Back to Journals » Clinical Ophthalmology » Volume 14

High Prevalence of Clinically Active Trachoma and Its Associated Risk Factors Among Preschool-Aged Children in Arba Minch Health and Demographic Surveillance Site, Southern Ethiopia

Authors Glagn Abdilwohab M , Hailemariam Abebo Z

Received 17 September 2020

Accepted for publication 19 October 2020

Published 2 November 2020 Volume 2020:14 Pages 3709—3718

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S282567

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Mustefa Glagn Abdilwohab, Zeleke Hailemariam Abebo

School of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Arba Minch University, Arba Minch Town, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Mustefa Glagn Abdilwohab School of Public Health

College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Arba Minch University, P.O. Box 21, Arba Minch Town, Ethiopia

Tel +251 913976776

Email [email protected]

Background: Trachoma is the leading infectious cause of irreversible blindness. In areas where trachoma is endemic, active trachoma is common among preschool-aged children, with varying magnitude. There is a dearth of information on the prevalence of active trachoma among preschool-aged children (the most affected segment of the population).

Purpose: The study aimed to assess the prevalence of clinically active trachoma and its associated risk factors among preschool-aged children in Arba Minch Health and Demographic surveillance site, Southern Ethiopia.

Patients and Methods: A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted among 831 preschool-aged children from May 01 to June 16, 2019. A pre-tested and structured interviewer-administered Open Data Kit survey tool was used to collect data. The study participants were selected using a simple random sampling technique by allocating a proportion to each kebeles. Both bivariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to identify associated factors. The level of statistical significance was set at a p-value of less than 0.05 in multivariable logistic regression.

Results: The overall prevalence of clinically active trachoma among preschool-aged children was 17.8% with 95% CI (15%, 20%). Time taken to obtain water for greater than thirty minutes (AOR=2.8,95% CI: 1.62, 5.09), presence of animal pens in the living compound (AOR=5.1, 95% CI: 3.15, 8.33), improper solid waste disposal (AOR=7.8,95% CI: 4.68,13.26), improper latrine utilization (AOR=2.5, 95% CI: 1.63,3.94), a child with unclean face (AOR=3.5, 95% CI: 2.12,5.97) had higher odds of active trachoma.

Conclusion: The prevalence of clinically active trachoma among pre-school aged children was high. “Facial cleanliness” and “Environmental improvement” components of the SAFE strategy are vital components in working towards the 2020 target of eliminating trachoma. Therefore, stakeholders at different hierarchies need to exert continuing efforts to integrate the trachoma prevention and control programs with other public health programs, with water sanitation and hygiene programs and with the education system.

Keywords: preschool children, active trachoma, associated factor, Ethiopia

Introduction

Trachoma is the leading infectious cause of irreversible blindness. It is characterized by repeated conjunctival infection with particular strains of Chlamydia trachomatis. Eventually, in some individuals, sight is lost from irreversible corneal opacification.1 The infection is transmitted by direct or indirect transfer of eye and nose discharges of infected people, particularly young children who harbor the principal reservoir of infection. These discharges can be spread by particular species of flies (Musca sorbens).2 According to World Health Organization (WHO), trachoma simplified grading system it is classified as trachomatous inflammation follicular (TF), trachomatous inflammation intense (TI), trachomatous scarring (TS), trachomatous trichiasis (TT), and corneal opacity (CO).3,4

The latest global estimate indicates that 158 million people live in trachoma-endemic areas and are at risk of trachoma blindness that needs interventions.5 Today, 1.9 million people are blind or visually impaired due to trachoma.6,7 More than 80% of the burden of active trachoma is concentrated in 14 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, with Ethiopia being the country bearing the greatest burden.5 More than 75 million people are at risk of developing trachoma in Ethiopia, the world’s most affected country,8 and contributing 49% of the global burden of active trachoma.9 In Ethiopia, trachoma remains a major public health problem.6,7,10,11 The Ethiopian National Survey on Blindness, Low Vision, and Trachoma, carried out from 2005 to 2006 estimated that the national prevalence of active trachoma was 40.14%, with some regional variation. It is estimated that more than 138,000 people in Ethiopia are blinded by trachoma.12 In areas where trachoma is endemic, active (inflammatory) trachoma is extremely common among preschool-aged children, with prevalence rates that can be as high as 60–90%.13

