Back to Journals » Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management » Volume 19

Identifying the Risk Factors for Postoperative Sore Throat After Endotracheal Intubation for Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

Authors Zheng ZP, Tang SL, Fu SL, Wang Q, Jin LW, Zhang YL, Huang RR

Received 8 November 2022

Accepted for publication 19 January 2023

Published 10 February 2023 Volume 2023:19 Pages 163—170

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S396687

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Deyun Wang

Zhou-peng Zheng,1– 4 Su-lin Tang,1– 4 Shao-lan Fu,1– 4 Qian Wang,1– 4 Li-wei Jin,1– 4 Yan-li Zhang,1– 4 Rong-rong Huang1– 4

1Department of Anesthesiology, Stomatology Hospital, School of Stomatology, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou, 310,000 People’s Republic of China; 2Zhejiang Provincial Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, Hangzhou, 310,000 People’s Republic of China; 3Key Laboratory of Oral Biomedical Research of Zhejiang Province, Hangzhou, 310,000 People’s Republic of China; 4Cancer Center of Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, 310,000 People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Rong-rong Huang, Stomatology Hospital, School of Stomatology, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, No. 166, Qiutao North Road, Shangcheng District, Hangzhou, People’s Republic of China, Email [email protected]

Objective: To identify risk factors for postoperative sore throat (POST) after general anesthesia in oral and maxillOfacial surgery.

Material and Methods: This study is a retrospective cohort design study. We enrolled patients with oral and maxillofacial surgery who underwent endotracheal intubation under general anesthesia in the Stomatology Hospital, Zhejiang University School Of Medicine between April 2020 and April 2021. They were divided into the POST group and the without POST group. The distribution Of various characteristics in the two groups was firstly analyzed. Then, logistic regression analysis was performed to explore the independent predictors for POST occurrence. Following this, logistic regression and random forest models were constructed and their performance was evaluated to predict POST occurrence.

Results: A total of 891 participants were enrolled in the study. Female gender and cough during extubation were significantly associated with increased POST occurrence in multivariate analysis (all P < 0.05). Stratified logistic regression analysis results showed that the female gender was an independent predictor for POST occurrence in the 4≤age≤ 14 and 14

Conclusion: This research reveals female gender and cough during extubation as potential risk factors for POST occurrence, which may provide guidance for the effective prevention of POST in oral and maxillofacial surgery.

Keywords: oral and maxillofacial surgery, postoperative sore throat, female gender, cough during extubation, predictors

Introduction

In the case of oral and maxillofacial surgery, general anesthesia is commonly used for major surgical procedures and invasive surgical operations.1 Endotracheal intubation is an essential operation to secure airway patency and reduce gastric reflux and pulmonary aspiration risk.2 General anesthesia with endotracheal intubation is overall safe but has countless complications, which may affect the general condition of patients and prolong the postoperative hospital stay.3 The incidence of postoperative complications might be related to surgical procedures and general physical health. People having serious medical conditions such as high blood pressure, smoking and stroke can be aggravating factors for anesthesia.4 Currently, anesthetic risks have markedly reduced due to the discovery of advanced anesthetic techniques and sophisticated monitoring equipment.5 However, the incidence of postoperative complications has not changed significantly.6

Postoperative sore throat (POST) is a common consequence of general anesthesia after endotracheal intubation with an incidence varying from 15% to 64%.7,8 The symptoms of POST include pain and discomfort, cough, hoarseness, and laryngitis, which may be the result of inflammation caused by mucosal damage during airway fixation.9,10 Its etiology is believed to involve mucosal dehydration, trauma from tracheal intubation, and mucosal erosion caused by tracheal tube cuff pressure.11 Although clinicians often regarded POST as a relatively minor complication in the past, it leads to a prolonged hospital stay, decreased patient satisfaction, and an increased number of medical complaints.12 Therefore, more and more attention has been paid to the prevention and treatment of POST. A variety of factors have been identified to be associated with POST, such as cuff pressure, surgical sites, operation duration, female gender, and the size of the endotracheal tube used.13 In addition, multiple attempts at laryngoscopy and younger age were closely correlated with an increased risk of POST.14,15 However, there is a lack of research on the risk factors predicting POST occurrence in patients undergoing oral and maxillofacial surgery.

