Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 9

Grappling with the issue of homosexuality: perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs among high school students in Kenya

Authors Mucherah W, Owino E, McCoy K

Received 10 May 2016

Accepted for publication 14 July 2016

Published 9 September 2016 Volume 2016:9 Pages 253—262

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S112421

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Winnie Mucherah,1 Elizabeth Owino,2 Kaleigh McCoy,1

1Department of Educational Psychology, Ball State University, Muncie, IN, USA, 2Department of Educational Psychology, Moi University, Eldoret, Kenya

Abstract: While the past decade has seen an improvement in attitudes toward homosexuality, negative attitudes are still prevalent in many parts of the world. In general, increased levels of education tend to be predictive of relatively positive attitudes toward homosexuality. However, in most sub-Saharan countries, it is still believed that people are born heterosexual and that nonheterosexuals are social deviants who should be prosecuted. One such country is Kenya, where homosexuality is illegal and attracts a fine or jail term. The purpose of this study was to examine high school students’ perceptions of homosexuality in Kenya. The participants included 1,250 high school students who completed a questionnaire on perceptions of homosexuality. The results showed that 41% claimed homosexuality is practiced in schools and 61% believed homosexuality is practiced mostly in single-sex boarding schools. Consistently, 52% believed sexual starvation to be the main cause of homosexuality. Also, 95% believed homosexuality is abnormal, 60% believed students who engage in homosexuality will not change to heterosexuality after school, 64% believed prayers can stop homosexuality, and 86% believed counseling can change students’ sexual orientation. The consequences for homosexuality included punishment (66%), suspension from school (61%), and expulsion from school (49%). Significant gender and grade differences were found. The implications of the study findings are discussed.

Keywords: homosexuality, attitudes, beliefs, high school, Kenya

Introduction

While the past decade has seen an improvement in attitudes toward homosexuality, negative attitudes are still prevalent in many parts of the world. In general, increased levels of education tend to be predictive of relatively positive attitudes toward homosexuality. However, many studies reveal prevalent negative attitudes and prejudices toward homosexuality.1–6 Homosexuality, as defined by Savin-Williams,7 is a sexual activity between two people of the same sex. For the purposes of this study, homosexuality will be defined as a romantic attraction between individuals of the same sex or a sexual attraction or behavior between people of the same gender. According to research, a majority of same sex individuals experience their first sex attraction or sexual behavior during adolescence.7,8 Savin-Williams’ study of gay male adolescents found that the average age for having a first crush on another boy was 12.7 years and the average age at realizing that they were gay was 12.5 years.7 Many adolescents report feeling confused and in denial of their identity as gay. Savin-Williams concluded that these feelings of confusion and denial could be attributed to the negative attitudes about nonheterosexual individuals.7

Some of the negative attitudes about homosexuality are influenced by lack of exposure to diversity,9 religious beliefs,1,2,5,10 and the social–cultural contexts.3,5,11 It appears that having a close contact with a lesbian or gay person increases positive attitudes and reduces prejudicial behaviors toward nonheterosexual individuals.12 In their US study of 1,069 high school students examining the relationship between intergroup contact and adolescents’ attitudes about homosexuality and treatment of lesbian and gay peers, Heinze and Horn12 found that having a lesbian or gay friend was significantly related to more positive attitudes toward nonheterosexual individuals (sexual minorities) and less teasing of a lesbian or gay peer.12 Similar results were found in a study conducted in Barcelona. The purpose of that study was to evaluate attitudes and prejudices about homosexuality among high school teachers. The results found that a majority of the teachers (75.5%) reported they have or have had a gay/lesbian friend and they demonstrated low levels of homophobia. The authors concluded that this was due to the teachers’ high sensitivity to issues of diversity.9

Having an understanding of the construct of homosexuality in addition to some form of training or exposure to diversity plays a large part in shaping attitudes toward homosexuality. In their study conducted in Ireland examining how teachers, students, parents, and school administrators in high schools understood and experienced homosexuality as it relates to homophobic bullying, the researcher found strong fears of sexual minorities. The results showed that teachers, administrators, and parents agreed that the fear expressed by students had to do with a general lack of education and experience of people who were gay and lesbian. The teachers in the study stated that they were limited in their training on how to address the issues of homophobic teasing and bullying.5 A related study in the US by Gowen and Winges-Yanez13 examining how inclusive and/or exclusive sexuality education is to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ) youth based on their experiences in Oregan high schools found that sex education is focused on heterosexual topics. LGBTQ is only brought up in the context of acquired immune deficiency syndrome/sexually transmitted diseases and statistics on risky behavior. The authors conclude that through silencing, adopting heterocentric perspective, and pathologizing, LGBTQ youths are isolated from lessons and conversations in their school-based sexuality education classes.

