more frequent teamwork in the work setting requires employees to engage in extra-role efforts to improve organizational effectiveness.1,2 These extra-role efforts are known as organizational citizenship behavior (OCB), referring to

individual behavior that is discretionary, not directly or explicitly recognized by the formal reward system, and that in the aggregate promotes the effective functioning of the organization.3

In a workplace full of positive interpersonal interactions, employees are willing to participate in more OCB to offer enormous benefits to teamwork based on a sense of altruism, voice, and conscientiousness.4–6 However, as teamwork has increased dramatically, the need for close interpersonal interactions and frequent communication with co-workers enables employees to be susceptible to co-worker ostracism, leading to a sense of isolation of being outside the team and hindering ostracized employees from participating in extra-role efforts to boost organizational advantages.7,8

Co-worker ostracism is “when an individual or group omits to take actions that engage another organizational member when it is socially appropriate to do so”.9 Co-worker ostracism reflects low-intensity social disregard and unclear intentions of malicious harm, such as avoiding eye contact and ignoring co-workers’ greetings.10,11 With the in-depth study of the omission nature of co-worker ostracism in socially engaging behaviors,12 researchers find its “bright side” that ostracized employees conduct prosocial behaviors, such as OCB, to realize positive impression management for the account of regaining co-workers’ attention and acceptance.13–15 But undeniably, the unclear intentions of co-worker ostracism cause ostracized employees to make “sinister attributions” for no malicious inactions once ostracized employees fall into one-side misunderstanding,9 reducing ostracized employees’ efforts in extra-role social connection.16,17 Hence, it is intriguing to identify under what conditions these contradictory findings occur. Especially for effectively avoiding the potential harm of co-worker ostracism to OCB in teamwork, this research follows the call of scholars to further explore what specific condition transitions the harmful ostracism and spurs ostracized employees to engage in pro-social behaviors (eg, OCB) to benefit organizational effectiveness.12

Previous studies attempted to leverage ostracized employees’ own ability and personality, such as alternative job mobility18 and approach temperament,19 to transition the inhibitory effect of co-worker ostracism on OCB and support the tendency in pro-social reconnection behaviors. Nevertheless, these studies found that leveraging ostracized employees’ own influence on belongingness and in-group identity merely weakened the negative behavioral tendency to less OCB. The inability to transition the behavioral tendency to positive extra-role efforts is because these studies ignore that employees need the support of organizational interventions to truly satisfy their sense of belonging that they need to conduct pro-social citizenship behaviors.20 For organizational interventions in strengthening employees’ belongingness, extant research has found that satisfaction with the support of supervisory communication, compared with co-worker communication, enables employees to perceive being embedded in the organization and engage in OCB.21 This supervisory communication arises from effective leadership behaviors of organizational representatives in the moral component, especially ethical leadership, because ethical leaders as moral group prototypicality show honest two-way communication with employees and value recognition to accept employees as insiders.22,23 Ethical leadership is defined as

the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to employees through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision making.24

Although the positive role of ethical leadership in alleviating interpersonal tensions between ostracized employees and co-workers has attracted attention from scholars,25 there is still a lack of sufficient empirical evidence to support the effectiveness of leveraging ethical leadership to transition the harmful ostracism and inspire ostracized employees’ participations in more OCB. Based on the advances in ethical leadership research and unsolved research gaps, this research aims to explore the moderating role of ethical leadership in transitioning the harm of co-worker ostracism to OCB and enhancing ostracized employees’ willingness to OCB.

According to the social identity theory of leadership, the representative of group identity (ie, ethical leadership)23 demonstrates their own prototypicality and focuses on the fairness of interpersonal interaction to shape employees’ identity and appropriate behaviors.26–28 In this sense, ethical leadership provides powerful support for expected interpersonal interaction and determines their identities as insiders of the organization. Consistent with the previous research on the social identity model of organizational leadership,29 leaders, as group prototypicality, speak more authoritatively to employees’ identities.23 Based on this reasoning, when employees face co-worker ostracism to feel outside of the organization, ethical leadership relies on the moral identity of group prototypicality to recognize their identities within the organization to weaken excluded encounters. Meanwhile, ethical leadership implies the moral essence to positively influence employees who perceive being an organizational membership to engage in OCB for the effectiveness of organizational functioning.30 Therefore, relying on the social identity theory of leadership, this research introduces the identity perspective on ethical leadership to clarify how ethical leadership transitions the harmful co-worker ostracism and inspires ostracized employees’ OCB.

Based on the social identity theory of leadership,28 ethical leadership provides employees with value recognition and honest communication to positively recognize employee identity within the organization. Ethical leadership helps employees reduce the sense of isolation following co-worker ostracism and fosters ostracized employees’ willingness to make extra-role efforts for the organization. Employee identity refers to how they define their self-conception relative to organizational members (identify oneself as unique from co-workers vs a partner in a dyadic relationship vs a member in an organization).31 Once ostracized by co-workers, employees perceive interpersonal isolation and lack of belongingness, reducing their self-identity regarding interpersonal connections with organizational members.32,33 Employee self-identity is diminished, which reduces their citizenship behaviors toward the organizational interests.34 Extant research on this mediating role of employee self-identity only concentrated on one level of self-identity (eg, the collective level of self-identity) in ostracism–OCB relations.35,36 To our knowledge, a few studies combined all three levels: individual identity, relational identity, and collective identity. However, because of the coexistence of the three levels of self-identity in social interactions,31,37,38 strongly adhering to one or both levels ignores their interconnection. Moreover, it is challenging to play the complementary role of identities in creating a sense of meaning and belonging within the organization.38,39 Meanwhile, it has been found that three levels of employee self-identity are especially relevant when considering the support of leader group prototypicality (eg, ethical leadership) in interpersonal interactions.40 In short, this research anticipates that employees with the support of ethical leadership reinforce three levels of employee self-identity through effective organizational communications and leader recognition and are willing to exhibit extra-role efforts following experiences of co-worker ostracism.

Overall, this research explores the moderating role of ethical leadership in transitioning the inhibitory effect of co-worker ostracism on OCB and promoting ostracized employees’ willingness to engage in OCB through the mediating role of three levels of employee self-identity (see Figure 1). This research provides novel insights contributing to previous research on the ostracism–OCB relationship. The main novelty is that this research identifies ethical leadership as the adequate boundary condition in transitioning the harmful co-worker ostracism and inspiring ostracized employees’ willingness to engage in OCB from an identity perspective, compared with previous research on the powerlessness of leveraging employees’ own influence to foster ostracized employees’ tendency to extra-role efforts. This research responds to the call for critical leadership-centric role-playing in dominating employees’ behavioral response to co-worker ostracism.41 In doing so, this research introduces the social identity theory of leadership into the ostracism–OCB relationship. It theorizes that ethical leadership leverages its leader identity of group prototypicality to provide employees with expected interpersonal fairness and alternative organizational communications, enabling employees to identify themselves as insiders and be willing to engage in OCB following experiences of co-worker ostracism. Grounded in this theorizing, this research enriches the related research on the powerful support of ethical leadership in realizing ostracized employees’ behavioral transition.25 Second, based on the support of ethical leadership in the identifying process of employees’ identities, this research further investigates the simultaneous accessibility of three levels of self-identity to mediate the ostracism–OCB relations, extending previous research focusing on one or both levels of employee self-identity.35 It provides a deeper understanding of the ostracism–OCB relations from a complete identity perspective. This research advances the cognitive process of employee self-identity under the support of leader group prototypicality to reveal the moderated mediation effects of ethical leadership on the ostracism–OCB relationship.