This study aims to determine the possible risk factors associated with POST following oral and maxillofacial surgery to reduce POST occurrence, provide patients with more comfortable medical services, and improve patient satisfaction.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Patients with oral and maxillofacial surgery who underwent endotracheal intubation under general anesthesia in the Stomatology Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine between April 2020 and April 2021 were enrolled in the current retrospective research (n=908). Inclusion criteria: age between 4 and 80 years; in the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) I and II physical status; in need of oral and maxillofacial surgery; with preoperative case data and anesthesia record sheet; the patients were evaluated in the postoperative period for the duration of their hospital stay. Exclusion criteria: patients with obstructive respiratory disease (n=3); patients with severe systemic disease (n=2); patients with acute upper respiratory tract infection (n=5); patients with severe drug dependence and mental disorder (n=4); patients with acute pharyngitis (n=3). The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Stomatology Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine [No.2021-28(R)]. Written informed consent was waived due to the study’s retrospective design. All patients data were anonymized and maintained with confidentiality.

Data Collection

Data were obtained from patient’s hospitalization records, anesthesia records, postoperative follow-up records, and anesthesia quality control report forms. Information was collected on the factors that were thought to have influenced POST. Preoperative evaluation: gender, age, ASA, surgical site, and the presence or absence of throat and lung disease. Intraoperative evaluation: operative duration, catheter fixation types, cough during extubation, nasal intubation, difficult laryngeal exposure, use of non-steroidal analgesics, intubation frequency, cuff pressure, and catheter sliding distance. Postoperative evaluation: the presence or absence of sore throat was recorded during the first 24h after the operation.

Anesthesia Methods

After entering the operating room, various vital signs of patients were routinely monitored, including heart rate, respiration, non-invasive blood pressure, pulse oxygen saturation, etc. Peripheral venous access was opened. Anesthesia was induced by intravenous injection of propofol 1.5–2.5 mg/kg, fentanyl 2μg/kg, cis-atracurium 0.15mg/kg, remifentanil 1μg/kg and dexamethasone 0.1mg/kg. All intubations were performed by an anesthesiologist with at least 3 years of experience with a visual laryngoscope (UEscoPE, Zhejiang UE Medical Corp. China). The size of the blade was chosen based on the patient’s size and the anesthesiologist’s preference. Disposable PVC endotracheal tubes with high volume low-pressure cuffs were used for intubation. Immediately after intubation, the tracheal tube cuff was inflated with enough room air until no air leakage was audible. The endotracheal tube was fixed with adhesive tape, which could be divided into unilateral fixation and bilateral fixation. Unilateral fixation: the end of the adhesive tape is located at the same side of the endotracheal tube; Bilateral fixation: the end of the adhesive tape is located on the left and right sides of the endotracheal tube.

Anesthesia was maintained with remifentanil (0.1–0.2 μg/kg/min), nitrous oxide (40–50%), and sevoflurane (0.8–2%) at a minimum alveolar concentration value of 0.6–1.0, or with propofol (4–6mg/kg/h). Medication dosage was adjusted according to the change in vital signs, and the bispectral index (BIS) value was maintained between 40 and 60. At the end of the operation, anesthesia maintenance drugs were stopped, and cuff pressure was monitored. The endotracheal tube was removed when the patient showed stable vital signs and met the criteria of extubation. The patients were returned to the ward after complete resuscitation.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by SPSS software (version 23.0). Categorical variables were expressed as counts (percentages) and were analyzed by the chi-square test. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to check the distribution normality. Normally distributed continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD, and non-normally distributed continuous variables were represented as the median and quartile [M (P25, P75)]. The comparisons of continuous variables were made using the Mann–Whitney U-test based on the data distribution. Logistic regression analysis was adopted to identify the independent predictors for POST. Then, the independent predictors of POST in different age groups (4≤age≤14; 14<age≤60; age >60) were analyzed after adjusting for relevant covariates such as gender, ASA, throat and lung disease, nasal intubation, and so on by logistic regression analysis. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Based on the multivariate logistic regression analysis results, the independent predictors were included for logistic regression model construction. The random forest model was also constructed to compare the performance with the logistic regression model. The dataset was divided into 3 parts, 20% for testing, 70% for training, and 10% for validation. The performance of the model was evaluated using the AUC of ROC, accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and F1. In addition, the importance of each feature was calculated using sklearn.

