Back to Journals » Open Access Journal of Contraception » Volume 13

“I Got What I Came for”: A Qualitative Exploration into Family Planning Client Satisfaction in Dosso Region, Niger

Authors Calhoun LM , Maytan-Joneydi A, Nouhou AM, Benova L, Delvaux T , van den Akker T, Agali BI, Speizer IS

Received 23 February 2022

Accepted for publication 5 June 2022

Published 12 July 2022 Volume 2022:13 Pages 95—110

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/OAJC.S361895

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Igal Wolman

Lisa M Calhoun,1– 3 Amelia Maytan-Joneydi,1 Abdoul Moumouni Nouhou,4 Lenka Benova,3 Thérèse Delvaux,3 Thomas van den Akker,2,5 Balki Ibrahim Agali,4 Ilene S Speizer1,6

1Carolina Population Center, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA; 2Athena Institute, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, Netherlands; 3Department of Public Health, Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium; 4GRADE Africa, Niamey, Niger; 5Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, Netherlands; 6Department of Maternal and Child Health, Gillings School of Global Public Health, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Correspondence: Lisa M Calhoun, Carolina Population Center, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 123 West Franklin Street, Suite 210, Chapel Hill, NC, 27516, USA, Email [email protected]

Background: Client satisfaction is recognized as an important construct for evaluating health service provision, yet the field of family planning (FP) lacks a standard approach to its measurement. Further, little is known about satisfaction with FP services in Niger, the site of this study. This study aims to understand what features of FP visits were satisfactory or dissatisfactory from a woman’s perspective and reflect on the conceptualization and measurement of satisfaction with FP services.

Methods: Between February and March 2020, 2720 FP clients (ages 15– 49) were interviewed across 45 public health centers in Dosso region, Niger using a structured survey tool. The focus of this paper is on a random sub-sample of 100 clients who were additionally asked four open-ended questions regarding what they liked and disliked about their FP visit. Responses were audio-recorded, translated into French, transcribed, translated into English, coded, and analyzed thematically.

Results: FP clients described nine key visit attributes related to their satisfaction with the visit: treatment by the provider, content of the counseling, wait time, FP commodity availability, privacy, cleanliness/infrastructure, visit processes and procedures, cost, and opening hours. The reason for FP visit (start, continue, or change method) was an important driver of the dimensions which contributed to satisfaction. Pre-formed expectations about the visit played a critical role in shaping satisfaction, particularly if the client’s pre-visit expectations (or negative expectations) were met or not and if she obtained what she came for.

Conclusion: This study makes a significant contribution by identifying visit attributes that are important to FP clients in Dosso region, Niger, and highlights that satisfaction with FP services is shaped by more than just what occurs on the day of service. We propose a conceptual framework to understand satisfaction with FP services that can be used for future FP programming in Niger.

Keywords: client satisfaction, family planning, contraception, Niger

Introduction

Patient satisfaction is a multi-dimensional, subjective, client-centered concept that has long been recognized globally as an important indication of a health system’s success in responding to and meeting its clientele’s values and expectations.1,2 Including patient perspectives is important as satisfied patients are more likely to return for services and speak favorably about the services they received, thereby increasing utilization of services.3–6 Patient satisfaction has been used as a metric to evaluate service provision, and is thought to provide insights into patients’ future health service behaviors and choices.2,7–9 Patient satisfaction is believed to be the result of provision of high-quality services.1,2,4 Despite interest in patient satisfaction across disciplines, contexts, and over time, there is no consensus on the conceptualization and measurement of satisfaction.9–13 The term “patient”, “user”, and “client” have often been used synonymously in the literature on satisfaction due to its study in different disciplines; in this paper, which focuses on family planning (FP) service utilization, we use the term “clients.”

Judith Bruce’s quality of care framework (1990) laid a foundation for how the global community measures quality of family planning services.14 She identified six key components of quality care including choice of method, provision of accessible and accurate information, technical competence of providers, interpersonal relations, follow up and continuity mechanisms, and appropriate consultation of services that are responsive to each person’s needs. In the more than 30 years that have followed the development of the Bruce framework, many others have contributed to the refinement of the measurement of quality of care in family planning services.14–17 Proposed revisions include the need for new metrics to measure quality at the service delivery point level, based on service processes, and from a client focus (eg, client-centered measures). In this last category, client satisfaction has emerged as an important area to address with the goal of supporting improved service use and health outcomes.

Within the FP field, it is often assumed that client satisfaction is the outcome of high-quality services;14,15 however, these are separate cognitive constructs that may not be directly related.9 Provision of high-quality services does not necessarily guarantee a client is satisfied with their facility visit and clients who report being satisfied with their visit have not necessarily received high quality services.9 New client-centered measures for quality of care have been proposed based on qualitative and quantitative data, but less research has been done to assess satisfaction from a client perspective.17–19 Conceptual models of satisfaction with reproductive health services developed using data from high-income (HIC) and low-and middle- income countries (LMIC) emphasize the role that pre-visit expectations, service accessibility, and perceived service quality play in influencing satisfaction.8,9

To date, client satisfaction lacks a validated, universally accepted measurement approach.11–13 Examples from the FP literature from LMICs include questions in which clients are asked to express their opinion about the services received in terms of overall satisfaction or satisfaction with specific visit attributes; at times, this information has been used to create a satisfaction score.4,7,20–25 A challenge with this measurement approach is that there is often little variability in responses which may result from courtesy bias, having low expectations with services, or being pleased that they received any service.4,10,16,20,26,27 Despite quantitative studies reporting high satisfaction levels, qualitative studies provide a more nuanced perspective with lower levels of reported quality and satisfaction including reports of poor interpersonal relations with the provider, little privacy, and challenges with communication with the provider.26–29 This points to the need to qualitatively explore client satisfaction using an approach that considers which elements of the service encounter are important to FP clients and why.