|

Figure 1 Conceptual model of our research. |

Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

Co-Worker Ostracism and OCB: The Moderating Role of Ethical Leadership

Co-worker ostracism is viewed as being socially appropriate, less likely to be prohibited, and causes damage to interpersonal interactions.42,43 As Robinson et al9 stated, co-worker ostracism is “the omission of positive attention from others rather than the commission of negative attention”. Employees are susceptible to cues of co-worker ostracism and tend to misinterpret co-workers’ overlook of social niceties as ostracizing behaviors even when there is related information to provide more benign explanations.44 Syrjämäki et al45 argued that employees sensitively recognized the averted gaze by co-workers as a signal of disrupted interpersonal interactions, feeling of being treated in silence and excluded by co-workers. Furthermore, Zhang et al46 empirically demonstrated that employees with disrupted interpersonal interactions disengaged themselves from connections with co-workers outside of work requirements and reduced their tendency to extra-role citizenship behaviors. The reason is that employees’ OCB—voluntary and altruistic activities outside employees’ work requirements—is based on positive interpersonal interactions with the organization.1 To satisfy interpersonal needs, extant research found that ethical leadership provided employees with the powerful support of positive organizational communications and fair value recognition in effectively coping with disrupted interpersonal interactions caused by co-workers.30,47 Additionally, Scott et al13 argue that employees rely on positive interpersonal connections and organizational recognition supported by leader treatment to deal with isolated barriers in interpersonal interactions with co-workers and gain the opportunity to reconnections with the organization to trigger their tendency to pro-social citizenship behaviors. Therefore, this research reasonably speculates that ethical leadership fosters ostracized employees to engage in OCB following experiences of co-worker ostracism.

Ethical leadership recognizes employees’ values and contributions by treating them fairly and respectfully regarding the moral person components.48,49 Ethical leadership enables employees to perceive meaningful value and recognition from organizational representatives.50 Accordingly, under the organizational support of acceptance and recognition provided by ethical leadership, employees decrease a sense of meaningless existence and reidentify value contributions to their organization after being ostracized by co-workers. Employees with embeddable meaning in the organization are willing to act with organizational interests in mind and contribute to more OCB.51

Besides, ethical leadership enables employees to perceive positive interpersonal connections within the organization from two-way communications and provides ethical guidance on altruism in terms of its moral manager component.52,53 Previous research proposed that relative to the co-worker communication satisfaction, satisfaction with the supervisor communication enabled employees to gain a closer interpersonal connection with the organization and perceive the meaningfulness of work efforts, triggering employees’ willingness to engage in extra-role contributions to the organization.21 Hence, when employees feel isolated from the interpersonal interactions within the organization following experiences of co-worker ostracism,54,55 ethical leadership provides them with positive communication and enables ostracized employees to gain interpersonal need fulfillment. These need fulfillment perceptions motivate employees to preserve positive ties by positively engaging in OCB.56 Except for satisfying employees’ needs for positive interpersonal interactions, ethical leadership influences employees to put themselves in the shoes of understanding and tolerating different perceptions and resolving unnecessary conflict situations in the workplace.57 Specifically, under the ethical guidance of ethical leadership, employees avoid sinister attribution bias to create social misperception about co-worker ostracism which merely shows inadvertent actions in the context of misreading social niceties. They eliminate the discomfort from co-workers’ inactions to socially engaging others and are willing to engage in voluntary and altruistic beneficial behavior toward organizational interests. Under the support of positive connections and moral guidance from ethical leadership, employees decrease their propensity to maintain distance from co-workers following co-worker ostracism and gain the interpersonal foundation for social reconnection to promote OCB.

Ostracized employees perceive value recognition and alternative interpersonal interactions from the organizational acceptance of ethical leadership to satisfy their sense of belonging. Extant studies have demonstrated that ostracized employees with the satisfaction of the fundamental human need for belongingness positively engage in OCB to benefit organizational effectiveness.58,59 Hence, under the support of ethical leadership, ostracized employees gain a sense of meaningful existence within the organization and are willing to exhibit beneficially extra-role behaviors towards organizations. In contrast, without the powerful support of ethical leadership, ostracized employees are challenged to eliminate hostility to co-workers’ inaction. They are biased towards the negative perception that co-worker ostracism is a denial of their valuable contributions and are unwilling to make an extra-role effort in the organization. We propose the following:

Hypothesis 1: The relationship between co-worker ostracism and OCB is positive among employees perceiving high levels of ethical leadership and negative among those perceiving low levels of ethical leadership.

Co-Worker Ostracism and Employee Self-Identity: The Moderating Role of Ethical Leadership

Employee self-identity refers to how they define themselves regarding individual characteristics, role relationships, and group memberships, corresponding to individual, relational, and collective identities.30,60 Three levels of employee self-identity rely on positive self-comparisons and interpersonal relationships with organizational members.38 Once employees perceive the differences and the sense of interpersonal isolation caused by co-worker ostracism, they find it challenging to identify their self-identity related to the value and emotional significance of in-group membership.61 To effectively define employee self-identity by attaching to identity-relevant signals in positive interactions within the organization, employees perceive sufficiently identity-relevant cues for good employee-organization relationships from the organization’s representative, the ethical leader.62–64 Meanwhile, precious research introduced the social identity theory of leadership to propose that prototypical leaders (eg, the ethical leader)30 exhibited appropriate leadership behaviors to realize identity implications by shaping employees’ identities within the organization and defining with whom employees identify.27 For example, Costa, Daher, Neves, Velez30 proposed that ethical leadership leveraged identity-relevant information to shape employees’ identities attached to leader group prototypicality, which represents the organization. Accordingly, based on the social identity theory of leadership,28 ethical leadership compensates for employees’ need for belongingness and value recognition undermined by co-worker ostracism. It promotes ostracized employees to positively identify their identities within the organization through positive interpersonal interactions supported by ethical leadership.

This research proposes the moderating role of ethical leadership in the relationship of co-worker ostracism with employee self-identity for several reasons. One reason is that ethical leadership provides ostracized employees with alternative belongingness to promote their self-identity within the organization. Ethical leadership performs positive two-way communication with employees in decision-making.65 Previous studies extended the social identity model of leadership and viewed ethical leadership as leader group prototypicality to convey identity-relevant information such as fair treatment and positive interpersonal interactions for employees, which facilitates employees’ belonging to the organization.23,30 Based on the social identity theory of leadership, this research infers that ethical leadership enables ostracized employees to positively interact with leader group prototypicality which represents the organization’s attitude and support. Indeed, Choi59 provided the testament that ostracized employees rode themselves of the powerlessness to deal with being isolated by co-workers when they perceived powerful organizational support and acceptance to satisfy the feeling of belonging. Following these theoretical propositions and empirical research, when employees experience co-worker ostracism and have difficulty forming a collective identity as organizational members,47 they can regain the satisfaction of alternative organizational connection and inclusion from the acceptance of ethical leadership. Due to the powerful support of ethical leadership in identity-relevant inferences about alternative connections with the organization, ostracized employees are willing to identify their self-concept regarding organizational connections and enhance their collective identity as organizational members.

