Back to Journals » Open Access Emergency Medicine » Volume 12

Ileosigmoid Knotting: A Rare Cause of Intestinal Obstruction and Bowel Ischemia—Case Report with Literature Review

Authors Shuaib A , Khairy A , Aljasmi M , Alaa Sallam M, Abdulsalam F

Received 18 February 2020

Accepted for publication 25 April 2020

Published 8 June 2020 Volume 2020:12 Pages 155—158

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/OAEM.S250291

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Bo Løfgren

Abdullah Shuaib, Ahmed Khairy, Mohammed Aljasmi, Mohamed Alaa Sallam, Fareed Abdulsalam

Department of Surgery, Jahra Hospital, Jahra, Kuwait

Correspondence: Abdullah Shuaib

Email [email protected]

Abstract: Ileosigmoid knotting, also known as compound volvulus or double volvulus, is a rare surgical emergency causing intestinal obstruction. Principally, it is a closed-loop intestinal obstruction that involves the sigmoid and ileum. It is considered a rare cause of intestinal obstruction. Differentiation of ileosigmoid knot from simple sigmoid volvulus is important because endoscopic decompression in ileosigmoid knot might be hazardous and even fatal. Endoscopic decompression of ileosigmoid knot may lead to perforation or injury. The mortality rate of ileosigmoid knot in general may reach 48%. We present a case of a 30-year-old male patient who presented with ileosigmoid knot at our emergency room. The aim of reporting this case is to increase understanding of the condition to promote earlier diagnosis.

Keywords: ileosigmoid knotting, compound volvulus, double volvulus

Introduction

Ileosigmoid knotting, also known as compound volvulus or double volvulus, is a rare surgical emergency causing intestinal obstruction.1–3 Principally, it is a closed-loop intestinal obstruction that involves the sigmoid and ileum.4 It may rapidly progress to a gangrenous state in both the sigmoid and the ileum.1 It was first described in the literature by Parker in 1845.1 The aim of reporting this case is to increase understanding of the condition to promote earlier diagnosis. It is important to differentiate between simple sigmoid volvulus and ileosigmoid knotting because endoscopic decompression is contraindicated in ileosigmoid knotting.

Case

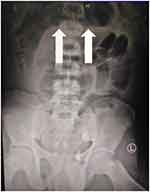

A 30-year-old male presented with diffuse abdominal pain and constipation of 2-day duration. The patient reported no history of blunt trauma or previous surgeries. On clinical examination, the patient was conscious, agitated and disoriented with vital signs including pulse 170 bpm, blood pressure 80/53 mmHg, and saturation 99%. A chest examination was unremarkable. The patient’s abdomen was distended and tense with signs of peritonitis. Laboratory investigations revealed a white blood count of 23x109 and Lactate 5.6mmol/L. A chest x-ray showed no signs of pneumonia or pneumothorax. An erect abdominal x-ray revealed a dilated bowel (see Figure 1). The patient was resuscitated with aggressive intravenous fluid therapy and broad-spectrum antibiotics. The patient was admitted to the surgical intensive care unit to stabilize his condition. We shifted the patient to the operative theater after achieving relative stabilization (pulse 120 bpm and blood pressure 105/60 mmHg). An exploratory laparotomy was performed and revealed the distal ileum knotted around the base of the sigmoid loop base (see Figures 2 and 3). The closed sigmoid loop and the knotted distal ileum were gangrenous. Ileum segment resection and sigmoid resection were performed, which left 10 cm of terminal ileum. End functional ileostomy and non-functional colostomy (mucus drainage of the colon) were positioned through the skin. Anastomosis was not performed due to the hemodynamic instability of the patient’s condition. The abdomen was laid open due to extensive bowel edema and to prevent abdominal compartment syndrome. The patient had a subsequent second-look operation on post-operative day two, which revealed subsiding general bowel edema with unremarkable abdominal cavity. The midline laparotomy wound was partially closed. The patient was shifted to the surgical intensive care unit with nasogastric tube and urinary bladder catheter. Feeding via nasogastric tube was initiated on the second day post-operatively. Full closure of the laparotomy wound was achieved on post-operative day six. The post-operative period was uneventful. Normal oral diet was initiated on the six post-operative days and shifted to surgical ward. A re-continuation surgery of the bowel was performed two months later. The patient was discharged on the 7th post-operative day of the A re-continuation surgery.

|

Figure 1 White arrows indicate the closed sigmoid loop. |

|

Figure 2 Gangrenous closed-loop sigmoid. |

|

Figure 3 White arrows indicate ileum knot on sigmoid mesentery; blue arrow indicates gangrenous sigmoid. |