In 1996, the World Health Organization launched the WHO Alliance for the Global Elimination of Trachoma (GET) by 2020. The Alliance is a partnership that supports the implementation of the SAFE (surgery, antibiotics, facial cleanliness, environmental improvement) strategy for elimination.14 Given this public health tragedy, the Ethiopian government also signed the vision 2020 initiative in 2002, which is a 20 years strategic plan to eliminate trachoma.15 After the implementation of the SAFE strategy in 2003, Ethiopia made remarkable achievements. However, many districts continue to have a high prevalence of active trachoma.16 Since 2007, orbis and Irish aid along with other non-governmental organization and the regional health bureau is working towards a goal to eliminate blinding trachoma in the study area. The organization was tried to implement the SAFE strategy to prevent blinding trachoma.17 The intervention mainly focuses on antibiotic distribution and trichiasis surgery. According to summative evaluation of the project under achievement were reported regarding “F” and “E” components of the SAFE strategy.18 Despite their efforts to control and prevent trachoma, still it remains the public health concern in the study area.

There are several risk factors associated with an increased prevalence of trachoma. These include personal hygiene-related, environmental-related, over-crowdedness, socio-demographic, toilet facilities, accessibility of water, and health facilities related factors.19–23 Most importantly, the prevalence and risk factors associated with trachoma tend to vary from one epidemiological setting to another, thus to meet the GET2020 targets and targets for global action in sustainable development goal (SDG) target 3.3, which calls to “end the epidemics of neglected tropical diseases” by 2030, as part of Goal 3 (Ensure healthy lives and ensure well-being for all at all ages).24 It is important to understand the local distribution of the disease in a specific community and specific age groups. To the best of our knowledge, there was one study done in Ethiopia.7 In line with the focus of reduction of active trachoma to a level, less than five percent among children aged between one and nine years in the current health sector transformation plan of the country25 and the expected variation across regions of the country in the magnitude of active trachoma, the findings of this study is timely and would contribute to the local program planning and policymaking at large. Moreover, in response to the limited evidence in the prevalence of active trachoma among preschool children in the country in recent years and to fill this gap in the scientific literature, our study aimed to assess the prevalence of active trachoma and the factors associated with it in Arba Minch Health and Demographic Surveillance Site, Southern Ethiopia.

Methods and Materials

Study Setting, Design, and Population

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted among preschool children (children aged 2–5 years) in Arba Minch – Health and Demographic Surveillance Site (AM-HDSS), Southern Ethiopia from May 01 to June 16, 2019. AM-HDSS is located in both Arba Minch Zuria and Gacho Baba districts. Ethiopia has established Health and Demographic Surveillance Systems (HDSS) at different corners of the country in order to contribute to filling the information gap to some extent. Currently, there are six HDSS sites. One of the sites is AM-HDSS owned by Arba Minch University. The Ethiopian universities are networked to produce data which may reflect some pictures of the country related to health and demography. This network namely the “Ethiopian Universities Research Centers Network” was established in 2007. Arba Minch Zuria and Gacho Baba districts have a total of 31 kebeles (smallest administrative unit in Ethiopia) with three different climatic zones, high land, midland, and lowland, among which 9 kebeles are selected as a center for producing data to fill the country health information need. The report of AM-HDSS showed the surveillance site has a total population of 74,157. The total number of children aged between two and five years in AM-HDSS was 7289. Out of the children aged between two and five years; Male account 51.06% and female account 48.94%. All preschool aged children (2 to 5 years old), who lived in AM-HDSS for at least 6 months were included in the study.

Sample Size Estimation

The sample size was determined by using a single population proportion formula by considering 18% prevalence of active trachoma among preschool children taken from a study done in Dembia District, Northwest Ethiopia.7 Ten percent nonresponse rates and 95% confidence level with 2.5% margin of error. Based on these assumptions, the final sample size calculated for this study was 907 children aged between 2 and 5 years.