Likewise, ostracized employees recognize co-worker ostracism as an interpersonal stressor damaging their interpersonal interactions and belongingness to dyadic partners.64 They cannot satisfy the need for personalized belongingness under the endangered dyadic interactions with co-workers. They find it challenging to realize relational identity regarding a role relationship in the organization.66,67 For satisfying employees’ relational role expectations, related research proposed that ethical leadership, as representatives of similar fair and honest organizations, led to employees’ feelings of more excellent dyadic interactions within the organization from an identity lens.49,68,69 For example, Zhu et al49 argued that ethical leadership, as group prototypicality, treated employees fairly and with respect, which encouraged employees to identify with the focal member (eg, ethical leader) and satisfied their needs for role-based belonging and affiliation. As highlighted by the social identity theory of leadership,28 leader group prototypicality helps employees define whom they identify with and provides close dyadic ties.39,70 Consequently, consistent with the identity-relevant implications of ethical leadership,23,30 this research theoretically states that ethical leadership provides ostracized employees with the alternative needs for relational expectations with the ethical leader. The satisfaction of these needs fulfilled by ethical leadership increases employees’ belongingness and connection with a given role relationship to realize their relational identity.

Except for the satisfaction of alternative belongingness, another reason is that ethical leadership emphasizes approving individual values and opinions, thereby repairing ostracism damage to employees’ individual identity. Because unique value and superiority are essential for employees with high individual identity,33,38 employees especially focus on acknowledgment and recognition by others. They are extremely susceptible to the inability to achieve socially recognized success.66 Under conditions of feeling ostracized and neglected by co-workers, employees are less likely to realize recognition from others and praise for their superior talent,9,71 attenuating their motivation to pursue individual identity.72 Except for the co-worker recognition in the same horizontal hierarchy, once employees perceive the recognition at a higher vertical level from the leader who is more authoritative and prototypical as the organization’s representative, they identify the salient signals emphasizing their value uniqueness and meaningfulness in the workplace.73 Furthermore, based on the social identity theory of leadership, extant research demonstrated that ethical leadership conveyed identity-relevant cues as leader group prototypicality provided fair treatment and respect for employees’ opinion and value, shaping employees’ identities within the organization.27,64 Therefore, ethical leadership helps ostracized employees weaken the sense of value denial by providing a high level of value recognition from leader group prototypicality to compensate them. Specifically, ethical leadership positively recognizes ostracized employees’ value and meaningful existence to promote self-enhancement in their work and the realization of individual identity.

Based on the satisfaction of belongingness and value uniqueness, ostracized employees positively identify their three levels of self-identity within the organization with the support of high ethical leadership. In contrast, when ethical leadership is low, ostracized employees cannot gain alternative belongingness and self-worth recognition to satisfy their fundamental needs for effectively defining their identities in the organization. Specifically, without the powerful support of ethical leadership, it is challenging for ostracized employees to eliminate the lack of a sense of meaningfulness and belongingness within the organization caused by co-worker ostracism and gain the opportunity to realize their self-identity. We propose the following:

Hypothesis 2: The relationship between co-worker ostracism and three levels of employee self-identity is positive among employees perceiving high levels of ethical leadership and negative among those perceiving low levels of ethical leadership.

Employee Self-Identity and OCB

The different identities of employees (individual identity, relational identity, and collective identity)37 reflect

that part of an individual’s self-concept which derives from his knowledge of his membership of a social group together with the value and emotional significance attached to that membership.74

Scholars have verified that with the satisfaction of self-concept in developing a meaningful connection with the organization, employees are willing to establish positive social interactions with the organizational membership and engage in citizenship behaviors.75,76 For example, Marstand et al77 found that employees with high self-identity positively defined their self-concept relative to organizational members and were willing to take extra-role behaviors to promote organizational effectiveness. Following the multidimensional conceptualization of employee self-identity,31,63 extant studies found that individual identity,78 relational identity,79 or collective identity80 was positively associated with increased extra-role behaviors, respectively. Although these findings have emphasized that one or both levels of employee self-identity are related to OCB, few have explored the simultaneity of three levels of employee self-identity in affecting OCB. However, employees simultaneously hold three levels of self-identity in socially interacting with organizational members that they self-categorize themselves to prompt pro-group behaviors.37 In this sense, when three levels of self-identity are particularly salient, employees have the positive identity tendency to connect with the organizational members and engage in pro-social connections related to more OCB. In contrast, employees with low self-identity are difficult to assimilate their self-concept into the organization and no longer feel a sense of oneness within the organization to view the organization’s benefits as their own.55 Without identity association and shared interests, they do not engage in extra-role beneficial behaviors. We propose the following:

Hypothesis 3: Three levels of employee self-identity are positively related to OCB.

The Moderating Role of Ethical Leadership in the Indirect Relationship Between Co-Worker Ostracism and OCB

Co-worker ostracism deprives employees of interpersonal interactions and value recognition within the organization.67,81 When employees feel a part of an out-group and dissimilarity from the organization, they cannot define their self-identity with the value and emotional significance attached to their organization.33,37 Employees need to be recognized, appreciated, and included to impart a sense of respect and belongingness for effectively identifying their identities within the organization.31,66 The sense of respect and belongingness declines as the interpersonal interaction relationship is exacerbated by co-worker ostracism,82 thus, undermining employee self-identity. For employees without the positive definition of employee self-identity attached to intimate interactions with the organization, extant research argued that these employees were unable to develop a meaningful connection with the organization and lacked the motivation to make extra-role efforts to benefit the organizational effectiveness.77,83 Therefore, employee self-identity serves as a mediator, being affected by co-workers’ ostracizing behaviors and then, in turn, decreasing ostracized employees’ OCB.

In terms of the vital identity connections in interpersonal interactions, previous research argues that ethical leader provides favorable identity-relevant information to satisfy employees’ needs for organizational respect and positive connections with the organization.62 Consist with the social identity theory of leadership,28 an ethical leader exhibits their ethical leadership to influence the changes in employees’ self-concept as leader group prototypicality.23,84 Specifically, ethical leadership leverages adequate identity support in organizational recognition and provides employees with positive interpersonal compensation to shape employees’ identities within the organization following co-worker ostracism. Hence, employees gain the opportunity of positive reconnections with the support of leader group prototypicality and are willing to identify their self-identity attached to the organizational memberships. There is empirical support for the positive help of prototypical leaders who carry identity-relevant information in promoting employees to define their identities within the organization.63 Furthermore, with the positive definition of self-concept in the organization, employees are satisfied with self-identity attached to the positive interactions within the organization. They are inclined to put effort into extra-role actions that benefit organizational effectiveness.77 In contrast, employees are difficult to perceive alternative belongingness and value recognition from low ethical leadership to satisfy their needs for identity connection with the organization following experiences of co-worker ostracism. Without the positive connection to identify their self-concept within the organization, ostracized employees lack positive interaction motivation to promote an extra-role behavioral effort to organizations. We propose the following:

Hypothesis 4: Ethical leadership moderates the indirect effect of co-worker ostracism on OCB via three levels of employee self-identity. Specifically, the indirect effect is positive at high levels of ethical leadership but negative at low levels.

Overview of Studies

This research tests how co-worker ostracism and ethical leadership interact to affect ostracized employees’ self-identity and OCB. For effectively manipulating the changes in different levels of co-worker ostracism and ethical leadership to examine this causal relationship between variables, this research employed an experimental vignette methodology85 and designed Study 1. Study 1 manipulated co-worker ostracism and ethical leadership in a between-subjects investigation to ask participants to immerse themselves in a simulated workplace scenario. Participants then responded to relevant questions about employee self-identity and their willingness to OCB. Extant research has introduced the vignette experiment as an effective method to test the causality in the effect of the interaction of workplace ostracism with contextual factors on employees’ outcomes.14,86 Meanwhile, this experimental vignette design in Study 1 responded to the call for data collection and verification by scenario-based experiments to strengthen the persuasiveness of the causal relationship between variables.8,87 Study 1 provided strong evidence of causal prediction to dependent variables, but it only designed a superficially similar experiment scenario, and the external validity of its findings remained insufficient. Indeed, not directly experiencing workplace ostracism creates psychological differences for individuals.88 For generalizing the findings of Study 1 outside of the controlled laboratory environment, Study 2 eliminated the concern about the psychological authenticity of participants in Study 1 and extended the results to full-time employees in a field study.