The social–cultural conceptualizations, definitions, and labels of gay/lesbian and bisexual tend to influence people’s attitudes. In their study conducted in the Caribbean at West Indies University examining attitudes toward male homosexuality, Chadee et al1 found that heterosexual males held negative attitudes toward male homosexuality. In addition, the participants indicated that sexual minorities are viewed by society as social outcasts and homosexuality is condemned by families. From the study findings, it appears that the social–cultural context plays a significant role in perceptions and attitudes toward homosexuality. These views are shared by a study conducted by Mora11 in the US examining the abjection of homosexuality among middle school boys of Latino descent. The results showed that the boys associated homosexuality with weakness and therefore sought to display and be recognized as heterosexual Dominican males because it was equated to dominance, superiority, physical toughness, and masculinity. The results also documented numerous use of homophobic language by the boys in order to distance themselves from the stigma of being labeled gay. Finally, the boys pointed out that their parents made it clear to them that if they were gay they would be disowned.11 O’Higgins-Norman’s study in Ireland also showed the influence of labels on attitudes of homosexuality. The study results found that being normal means being heterosexual and being clearly masculine or feminine. The students in the study also described the use of terms such as faggot, queer, gay, or dyke by students to insult each other as pervasive behavior in the school.5

Research evidence shows that attitudes toward homosexuality are also shaped by religious beliefs.1,2,5,10 In Africa, religious beliefs play a significant role in shaping attitudes toward homosexuality.1 In South Africa, a study examining how teachers position themselves on teaching sexuality education in general and homosexuality in particular in their classrooms found that teachers had prejudices toward homosexuality and the prejudices most commonly arose from their own religious beliefs. In addition, the study results showed that due to the influence of the church, the teachers felt that none of the school administrators would support them in teaching about homosexuality.2 Furthermore, a study in Ireland concluded that due to the Catholic church’s large role in schools in Ireland, the teachers’ negative attitudes toward homosexuality, morals, and behaviors were influenced by religion.5 In Kenya, >90% of the population is religious, with the majority being Christians14; therefore, we expect religion to play a role in students’ perceptions of homosexuality.

Gender differences in perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs about homosexuality

There is vast research evidence indicating a gender difference in attitudes about homosexuality with females generally portraying more positive attitudes than males.5,12,15–20 In their study conducted in Australia, Verweij et al sought to determine the contribution of both genes and shared environment to individual differences in attitudes towards homosexuality using a sample of 4,688 individuals of age ranging from 19 years to 52 years. The results showed that males had significantly more negative attitudes toward homosexuality compared to females.6 Another study by O’Higgins-Norman5 exploring homosexuality and homophobia in secondary schools in Ireland using 15- to –17-year-old high school students found that there was less fear and greater acceptance of gay boys by female students than of lesbians by male students.

Gender differences were also found in a study conducted in Britain by Brewer.15 The purpose of that study was to investigate responses to heterosexual and sexual minority scenarios and the potential influences on attitudes toward homosexuality. The participants included 17- to –26-year-old university students. The study results showed that female students were more accepting of homosexuality than male students. In addition, males with the most negative attitudes toward homosexuality reported the greatest distress in response to nonheterosexual infidelity. Another study conducted in the US examined the relationship between intergroup contact and adolescents’ attitudes regarding homosexuality and the treatment of lesbian and gay peers. Using a sample of 1,069 high school students, the study results showed that females were significantly more likely to rate homosexuality as more acceptable. Also, female respondents reported higher levels of comfort around lesbian and gay peers than males.12

Perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs about homosexuality in African countries

Attitudes toward homosexuality tend to be highly negative in the African culture. Openly gay males in Africa face strong social, cultural, and legal discrimination. Generally, these men are treated as social outcasts and their sexuality is condemned among their families, schools, and religious organizations.4 In most sub-Saharan countries, it is still believed that people are born heterosexual and that sexual minorities are social deviants who should be prosecuted.2 Homophobia is frequently used to describe negative attitudes toward gay men and lesbians. Most African nations define homosexuality as “acts against the order of nature, violations of morality, a scandalous act, indecent act, unnatural offense, indecent practice, gross indecency, and lewd acts.”21 This definition tends to mirror people’s perceptions and attitudes of homosexuality.