Sampling Procedure

All Arba Minch – health and demographic surveillance site kebeles were included in this study because the kebeles are already selected as a center for producing data by the Arba Minch University. First, the total households (HHs) in each kebele with preschool children and lists of children aged between two and five years were obtained from the AM-HDSS coordination office. Then, the study participants were selected using a simple random sampling technique (computer-generated random numbers) after allocating a proportion to each AM-HDSS kebeles based on the size of preschool children. Only one study participant from each household was selected using lottery method in a household with two and above preschool children. When mother/caregiver–child pairs were not available at the time of data collection, two repeated visits were made.

Operational Definition

Active trachoma was measured as the presence of either Trachomatous inflammation follicles or intense. Unclean face: The presence of “sleep” or ocular discharge around the eyes, flies, or the presence of nasal discharge on the upper lip or cheeks of the child at the time of visit. Improper solid waste disposal; in this study, improper solid waste disposal was defined as not disposing solid waste at a legally unauthorized place or dumping wastes in the open field. Proper latrine utilization; proper latrine utilization was defined as households with either shared or private functional latrines and the family disposed the faeces of under-five children in a latrine, no observable faeces in the compound, no observable fresh faeces on the inner side of the squatting hole and the presence of clear foot-path to the latrine is uncovered with grasses or other barriers of walking otherwise it was defined as improper latrine utilization.25

Data Collection Procedure

A pretested and structured interviewer-administered Open Data Kit (ODK) survey tool was used to collect the socio-demographic, housing, environmental, personal hygiene-related characteristics, accessibility of health facilities, and trachoma-related characteristics of the participants (refer trachoma survey questionnaire, attached as Supplementary material). The tools were developed by reviewing different works of literature. Language experts translated the questionnaire from English to Amharic and back to English to ensure consistency in meaning. A pretest was conducted on unselected district by taking 5% of the total sample size. After we made appropriate corrections, the revised version of the questionnaire was used for final data collection. Five public health experts and 16-trained data collectors (six clinical optometrists and 10 data collectors who were AM-HDSS field workers (routinely collects HDSS data)) were recruited for supervision and data collection, respectively.

Clinical Assessment of Trachoma

Following the face-to-face interview for collecting data related to socio-demographic, hygiene, and environmental factors; trained clinical optometrists examined each child by ocular examination. The clinical optometrists performed a detailed ophthalmic examination with strict compliance with the standard methods and procedures. The clinical Optometrists carefully inspected eyelashes, cornea, limbus, upper eyelid, and tarsal conjunctiva using a pen torch and binocular loupe that has 2.5× magnifying power to identify clinical signs of trachoma: trachomatous inflammation-intense (TI), trachomatous inflammation-follicular (TF), trachomatous conjunctival scar (TS), trachomatous trichiasis (TT), and corneal opacity (CO). Eyelid eversion (turning out) was done using an aseptic technique using alcohol used for hand disinfection. The interrater variability of eye examination was solved by expert trachoma graders. The guideline used for clinical diagnosis and reporting of eye examination results was the simplified trachoma grading system, which was developed by the WHO for fieldwork.3,4 TF: the presence of five or more follicles in the upper tarsal conjunctiva; TI: when the tarsal conjunctiva red, rough, and thickened; TS: the presence of scarring (white lines, bands or sheets) in the tarsal conjunctiva; TT: the presence of at least one eyelash rubs on the eyeball; CO: if the pupil margin is a blurred view through the opacity.

Data Quality Management

Data collectors and supervisors were provided intensive training on the techniques of data collection and components of the instrument. Before the commencement of the data collection, a pretest was conducted. A standard tool, which was commented by many experts, was used to collect the information. The ODK survey tool that was very important to control the quality of data was used to collect data by using tablets. The Authors and supervisors critically checked the data for completeness before uploaded to the ODK cloud server.