Study 1: Vignette Experiment

Participants and Procedure

This study focused on ostracizing behaviors of coworkers and the subsequent tendency of ostracized employees to engage in extra-role behaviors, which was embedded in workplace interpersonal interactions. In the experimental context of work-related interpersonal interactions, this study chose MBA students with extensive work experience as appropriate participants to ensure that participants better understood the linkages between variables. Extant research has demonstrated the reliability and validity of using MBA students with work experience as participants in an experimental scenario addressing employee behaviors in the workplace.89 This study selected 150 MBA students enrolled in business management training at a university in China. As participants, they were informed that participation was voluntary and that their responses would remain anonymous. Each participant was given a popular movie ticket as a gift. After providing informed consent, all participants were randomly and averagely divided into four groups in the experimental room, and each group was assigned to one of four vignette scenarios. This vignette scenario manipulated co-worker ostracism and ethical leadership (see the description of the vignette scenario below).

Participants completed a short demographic questionnaire and then read the assigned scenario. After reading the assigned scenario description, they first responded to two questions about its content. One question was to choose the correct company name, preset in the experimental scenario, from three similar names. Another was to ask participants to answer the project name they were working on with their co-workers in the experimental scenario. Then, they answered two items about the degree of ostracism they felt and perceived ethical leadership, which were used in manipulation checks of different experimental scenarios. Finally, participants completed the remaining questionnaires to indicate their self-identity and tendency of OCB towards the organization. For the correctness of the two questions about the company name and project name, results indicated that 28 participants committed errors on either. We removed the 28 participants’ questionnaires with errors, and the final sample included 122 participants (48.4% male).

Vignette Scenarios

Study 1 used a vignette scenario paradigm to examine the proposed hypotheses. It designed the 2×2 factorial between-subject by manipulating ostracism (low versus high) and ethical leadership (low versus high) in vignette scenarios. The ostracism scenario was based on the language exclusion experiment proposed by Hitlan et al.90 Because co-worker ostracism in this study emphasized the ostracizing behaviors that occurred in the interpersonal interactions of daily work, Study 1 made some adjustments to the content of the original experimental scenario. Participants of Study 1 played an employee role and worked for a real estate company’s operations management department. The experimental scenario described the participant’s work experience with co-workers, which was a team project in the past year. In the high ostracism scenario, participants read about how the two other team members recently excluded them from the team project and ignored their requests for help in the daily work. For example, the scenario states: “It seems that your team members ignore your thoughts when they discuss the workload scheduling;” “Despite you request help from them, the two other team members give you the silent treatment;” and “While working overtime, your team members order ‘take-out’ together without asking you what you would like to order”. In the low ostracism condition, participants were given a scenario without obvious silent treatment from co-workers. It detailed how they could gain co-workers’ responses to proposed problem-solving within a reasonable time and engage in daily conversations about team projects.

The manipulation of ethical leadership was based on the Multidimensional Scale developed by Brown et al.24 Information about the participant’s perceived ethical leadership came from the department manager, who was responsible for several project teams and connected with the participant’s daily work in the scenario. In the low condition, participants read the following scenarios: “Your supervisor does not consider the opinions and interests of subordinates while making decisions”, “Your supervisor cannot make fair and balanced decisions regarding work”, and so on. In contrast, in the high condition, participants read the following scenarios: “Your supervisor considers the opinions and interests of subordinates while making decisions”, “Your supervisor always makes fair and balanced decisions regarding work”, and so on. After reading the preset vignette scenarios, participants completed their inclination towards self-identity and OCB.

Measures

Unless indicated otherwise, participants responded to all items using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree).

Manipulated Co-Worker Ostracism

A single item measured the extent of ostracism perceived by participants in the preset scenario: “How excluded did you feel by your work colleague?” This item has been demonstrated to have reliability in examining the manipulated effectiveness in different ostracism scenarios.86

Manipulated Ethical Leadership

The level of ethical leadership experienced by participants in the experimental scenario was measured using the following item: “to what extent did you perceive ethical leadership from your supervisor”. Previous research has indicated that short scales, such as a single item,91 reach reliability and validity for clearly defined concepts.92 Therefore, for conceptual and pragmatic reasons, this study used this scale to realize a manipulation check about different levels of ethical leadership.

Employee Self-Identity

This study measured employee self-identity by Johnson, Selenta, and Lord’s Levels of Self-Concept Scale (LSCS),93 which was a reliable measurement of individual, relational, and collective identities.94,95 It contains five items of individual identity (eg, “I thrive on opportunities to demonstrate that my abilities or talents are better than those of other people”; Cronbach’s α = 0.95), five items of relational identity (eg, “Caring deeply about another person such as a colleague is important to me”; Cronbach’s α = 0.94), and five items of collective identity (eg, “When I become involved in a group project, I do my best to ensure its success”; Cronbach’s α = 0.94).

Organizational Citizenship Behavior

Because the construct of OCB in our research was based on foci of action rather than a beneficiary of the action, we measured participants’ OCB by altruism, voice, and conscientiousness from Farh et al96 which was applicable to participants’ surrounding social context from China. Because these dimensions were highly interrelated and shared common correlates,5,97 this study used an overall composite measurement to measure OCB. A sample item is: “I actively bring forward suggestions that may help the organization run more efficiently or effectively”. Cronbach’s α = 0.97.

Control Variables

Consistent with previous research on workplace ostracism,98,99 Study 1 controlled participants’ age, gender, and organizational tenure. These control variables potentially affect employees’ prosocial behaviors.100,101

Study 1 Results

Manipulation Checks

Study 1 used two one-way between-subjects ANOVAs to examine whether the manipulations were effective in each condition. Participants in the high ostracism condition felt more excluded (M = 5.20; SD = 1.10) than those in the low ostracism condition (M = 2.18; SD = 1.14; F (1,121) = 221.90, p < 0.001]. Moreover, participants perceived more attention under the high levels of ethical leadership (M = 5.36; SD = 1.26) compared with those under the low levels of ethical leadership (M = 2.62; SD = 1.47; F (1,121) = 122.04, p < 0.001]. These results indicated that participants accurately noticed differences between manipulated scenarios.