In the Republic of Niger, the site of this study, the total fertility rate was 7.6 children per woman in 2012.30 Modern contraceptive use among married women has increased from 5.0% in 2006 to 18.1% in 2017.30,31 Unmet need for limiting among married women remained low at 2.4% but need for spacing was 18.6% in 2017,31 putting women at risk of unintended pregnancy. To respond to couples’ reproductive health needs, the Government of Niger developed a strategy to broaden method choice through delivery of a minimum service package.32 Research from West and Central Africa shows that contraceptive use is low in this region for a multitude of factors, including the desire for large families, opposition to use, fear of side effects, and limited access to FP services.33–35

Client satisfaction with FP services in Niger is understudied. A 1992 study by Cotten et al36 explored reasons for early contraceptive discontinuation in Niamey, finding that over 90% of female FP clients were satisfied with services and felt treated respectfully. However, 21% of respondents felt that the waiting time was too long.36 Similarly, a study to compare measurement approaches of satisfaction was undertaken in 1997–1998 in the Tahoua region and found that 90% of female and male clients interviewed using a three-point Likert scale were “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with the FP services, but only 55% of those who participated in a focus group reported the same.28 A more recent study assessed the relationship between use of a counseling tool and client satisfaction and found that about one-third of clients who were exposed to the counseling tool and one-quarter of those not exposed reported that they were very satisfied with their FP visit.37 To the best of our knowledge, only one qualitative study was undertaken in Niger to explore client satisfaction with FP services, and none in the last 20 years.28

This study explores how female clients describe satisfaction with FP services in Niger. Additionally, this study allows us to reflect on conceptual and measurement approaches to satisfaction with FP services and to develop a conceptual framework for satisfaction with FP services in Niger. The conceptual framework provides insights on how measurement approaches can be modified to fully capture the client experience and integrate it into improvement of FP service provision in Niger and elsewhere in the region.

Methods

Study Design

This study was part of a larger cross-sectional quantitative assessment conducted in Niger between February and March 2020. The program activities, led by Pathfinder International, included the implementation of a counseling tool to segment clients that would subsequently allow providers to offer targeted counseling based on each client’s responses to questions about their knowledge and beliefs about FP. The primary goal of the assessment was to determine if clients who were segmented using the counseling tool reported higher quality of services and were more satisfied with the services that they received than clients who were not segmented. The study design and findings from the assessment were previously published.37

We conducted a qualitative study nested within the quantitative assessment among female exit interview clients at a subset of the public health facilities included in the parent study. This paper is focused on the qualitative component which consisted of open-ended questions administered following the completion of a structured exit-interview questionnaire to explore which features of the facility visit were satisfactory or dissatisfactory to women. Selected quantitative data from the structured questionnaire were triangulated with qualitative data to contextualize the findings.

Context

The study was conducted in the Dosso region in southwest Niger which borders Nigeria and Benin. Dosso is a predominantly rural area, with only 10% of the estimated 2.5 million people residing in urban areas.38

The health system in Niger includes both public and private sectors and is organized in a three-level pyramidal structure.39 The first level of the public system includes public health centers (Centre de Santé Intégré – CSI) and public health posts, which focus on provision of primary health care.39 CSI are typically staffed by nurses and are generally meant to serve a catchment area of 5000–15,000 people.39,40 As of 2017, there were 137 CSIs in Dosso region, the tier of which is the focus of this paper.38

In 2017, the most used methods in Niger were pills, injectables, and implants, with oral pills and injectables each comprising more than one-third of the modern method mix.31 Nationally, 85.3% of modern method users obtained their method from the public sector and more specifically, 60.6% from a CSI.30 Contraception is available free of charge in the public sector.

Population and Study Procedures

Quantitative Data

The assessment utilized a quasi-experimental design with three arms that varied based on implementation of program activities by Pathfinder International, including the timing of rollout of the segmentation tool. The assessment included 15 CSI per arm for a total of 45 CSI. It was not possible to randomize CSIs by arm because there were 15 CSI in Arm 1 that had been implementing the segmentation counseling tool since 2017 as part of a larger demand generation project led by Pathfinder International. The CSIs in Arms 2 and 3 were selected from a list of 40 CSIs in the region that were not implementing the demand generation activities. Arm 2 included a sample of 15 CSIs where implementation of the segmentation counseling tool began in October 2019. Arm 3 included 15 CSIs with no implementation of the segmentation counseling tool or the demand generation activities.

During a two-month period, one or two interviewers were assigned to each of the 45 CSIs with the task of interviewing all FP clients. All exiting clients were approached to ascertain if they met the eligibility criteria for participation in the study (seeking FP services and ages 15–49 years). Upon receiving informed consent, interviews were conducted in a private setting in or around the CSI and took about 35 minutes to complete. The structured survey was administered through a face-to-face interview in the local language with a trained interviewer. In total, 2720 exit clients completed the structured interview.

Qualitative Data

Upon completing the structured questionnaire, a separate informed consent was sought to participate in the qualitative component consisting of open-ended questions. To this end, three interviewers were trained to administer a set of four open-ended, qualitative questions. The interviewers were intended to remain at the same three CSI during the entire data collection period and ask all the FP exit clients the open-ended questions. However, due to low client volume in selected CSI, the three interviewers were moved halfway through data collection to three different CSI with higher client volume. Therefore, the data from the open-ended questions were collected from all FP exit clients at six CSIs (two in each study arm). In total, 101 exit clients completed the qualitative questionnaire. All responses to the qualitative questions were digitally voice recorded.

Data Collection Instrument

Quantitative Data

The structured questionnaire included demographic questions and an extensive list of questions about the reason for visit, FP services received, quality and content of counseling, individual preferences and needs, and satisfaction with the visit.

Qualitative Data

Open-ended questions were developed for this study to explore what women liked and disliked about their FP visit; specifically the clients were asked:

- What did you like about your interaction with your family planning provider today? Why?

- What did you dislike about your interaction with your family planning provider today? Why?

- What did you like about your experience seeking FP services at this public health center (CSI)? Why?

- What did you dislike about your experience seeking FP services at this public health center (CSI)? Why?

Interviewers were trained to probe for more details about what the respondent said and what could have been done to improve the client’s experience.