Statistical Analysis

The collected data were downloaded from ODK aggregate and then converted to an excel file. It was then edited and cleaned for inconsistencies, missing values, outliers, and then exported to SPSS version 25 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for further analysis. Descriptive statistics were computed and summarized in tables, figures and text with frequencies, mean, or standard deviations where appropriate. The association between active trachoma and its independent variables were examined by binary logistic regression. Crude odds ratios were computed to determine the strength of association of the selected explanatory variables with the dependent variable in the initial bivariate logistic regression analysis. Variables that showed an association at a p-value ≤ 0.25 in the bivariable logistic regressions were selected as a potential candidate for multivariable logistic regression analysis to control confounders in the regression models. The final model was fitted using stepwise selection methods (backward conditional). Model fitness was checked using the Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness of fitness test (P-value ≥0.05). The association between active trachoma and the independent variables were reported by odds ratio with its 95% CI and variables having a p-value less than 0.05 in the multivariable logistic regression model were considered as statistically significant.

Ethical Consideration

Ethical clearance was obtained from the ethical review committee of Arba Minch University, College of Health Science. A letter of cooperation was obtained from Arba Minch – Health and Demographic Surveillance Site (AM-HDSS), Southern Ethiopia coordination office. The purpose of the study was explained and informed written consent was taken from the head of the household or child caregiver. The reason for the eye examination and what the examination will involve was explained to caregivers. To ensure confidentiality, their names, and other personal identifiers were not registered in the survey tool. Their participation was voluntary. After the interview and eye examination, the research team provided health education on prevention and treatment measures of trachoma, and children with active trachoma were linked with nearby primary eye care unit. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Socio-Demographic Characteristics

Eight hundred and thirty-one children (831) were interviewed giving a response rate of 91.6%. The mean age (± SD) of the children was 40.96 (± 10.70) months and slightly more than half (50.9%) were boys. More than three-fourths of the household head were farmers (77.0%) with the average family size of seven. The majority of the child-caregivers were their mother (97.5%), and unable to read and write (62.7%) (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Study Participants in AM-HDSS, Southern Ethiopia from May 01 to June 16, 2019 |

Child Personal Hygiene-Related Characteristics

Among the children who participated in study 679 (81.7%) of them had an unclean face. According to the mothers’ report about their children, 594 (71.5%) of the children washed their faces only once within 24 hours period of time and four hundred and thirteen (49.7%) of them did not use soap for washing face.

Health and Environmental-Related Characteristics

Most of the households used pipe water 541 (65.1%), and 467 (56.2%) of the household consume less than 20 liters of water per day. Almost half (47.8%) of the households have animal pens within their living compound, and 305 (36.7%) of the households disposed of solid waste improperly. A total of 638 (76.8%) of the households had a functional latrine (Table 2).

|

Table 2 Health and Environmental-Related Characteristics of Study Participants in AM-HDSS, Southern Ethiopia from May 01 to June 16, 2019 |

Prevalence of Trachoma Among Preschool Children

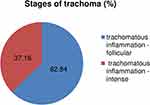

Among all children examined for trachoma status, 148 (17.8%) with 95% CI (15%, 20%) children had clinically active trachoma. Among all preschool children examined for trachoma status, 93 (11.2%) had TF with 95% CI (9%, 13%), and 55 (6.6%) had TI with 95% CI (5%, 8%) respectively. Out of 148 children who had active trachoma, 62.84% were trachomatous follicle (TF). There were no TS, TT, and CO stages observed during the study period (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1 Stages of trachoma observed in pre-school children in AM-HDSS, Southern Ethiopia from May 01 to June 16, 2019. |

Factors Associated with Active Trachoma

After adjusting for socio-demographic, child hygienic condition, health and environmental-related factors; the multivariable logistic regression analysis identified time to obtain water, presence of animal pens in the living compound, mechanism of disposing of dry waste, latrine utilization, and unclean face of child as an independent predictor for pre-school- aged children for active trachoma. The odds of developing trachoma among preschool children from households who obtain water for household consumption from greater than thirty minutes walking distance away from their homes were almost 3 times higher than those who obtain water from less than or equal to thirty minutes on a walk (AOR=2.8,95% CI: 1.62, 5.09). Likewise, the odds of having active trachoma among preschool children from households with the presence of animal pens in their living compound were 5 times higher than those households do not have animal pens in their living compound (AOR=5.1, 95% CI: 3.15, 8.33). Compared with their counter parts, the odds of developing active trachoma was also higher among preschool children from households disposed of solid waste improperly (AOR=7.8, 95% CI: 4.68, 13.26), and among preschool children from households’ who did not utilize latrine properly (AOR=2.5, 95% CI: 1.63, 3.94). The odds of having active trachoma were also 3.5 times higher among preschool children with flies, nasal discharge, or eye discharge observed on the face compared with their counterparts (AOR=3.5, 95% CI: 2.12,5.97) (Table 3).