Hypothesis Test Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and correlations of all variables. Study 1 conducts Hayes’s conditional process analysis102,103 using the regression-based PROCESS macro104 in SPSS to test the hypothesized model in which either the direct or indirect effect of co-worker ostracism on OCB through three levels of employee self-identity is moderated by ethical leadership. This method implies a bootstrap procedure to calculate all potential paths simultaneously and effectively handles the non-normality of interaction terms.86 It combines the analysis of mediation and moderation into one singular analysis, as recommended by methodologists,105,106 which offers a robust strategy for assessing conditional direct and indirect effects to be widely used to investigate moderated mediation model.23,30 Meanwhile, Montani et al73 propose that this method “overcomes the problems associated with Baron and Kenny’s causal steps107 and Sobel’s test, such as low statistical power”.108,109 Results were displayed in Table 2

|

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations of Variables in Study 1 |

|

Table 2 Ordinary Least Squares Regression Model Coefficients in Study 1 |

In Study 1, the interactive effect of ostracism and ethical leadership on OCB (B = 3.01, t = 6.54, p < 0.001) was significant in Table 2 (Model 1). Table 3 also showed that co-worker ostracism was positively associated with OCB when ethical leadership was high (B = 0.72, SE = 0.29, 95% CI: [0.15, 1.29]). In contrast, co-worker ostracism had a negative association with OCB when ethical leadership was low (B = −1.01, SE = 0.32, 95% CI: [−1.64, −0.38]). These results provided support for Hypothesis 1.

|

Table 3 Conditional Direct and Indirect Effects on OCB at Different Levels of Ethical Leadership in Study 1 |

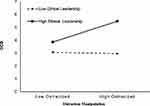

Table 2 (Model 2) showed the moderating effect of ethical leadership on the relationship between co-worker ostracism and three levels of employee self-identity (individual identity: B = 1.11, t = 1.86, p > 0.05; relational identity: B = 2.29, t = 4.21, p < 0.001; collective identity: B = 2.01, t = 4.12, p < 0.001). Figure 2a–2c depicted the association of co-worker ostracism with three levels of employee self-identity at high or low levels of ethical leadership. However, the contingent effect of ostracism on individual identity was not significant when ethical leadership was low. Hypothesis 2 was partially significant. Moreover, the effect of individual identity (B = 0.17, t = 2.58, p < 0.05), relational identity (B = 0.25, t = 3.29, p < 0.01), and collective identity (B = 0.26, t = 3.12, p < 0.01) on OCB were significant, supporting Hypothesis 3.

Hypothesis 4 predicted the mediation effect of employee self-identity moderated by ethical leadership. Based on the path analysis of Model 3, the results in Table 3 indicated that the indirect effect was positive (individual identity: B = 0.18, BootSE = 0.10, 95% BootCI: [0.01, 0.40]; relational identity: B = 0.19, BootSE = 0.11, 95% BootCI: [0.01, 0.44]; collective identity: B = 0.18, BootSE = 0.11, 95% BootCI: [0.01, 0.43]) when ethical leadership was high. In contrast, the indirect effect was negative (individual identity: B = - 0.01, BootSE = 0.09, 95% BootCI: [−0.22, 0.16]; relational identity: B = −0.37, BootSE = 0.18, 95% BootCI: [−0.79, −0.08]; collective identity: B = −0.35, BootSE = 0.18, 95% BootCI: [−0.75, −0.08]) when ethical leadership was low. The conditional indirect relationship was plotted in Figure 3. Overall, Hypothesis 4 was partially supported.

|

Figure 3 The indirect effect of co-worker ostracism on OCB at high and low levels of ethical leadership (Study 1). |

Study 2: Field Study

Participants and Procedure

With the help of the teacher in charge of the student’s social practice course, this study recruited suitable full-time working adults through the social network of 90 university students who have signed up for social practice. This study was in exchange for additional points of social practice to ask students to voluntarily offer the email addresses of not less than 4 full-time employees who were willing to participate in the study. Based on this method, this study recruited 400 full-time employees as participants from financial (12%), education (8%), manufacturing (22%), construction (39%), and electricity (19%). All participants volunteered to participate in this survey and were informed that their responses were confidential and only used in the survey. This study collected the data in three waves to weaken the interaction of variables and common method bias.110,111 In wave 1, Study 2 sent 400 questionnaires to collect information about employees’ demographics (eg, age, gender, organizational tenure, and education), co-worker ostracism, and ethical leadership by e-mail. Study 2 received 375 valid questionnaires from 400 questionnaires in Wave 1, with a response rate of 93.8%. Several studies have verified that workplace ostracism leads to psychological consequences with a 2- to 3-month lag.112,113 Study 2 sent the second questionnaire about employee self-identity to the rest of the 375 respondents two months later and received 328 valid e-mail responses (82%). Meanwhile, Carpenter et al114 provided theoretical support for the construct-related validity of self-rated OCB. Therefore, one month after Wave 2, Study 2 asked 295 respondents from Wave 2 to complete the measurement of OCB by self-reports. 295 valid e-mail responses were received in Wave 3, and the response rate was 73.8%.

Among the final 295 respondents, 64% were men. Regarding age, 29.8% were aged 29 or below, 49.2% were between 30 and 39, 19.3% were between 40 and 49, and 1.7% were aged 50 or above. For the level of education, 11.5% of respondents finished junior college or below, 42.7% held bachelor’s degrees, 44.4% held master’s degrees, and the remaining 1.4% held doctoral degrees. Regarding organizational tenure, 26.4% were less than 1 year, 41.4% were 1 to 3 years, 8.1% were 3 to 5 years, and 24.1% were more than 5 years.

Measures

All measures used a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree).

Co-Worker Ostracism

Study 2 measured co-worker ostracism by a 10-item scale developed by Ferris et al.115 This scale was applied in Wave 1. A sample item is: “My greetings have gone unanswered at work” (Cronbach’s α = 0.97).

Ethical Leadership

Study 2 used a 10-item scale developed by Brown et al24 to measure ethical leadership in Wave 1. The sample item is: “My leader listens to what employees have to say” (Cronbach’s α = 0.96).

Employee Self-Identity

In Wave 2 of Study 2, employee self-identity was assessed by the same scale used in Study 1. Cronbach’s α was 0.89 (individual identity), 0.89 (relational identity), and 0.92 (collective identity).

Organizational Citizenship Behavior

The same 9-item scale used in Study 1 was applied in Wave 3 of Study 2. Cronbach’s α = 0.95.

Control Variables

In addition to the same control variables used in Study 1, Study 2 controlled respondents’ education. Education potentially affects employee behavioral responses.100

Study 2 Results

Preliminary Analyses

Before testing the proposed hypotheses, Study 2 first used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)116,117 to assess the model fit with six factors (co-worker ostracism, ethical leadership, individual identity, relational identity, collective identity, and OCB). The fit of the six-factor model showed significant fit with data (χ2/df = 1.5, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.96; RMSEA = 0.03). In comparison, when all items were loaded onto a single factor, the one-factor model did not fit with the data (χ2/df = 10.71, CFI = 0.28, TLI = 0.20; RMSEA = 0.15). These results verified the distinctiveness of our variables.

The variables were self-reported in Study 2, which caused common method variance (CMV).112 This study used several diagnostics to confirm whether the collected data were affected by CMV. First, the result of Harman’s one-factor test showed that the first factor accounted for 28.24% of the variance. Moreover, a single-factor CFA showed a poor fit with the data. Finally, Study 2 added a common latent factor to the six-factor measurement model. The measurement model with a common latent factor (Δχ2 = 20.32, p < 0.05) was significant. Overall, CMV had no threat to our subsequent analysis.