Data Analysis

Quantitative Data

To ascertain information about demographic characteristics of the clients who responded to the open-ended questions, a dataset was created from the structured questionnaire. The dataset included age, marital status, education, method use upon visit completion, and client type (eg, new user, resupply client, restart clients, and other FP-related reasons). This information was used alongside the qualitative data to explore themes, connections and trends about satisfaction by client type, method type, and demographic characteristics. Descriptive analyses including frequencies and proportions were conducted for a small number of quantitative variables.

Qualitative Data

Applied thematic analysis was used to analyze the qualitative data on client satisfaction.41 The audio-recorded, open-ended responses were translated from Zarma or Hausa into French and then transcribed in French. French transcripts were later translated into English. A codebook was developed based on a priori, structural codes; these codes were developed from the guide and from existing measures of client satisfaction, including the measures of satisfaction in the Quick Investigation of Quality20 and the Service Provision Assessment (SPA).42 Structural codes included: wait time, duration of appointment, facility opening hours and days, treatment by the provider and staff, cost for services, auditory and visual privacy, availability of commodities, counseling and examination, and facility cleanliness.

Two researchers read the transcripts and coded the transcripts to segment the text on the components of client satisfaction based on structural and emergent content themes. Inter-coder reliability was assessed throughout the coding process, to ensure a common understanding of the codebook and consistent application of codes. Approximately 10% of transcripts were double-coded to assess reliability; discrepancies were discussed and resolved. Next, an Excel matrix was created, and coding reports were generated. A third researcher reviewed the code reports and the Excel matrix to identify emerging content themes, and connections between elements of satisfaction. Content codes were developed through an iterative process of identifying and defining new themes as they emerged in the data. New content codes were then applied to all transcripts. Once the content coding and modified matrix was complete, one of the original researchers reviewed them to verify each theme. The two researchers discussed and resolved any discrepancies in the interpretation. Any ambiguities in the final translations were cross-checked with the translators to ensure correct understanding of the quotes.

Ethics Approval

Approval for the study protocol, informed consent procedures and materials, and survey tools was provided by the Niger Comité National d’Ethique pour la Recherche en Santé (CNERS) and by the Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (Number: 19–3042).

Results

In total, 101 women answered the qualitative questions (ranging from 11 to 34 in each of the six CSIs) following the structured exit interview. Due to the focus on clients whose primary reason for facility visit was FP, one respondent was dropped from the analysis because she was at the facility for childbirth. Therefore, the final number of respondents included in this analysis is 100, all of whom were female.

Description of the Sample

Table 1 presents the number of women by background characteristics and reason for their FP visit. Most women (n=57) were continuing FP clients who were at the facility to receive a resupply or refill of their current method. Approximately one-quarter of clients were at the facility to start a FP method for the first time (n=23); these clients are referred to as “new users”. Thirteen percent of the sample were women who had used a FP method previously, were not using at the time of visit, and were at the facility to restart a method (n=13). In addition, a small number of women were at the facility for other reasons: to switch methods (n=3), have their implant removed (n=3), and one woman who was experiencing problems with her implant. There were a similar number of women aged 15–24 and 25–39; these age groups comprise the majority (88%) of clients. Most women (63%) had no exposure to formal education. All women were ever married, and one woman was divorced. The majority (95%) of respondents were using any contraceptive method at the end of their visit: injectables (n=58), oral pills (n=29) and implants (n=8). A small number of women (n=5) left the facility without a method, though three of these women visited the facility intending to have their implant removed.

|

Table 1 Qualitative Sample of Women Using FP Services by Background Characteristics and Reason for FP Visit in 6 Public Health Centers in Dosso Region, Niger |

Visit Experience

Table 2 presents the visit attributes mentioned by women by reason for FP visit ranked from most to least salient. About three-quarters of respondents (74%) mentioned the importance of treatment by the provider. The content of counseling was mentioned by nearly half of respondents while about two-fifths mentioned wait time. For each attribute, differences by reason for FP visit are described. Analyses by other client characteristics did not produce any notable findings and therefore are not shown.

|

Table 2 Reported Visit Experience Attributes Among a Qualitative Sample of Women Using FP Services, by Reasons for FP Visit and Salience in Dosso Region, Niger |

Treatment by the Provider

Three main themes were identified from the respondents’ responses when discussing how they were treated by the provider: the provider’s use of customary greetings, general demeanor and conduct, and concerns about mistreatment. Often one of the first things respondents mentioned was the importance of being greeted warmly and respectfully by the providers. Respondents used words such as “courteous”, “calm”, and “warm” and often mentioned the importance of providers “having a smile on their face”. Respondents often went on to discuss varying aspects of their interaction with the provider, with some appreciating a familiarity or closeness with the provider. A 27-year-old woman who was at the facility to initiate use of the injectable reflected on her interaction with the provider as follows:

What I appreciated, he greets people well. He does his job well. He does not get mad. If you come quickly, he does it for you and you return home to tend to your responsibilities. Also, if the person comes to him, he speaks with people. He jokes with the person. He explains things well.

Additionally, as indicated by the above quote, many women expressed their satisfaction with their visit by saying that they were pleased they were not shouted at or treated poorly. This was true across all client types, but resupply clients more often expressed concerns about mistreatment, often juxtaposing it with the positive way in which they were treated during their visit. Several women cited previous visits where they had been shouted at for various things, such as coming outside of FP service opening hours, coming to the facility after having missed their original re-injection or re-supply (for pills) date, or not understanding the information they were given. Women reported prior experiences of being “shouted at”, “scolded”, and providers being “angry” or “upset”.

Content of the Counseling

Across all client types, about half of respondents mentioned some aspect of counseling during their interaction with the provider. When describing their interaction with providers, the most common topics mentioned were those related to method selection. Women were pleased that providers began their visit by asking them the reason for their visit rather than making assumptions; this approach made women more comfortable and encouraged open dialogue. This was particularly important for resupply clients, who were there to receive the same contraceptive method they were already using. Combined with being asked what they were there for, women then commonly expressed satisfaction with being able to choose which method they wanted. A 22-year-old oral pill resupply client said:

Me, it’s their work that I appreciate. When a person comes, they ask them the reason for their presence, after that, she chooses the method she wants. I really appreciated the contraceptive that I chose. That is what really pleased me.