Results

Population Characteristics

A total of 891 participants (483 males and 408 females) of which 153 cases had postoperative sore throat were finally enrolled in the study. The mean age of patients was 26.019±17.467 years. About 5.882% of cases had a cough during extubation in patients with POST compared with that 2.304% in those without POST with a significant difference (P <0.05). There were 87 females in the POST group and 321 females in the without POST group accounting for 56.863% and 43.496, respectively (P <0.05). Besides, the significant distribution of surgical sites between those with and without POST was observed (P <0.05). However, there were no significant differences in throat and lung disease, nasal intubation, difficult laryngeal exposure, use of non-steroidal analgesics, catheter fixation types, intubation frequency, ASA, cuff pressure, catheter sliding distance, operation duration, and age between two groups (all P >0.05) (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Characteristics of Patients Without or with POST |

In detail, the without POST group consists of 417 males (56.5%) and 321 females (43.5%). The POST group included 66 males (43.1%) and 87 females (56.9%). In the without POST group, the distribution of age, ASA, catheter fixation types, use of non-steroidal analgesics, throat and lung disease, nasal intubation, surgical sites, and operation time were significantly different from the male and female groups (all P <0.05). However, no significant gender-specific differences were evident for all covariates in the POST group (all P >0.05) (Table S1).

Cough During Extubation and Female Gender Independently Predicted POST

To investigate the risk factors associated with POST, univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed. Univariate analysis revealed that the cough during extubation and gender were significantly associated with POST (all P <0.05). Cough during extubation with an odds ratio (OR) of 2.983 and gender female (OR=1.833) were still independent predictors for POST (all P <0.05) (Table 2). These results indicated that a cough during extubation and female gender would increase the risk of POST occurrence.

|

Table 2 Association of POST Occurrence with Various Covariates Using Logistic Regression Analysis |

Further, we evaluated the value of cough during extubation and gender in predicting POST occurrence in different age groups. In the 4≤age≤14 and 14<age≤60 groups, the female gender was associated with an increased risk of POST occurrence (P <0.05). After adjusting ASA and throat and lung disease, the gender female was still significantly related to POST (P <0.05). After adjusting all the other covariates, the female gender could also independently predict POST occurrence (P <0.05). However, cough during extubation was an independent risk factor for POST after adjusting ASA and throat and lung disease (P <0.05), while was not significantly linked to POST occurrence after adjusting all the other covariates (P >0.05) (Table 3). The above findings suggested that cough during extubation and female gender might play an essential role in predicting POST occurrence.

|

Table 3 The Value of Cough During Extubation and Gender in Predicting POST Occurrence Stratified by Age |

Model Construction and Evaluation

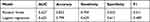

Subsequently, cough during extubation and gender were enrolled for the logistic regression model and random forest model for comparison. The results showed that the random forest presented a slightly stronger effect on predicting POST occurrence than the logistic regression model in terms of AUC. The AUCs for the random forest model and logistic regression model were 0.627 and 0.625, respectively (Figure 1A). The random forest model had an accuracy of 0.832, a sensitivity of 0.704, a specificity of 0.553, and an F1 of 0.311. The logistic regression model showed an accuracy of 0.799, a sensitivity of 0.629, a specificity of 0.611, and an F1 of 0.489 (Table 4).

|

Table 4 Machine Learning Algorithms and Accuracy in Predicting POST |

Further, we identified the variable that had a higher contribution to the model predictive power by sklearn. The importance weights were obtained for each variable. As shown in Figure 1B, gender had a higher importance weight than cough during extubation. These results revealed that the model containing gender and cough during extubation had a certain performance in predicting POST occurrence. Of note, gender exhibited a superior ability to cough during extubation.