Of the 49 African nations reviewed for this study, 40 criminalize homosexuality, with criminal penalties ranging from 3 years to 14 years in prison and/or a fine. Some nations have a penalty of life in prison (Sierra Leone, Sudan, Tanzania, Tunisia, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe), while others have a death penalty (Mauritania, Nigeria, and Sudan). Under Sudan’s Penal Code of 1991, those who engage in homosexuality are punished with flogging by 100 lashes and a 5-year imprisonment.21 Uganda has recently increased the severity of their laws, including jail term for advocacy groups and for actual and intended same-sex practice, which is part of a broader antigay trend in Africa.21 According to Amnesty International,22 homosexuality is illegal in most African countries and is punishable by death in three countries. Even in South Africa, where homosexuality is legal and same-sex marriages are recognized, there is violence against sexual minorities.23,24 Desmond Tutu recently spoke out to end the stigma of homosexuality. He said that antihomosexuality laws in the future would be seen as “wrong” as apartheid laws24 and announced that he does not worship a homophobic God.23,24

A study conducted by Francis2 in Durban, South Africa, sought to grasp an understanding on how life orientation teachers position themselves on the teaching of sexuality education, generally, and homosexuality, specifically, in their classrooms. Life orientation is the study of the self in relation to others and to society. It applies a holistic approach to the personal, social, intellectual, emotional, spiritual, motor, and physical growth and development of learners. The results revealed that none of the teachers indicated that they formally included issues related to homosexuality in teaching sexuality education. Classroom observations revealed little engagement with issues of sexual diversity and homosexuality due to the teachers’ limited knowledge on homosexuality. In addition, the teachers held strong negative attitudes and prejudices toward homosexuality because of their own religious beliefs. The teachers viewed sexual orientation as a choice, and homosexuality as immoral or a passing phase that can be cured.2

In Kenya, homosexuality is illegal and attracts a fine or jail term of 7–14 years for those convicted of practicing it.21 The Kenyan law, sections 162–165 of the Penal Code, criminalizes both actual and attempted same-sex behavior between men, which is referred to as carnal knowledge against the order of nature.25 The new constitution of Kenya, which was ratified in 2010, does not mention homosexuality, but it bans same-sex marriages.26 It is worth noting that the Kenyan Penal Code does not specifically mention lesbian relationships. Kretz27 has identified stages of LGBT legal protection to categorize nations. Currently, Kenya is said to be in the second stage of seven: criminalization of status and behavior. The first stage, total marginalization, even criminalizes advocacy on behalf of LGBT persons, eg, Uganda. The second stage bans open identification or activity of homosexuality.26 “Vilification and social marginalization of LGBT people is commonplace across the African continent, even in nations that have decriminalized homosexuality and instituted anti-discrimination measures.”27

In an answer to the Pew Research28 question “should society accept homosexuality”, 90% of Kenyans said “no” compared to 9% who said “yes”. In South Africa, the respective ratios were 61% and 32%. In Uganda, Ghana, and Senegal, the ratio who answered “no” was 96%, and in Nigeria, it was 98%.29 In the answer to another Pew Research question, “Do you personally believe that homosexuality is morally acceptable, morally unacceptable, or is it not a moral issue?”, 88% of Kenyans viewed it as unacceptable, 3% viewed it as acceptable, and 9% viewed it as not a moral issue.29 Although homosexuality is prohibited by law in Kenya, it still exists as demonstrated in the World Social Forum of 2007 that took place in Nairobi where gay men and lesbians came out to demand their rights.14 From these studies, it is evident there are strong negative attitudes and beliefs about homosexuality in Africa and in Kenya specifically. Surrounded by antihomosexual laws and prejudicial social beliefs, this study sought to examine high school students’ perceptions of homosexuality in Kenya. The majority of high school students attend same-sex boarding schools where they are likely to observe romantic same-sex relationships, if they do exist.

Participants

One thousand two hundred and fifty adolescents (female, n=664; male, n=586) attending three different schools participated in the study. The participants comprised 484 students from an all girls boarding, 339 students from an all boys boarding, and 427 students from a coed day school in the Rift Valley area in Kenya. This is representative of Kenyan high schools where the majority are in single-sex boarding schools. The sample consisted of 26 ninth graders, 327 tenth graders, 721 eleventh graders, and 176 12th graders. Their ages ranged from 13 years to 19 years (mean age =15.26 years). Compared to the coed day school, the two single-sex boarding schools are nationally ranked and draw students from all over the country.30

Procedures

Only those students who had parental consent and who provided individual written assent participated in the study. Parental consent was secured using parental notification letters. Student assent was determined at the time of the survey distribution. The participants completed a questionnaire either in their classroom or in the cafeteria during break time. The questionnaire took ~15–20 minutes to complete. The study was approved by the Ball State University ethics Review Board (IRB) project number 675969.