Discussion

The pathogenesis of ileosigmoid knot is dependent on three factors: 1) a long small bowel mesentery with free mobile small bowel, 2) a long sigmoid with a narrow pedicle, and 3) a bulky diet with the presence of an empty small bowel.1,5 Some studies promote the theory that a bulky diet may progress to the proximal jejunum and increase the mobility of the small bowel and fall in the left lower quadrant of the abdomen.5 Loops of small bowel may rotate around the narrow pedicle of the sigmoid, and further peristalsis progresses the rotation to a closed loop of intestine.5 There are secondary factors besides the anatomical factors mentioned above, such as late pregnancy, trans-mesenteric herniation, meckel diverticulitis with band, and ileocecal intussusceptions.5 It is reported that ileosigmoid knot is predominantly seen in certain African, Asian, and Middle-East nations and rarely in white populations.1,3,5 Ileosigmoid knot is classified into three types (Table 1).1,6 Atamanalp has proposed a new classification based on the age of the patient, associated diseases, and the presence of gangrenous bowel (Table 2).7

|

Table 1 Ileosigmoid Knot Classification |

|

Table 2 New Classification of Ileosigmoid Knot Proposed by Atamanalp |

The diagnosis of ileosigmoid knot is difficult to establish due to its infrequent and rare presentation.3,8 Ileosigmoid knot can be mistaken radiographically as simple sigmoid volvulus, which may lead to attempts to perform endoscopic decompression by a sigmoidoscope.1 Endoscopic decompression of ileosigmoid knot may lead to perforation or injury.1 The mortality rate of ileosigmoid knot in general may reach 48%.9

Initial management of ileosigmoid knot begins with aggressive intravenous fluid resuscitation and acid-base imbalance correction.10 Surgical intervention should follow after the achievement of hemodynamic stability.10 Antibiotic therapy should be implemented in the pre- and post-operative periods for 5–7 days with, for example, cephalosporins, metrodanatzol, and aminoglycosides.10 Various surgical procedures to manage ileosigmoid knot are mentioned in the literature.1 The anatomical and pathological findings intra-operative dictate the surgical procedure.1 The most common procedure performed is ilea and sigmoid resection with primary enteroenteric anastomosis ileum and Hartmann’s procedure/colostomy for descending colon, if both ileum and sigmoid are gangrenous.1 In our case, primary anastomosis was not performed due to a rest terminal ileum less than 10 cm from the ileocecal valve.

Conclusion

Ileosigmoid knotting is a rare cause of intestinal obstruction and bowel ischemia. It is important to differentiate between ileosigmoid Knott and simple sigmoid volvulus to avoid morbidity. Computer tomography may facilitate early diagnosis. Surgical intervention in general includes bowel resection with or without primary anastomosis.

Consent

Written informed consent was provided by the patient to have the case details and any accompanying images published.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Mandal A, Chandel V, Baig S. Ileosigmoid knot. Indian J Surg. 2012;74(2):136–142. doi:10.1007/s12262-011-0346-y

2. Adili W, Jm M, Bm N. The ileosigmoid knot: a case report. Ann Afr Surg. 2014;11(2):1.

3. Lee S, Park YH, Won YS. Case report the ileosigmoid knot: ct findings. AJR. 2000;174(3):685–687. doi:10.2214/ajr.174.3.1740685

4. Al-qahtani J, Faidah A, Yousif M, Kurer MA, Ali SM. Ileosigmoid knotting, rare cause of intestinal obstruction and gangrene. Open Access J Surg. 2017;7(3):8–11. doi:10.19080/OAJS.2017.07.555712

5. Machado NO. Ileosigmoid knot: a case report and literature review of 280 cases. Ann Saudi Med. 2009;29(5):402–406. doi:10.4103/0256-4947.55173

6. Alver O, Oren D, Tireli M, Kayabaşi B, Akdemir D. Ileosigmoid knotting in Turkey. Review of 68 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36(12):1139–1147. doi:10.1007/bf02052263

7. Atamanalp SS, Oeztuerk G, Aydinli B, et al. A new classification for ileosigmoid knotting. Turk J Med Sci. 2009;39(4):541–545. doi:10.3906/sag-0810-1

8. Mungazi GS, Mutseyekwa B, Sachikonye M. A rare occurrence of viability of both small and large bowel in ileosigmoid knotting: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;49:1–3. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2018.05.024

9. Nagappan RN. A rare case of ileo-sigmoid knotting compound volvulus case report. Univ J Surg Surg Spec. 2019;5(5):4–7.

10. Tokta O, Çim N. Ileosigmoid knot as a cause of acute abdomen at 28 weeks of pregnancy: a rare case report. East J Med. 2017;22(3):110–113. doi:10.5505/ejm.2017.35220

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.