Hypothesis Test Results

Table 4 shows the correlations of variables in Study 2. Study 2 used the same Hayes’ conditional process approach as Study 1 to calculate the hypothesized model.

|

Table 4 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations of Variables in Study 2 |

According to the regression results shown in Table 5 (Model 1), the Ostracism × Ethical leadership interaction had a positive effect on OCB (B = 0.39, t = 9.05, p < 0.001). Specifically, co-worker ostracism was positively related to employees’ OCB when ethical leadership was high (B = 0.23, SE = 0.08, p < 0.01) and negatively related to their OCB when ethical leadership was low (B = −0.38, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001). Therefore, Hypothesis 1 was supported.

|

Table 5 Results of Moderated Mediation Analysis in Study 2 |

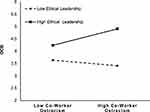

As shown in Table 5 (Model 2), ethical leadership had a positive interaction with co-worker ostracism in predicting three levels of employee self-identity (individual identity: B = 0.18, t = 4.82, p < 0.001; relational identity: B = 0.24, t = 6.38, p < 0.001; collective identity: B = 0.23, t = 6.43, p < 0.001). These interactive effects were plotted in Figure 4a–4c. Based on simple slope analyses, the conditional effect of co-worker ostracism on individual identity (B = 0.17, SE = 0.07, p < 0.05), relational identity (B = 0.23, SE = 0.07, p < 0.01), and collective identity (B = 0.22, SE = 0.07, p < 0.01) was positive when ethical leadership was high, and negative when ethical leadership was low (individual identity: B = −0.22, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001; relational identity: B = −0.30, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001; collective identity: B = −0.30, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001). Overall, the results were consistent with Hypothesis 2. For Hypothesis 3, three levels of employee self-identity were positively related to participants’ OCB (individual identity: B = 0.17, t = 2.54, p < 0.05; relational identity: B = 0.20, t = 3.03, p < 0.01; collective identity: B = 0.16, t = 2.28, p < 0.05), supporting Hypothesis 3.

Hypothesis 4 predicted that the indirect effect of co-worker ostracism on employees’ OCB depended on the conditional moderation of ethical leadership. In Table 6, the conditional indirect effect was significantly positive when ethical leadership was high (individual identity: B = 0.03, BootSE = 0.02, 95% BootCI:[0.00, 0.07]; relational identity: B = 0.05, BootSE = 0.02, 95% BootCI:[0.01, 0.10]; collective identity: B = 0.03, BootSE = 0.02, 95% BootCI:[0.01, 0.08]), and significantly negative when ethical leadership was low (individual identity: B = −0.04, BootSE = 0.02, 95% BootCI:[−0.08, −0.01]; relational identity: B = −0.06, BootSE = 0.02, 95% BootCI:[−0.11, −0.02]; collective identity: B = −0.05, BootSE = 0.02, 95% BootCI:[−0.09, −0.01]). Moreover, the index of moderated mediation102 verified that ethical leadership positively moderated the indirect ostracism–OCB relationship through three levels of employee self-identity (individual identity: INDEX = 0.03, BootSE = 0.01, 95% BootCI: [0.01, 0.06]; relational identity: INDEX = 0.05, BootSE = 0.02, 95% BootCI: [0.01, 0.09]; collective identity: INDEX = 0.04, BootSE = 0.02, 95% BootCI: [0.01, 0.07]). Study 2 plotted this conditional indirect relationship in Figure 5, wherein the relationship was positive at high levels of ethical leadership and negative at low levels of ethical leadership. Overall, Hypothesis 4 was supported.

|

Table 6 Conditional Direct and Indirect Effects on OCB at Different Levels of Ethical Leadership in Study 2 |

|

Figure 5 The indirect effect of co-worker ostracism on OCB at high and low levels of ethical leadership (Study 2). |

General Discussion

In Study 1, participants immersed themselves into the preset role of an employee in one of the 2×2 factorial between-subjects scenarios by manipulating different levels of workplace ostracism and ethical leadership. Then, they responded to related questions about employee self-identity and reported their willingness to OCB. In study 2, participants reported similar responses based on real experiences after being ostracized by co-workers and perceiving ethical leadership in their daily working environment. This multi-study design guaranteed the validity of causality between variables in the manipulated scenario experiments. Meanwhile, it realized generalization and replication of thelaboratorial findings in the field setting and supported external validity.23

Both studies were indispensable in this research, and the results of Study 2 resembled those of Study 1, strengthening the credibility of the core idea that ethical leadership transmitted the damage of co-worker ostracism to OCB and promoted ostracized employees to engage in OCB through the realization of employee self-identity. Hypothesis 1 was confirmed in Study 1 and Study 2, demonstrating that the high level of ethical leadership enabled employees to positively engage in OCB following experiences of co-worker ostracism, and the negative effect of co-worker ostracism on OCB still existed at the low level of ethical leadership. Tests of Hypothesis 2 produced an interesting finding. The results of Study 2 demonstrated that the relationship between co-worker ostracism and individual identity was significantly negative at the low level of ethical leadership, which was consistent with Hypothesis 2. However, this relationship was non-significant and showed a positive trend in Study 1, albeit not in the predicted direction. The reason is that the preset ostracism scenario highlights the interpersonal isolation and friction that fit the research background and cannot make participants feel the actual competitive pressure between peers like the actual working environment. This ostracism scenario mitigates participants’ focus on gaining prestige among peers to be advantageously compared to peers. Therefore, participants lack vital needs for socioemotional awards (eg, superiority over peers)118 in the simulative scenario experiment and are unable to be as susceptible to co-worker ostracism as the statement of Robinson et al9 that ostracism enables the prized objective of becoming influential and important among peers to be less likely to achieve. Participants maintained positive perceptions of personal uniqueness and self-value to define individual identity in the organization even after experiencing co-worker ostracism. This positive trend for ostracized individuals to define individual identity under the low level of ethical leadership in Study 1 confirmed the concern of Balliet, Ferris14 about the insufficiency of psychological authenticity of participants in the experimental scenario design relative to the field study. To compensate for the weakness of Study 1, this research designed Study 2 to empirically test and support the proposed Hypothesis 2 in the field setting. Tests for Hypothesis 3 were consistent in Study 1 and Study 2 and showed a significantly positive relationship between three levels of employee self-identity and OCB. Furthermore, due to the non-significant effect of co-worker ostracism on individual identity at the low level of ethical leadership in Study 1, the conditional effect of low ethical leadership on the indirect relationship between co-worker ostracism and OCB through individual identity was non-significant in Study 1. Although the conditional moderation of low ethical leadership in affecting the mediating role of individual identity was not significant as Study 2, this research nevertheless found that this indirect relationship was as negative as Study 2 at the low level of ethical leadership. The complementarity between the two studies supported hypothesis 4, as presented in the results of Study 2.

This research combined a scenario experiment with a field study to verify and support all the proposed hypotheses empirically. Specifically, this research found that ostracized employees who perceived high ethical leadership had a positive interpersonal foundation to enhance their three levels of self-identity and thus performed pro-social connections related to more OCB. In contrast, when ethical leadership was low, ostracized employees without alternative interpersonal support were difficult to recognize their self-identity as an insider. They socially distanced themselves from the organization to avoid further ostracized encounters and reduced their tendency to engage in OCB. Therefore, these findings provide cross-validate support for the proposed moderated mediation model.