Relatedly, women often stated that they were pleased that they were provided with information on different FP methods which enabled them to make their own choice. A 29-year-old woman at the facility to receive her next injection said:

What pleased me was mostly the presentation she gave me on the different contraceptive products, all the while asking me what I want.

Being told about different FP methods was important to all women, regardless of their reason for the visit. New users seemed overwhelmingly satisfied when they received information on several different FP methods. Resupply clients frequently referred to previous visits where they received information on different methods, and voiced appreciation for having received that information. A few resupply clients mentioned that they would have liked to receive information on different methods. A 25-year-old woman at the facility to receive her next injection shared:

And also what I did not appreciate is the fact that Madame gave me the shot standing without asking me anything. She did not even try to explain to me the methods and others. She said nothing to me. She just gave me the shot.

Yet, conversely, some resupply clients were pleased that the consultation was brief, with limited exchange of information. Two resupply clients specifically said they were pleased that they did “not chat with the provider”. These examples highlight that even among resupply clients, there are varying needs.

Waiting Time

One of the most common attributes of a positive FP encounter was short waiting time or being seen quickly by the provider. Fewer new users expressed concerns about waiting time compared to resupply and restart clients. In general, there was a mix of women stating that the wait time was acceptable and women who expressed extreme dissatisfaction with the wait time. A 32-year-old new implant user said:

I had the work very quickly. He received me well. He was open towards me. I hear people who say that if they come they wait before having the work. But me, really it is not the case.

Women who experienced long wait times expressed dissatisfaction and often mentioned being “thirsty”, “tired”, or most commonly, needing to take care of other responsibilities at home. A 20-year-old new user of the injectable said:

I waited a lot for the provider. I stayed until I was tired. The provider always comes late. Really, this is what I did not appreciate. Sometimes there are people who have a lot of concerns at home. They want to finish quickly and go back. Really, the wait is not good. It discourages a person.

Availability of FP Commodities

About one-third of women across all client types mentioned concerns about availability of commodities and supplies. It appears that all these respondents were referring to previous experiences when medications or supplies (such as syringes) were not available, and at times, they were referring to stockouts of medications not specific to FP. No client reported a stockout on the day of her interview. Previous experience of stockouts seemed essential in creating expectations for the FP visit. A 21-year-old woman at the facility to restart the injectable said:

What made me happy is the fact of reaching the objective of my visit. When they have stockouts of syringes they cannot administer the injection so they give pills and say to take them until they receive syringes.

Auditory and Visual Privacy

Privacy was mentioned by most client types, with nearly half of restart clients mentioning privacy as an issue yet less frequent mention by resupply or new users; the responses given by women were not of enough depth to understand potential reasons for these differences. Both auditory and visual privacy were mentioned, often together. Several respondents mentioned that they appreciated having a dedicated room for FP where clients could not be seen or heard. A 21-year-old woman restarting the injectable said:

It’s a really nice setting because it is in a room and the door is closed so no one can hear what you say. No one sees us.

Cleanliness and Infrastructure

Some women discussed how pleased they were with the physical infrastructure at the facility and its cleanliness. Women spoke positively about the examination rooms, including the presence and quality of furniture and examination beds. A few women highlighted that the courtyard at the facilities were spacious with ample availability of shade. Finally, a small number of women discussed hygiene, both how the providers followed protocols by washing hands and that the health facility was “very clean to the point that even if food falls on the ground, you could pick it up and eat it” (25-year-old injectable resupply client).

Visit Processes and Procedures

Women also reflected on several components related to the check-in process and staffing. Overall, women seemed genuinely pleased when things ran efficiently and yet, experienced FP clients critiqued aspects of the check-in process and staffing which they believed should be addressed to reduce wait time. Several resupply clients who expressed frustration with wait time suggested that facilities may need to change their staffing plans, either by increasing the number of staff or shifting other staff members to provide FP. Additionally, several women were pleased when there was an established procedure for ensuring women were seen in the order they arrived and women expressed dissatisfaction when that procedure was not followed; this was only mentioned by resupply clients. A satisfied 26-year-old woman at the facility to resupply her oral pills said:

Also, I appreciated the order of moving up in line to get the FP. Everyone respected the line. One by one to go into the office. Otherwise, it is a mess who will go next. Everyone hurries to have the work and to return home to do other work. Always there is a lot of women who come here to get FP.

A small number of respondents criticized the procedure for obtaining a health booklet (new clients) and the requirement to bring this booklet at return visits. One facility required that new clients arrive early and queue to receive the health booklet and then wait in another line to see the provider. Relatedly, a resupply client mentioned that her neighbor came to the facility to get FP but could not do so because there were no health booklets.

Cost

FP methods in Nigerien public health facilities are dispensed free of charge; a component appreciated by clients “Truly, I am happy. …. The fact that I found the pill and they gave it to me for free. I did not give a single franc” (27-year-old new user of oral pills).

Hence, cost was infrequently mentioned and raised only as an issue when supplies were not available, forcing women to purchase commodities or supplies in the private sector. This issue was only mentioned by resupply clients. As with stock outs, no clients reported paying for commodities or supplies during the visit but rather reflected on previous facility visits for FP or other services. A 30-year-old oral pill resupply client said:

R: … sometimes people confront that problem [stock out]. We go to the pharmacy and get the product and bring it back so we can be shown how to use it, whether it is injectable or pill.

I: In this case, what do you think should be improved?

R: It is to augment the stock because where there is a stock out, it is not very appealing. It is not appealing because when the person comes and it coincides with a rupture [in stock] and she doesn’t have money to go to the pharmacy to pay, what is she going to do?

Opening Hours

Several women mentioned they had to come early in the morning to receive FP services. This was closely related to comments about wait time and processes at the facility. A small number of women mentioned that they wished services were offered in the evening as a reason to maintain privacy and to accommodate their schedules better.

Overall Assessment of the Visit

In addition to the elements of visit experiences, women often provided responses that reflected on the visit overall. Two main themes were identified: whether they received what they came for and how the visit aligned with their expectations.