Discussion

POST is a well-recognized complication after general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation.16 While it is generally considered as a minor side effect, POST is a leading undesirable postoperative outcome and negatively affects patient satisfaction and recovery.17 POST occurrence has been described in the literature in the context of various surgeries such as nasal surgery, lumbar or thoracic spine surgery, orthopedic lower extremity surgery, and total hip arthroplasty.18–22 However, there is a lack of research on the targeting factors related to POST in patients undergoing oral and maxillofacial surgeries with general anesthesia. Our study revealed female gender and cough during extubation as the independent predictors for POST occurrence in oral and maxillofacial surgery after general anesthesia.

In this study, POST occurred in 17.2% (153/891) of patients who underwent oral and maxillofacial surgeries under general anesthesia. A variety of factors have been identified to be associated with POST incidence. Hohlrieder et al reported that the use of a 7.5–8 mm endotracheal tube for men and 6.5–7 mm for women contributed to lower POST rates compared with larger sizes of the endotracheal tube.23 Besides, limiting cuff pressures might reduce POST occurrence.24 Decreased blood flow to the tracheal mucosa might cause ischemic damage ranging from minor irritation to tracheal stenosis when the cuff pressure is above 30 cm H2O.25,26 However, Phillip et al14 observed no significant correlation between cuff pressure and POST, which was similar to the result of our study. This indicated that POST is more likely to occur when several factors overlap. Interestingly, previous studies have well documented the presence of racial differences in the POST incidence. There is a study in Iran showed that POST occurred in 13.7% of all patients who received general anesthesia,27 while another study in the UK showed the incidence to be 63.9%.28 We found that there were significant distributions of cough during extubation, surgical sites, and gender in patients with/without POST. Logistic regression analysis results showed that cough during extubation and female gender could independently predict the POST occurrence. Of note, the female gender was an independent predictor for POST occurrence after adjusting all covariates in patients at 4≤age≤14 and 14<age≤60 groups. In those at age >60 years, cough during extubation was notably related to POST occurrence after adjusting ASA and throat and lung disease. By integrating the two independent predictors into model construction, we found that the model exhibited certain performance in predicting POST occurrence.

POST is thought to be caused by chronic inflammatory stimulation of the airway (device factors), leading to abrasion of the airway mucosa and the release of neurotransmitters.29 When men and women were exposed to the same pain stimulus, women assessed the level of pain more strongly.30 Additionally, women tended to have a lower pain tolerance threshold than men, suggesting that female gender was a factor influencing POST recognizing and expressing POST.31 Of note, anxiety and psychological stress would increase pain.32 Therefore, the authors speculated that preoperative emotional intervention for women might help reduce or alleviate POST occurrence. Dryness in the mouth and throat was more common in females compared to males, which might be an explanation for the female gender with higher POST incidence.33 Moreover, polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs) can be recruited to an inflammatory site by locally secreted pro-inflammatory cytokines during endotracheal intubation. These cytokines including IL-1β, TNF, and IL-8 may also delay PMN apoptosis, resulting in the production of more cytokines and chemokines to maintain local inflammation.34 Hence, it is reasonable to infer that the cough during extubation might lead to the initial stimulus for the inflammation, promoting POST.

Although we failed to obtain NRS scores to analyze the POST severity since participants in our study involved many children who might reflect inaccurate scores, this research explored the potential risk factors for POST and might provide guidance for the effective prevention of POST occurrence in oral and maxillofacial surgery.