Measure

Perceptions of homosexuality questionnaire is a 13-item survey developed by Kodero et al31 to assess students’ understanding, attitudes, and beliefs regarding homosexuality. The questions were based on the literature review on homosexuality in Africa. The original survey was qualitative in nature where a representative sample of 546 high school students (225 – all girls boarding, 210 – all boys boarding, and 111 – coed day school) responded to 13 open-ended questions on homosexuality. Their responses were coded and subsequently used to design a quantitative questionnaire. Their responses to each open-ended question became the response options to each quantitative question. The modified questionnaire was then piloted with a different representative sample of 400 students and established a reliability of 0.88.31 The modified version was the one used in the current study. Since the participants included were ninth to 12th grade students with age ranging from 13 years to 19 years, we decided to start by soliciting their definition/descriptions of homosexuality using an open-ended question. To measure students’ understanding of homosexuality practice in their school, they responded to two questions pertaining to the practice of homosexuality: “Do you believe that homosexuality is practiced in your school?” (responses were yes, no, not sure) and “In which type of school do you believe homosexuality is practiced?” (responses were all types of schools, boys boarding schools, girls boarding schools, coed boarding schools, boys day schools, girls day schools, coed day schools, none of the schools). To measure students’ attitudes and beliefs regarding homosexuality, they were asked: “What do you believe is the cause of homosexuality?” (responses were biological/genes inherited from parents, socialization process, sexual starvation, demons/Satan, Western cultural influence, other [please specify]) and “What is your belief about gay/lesbian practice?” (responses were it is a normal sexual behavior, do not know, it is an abnormal sexual behavior). To assess students’ beliefs about the nature of one’s sexual orientation, they were asked the following questions whose responses were yes, no, or not sure: “Do you believe those students who engage in gay/lesbian relationship will change to heterosexual relationship after they graduate from high school?”, “Do you believe counseling can make students who are involved in gay/lesbian practice change their sexual orientation?”, and “Do you believe prayers can make students who are involved in gay/lesbian practice change their sexual orientation?”. We also asked questions to participants on what they thought should be done to students caught engaging in gay/lesbian relationships at school: “Do you think students caught engaging in gay/lesbian practice should be punished by the school administration?”, “Do you think students caught engaging in gay/lesbian practice should be suspended from school?”, and “Do you think students caught engaging in gay/lesbian practice should be expelled from school?” The responses to these three questions were similar to the previous one (yes, no, not sure). Finally, the participants were asked about teachers’ and parents’ awareness of their students’/children’s practice of homosexuality at school: “Do you believe that teachers in your school are aware that some students are engaged in gay/lesbian relationships?” and “Do you believe that parents/guardians are aware that their child is engaged in a gay/lesbian relationship in your school?” (the responses were yes, no, not sure). This questionnaire has been used previously and received test–retest reliabilities of 0.88 and 0.89.31

Results

Definition/description of homosexuality

To start, we solicited participants’ definitions/descriptions of homosexuality using an open-ended question. According to their responses, homosexuality is a sexual relationship between two people of the same gender (80%), having sex with a person of the same gender (13%), when a boy has sex with another boy (6%), having sex with only men (0.6%), and when you have no sex (0.4%). Note that only one/first response was included in the analysis.

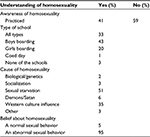

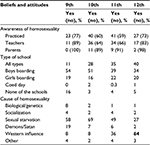

Awareness of same-sex contacts

To examine participants’ awareness of homosexuality within their school, we conducted descriptive statistics to get the frequency of their responses. As previously stated, due to the age of some of the participants (13 years), we included a question on the meaning of homosexuality. The results showed that almost all of the participants (97%) knew the meaning of homosexuality and 40% claimed that homosexuality is practiced in high schools in Kenya. When asked in which type of school they believe homosexuality is most practiced, 61% answered single-sex boarding high schools (41% answered boys’ and 21% answered girls’ boarding schools; Table 1). To examine gender, grade, and school differences in participants’ awareness of homosexuality, we conducted chi-square analyses. The results revealed a significant gender difference on the practice of homosexuality in school, χ2 (1)=9.21, P=0.003, with more females (43%) reporting the practice in their school compared to males (34%), and on the type of school where homosexuality is most practiced, χ2 (7)=147.02, P=0.000, with 44% of females reporting all types of schools and 55% of males reporting all boys’ boarding schools (Table 2). The analyses also revealed significant grade differences. The ninth and 12th graders reported less evidence of gay/lesbian practice in their school (23% and 27%, respectively) compared to the tenth and eleventh graders (40% and 41%; Table 3). This difference was significant, χ2 (3)=14.52, P=0.002. Significant school differences were also found, χ2 (14)=150.21, P=0.000, with 54% of the males reporting that homosexuality is mostly practiced in the all boys’ boarding school (Table 4).