|

Table 3 Factors Associated with Active Trachoma (TF) or (TI) Among Preschool-Aged Children in Arba Minch Health and Demographic Surveillance Site, Southern Ethiopia, 2019 |

Discussion

This study tried to identify the prevalence and associated factors of active trachoma among pre-school aged children in rural communities in the Arba Minch Health and Demographic surveillance site. The finding from the study revealed that the overall prevalence of clinically active trachoma among preschool children was 17.8% with 95% CI (15%, 20%). This is greater than WHO criteria for the elimination of trachoma as a public health problem, the prevalence of TF to a level <5%.8 The finding is consistent with the study conducted in Dembia district, Northwest Ethiopia.7 The finding of the current study is higher compared to findings from studies conducted among preschool-aged children in Sao Paulo Brazil27 and Gambia,28 and lower than the studies conducted in Tanzania28 and North‐Eastern Nigeria.26 The difference could be attributed to differences in study setting, study period, geographical variations, infrastructure, social connections, and health-care facilities. The other reasons for variations might be due to differences in utilization of sanitary services and variation in the implementation of the SAFE strategy for eliminating trachoma. The finding of the study confirmed that trachoma is still a disease of public health interest. Ethiopia is home to about 13 million children under 5 years of age – approximately 16% of the total population.30 Given this huge number of children, adequate attention was not yet given for this specific population. To meet the GET2020 targets8 and the health sector transformation plan of Ethiopia,25 interventions targeted to preschool children have paramount importance. Time taken to obtain water for household consumption was significantly associated with the development of clinically active trachoma. This finding is consistent with the study conducted in Tanzania28,31 and Ethiopia.7,23,32 These studies reported that the prevalence of active trachoma in children significantly increased with increasing reported water collection time. On the contrary, there was no significant association between the quantities of water consumed per house household with active trachoma. This indicates that using the highest volume of water for household consumption is not a guarantee for preventing trachoma. The possible explanation might be that the water that is fetched and used by the rural community might not be safe enough for keeping personal hygiene.

In the present study, preschool children from households with the presence of animal pens in the living compound were more likely to develop active trachoma compared with their counterparts. This association might be due to increased exposure of children to flies that transmit trachoma and breed in exposed animal feces. An animal pen in the living compound is very common in the study area so that the finding suggests that exposed animal feces increase the vulnerability of the children to trachoma. Therefore, the local government needs to intervene in this particular issue. Similarly, the odds of developing trachoma among pre-school children whose households do not dispose of solid waste properly were almost eight times higher than that of children whose households properly dispose of solid waste. This could be explained by the fact that disposing of solid waste on open field attracts a high number of eyes seeking flies that lead to a high chance of transmission of active trachoma in the children. The finding is concordant to the studies conducted in Lemo district, Southern Ethiopia,6 Gondar Zuria District North Gondar,33 and Loma Woreda, Dawro Zone, Ethiopia.34

In the present study, we observed that preschool children from households who do not utilize latrine properly were more likely to develop active trachoma compared with households utilize latrine properly. This result was in agreement with the study conducted in Lemo district, Southern Ethiopia,6 and West Gojjam Zone, North West Ethiopia.32 This could be reasoned out that proper latrine utilization may reduce eye-seeking flies in the surrounding environment.

Facial cleanliness of the children was also significantly associated with the development of active trachoma. Children with unclean faces were more likely to have trachoma when compared with those children whose faces were clean. Studies that had been conducted elsewhere7,10,20,28,29 reported similar findings. The possible explanation is because unclean faces attract eye-seeking flies (Musca sorbens) which are potential mechanical vectors of Chlamydia trachomatis infection.35 Nasal and ocular discharges may both result from the inflammation of active trachoma and make the child face dirty which potentially attracts eye-seeking flies.