Across all client types, the most common answer about what pleased women was that they “got what they wanted” or “received what they came to get”. Seventy-seven women said they were either pleased because they got what they wanted or displeased because they did not. It was frequently the first thing women said when asked to share their experience. Women often stated it simply and directly, and linked it to receiving the specific method they wanted. Additionally, new users said they were satisfied because they received FP and discussed how FP is beneficial to plan and manage their lives and ensure that they raise healthy children.

Infrequently, women expressed dissatisfaction when they did not receive what they came for. A 21-year-old injectable resupply client expressed dissatisfaction with her visit when she missed her appointment date and the provider switched her to pills due to concerns about pregnancy. She said:

R: I came to get Depo they did not give it to me, they gave me pills, that is what I did not like.

I: Why then do you say that you do not like?

R: Because they did not give me what I came to get.

Women made statements in which they contrasted the overall success of the visit (received the services that they desired) against some of the negative components of their visit, such as a long wait time, a hurried consultation or a lack of privacy. This may be because many had a pre-formed expectation that there was a possibility that they would not be seen by the provider or not receive a method due to things that they had previously experienced or had heard from others. The expectation about why they may not be able to receive a contraceptive method or their method of choice was stated by a 20 year old client as follows:

R: What I really appreciated was the fact that I got what I came to get. I am really satisfied.

I: Why do you say you are satisfied with the services?

R: Because before if a woman comes sometimes they tell her that there are no medications. Or the provider is not here.

I: So if I understand well, there are times when there have been stock outs of medications at the level of the CSI [the health center]?

R: Yes, yes, even last year I came to get the medication and they told me there wasn’t any. It’s finished. It is only the shot that is left. As I do not want the shot I did not come back until today.

Throughout the interviews, expectations played a clear role in how the respondent gauged her visit and ultimately her opinion of the services she received. Expectations were often based on previous experiences, sometimes for FP, and sometimes for other health services. They were also based on stories that they had heard from others. Additionally, women also often compared services at one facility to another, or one provider to another, thus stating why the services that they received were better or worse than that. More specifically, some women anticipated being treated poorly and this was particularly an issue among resupply clients who were late for their appointment. Others expected stock outs of commodities or supplies and needing to change methods and long wait times.

Ultimately, some clients indicated that they were empowered and knowledgeable users of FP services, as evidenced by the following quote by a 37-year-old client at the facility to restart oral pills:

We maintain very good relations with them [the FP providers]. They address us politely. They calmly explain things to us, sometimes they make us laugh. They give us the opportunity to ask questions ….Among them, there are some that do not address us in the same way, but we know how to follow them calmly. If we do not feel good coming here we would not come.

Overall Client Satisfaction

The outcome of the woman’s assessment of the visit was the final determination as to if she was satisfied or not. Overwhelmingly, based on the qualitative responses, most women appeared to be satisfied with their visit. The reasons given by less satisfied clients were not homogeneous: one woman wanted her implant removed but was not able to do so, one woman was forced to switch methods, two women felt that the provider did not give enough information, and one woman was treated poorly and felt the wait was too long.

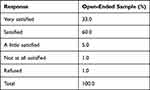

This is also supported by the quantitative data, which shows that greater than 90% of respondents were “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with their visit (Table 3). Importantly, the quantitative data show that clients were satisfied with their visit overall but masks the detailed information about what components of the visit could have gone better and why.

|

Table 3 Satisfaction with FP Visit Among Women Using FP Services Based on 4-Point Likert Scale as Captured in the Quantitative Exit Interview Tool, Dosso Region, Niger (n=100) |

Conceptual Framework

The conceptual framework in Figure 1 provides an overview of the identified thematic constructs and presents their relationship to client satisfaction with FP services. This model is based on the themes and constructs identified in the data and is adapted from a holistic model of satisfaction with healthcare10 and models of satisfaction with reproductive health services.8,9 A key underpinning of this conceptual framework is that satisfaction is influenced by a multitude of factors related to client characteristics, visit experience, and assessment of the visit. Our model differs from previously identified models because it considers the salience and role of specific visit features and recognizes the importance of receiving the specific services the woman came to the facility to obtain.

|

Figure 1 Conceptual framework for client satisfaction. Notes: Developed based on Niger findings and with insights from other frameworks that examine satisfaction of reproductive health services. Data from Alden et al,8 Murphy and Chakraborty,9 and Crow et al.10 |

Client characteristics describe the individual seeking FP services, such as the type of client, sociodemographic characteristics, their personal experiences and values, beliefs and expectations for service that are unique to the client. The visit experience encompasses all aspects of care on the day of visit, including aspects related to the client-provider interaction, processes at the facility and facility structure. The assessment of the visit is a key component of this model, whereby the client reflects on her visit experience relative to her expectations for care. Based on how she evaluates the visit, she reacts subjectively and expresses her level of satisfaction with the visit. This model includes a feedback loop from level of satisfaction to client characteristics; this is where new expectations form, including through the exchange of information with others. Overall, this conceptual framework highlights the dynamic nature of client satisfaction and how experiences with the health system build on one another.

Discussion

In this article, we explored the factors that influence FP clients’ satisfaction with services in Dosso region, Niger using open-ended questions among female exit interview clients aged 15–49. Our study highlights the dynamic, multifactorial processes through which clients are ultimately satisfied or dissatisfied with the services they receive. Clients mentioned several attributes related to the client experience on the day of visit as being important; treatment by the provider, counseling, and wait time were the most mentioned visit attributes. Clients’ experiences differed by client type, with returning clients frequently referring to their experience at previous visits. These earlier experiences often shaped the frequency and depth in which they discussed visit attributes and what they liked or disliked. At the core of satisfaction is the role that pre-formed expectations play in shaping satisfaction on the day of visit. This relates to whether expectations are positively or negatively met. Ultimately, the outcome of the visit, that is whether the client receives what she came for, is what we find is the most influential on satisfaction as reported upon facility exit.