In conclusion, female gender and cough during extubation were independent predictors for POST after oral and maxillofacial surgery with general anesthesia. Careful attention should be paid to these two aspects and effective preventive strategies should be taken against POST to improve clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction degree.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Stomatology Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine. Written informed consent was waived due to the study’s retrospective design. All patients data were anonymized and maintained with confidentiality.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Sumphaongern T. Risk factors for ala nasi pressure sores after general anesthesia with nasotracheal intubation. Heliyon. 2020;6(1):e03069. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e03069

2. Shen W, Cai X, Liu X, Zhang Z, Wang X, Yu A. Flexible bronchoscope versus video laryngoscope for orotracheal intubation during upper gastrointestinal endoscopic surgery in left lateral position: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Gen Med. 2022;15:6097–6104. doi:10.2147/IJGM.S366020

3. Lee WK, Kim MS, Kang SW, Kim S, Lee JR. Type of anaesthesia and patient quality of recovery: a randomized trial comparing propofol-remifentanil total i.v. anaesthesia with desflurane anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2015;114(4):663–668. doi:10.1093/bja/aeu405

4. Lone PA, Wani NA, Ain QU, Heer A, Devi R, Mahajan S. Common postoperative complications after general anesthesia in oral and maxillofacial surgery. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2021;12(2):206–210. doi:10.4103/njms.NJMS_66_20

5. Apipan B, Rummasak D, Wongsirichat N. Postoperative nausea and vomiting after general anesthesia for oral and maxillofacial surgery. J Dent Anesth Pain Med. 2016;16(4):273–281. doi:10.17245/jdapm.2016.16.4.273

6. Lin Y, Tiansheng S, Zhicheng Z, Xiaobin C, Fang L. Effects of ramosetron on nausea and vomiting following spinal surgery: a meta-analysis. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2022;96:100666. doi:10.1016/j.curtheres.2022.100666

7. Wang G, Qi Y, Wu L, Jiang G. Comparative efficacy of 6 topical pharmacological agents for preventive interventions of postoperative sore throat after tracheal intubation: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 2021;133(1):58–67. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000005521

8. Tanaka Y, Nakayama T, Nishimori M, Tsujimura Y, Kawaguchi M, Sato Y. Lidocaine for preventing postoperative sore throat. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(7):CD004081. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004081.pub3

9. Gupta D, Agrawal S, Sharma JP. Evaluation of preoperative Strepsils lozenges on incidence of postextubation cough and sore throat in smokers undergoing anesthesia with endotracheal intubation. Saudi J Anaesth. 2014;8(2):244–248. doi:10.4103/1658-354X.130737

10. P.s. L, Miskan MM, Y.z. C, Zaki RA. Staggering the dose of sugammadex lowers risks for severe emergence cough: a randomized control trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2017;17(1):137. doi:10.1186/s12871-017-0430-3

11. Singh NP, Makkar JK, Wourms V, Zorrilla-Vaca A, Cappellani RB, Singh PM. Role of topical magnesium in post-operative sore throat: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Indian J Anaesth. 2019;63(7):520–529. doi:10.4103/ija.IJA_856_18

12. Ki S, Myoung I, Cheong S, et al. Effect of dexamethasone gargle, intravenous dexamethasone, and their combination on postoperative sore throat: a randomized controlled trial. Anesth Pain Med. 2020;15(4):441–450. doi:10.17085/apm.20057

13. Ho M. The induction of interferons and related problems. Jpn J Exp Med. 1967;37(2):169–182.

14. Levin PD, Chrysostomos C, Ibarra CA, et al. Causes of sore throat after intubation: a prospective observational study of multiple anesthesia variables. Minerva Anestesiol. 2017;83(6):582–589. doi:10.23736/S0375-9393.17.11419-7

15. Inoue S, Abe R, Tanaka Y, Kawaguchi M. Tracheal intubation by trainees does not alter the incidence or duration of postoperative sore throat and hoarseness: a teaching hospital-based propensity score analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2015;115(3):463–469. doi:10.1093/bja/aev234

16. Kuriyama A, Maeda H, Sun R. Topical application of magnesium to prevent intubation-related sore throat in adult surgical patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Anaesth. 2019;66(9):1082–1094. doi:10.1007/s12630-019-01396-7

17. Gemechu BM, Gebremedhn EG, Melkie TB. Risk factors for postoperative throat pain after general anaesthesia with endotracheal intubation at the University of Gondar Teaching Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia, 2014. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;27:127. doi:10.11604/pamj.2017.27.127.10566