Theoretical Contributions

These findings have theoretical contributions to the literature regarding the association of co-worker ostracism with OCB. One contribution is that this research introduces an identity perspective to identify the novel moderating role of ethical leadership in promoting employees’ participation in OCB after experienceof co-worker ostracism. In the Chinese context, employees tend to recognize positive interpersonal interactions as the representative of career success in work settings.10,119 Especially, the Chinese cultural characteristic emphasizing the “Chaxu” increases employees’ perception of supervisor-subordinate guanxi that impacts interpersonal interactions in the workplace.8,120 It provides an ideal setting for this research to magnify the buffering effect of ethical leadership on the ostracism-OCB relationship and support a more remarkable finding. This research found that the high level of ethical leadership transitioned the harmful co-worker ostracism and satisfied ostracized employees’ needs for interpersonal interactions to support their willingness to take extra-role actions. In contrast, the low level of ethical leadership was difficult to provide ostracized employees with the opportunity to reconnection with the organization as insiders, leading them to choose adverse social withdrawal related to less OCB. Such a finding lends credence to previous studies showing the negative relationship between workplace ostracism and OCB for employees without a sense of belongingness.18,59,121 Meanwhile, it is consistent with extant research highlighting the identity-relevant information conveyed by ethical leadership in effectively supporting employees’ definition of their identities within the organization and providing close employee-organization relationships to foster their pro-social behaviors.23,29 Furthermore, it extends the identity implications of ethical leadership in inspiring ostracized employees’ positive tendency to OCB. Following the social identity theory of leadership,27 relevant research found that ethical leadership, as leader group prototypicality, speaked louder to shape employees’ identities within the organization and displayed fair treatment and acceptance as representative of the organization to inspire employees to adopt more OCB.23,30 As Wang, Xu122 indicate, ethical leadership enabled employees to perceive positive interpersonal interactions and moral guidance from two-way communication with the organizational representative. Indeed, Li, Janmaat21 proposed the powerful support of the supervisor communication satisfaction, relative to co-worker communication satisfaction, in enabling employees to perceive being embedded in the organization and the meaningfulness of work efforts, which promoted employees to engage in more OCB. Accordingly, based on the social identity theory of leadership,27 this research demonstrates that the identity-relevant cues conveyed by ethical leadership help employees get rid of the damage of co-worker ostracism to the belongingness by providing positive communication and alternative interpersonal relationships with leader group prototypicality to satisfy employees’ need to identify themselves with the organization. Ostracized employees gain the satisfaction of belongingness to be willing to make extra-role efforts to benefit organizational effectiveness.18 This research copes with the powerlessness of previous research on leveraging employees’ own influence to regain connection with the organization and foster ostracized employees’ tendency to take extra-role efforts.18,19 It responds to the call of Hershcovis and Reich41 to focus on leadership interventions in guiding employees’ behavioral responses to co-worker ostracism. Hence, the original findings of this research broaden the sight by introducing an identity perspective to identify the influential buffering role of ethical leadership in the relationship between co-worker ostracism and OCB and realize the accessibility of transitioning the harmful ostracism and promoting ostracized employees’ willingness to OCB. Moreover, it enriches the previous research about the boundary moderation of ethical leadership in alleviating the damage of co-worker ostracism and influencing employees’ behavioral responses.41

Additionally, drawing the social identity theory of leadership,27 the original finding reveals that ethical leadership exerts identity-relevant inference for shaping employees’ identities within the organization to buffer ostracized employees’ inability to identify themselves with the organization following experience of co-worker ostracism and provide alternative belongingness to inspire ostracized employees to take more extra-role actions. This research provides a more profound account of the ostracism–OCB relationship by further uncovering the mediating role of three levels of employee self-identity to strengthen the buffering value of ethical leadership. For a complete understanding of defining an individual’s identities related to socially interacting with the organization, some scholars have highlighted that accounting for the simultaneity of three levels of employee self-identity (individual, relational, and collective identities) is sufficient.33,37 This research simultaneously considers the identifying process of three levels of employee self-identity in the relationship between co-worker ostracism and OCB. It clarifies that ethical leadership transitions the harmful ostracism and promotes ostracized employees’ participation in more OCB by influencing how ostracized employees gain effective identity-relevant curs for identifying their different identities within the organization. The results of this research provide empirical support for the indirect relationship between co-worker ostracism and OCB that the high level of ethical leadership inspires the realization of positively defining three levels of employee self-identity for those who experience co-worker ostracism. Then, realizing employee self-identity in the organization leads to a positive tendency related to more OCB. Moreover, this research simultaneously demonstrates the positive effect of three levels of employee self-identity on OCB, extending previous research about the relationship between one level of employee self-identity and OCB.78–80 Specifically, these empirical findings state that ostracized employees suppress the interpersonal isolation stressor to positively categorize themselves into the organization and define their identities because they perceive the support of ethical leadership in providing opportunities for alternative belongingness and reconnections with leader group prototypicality. As noted by Marstand et al,77 employees with positive self-identity realize the close connection with the organization to be willing to share benefits with the organization and make more extra-role efforts. This research shows that the ostracism–OCB relationship research benefits from the social identity theory of leadership to uncover the mediating process of three levels of employee self-identity moderated by ethical leadership from an identity perspective.

Practical Implications

The initial findings also have important practical implications. The ambiguous nature of co-worker ostracism involves the omission of socially engaging others that may be oblivious to social niceties in the workplace. This non-purposeful form of co-worker ostracism may be frequent in the teamwork and has no harmful intention.13 However, because the Chinese have strong interpersonal ties and focus on guanxi management, they are more sensitive to potential signals that co-worker ostracism undermines their close connections with others in the workplace.8,10 Accordingly, this inaction of interpersonal interactions is difficult to guarantee that ostracized employees are not psychologically harmed in China. They may be difficult to maintain harmonious interpersonal relationships with co-workers and will be less motivated in teamwork. As Wu et al119 proposed, workplace ostracism was more harmful to the effective development of teamwork in China, causing huge losses to Chinese organizations. To avoid more serious ostracism harm, this research indicates that organizational leaders need to understand how to reduce inadvertently engaging in ostracism because co-workers are lost in thought related to work tasks or forgetful of new employees on a work memo. As such, organizations need to positively conduct regular work workshops to strengthen cooperation and communication among employees through effective group discussions. Meanwhile, organizations can develop a training program about shared understandings of normative social engagement to assist employees in avoiding one-sided misunderstandings of being slighted by co-workers who are merely acting on a different social script. Furthermore, co-worker ostracism is low-intensity inaction behavior that is difficult to be noticed by organizational leaders and bound by formal norms, thus, making it hard for organizations to eliminate. To avoid the disruption of the interpersonal relationship caused by the seemingly trivial experiences of ostracism, organizations benefit by recruiting and developing leaders with high ethical leadership, such as leadership development workshops. Specifically, organizations attach importance to ethical leadership development to promote two-way communication with employees, especially those excluded by co-workers, in team workshops. It helps them regain a sense of belonging within the organization from organizational acceptance.

Limitations and Future Research

This research also has some limitations. One limitation is a lack of control over other mediation mechanisms in the ostracism–OCB relationship. Based on the social identity theory of leadership, our research suggests that employee self-identity mediates the effect of co-worker ostracism on OCB under the support of ethical leadership. Other mediation roles, such as empathy, also focus on the perception of the reconnection process to explain the association of exclusion with pro-social tendency based on reciprocal alliances.123 Besides, based on cognitive consistency theory, Chung, Yang124 demonstrated that organization-based self-esteem mediated the relationship between co-worker ostracism and helping behaviors through self-evaluations of organizational worth. Following other perspectives in addressing the underlying mechanism of co-worker ostracism and beneficial workplace behaviors, we encourage future research to use other theoretical foundations to probe the ostracism–OCB relationship.

Besides, our research ignores the changes in ethical leadership before and after being ostracized by co-workers. This research only focuses on the effect of ethical leadership at different levels. Future studies are encouraged to examine whether the change affects our proposed hypotheses. Specifically, in the scenario study, we can measure participants’ perceived ethical leadership before exposing them to the ostracism condition and then measure it again. However, there will be an unexpected effect on manipulating perceived ethical leadership when participants respond to it twice. Furthermore, when measuring the change of perceived ethical leadership in the field study, it is challenging to control when ostracizing behaviors occur for measuring perceived ethical leadership twice.