Many clients in our study had previous exposure to the health facility, either for FP services, maternal health services, or otherwise. Throughout the interviews, it was clear that clients often referred back to previous experiences and that those experiences shaped their expectations for service. At times this manifested negatively, with clients expressing fears about being treated poorly or there being stock outs of FP commodities. Yet, most clients seemed satisfied and there was limited reporting of negative experiences at the current visit. Despite the established relationship between expectations and whether or not they are met being related to client satisfaction in healthcare literature,7,43 this relationship is infrequently discussed in the FP literature. Quantitative studies have described associations between older age, higher education, more experience with family planning, and higher parity with the level of satisfaction.21,25,44–46 These studies explain the findings by suggesting that respondents with these characteristics have higher expectations for care and therefore their level of satisfaction is tied to whether and how these expectations are met.21,25,44–46 In our study, women generally had low expectations of services, beyond the expectation that they may or may not obtain a FP method. Women were often satisfied when they received the FP method they wanted and were treated well by the provider. Conversely, they were dissatisfied if they did not get a method. These findings highlight the need to ensure consistent delivery of high quality, client-centered care, as satisfied clients are more likely to return for care and continue method use.3–6

Our findings highlight that the visit attributes identified by clients overlap and align with the client satisfaction questions typically asked in large-scale surveys, such as the Service Provision Assessment (SPA), as well as some of the other quality of care questions from recent studies focused on client-centered care.17,18,47 More specifically, respondents in our survey identified wait time, audio and visual privacy, commodity availability, facility operating hours, cleanliness of the facility, treatment by staff, and the cost for services. Despite the overlap, there were differences between the visit attributes measured in prior studies and those mentioned by clients in this study. A notable departure was that clients in our study did not mention the number of days services are available or provide much detail regarding the quality of the examination received. Conversely, respondents in our sample did discuss the treatment by providers as an important component that studies on quality often overlook; this has been raised as an important part of client-centered care.17,19,29 Our study also identified a factor that, to the best of our knowledge, is not routinely captured in quality or satisfaction studies: if there are organized, easily understood, and fair processes for check-in. By using qualitative data, our study also provided significant depth on the importance of different visit attributes and nuances within them that could inform future quantitative studies. For example, future quantitative studies should consider including a question on the provider’s use of customary greetings and/or in-depth questions about how the provider treated the client in one-on-one interactions to better assess satisfaction with treatment by the provider.

Additionally, our findings emphasize differences by client type and recognize that women may have different expectations and needs depending on their reason for visit. Thus, it is important to consider improved strategies to measure satisfaction that permit this variability by client characteristics; recent studies on client-centered care and contraceptive autonomy have begun to make the necessary modifications to measurement.17,19 For instance, a resupply client who desires a short visit with little to no counseling can say that she did not have a problem with any aspects of her interaction with the provider. Conversely, a new client may feel differently about her visit based on the level of interaction with the provider and amount of information provided. Our findings emphasize the importance of considering subjective questions as well as distinct questions by reason for the visit to better assess satisfaction (and quality).

Clients in our sample also had ideas and proposed approaches on how to improve services. Women expressed frustration about the processes at facilities, such as the check-in process or how women were supposed to queue. Clients may be treated as naïve users of the health system, yet they are experienced consumers and have knowledge and experience that should be considered to improve services at health facilities. Future work could include social accountability methods, such as community scorecards or developing complaint mechanisms, to help inform quality improvement measures at health facilities48 which could improve expectations and satisfaction.

The important features of the visit identified by clients in our study overlap with the little research that has been carried out on client satisfaction in Niger. A quantitative study by Cotten et al showed high levels of client satisfaction overall.36 Our study confirms the finding that most clients were satisfied with their visit. Similarly, the importance of respectful treatment by the provider as well as wait time were also found to be important.36 Despite a near 30-year gap between the study by Cotten et al and our study, some of the same visit attributes emerge as important to clients.

This study has several strengths and limitations. First, by asking clients open-ended questions about their satisfaction we were able to go beyond the standard quantitative measures of satisfaction and understand important details and connections across various themes. Few studies have qualitatively explored satisfaction with FP services, and to the best of our knowledge, this is the first peer-reviewed study to do so in Niger. Additionally, because the open-ended questions were added to a structured questionnaire, we were able to investigate how these same clients responded to a Likert question on satisfaction.

Despite the strengths of our study, there are some limitations worth noting. The open-ended, qualitative questions were added to the end of a structured questionnaire. Exit clients often have endured a long wait at the facility and are often in a hurry to leave the facility. This may result in clients rushing through the open questions or not answering fully. In addition, the structured questionnaire included measures related to quality of care and satisfaction; placing the open-ended responses after the structured questions may have resulted in biased responses about what components of the service were important. Additionally, our results may be subject to courtesy bias. Clients may report more positive experiences because they believe it is the correct or appropriate response. Some of the clients may have believed that study staff were also government facility staff, and this may have further contributed to courtesy bias. Additionally, clients may not accurately recall what took place during their visit. Finally, this study was conducted in some health centers where the segmentation intervention was being implemented. Some of the activities, such as recent training of providers, may have influenced our results.

Conclusion

This study makes an important contribution by identifying visit attributes which are important to FP clients in Dosso region, Niger and highlights that satisfaction on the day of service is shaped by factors that precede the visit. The findings about how expectations for mistreatment, unavailability of methods or inability to receive their method of choice due to missed appointments warrant program consideration given that these expectations arise based on past facility visits or information discussed in the community. Further study is needed about how experiences at FP visits are shared back in the community and if this influences women’s decisions to seek care for FP as well as where to seek care. To address concerns about mistreatment by providers, one of the most common things mentioned in our study, providers should attend regular training about provision of respectful care and the importance of adhering to customary norms for greeting and interaction with clients. The lessons from this and the related framework can be utilized to develop programs which emphasize improving the client experience based on the most salient visit features, particularly treatment by the provider. Though the findings and framework developed in this study are specific to the Nigerien FP context, they raise important considerations for how clients’ perceptions of their visit influence expectations for services and future care seeking behaviors beyond just the Niger context. Future work should explore the application of this framework in the Sahel region and beyond in order to determine its utility for informing programs in these contexts.