| Table 1 Understanding, beliefs, and attitudes about homosexuality |

| Table 2 Sexual orientation and change |

| Table 3 Beliefs and attitudes about homosexuality by gender |

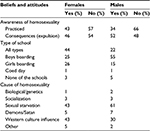

Beliefs and attitudes about homosexuality

More descriptive statistics were conducted to examine students’ beliefs and attitudes toward homosexuality. The results revealed that overall 52% of the participants believed sexual starvation to be the main cause of homosexuality. In addition, the results indicated that 95% of the participants believed that homosexuality is an abnormal sexual behavior, 60% believed that students who engage in homosexuality will not change to heterosexuality after school, and 64% believed that prayers and 86% believed that counseling can change students’ sexual orientation (Table 1). Chi-square tests of analyses were conducted to examine whether there were gender, grade, and school differences in participants’ beliefs and attitudes about homosexuality. There were significant gender differences on the cause of homosexuality, χ2 (5)=55.72, P=0.000, with more males (61%) than females (43%) reporting sexual starvation as the main cause of homosexuality (Table 4). There were also significant grade differences, χ2 (15)=142.68, P=0.000, with more 12th graders reporting Western influence as the main cause of homosexuality (64%; Tables 5 and 6). However, school differences showed the girls’ boarding school reported Western cultural influence (49%) as the main cause of homosexuality, while the boys’ boarding (63%) and the coed school (56%) reported sexual starvation as the main cause of homosexuality, χ2 (10)=90.11, P=0.000. In addition, more participants from the coed day school (69%) reported that those engaging in gay/lesbian relationships at school will not change after leaving school, χ2 (2)=26.62, P=0.000 (Tables 7 and 8).

| Table 4 Beliefs and attitudes about homosexuality between gender Note: Females, n=664; males, n=586. Abbreviation: df, degrees of freedom. |

| Table 5 Beliefs and attitudes about homosexuality by grade level Note: Data in bold indicates a significant difference between grade levels. |

| Table 6 Beliefs and attitudes about homosexuality across grade levels Note: ninth, n=26; tenth, n=327; eleventh, n=721; 12th, n=176. Abbreviation: df, degrees of freedom. |

| Table 7 Beliefs and attitudes about homosexuality by school |

| Table 8 Beliefs and attitudes about homosexuality across schools Note: Females, n=664; males, n=586. Abbreviation: df, degrees of freedom. |

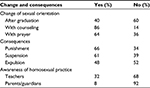

Consequences of practicing homosexuality

Descriptive statistics and chi-square tests of analyses were conducted to examine participants’ views on what should happen to students who engage in gay/lesbian relationships at school. In all, 66% said that they should be punished, 61% reported that they should be suspended from school, and 49% said that they should be expelled from school. Significant gender differences were found on whether students should be expelled from school, χ2 (1)=4.13, P=0.042, with more males (52%) endorsing expulsion from school compared to females (46%; Tables 5 and 6). There were also significant school differences, χ2 (2)=12.62, P=0.002, with fewer students (42%) from the coed day school endorsing expulsion from school (Tables 7 and 8).

Teachers’ and parents’/guardians’ awareness of homosexuality at school

To examine participants’ views on teachers’ and parents’/guardians’ knowledge about homosexuality practice at school, we conducted descriptive and chi-square tests of analyses. The results of descriptive statistics showed that 68% of teachers and 92% of parents/guardians were not aware of gay/lesbian relationships at school. There were significant grade differences, χ2 (3)=26.51, P=0.000, with more ninth (89%) and 12th graders (82%) reporting that teachers are not aware of gay/lesbian relationships at school. In addition, a majority of 12th graders (98%) believed that parents/guardians are not aware of their children’s gay/lesbian relationships at school, χ2 (3)=17.24, P=0.000 (Tables 5 and 6). School differences were also found on teachers’ awareness, χ2 (2)=17.16, P=0.000, with more coed day scholars stating that their teachers were less aware of the practice (74%), while the girls’ boarding school thought that parents/guardians were the ones who were less aware (96%) of this practice at school, χ2 (2)=15.80, P=0.000 (Tables 7 and 8). There were no significant gender differences on perceptions of teachers and parental awareness.