This study has some limitations which have to be taken into consideration while interpreting the findings. As being cross-sectional in the design, it does not confirm the definitive cause and effect relationship. This study is also subject to residual confounding since some potential factors such as fly density, time taken to obtain water, water quality issues, and amount of water used per capita for face washing was not well addressed or measured. Due to a lack of sufficient resources, the positive result of trachoma status could not be confirmed by advanced laboratory tests so that differential diagnosis may overestimate the result. Some variables such as using soap for face washing and face washing frequency of children could be subjected to responder bias.

Conclusion

The study revealed that the prevalence of clinically active trachoma among pre-school aged children was high in Arba Minch HDSS site. Time to obtain water, presence of animal pens in the living compound, mechanism of disposing of dry waste, latrine utilization, and unclean face of child were significant factors associated with active trachoma. The findings of the current study suggest “F” and “E” components of the SAFE strategy are vital components in working towards the 2020 target of eliminating trachoma and SDG target 3.3, ending the epidemics of neglected tropical diseases by 2030. Therefore, stakeholders at different hierarchies need to exert continuing efforts to integrate the trachoma program with other public health programs, with water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) programs and/or with the education system.

Data Sharing Statement

All the data are presented in the manuscript and Supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the data collectors, the study participants, and supervisors for their co-operation during data collection. Our thanks also go to Arba Minch University for providing ethical clearance.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Bourne RR, Stevens GA, White RA, et al. Causes of vision loss worldwide, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1(6):e339–e349. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70113

2. Last A, Versteeg B, Shafi Abdurahman O, et al. Detecting extra-ocular Chlamydia trachomatis in a trachoma-endemic community in Ethiopia: identifying potential routes of transmission. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(3):e0008120. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0008120

3. Taylor HR, West SK, Katala S, Foster A. Trachoma: evaluation of a new grading scheme in the United Republic of Tanzania. Bull World Health Organ. 1987;65(4):485.

4. Thylefors B, Dawson CR, Jones BR, West SK, Taylor HR. A simple system for the assessment of trachoma and its complications. Bull World Health Organ. 1987;65(4):477.

5. WHO. Weekly Epidemiological Record No 26. Vol. 93; 2018:369–380.

6. WoldeKidan E, Daka D, Legesse D, Laelago T, Betebo B. Prevalence of active trachoma and associated factors among children aged 1 to 9 years in rural communities of Lemo district, southern Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):886. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-4495-0

7. Ferede AT, Dadi AF, Tariku A, Adane AA. Prevalence and determinants of active trachoma among preschool-aged children in Dembia District, Northwest Ethiopia. Infect Dis Poverty. 2017;6(1):128. doi:10.1186/s40249-017-0345-8

8. Eliminating Trachoma Accelerating Towards 2020. WHO Alliance for the Global Elimination of Trachoma by 2020. April, 2016. Available from: http://www.trachomacoalition.org/.

9. Ejigu M, Kariuki MM, Lako DR, Gelaw Y. Rapid trachoma assessment in KersaDistrict. Southwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2013;23:1–9.

10. Mengistu K, Shegaze M, Woldemichael K, Gesesew H, Markos Y. Prevalence and factors associated with trachoma among children aged 1–9 years in Zala district, Gamo Gofa Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016;10:1663. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S107619

11. Asfaw M, Zolfo M, Negussu N, et al. Towards the trachoma elimination target in the Southern region of Ethiopia: how well is the SAFE strategy being implemented? J Infect Dev Ctries. 2020;14(06.1):3S–9S. doi:10.3855/jidc.11703

12. Berhane Y, Worku A, Bejiga A, et al. National survey on blindness, low vision, and trachoma in Ethiopia: methods and study clusters profile. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2007;21(3):185–203.

13. WHO. Epidemiology and clinic feature fact sheet. January, 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/trachoma.