This study fills a gap in knowledge by providing information on a little studied topic in Niger in the context of a country with increasing contraceptive use. Addressing supply-side factors that may impede contraceptive use, including the expectation that clients may not get what they came to seek, is critical for women to have access to the FP method of their choice and for the well-being of women and children.

Abbreviations

CSI, Centre de Santé Intégré; FP, family planning; HIC, high income countries; LMIC, low- and middle-income countries; SPA, Service Provision Assessment.

Data Sharing Statement

Information about the study, survey tools and data are available at: https://dataverse.unc.edu/dataverse/fafc. A formal request needs to be made and a data sharing agreement will have to be made before sharing the data.

Ethics Approval

All study procedures, informed consent procedures and materials, and data collection tools were reviewed and approved by the Niger Comité National d’Ethique pour la Recherche en Santé (CNERS) and by the Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (Number: 19-3042). All study methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Additionally, all respondents voluntarily provided written informed consent to participate in the survey. The informed consent form specifies that the conversation will be recorded, data will be de-identified and will be kept confidential until destroyed. The form also indicates that de-identified data from the study will be utilized to answer research questions without asking for additional consent. Only 2 respondents who participated in the open-ended questions were ages 15–17 and both of these young women were married; women ages 15–17 seeking family planning services were considered emancipated minors. Additionally, the Niger Comité National d’Ethique pour la Recherche en Santé (CNERS) and the Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill both approved that these respondents could provide informed consent on their own behalf. In Niger, married adolescents are called emancipated youth, and according to the ethics committee, they can consent to participate in a study. This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Pathfinder International for their collaboration and cooperation with this study. We would also like to thank the study participants who gave their time for the data collection.

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the European Conference on Tropical Medicine and International Health as an oral presentation with interim findings. The poster’s abstract was published in “Abstracts of the 12th European Congress on Tropical Medicine and International Health, 28 September - 1 October 2021, Bergen, Norway” in Tropical Medicine and International Health, Volume 26, Issue S1: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/toc/13653156/2021/26/S1.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation [INV-009814]. Under the grant conditions of the Foundation, a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Generic License has already been assigned to the author accepted manuscript version that might arise from this submission. We also received general support from the Population Research Infrastructure Program through an award to the Carolina Population Center [P2C HD050924] at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Carolina Population Center or the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in relation to this work.

References

1. Donabedian A. The Definition of Quality and Approaches to Its Assessment. Ann Harbor: Health Administration Press; 1980.

2. Williams B. Patient satisfaction: a valid concept? Soc Sci Med. 1994;38(4):509–516. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(94)90247-X

3. Andaleeb SS. Service quality perceptions and patient satisfaction: a study of hospitals in a developing country. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(9):1359–1370. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00235-5

4. Williams T, Schutt-Aine J, Cuca Y. Measuring family planning service quality through client satisfaction exit interviews. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2000;26(2):63–71. doi:10.2307/2648269

5. Reerink IH, Sauerborn R. Quality of primary health care in developing countries: recent experiences and future directions. Int J Qual Health Care. 1996;8:131–139. doi:10.1093/intqhc/8.2.131

6. Dettrick Z, Firth S, Soto EJ, Myer L. Do strategies to improve quality of maternal and child health care in lower- and middle-income countries lead to improved outcomes? A review of the evidence. PLoS One. 2013;8:e83070. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0083070

7. Busse R. Chapter 9: understanding satisfaction, responsiveness and experience with the health system. In: Health System Performance Comparison: An Agenda for Policy, Information and Research. McGraw-Hill Education; 2013.

8. Alden D, Do M, Bhawuk D. Client satisfaction with reproductive health--‐care quality: integrating business approaches to modeling and measurement. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(11):

9. Murphy C, Chakraborty N. Understanding Client satisfaction and perceived quality of care within reproductive health services; 2013. Population Services International. Available from: https://www.psi.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Understanding-Client-Satisfaction_PSI.pdf.

10. Crow R, Gage H, Hampson S, et al. The measurement of satisfaction with healthcare: implications for practice from a systematic review of the literature. Health Technol Assess. 2002;6:32. doi:10.3310/hta6320

11. Hawthorne G. Review of Patient Satisfaction Measures. Canberra, Australia: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing; 2006.

12. Weston RL, Dabis R, Ross J. Measuring patient satisfaction in sexually transmitted infection clinics: a systematic review. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85(6):459. doi:10.1136/sti.2009.037358

13. Travaglia D. Complaints and Patient Satisfaction: A Comprehensive Review of the Literature. Sydney, Australia. University of New South Wales: Centre for Clinical Governance Research; 2009.

14. Bruce J. Fundamental elements of the quality of care: a simple framework. Stud Fam Plann. 1990;21(2):61–91. doi:10.2307/1966669

15. Jain AK, Hardee K. Revising the FP quality of care framework in the context of rights-based family planning. Stud Fam Plann. 2018; 49(2): 171–179. doi:10.1111/sifp.12052

16. RamaRao S, Mohanam R. The quality of family planning programs: concepts, measurements, interventions and effects. Stud Fam Plann. 2003;34(4):227–248. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4465.2003.00227.x

17. Holt K, Zavala I, Quintero X, Hessler D, Langer A. Development and valuation of the client reported quality of contraceptive counselling scale to measure quality and fulfilment of rights in family planning programs. Stud Fam Plann. 2019; 50(2): 137–158. doi:10.1111/sifp.12092

18. Diamond-Smith N, Warnock R, Sudhinaraset M. Interventions to improve the person-centered quality of family planning services: a narrative review. Reprod Health. 2018;14:144. doi:10.1186/s12978-018-0592-6

19. Senderowicz L. Contraceptive autonomy: conceptions and measurement of a novel family planning indicator. Stud Fam Plann. 2020;51(2):161–176. doi:10.1111/sifp.12114

20. Measure Evaluation. Quick Investigation of Quality (QIQ): A User’s Guide for Monitoring Quality of Care in Family Planning.