Discussion and conclusion

From these findings, it is apparent that students perceive that homosexuality exists in schools in Kenya, but these students are ill informed about homosexuality. The students in the current study believed that homosexuality is mostly practiced in single-sex boarding schools, specifically boys’ boarding schools. Consequently, they believed that homosexuality is caused by sexual starvation. However, when asked whether these students will change their sexual orientation after they graduate from high school, the majority responded by saying no. On the contrary, these students believed that prayers and counseling can change one’s sexual orientation. Furthermore, almost all the students believed that homosexuality is an abnormal sexual behavior. The results of this study support and extend the research on perceptions of homosexuality. These results indicate that students are less informed about homosexuality and suggest that negative attitudes and beliefs about homosexuality exist and are strong.1,2,5,6,9,11,13,15,32

The majority of participants endorsed punishment and suspension of those students found engaging in gay/lesbian relationships. However, a few recommended expulsion from school as a consequence of engaging in homosexuality. This could be attributed to the student affiliation that develops when students are together for 10 months out of the year, especially those in boarding schools. Second, while we found evidence of gender and grade-level differences in students’ understanding of the cause of homosexuality and the consequences of engaging in same-sex relationships at school, this study found little evidence of gender, grade level, and school differences in students’ attitudes and beliefs on whether homosexuality is a normal behavior, whether students will change their sexual orientation, and the role of prayers and counseling in homosexuality, suggesting that negative attitudes and beliefs about homosexuality may be related more to the cultural context than gender and developmental differences.2,3 Similar to previous research, this study found that students believed that teachers and parents/guardians were not aware of homosexuality practice at school.1,2,5 It is possible that few teachers/parents talk to their students/children about homosexuality; hence, students assume that teachers/parents are not aware of homosexuality practice at school.

Gender differences

Interestingly, more females than males reported that homosexuality is practiced in their schools. Furthermore, females believed that homosexuality is practiced in all types of schools contrary to males who reported that homosexuality is predominantly practiced in the all boys’ boarding schools. We speculate that this finding is influenced by social stereotypes about homosexuality, which tend to portray more negative attitudes toward gay men than toward lesbians.1,5,6 Also, more males were likely to endorse school expulsion as a consequence for engaging in gay/lesbian relations. The fact that females were less likely to recommend a harsher punishment is supported by research that shows that females are more accepting of homosexuality than males.5,6,11,12,15,20

Grade-level differences

Contrary to the study of Verweij et al6 that found no age differences, the current study found grade/age differences in students’ understanding, attitudes, and beliefs about homosexuality. Given the big age difference (13–19 years) with the younger students belonging to the lower grades, we expected these differences. However, the direction of some of the differences was surprising. For example, we expected the juniors and seniors (eleventh and 12th graders) to have a better understanding of homosexuality compared to the freshmen and sophomores. Interestingly, fewer freshmen and seniors believed that homosexuality was practiced at their school. Furthermore, all freshmen and almost all seniors (98%) believed that parents/guardians were not aware of the practice of homosexuality at school. We have no possible explanation for this finding. Future studies should include a qualitative approach to help interpret this outcome. Also, even though freshmen, sophomores, and juniors believed that homosexuality was caused by sexual starvation, the majority of the seniors believed that Western cultural influences were the main cause of homosexuality. Once more, having a mixed-method design involving qualitative and quantitative methods would aid in understanding the meaning of respondents’ interpretations of the questions and what they meant to communicate through their responses.

School differences

The findings of this study suggest that more students from the all girls’ boarding school are aware of the practice of homosexuality at their school compared to those from the all boys’ boarding and coed day schools. It could be that students in the all girls’ boarding school feel comfortable talking about homosexuality or it could be that there are fewer negative stereotypes about lesbians compared to gay men.1,5,11,15 In addition, as previously mentioned, the Kenyan law and constitution specifically mentions gay men, not lesbians.26 Interestingly, students from the all boys’ boarding school indicated that homosexuality is practiced mostly in the all boys’ boarding schools, while students from the all girls’ boarding school reported that homosexuality is practiced in all types of high schools. Also, while students from the all boys’ boarding and coed day schools believed sexual starvation caused homosexuality, students from the all girls’ boarding school reported Western cultural influence to be the main cause of homosexuality. These findings reveal a lack of understanding of homosexuality among Kenyan high school students. The implication of this finding calls for a mixed-method design to capture a nuanced understanding of students’ responses to the quantitative questions.