14. Report of the 20th Meeting of the WHO Alliance for the Global Elimination of Trachoma by 2020, Sydney, Australia, 26–28 April 2016. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

15. Gedefaw M, Shiferaw A, Alamrew Z, Feleke A, Fentie T, Atnafu K. Current state of active trachoma among elementary school students in the context of an ambitious national growth plan. The case of Ethiopia. Health. 2013;5:1768–1773. doi:10.4236/health.2013.511238

16. Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health Second Edition of Ethiopia National Master Plan for Neglected Tropical Diseases. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/publications/second-edition-national-neglected-tropical-diseases-master-plan-ethiopia-2016.

17. ORBIS AND IRISH AID. Available from: https://irl.orbis.org/en/news/2019/orbis-and-irish-aid.

18. Summative evaluation of a project to eliminate trachoma, implemented by Orbis Ethiopia, in Gamo Gofa, Derashe, Konso and Alle in Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region Ethiopia from 2006–2016.

19. Adera TH, Macleod C, Endriyas M, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for trachoma in Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region, Ethiopia: results of 40 population-based prevalence surveys carried out with the Global Trachoma Mapping Project. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016;23(sup1):84–93. doi:10.1080/09286586.2016.1247876

20. Gebrie A, Alebel A, Zegeye A, Tesfaye B, Wagnew F. Prevalence and associated factors of active trachoma among children in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):1073. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-4686-8

21. Mahande MJ, Mazigo HD, Kweka EJ. Association between water related factors and active trachoma in Hai district, Northern Tanzania. Infect Dis Poverty. 2012;1(1):10. doi:10.1186/2049-9957-1-10

22. Hägi M, Schémann JF, Mauny F, et al. Active trachoma among children in Mali: clustering and environmental risk factors. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4(1):e583. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000583

23. Ketema K, Tiruneh M, Woldeyohannes D, Muluye D. Active trachoma and associated risk factors among children in Baso Liben District of East Gojjam, Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):1105. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-1105

24. Ending the Neglect to Attain the Sustainable Development Goals: A Road Map for Neglected Tropical Diseases 2021–2030. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

25. The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Ministry of Health. Health Sector Transformation Plan. 2015.

26. Anteneh A, Kumie A. Assessment of the impact of latrine utilization on diarrhoeal diseases in the rural community of Hulet Ejju Enessie Woreda, East Gojjam Zone, Amhara region. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2010;24(2):2. doi:10.4314/ejhd.v24i2.62959

27. Calligaris LSA, Medina NH, Waldman EA. Trachoma prevalence and risk factors among preschool children in a central area of the City of Sao Paulo, Brazil. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2006;13:365–370. doi:10.1080/09286580601013078

28. Harding-Esch E, Edwards T, Mkocha H. Trachoma prevalence and associated risk factors in the Gambia and Tanzania: baseline results of a cluster randomised controlled trial. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4(11):e861. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000861

29. Mpyet C, Goyol M, Ogoshi C. Personal and environmental risk factors for active trachoma in children in Yobe state, north‐eastern Nigeria. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15(2):168–172. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02436.x

30. UNICEF: The situation of children in Ethiopia. 2018. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/ethiopia/children-ethiopia.

31. Polack S, Kuper H, Solomon AW, et al. The relationship between the prevalence of active trachoma, water availability and its use in a Tanzanian village. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006;100(11):1075–1083. doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.12.002

32. Nigusie A, Berhe R, Gedefaw M. Prevalence and associated factors of active trachoma among children aged 1–9 years in rural communities of Gonji Kolella district, West Gojjam Zone, North West Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8(1):641. doi:10.1186/s13104-015-1529-6

33. Asres M, Endeshaw M, Yeshambaw M, Muluken A. Prevalence and risk factors of active trachoma among children in Gondar Zuria District North Gondar, Ethiopia. Prev Med. 2016;1(1):5.

34. Admasu W, Hurissa BF, Benti AT. Prevalence of trachoma and associated risk factors among yello elementary school students, in Loma Woreda, Dawro zone, Ethiopia. J Nurs Care. 2015;1:2167.

35. Farrar J, Hotez P, Junghanss T, Kang G, Lalloo D, White NJ. Manson’s Tropical Diseases E-Book. Elsevier health sciences; 2013.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.