21. Agha S, Do M. The quality of family planning services and client satisfaction in the public and private sectors in Kenya. Int J Qual Health Care. 2009;21(2):87–96. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzp002

22. Batbaatar E, Dorjdagva J, Luvsannyam A, et al. Determinants of patient satisfaction: a systematic review. Perspect Public Health. 2017;137(2):89–101. doi:10.1177/1757913916634136

23. Hutchinson PL, Do M, Agha S. Measuring client satisfaction and the quality of family planning services: a comparative analysis of public and private health facilities in Tanzania, Kenya and Ghana. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011; 11: 203. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-11-203

24. Srivastava A, Avan BI, Rajbangshi P, Bhattacharyya S. Determinants of women’s satisfaction with maternal health care: a review of literature from developing countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:97. doi:10.1186/s12884-015-0525-0

25. Wogu D, Lolaso T, Meskele M. Client satisfaction with family planning and associated factors in Tembaro District, South Ethiopia. J Contracept. 2020;11:69–76.

26. Harris S, Reichenbach L, Hardee K. Measuring and monitoring quality of care in family planning: are we ignoring negative experiences? J Contracept. 2016;7:97–108.

27. Leon FR, Lundgren R, Huapaya A, et al. Challenging the courtesy bias interpretation of favorable clients’ perceptions of family planning delivery. Eval Rev. 2007;31(1):24–42. doi:10.1177/0193841X06289044

28. Kelley E, Boucar M. Helping district teams measure and act on client satisfaction data in Niger. In: Operations Research Results 1(1). Bethesda, Maryland: Published for the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) by the Quality Assurance Project (QAP); 1999.

29. Tumlinson K, Speizer IS, Archer LH, Behets F. Simulated clients reveal factors that may limit contraceptive use in Kisumu, Kenya. Glob Health. 2013;1(3):407–416.

30. Institut National de la Statistique (INS) et ICF International. Enquête Démographique et de Santé et à Indicateurs Multiples du Niger 2012 [Niger Demographic and Health Survey and Multiple Indicators 2012]. Calverton, Maryland, USA: INS et ICF International; 2013. French.

31. Performance Monitoring and Accountability 2020. Snapshot of Indicators: PMA2020/Niger; 2017. Available from: https://www.pmadata.org/sites/default/files/data_product_indicators/PMA2020-Niger-National-R2-FP-SOI-EN.pdf.

32. Family Planning 2020. Niger: commitment maker since 2012. Available from: https://www.familyplanning2020.org/niger.

33. Ahinkorah BO, Seidu AA, Budu E, et al. Which factors predict fertility intentions of married men and women? Results from the 2012 Niger demographic and health survey. PLoS One. 2021;16(6):e0252281. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0252281

34. Cleland J, Harbison S, Shah IH. Unmet need for contraception: issues and challenges. Stud Fam Plan. 2014;45(2):105–122. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4465.2014.00380.x

35. Sedgh G, Ashford L, Hussain R. Unmet need for contraception in developing countries: examining women’s reasons for not using a method, New York: guttmacher institute; 2016. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/report/unmetneed-for-contraception-in-developing-countries.

36. Cotten N, Stanback J, Maidou H, et al. Early discontinuation of contraceptive use in Niger and the Gambia. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 1992;18(4):145–149. doi:10.2307/2133542

37. Speizer IS, Amani H, Winston J, et al. Assessment of segmentation and targeted counseling on family planning quality of care and client satisfaction: a facility-based survey of clients in Niger. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:1075. doi:10.1186/s12913-021-07066-z

38. Institut National de la Statistique. Annuaire Statistique Regionale de Dosso [Directory of Regional Statistics of Dosso]. Niamey, Niger: Institut National de Statistique;2018. French.

39. Ministère de la Santé Publique. Annuaire des statistiques sanitaires du niger, Année [Directory of health statistics of Niger, yearly]. Niamey, Niger: Ministère de la Santé Publique, Secrétariat Général, Direction des Statistiques; 2013. French.

40. Ministère de la Santé Publique et de la Lutte contre les Endémies. Normes et standards des infrastructures, équipements et personnel Du Système de santé [Norms and standards of infrastructure, equipment, and personnel of the Health System]. Niamey, Niger: ministère de la Santé Publique et de la Lutte contre les Endémies; 2006. French.

41. Braun V, Clark V, Hayfield N, Terry G. Thematic analysis. In: Liamputtong P, editor. Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences. Singapore: Springer; 2019.

42. ICF. “SPA Exit Interviews English, French”. The DHS program website. Funded by USAID. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-spaq3-spa-questionnaires-and-manuals.cfm.

43. Mirzoev T, Kane S. What is health systems responsiveness: review of existing knowledge and proposed conceptual framework. BMJ Global Health. 2017;2:e000486. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000486

44. Argago TG, Hajito KW, Kitila SB. Client’s satisfaction with family planning services and associated factors among family planning users in Hossana Town public health facilities, south Ethiopia: facility-based cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Pract. 2015;7(5):74–83. doi:10.5897/IJNM2015.0163

45. Slater AM, Estrada F, Suarez-Lopez L, et al. Overall user satisfaction with family planning services and associated quality of care factors: a cross-sectional analysis. Reprod Health. 2018; 15: 172. doi:10.1186/s12978-018-0615-3

46. Bintabara D, Ntwenya J, Maro II, et al. Client satisfaction with family planning services in the area of high unmet need: evidence from Tanzania Service Provision Assessment Survey, 2014–2015. Reprod Health. 2018;15:127. doi:10.1186/s12978-018-0566-8

47. Sudhinaraset M, Afulani P, Diamond-Smith N, Bhattacharyya S, Donnay F, Montagu D. Advancing a conceptual model to improve maternal health quality: the person-centered care framework for reproductive health equity. Gates Open Res. 2017;1:1. doi:10.12688/gatesopenres.12756.1

48. Boydell V, Keesbury J. Social Accountability: What are the Lessons for Improving Family Planning and Reproductive Health Programs? A Review of the Literature, Working Paper. Washington, DC: Population Council, Evidence Project; 2014.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published by Dove Medical Press Limited, and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License.

The full terms of the License are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

The license permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published by Dove Medical Press Limited, and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License.

The full terms of the License are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

The license permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.