It made sense that few students in the coed day school believed that those practicing homosexuality will change after they graduate from high school, since they interact with the opposite sex peers on a regular basis and those interested in heterosexual relationships have the opportunity to do so. When asked what should be done to students caught engaging in gay/lesbian relationships at school, students from the coed day school were more forgiving. Compared to the single-sex boarding schools, the coed day school students were less likely to recommend punishment, suspension, or expulsion from school. As a matter of fact, over half of the students from the all boys’ boarding school endorsed expulsion from school for those who engage in homosexuality. This is contrary to the school and classroom climate research that suggest that students who are in close contact with each other on a regular basis (10 months out of 12 months of the year), such as those in the same-sex boarding schools, are more likely to form close ties with each other. These students develop strong affiliations with each other and establish new “families” away from home.33–36 Therefore, it would suffice to predict that students in boarding schools will be less likely to recommend harsh punishment, such as expulsion from school. However, as mentioned previously, homosexuality in boys’ boarding schools is a serious issue that poses harm to some of the boys due to the lack of distinction between sexual abuse and homosexuality.14 This calls for dialogue on this controversial topic. Given that students perceive homosexuality to exist in their schools, there is a need for the teachers to openly talk about this topic so that students have an informed understanding of homosexuality. In addition, since students believe homosexuality is an abnormal sexual behavior, they may tolerate bullying of students suspected of being gay. Finally, students from the coed day school thought that teachers were not aware of homosexuality practice, while students from the all girls’ boarding school believed that parents/guardians were not aware of their children’s homosexuality. More research is needed to extrapolate the implication of this finding.

It is evident that students have contradictory attitudes and beliefs about homosexuality. They appear to be ill informed about the nature of homosexuality. Adolescents spend a significant amount of time in school providing school environments that are open and conducive to conversations of identity development, including sexual identity that would be helpful in addressing some of these ill-informed views. There were fewer evidences of gender and grade-level differences in students’ understanding, attitudes, and beliefs about homosexuality. However, there were several school differences suggesting that attitudes and beliefs about homosexuality are influenced more by the social context and less by gender and developmental differences. This social context influence is supported by previous research that shows strong negative attitudes and beliefs about homosexuality in Africa.1,2,21,22,25–27,29 When the government has stipulated laws against homosexuality, including 7–14 years of imprisonment, in addition to the strong antihomosexuality religious beliefs, it is no wonder that the social context of school had more impact on students’ attitudes and beliefs about homosexuality. It is also important to point out that counseling is a relatively new field of study in Kenya; therefore, students may not fully understand its impact and role in human development. There is a need for future research to qualitatively examine students’ understanding of the field of counseling. It is encouraging that some schools are allowing researchers to conduct studies on this sensitive and controversial topic. The importance of more research on this topic cannot be overlooked.

This study had some limitations. Owing to the nature of the study, there were no open-ended questions on the survey, which makes it impossible to fully interpret students’ responses, especially their conflicting attitudes and beliefs about homosexuality. Also, due to the cultural context of the study, there was no information on students’ sexual orientation. Having this information would have strengthened our understanding of students’ responses on most of the questions. It is important to note that the researchers of the present study were not allowed to collect any qualitative data from the students due to the nature of the topic. Hopefully, in future, this will be possible. In conclusion, this study provides insights into the complexity of the topic of homosexuality and the challenges of studying it. The important information to gain is that slowly, but surely, the conversation, however limited in scope, is taking place.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Chadee D, Brewster D, Subhan S, et al. Persuasion and attitudes towards male homosexuality in a University Caribbean sample. J East Caribb Stud. 2012;37(1):1–21. | ||

Francis DA. Teacher positioning on the teaching of sexual diversity in South African schools. Cult Health Sex. 2012;14(6):597–611. | ||

Mustanski B, Birkett M, Greene GJ, Rosario M, Bostwick W, Everett BG. The association between sexual orientation identity and behavior across race/ethnicity, sex, and age in a probability sample of high school students. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(2):237–244. | ||

Mwaba K. Attitudes and beliefs about homosexuality and same sex marriage among a sample of South African students. Soc Behav Personal. 2009;37(6):801–804. | ||

O’Higgins-Norman J. Straight talking: explorations on homosexuality and homophobia in secondary schools in Ireland. Sex Educ. 2009;9(4):381–393. | ||

Verweij KH, Shekar SN, Zietsch BP, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on individual differences in attitudes toward homosexuality: an Australian twin study. Behav Genet. 2008;38(3):257–265. | ||

Savin-Williams RC. Girl-on-girl sexuality. In: Leadbetter BJR, Way N, editors. Urban Girls Revisited: Building Strengths. New York, NY: New York University Press; 2007:301–318. | ||

Savin-Williams RC, Cohen KM. Development of same-sex attracted youth. In: Meyer H, Northridge ME, editors. The Health of Sexual Minorities. New York, NY: Springer; 2007:27–47. | ||

Pérez-Testor C, Behar J, Davins M, et al. Teachers’ attitudes and beliefs about homosexuality. Span J Psychol. 2010;13(1):138–155. | ||

Bowland SE, Foster K, Vosler AR. Culturally competent and spiritually sensitive therapy with lesbian and gay Christians. Soc Work. 2003;58(4):321–332. | ||