18. Yu JH, Paik HS, Ryu HG, Lee H. Effects of thermal softening of endotracheal tubes on postoperative sore throat: a randomized double-blinded trial. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2021;65(2):213–219. doi:10.1111/aas.13705

19. Yoon HK, Lee HC, Oh H, Jun K, Park HP. Postoperative sore throat and subglottic injury after McGrath(R) MAC videolaryngoscopic intubation with versus without a stylet in patients with a high Mallampati score: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2019;19(1):137. doi:10.1186/s12871-019-0811-x

20. Wang J, Chai B, Zhang Y, Zheng L, Geng P, Zhan L. Effect of postoperative ultrasound-guided internal superior laryngeal nerve block on sore throat after intubation of double-lumen bronchial tube: a randomized controlled double-blind trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2022;22(1):276. doi:10.1186/s12871-022-01819-x

21. Park JH, Lee YC, Lee J, Kim S, Kim HC. Influence of intraoperative sevoflurane or desflurane on postoperative sore throat: a prospective randomized study. J Anesth. 2019;33(2):209–215. doi:10.1007/s00540-018-2600-y

22. Huh H, Go DY, Cho JE, Park J, Lee J, Kim HC. Influence of two-handed jaw thrust during tracheal intubation on postoperative sore throat: a prospective randomised study. J Int Med Res. 2021;49(2):300060520961237. doi:10.1177/0300060520961237

23. Hohlrieder M, Brimacombe J, Eschertzhuber S, Ulmer H, Keller C. A study of airway management using the ProSeal LMA laryngeal mask airway compared with the tracheal tube on postoperative analgesia requirements following gynaecological laparoscopic surgery. Anaesthesia. 2007;62(9):913–918. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2007.05142.x

24. Maruyama K, Sakai H, Miyazawa H, et al. Sore throat and hoarseness after total intravenous anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2004;92(4):541–543. doi:10.1093/bja/aeh098

25. Dobrin P, Canfield T. Cuffed endotracheal tubes: mucosal pressures and tracheal wall blood flow. Am J Surg. 1977;133(5):562–568. doi:10.1016/0002-9610(77)90008-3

26. Grillo HC, Donahue DM, Mathisen DJ, Wain JC, Wright CD. Postintubation tracheal stenosis. Treatment and results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995;109(3):486–492;discussion 492–483. doi:10.1016/S0022-5223(95)70279-2

27. Ebneshahidi A, Mohseni M. Strepsils(R) tablets reduce sore throat and hoarseness after tracheal intubation. Anesth Analg. 2010;111(4):892–894. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181d00c60

28. Kloub R. Sore throat following tracheal intubation. Middle East J Anaesthesiol. 2001;16(1):29–40.

29. Mitobe Y, Yamaguchi Y, Baba Y, et al. A literature review of factors related to postoperative sore throat. J Clin Med Res. 2022;14(2):88–94. doi:10.14740/jocmr4665

30. Feine JS, Bushnell CM, Miron D, Duncan GH. Sex differences in the perception of noxious heat stimuli. Pain. 1991;44(3):255–262. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(91)90094-E

31. Lautenbacher S, Strian F. Sex differences in pain and thermal sensitivity: the role of body size. Percept Psychophys. 1991;50(2):179–183. doi:10.3758/BF03212218

32. Ali A, Altun D, Oguz BH, Ilhan M, Demircan F, Koltka K. The effect of preoperative anxiety on postoperative analgesia and anesthesia recovery in patients undergoing laparascopic cholecystectomy. J Anesth. 2014;28(2):222–227. doi:10.1007/s00540-013-1712-7

33. Kuo CFJ, Barman J, Liu SC. Quantitative measurement of adult human larynx post general anesthesia with intubation. Int J Med Sci. 2022;19(3):425–433. doi:10.7150/ijms.69425

34. Puyo CA, Dahms TE. Innate immunity mediating inflammation secondary to endotracheal intubation. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;138(9):854–858. doi:10.1001/archoto.2012.1746

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.