Conclusion

Based on the social identity theory of leadership, this research is the first to examine the buffering role of ethical leadership in transitioning the damage of co-worker ostracism to OCB and promoting ostracized employees’ positive social connections related to more OCB. This research further reveals the identifying process of three levels of employee self-identity to strengthen the moderating effect of ethical leadership on the indirect relationship between co-worker ostracism and OCB from an identity perspective. Thus, this research enriches our understanding that the identity-relevant information from ethical leadership compensates for employees’ needs for interpersonal interactions to help them positively identify their identities within the organization following experience of co-worker ostracism. Ostracized employees perceiving the high level of ethical leadership are willing to participate in more OCB.

Ethical Statement

Ethical approval was supported by Research Office at Tianjin University. We conducted that this questionnaire survey did not involve unethical behavior based on institutional guidelines and national laws and regulations. We informed all participants that voluntary participation and completed surveys indicated that their informed consent has been obtained for our research. We guaranteed that participants’ responses were anonymous and confidential.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 71872126).

Disclosure

All authors declare no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Das SC. Influence of organizational citizenship behaviour (OCB) on organizational effectiveness: experiences of banks of India. J Strateg Hum Resour Manag. 2021;9(2):1–10.

2. Pio RJ, Tampi JRE. The influence of spiritual leadership on quality of work life, job satisfaction and organizational citizenship behavior. Int J Law Manag. 2018;60(2):757–767. doi:10.1108/ijlma-03-2017-0028

3. Organ DW. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books; 1988.

4. Bizri RM, Hamieh F. Beyond the “give back” equation the influence of perceived organizational justice and support on extra-role behaviors. Int J Organ Anal. 2019;28(3):699–718. doi:10.1108/ijoa-07-2019-1838

5. Farh JL, Zhong CB, Organ DW. Organizational citizenship behavior in the People’s Republic of China. Organ Sci. 2004;15(2):241–253. doi:10.1287/orsc.1030.0051

6. Lim YH, Kee DMH, Lai XY, et al. Organizational culture and customer loyalty: a case of Harvey Norman. Asia Pac J Manag Educ. 2020;3(1):47–62. doi:10.32535/apjme.v3i1.743

7. Xia A, Wang B, Song B, Zhang W, Qian J. How and when workplace ostracism influences task performance: through the lens of conservation of resource theory. Hum Resour Manag J. 2019;29(3):353–370. doi:10.1111/1748-8583.12226

8. He P, Wang J, Zhou H, Liu Q, Zada M. How and when perpetrators reflect on and respond to their workplace ostracism behavior: a moral cleansing lens. Psychol Resour Behav Manag. 2023;16:683–700. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S3

9. Robinson SL, O’Reilly J, Wang W. Invisible at work: an integrated model of workplace ostracism. J Manage. 2013;39(1):203–231. doi:10.1177/0149206312466141

10. Zhu H, Lyu Y, Deng X, Ye Y. Workplace ostracism and proactive customer service performance: a conservation of resources perspective. Int J Hosp Manag. 2017;64:62–72. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.04.004

11. Lyu Y, Zhu H. The predictive effects of workplace ostracism on employee attitudes: a job embeddedness perspective. J Bus Ethics. 2019;158(4):1083–1095. doi:10.1007/s10551-017-3741-x

12. Ferris DL, Chen M, Lim S. Comparing and contrasting workplace ostracism and incivility. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2017;4:315–338. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032516-113223

13. Scott KL, Tams S, Schippers MC, Lee K. Opening the black box: why and when workplace exclusion affects social reconnection behaviour, health, and attitudes. Eur J Work Organ Psy. 2015;24(2):239–255. doi:10.1080/1359432X.2014.894978

14. Balliet D, Ferris DL. Ostracism and prosocial behavior: a social dilemma perspective. Organ Behav Hum Dec. 2013;120(2):298–308. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2012.04.004

15. Haldorai K, Kim WG, Li JJ. I’m broken inside but smiling outside: when does workplace ostracism promote pro-social behavior? Int J Hosp Manag. 2022;101:103088. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.103088

16. Howard MC, Cogswell JE, Smith MB. The antecedents and outcomes of workplace ostracism: a meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2020;105(6):577–596. doi:10.1037/apl0000453

17. Mok A, De Cremer D. The bonding effect of money in the workplace: priming money weakens the negative relationship between ostracism and prosocial behaviour. Eur J Work Organ Psy. 2016;25(2):272–286. doi:10.1080/1359432x.2015.1051038

18. Wu CH, Liu J, Kwan HK, Lee C. Why and when workplace ostracism inhibits organizational citizenship behaviors: an organizational identification perspective. J Appl Psychol. 2016;101(3):362–378. doi:10.1037/apl0000063

19. Ferris DL, Fatimah S, Yan M, Liang LH, Lian H, Brown DJ. Being sensitive to positives has its negatives: an approach/avoidance perspective on reactivity to ostracism. Organ Behav Hum Dec. 2019;152:138–149. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2019.05.001

20. Ferris DL, Brown DJ, Heller D. Organizational supports and organizational deviance: the mediating role of organization-based self-esteem. Organ Behav Hum Dec. 2009;108(2):279–286. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2008.09.001

21. Li J, Janmaat J. Is supervisory communication more important than co-worker communication for employees’ engagement behavior in China? A moderated mediation analysis. Work. 2023;75(1):253–263. doi:10.3233/WOR-211425

22. Novitasari D, Riani AL, Suyono J, Harsono M. The moderation role of ethical leadership on organisational justice, professional commitment, and organisational citizenship behaviour among academicians. Int J Work Organ Emotion. 2021;12(4):303–324. doi:10.1504/IJWOE.2021.120718

23. Gerpott FH, Van Quaquebeke N, Schlamp S, Voelpel SC. An identity perspective on ethical leadership to explain organizational citizenship behavior: the interplay of follower moral identity and leader group prototypicality. J Bus Ethics. 2019;156(4):1063–1078. doi:10.1007/s10551-017-3625-0

24. Brown ME, Trevino LK, Harrison DA. Ethical leadership: a social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organ Behav Hum Dec. 2005;97(2):117–134. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.03.002

25. Su C, Ng WHT. Does being envied and ostracized make employees unethical?

26. Kershaw C, Rast DE

27. Hogg MA, van Knippenberg D, Rast DE

28. Hogg MA, van Knippenberg D. Social identity and leadership processes in groups. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Elsevier Academic Press; 2003:1–52.

29. Turner JR, Chacon-Rivera MR. A theoretical literature review on the social identity model of organizational leadership. Adv Dev Hum Resour. 2019;21(3):371–382. doi:10.1177/1523422319851444

30. Costa S, Daher P, Neves P, Velez MJ. The interplay between ethical leadership and supervisor organizational embodiment on organizational identification and extra-role performance. Eur J Work Organ Psy. 2021;1–12. doi:10.1080/1359432x.2021.1952988

31. Brewer MB, Gardner W. Who is this “we”? Levels of collective identity and self representations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;71(1):83–93. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.71.1.83

32. Poon KT, Chen Z, Wong WY. Beliefs in conspiracy theories following ostracism. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2020. doi:10.1177/0146167219898944

33. Biddlestone M, Green R, Cichocka A, Sutton R, Douglas K. Conspiracy beliefs and the individual, relational, and collective selves. Soc Pers Psychol Compass. 2021. doi:10.1111/spc3.12639

34. Evans MB, McLaren C, Budziszewski R, Gilchrist J. When a sense of “we” shapes the sense of “me”: exploring how groups impact running identity and behavior. Self Identity. 2019;18(3):227–246. doi:10.1080/15298868.2018.1436084