Mora R. “Dicks are for chicks”: Latino boys, masculinity, and the abjection of homosexuality. Gender Educ. 2013;25(3):340–356. | ||

Heinze JE, Horn SS. Intergroup contact and beliefs about homosexuality in adolescence. J Youth Adolesc. 2009;38(7):937–951. | ||

Gowen LK, Winges-Yanez N. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning youths’ perspectives of inclusive school-based sexuality education. J Sex Res. 2014;51(7):788–800. | ||

Barasa L. Kenyan gays and lesbians step out to demand rights. Daily Nation. 2007 Jan 26; p.3. | ||

Brewer G. Heterosexual and homosexual infidelity: the importance of attitudes towards homosexuality. Pers Indiv Differ. 2014;64(1):98–100. | ||

Cao H, Wang P, Gao Y. A survey of Chinese university students’ perceptions of and attitudes towards homosexuality. Soc Behav Personal. 2010;38(6):721–728. | ||

Chesir-Teran D, Hughes D. Heterosexism in high school and victimization among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and questioning students. J Youth Adolesc. 2009;38(1):963–975. | ||

Horn SS, Szalacha LA, Drill K. Schooling, sexuality, and rights: an investigation of heterosexual students’ social cognition regarding sexual orientation and the rights of gay and lesbian peers in school. J Soc Issues. 2008;64(4):791–813. | ||

Rogers A, McRee N, Arntz DL. Using a college human sexuality course to combat homophobia. Sex Educ. 2009;9(3):211–225. | ||

Wright PJ, Bae S. Pornography consumption and attitudes toward homosexuality: a national longitudinal study. Hum Commun Res. 2013;39(4):492–513. | ||

The Law Library of Congress. Laws on Homosexuality in African Nations. Washington, DC: Global Legal Research Center; 2014. | ||

Amnesty International, UK [webpage on the Internet]. Mapping anti-gay laws in Africa; 2015 [about 2 p]. Available from: http://www.amnesty.org.uk/lgbti-lgbt-gay-human-rights-law-africa-uganda-kenya-nigeria-cameroon#.U4x_YfldWS8. Accessed July 25, 2015. | ||

BBC News [webpage on the Internet]. Tutu calls for end to gay stigma to help tackle HIV; 2012 [about 2 p]. Available from: http://www.bbc.com/news/health-18913497. Accessed July 20, 2012. | ||

BBC News [webpage on the Internet]. Archbishop Tutu “would not worship a homophobic God”; 2013 [about 2 p]. Available from: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-23464694. Accessed July 27, 2013. | ||

The Republic of Kenya. Laws of Kenya: The Penal Code. Nairobi: Government Printers; 2009. [Rev ed.]. | ||

The Republic of Kenya. The Constitution of Kenya. Nairobi: Government Printers; 2010. | ||

Kretz AJ. From “Kill the gays” to “Kill the gay rights movement”: the future of homosexuality legislation in Africa. J Int Human Rights. 2013;11(2):207–244. | ||

Pew Research [webpage on the Internet]. The global divide on homosexuality. Global Attitudes Project; 2013 [about 3 p]. Available from: http://www.pewglobal.org/2013/06/04/the-global-divide-on-homosexuality/. Accessed July 5, 2015. | ||

Pew Research [webpage on the Internet]. Global views on morality: homosexuality. Global Attitudes Project; 2014 [about 3 p]. Available from: http://www.pewglobal.org/2014/04/15/global-morality/table/homosexuality/. Accessed July 5, 2015. | ||

Kenya Institute of Education. Creating Acceptable Educational Standards. Nairobi: Kenya Institute of Education; 2014. | ||

Kodero HM, Misigo BL, Owino EA, Mucherah W. Perceptions of students on homosexuality in secondary schools in Kenya. Int J Curr Res. 2011;3(7):279–284. | ||

Borsel J, Putte A. Lisping and male homosexuality. Arch Sex Behav. 2004;43(6):1159–1163. | ||

Fraser BJ. Research on classroom and school climate. In: Gabel DL, editor. Handbook of Research on Science Teaching and Learning. New York, NY: Macmillan; 1994:493–541. | ||

Mucherah W. Classroom climate and students’ goal structures in high school biology classrooms in Kenya. Learn Environ Res. 2008;11:63–81. | ||

Trickett EJ, Moos RH. A Social Climate Scale: Classroom Environment Scale Manual. 3rd ed. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologist Press; 1995. | ||

Walberg HJ, editor. Educational Environments and Effects: Evaluation, Policy, and Productivity. Berkley, CA: McCutchan; 1979. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.